Understanding the Design and Sensory Behaviour of Graphene-Impregnated Textile-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

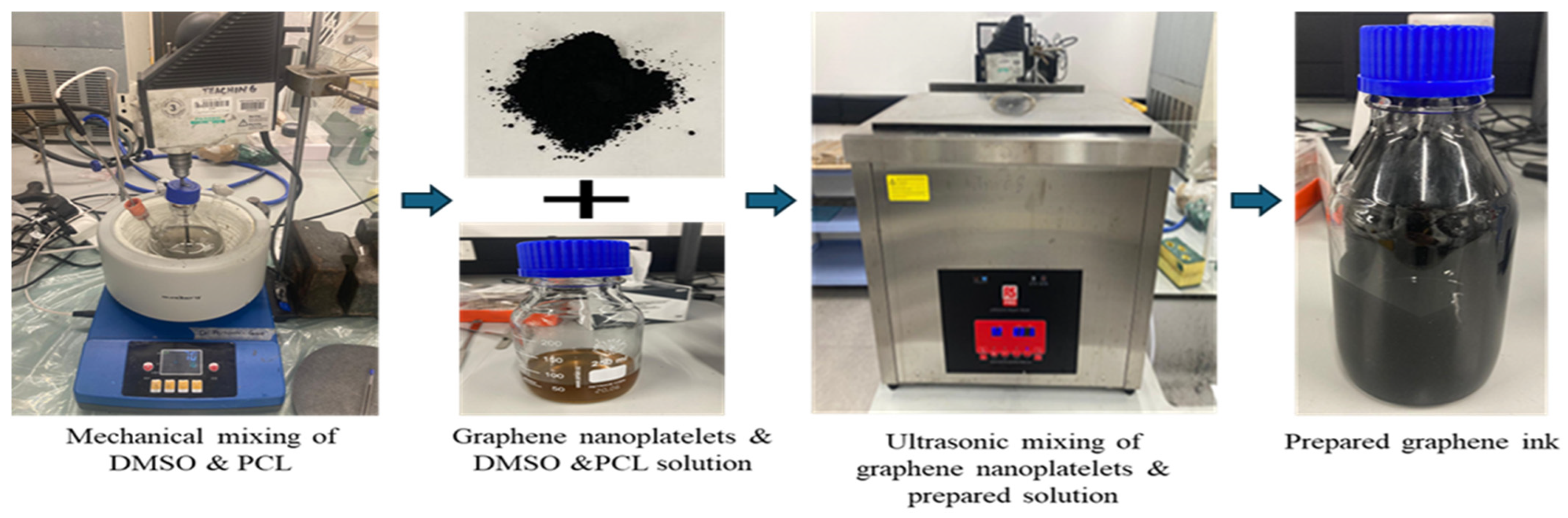

2.2. Preparation of Graphene Ink

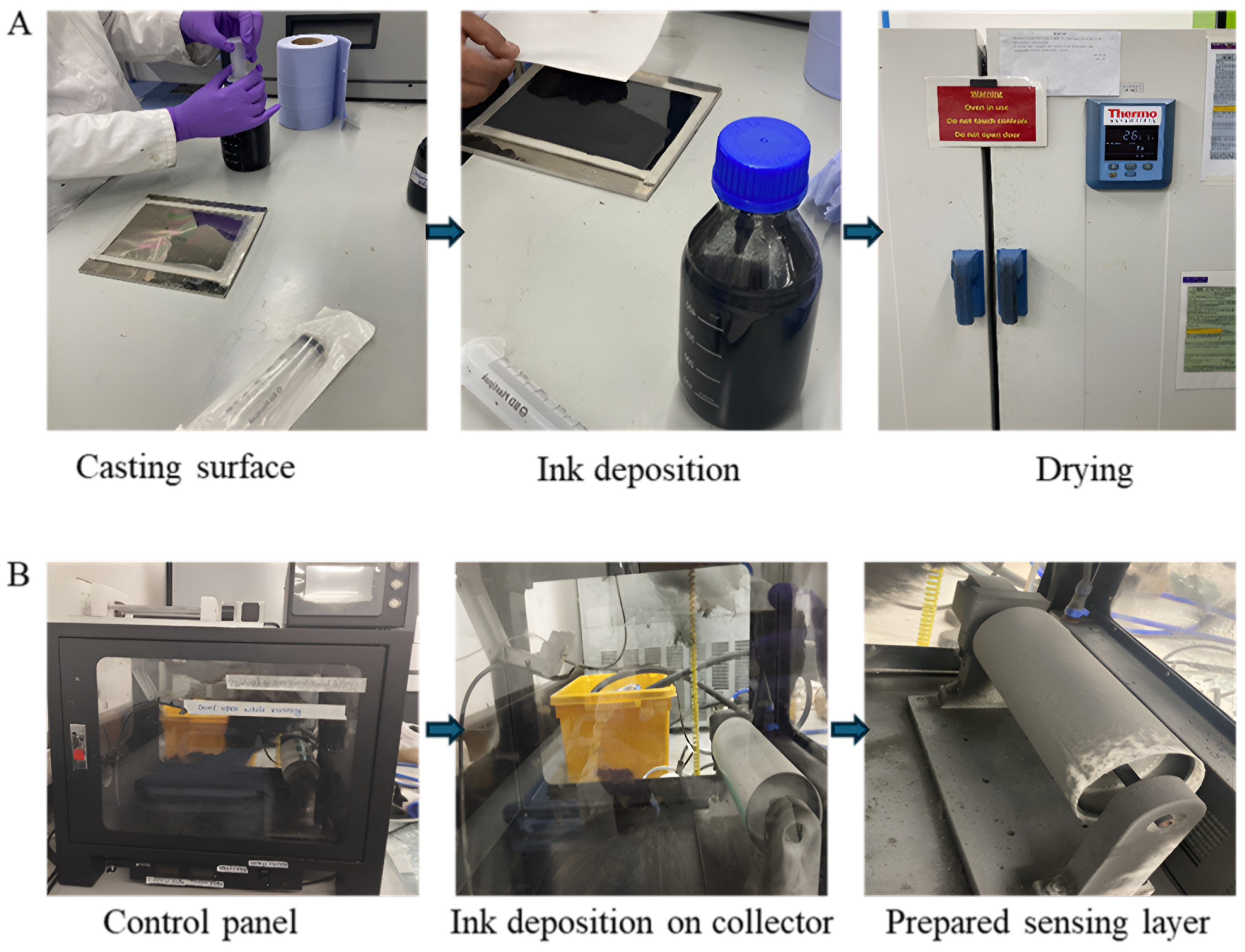

2.3. Preparation of Graphene-Impregnated Piezoresistive Sensing Layer

2.4. Characterisation

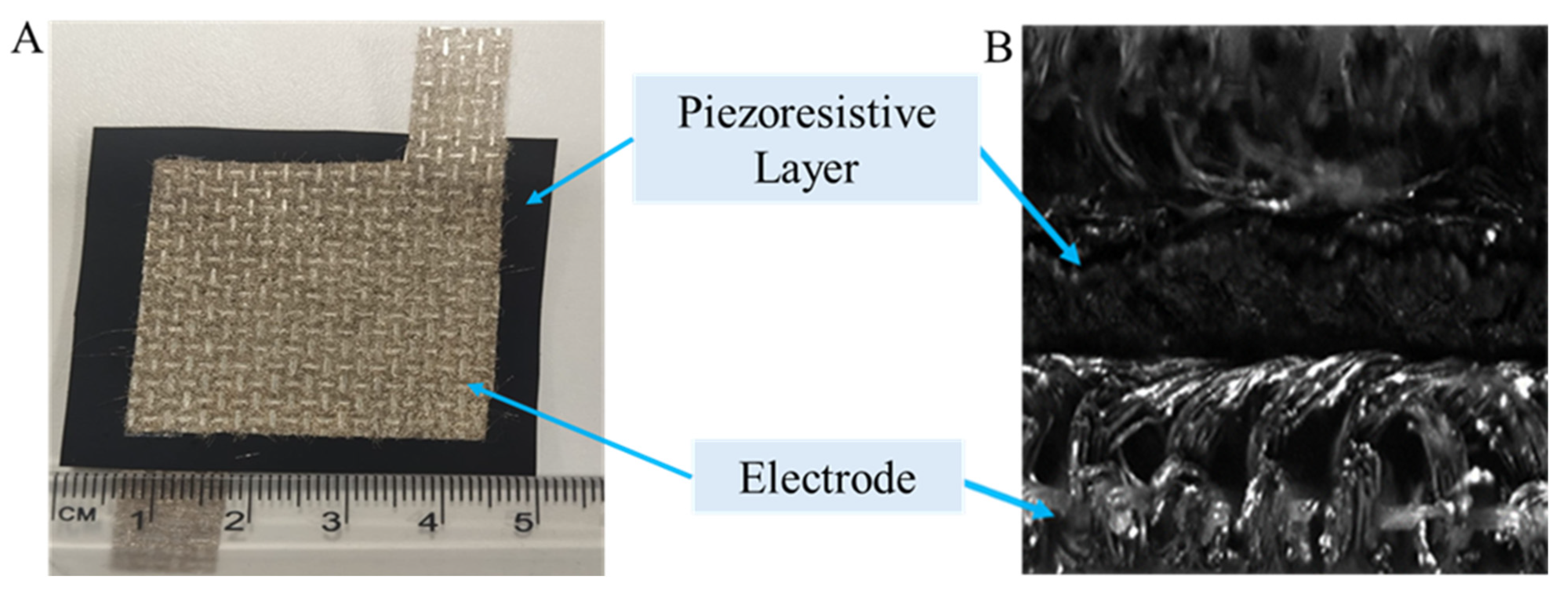

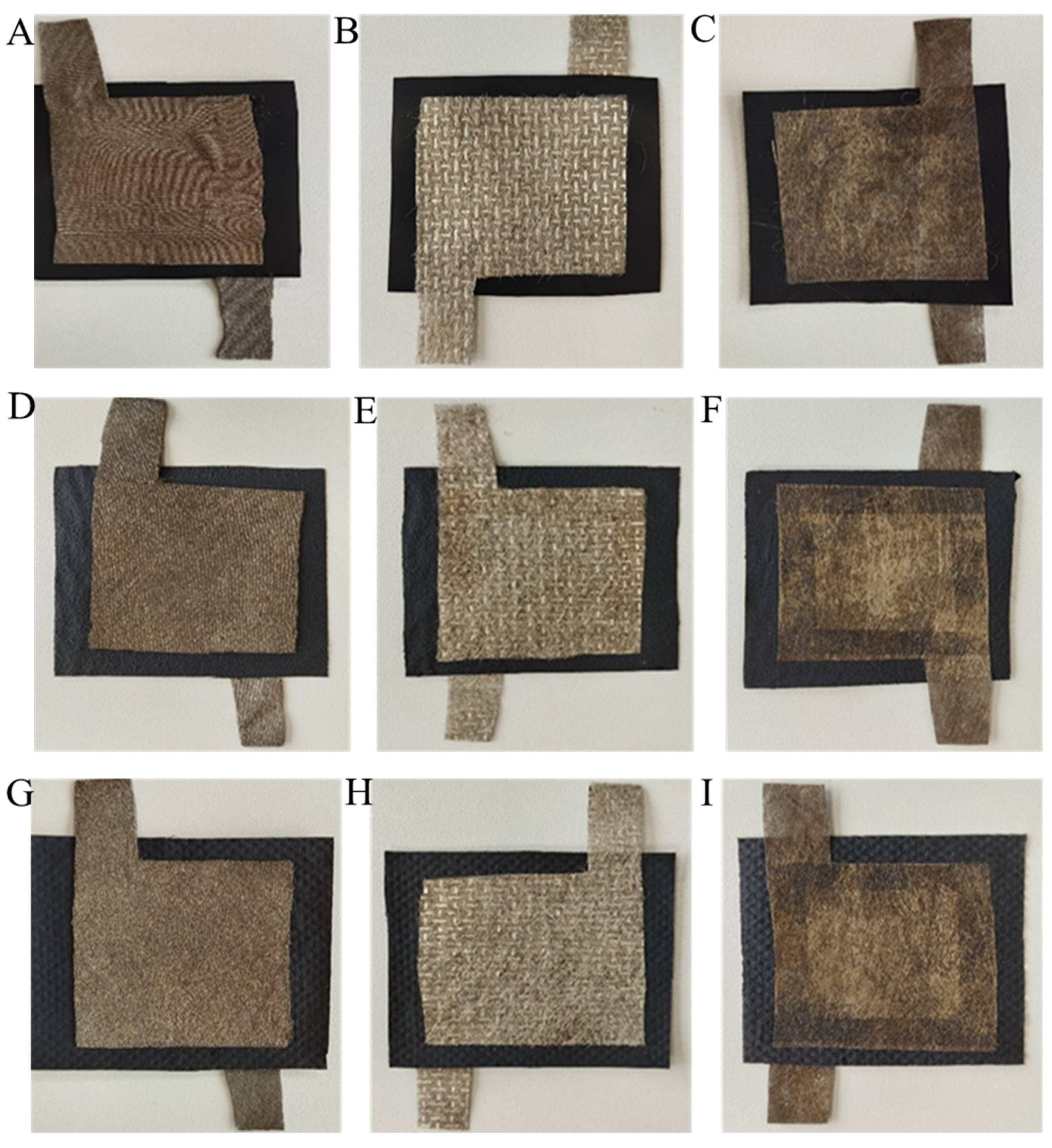

2.5. Fabrication of the Piezoresistive Sensing Layers with Electrodes

2.6. Measurement of the Resistance of the Sensors

2.6.1. Initial Resistance Measurement of the Sensors

2.6.2. Resistance Measurement by Half-Bridge Circuit

2.7. Electromechanical Quasi-Static Compression Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy Analysis

3.2. Morphological Investigation (SEM)

3.3. The Initial Resistance of the Piezoresistive Sensors

3.4. The Electromechanical Characterisation of Different Sensors

3.4.1. The Electrical Resistance of the Prepared Sensors in Dynamic Conditions

3.4.2. Changes in Sheet Resistance Due to Applied Pressure (0 to 50 KPa) on Graphene-Impregnated Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors over the Half-Cycle Period

3.4.3. Analysis of the Sensitivity of Graphene-Impregnated Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors over a Cycle Period

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. Textile-Based Flexible Pressure Sensors: A Review. Polym. Rev. 2022, 62, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Ip, W.H.; Lin, X.; Yousefi, N.; Yeung, K.K.; Li, Z.; Kim, J.-K. Transparent Conductive Films Consisting of Ultralarge Graphene Sheets Produced by Langmuir–Blodgett Assembly. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6039–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; He, Y.; Liang, Y.; Tang, J.; Yang, Y.; Song, H.M.; Zrínyi, M.; Chen, Y.M. Sensitive piezoresistive pressure sensor based on micropyramid patterned tough hydrogel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 615, 156328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Liu, K.; Xu, J.; Ye, M.; Yang, T.; Qi, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H. High-performance multifunctional piezoresistive/piezoelectric pressure sensor with thermochromic function for wearable monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Guo, Y.; Zuo, S.; Shi, F.; Jiang, J.; Chu, J. A bioinspired porous-designed hydrogel@polyurethane sponge piezoresistive sensor for human–machine interfacing. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 19155–19164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chao, M.; Wan, P.; Zhang, L. A wearable breathable pressure sensor from metal-organic framework derived nanocomposites for highly sensitive broad-range healthcare monitoring. Nano Energy 2020, 70, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.-Y.; Peng, S.-Q.; Wu, L.-X.; Sun, Q. 3D-printed stretchable sensor based on double network PHI/PEDOT:PSS hydrogel annealed with cosolvent of H2O and DMSO. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 14405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.; Ryu, S.; Woo, Y.S. Role of graphene towards long-term stability of flexible heaters made of graphene-coated silver nanowire networks under repeated deformation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Carey, T.; Chen, K.; Yin, Y.; Torrisi, F. Environmentally-friendly conductive cotton fabric as flexible strain sensor based on hot press reduced graphene oxide. Carbon 2017, 111, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lee, J.; Shen, X.; Chen, X.; Kim, J.