PET Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Narrative Review with Focus on Novel PET Tracers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Indications for Cardiac PET/CT for CS

3. Patient Preparation for Cardiac PET/CT for CS

4. Acquisition of Cardiac PET/CT Images for CS

5. Interpretation of Cardiac PET/CT Images for CS

6. Diagnostic and Prognostic Performance of Cardiac PET/CT for CS

7. Cardiac PET/CT for Assessment of Treatment Response in CS

8. Treatment of CS

9. New PET Radiopharmaceuticals for Imaging of Inflammatory Diseases

10. Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analogs

11. Proliferation Tracers: Radiolabeled Thymidine and Choline Analogs

12. Hypoxia Tracers: Radiolabeled Nitroimidazoles

13. Radiolabeled Amino Acid Compounds: 11C-Methionine

14. Radiolabeled CXCR4 Receptor Ligand

15. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | cardiac sarcoidosis |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| FDG | fluorodeoxyglucose |

| JMHW | Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare |

| HRS | Heart Rhythm Society |

| SNMMI | Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging |

| CT | computed tomography |

| ASNC | American Society of Nuclear Cardiology |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MPI | myocardial perfusion imaging |

| SPECT | single-photon emission computed tomography |

| SUV | standard uptake value |

| UI | uptake index |

| SSTR | somatostatin receptor |

| FLT | fluorothymidine |

| FMISO | fluoromisonidazole |

| MIP | maximum intensity projection |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

References

- Hunninghake, G.W.; Costabel, U.; Ando, M.; Baughman, R.; Francois Cordier, J.; Du Bois, R.; Eklund, A.; Kitaichi, M.; Lynch, J.; Rizzato, G.; et al. Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 160, 736–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, O.; Abramovitz, L.; Wiley, A.S.; Cozier, Y.C.; Camargo, C.A. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in a prospective cohort study of U.S. women. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erdal, B.S.; Clymer, B.D.; Yildiz, V.O.; Julian, M.W.; Crouser, E.D. Unexpectedly high prevalence of sarcoidosis in a repre-sentative U.S. metropolitan population. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birnie, D.; Ha, A.C.; Gula, L.J.; Chakrabarti, S.; Beanlands, R.S.; Nery, P. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2015, 36, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, K.J.; Hutchins, G.M.; Bulkley, B.H. Cardiac sarcoid: A clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation 1978, 58, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, O.P.; Maheshwari, A.; Thaker, K. Myocardial sarcoidosis. Chest 1993, 103, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, Y.; Iwai, K.; Tachibana, T.; Fruie, T.; Shigematsu, N.; Izumi, T.; Homma, A.H.; Mikami, R.; Hongo, O.; Hiraga, Y.; et al. Clinicopathological study on fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1976, 278, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughan, A.R.; Williams, B.R. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart 2006, 92, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagana, S.M.; Parwani, A.V.; Nichols, L.C. Cardiac sarcoidosis: A pathology-focused review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2010, 134, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavora, F.; Cresswell, N.; Li, L.; Ripple, M.; Solomon, C.; Burke, A. Comparison of necropsy findings in patients with sarcoidosis dying suddenly from cardiac sarcoidosis versus dying suddenly from other causes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyplosz, B.; Marijon, E.; Dougados, J.; Pouchot, J. Sarcoidosis: An unusual cause of acute pericarditis. Acta Cardiol. 2010, 65, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubrey, S.W.; Falk, R.H. