Familiarization with Mixed Reality for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Eye Tracking Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Participants must be older than ten years of age;

- Participants cannot have a diagnosis of ASD;

- Participants must not exhibit psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity, depression, bipolar disorders, or schizophrenia.

- Participants must not have a neurological history that includes conditions like epilepsy or cerebrovascular accidents;

- Participants must provide their informed consent verbally and in writing after receiving comprehensive information about the study.

- Participants must be older than ten years of age;

- Participants had at least one ASD diagnosis;

- Participants must provide their informed consent verbally and in writing after receiving comprehensive information about the study.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Familiarization with the MR Headset

2.2.2. Familiarization with the Headset

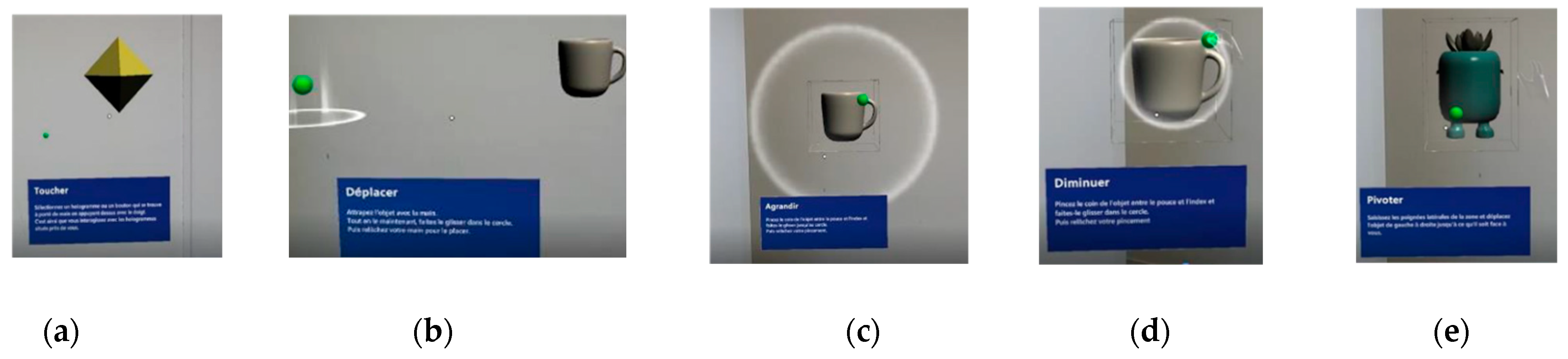

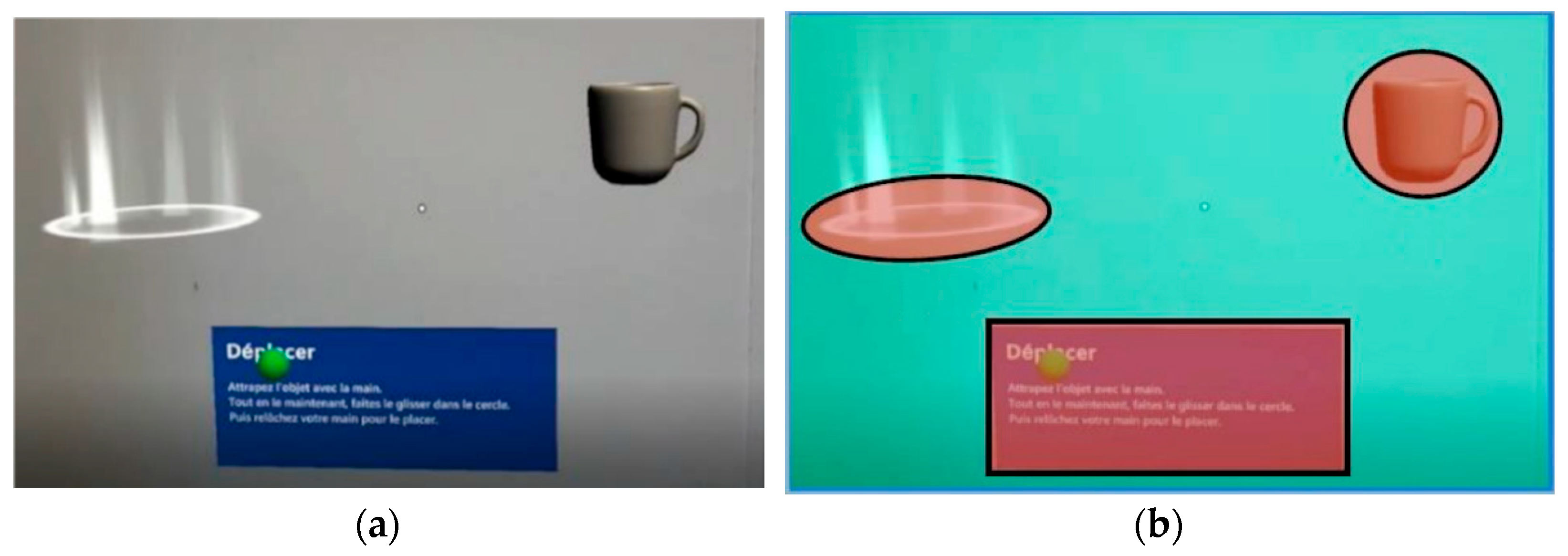

2.2.3. Familiarization with Mixed Reality

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. HoloLens 2

2.3.2. Front Camera

2.3.3. Eye Tracking

- An imputing function for not a number (Nan) values in the raw eye tracking data by using linear interpolation for temporal windows smaller than 75 ms;

- A function that classifies raw data as a fixation if the data within a 250 ms time window do not exceed a distance of 1.6 degrees;

- A function that merges fixations close to 1.6 degrees of distance within a 75 ms time window.

