Profile and Content of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Flowers, Roots, and Stalks of Sanguisorba officinalis L. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis and Their In Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antiproliferative Potency

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identification of Polyphenolic Compounds

2.2. Quantification of Polyphenolic Compounds

2.3. Pro-Health Properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Material, Reagents, and Instruments

3.2. Determination of Polyphenols

3.3. Pro-Health Properties

3.3.1. Antiradical Capacity

3.3.2. Reducing Potential

3.3.3. Determination of Enzyme Inhibition Potency

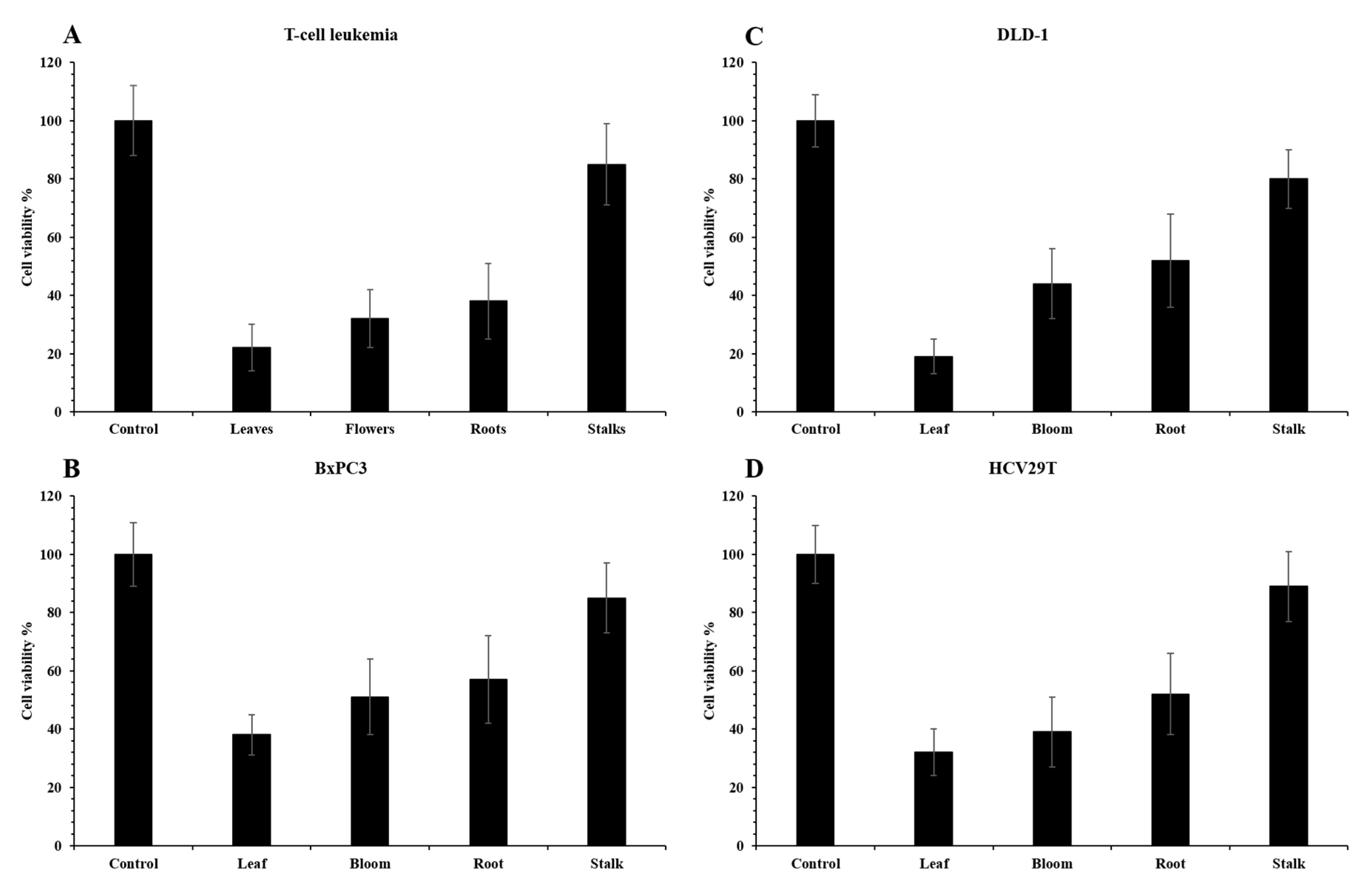

3.3.4. Antiproliferative Potency

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Determination of Cell Viability

