A Flexible Double-Sided Curvature Sensor Array for Use in Soft Robotics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Piezoresistive Sensor Concept and Design

2.2. Sensor Strip Fabrication Method

2.3. Sensor Evaluation Circuitry

2.4. Shape Memory Alloy Actuated Robotic Fingers

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single Sensor Strip Characterization

3.2. Smart Finger Shape Feedback Sensor

3.3. Object Sensing in a Flexible Granular Material Gripper

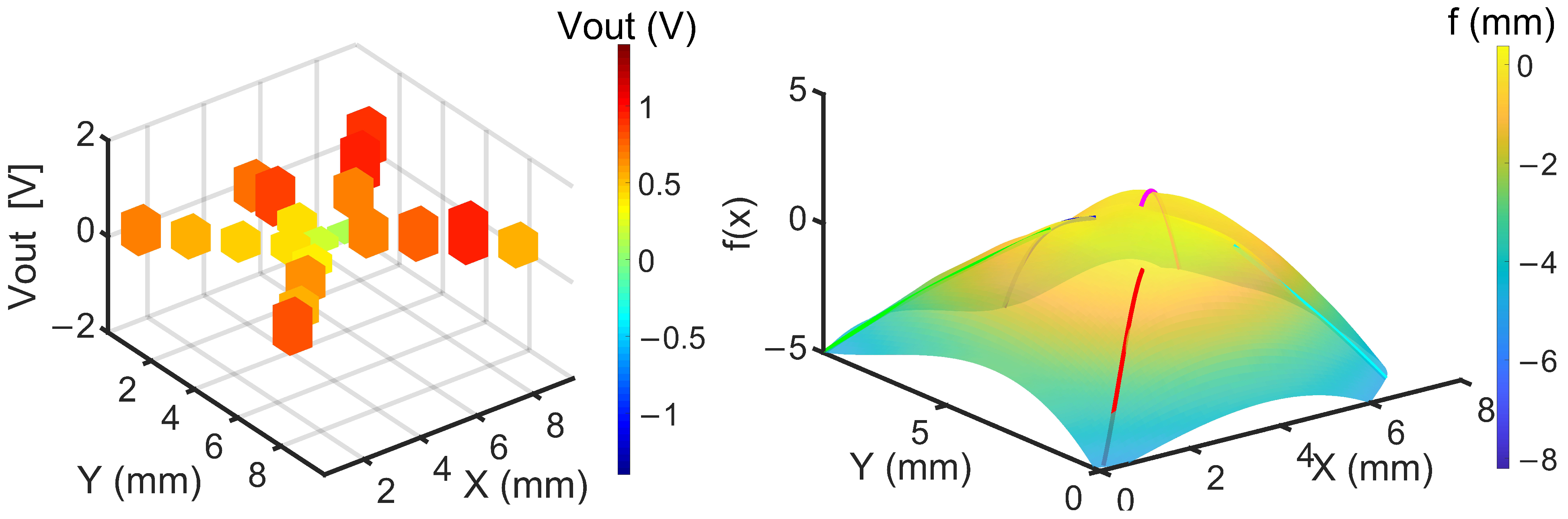

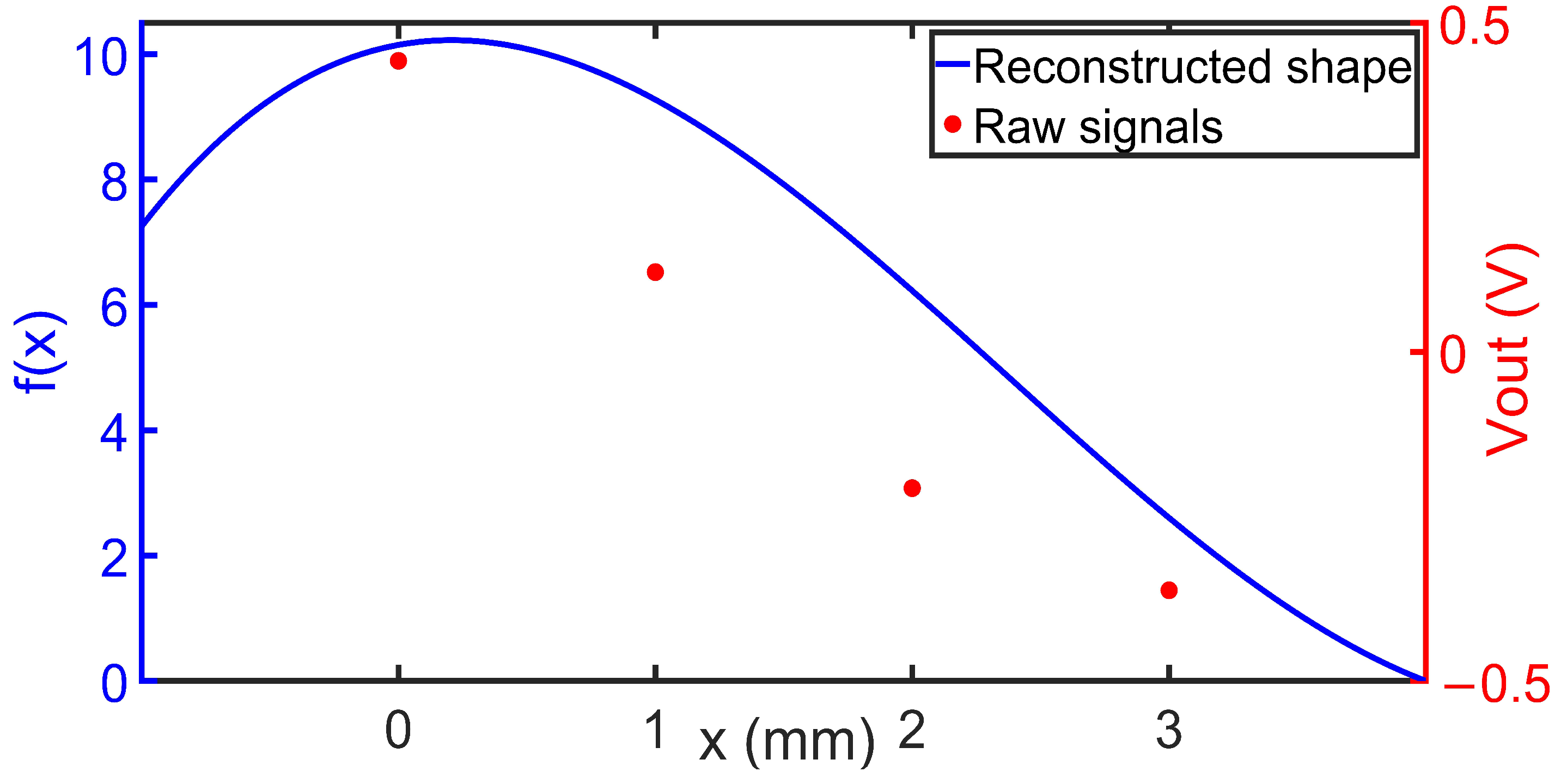

3.4. 3D Mapping of an S-Shaped Surface

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, Y.-G.; Song, J.-H.; Hong, S.; Ahn, S.-H. Piezoelectric strain sensor with high sensitivity and high stretchability based on kirigami design cutting. npj Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xu, Z.; Li, D.; Cui, T.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Ren, T. Recent Advances in Flexible Piezoresistive Arrays: Materials, Design, and Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Fang, L.; Sun, B.; Li, X.; Kang, S.H. Review—Recent Progress in Flexible and Stretchable Piezoresistive Sensors and Their Applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 037561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, A.; Clemens, F. Piezoresistive Elastomer-Based Composite Strain Sensors and Their Applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 1826–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Bok, B.-G.; Ahn, J.-H.; Kim, M.-S. Recent Advances in Tactile Sensing Technology. Micromachines 2018, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, J.; Knoop, E.; Mutný, M.; Otaduy, M.A.; Bächer, M. MakeSense: Automated Sensor Design for Proprioceptive Soft Robots. Soft Robot. 2020, 7, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.M.; Wang, H.; Kim, B.H.; Lee, K.; Jang, H.; Kwon, K.; Han, M.; Crawford, K.E.; Li, H.; Lee, Y.; et al. Multimodal Sensing with a Three-Dimensional Piezoresistive Structure. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 10972–10979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souri, H.; Banerjee, H.; Jusufi, A.; Radacsi, N.; Stokes, A.A.; Park, I.; Sitti, M.; Amjadi, M. Wearable and Stretchable Strain Sensors: Materials, Sensing Mechanisms, and Applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 2000039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Xia, Z.; Cai, K. A review of electronic skin: Soft electronics and sensors for human health. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuruthel, T.G.; Shih, B.; Laschi, C.; Tolley, M.T. Soft robot perception using embedded soft sensors and recurrent neural networks. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaav1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, C.; Su, J.; Tan, J.M.R.; He, K.; Chen, X.; Magdassi, S. Sensing in Soft Robotics. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15277–15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Totaro, M.; Beccai, L. Toward Perceptive Soft Robots: Progress and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polygerinos, P.; Correll, N.; Morin, S.A.; Mosadegh, B.; Onal, C.D.; Petersen, K.; Cianchetti, M.; Tolley, M.T.; Shepherd, R.F. Soft Robotics: Review of Fluid-Driven Intrinsically Soft Devices; Manufacturing, Sensing, Control, and Applications in Human-Robot Interaction. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2017, 19, 1700016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, M.; Ossmer, H.; Gueltig, M.; Megnin, C. SMA Foils for MEMS: From Material Properties to the Engineering of Microdevices. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2018, 4, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, R.; Galloway, T.L. Strain Measurement in a Shape Memory Alloy with Strain Gauges. Strain 2005, 41, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäder, T.; Heusinger, J.V.; Senf, B.; Zoch, M.; Winkler, A.; Drossel, W.-G. Calibration of piezoresistive shape-memory alloy strain sensors. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2022, 33, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, E.; Dietzel, A. Skin attachable flexible sensor array for respiratory monitoring. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2016, 250, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, E.; Dietzel, A. Stretchable sensor array for respiratory monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2017 19th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 18–22 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 2227–2230. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, E.; Dietzel, A.; Tutsch, R. Stretchable Sensor Array Patch for Respiratory Monitoring; Schriftenreihe Mikrotechnik; Shaker Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, J.; Frilund, P.; Vuorinen, I.; Kuosmanen, P.; Kiviluoma, P. Granular jamming based robotic gripper for heavy objects. Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci. 2019, 68, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benarrait, R.; Ullah-Khan, M.; Terrien, J.; Al Hajjar, H.; Lamarque, F.; Dietzel, A. A Flexible Double-Sided Curvature Sensor Array for Use in Soft Robotics. Sensors 2024, 24, 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113475

Benarrait R, Ullah-Khan M, Terrien J, Al Hajjar H, Lamarque F, Dietzel A. A Flexible Double-Sided Curvature Sensor Array for Use in Soft Robotics. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113475

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenarrait, Racha, Muneeb Ullah-Khan, Jérémy Terrien, Hani Al Hajjar, Frédéric Lamarque, and Andreas Dietzel. 2024. "A Flexible Double-Sided Curvature Sensor Array for Use in Soft Robotics" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113475

APA StyleBenarrait, R., Ullah-Khan, M., Terrien, J., Al Hajjar, H., Lamarque, F., & Dietzel, A. (2024). A Flexible Double-Sided Curvature Sensor Array for Use in Soft Robotics. Sensors, 24(11), 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113475