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Study Procedure

2.6. Results Analysis

2.7. Hypotheses and Statistical Treatments

3. Results

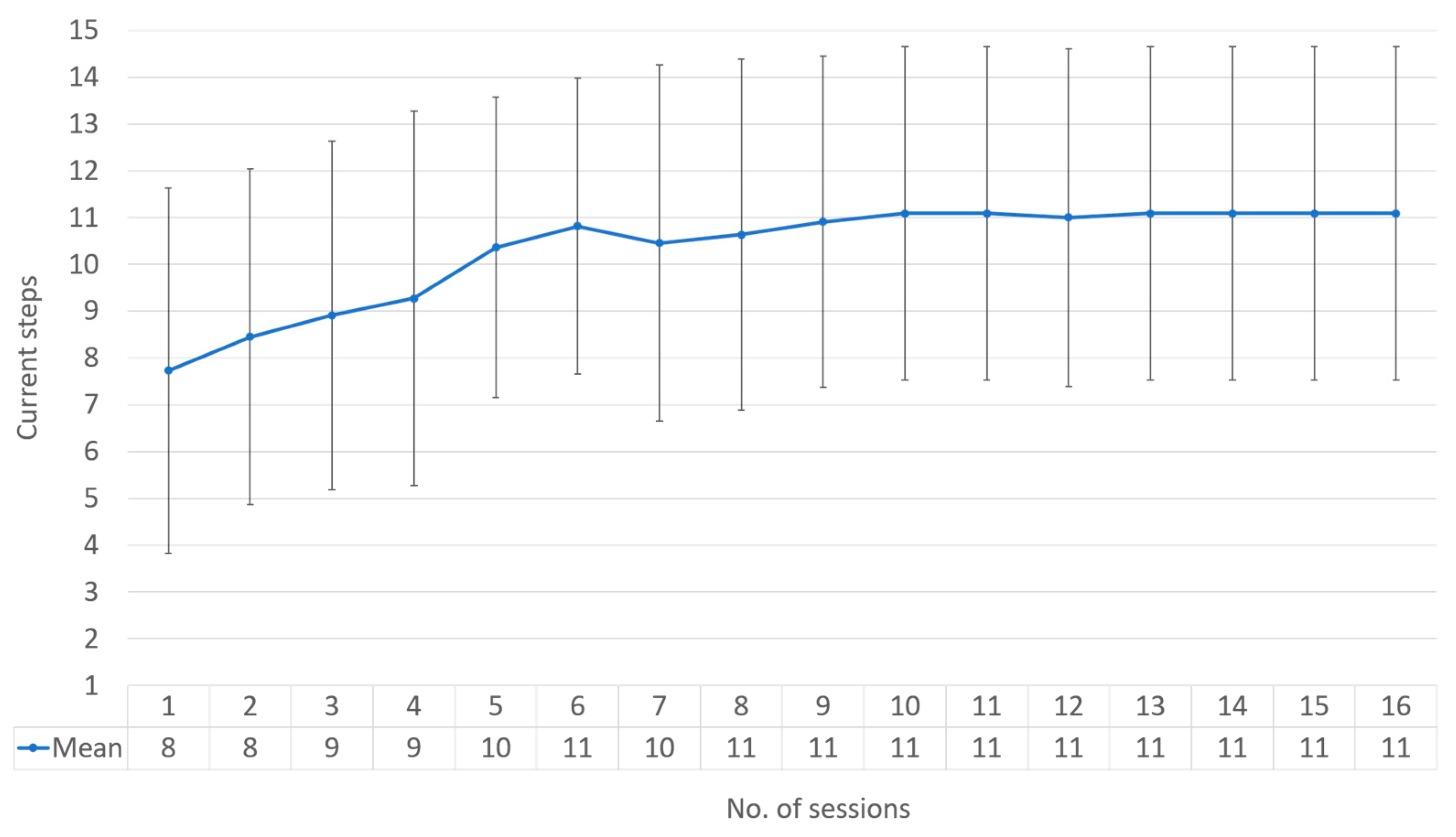

3.1. Hypothesis 1: Familiarization

- The median of the mean sessions: 11;

- Mean of the mean sessions: 11;

- Mean of the standard deviation sessions: 3.562430223.