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.; Oh, S.; Noh, H.B.; Ji, S.; Lee, S.H.; Koo, J.M.; Choi, C.W.; Jhun, H.P. In vitro antioxidant and anti-propionibacterium acnes activities of cold water, hot water, and methanol extracts, and their respective ethyl acetate fractions, from Sanguisorba officinalis L. Roots. Molecules 2018, 23, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.-L.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.-N.; Wang, Q.-R.; Wan, L.; Jian, S.-P. Characterization of polyphenolic constituents from Sanguisorba officinalis L. and its antibacterial activity. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1487–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkanis, A.C.; Fernandes, A.; Vaz, J.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Georgiou, E.; Ćirić, A.; Sokovic, M.D.; Oludemi, T.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Chemical composition and bioactive properties of Sanguisorba minor Scop. under Mediterranean growing conditions. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Cho, S.O.; Ban, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Ju, H.S.; Koh, S.B.; Song, K.-S.; Seong, Y.H. Neuroprotective effect of Sanguisorbae radix against oxidative stress-induced brain damage: In vitro and in vivo. Boil. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Koyyalamudi, S.R.; Jeong, S.C.; Reddy, N.; Smith, P.T.; Rajendran, A.; Longvah, T. Antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides from the roots of Sanguisorba officinalis. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2012, 51, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Loo, W.T.; Wang, N.; Chow, L.W.; Wang, N.; Han, F.; Zheng, X.; Chen, J.-P. Effect of Sanguisorba officinalis L on breast cancer growth and angiogenesis. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, S79–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, Z.; Peng, J.; Zheng, X.; Nishiura, K.; Ng, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. Extracts of the medicinal herb Sanguisorba officinalis inhibit the entry of human immunodeficiency virus-1. J. Food Drug Anal. 2013, 21, S52–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.H.; Chung, C.B.; Kim, J.G.; Ko, K.I.; Park, S.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Eom, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Hwang, Y.-I.; Kim, K.-H. Anti-Wrinkle Activity of Ziyuglycoside I Isolated from a Sanguisorba officinalis Root Extract and Its Application as a Cosmeceutical Ingredient. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008, 72, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Wojdyło, A.; Cebulak, T.; Hirnle, L.; Siewiński, M. UPLC-PDA-Q/TOF-MS identification of bioactive compounds and on-line UPLC-ABTS assay in Fallopia japonica Houtt and Fallopia sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) leaves and rhizomes grown in Poland. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 245, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yisimayili, Z.; Abdulla, R.; Tian, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Aisa, H.A.; Huang, C. A comprehensive study of pomegranate flowers polyphenols and metabolites in rat biological samples by high-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1604, 460472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot-Hadzik, I.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Granica, S.; Hadzik, J.; Matkowski, A. Phytochemical Diversity in Rhizomes of Three Reynoutria Species and their Antioxidant Activity Correlations Elucidated by LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bunse, M.; Lorenz, P.; Stintzing, F.C.; Kammerer, D.R. Characterization of Secondary Metabolites in Flowers of Sanguisorba officinalis L. by HPLC-DAD-MS n and GC/MS. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, 1900724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentandreu, E.; Cerdán-Calero, M.; Sendra, J.M. Phenolic profile characterization of pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice by high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection coupled to an electrospray ion trap mass analyzer. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 30, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.-Z.; Dong, X.; Guo, M. Phenolic Profiling of Duchesnea indica Combining Macroporous Resin Chromatography (MRC) with HPLC-ESI-MS/MS and ESI-IT-MS. Molecules 2015, 20, 22463–22475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esposito, T.; Celano, R.; Pane, C.; Piccinelli, A.L.; Sansone, F.; Picerno, P.; Zaccardelli, M.; Aquino, R.P.; Mencherini, T. Chestnut (Castanea sativa Miller.) burs extracts and functional compounds: UHPLC-UV-HRMS profiling, antioxidant activity, and inhibitory effects on Phytopathogenic Fungi. Molecules 2019, 24, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, A.; Sousa, A.; Mateus, N.; Cabral, M.; De Freitas, V. Analysis of phenolic compounds in cork from Quercus suber L. by HPLC-DAD/ESI-MS. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mämmelä, P.; Savolainen, H.; Lindroos, L.; Kangas, J.; Vartiainen, T. Analysis of oak tannins by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 891, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, W.; Yokota, T.; Lean, M.E.; Crozier, A. Analysis of ellagitannins and conjugates of ellagic acid and quercetin in raspberry fruits by LC-MSn. Phytochemistry 2003, 64, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, M.N.; Johnston, K.L.; Knight, S.; Kuhnert, N. Hierarchical Scheme for LC-MSnIdentification of Chlorogenic Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2900–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lin, L.-Z.; Chen, P. Study of the mass spectrometric behaviors of anthocyanins in negative ionization mode and its applications for characterization of anthocyanins and non-anthocyanin polyphenols. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 26, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, H.S.; Singh, Z.; Swinny, E. Dynamics of anthocyanin and flavonol profiles in the ‘Crimson Seedless’ grape berry skin during development and ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 117, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rockenbach, I.I.; Jungfer, E.; Ritter, C.; Santiago-Schübel, B.; Thiele, B.; Fett, R.; Galensa, R. Characterization of flavan-3-ols in seeds of grape pomace by CE, HPLC-DAD-MSn and LC-ESI-FTICR-MS. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ito, C.; Oki, T.; Yoshida, T.; Nanba, F.; Yamada, K.; Toda, T. Characterisation of proanthocyanidins from black soybeans: Isolation and characterisation of proanthocyanidin oligomers from black soybean seed coats. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 2507–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad-García, B.; Garmón-Lobato, S.; Berrueta, L.; Gallo, B.; Vicente, F. Practical guidelines for characterization ofO-diglycosyl flavonoid isomers by triple quadrupole MS and their applications for identification of some fruit juices flavonoids. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009, 44, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Tsai, Y.-J.; Tsay, J.-S.; Lin, J.-K. Factors Affecting the Levels of Tea Polyphenols and Caffeine in Tea Leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1864–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, J.; Kucekova, Z.; Humpolíček, P.; Mlček, J.; Saha, P. Polyphenolic Extracts of Edible Flowers Incorporated onto Atelocollagen Matrices and Their Effect on Cell Viability. Molecules 2013, 18, 13435–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Deng, M.; Lv, Z.; Peng, Y. Evaluation of antioxidant activities of extracts from 19 Chinese edible flowers. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elfalleh, W. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of pomegranate peel, seed, leaf and flower. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 4724–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loza-Mejía, M.A.; Salazar, J.R. Sterols and triterpenoids as potential anti-inflammatories: Molecular docking studies for binding to some enzymes involved in inflammatory pathways. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2015, 62, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapitsas, P. Hydrolyzable tannin analysis in food. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parus, A. Antioxidant and pharmacological properties of phenolic acids. Postępy Fitoter. 2012, 1, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J. Profile of Bioactive Compounds in the Morphological Parts of Wild Fallopia japonica (Houtt) and Fallopia sachalinensis (F. Schmidt) and Their Antioxidative Activity. Molecules 2019, 24, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Djeridane, A.; Yousfi, M.; Nadjemi, B.; Boutassouna, D.; Stocker, P.; Vidal, N. Antioxidant activity of some algerian medicinal plants extracts containing phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2006, 97, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinic, V.; Milos, M.; Kulisic, T.; Jukić, M. Screening of 70 medicinal plant extracts for antioxidant capacity and total phenols. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunyanga, C.N.; Imungi, J.K.; Okoth, M.W.; Biesalski, H.K.; Vadivel, V. Total phenolic content, antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of methanolic extract of raw and traditionally processed Kenyan indigenous food ingredients. LWT 2012, 45, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koska, J.; Yassine, H.; Trenchevska, O.; Sinari, S.; Schwenke, D.C.; Yen, F.T.; Billheimer, D.; Nelson, R.W.; Nedelkov, B.; Reaven, P.D. Disialylated apolipoprotein C-III proteoform is associated with improved lipids in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes1[S]. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, M.-P.; Liao, M.; Dai, C.; Chen, J.-F.; Yang, C.-J.; Liu, M.; Chen, Z.-G.; Yao, M.-C. Sanguisorba officinalis L synergistically enhanced 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity in colorectal cancer cells by promoting a reactive oxygen species-mediated, mitochondria-caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, J.-A.; Kim, J.-S.; Kwon, K.-H.; Nam, J.-S.; Jung, J.-Y.; Cho, N.-P.; Cho, S.-D. Apoptotic effect of hot water extract of Sanguisorba officinalis L. in human oral cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, M.-P.; Li, W.; Dai, C.; Lam, C.W.K.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.-F.; Chen, Z.-G.; Zhang, W.; Yao, M. Aqueous extract of Sanguisorba officinalis blocks the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in colorectal cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10197–10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free. Radic. Boil. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakai, M.; Fukui, Y.; Asami, S.; Toyoda-Ono, Y.; Iwashita, T.; Shibata, H.; Mitsunaga, T.; Hashimoto, A.F.; Kiso, Y. Inhibitory effects of oolong tea polyphenols on pancreatic lipase in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4593–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsędek, A.; Majewska, I.; Redzynia, M.; Sosnowska, D.; Koziolkiewicz, M. In vitro inhibitory effect on digestive enzymes and antioxidant potential of commonly consumed fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4610–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickavar, B.; Yousefian, N. Evaluation of α-amylase inhibitory activities of selected antidiabetic medicinal plants. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2010, 6, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Compounds | Rt [min] | Δ [nm] | MS/MS | F ‡ | L | R | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolyzable Tannins | ||||||||

