Sea Surface Height Measurements Based on Multi-Antenna GNSS Buoys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

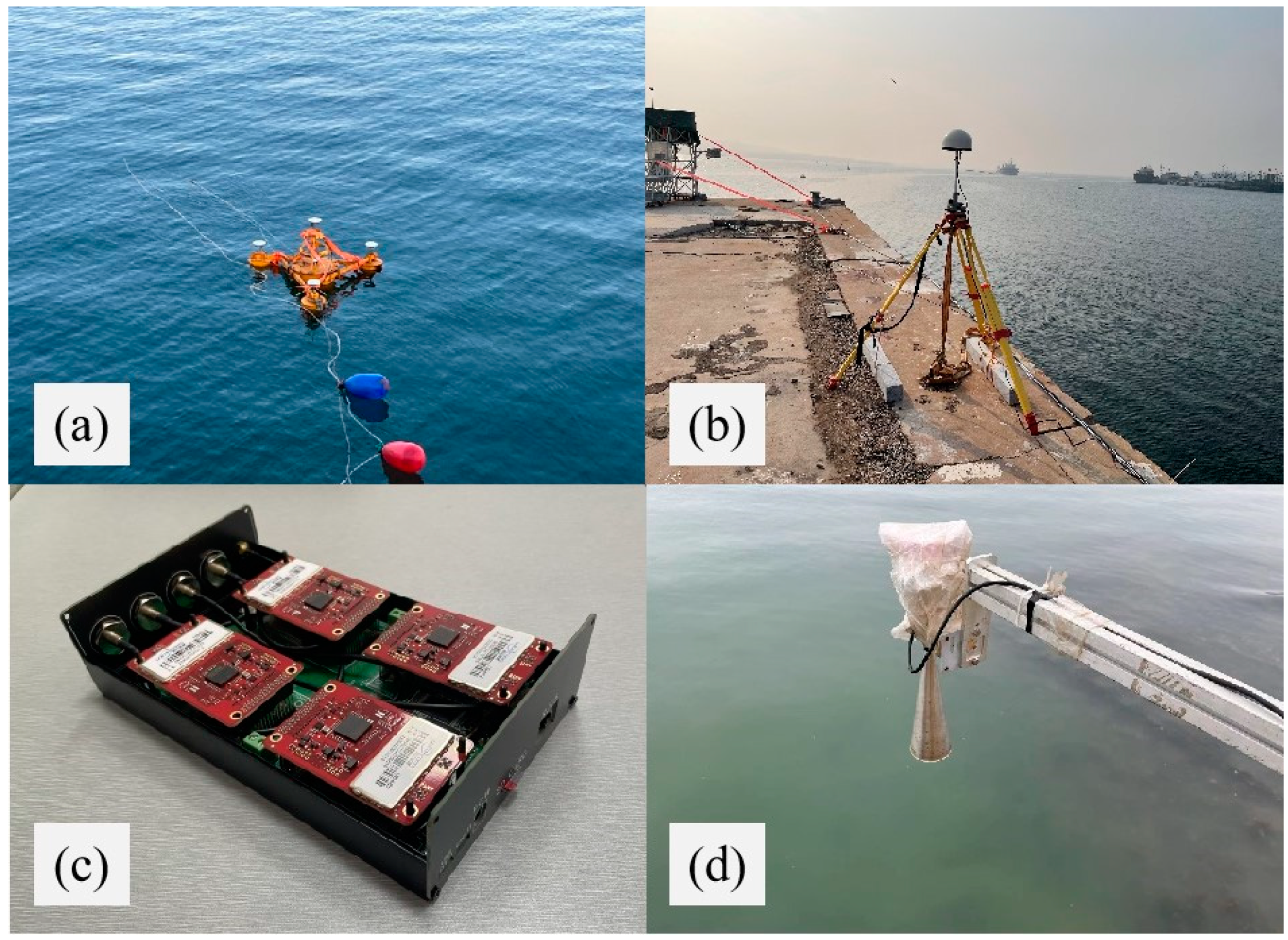

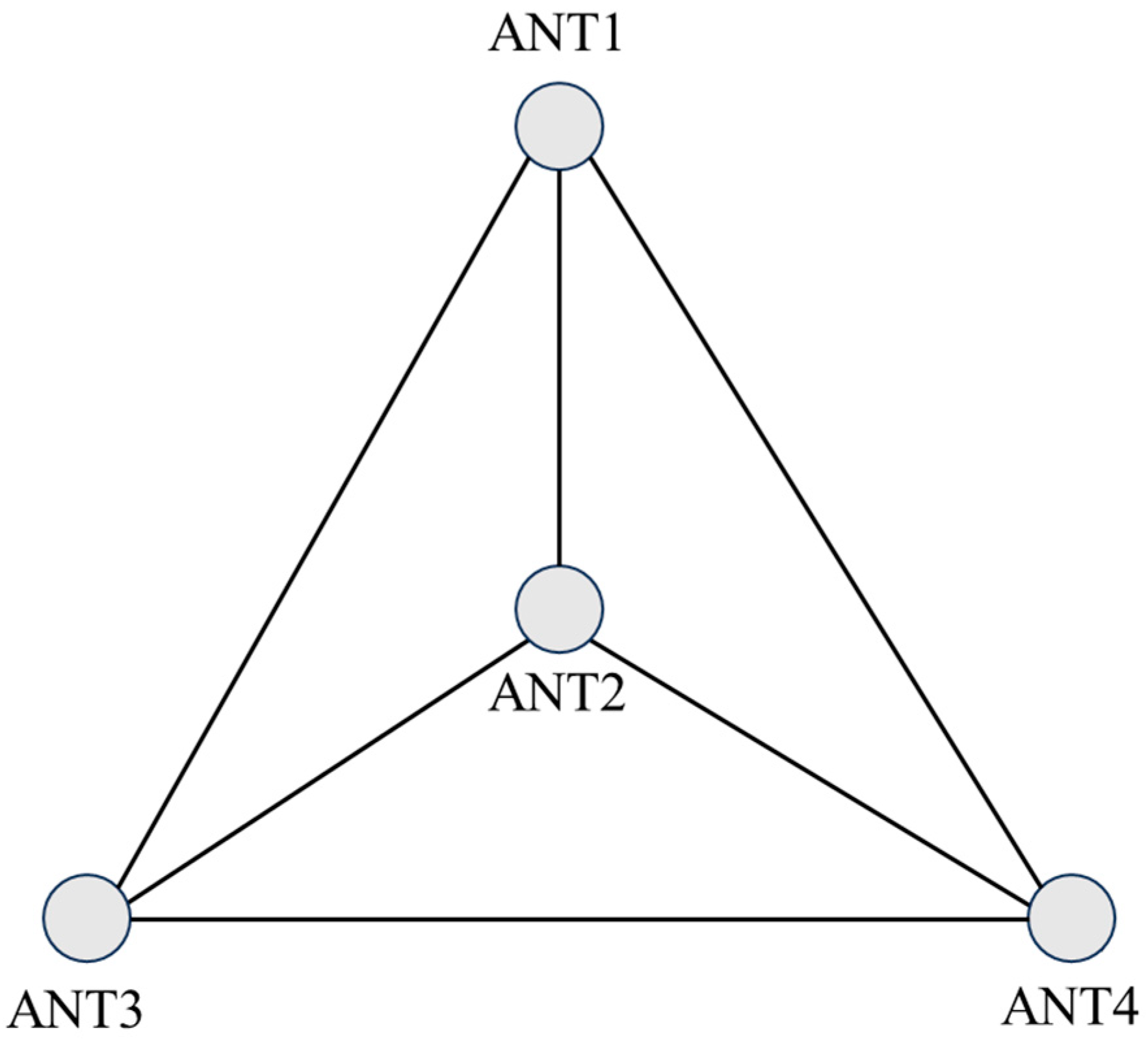

2.1. Multi-Antenna GNSS Buoy Design

2.2. Experiment Introduction

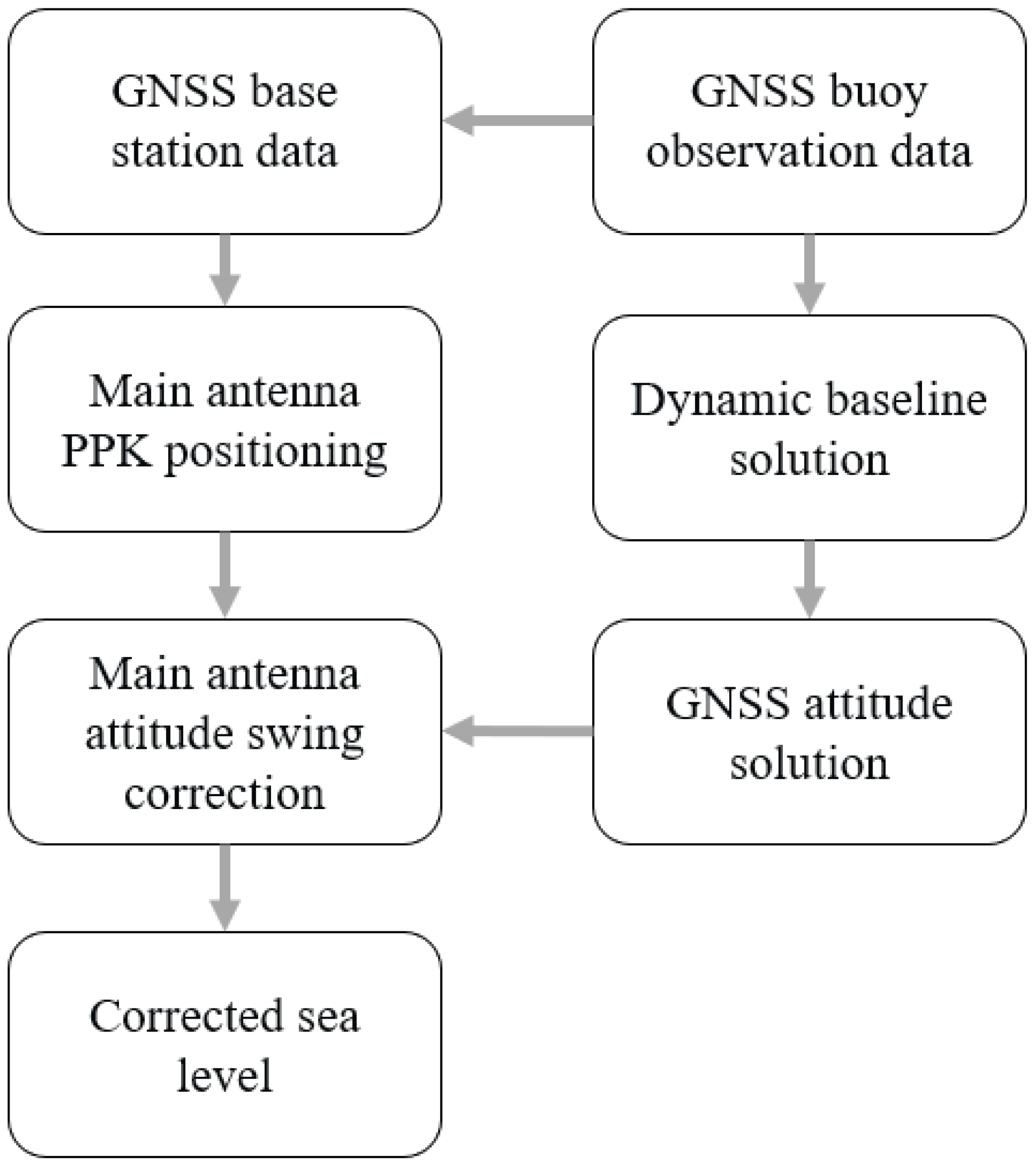

2.3. GNSS Data Processing

3. Results

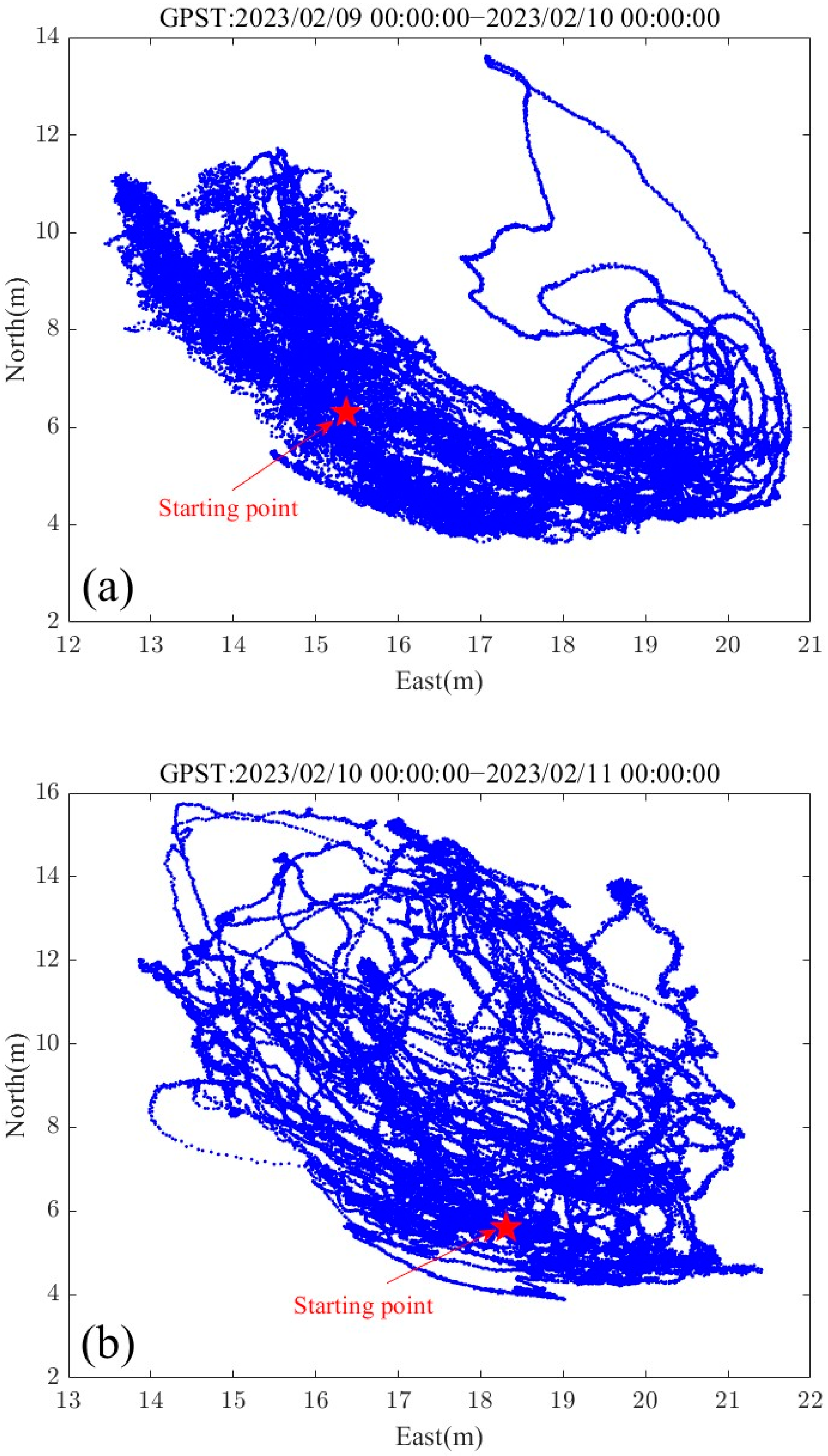

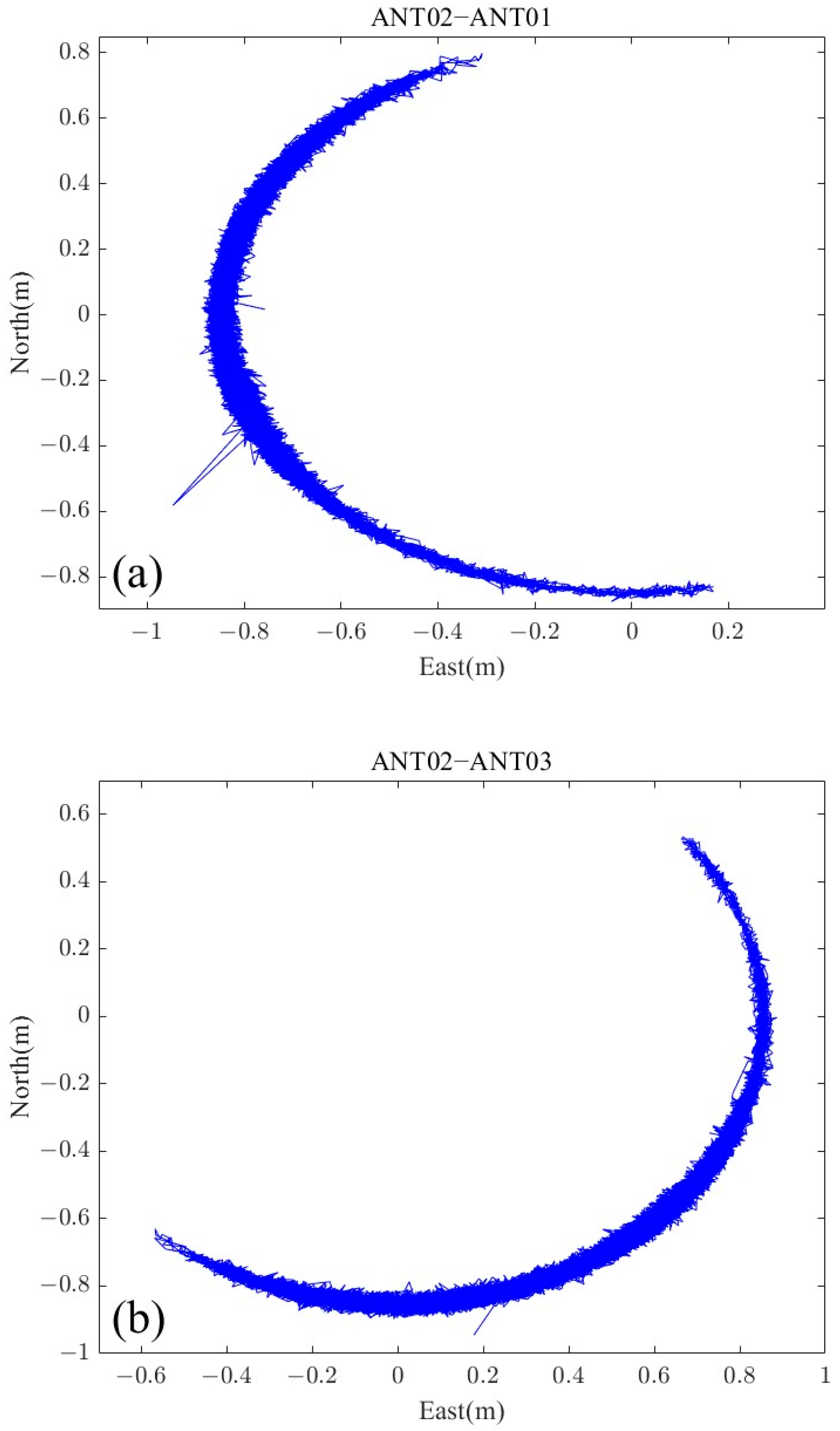

3.1. GNSS Buoy Trajectory

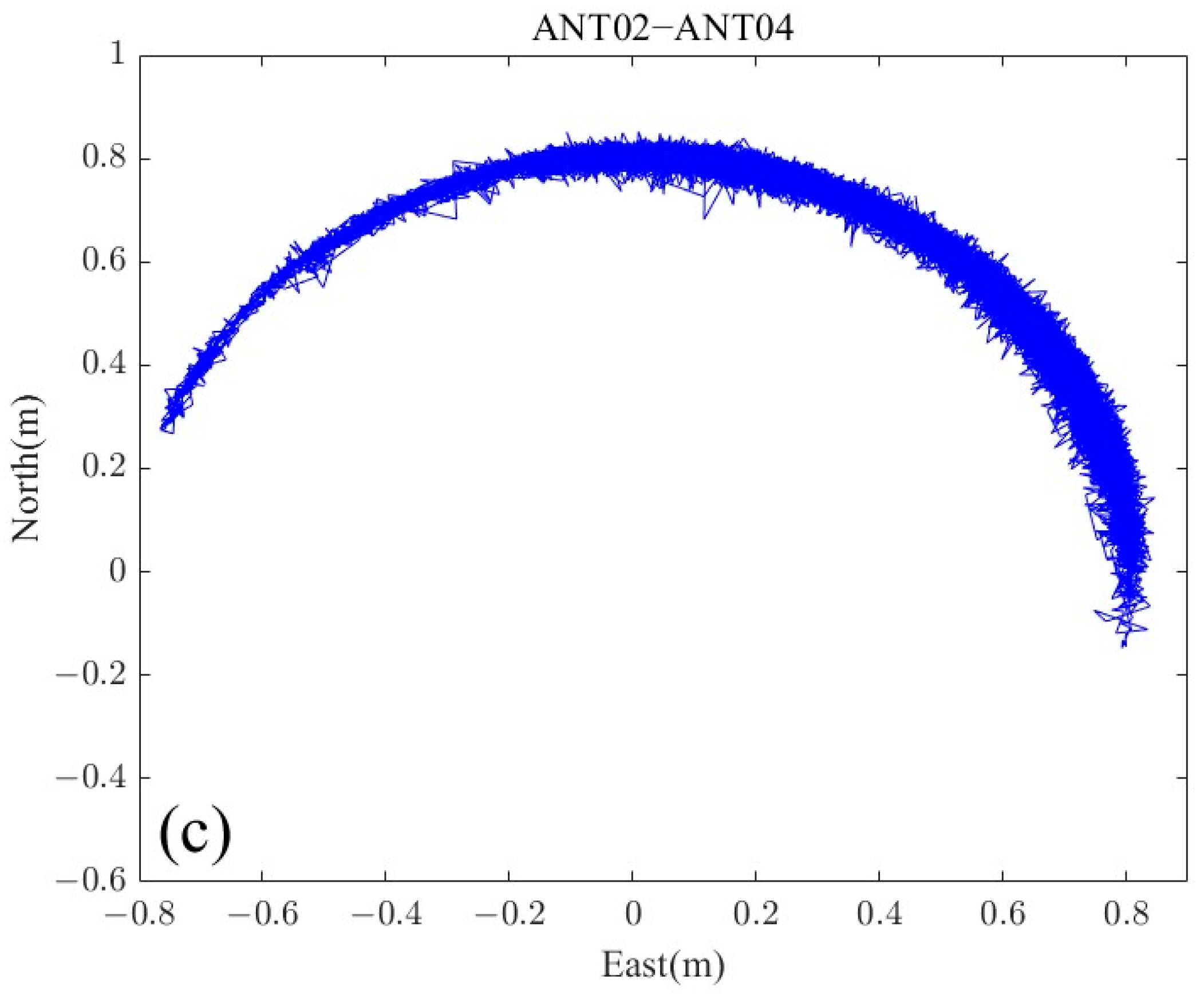

3.2. GNSS Attitude Measurements

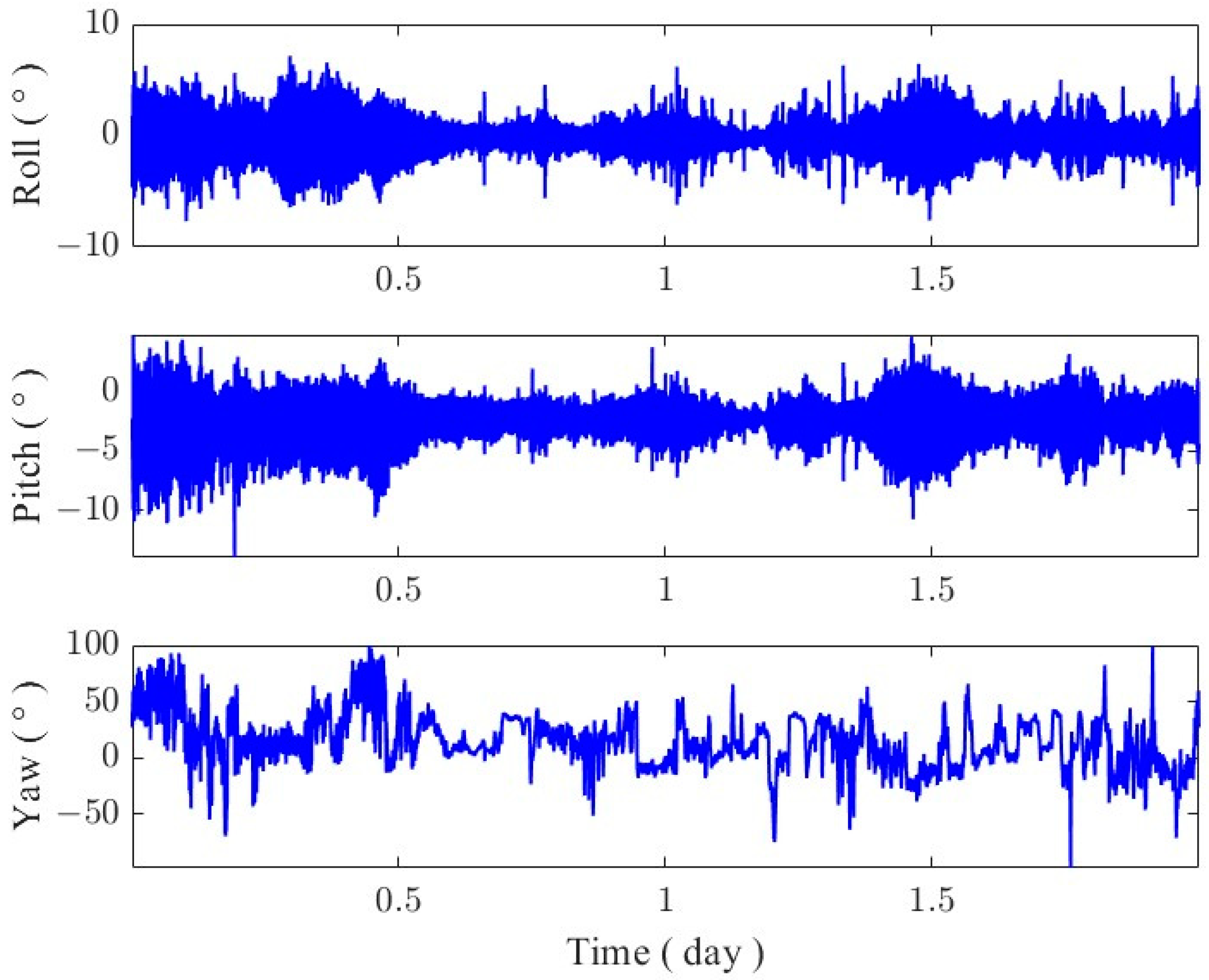

