Analysis of Constraints on the Remote Application of Inverse Synthetic Aperture Laser Radar

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Basic Principle

2.1. ISAL (Space-Based) Remote Detection Principle

2.2. Coherent Detection Principle

3. Simulation Analysis of the Core Influencing Factors on Remote Applications

3.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Laser Power on Remote Applications

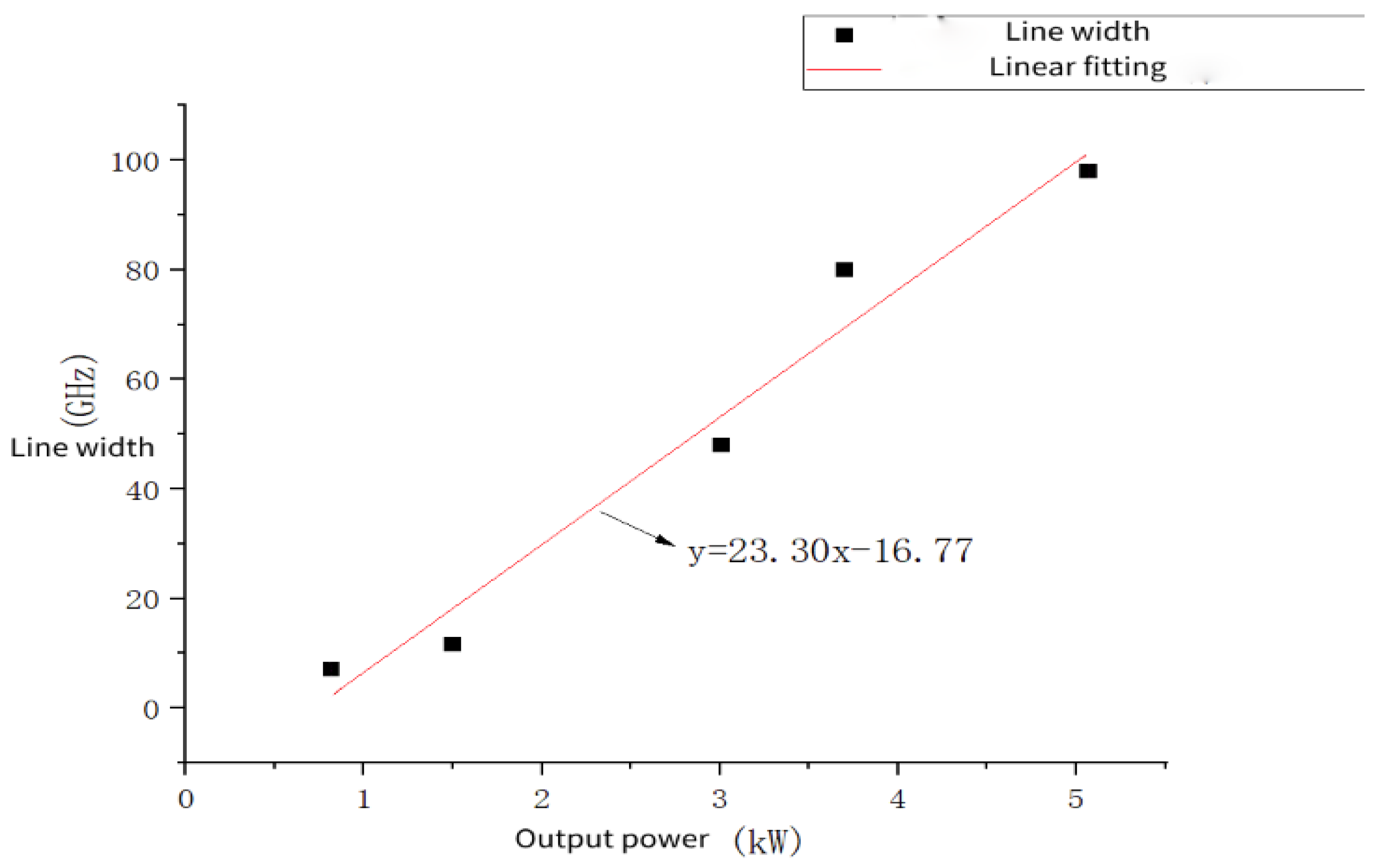

3.1.1. Analysis of Influence Factors on Power of Continuous Fiber Laser

3.1.2. Analysis of Influence Factors of Pulsed Laser Power

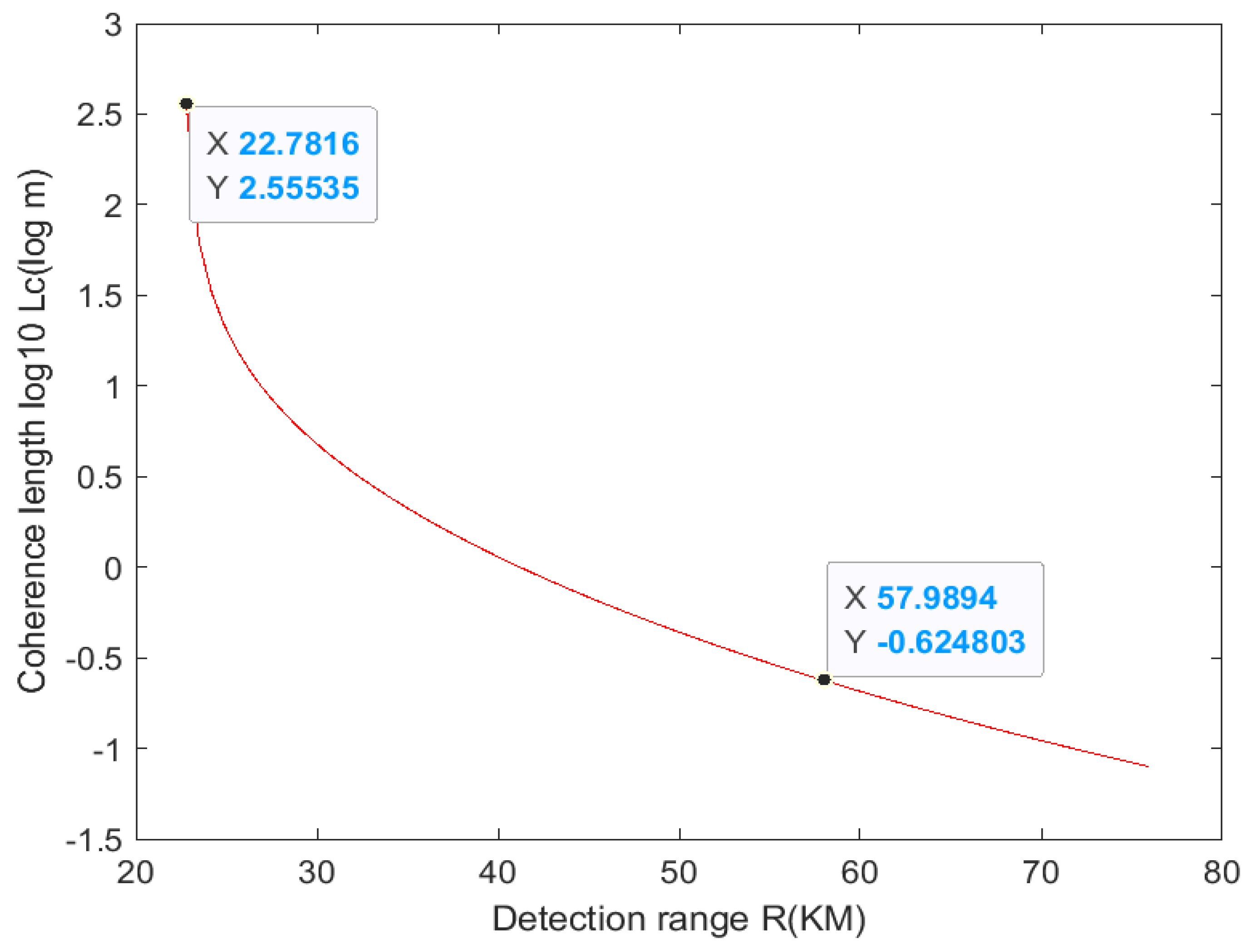

3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Coherence on Remote Applications