| 1 | 2,3-HHDP-(α/β)-glucose | 1.31 | 272 | 481/463/301 | x | |||

| 2 | HHDP-hex(2,3-(S)-Hexahydroxydiphenoyl-d-glucose) | 1.34 | 314 | 481/332/301/182 | x | x | x | x |

| 3 | HHDP-hexoside(1-galloyl-2,3-hexahydroxydiphenoyl-α-glucose) | 1.41 | 218 | 481/301/275/257/229 | x | |||

| 4 | HHDP-hex(2,3-(S)-Hexahydroxydiphenoyl-d-glucose) | 1.50 | 314 | 481/330/306/301/203/182 | x | x | x | x |

| 5 | Galloyl-hexoside(β-glucogallin) | 1.86 | 278 | 331/169 | x | |||

| 6 | Galloyl-pentoside | 1.99 | 274 | 301/169 | x | |||

| 7 | Galloyl-hexoside | 2.08 | 272 | 331/169 | x | |||

| 8 | Galloyl-hexoside | 2.09 | 268 | 331/169 | x | |||

| 10 | Galloyl-hexoside | 2.52 | 278 | 331/169 | x | x | ||

| 13 | Galloyl-hexoside | 3.08 | 273 | 331/169 | x | |||

| 14 | Di-galloyl-HHDP-glucose (tellimagrandin I) | 3.16 | 236/322 | 785/633/615/483/301 | x | x | x | |

| 15 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 3.34 | 230, 275 sh | 783/481/301/257 | x | x | x | x |

| 17 | Methyl-6-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 3.54 | 274 | 345/169/124.99 | x | x | ||

| 18 | Pedunculagin1 | 3.67 | 279 | 783/481/301 | x | |||

| 20 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 3.90 | 230, 275 sh | 783/481/301/257 | x | |||

| 23 | Pedunculagin1 | 4.05 | 324 | 783/481/301 | x | |||

| 24 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 4.15 | 230, 275 sh | 783/481/301/257 | x | |||

| 25 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose (corilagin isomer) | 4.18 | 235, 280 sh | 633/300.99 | x | |||

| 26 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 4.24 | 326 | 783/481/301/257 | x | |||

| 27 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 4.24 | 230, 275 sh | 783/481/301/257 | x | x | ||

| 28 | β-1-O-galloyl-2,3-(S)-HHDP-d-glucose | 4.30 | 326 | 633/617/595/515/454/432/ 319/297/179 | x | x | x | |

| 29 | Pedunculagin1 | 4.30 | 279 | 783/481/301 | x | |||

| 30 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 4.40 | 313 | 783/613/447/423/274/211/ 196/169 | x | x | x | |

| 34 | Di-HHDP-glucoside | 4.54 | 273 | 783/481/301 | x | |||

| 35 | Methylellagic acid-pentose | 4.55 | 324 | 447/315/301 | x | x | x | |

| 37 | Di-galloyl-glucoside | 4.59 | 273 | 483/313/169 | x | |||

| 44 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose | 4.98 | 219/276 | 633/463/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 47 | HHDP-NHTP-glucose (castalagin/vescalagin) | 5.08 | 219 | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | x | x | x |

| 49 | HHDP-glucose | 5.30 | 222 | 481/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 50 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 5.39 | 212 | 497/345/169 | x | x | x | x |

| 51 | HHDP-NHTP-glucose (castalagin/vescalagin) | 5.44 | 282/343 | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | |||

| 53 | HHDP-galloyl-glucose | 5.50 | 318 | 633/463/301/273/257/229/201/185 | x | |||

| 54 | Galloylglucoronide | 5.52 | 276 | 345/169 | x | |||

| 55 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose (corilagin isomer) | 5.55 | 218 | 633/463/301 | x | |||

| 56 | Di-galloyl-HHDP-glucose (tellimagrandin I) | 5.63 | 230, 280 sh | 785/633/615/483/301 | x | x | ||

| 58 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 5.69 | 230, 285 sh | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | x | ||