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 52, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.V.; Nazari, J.; Edelman, R.R. Coronary artery vasculitis as a presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis. Circulation 2012, 125, e344–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fleming, H.A. Sarcoid heart disease. Br. Med. J. 1986, 292, 1095–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, W.C.; McAllister, H.A.; Ferrans, V.J. Sarcoidosis of the heart. Am. J. Med. 1977, 63, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedema, J.P.; Snoep, G.; van Kroonenburgh, M.P.G.; van Geuns, R.-J.; Dassen, W.R.M.; Gorgels, A.P.; Crijns, H.J.G.M. Cardiac involvement in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis assessed at two university medical centers in the Netherlands. Chest 2005, 128, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, Y.; Isobe, M.; Hiroe, M.; Morimoto, S.-I.; Hiramitsu, S.; Nakano, T.; Izumi, T.; Sekiguchi, M. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am. J. Cardiol. 2001, 88, 1006–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusimaa, P.; Ylitalo, K.; Anttonen, O.; Kerola, T.; Virtanen, V.; Pääkkö, E.; Raatikainen, P. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia as a primary presentation of sarcoidosis. Europace 2008, 10, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandolin, R.; Lehtonen, J.; Graner, M.; Schildt, J.; Salmenkivi, K.; Kivistö, S.M.; Kupari, M. Diagnosing isolated cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 270, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, D.R.; Bravo, P.E.; Vita, T.; Agarwal, V.; Osborne, M.; Taqueti, V.R.; Skali, H.; Chareonthaitawee, P.; Dorbala, S.; Stewart, G.; et al. Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis: A focused review of an under-recognized entity. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipse, M.M.; Sauer, W.H. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2014, 16, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.Z.; Nakatani, S.; Zhang, G.; Tachibana, T.; Ohmori, F.; Yamagishi, M.; Kitakaze, M.; Tomoike, H.; Miyatake, K. Prevention of left ventricular remodeling by long-term corticosteroid therapy in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 95, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauwet, L.A.; Cooper, L.T. Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis and cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2013, 18, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langah, R.; Spicer, K.; Gebregziabher, M.; Gordon, L. Effectiveness of prolonged fasting 18f-FDG PET-CT in the detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2009, 16, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, H.; Shirai, N.; Tagaki, M.; Yoshiyama, M.; Akioka, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Yoshikawa, J. Identification of cardiac sarcoidosis with (13)N-NH(3)/(18)F-FDG PET. J. Nucl. Med. 2003, 44, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishimaru, S.; Tsujino, I.; Takei, T.; Tsukamoto, E.; Sakaue, S.; Kamigaki, M.; Ito, N.; Ohira, H.; Ikeda, D.; Tamaki, N.; et al. Focal uptake on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography images indicates cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis†. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 1538–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, G.; Leung, E.; Mylonas, I.; Nery, P.; Williams, K.; Wisenberg, G.; Gulenchyn, K.Y.; Dekemp, R.A.; DaSilva, J.; Birnie, D.; et al. The Use of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: A systematic review and metaanalysis including the Ontario experience. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 53, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiraga, H.; Iwai, K. Guidelines for Diagnosis of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Study Report on Diffuse Pulmonary Disease; The Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare: Tokyo, Japan, 1993; p. 2. (In Japanese).

