Intensity Paradox—Low-Fit People Are Physically Most Active in Terms of Their Fitness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

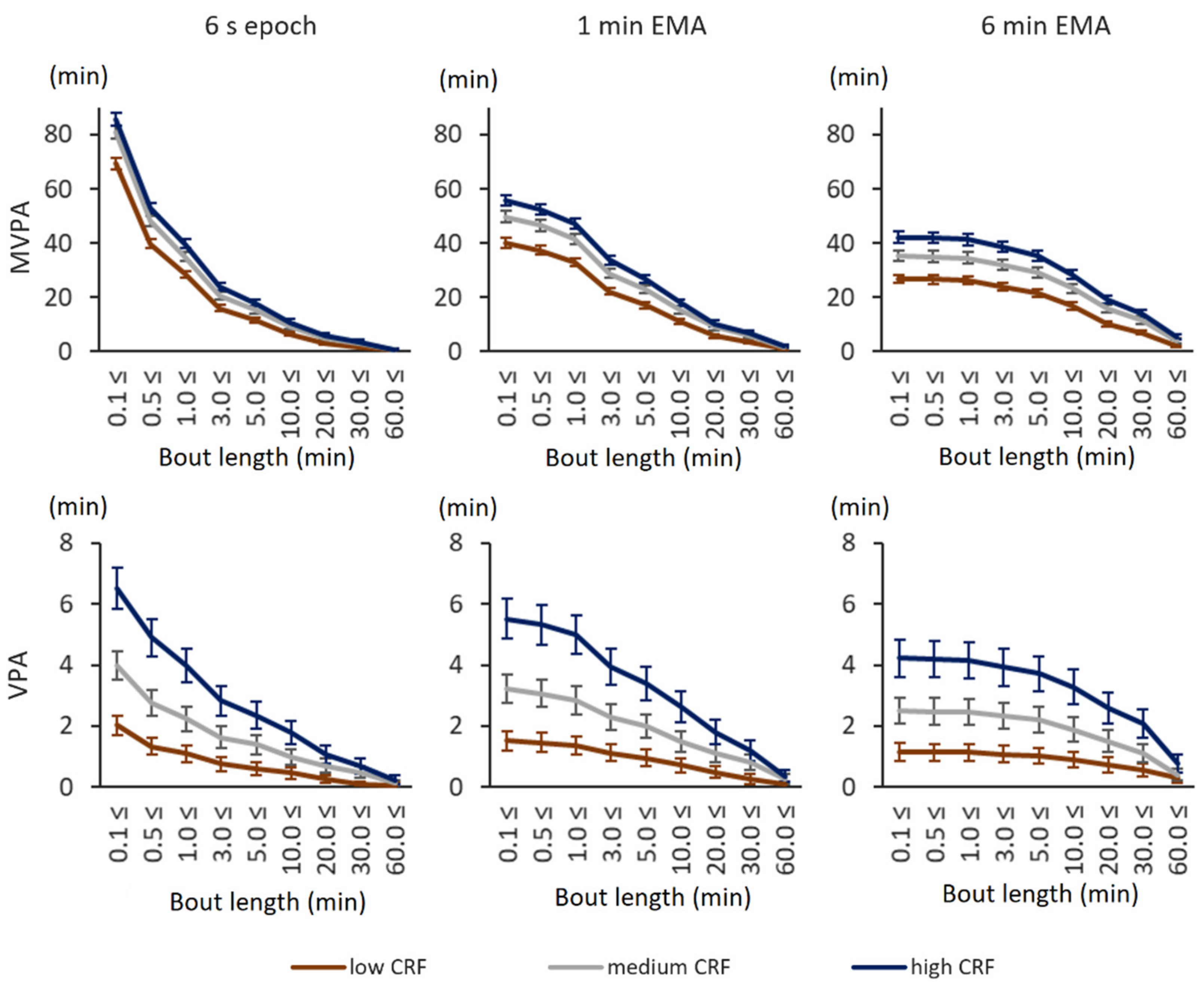

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Green, H.J.; Macdonald, M.J.; Hughson, R.L. Progressive effect of endurance training on VO2 kinetics at the onset of submaximal exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995, 79, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguera, B.; Proctor, D.; Dietz, N.; Guo, Z.; Joyner, M.; Jensen, M.D. Leg free fatty acid kinetics during exercise in men and women. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 278, E113–E117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, P.; Di Loreto, C.; Lucidi, P.; Murdolo, G.; Parlanti, N.; De Cicco, A.; Santeusanio, F.P.F. Metabolic response to exercise. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2003, 26, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijn, J.A.; Coyle, E.F.; Sidossis, L.S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Horowitz, J.F.; Endert, E.; Wolfe, R.R. Regulation of endogenous fat and carbohydrate metabolism in relation to exercise intensity and duration. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 1993, 265, E380–E391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banda, J.A.; Haydel, K.F.; Davila, T.; Desai, M.; Bryson, S.; Haskell, W.L.; Matheson, D.; Robinson, T.N. Effects of Varying Epoch Lengths, Wear Time Algorithms, and Activity Cut-Points on Estimates of Child Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity from Accelerometer Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauman, A. Updating the evidence that physical activity is good for health: An epidemiological review 2000–2003. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2004, 7, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haskell, W.L.; Lee, I.M.; Pate, R.R.; Powell, K.E.; Blair, S.N.; Franklin, B.A.; Macera, C.A.; Heath, G.W.; Thompson, P.D.; Bauman, A. Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekelund, U.; Dalene, K.E.; Tarp, J.; Lee, I.-M. Physical activity and mortality: What is the dose response and how big is the effect? Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1125–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, J.; Aaby, D.; Montag, S.E.; Sidney, S.; Sternfeld, B.; Welch, W.A.; Carnethon, M.R.; Liu, K.; Craft, L.L.; Gabriel, K.P.; et al. Individualized Relative Intensity Physical Activity Accelerometer Cut-points. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M.D.A.; Da Silva, I.; Ramires, V.; Reichert, F.; Martins, R.; Ferreira, R.; Tomasi, E. Metabolic equivalent of task (METs) thresholds as an indicator of physical activity intensity. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Miller, N.E.; Strath, S.J.; Swartz, A.M.; Cashin, S.E. Estimating absolute and relative physical activity in-tensity across age via accelerometry in adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2010, 18, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zisko, N.; Carlsen, T.; Øyvind, S.; Aspvik, N.P.; Ingebrigtsen, J.E.; Wisløff, U.; Stensvold, D. New relative intensity ambulatory accelerometer thresholds for elderly men and women: The Generation 100 study. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bittner, V.; Weiner, D.H.; Yusuf, S.; Rogers, W.J.; Mcintyre, K.M.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Greenberg, B. Prediction of mortality and morbidity with a 6-minute walk test in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. JAMA 1993, 270, 1702–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, J.F.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Faktor, M.D.; Warburton, D.E.R. The 6-Minute Walk Test as a Predictor of Objectively Measured Aerobic Fitness in Healthy Working-Aged Adults. Physician Sportsmed. 2011, 39, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostagno, C.; Gensini, G.F. Six minute walk test: A simple and useful test to evaluate functional capacity in patients with heart failure. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2008, 3, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mänttäri, A.; Suni, J.; Sievänen, H.; Husu, P.; Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Valkeinen, H.; Tokola, K.; Vasankari, T. Six-minute walk test: A tool for predicting maximal aerobic power (VO2max) in healthy adults. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2018, 38, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husu, P.; Tokola, K.; Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Sievänen, H.; Suni, J.; Heinonen, O.; Heiskanen, J.; Kaikkonen, K.; Savonen, K.; Kokko, S.; et al. Physical activity, sedentary behavior and time in bed among Finnish adults measured 24/7 by triaxial accelerometry. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Caramaliu, R.V.; Vasile, A.; Bacis, I. Wearable vital parameters monitoring system. In Advanced Topics in Optoelectronics, Microelectronics, and Nanotechnologies 2014; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 9258, p. 92580R. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeschke, L.; Luzak, A.; Steinbrecher, A.; Jeran, S.; Ferland, M.; Linkohr, B.; Schulz, H.; Pischon, T. 24 h-accelerometry in epidemiological studies: Automated detection of non-wear time in comparison to diary information. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Vasankari, T.; Husu, P.; Suni, J.; Sievänen, H. A universal, accurate intensity-based classification of different physical activities using raw data of accelerometer. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2015, 35, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Vasankari, T.; Husu, P.; Mänttäri, A.; Vuorimaa, T.; Suni, J.; Sievänen, H. Validation of Cut-Points for Evaluating the Intensity of Physical Activity with Accelerometry-Based Mean Amplitude Deviation (MAD). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Husu, P.; Suni, J.; Vasankari, T.; Sievänen, H. Reliable recognition of lying, sitting, and standing with a hip-worn accelerometer. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 28, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kujala, U.; Pietilä, J.; Myllymäki, T.; Mutikainen, S.; Föhr, T.; Korhonen, I.; Helander, E. Physical activity: Absolute intensity vs. relative-to-fitness-level volumes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisko, N.; Nauman, J.; Sandbakk, S.B.; Aspvik, N.P.; Øyvind, S.; Carlsen, T.; Viken, H.; Ingebrigtsen, J.E.; Wisløff, U.; Stensvold, D. Absolute and relative accelerometer thresholds for determining the association between physical activity and metabolic syndrome in the older adults: The Generation-100 study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundby, C.; Robach, P. Performance Enhancement: What Are the Physiological Limits? Physiology 2015, 30, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bacon, A.; Carter, R.; Ogle, E.; Joyner, M. VO2max trainability and high intensity interval training in humans: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgerud, J.; Høydal, K.; Wang, E.; Karlsen, T.; Berg, P.; Bjerkaas, M.; Hoff, J. Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve VO2max more than moderate training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scribbans, T.D.; Vecsey, S.; Hankinson, P.B.; Foster, W.S.; Gurd, B.J. The Effect of Training Intensity on VO2max in Young Healthy Adults: A Meta-Regression and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2016, 9, 230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Saltin, B.; Calbet, J.A. Point: In health and in a normoxic environment, VO2 max is limited primarily by cardiac output and locomotor muscle blood flow. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gledhill, N.; Cox, D.; Jamnik, R. Endurance athletes’ stroke volume does not plateau: Major advantage is diastolic function. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Conlee, R.K.; Jensen, R.; Fellingham, G.W.; George, J.D.; Fisher, A.G. Stroke volume does not plateau during graded exercise in elite male distance runners. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1849–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, P.B. Training for intense exercise performance: High-intensity or high-volume training? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, S. What is Best Practice for Training Intensity and Duration Distribution in Endurance Athletes? Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2010, 5, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.J.; Williams, M.G.; Eynon, N.; Ashton, K.J.; Little, J.P.; Wisloff, U.; Coombes, J.S. Genes to predict VO2max trainability: A systematic review. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, D.; Lundby, C. Refuting the myth of non-response to exercise training: ‘Non-responders’ do respond to higher dose of training. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3377–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, C.; Kiely, J. Do Non-Responders to Exercise Exist—And If So, What Should We Do About Them? Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holtermann, A.; Krause, N.; Van Der Beek, A.J.; Straker, L. The physical activity paradox: Six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. BMJ 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mann, T.N.; Lamberts, R.P.; Lambert, M.I. High responders and low responders: Factors associated with individual variation in response to standardized training. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujika, I. The Cycling Physiology of Miguel Indurain 14 Years after Retirement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2012, 7, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tønnessen, E.; Hisdal, J.; Ronnestad, B.R. Influence of Interval Training Frequency on Time-Trial Performance in Elite Endurance Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C. Monitoring training in athletes with reference to overtraining syndrome. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age Group | N | Low CRF | Middle CRF | High CRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||