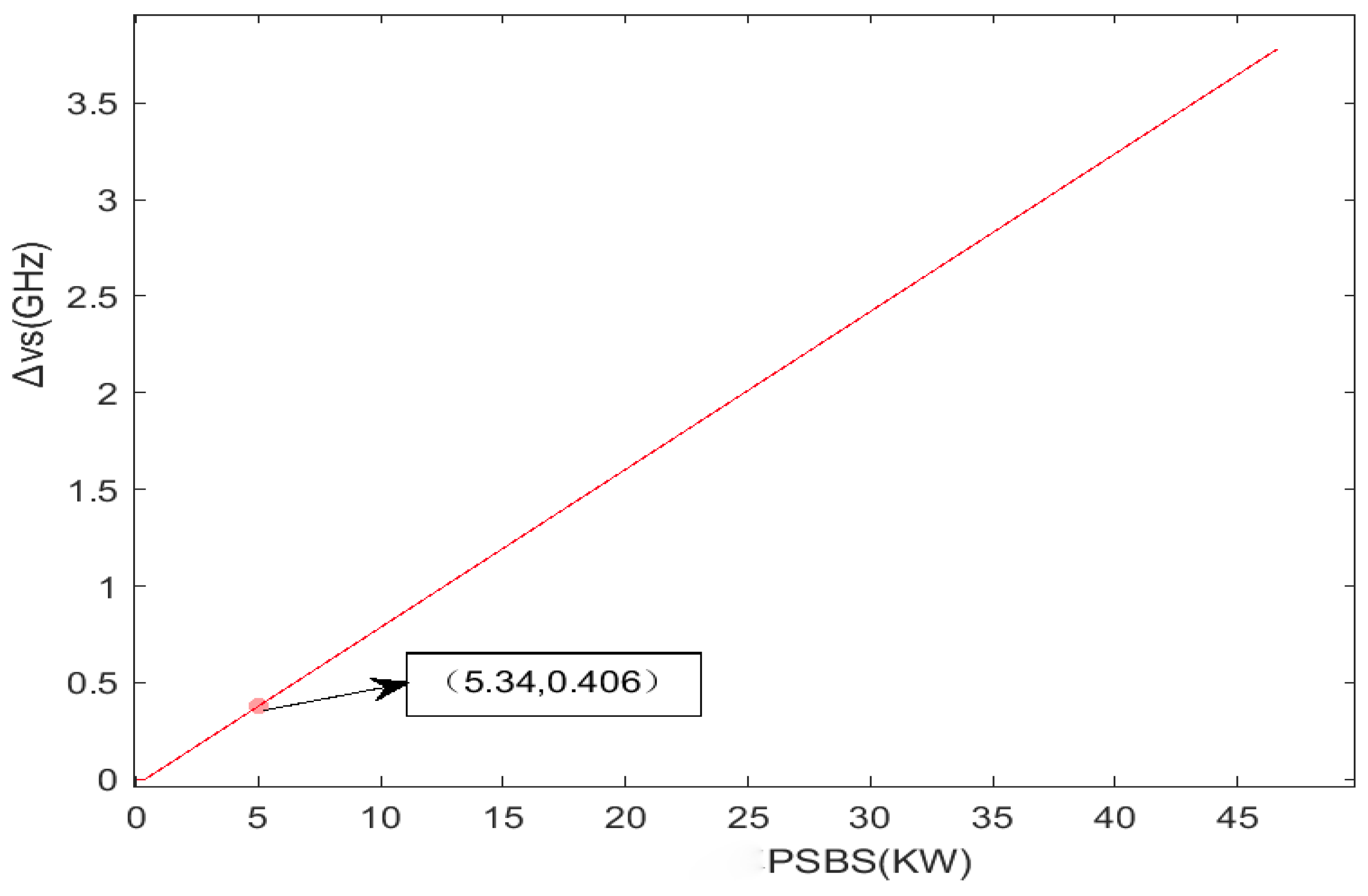

3.2.1. Analysis of Factors Affecting Coherence of Continuous Fiber Lasers

3.2.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Coherence of Pulsed Laser