| 60 | Ellagic acid-pentoside | 5.73 | 330 | 433/300.99 | x | x | x | |

| 62 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 5.90 | 216 | 497/345/169 | x | x | x | x |

| 64 | Methyl-6-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 5.97 | 374 | 345/169/124.99 | x | x | x | |

| 66 | Di-galloyl-HHDP-glucose (tellimagrandin I) | 6.01 | 203/279 | 785/633/615/483/301 | x | |||

| 67 | Ellagic acid hexoside1 | 6.05 | 251/362 | 463/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 68 | Ellagic acid hexoside | 6.09 | 329 | 463/301 | x | |||

| 70 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 6.15 | 230, 285 sh | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | |||

| 71 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 6.19 | 213 | 497/345/169 | x | x | x | |

| 72 | Di-galloyl hexoside | 6.22 | 203 | 483/301/169 | x | |||

| 73 | Eucaglobulin | 6.23 | 276 | 497/345/327/313/183/169 | x | x | x | |

| 75 | Eucaglobulin | 6.25 | 270 | 497/345/327/313/183/169 | x | x | x | |

| 77 | Galloyl-HHDP-hexoside | 6.30 | 215 | 633/301 | x | |||

| 79 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 6.37 | 230, 285 sh | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | x | x | x |

| 81 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 6.41 | 222 | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | x | x | |

| 82 | HHDP-NHTP-glucose-galloyl-di-HHDP-glucose (cocciferind2) | 6.46 | 224 | 933/915/633/631/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 84 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 6.51 | 221 | 935/917/873//783/633/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 85 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 6.55 | 225, 280 sh | 935/917/873//783/633/301 | x | |||

| 86 | Lambertianin C | 6.58 | 250 | 1401/1237/935/633303 | x | x | x | x |

| 88 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 6.66 | 212 | 497/345/169 | x | |||

| 92 | Trigalloyl-HHDP-glucose | 6.93 | 251 nm | 937/767/635/465/301 | x | |||

| 93 | Ellagic acid-hexoside-pentoside | 6.99 | 253/361 | 595/433/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 94 | Ellagic acid-hexoside-pentoside | 7.04 | 247/361 | 595/433/301 | x | |||

| 95 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 7.06 | 253/357 | 935/917/873//783/633/301 | x | |||

| 97 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 7.13 | 221 | 935/917/873//783/633/301 | x | |||

| 98 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 7.14 | 230, 285 sh | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | |||

| 99 | Ellagic acid pentoside | 7.23 | 254/361 | 433/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 100 | Tetragalloyl-glucose | 7.27 | 227 | 787/635/617/573/465/403 | x | |||

| 102 | Ellagic acid hexoside | 7.34 | 254/362 | 463/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 104 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 7.41 | 218 | 935/917/873//783/633/301 | x | |||

| 106 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 7.43 | 219 | 935/917/873//783/633/301 | x | x | ||

| 108 | Ellagic acid a | 7.50 | 255/365 | 300.99 | x | x | x | x |

| 110 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 7.81 | 250/373 | 933/915/889/871/631/613/587/569 | x | |||

| 111 | Pentagalloylglucoside | 8.04 | 280 | 939/769/617/465/313/169 | x | |||

| 113 | Methyl galloyl-glucoside | 8.24 | 297/325 | 345/183 | x | |||

| 114 | Trigalloyl-HHDP- glucose | 8.26 | 259/360 | 937/7767/301 | x | |||

| 115 | Trigalloyl-β-D-methyl glucoside | 8.35 | 263/356 | 649/497/479/345 | x | |||

| 118 | Di-galloyl hexoside | 8.54 | 261/374 | 483/301 | x | |||

| 127 | 3,3′,4′-O-trimethyl ellagic acid | 9.66 | 352 | 343/328 | x | |||

| 128 | 3,3′,4′-O-trimethyl ellagic acid | 9.79 | 353 | 343/328 | x | |||

| 129 | 3,4′-O-dimethyl ellagic acid | 10.55 | 249/359 | 329/314/298/285 | x | |||

| 130 | 3,4′-O-dimethyl ellagic acid | 11.11 | 247/362 | 329/314/298/285 | x | |||

| Sanguiin | ||||||||

| 11 | Sanguiin H-6 | 2.74 | 234/320 | 1870/1567/1265/933/631/301 | x | x | x | |

| 41 | Sanguiin H-4 | 4.84 | 235/280 sh | 633/300.99 | x | |||

| 48 | Sanguiin H-10 isomer | 5.23 | 313 | 1567/1265/1103/933/301 | x | x | x | |

| 65 | Sanguiin H-1 | 5.99 | 230/280 sh | 785/633/465/301 | x | |||

| 69 | Sanguiin H-1 | 6.13 | 254/371 | 785/633/465/301 | x | x | x | |

| 89 | Sanguiin H-6 | 6.75 | 236 | 1870/1567/1265/933/631/301 | x | x | x | x |

| 96 | Sanguiin H-1 | 7.12 | 221 | 785/633/465/301 | x | x | ||

| 119 | Sanguiin H-7 | 8.59 | 261/361 | 801/649/301 | x | |||

| 122 | Sanguiin H-7 isomer | 9.05 | 334 | 801/649/301 | x | x | x | |

| Sanguisorbic acids | ||||||||

| 9 | Sanguisorbic acid dilactone | 2.13 | 272 | 469/314/301/286 | x | x | ||

| 12 | Sanguisorbic acid dilactone | 2.89 | 275 | 469/314/301/286 | x | |||

| 52 | Sanguisorbic acid glucoside | 5.47 | 325 | 667/285 | x | x | ||

| Phenolic acids | ||||||||

| 16 | Caffeoylquinic acid a | 3.50 | 322 | 353/191/179/161 | x | x | ||

| 19 | 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid a | 3.72 | 323 | 353/191/179/135 | x | x | x | |

| 32 | 3-O-p-coumaroylquinic acid a | 4.50 | 311 | 337163 | x | x | ||

| 33 | Rosmarinic acid | 4.54 | 325 | 359/191/179/173/163/152 | x | x | ||

| 42 | 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid a | 4.87 | 324 | 353/191/179 | x | x | x | |