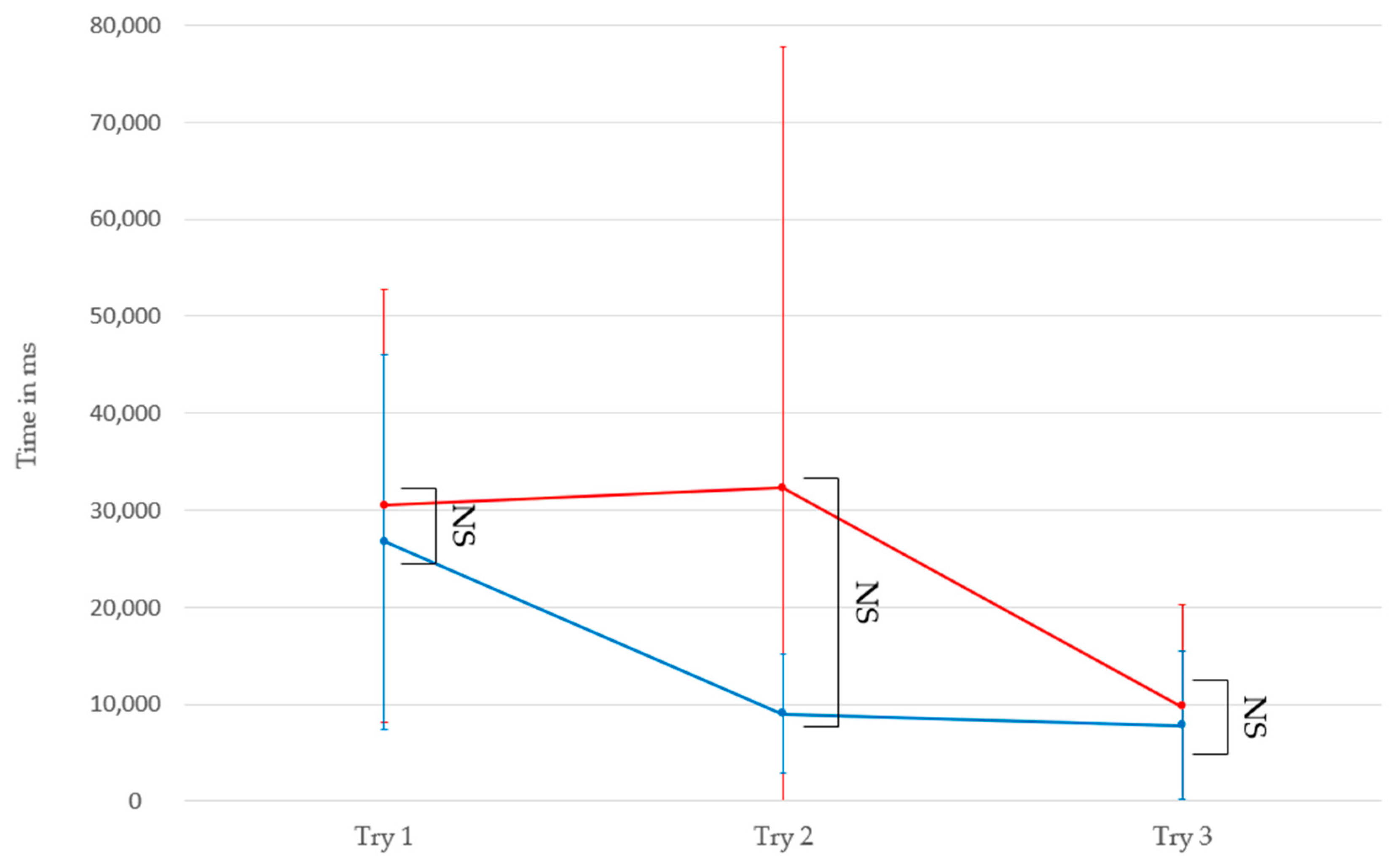

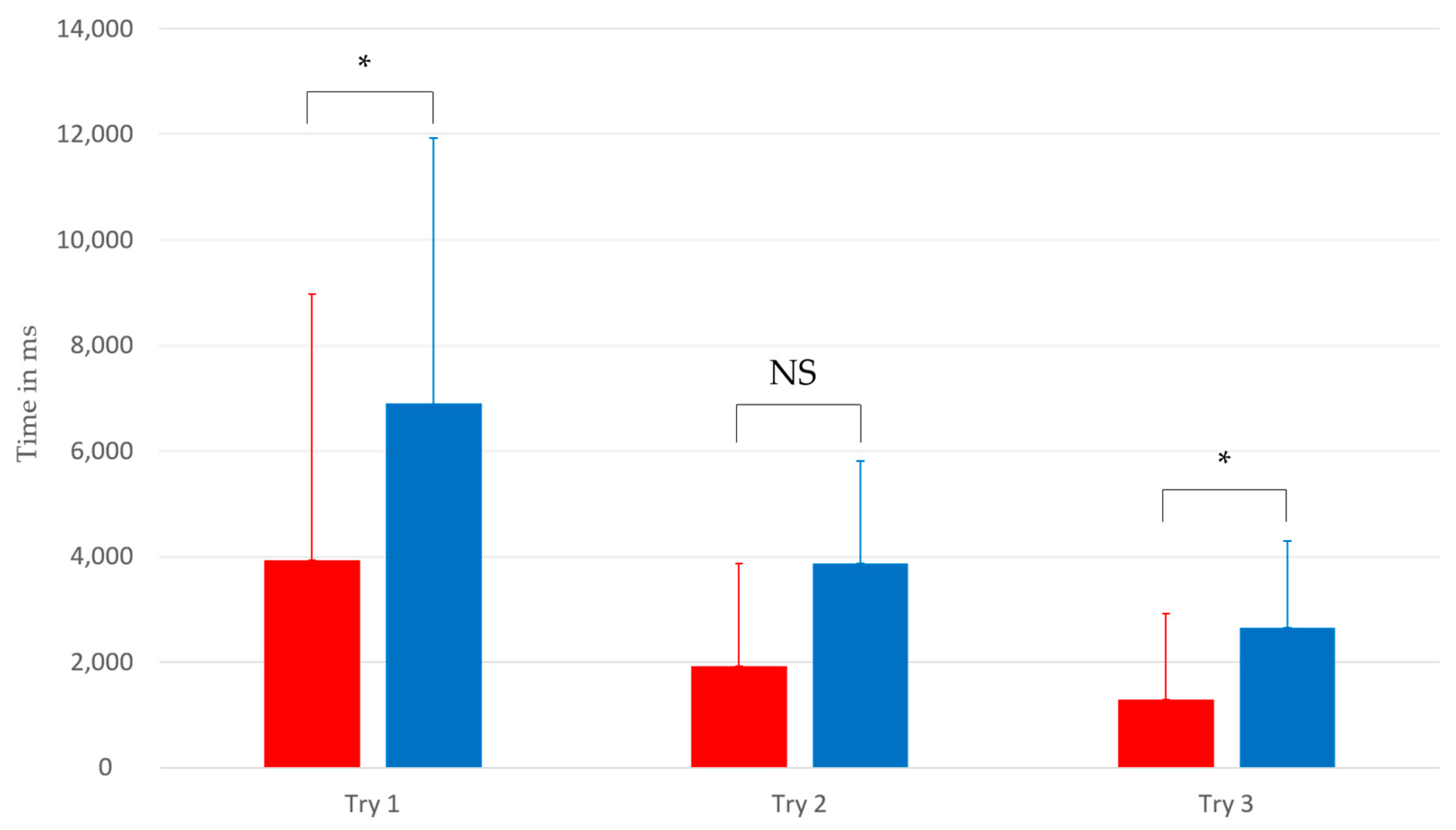

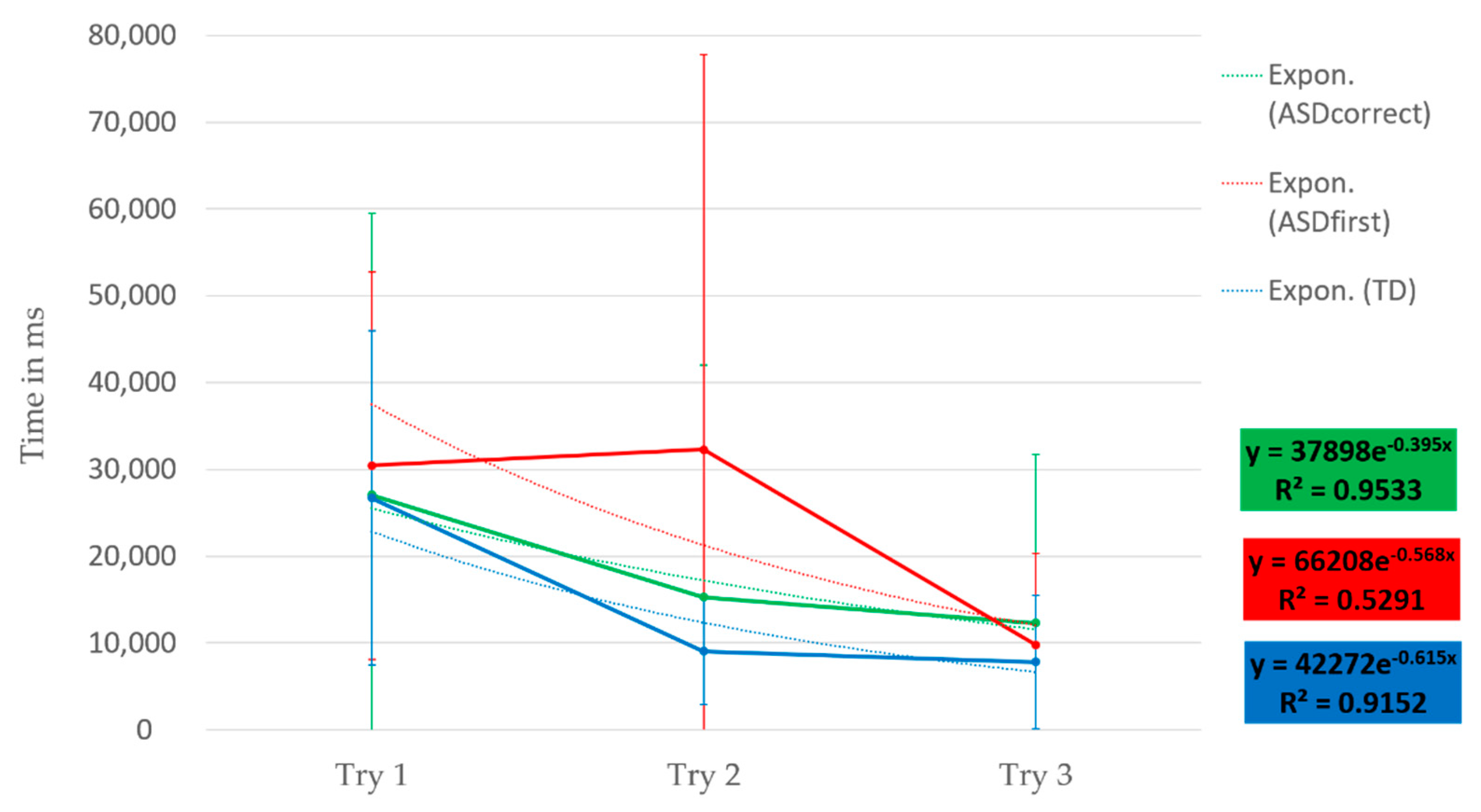

3.2. Hypothesis 2: Intragroup Comparison

3.3. Hypothesis 3: Intergroup Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Familiarization

4.2. Group Comparison

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Pub.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, M.J.; Harris, S.L. Teaching social skills to people with autism. Behav. Modif. 2001, 25, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trémaud, M.; Aguiar, Y.P.; Pavani, J.B.; Gepner, B.; Tardif, C. What do digital tools add to classical tools for socio-communicative and adaptive skills in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder? L’Année Psychol. 2021, 121, 361–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, N. Remédiation Cognitive; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grynszpan, O.; Weiss, P.L.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Gal, E. Innovative technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Autism 2014, 18, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.J.; Colombo, J. Larger tonic pupil size in young children with an autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Psychobiol. 2009, 51, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzotto, F.; Torelli, E.; Vona, F.; Aruanno, B. HoloLearn: Learning through mixed reality for people with cognitive disability. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR), Taichung, Taiwan, 10–12 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 189–190. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes Laurie, M.; Warreyn, P.; Villamia Uriarte, B.; Boonen, C.; Fletcher-Watson, S. An International Survey of Parental Attitudes to Technology Use by Their Autistic Children at Home. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Srinivasan, S.; Pescatello, L.; Therapy, A.B.-P. Current perspectives on physical activity and exercise recommendations for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Physical Therapy 2014, 94, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robins, B.; Dautenhahn, K.; Te Boekhorst, R.; Billard, A. Robots as assistive technology—Does appearance matter? Proc. IEEE Int. Workshop Robot. Hum. Interact. Commun. 2004, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cabibihan, J.J.; Javed, H.; Ang, M.; Aljunied, S.M. Why Robots? A Survey on the Roles and Benefits of Social Robots in the Therapy of Children with Autism. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2013, 5, 593–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scassellati, B.; Admoni, H.; Mataric, M. Robots for autism research. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 14, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kandalaft, M.R.; Didehbani, N.; Krawczyk, D.C.; Allen, T.T.; Chapman, S.B. Virtual reality social cognition training for young adults with high-functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kagohara, D.M.; van der Meer, L.; Ramdoss, S.; O’Reilly, M.F.; Lancioni, G.E.; Davis, T.N.; Rispoli, M.; Lang, R.; Marschik, P.B.; Sutherland, D.; et al. Using iPods® and iPads® in teaching programs for individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grynszpan, O.; Martin, J.-C.; Nadel, J. Multimedia interfaces for users with high functioning autism: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2018, 66, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruanno, B.; Garzotto, F.; Torelli, E.; Vona, F. Hololearn: Wearable Mixed Reality for People with Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDD). In Proceedings of the 20th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Galway, Ireland, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganz, J.B.; Earles-Vollrath, T.L.; Heath, A.K.; Parker, R.; Rispoli, M.J.; Duran, J.B. A meta-analysis of single case studies on aided augmentative and alternative communication systems with individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 37, 1423–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Microsoft. What is Mixed Reality Toolkit 2? 2022. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/fr-fr/windows/mixed-reality/mrtk-unity/mrtk2/?view=mrtkunity-2022-05 (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Speicher, M.; Hall, B.D.; Nebeling, M. What is mixed reality? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. Ieice Trans. Inf. Syst. 1994, 77, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B.; Anisetti, M.; Ceravolo, P.; Damiani, E.; Ivkovic, M. Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2011, 51, 341–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumpouros, Y.; Kafazis, T. Wearables and mobile technologies in autism spectrum disorder interventions: A systematic literature review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 66, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailenson, J.N.; Yee, N.; Blascovich, J.; Beall, A.C.; Lundblad, N.; Jin, M. The use of immersive virtual reality in the learning sciences: Digital transformations of teachers, students, and social context. J. Learn. Sci. 2008, 17, 102–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.K.; Park, J.; Choi, Y.; Choe, M. Virtual reality sickness questionnaire (VRSQ): Motion sickness measurement index in a virtual reality environment. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 69, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanier, J. Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality; Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cilia, F.; Aubry, A.; Le Driant, B.; Bourdin, B.; Vandromme, L. Visual Exploration of Dynamic or Static Joint Attention Bids in Children With Autism Syndrome Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guillon, Q.; Hadjikhani, N.; Baduel, S.; Rogé, B. Visual social attention in autism spectrum disorder: Insights from eye tracking studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 42, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldy, Z.; Kraper, C.; Carter, A.S.; Blaser, E. Toddlers with Autism Spectrum Disorder are more successful at visual search than typically developing toddlers. Dev. Sci. 2011, 14, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Franchini, M.; Glaser, B.; Gentaz, E.; Wood, H.; Eliez, S.; Schaer, M. The effect of emotional intensity on responses to joint attention in preschoolers with an autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2017, 35, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yarbus, A.L. Eye Movements and Vision; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp, S.; Barz, M.; Mukhametov, S.; Sonntag, D.; Kuhn, J. Arett: Augmented reality eye tracking toolkit for head-mounted displays. Sensors 2021, 21, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llanes-Jurado, J.; Marín-Morales, J.; Guixeres, J.; Alcañiz, M. Development and calibration of an eye-tracking fixation identification algorithm for immersive virtual reality. Sensors 2020, 20, 4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáiz-Manzanares, M.C.; Pérez, I.R.; Rodríguez, A.A.; Arribas, S.R.; Almeida, L.; Martin, C.F. Analysis of the learning process through eye tracking technology and feature selection techniques. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordahl, C.W.; Mello, M.; Shen, A.M.; Shen, M.D.; Vismara, L.A.; Li, D.; Harrington, K.; Tanase, C.; Goodlin-Jones, B.; Rogers, S.; et al. Methods for acquiring MRI data in children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual impairment without the use of sedation. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2016, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shabani, D.B.; Fisher, W.W. Stimulus fading and differential reinforcement for the treatment of needle phobia in a youth with autism. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2006, 39, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, J.A. The learning curve, revisited. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Learn. Cogn. 2022, 48, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck-Ytter, T.; Bölte, S.; Gredebäck, G. Eye tracking in early autism research. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2013, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chita-Tegmark, M. Attention Allocation in ASD: A Review and Meta-analysis of Eye-Tracking Studies. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 3, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelphrey, K.A.; Sasson, N.J.; Reznick, J.S.; Paul, G.; Goldman, B.D. Visual scanning of faces in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie-Smith, K.; Riby, D.M.; Hancock, P.J.; Doherty-Sneddon, G. Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) attend typically to faces and objects presented within their picture communication systems. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2014, 58, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vivanti, G.; Trembath, D.; Dissanayake, C. Mechanisms of Imitation Impairment in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungureanu, D.; Bogo, F.; Galliani, S.; Sama, P.; Duan, X.; Meekhof, C.; Stühmer, J.; Cashman, T.J.; Tekin, B.; Schönberger, J.L.; et al. Hololens 2 research mode as a tool for computer vision research. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.11239. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S. Autism: The empathizing-systemizing (E-S) theory. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2009, 1156, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.R.; Handen, B.L.; Butter, E.M.; Sacco, K. Continuity of adaptive behaviors from early childhood to adolescence in autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Cascio, C.J.; Foss-Feig, J.H.; Burnette, C.P.; Heacock, J.L.; Cosby, A.A. The rubber hand illusion in children with autism spectrum disorders: Delayed influence of combined tactile and visual input on proprioception. Autism 2012, 16, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolognini, N.; Russo, C.; Vallar, G. Crossmodal illusions in neurorehabilitation. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrold, C.; Boucher, J.; Smith, P. Symbolic play in autism: A review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1993, 23, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, H.; Kuchenbecker, K.J. Importance of Matching Physical Friction, Hardness, and Texture in Creating Realistic Haptic Virtual Surfaces. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2017, 10, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazefsky, C.A.; Borue, X.; Day, T.N.; Minshew, N.J. Emotion regulation in adolescents with ASD. Autism Res. 2014, 7, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koegel, R.L.; Koegel, L.K. Pivotal Response Treatments for Autism: Communication, Social, & Academic Development; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khowaja, K.; Salim, S.S. The use of virtual reality technology in the treatment of autism: A case study. In Proceedings of the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility, Rochester, NY, USA; 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G.; Burner, K. Behavioral interventions in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A review of recent findings. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2011, 23, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelle, L.E. The learning curve: Historical review and comprehensive survey. Decis. Sci. 1979, 10, 302–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmajuk, N.A. Learning by Occasion Setting. Neuroscience 2001, 108, 835–847. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano, E. The Development of Core Cognitive Skills in Autism: A 3-Year Prospective Study. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 1400–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanti, G.; Rogers, S.J. Autism, and the mirror neuron system: Insights from learning and teaching. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2014, 369, 20130184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bast, N.; Poustka, L.; Freitag, C.M. The locus coeruleus–norepinephrine system as pacemaker of attention—A developmental mechanism of derailed attentional function in autism spectrum disorder. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 47, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzanello, M.J.; Fogliatto, F.S. Learning curve models and applications: Literature review and research directions. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2011, 41, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S.L.; Collet-Klingenberg, L.; Rogers, S.J.; Hatton, D.D. Evidence-Based Practices in Interventions for Children and Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Prev. Sch. Fail. Altern. Educ. Child. Youth 2010, 54, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Age (Years) | Gender | Vineland-II (Standard Note Sum) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001PR | 25 | Male | 30 | ASD |