-K. Graphene-based wearable piezoresistive physical sensors. Mater. Today 2020, 36, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Dai, W.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, L.; Poon, C.C.Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, N. Flexible Piezoresistive Sensor Patch Enabling Ultralow Power Cuffless Blood Pressure Measurement. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ali, S.; Wijekoon, J.H.B.; Gong, H.; Fernando, A. A wearable piezoresistive sensor for capturing cardiorespiratory signals. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2018, 282, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tian, M.; Sun, X.; Pan, N.; Chen, F.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S. Highly sensitive wearable 3D piezoresistive pressure sensors based on graphene coated isotropic nonwoven substrate. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 117, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Su, C.; Bi, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Shao, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, N. Ti(3)C(2)T(x)@nonwoven Fabric Composite: Promising MXene-Coated Fabric for Wearable Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 9632–9643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, P. Preparation and characterisation of flexible pressure sensor based on silver nanowires/nonwoven fabric. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 2523–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Mirihanage, W.; Potluri, P.; Fernando, A. Isophorone-Based Quaternary Compound Modified Graphene for Machine Washable Nonwoven Piezoresistive Sensors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2202020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Zhu, F.; Ahmed, A.; Khoso, N.A.; Deb, H.; Yuchao, L.; Islam, Z.; Sun, H.; Yu, B. Functionalisation of polypropylene nonwoven fabrics using cold plasma (O2) for developing graphene-based wearable sensors. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2019, 300, 111637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, X.; Wang, P.; Xu, Y. Fabrication of a Conductive Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-Coated Polyester Nonwoven Fabric and Its Application in Flexible Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 3177–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrmann, A.; Heimlich, F.; Brücken, A.; Weber, M.; Haug, R. Suitability of knitted fabrics as elongation sensors subject to structure, stitch dimension and elongation direction. Text. Res. J. 2014, 84, 2006–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, R. Fiber/Yarn and Textile-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2025, 7, 34–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.K.; Chatterjee, A. Graphene-coated nylon nonwoven for pressure sensing application. J. Text. Inst. 2024, 115, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode | Thickness (mm) | Areal Density (g/m2) | Electrical Resistance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knitted fabric | 0.38 | 140 | <100 Ω/Sq. | HITEK LTD |

