Design of Wearable Textile Electrodes for the Monitorization of Patients with Heart Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Establishment of the User Needs

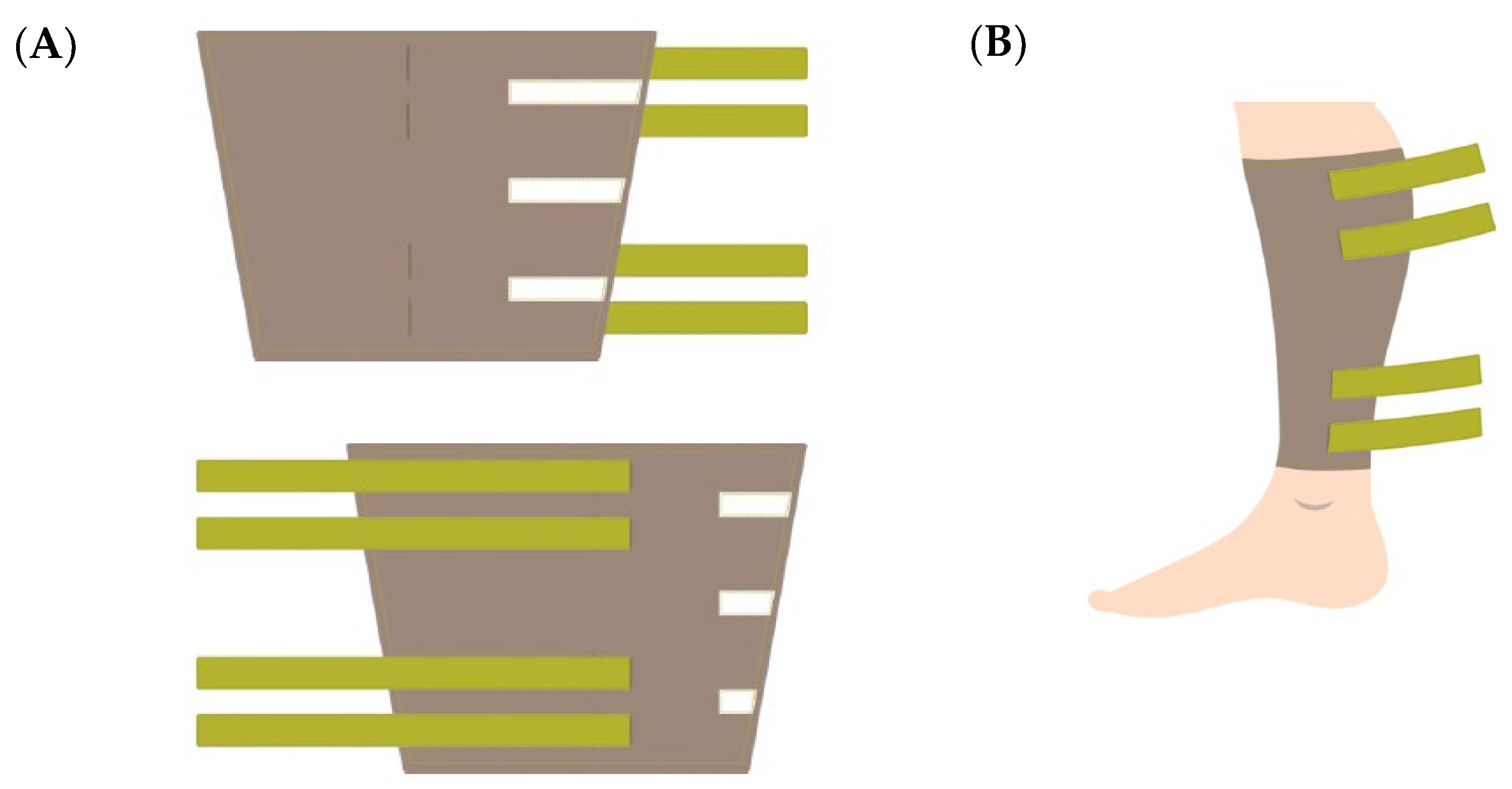

2.2. Design of the Wearable Electrodes

2.3. Implementation of the Wearable Electrodes

2.4. Impedance Spectroscopy Measurement System

2.5. Study Protocol

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, S.; Gimenez, L.; Pérez, P.; Martín, D.; Olmo, A.; Huertas, G.; Medrano, F.J.; Yúfera, A. From Bioimpedance to Volume Estimation: A Model for Edema Calculus in Human Legs. Electronics 2023, 12, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.; Tong, W. Measuring impedance in congestive heart failure: Current options and clinical applications. Am. Heart J. 2009, 157, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzesinski, P.; Sobotnicki, A.; Gacek, A.; Siebert, J.; Walczak, A.; Murawski, P.; Gielerak, G. Noninvasive Bioimpedance Methods From the Viewpoint of Remote Monitoring in Heart Failure. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e25937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puertas, M.; Giménez, L.; Pérez, A.; Scagliusi, S.F.; Pérez, P.; Olmo, A.; Huertas, G.; Medrano, F.J.; Yúfera, A. Modeling Edema Evolution with Electrical Bioimpedance: Application to Heart Fail Patients. In Proceedings of the 2021 XXXVI Conference on Design of Circuits and Integrated Systems (DCIS), Vila do Conde, Portugal, 24–26 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Giaever, I.; Keese, C. A morphological biosensor for mammalian cells. Nature 1993, 366, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkholder, D.A. Cell-Based Biosensors Using Microelectrodes. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, A.; Barroso, P.; Olmo, A.; Yufera, A. Bioimpedance Sensing of Implanted Stent Occlusions: Smart Stent. Biosensors 2022, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaw, R.L.; Terrones, B.S.; Impedimed Ltd. Evaluating Impedance Measurements. Patent WO2020061619A1, 2 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cuba, I.G.L. Monitoring Heart Failure Using Noninvasive Measurements of Thoracic Impedance. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Du, K.; Lin, R.; Yin, L.; Ho, J.S.; Wang, J.; Lim, C.T. Electronic textiles for energy, sensing, and communication. iScience 2022, 25, 104174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Electronic fibers and textiles: Recent progress and perspective. iScience 2021, 24, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, F.J.; Castillo, E.; Rivadeneyra, A.; Toral-López, A.; Becherer, M.; Ruiz, F.G.; Rodríguez, N.; Morales, D.P. Inexpensive and flexible nanographene-based electrodes for ubiquitous electrocardiogram monitoring. Npj Flex. Electron. 