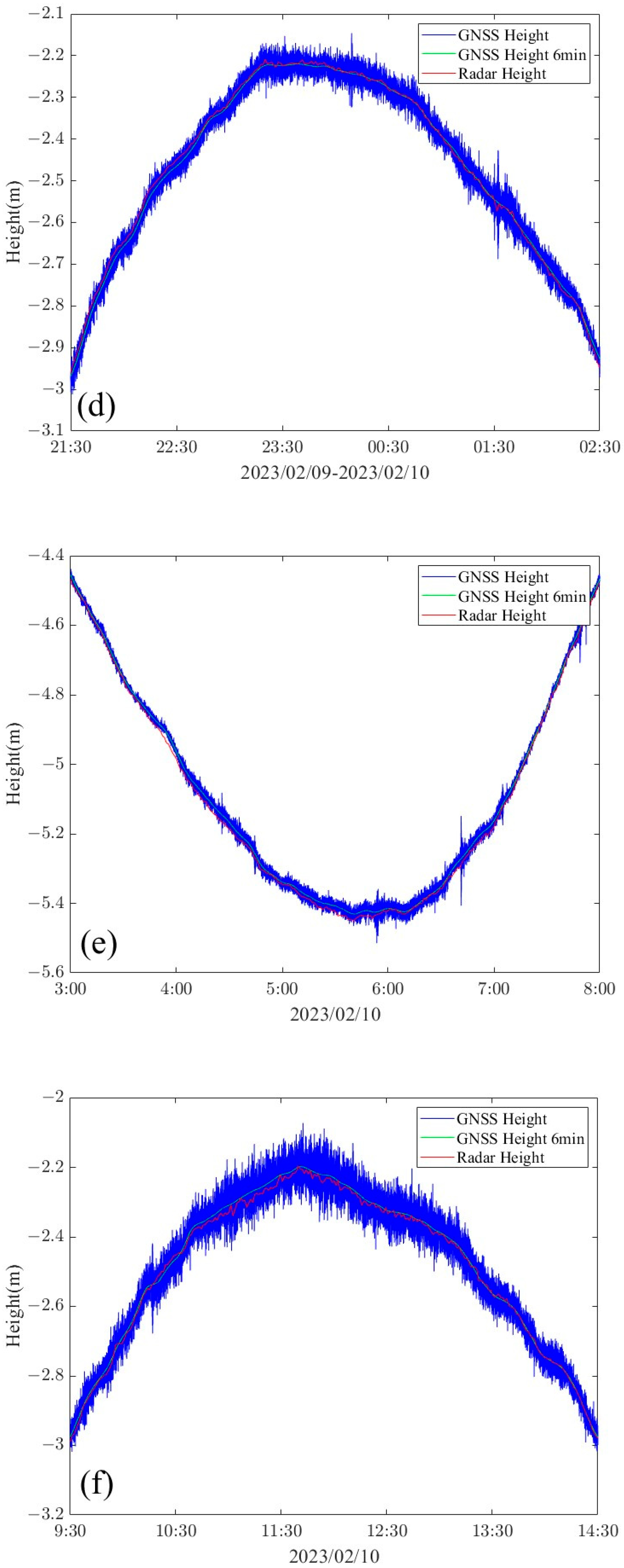

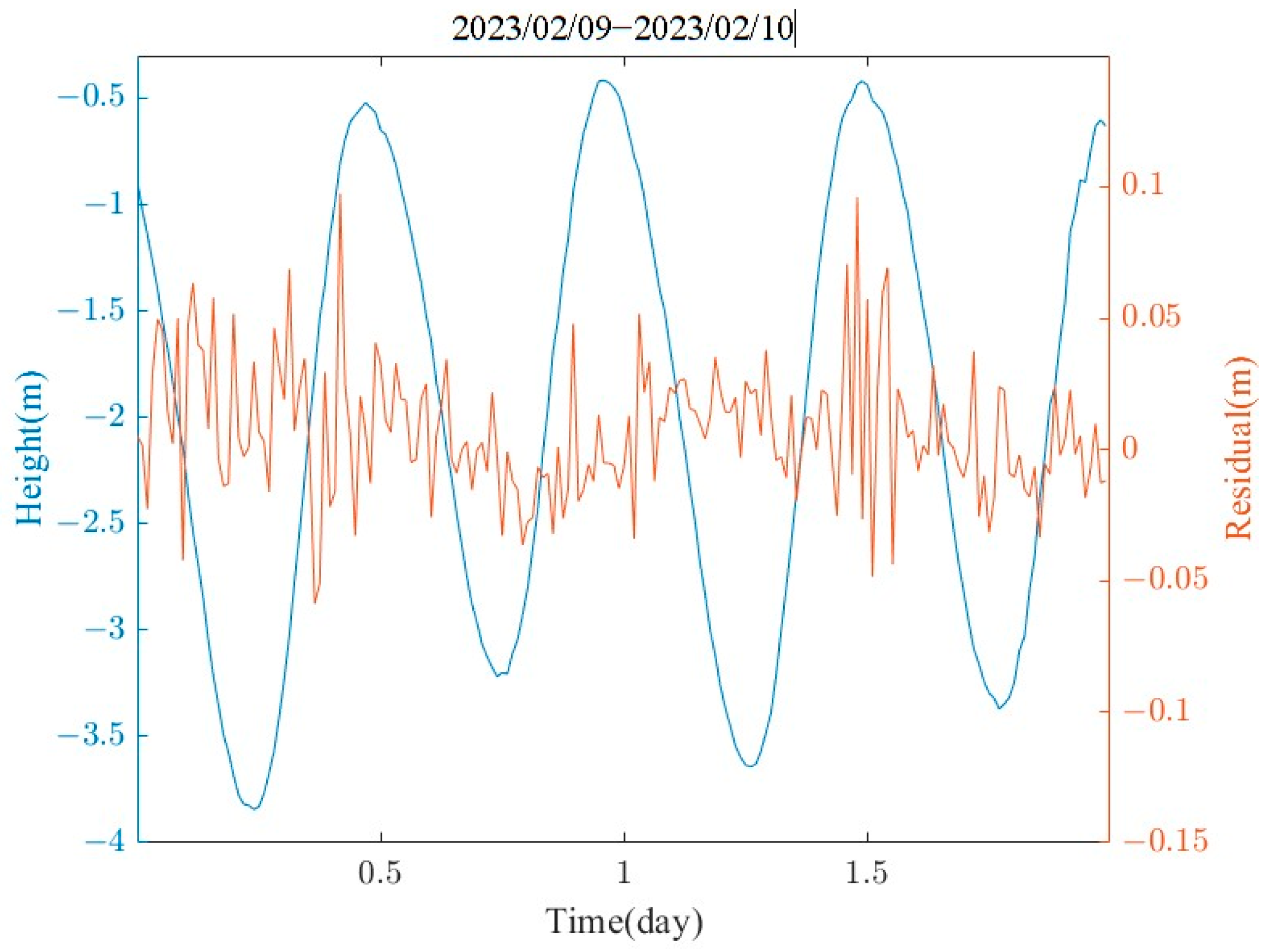

3.3. Comparison of GNSS and Altimetry Radar Data

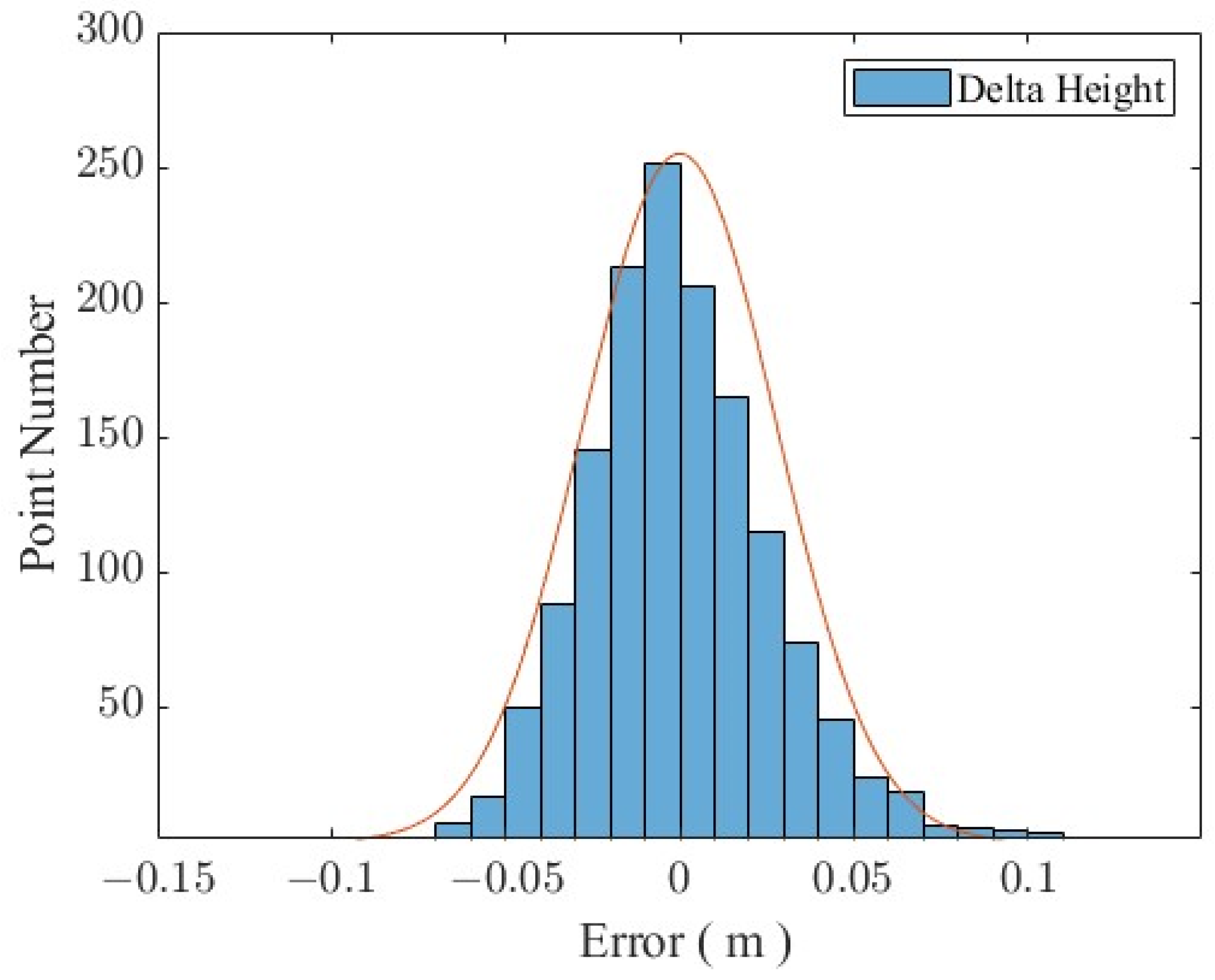

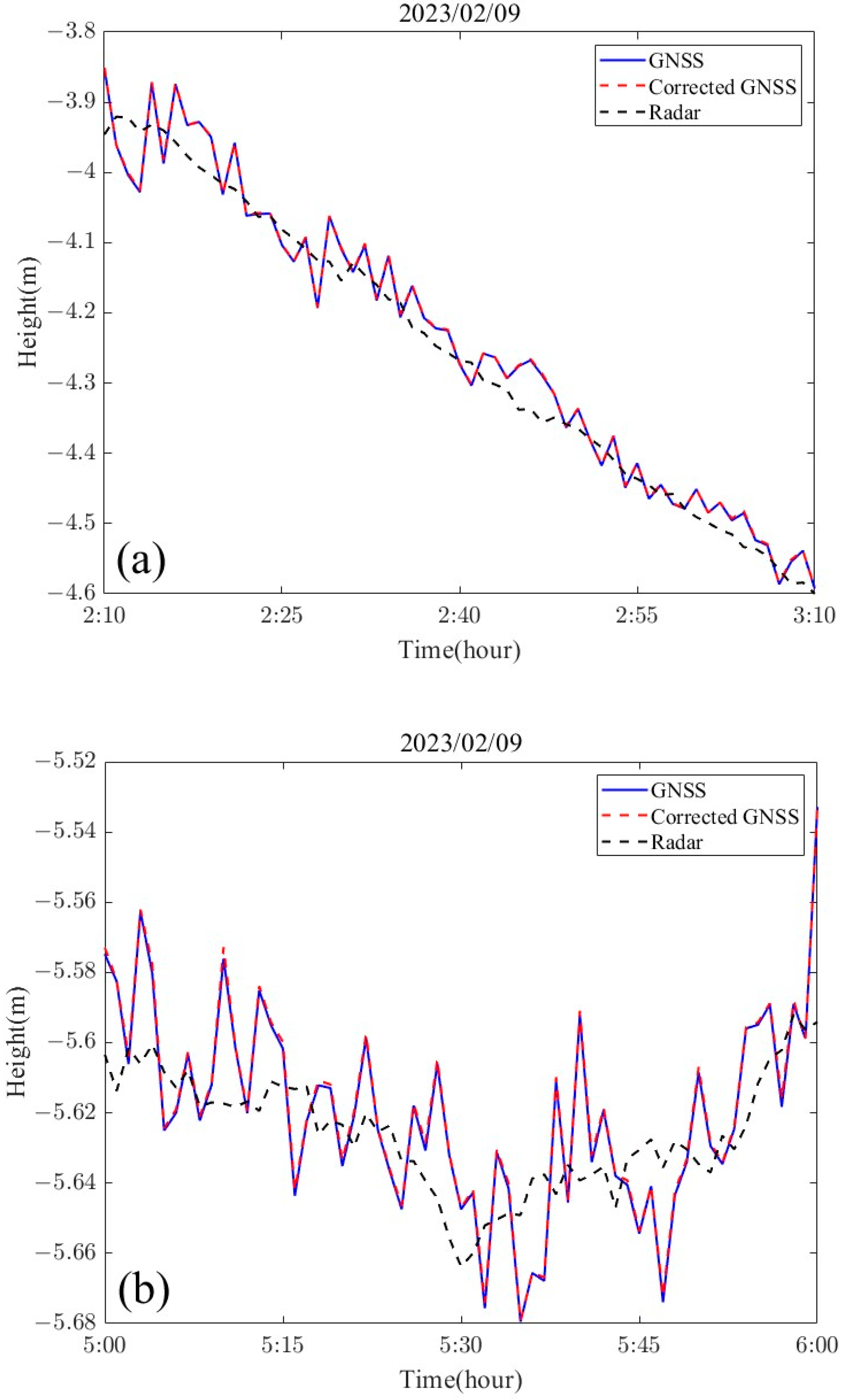

3.4. GNSS Attitude Correction Effect

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The PPK positional calculation was performed on the center antenna of the buoy (Figure 11), and seven complete high-water and first-water levels were obtained. The comparison with a small surface side-cover radar with simultaneous observations