4. Coherence Compensation Scheme

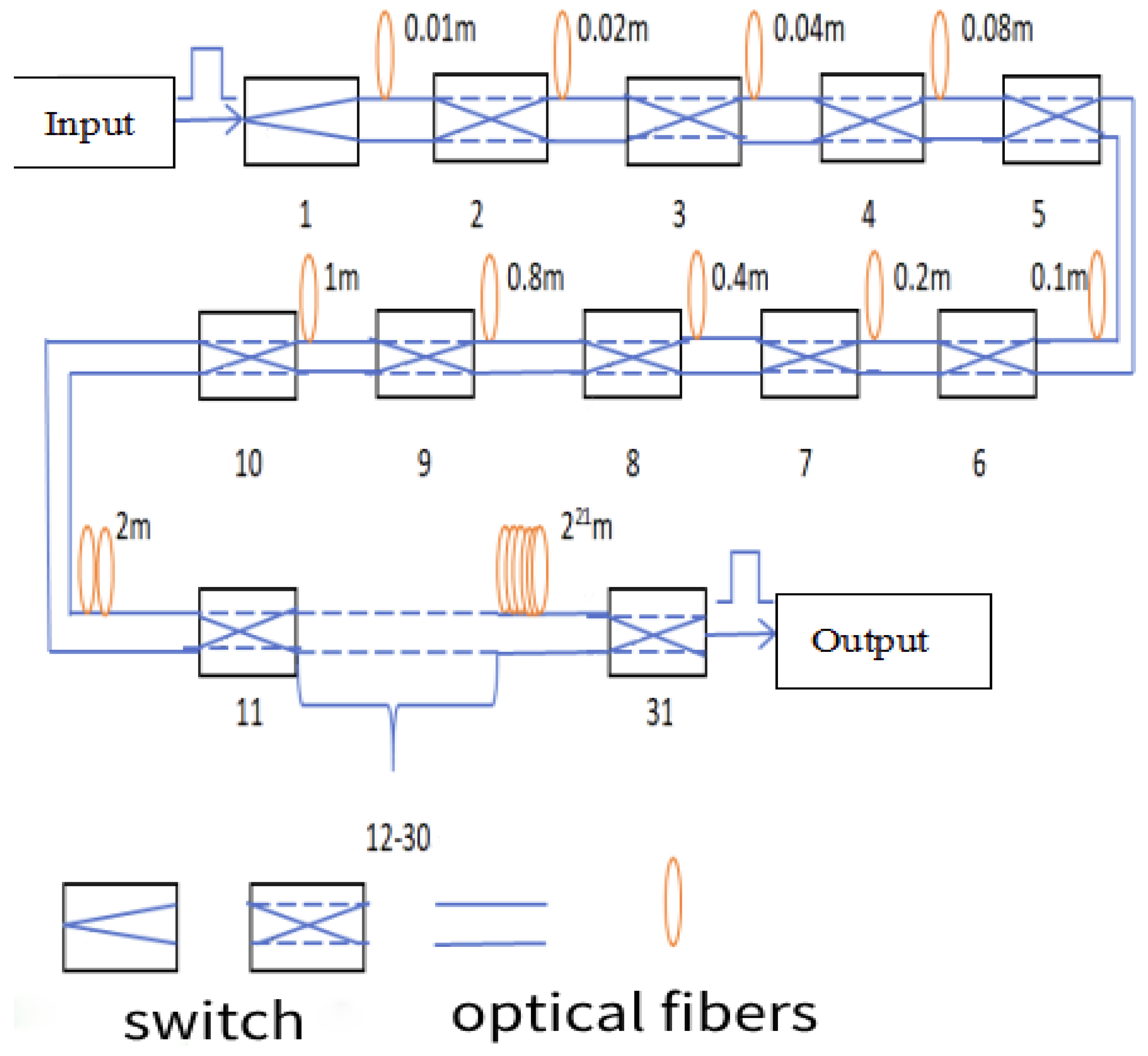

4.1. Large-Travel Fast-Variable Fiber Delay Line Topology Based on Magneto-Optic Switch

4.2. Other Coherence Compensation Methods

5. Conclusions

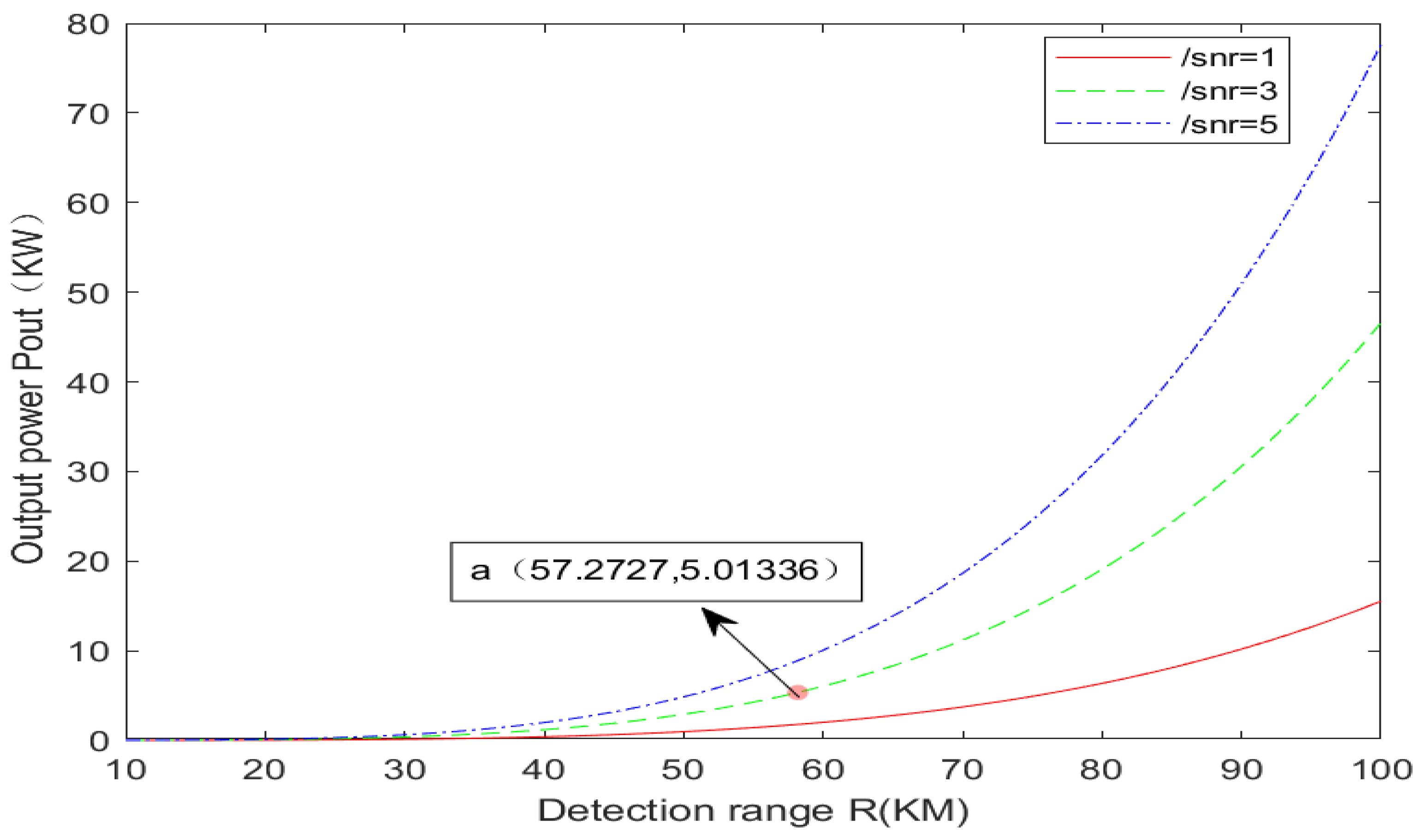

- (1)

- The remote detection performance of fiber lasers is being studied. The simulation results show that the continuous fiber laser can be used to detect operating distances of 22 km and below without compensation. Between 22 km and 57 km, coherent compensation is required.