| 20–29 | 55 | 18.0–41.6 | 41.6–44.2 | 45.2–53.4 |

| 30–39 | 133 | 27.5–38.2 | 38.2–42.1 | 42.2–53.3 |

| 40–49 | 160 | 19.7–35.3 | 35.5–41.0 | 41.0–50.2 |

| 50–59 | 191 | 15.9–32.7 | 32.8–37.1 | 37.1–46.4 |

| 60–69 | 264 | 11.2–29.1 | 29.2–33.6 | 33.6–43.8 |

| Women | ||||

| 20–29 | 120 | 20.1–35.0 | 35.0–38.6 | 38.7–48.6 |

| 30–39 | 185 | 20.3–33.4 | 33.4–38.1 | 38.1–46.3 |

| 40–49 | 236 | 17.3–32.6 | 32.6–37.2 | 37.2–47.0 |

| 50–59 | 267 | 9.9–28.6 | 28.6–33.7 | 33.8–43.0 |

| 60–69 | 341 | 14.5–27.0 | 27.1–31.6 | 31.6–41.5 |

| Age Group | Low CRF | Middle CRF | High CRF | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Weight | Over-Weight | Obese | Normal Weight | Over-Weight | Obese | Normal Weight | Over-Weight | Obese | |

| Men | |||||||||

| 20–29 | 28% | 61% | 11% | 50% | 39% | 11% | 84% | 16% | 0% |

| 30–39 | 30% | 32% | 39% | 32% | 66% | 2% | 60% | 40% | 0% |

| 40–49 | 9% | 49% | 42% | 32% | 60% | 8% | 69% | 30% | 2% |

| 50–59 | 11% | 45% | 44% | 29% | 63% | 8% | 45% | 48% | 6% |

| 60–69 | 13% | 47% | 41% | 24% | 58% | 18% | 58% | 38% | 5% |

| Women | |||||||||

| 20–29 | 38% | 45% | 18% | 78% | 23% | 0% | 98% | 3% | 0% |

| 30–39 | 24% | 45% | 31% | 72% | 25% | 3% | 92% | 6% | 2% |

| 40–49 | 8% | 38% | 54% | 71% | 29% | 0% | 94% | 6% | 0% |

| 50–59 | 1% | 39% | 60% | 39% | 56% | 4% | 82% | 18% | 0% |

| 60–69 | 9% | 43% | 48% | 36% | 55% | 9% | 77% | 23% | 0% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vähä-Ypyä, H.; Sievänen, H.; Husu, P.; Tokola, K.; Vasankari, T. Intensity Paradox—Low-Fit People Are Physically Most Active in Terms of Their Fitness. Sensors 2021, 21, 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21062063

Vähä-Ypyä H, Sievänen H, Husu P, Tokola K, Vasankari T. Intensity Paradox—Low-Fit People Are Physically Most Active in Terms of Their Fitness. Sensors. 2021; 21(6):2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21062063

Chicago/Turabian StyleVähä-Ypyä, Henri, Harri Sievänen, Pauliina Husu, Kari Tokola, and Tommi Vasankari. 2021. "Intensity Paradox—Low-Fit People Are Physically Most Active in Terms of Their Fitness" Sensors 21, no. 6: 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21062063

APA StyleVähä-Ypyä, H., Sievänen, H., Husu, P., Tokola, K., & Vasankari, T. (2021). Intensity Paradox—Low-Fit People Are Physically Most Active in Terms of Their Fitness. Sensors, 21(6), 2063. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21062063