| 78 | 3-O-feruloylquinic acid a | 6.36 | 324 | 367/193/191 | x | x | x | |

| 116 | Disuccinoyl-caffeoylquinic acids | 8.41 | 326 | 553/537/515/375/353/191/ 179/173 | x | x | x | |

| 120 | 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid | 8.83 | 326 | 515/353/191/179/173 | x | x | x | |

| 121 | 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid | 8.91 | 326 | 515/353/191/179/173 | x | x | x | |

| 123 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 9.27 | 325 | 503/341/179 | x | x | x | |

| 124 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 9.36 | 313 | 503/341/179 | x | x | x | |

| 125 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 9.50 | 326 | 503/341/179 | x | x | x | |

| 126 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 9.64 | 326 | 503/341/179 | x | |||

| Anthocyanins | ||||||||

| 21 | Cyanidin 3,5-O-diglucoside | 3.91 | 520 | 611/449/287 | x | |||

| 46 | Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside a | 5.05 | 516 | 449/287 | x | |||

| 76 | Cyanidin 3-O-malonylglucoside | 6.28 | 517 | 535/287 | x | |||

| 87 | Cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside | 6.60 | 518 | 595/449/287 | x | |||

| 90 | Cyanidin 3-O-malonylglucoside | 6.77 | 517 | 535/287 | x | |||

| 91 | Cyanidin 3-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside | 6.91 | 518 | 491/317/303/287 | x | |||

| Catechins and Proanthocyanidins | ||||||||

| 31 | (+)-Catechin a | 4.43 | 281 | 289 | x | x | x | x |

| 36 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer a | 4.58 | 276 | 577/289 | x | x | x | |

| 38 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer a | 4.67 | 279 | 577/289 | x | x | ||

| 39 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer a | 4.69 | 279 | 577/289 | x | x | x | |

| 40 | (−)-Epicatechin a | 4.83 | 279 | 289 | x | x | x | x |

| 43 | B-type (epi)catechin trimmer | 4.94 | 280 | 865/577/289 | x | |||

| 57 | B-type (epi)catechin tetramer | 5.63 | 278 | 1153/863/577/289 | x | x | x | x |

| 59 | B-type (epi)catechin tetramer | 5.70 | 278 | 1153/863/577/290 | x | x | x | x |

| 63 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer a | 5.90 | 274 | 577/289 | x | x | x | x |

| 74 | A-type procyanidins tetramer | 6.23 | 221/273 | 1153/865/575/ | x | |||

| 80 | B-type (epi)catechin tetramer | 6.41 | 278 | 1153/863/577/289 | x | |||

| 83 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer a | 6.46 | 276 | 577/289 | x | |||

| Flavonols | ||||||||

| 45 | Quercetin 3-O-glucoside a | 5.03 | 358 | 463/301 | x | x | ||

| 61 | Kaempferol-di-O-rhamnoside | 5.80 | 350 | 577/431/285 | x | x | x | |

| 101 | Quercetin 3-O-(6″-galloylglucose) | 7.30 | 224 | 615/463/300.027 | x | |||

| 103 | Taxifolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 7.35 | 229 | 465/285 | x | |||

| 105 | Quercetin-glucoside-rhamnoside-rhamnoside | 7.41 | 254/337 | 755/609/463/300.027 | x | x | x | |

| 107 | Quercetin rhamnosyl-rutinoside | 7.47 | 368 | 755/609/301 | x | x | x | |

| 109 | Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | 7.68 | 255/353 | 477/300.027 | x | x | x | x |

| 112 | Quercetin 3-O-acetyl glucoside | 8.15 | 355 | 505/300.027 | x | x | x | |

| 117 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide | 8.49 | 347 | 461/285 | x | x | ||

| Triterpenoid saponins | ||||||||

| 22 | Sanguisorbigenin | 3.98 | 223/271 | 453/345/183/169 | x | x | x | |

| Compounds | Flower | Leaves | Roots | Stalk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolyzable tannins | |||||

| 1 | 2,3-HHDP-(α/β)-glucose | nd ‡ | nd | 12.33 ± 0.25a † | nd |

| 2 | HHDP-hex(2,3-(S)-Hexahydroxydiphenoyl-d-glucose) | 141.89 ± 2.84a | 102.71 ± 2.05b | 13.28 ± 0.27c | 11.49 ± 0.23c |

| 3 | HHDP-hexoside(1-galloyl-2,3-hexahydroxydiphenoyl-α-glucose) | nd | 14.36 ± 0.29a | nd | nd |

| 4 | HHDP-hex(2,3-(S)-Hexahydroxydiphenoyl-d-glucose) | 161.00 ± 3.22a | 63.35 ± 1.27b | 40.73 ± 0.81c | 12.49 ± 0.25d |

| 5 | Galloyl-hexoside(β-glucogallin) | nd | nd | 92.13±1.84a | nd |

| 6 | Galloyl-pentoside | nd | nd | 38.51±0.77a | nd |

| 7 | Galloyl-hexoside | nd | nd | 20.66±0.41a | nd |

| 8 | Galloyl-hexoside | nd | 13.89 ± 0.28a | nd | nd |

| 10 | Galloyl-hexoside | nd | 5.18 ± 0.10b | nd | 9.52 ± 0.19a |

| 13 | Galloyl-hexoside | nd | 4.41 ± 0.09a | nd | nd |

| 14 | Di-galloyl-HHDP-glucose (tellimagrandin I) | 5.57 ± 0.11a | 6.34 ± 0.13a | nd | 1.35 ± 0.03b |

| 15 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 100.66 ± 2.01b | 24.25 ± 0.49c | 136.03 ± 2.72a | 15.78 ± 0.32d |

| 17 | Methyl-6-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | nd | nd | 234.27 ± 4.69a | 7.20 ± 0.14b |

| 18 | Pedunculagin1 | 2.55 ± 0.05a | nd | nd | nd |

| 20 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 2.23 ± 0.04a | nd | nd | nd |