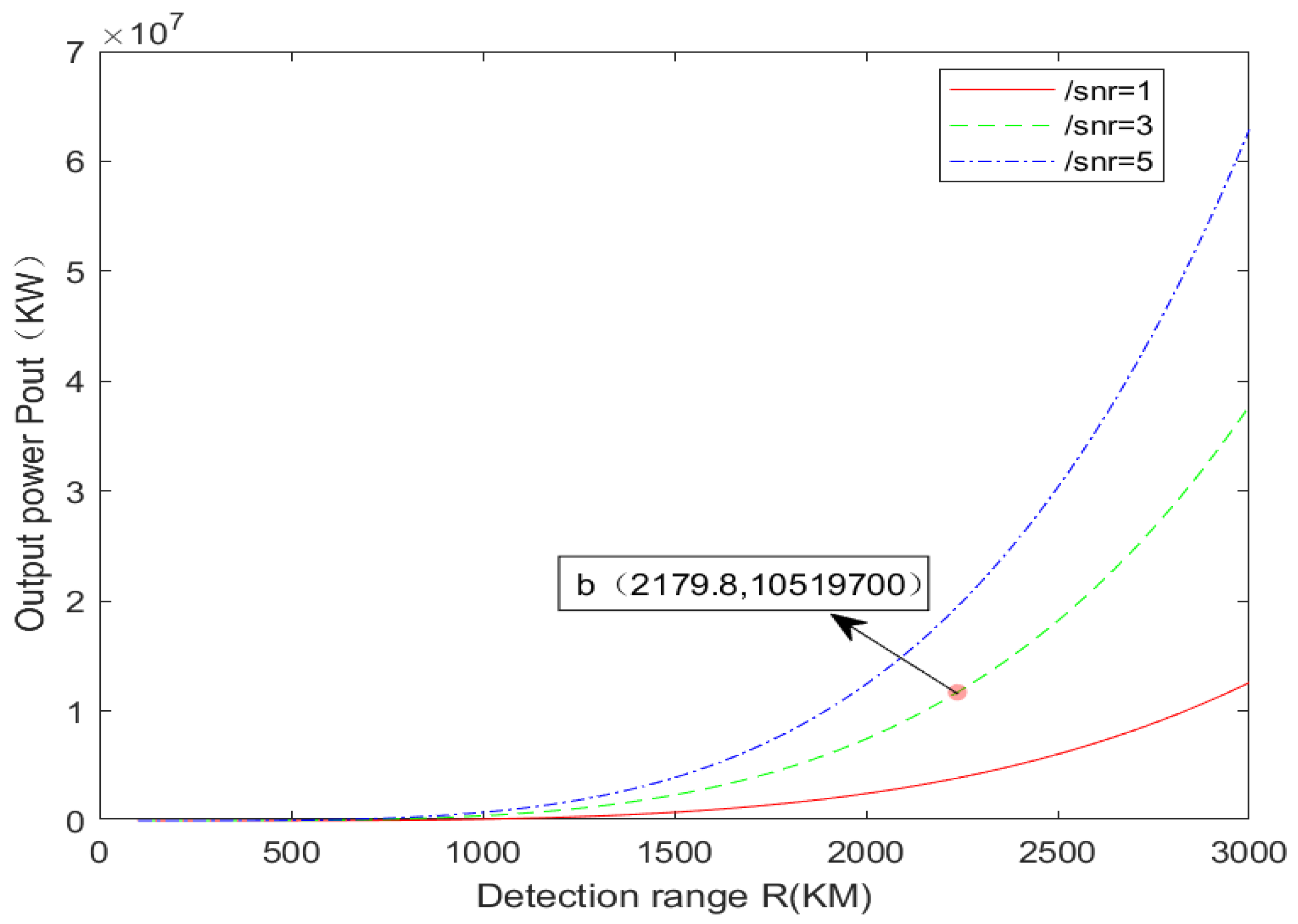

- (2)

- By choosing a pulsed solid-state laser to adjust the coherence length within the range of 57 km to 3000 km, while considering the limited pulse width and SBS threshold power, it is determined that coherence compensation is necessary for distances spanning from 57 km to 3000 km. In addition, it is proposed that an angle reflector (cooperative target) can be used to reduce the power demand for detection, thus enabling longer distance detection. The text explains the difficulty of compensation for cooperative and non-cooperative goals, respectively.