2019, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckdashel, R.R.; Khadse, N.; Park, J.H. Smart E-Textiles: Overview of Components and Outlook. Sensors 2022, 22, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassanos, P. Bioimpedance Sensors: A Tutorial. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 22190–22219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieldex® Technik-tex P130 + B—Metallized Technical Textiles. Available online: https://www.shieldex.de/products/shieldex-technik-tex-p130-b/ (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Medrano, J.; Yúfera, A. Real-Time Monitoring Prognostic Value of Volume with BI Test in Patients with Acute HF; (HEART-FAIL VOLUM); DTS19/00134 and DTS19/00137; Instituto Carlos III: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- SFB7 Impedimed. Available online: https://www.impedimed.com/products/research-devices/sfb7/ (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Metshein, M. 1—Coupling and electrodes. In Bioimpedance and Spectroscopy; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Grimnes, S.; Martinsen, G. Chapter 7—electrodes. In Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity Basics; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 179–254. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez, M.J.; Scagliusi, S.J.F.; Giménez-Miranda, L.; Pérez, P.; Medrano, F.J.; Olmo Fernández, A. Design of Wearable Textile Electrodes for the Monitorization of Patients with Heart Failure. Sensors 2024, 24, 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113637

Sánchez MJ, Scagliusi SJF, Giménez-Miranda L, Pérez P, Medrano FJ, Olmo Fernández A. Design of Wearable Textile Electrodes for the Monitorization of Patients with Heart Failure. Sensors. 2024; 24(11):3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113637

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez, María Jesús, Santiago J. Fernández Scagliusi, Luis Giménez-Miranda, Pablo Pérez, Francisco Javier Medrano, and Alberto Olmo Fernández. 2024. "Design of Wearable Textile Electrodes for the Monitorization of Patients with Heart Failure" Sensors 24, no. 11: 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113637

APA StyleSánchez, M. J., Scagliusi, S. J. F., Giménez-Miranda, L., Pérez, P., Medrano, F. J., & Olmo Fernández, A. (2024). Design of Wearable Textile Electrodes for the Monitorization of Patients with Heart Failure. Sensors, 24(11), 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24113637