| 23 | Pedunculagin1 | 9.08 ± 0.18a | nd | nd | nd |

| 24 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 20.00 ± 0.40a | nd | nd | nd |

| 25 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose (corilagin isomer) | nd | nd | 29.73 ± 0.59a | nd |

| 26 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | nd | 17.21 ± 0.34a | nd | nd |

| 27 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 97.32 ± 1.95a | nd | 42.58 ± 0.85b | nd |

| 28 | β-1-O-galloyl-2,3-(S)-HHDP-d-glucose | 513.20 ± 10.26a | 433.89±8.68b | nd | 83.52 ± 1.67c |

| 29 | Pedunculagin1 | nd | nd | 24.37 ± 0.49a | nd |

| 30 | Di-HHDP-glucose (pedunculagin isomer) | 9.66 ± 0.19b | 11.96 ± 0.24a | nd | 2.01 ± 0.04c |

| 34 | Di-HHDP-glucoside | nd | nd | 19.51 ± 0.39a | 0 |

| 35 | Methylellagic acid-pentose | 26.83 ± 0.54a | 5.45 ± 0.11c | nd | 8.17 ± 0.16b |

| 37 | Di-galloyl-glucoside | nd | nd | 53.85 ± 1.08a | nd |

| 44 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose | 165.31 ± 3.31a | 8.65 ± 0.17c | 145.15 ± 2.90b | 5.25 ± 0.11d |

| 47 | HHDP-NHTP-glucose (castalagin/vescalagin) | 87.29 ± 1.75b | 100.59 ± 2.01a | 41.30 ± 0.83c | 23.36 ± 0.47d |

| 49 | HHDP-glucose | 97.26 ± 1.95a | 45.3 ± 0.91b | 11.32 ± 0.23c | 11.44 ± 0.23c |

| 50 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 7.94 ± 0.16b | 1.06 ± 0.02c | 17.12 ± 0.34a | 0.58 ± 0.01d |

| 51 | HHDP-NHTP-glucose (castalagin/vescalagin) | nd | nd | 24.08 ± 0.48a | nd |

| 53 | HHDP-galloyl-glucose | 43.97 ± 0.88a | nd | nd | nd |

| 54 | Galloylglucoronide | nd | nd | 93.44 ± 1.87a | nd |

| 55 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose (corilagin isomer) | nd | 22.90 ± 0.46a | nd | nd |

| 56 | Di-galloyl-HHDP-glucose (tellimagrandin I) | 85.77 ± 1.72a | 35.62 ± 0.71b | nd | nd |

| 58 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 37.38 ± 0.75a | 70.71 ± 1.41b | nd | nd |

| 60 | Ellagic acid-pentoside | 9.31 ± 0.19b | 13.70 ± 0.27a | nd | 3.96 ± 0.08c |

| 62 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 256.75 ± 5.14a | 104.29 ± 2.09b | 254.04 ± 5.08a | 71.93 ± 1.44c |

| 64 | Methyl-6-O-galloyl-β-d-glucopyranoside | 6.75 ± 0.14b | 10.71 ± 0.21a | nd | 3.47 ± 0.07c |

| 66 | Di-galloyl-HHDP-glucose (tellimagrandin I) | nd | nd | 13.52 ± 0.27a | nd |

| 67 | Ellagic acid hexoside | 5.76 ± 0.12b | 7.16 ± 0.14a | 4.05 ± 0.08b | 2.61 ± 0.05c |

| 68 | Ellagic acid hexoside | nd | nd | nd | 4.53 ± 0.09a |

| 70 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | nd | nd | 68.46 ± 1.37a | nd |

| 71 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | nd | 1.80 ± 0.04a | 1.70 ± 0.03a | 0.58 ± 0.01b |

| 72 | Di-galloyl hexoside | nd | nd | 43.6±0.87a | nd |

| 73 | Eucaglobulin | 51.84 ± 1.04b | 102.83 ± 2.06a | nd | 16.79 ± 0.34c |

| 75 | Eucaglobulin | 71.19 ± 1.42a | 71.72 ± 1.43a | nd | 22.59 ± 0.45b |

| 77 | Galloyl-HHDP-hexoside | nd | nd | 106.23 ± 2.12a | nd |

| 79 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | 26.13 ± 0.52c | 62.30 ± 1.25a | 52.75 ± 1.06b | 14.52 ± 0.29d |

| 81 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | nd | 92.82 ± 1.86a | 67.43 ± 1.35b | 13.19 ± 0.26c |

| 82 | HHDP-NHTP-glucose-galloyl-di-HHDP-glucose (cocciferind2) | 87.01 ± 1.74b | 41.02 ± 0.82c | 155.76 ± 3.12a | 13.57 ± 0.27d |

| 84 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 38.45 ± 0.77b | 132.33 ± 2.65a | 32.87 ± 0.66c | 30.56 ± 0.61c |

| 85 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | nd | nd | 52.26 ± 1.05a | nd |

| 86 | Lambertianin C | 3029.28 ± 60.59a | 2232.84 ± 44.66b | 898.98 ± 17.98d | 1236.77 ± 24.74c |

| 88 | Methyl-4,6-digalloyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | nd | nd | 4.82 ± 0.1a | nd |

| 92 | Trigalloyl-HHDP-glucose | nd | nd | 86.34 ± 1.73a | nd |

| 93 | Ellagic acid-hexoside-pentoside | 33.54 ± 0.67a | 32.53 ± 0.65a | 32.80 ± 0.66a | 7.09 ± 0.14b |

| 94 | Ellagic acid-hexoside-pentoside | nd | 51.34 ± 1.03a | nd | nd |

| 95 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | nd | nd | 12.48 ± 0.25a | nd |

| 97 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 30.53 ± 0.61a | nd | nd | nd |

| 98 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | nd | nd | nd | 43.38 ± 0.87a |

| 99 | Ellagic acid pentoside | 14.50 ± 0.29b | 15.22 ± 0.3b | 18.07 ± 0.36a | 3.47 ± 0.07c |

| 100 | Tetragalloyl-glucose | nd | nd | 328.94 ± 6.58a | nd |

| 102 | Ellagic acid hexoside1 | 1.14 ± 0.02a | 0.33 ± 0.01c | 0.61 ± 0.01b | 0.36 ± 0.01c |