- (3)

- Some mature schemes for optical coherence compensation are presented.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, C. Modeling and Experimental Study of Long-Range Inverse Synthetic Aperture LiDAR System. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Xie, P.; Zhang, L.; Cong, Y. ISAR-NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields for 3-D Imaging of Space TargetFrom Multiview ISAR Images. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 11705–11722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Liu, H.; Wei, J. GEO Targets ISAR Imaging with Joint Intra-Pulse and Inter-Pulse High-Order Motion Compensation and Sub-Aperture Image Fusion at ULCPI. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Chen, Z. Interferometric ISAR Imaging of Space Targets Using Pulse-Level Image Registration Method. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 59, 2188–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Pu, W.; Huo, J.; Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, J. Deep Parametric Imaging for Bistatic SAR: Model, Property and Approach. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Research on Synthetic Aperture Lidar Error Compensation and Processing. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, M.Y. Study on High Power Narrow Linewidth Fiber Laser for Remote Coherent Detection. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xian, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.B.; Peng, R.L. Principle and Application of Laser, 3rd ed.; Publishing House of Electronics Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q. Research on 1.0 μm High Power Narrow Linewidth Fiber Laser. Ph.D. Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangdong, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.Y.; Feng, T.-A.; Zheng, W.-Z. Modeling and imaging simulation of inverse synthetic aperture imaging LiDAR system. J. Syst. Simul. 2012, 24, 632–637. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Li, D.; Zhou, K.; Cui, A.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Tan, S.; Gao, Y.; Yao, Y. Analysis of Receiving beam broadening and Operating range of laser radar in diffractive optical system. Chin. J. Lasers 2023, 50, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.-M.; Shu, Q.; Tao, R.-M.; Chu, Q.-H.; Luo, Y.; Yan, D.-L.; Feng, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.-J.; Zhang, H.-Y.; et al. >5 kW record high power narrow linewidth laser from traditional step-index monolithic fiber amplifier. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2021, 33, 1181–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wang, J.; Peng, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Ma, Y.; Fu, B.; Yu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, L.; et al. Research progress and prospect of diode-pumped high energy laser. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2022, 34, 96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, J.W. Statistical Optics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M. Simulation Research on Long Distance Laser Ranging Based on Variable Fiber Delay Line. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Li, D.J.; Zhao, X.F. Coherent preservation method of synthetic aperture Lidar signal based on local oscillator digital delay. Chin. J. Lasers 2018, 45, 236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.R. Principle of double curved wavefront differential self-scanning direct vision synthetic aperture laser imaging radar. Acta Opt. Sin. 2015, 35, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

| Physical Parameter | Physical Meaning | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| SNR | Image signal-to-noise ratio | 1/3/5 dB |

| Target backscatter solid angle | π | |

| Electronic noise figure | 3 dB | |

| Atmospheric transmittance | 1 | |

| System loss | 0.18 | |

| Pulse width | 5 μs | |

| Transmission gain | 33.5 × 106 | |

| Target scattering area | 2.5 × 10−4 m2 | |

| Effective receiving area of the telescope | 4π m2 |

| Physical Parameter | Physical Meaning | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| K | Polarization-dependent factor | 1 |

| G | Brillouin gain coefficient | 25.9686 |

| Aeff | Optical fiber mode field area | 7.07 × 10−10 m2 |

| gB | Peak Brillouin gain | 5 × 10−11 m/W |

| ∆νB | Brillouin scattered light bandwidth | 30 MHz |

| Leff | Effective length of fiber | 0.998 m |

| Detection Range | Compensating Distance | Compensation Accuracy | Simultaneous Switch |

|---|---|---|---|

| 57 km | 114 km | 2 | 26, 25, 23, 22, 21, 20, 18, 16, 14 |

| 652 km | 1304 km | 6 | 30, 27, 26, 25, 24, 23, 20, 18, 17, 16 |

| 1000 km | 2000 km | 2 | 30, 29, 28, 27, 25, 20, 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, R.; Dong, L. Analysis of Constraints on the Remote Application of Inverse Synthetic Aperture Laser Radar. Sensors 2024, 24, 3381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113381

Gao R, Dong L. Analysis of Constraints on the Remote Application of Inverse Synthetic Aperture Laser Radar. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113381

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Rui, and Lei Dong. 2024. "Analysis of Constraints on the Remote Application of Inverse Synthetic Aperture Laser Radar" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3381. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113381