yielded a tidal measurement accuracy of about 1 cm (RMSE of 1.12 cm) for the GNSS buoy, which is similar to that obtained from previous deployments of similarly structured GNSS buoys [34], and the remaining measurement error of 1 cm was related to the performance of the GNSS technology and receiver hardware.

- (2)

- The data from the four antennas mounted on the GNSS buoy were processed to obtain the attitude time series of the buoy (Figure 8), and it was found that the magnitude of the change in the attitude angle in the roll and pitch directions in the sea of the GNSS buoy maintained a high degree of consistency, which also verified the previous conclusions of the attitude measurements using the GNSS/INS method [21]. From the results of the attitude solution, the normal high attitude correction for the instantaneous sea surface height on our designed buoy was within 1 cm (Figure 12), while a small amount of correction exceeding 1 cm existed, but these higher corrections were not based on the attitude angle corrected from the normal solution, but were due to the unfixed ambiguity in the dynamic baseline solution process leading to the error in the attitude angle solution [35,36].

- (3)

- After correcting the tidal data of the GNSS buoy using the attitude angle measured by the multi-antenna GNSS, the tidal measurement accuracy was only improved by 0.3 mm compared to the pre-correction values, and similar problems have been encountered by scholars in previous studies [37], which occurred for two reasons: first, because the wobble angle of the buoy itself is not large (−10°~10°), and the second is that the distance of the main antenna of the GNSS buoy from the center of the buoy was very short (0.61 m), which, under the combined influence of these two factors, leads to a small amount of attitude correction for the GNSS buoy, which was not prominent in the tidal extraction process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breslyn, W.; McGinnis, J.R.; McDonald, R.C.; Hestness, E. Developing a Learning Progression for Sea Level Rise, a Major Impact of Climate Change. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2016, 53, 1471–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebisi, N.; Balogun, A.-L.; Min, T.H.; Tella, A. Advances in Estimating Sea Level Rise: A Review of Tide Gauge, Satellite Altimetry and Spatial Data Science Approaches. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 208, 105632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollini, P.; Benveniste, J.; Birol, F.; Fernandes, M.J.; Obligis, E.; Passaro, M.; Strub, P.T.; Valladeau, G.; Vignudelli, S.; Wilkin, J. Satellite Altimetry in Coastal Regions. In Satellite Altimetry Over Oceans and Land Surfaces; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-15177-9. [Google Scholar]