| Spunbonded Nonwoven | 0.1 | 60 | <100 Ω/ Sq. | HITEK LTD |

| Powder-bonded Nonwoven | 0.15 | 70 | <100 Ω/ Sq. | HITEK LTD |

| Solutions | Flow Rate (ml//hr.) | Voltage (KV) | Needle Gauge (Number of Needles/Inch) | Working Distance (cm) | Collector Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethane Diol | 5 | 25 | 18 | 20 | 250 |

| Graphene Ink | 3 | 25 | 18 | 20 | 250 |

| Piezoresistive Sensing Layer | Thickness (mm) | Areal Density (g/m2) | Dimension (Length × Width) | Graphene Content (g) | Fibre/Polymer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop casted | 0.38 | 305 | 50 mm × 50 mm | 0.146 | Polycaprolactone |

| Electro-spun | 0.60 | 196 | 50 mm × 50 mm | 0.094 | Polycaprolactone |

| Electro-sprayed | 0.20 | 48 | 50 mm × 50 mm | 0.022 | Polypropylene /Polyester |

| Initial Resistance | Source of Variation | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop casted sensors | Between Groups | 0.035 | 2 | 0.0178 | 7.778504 | 0.006 |

| Within Groups | 0.027 | 12 | 0.002 | |||

| Total | 0.063 | 14 | ||||

| Electro-spun sensors | Between Groups | 3.835 | 2 | 1.917 | 16.328 | 0.001 |

| Within Groups | 1.409 | 12 | 0.117 | |||

| Total | 5.244 | 14 | ||||

| Electro-spraying sensors | Between Groups | 33,403.6 | 2 | 16,701.8 | 749.519 | 0 |

| Within Groups | 267.4 | 12 | 22.283 | |||

| Total | 33,671 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmud, M.F.; Ahmed, M.R.; Potluri, P.; Fernando, A. Understanding the Design and Sensory Behaviour of Graphene-Impregnated Textile-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. Sensors 2025, 25, 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25072000

Mahmud MF, Ahmed MR, Potluri P, Fernando A. Understanding the Design and Sensory Behaviour of Graphene-Impregnated Textile-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. Sensors. 2025; 25(7):2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25072000

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmud, Md Faisal, Md Raju Ahmed, Prasad Potluri, and Anura Fernando. 2025. "Understanding the Design and Sensory Behaviour of Graphene-Impregnated Textile-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors" Sensors 25, no. 7: 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25072000

APA StyleMahmud, M. F., Ahmed, M. R., Potluri, P., & Fernando, A. (2025). Understanding the Design and Sensory Behaviour of Graphene-Impregnated Textile-Based Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. Sensors, 25(7), 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25072000