| 104 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | nd | 56.41 ± 1.13a | nd | nd |

| 106 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose (potentilin/casuarictin isomer) | 202.46 ± 4.05a | nd | 147.72 ± 2.95b | nd |

| 108 | Ellagic acid | 17.69 ± 0.35c | 26.90 ± 0.54a | 13.49 ± 0.27b | 5.20 ± 0.10d |

| 110 | Castalagin/vescalagin isomer | nd | nd | 1.91 ± 0.04a | nd |

| 111 | Pentagalloylglucoside | nd | nd | 36.57 ± 0.73a | nd |

| 113 | Methyl galloyl-glucoside | nd | 13.75 ± 0.28a | nd | nd |

| 114 | Trigalloyl-HHDP- glucose | nd | nd | 0.71 ± 0.01a | nd |

| 115 | Trigalloyl-β-D-methyl glucoside | nd | nd | 35.65 ± 0.71a | nd |

| 118 | Di-galloyl hexoside | nd | nd | 3.61 ± 0.07a | nd |

| 127 | 3,3′,4′-O-trimethyl ellagic acid | nd | 31.41 ± 0.63a | nd | nd |

| 128 | 3,3′,4′-O-trimethyl ellagic acid | nd | 1.47 ± 0.03a | nd | nd |

| 129 | 3,4′-O-dimethyl ellagic acid | nd | nd | 49.05 ± 0.98a | nd |

| 130 | 3,4′-O-dimethyl ellagic acid | nd | nd | 251.11 ± 5.02a | nd |

| SUM | 5497.24 ± 109.94a | 4090.71 ± 81.81b | 3865.92 ± 77.32c | 1686.73 ± 33.73d | |

| Sanguiin | |||||

| 11 | Sanguiin H-6 | 2.57 ± 0.05b | 10.13 ± 0.20a | nd | 1.22 ± 0.02c |

| 41 | Sanguiin H-4 | 352.14 ± 7.04a | nd | nd | nd |

| 48 | Sanguiin H-10 isomer | 130.92 ± 2.62a | 5.33 ± 0.11b | nd | 4.14 ± 0.08b |

| 65 | Sanguiin H-1 | 43.36 ± 0.87 | nd | nd | nd |

| 69 | Sanguiin H-1 | nd | 1.01 ± 0.02b | 2.95 ± 0.06a | 0.15 ± 0.01c |

| 89 | Sanguiin H-6 | 3566.15 ± 71.32a | 621.04 ± 12.42d | 763.91 ± 15.28c | 289.86 ± 5.80b |

| 96 | Sanguiin H-1 | nd | 61.95 ± 1.24b | 730.22 ± 14.60a | nd |

| 119 | Sanguiin H-7 | nd | nd | 4.42 ± 0.09a | nd |

| 122 | Sanguiin H-7 isomer | 1.89 ± 0.04a | 2.24 ± 0.04a | nd | 0.98 ± 0.02b |

| SUM | 4097.03 ± 81.94a | 701.7 ± 14.03c | 1501.5 ± 30.03b | 296.35 ± 5.93d | |

| Sanguisorbic acids | |||||

| 9 | Sanguisorbic acid dilactone | nd | 6.61 ± 0.13d | 10.95 ± 0.22a | nd |

| 12 | Sanguisorbic acid dilactone | nd | nd | 15.44 ± 0.31a | nd |

| 52 | Sanguisorbic acid glucoside | nd | 109.18 ± 2.18a | nd | 13.43 ± 0.27b |

| SUM | nd | 115.79 ± 2.32a | 26.39 ± 0.53b | 13.43 ± 0.27c | |

| Phenolic acids | |||||

| 16 | Caffeoylquinic acid | 23.07 ± 0.46b | 47.52 ± 0.95a | nd | nd |

| 19 | Caffeoylquinic acid | 539.00 ± 10.78b | 1363.67 ± 27.27a | nd | 182.92 ± 3.66c |

| 32 | 3-p-Coumaroylquinic acid | 87.17 ± 1.74a | 42.55 ± 0.85b | nd | nd |

| 33 | Rosmarinic acid | nd | 8.39 ± 0.17a | nd | 2.98 ± 0.06b |

| 42 | 5-Caffeoylquinic acid | 673.42 ± 13.47a | 436.44 ± 8.73b | nd | 129.09 ± 2.58c |

| 78 | 3-Feruloylquinic acid | 11.46 ± 0.23a | 4.95 ± 0.10b | nd | 3.17 ± 0.06c |

| 116 | Disuccinoyl-caffeoylquinic acids | 69.02 ± 1.38b | 89.00 ± 1.78a | nd | 31.51 ± 0.63c |

| 120 | Di-caffeoylquinic | 4.81 ± 0.10b | 17.66 ± 0.35a | nd | 2.79 ± 0.06c |

| 121 | Dicaffeoylquinic | 4.12 ± 0.08c | 12.78 ± 0.26a | nd | 1.33 ± 0.03c |

| 123 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 2.72 ± 0.05b | 6.68 ± 0.13a | nd | 3.10 ± 0.06b |

| 124 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 13.38 ± 0.27a | 8.47 ± 0.17b | nd | 2.04 ± 0.04c |

| 125 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 3.51 ± 0.07b | 6.26 ± 0.13a | nd | 2.23 ± 0.04c |

| 126 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | nd | nd | 6.64 ± 0.13a | nd |

| SUM | 1431.68 ± 28.63b | 2044.37 ± 40.89a | 6.64 ± 0.13d | 361.16 ± 7.22c | |

| Anthocyanins | |||||

| 21 | Cyanidin 3,5-O-diglucoside | 19.56 ± 0.39a | nd | nd | nd |

| 46 | Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | 339.87 ± 6.80a | nd | nd | nd |

| 76 | Cyanidin 3-O-malonylglucoside | 154.35 ± 3.09a | nd | nd | nd |

| 87 | Cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside | 4.83 ± 0.10a | nd | nd | nd |