| 002FV | 22 | Male | 20 | ASD |

| 003FM | 28 | Female | 20 | ASD |

| 004TM | 19 | Male | 37 | PDD * with language disorder |

| 005RK | 19 | Male | 56 | PDD * atypical disorder |

| 006TC | 28 | Male | 20 | ASD |

| 007HC | 25 | Male | 20 | ASD |

| 008ST | 14 | Male | 20 | ASD |

| 009MA | 15 | Male | 23 | ASD |

| 010DF | 30 | Male | 20 | ASD |

| 011BN | 40 | Female | 20 | ASD |

| Type of Familiarization | Steps |

|---|---|

| Headset Familiarization | 1. Headset Presentation |

| 2. Touch HoloMax | |

| 3. Wear HoloMax for a few seconds | |

| 4. Wear HoloMax for a few minutes | |

| 5. Move around with HoloMax | |

| 6. Move around with the HoloLens 2 | |

| Mixed Reality Familiarization | 7. View holograms |

| 8. Interact with holograms | |

| 9. Eye Tracking Calibration | |

| 10. Touch in the tutorial | |

| 11. Move to the tutorial | |

| 12. Enlarge in the tutorial | |

| 13. Shrink in the tutorial | |

| 14. Pivot in the tutorial |

| Group | p Value for Differences in Fixation Duration on the Main Hologram during Task 1 | p Value Regarding Runtime Differences on the Main Hologram during Task 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.069 × 10−13 | 1.587 × 10−11 |

| With ASD | 0.131 | 0.03192 |

| Execution Times | Try n°1 vs. n°2 | Try n°1 vs. n°3 | Try n°2 vs. n°3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | p value = 1.9 × 10−5 | p value = 2.9 × 10−11 | p value = 0.056 |

| Group with ASD | p value = 0.613 | p value = 0.026 | p value = 0.225 |

| Fixation Duration | Try n°1 vs. n°2 | Try n°1 vs. n°3 | Try n°2 vs. n°3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | p value = 3.4 × 10−8 | p value = 1.1 × 10−12 | p value = 0.26 |

| Group with ASD | p value = 0.27 | p value = 0.13 | p value = 0.92 |

| NT vs. TSA | Try n°1 | Try n°2 | Try n°3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Execution times | p value = 0.6251 | p value = 0.4691 | p value = 0.2505 |

| Fixation duration | p value = 0.03422 | p value = 0.1112 | p value = 0.01384 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leharanger, M.; Rodriguez Martinez, E.A.; Balédent, O.; Vandromme, L. Familiarization with Mixed Reality for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Eye Tracking Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23146304

Leharanger M, Rodriguez Martinez EA, Balédent O, Vandromme L. Familiarization with Mixed Reality for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Eye Tracking Study. Sensors. 2023; 23(14):6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23146304

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeharanger, Maxime, Eder Alejandro Rodriguez Martinez, Olivier Balédent, and Luc Vandromme. 2023. "Familiarization with Mixed Reality for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Eye Tracking Study" Sensors 23, no. 14: 6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23146304

APA StyleLeharanger, M., Rodriguez Martinez, E. A., Balédent, O., & Vandromme, L. (2023). Familiarization with Mixed Reality for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Eye Tracking Study. Sensors, 23(14), 6304. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23146304