- Vignudelli, S.; Birol, F.; Benveniste, J.; Fu, L.-L.; Picot, N.; Raynal, M.; Roinard, H. Satellite Altimetry Measurements of Sea Level in the Coastal Zone. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 1319–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Terada, Y.; Tadokoro, K.; Futamura, A. Developments of GNSS Buoy for a Synthetic Geohazard Monitoring System. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2022, 98, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsushima, H.; Ohta, Y. Review on Near-Field Tsunami Forecasting from Offshore Tsunami Data and Onshore GNSS Data for Tsunami Early Warning. J. Disaster Res. 2014, 9, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, P.J.; Bird, C.O.; Sinclair, A.; Plater, A.J. A Low-Cost GNSS Buoy Platform for Measuring Coastal Sea Levels. Ocean Eng. 2020, 203, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Y.; Xu, K.; Shen, H.; Liu, Y.-L.; Liu, H.-G. Sea Surface Height and Significant Wave Height Calibration Methodology by a GNSS Buoy Campaign for HY-2A Altimeter. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 5252–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.; Coleman, R.; Handsworth, R. Coastal Tide Gauge Calibration: A Case Study at Macquarie Island Using GPS Buoy Techniques. J. Coast. Res. 2008, 24, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandi, P.; Philipps, S.; Pignot, V.; Picot, N. SARAL/AltiKa Global Statistical Assessment and Cross-Calibration with Jason-2. Mar. Geod. 2015, 38, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.; Coleman, R.; White, N.; Church, J.; Govind, R. Absolute Calibration of TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason-1 Using GPS Buoys in Bass Strait, Australia Special Issue: Jason-1 Calibration/Validation. Mar. Geod. 2003, 26, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, H.; Hung, N.G.; Thoss, H.; Schöne, T. GPS Buoys for Stage Monitoring of Large Rivers. J. Hydrol. 2012, 412–413, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, R.; Nagai, M.; Blanco, A. Lake Water Level Variability Determination from SAR Backscatter of Discrete Objects, GNSS Levelling and Satellite Altimetry. Surv. Rev. 2022, 54, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.O.; Dickhudt, P.; Thomson, J.; de Paolo, T.; Otero, M.; Merrifield, S.; Terrill, E.; Schonau, M.; Braasch, L.; Paluszkiewicz, T.; et al. Performance of Moored GPS Wave Buoys. Coast. Eng. J. 2024, 66, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Zhu, J.; Chen, C.; Zhou, W.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Guo, K. Obtaining Accurate Measurements of the Sea Surface Height from a GPS Buoy. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2023, 42, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. Tsunami-Wave Parameter Estimation Using GNSS-Based Sea Surface Height Measurement. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 2603–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Nan, Y. Tide Variation Monitoring Based Improved GNSS-MR by Empirical Mode Decomposition. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 63, 3333–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskaliyev, A.; Patel, S.H.; Sobh, T.M.; Ibrayev, A. GNSS-Based Attitude Determination Techniques—A Comprehensive Literature Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 24873–24886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Position Loci-Based In-Motion Initial Alignment Method for Low-Cost Attitude and Heading Reference System. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 7500618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Watson, C.; Legresy, B.; King, M.A.; Beardsley, J.; Deane, A. GNSS/INS-Equipped Buoys for Altimetry Validation: Lessons Learnt and New Directions from the Bass Strait Validation Facility. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, A.A.; Jazireeyan, I.; Abdi, N.; Rezvani, M.-H. Evaluation of SARAL/AltiKa Performance Using GNSS/IMU Equipped Buoy in Sajafi, Imam Hassan and Kangan Ports. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 61, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stateczny, A.; Specht, C.; Specht, M.; Brčić, D.; Jugović, A.; Widźgowski, S.; Wiśniewska, M.; Lewicka, O. Study on the Positioning Accuracy of GNSS/INS Systems Supported by DGPS and RTK Receivers for Hydrographic Surveys. Energies 2021, 14, 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Watson, C.; Beardsley, J.; Legresy, B.; King, M.A. Development of a GNSS/INS Buoy Array in Preparation for SWOT Validation in Bass Strait. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1093391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, F. An Adaptive Method of Attitude and Position Estimation during GPS Outages. Measurement 2022, 199, 111474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.M.; Xiang, W.; Li, X. Position and Velocity Estimations of Mobile Device Incorporate GNSS. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 31141–31147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, H.; Zou, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, F. A Novel GNSS Attitude Determination Method Based on Primary Baseline Switching for A Multi-Antenna Platform. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Guo, F. Sea Surface Height Estimation with Multi-GNSS and Wavelet De-Noising. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, M.; Guo, B.; Ren, J.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, A. Sea Surface Height Measurements Using a Low-Cost GNSS Buoy with Multiple GNSS Receivers. Ocean Eng. 2023, 277, 114362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, M.; Zhang, A.; Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Li, M. Evaluation of Real-Time PPP-Based Tide Measurement Using IGS Real-Time Service. Sensors 2020, 20, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruczynski, L.R.; Li, P.C.; Evans, A.G.; Hermann, B.R. Using GPS to Determine Vehicle Attitude. In Proceedings of the International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GPS 1988), Colorado Spring, CO, USA, 19–23 September 1988; pp. 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Sui, L.; Wang, B.; Dai, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zeng, T. The Research on Nonlinear Attitude Determination Method of GNSS Multi-Antenna Attitude Measurement. In Proceedings of the China Satellite Navigation Conference (CSNC) 2017 Proceedings: Volume I; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Shu, Y.; Niu, X.; Liu, J.; Yao, W.; Chen, Q. High-Rate Multi-GNSS Attitude Determination: Experiments, Comparisons with Inertial Measurement Units and Applications of GNSS Rotational Seismology to the 2011 Tohoku Mw9.0 Earthquake. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2019, 30, 024003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, A.A.; Rezvani, M.-H. Improved Vessel Squat Modeling for Hydrographic and Navigation Applications Using Kinematic GNSS Positioning. GPS Solut. 2014, 18, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, X. Retrieving Wave Parameters from GNSS Buoy Measurements Using the PPP Mode. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, L.; Li, L.; Jia, C. Integrity Monitoring of High-Accuracy GNSS-Based Attitude Determination. GPS Solut. 2018, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dong, D.; Chen, W.; Cai, M.; Peng, Y.; Yu, C.; Wu, J. High-Accuracy Attitude Determination Using Single-Difference Observables Based on Multi-Antenna GNSS Receiver with a Common Clock. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Huang, C.-J.; Doong, D.-J.; Kao, C.C. Performance of the GNSS Buoy for Monitoring Tides and Ocean Waves in Coastal Areas. J. Coast. Ocean Eng. 2017, 17, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Parameter Indicators |

|---|---|

| weight | 113.5 kg |

| Height | 946 mm |

| Main radius | 250 mm |

| Max buoyancy | 1747.096 N |

| Max load | 55 kg |

| Depth of entry at full load | 400 mm |

| Volume of the main body of the buoy | 560 mm × 250 mm × 250 mm |

| Calibration Position | Calibrated Elevation |

|---|---|

| Total station control point elevation | 0 m |

| Total station instrument elevation | 1.365 m |

| GNSS base station height (antenna phase center) | 1.5921 m |

| Sea surface altimetry radar antenna height | 0.151 m |

| Total draft of the buoy | 0.799 m |

| Baseline | Baseline Length | Ambiguity Fixed Rate | Standard Deviation of Baseline Length | Max Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANT02–ANT01 | 0.9668 m | 96.5% | 0.0042 m | 0.3305 m |

| ANT02–ANT04 | 0.9698 m | 97.3% | 0.0031 m | 0.2705 m |

| ANT03–ANT04 | 0.9682 m | 97.9% | 0.0028 m | 0.2518 m |

| Method | MAD | SD | RMSE | Max Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNSS | 0.0189 m | 0.0251 m | 0.0254 m | 0.1546 m |

| Corrected GNSS | 0.0188 m | 0.0250 m | 0.0252 m | 0.1518 m |

| GNSS (900 s) | 0.0086 m | 0.0111 m | 0.0115 m | 0.0479 m |

| Corrected GNSS (900 s) | 0.0082 m | 0.0105 m | 0.0112 m | 0.0477 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, X.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhao, R.; Shao, H. Sea Surface Height Measurements Based on Multi-Antenna GNSS Buoys. Sensors 2024, 24, 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113451

Xue X, Yang J, Zhao Q, Wang S, Zhao R, Shao H. Sea Surface Height Measurements Based on Multi-Antenna GNSS Buoys. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113451

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Xiaoming, Jichao Yang, Qing Zhao, Shengli Wang, Ranshuo Zhao, and Hulin Shao. 2024. "Sea Surface Height Measurements Based on Multi-Antenna GNSS Buoys" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113451

APA StyleXue, X., Yang, J., Zhao, Q., Wang, S., Zhao, R., & Shao, H. (2024). Sea Surface Height Measurements Based on Multi-Antenna GNSS Buoys. Sensors, 24(11), 3451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113451