| 90 | Cyanidin 3-O-malonylglucoside | 14.40 ± 0.29a | nd | nd | nd |

| 91 | Cyanidin 3-(6-O-acetyl)glucoside | 16.56 ± 0.33a | nd | nd | nd |

| SUM | 549.57 ± 10.99a | nd | nd | nd | |

| Catechins and Proanthocyanins | |||||

| 31 | (+)-Catechin | 46.77 ± 0.94d | 160.08 ± 3.20b | 374.41 ± 7.49a | 133.37 ± 2.67c |

| 36 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer | 111.05 ± 2.22a | 33.03 ± 0.66b | nd | 28.85 ± 0.58c |

| 38 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer | nd | 19.88 ± 0.40b | 383.49 ± 7.67a | nd |

| 39 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer | 136.33 ± 2.73a | 15.04 ± 0.30c | nd | 125.77 ± 2.52b |

| 40 | (−)-Epicatechin | 656.57 ± 13.13b | 138.19 ± 2.76d | 700.12 ± 14.00a | 457.66 ± 9.15c |

| 43 | B-type (epi)catechin trimmer | nd | nd | nd | 86.20 ± 1.72a |

| 57 | B-type (epi)catechin tetramer | 120.62 ± 2.41c | 45.32 ± 0.91d | 448.56 ± 8.97a | 142.85 ± 2.86b |

| 59 | B-type (epi)catechin tetramer | 57.12 ± 1.14a | 22.38 ± 0.45b | 21.69 ± 0.43b | 18.43 ± 0.37c |

| 63 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer | 760.26 ± 15.21b | 305.55 ± 6.11c | 796.86 ± 15.94a | 214.39 ± 4.29d |

| 74 | A-type procyanidin tetramer | nd | nd | 51.53 ± 1.03a | nd |

| 80 | B-type (epi)catechin tetramer | nd | nd | 105.67 ± 2.11a | nd |

| 83 | B-type (epi)catechin dimmer | nd | nd | 356.86 ± 7.14a | nd |

| SUM | 1888.72 ± 37.77b | 739.47 ± 14.79d | 3239.19 ± 64.78a | 1207.52 ± 24.15c | |

| Flavonols | |||||

| 45 | Quercetin 3-O-glucoside | nd | 15.00 ± 0.30a | nd | 4.15 ± 0.08b |

| 61 | Kaempferol-di-O-rhamnoside | 5.23±0.10a | 0.59 ± 0.01b | nd | 0.31 ± 0.01b |

| 101 | Quercetin 3-O-(6″-galloylglucose) | nd | 77.72 ± 1.55a | nd | nd |

| 103 | Taxifolin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | nd | nd | 43.41 ± 0.87a | nd |

| 105 | Quercetin-glucoside-rhamnoside-rhamnoside | 26.29 ± 0.53a | 9.93 ± 0.20c | nd | 13.33 ± 0.27b |

| 107 | Quercetin rhamnosyl-rutinoside | 5.93 ± 0.12a | 3.11 ± 0.06b | nd | 2.54 ± 0.05b |

| 109 | Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | 494.97 ± 9.90c | 1645.76 ± 32.92a | 4.13 ± 0.08d | 675.15 ± 13.50b |

| 112 | Quercetin 3-O-acetyl glucoside | 47.89 ± 0.96b | 54.56 ± 1.09a | nd | 26.73 ± 0.53c |

| 117 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide | 137.89 ± 2.76b | 163.18 ± 3.26a | nd | 65.65 ± 1.31c |

| SUM | 718.2 ± 14.36c | 1969.85 ± 39.40a | 47.54 ± 0.95d | 787.86 ± 15.76b | |

| Sanguisorbigenin | 262.53 ± 5.25b | 300.60 ± 6.01a | nd | 253.28 ± 5.07c | |

| Total mg/100 g d.w. | 14444.97 ± 288.90a | 9962.55 ± 199.25b | 8687.16 ± 173.74c | 4606.33 ± 92.13d |

| Components | α-Amylase [EC50 MG/ML] | α-Glucosidase [EC50 MG/ML] | Pancreatic Lipase [EC50 MG/ML] | ABTS [mmol/g d.b.] | FRAP [mmol/g d.b.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | 9.48 ± 0.24b ‡ | 11.86 ± 0.24b | 18.75 ± 0.38a | 6.63 ± 0.1a3 | 0.30 ± 0.01a |

| Flowers | 6.03 ± 0.19a | 9.60 ± 0.19a | 21.40 ± 0.43b | 5.56 ± 0.11b | 0.20 ± 0.01b |

| Stalks | 23.91 ± 0.63c | 31.74 ± 0.63d | 56.47 ± 1.13c | 0.52 ± 0.01d | 0.09 ± 0.01d |

| Roots | 10.44 ± 0.39b | 19.54 ± 0.39c | 72.68 ± 1.45d | 5.08 ± 0.10c | 0.13 ± 0.01c |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lachowicz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Rapak, A.; Ochmian, I. Profile and Content of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Flowers, Roots, and Stalks of Sanguisorba officinalis L. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis and Their In Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antiproliferative Potency. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13080191

Lachowicz S, Oszmiański J, Rapak A, Ochmian I. Profile and Content of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Flowers, Roots, and Stalks of Sanguisorba officinalis L. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis and Their In Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antiproliferative Potency. Pharmaceuticals. 2020; 13(8):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13080191

Chicago/Turabian StyleLachowicz, Sabina, Jan Oszmiański, Andrzej Rapak, and Ireneusz Ochmian. 2020. "Profile and Content of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Flowers, Roots, and Stalks of Sanguisorba officinalis L. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis and Their In Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antiproliferative Potency" Pharmaceuticals 13, no. 8: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13080191

APA StyleLachowicz, S., Oszmiański, J., Rapak, A., & Ochmian, I. (2020). Profile and Content of Phenolic Compounds in Leaves, Flowers, Roots, and Stalks of Sanguisorba officinalis L. Determined with the LC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS Analysis and Their In Vitro Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, Antiproliferative Potency. Pharmaceuticals, 13(8), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph13080191