- Terasaki, F.; Yoshinaga, K. New guidelines for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis in Japan. Ann. Nucl. Cardiol. 2017, 3, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birnie, D.H.; Sauer, W.H.; Bogun, F.; Cooper, J.M.; Culver, D.A.; Duvernoy, C.S.; Judson, M.A.; Kron, J.; Mehta, D.; Nielsen, J.C.; et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 2014, 11, 1304–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chareonthaitawee, P.; Beanlands, R.S.; Chen, W.; Dorbala, S.; Miller, E.; Murthy, V.L.; Birnie, D.H.; Chen, E.S.; Cooper, L.T.; Tung, R.H.; et al. Joint SNMMI–ASNC expert consensus document on the role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in cardiac sarcoid detection and therapy monitoring. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Camici, P.; Ferrannini, E.; Opie, L.H. Myocardial metabolism in ischemic heart disease: Basic principles and application to imaging by positron emission tomography. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1989, 32, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taegtmeyer, H. Tracing cardiac metabolism in vivo: One substrate at a time. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51 (Suppl. S1), 80S–87S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Manabe, O.; Yoshinaga, K.; Ohira, H.; Masuda, A.; Sato, T.; Tsujino, I.; Yamada, A.; Oyama-Manabe, N.; Hirata, K.; Nishimura, M.; et al. The effects of 18-h fasting with low-carbohydrate diet preparation on suppressed physiological myocardial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake and possible minimal effects of unfractionated heparin use in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Masuda, A.; Naya, M.; Manabe, O.; Magota, K.; Yoshinaga, K.; Tsutsui, H.; Tamaki, N. Administration of unfractionated heparin with prolonged fasting could reduce physiological 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the heart. Acta Radiol. 2016, 57, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morooka, M.; Moroi, M.; Uno, K.; Ito, K.; Wu, J.; Nakagawa, T.; Kubota, K.; Minamimoto, R.; Miyata, Y.; Okasaki, M.; et al. Long fasting is effective in inhibiting physiological myocardial 18F-FDG uptake and for evaluating active lesions of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2014, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harisankar, C.N.; Mittal, B.R.; Agrawal, K.L.; Abrar, M.L.; Bhattacharya, A. Utility of high fat and low carbohydrate diet in suppressing myocardial FDG uptake. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2011, 18, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M.T.; Hulten, E.A.; Murthy, V.L.; Skali, H.; Taqueti, V.R.; Dorbala, S.; DiCarli, M.F.; Blankstein, R. Patient preparation for cardiac fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of inflammation. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asmal, A.C.; Leary, W.P.; Thandroyen, F.; Botha, J.; Wattrus, S. A dose-response study of the anticoagulant and lipolytic activities of heparin in normal subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1979, 7, 531–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gormsen, L.C.; Christensen, N.L.; Bendstrup, E.; Tolbod, L.P.; Nielsen, S.S. Complete somatostatin-induced insulin suppression combined with heparin loading does not significantly suppress myocardial 18F-FDG uptake in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2013, 20, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, G.; Jouni, H.; Acharya, G.A.; Blauwet, L.A.; Kapa, S.; Bois, J.; Chareonthaitawee, P.; Rodriguez-Porcel, M.G. Suppressing physiologic 18-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in patients undergoing positron emission tomography for cardiac sarcoidosis: The effect of a structured patient preparation protocol. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilsizian, V.; Bacharach, S.L.; Beanlands, R.; Bergmann, S.R.; Delbeke, D.; Dorbala, S.; Gropler, R.J.; Knuuti, J.; Schelbert, H.R.; Travin, M.I. ASNC imaging guidelines/SNMMI procedure standard for positron emission tomography (PET) nuclear cardiology procedures. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 1187–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Delso, G.; Fürst, S.; Jakoby, B.; Ladebeck, R.; Ganter, C.; Nekolla, S.G.; Schwaiger, M.; Ziegler, S.I. Performance measurements of the Siemens mMR integrated whole-body PET/MR scanner. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gould, K.L.; Pan, T.; Loghin, C.; Johnson, N.P.; Guha, A.; Sdringola, S. Frequent diagnostic errors in cardiac PET/CT due to misregistration of CT attenuation and emission PET images: A definitive analysis of causes, consequences, and corrections. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFilippo, F.P.; Brunken, R.C. Do implanted pacemaker leads and ICD leads cause metal-related artifact in cardiac PET/CT? J. Nucl. Med. 2005, 46, 436–443. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, R.J.; Flaherty, K.R.; Jin, Z.; Bokhari, S. The prognostic value of quantitating and localizing F-18 FDG uptake in cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Pak, K.; Kim, K. Diagnostic performance of F-18 FDG PET for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis; A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 2103–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankstein, R.; Osborne, M.; Naya, M.; Waller, A.; Kim, C.K.; Murthy, V.; Kazemian, P.; Kwong, R.Y.; Tokuda, M.; Skali, H.; et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmadian, A.; Brogan, A.; Berman, J.; Sverdlov, A.L.; Mercier, G.; Mazzini, M.; Govender, P.; Ruberg, F.L.; Miller, E.J. Quantitative interpretation of FDG PET/CT with myocardial perfusion imaging increases diagnostic information in the evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muser, D.; Santangeli, P.; Castro, S.A.; Liang, J.J.; Enriquez, A.; Werner, T.J.; Nucifora, G.; Magnani, S.; Hayashi, T.; Zado, E.S.; et al. Prognostic role of serial quantitative evaluation of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by PET/CT in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis presenting with ventricular tachycardia. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2018, 45, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, M.; Soine, L.A.; Vesselle, H.J. Semi-quantitative metabolic values on FDG PET/CT including extracardiac sites of disease as a predictor of treatment course in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2017, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sperry, B.W.; Tamarappoo, B.K.; Oldan, J.D.; Javed, O.; Culver, D.A.; Brunken, R.; Cerqueira, M.D.; Hachamovitch, R. Prognostic impact of extent, severity, and heterogeneity of abnormalities on 18F-FDG PET scans for suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, M.; Swapna, N.; Ali, A.Z.; Saggu, D.K.; Yalagudri, S.; Kishore, J.; Swamy, L.N. and Narasimhan, C. Pre-treatment myocardial 18FDG uptake predicts response to immunosup-pression in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 2008–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, M.T.; Hulten, E.A.; Singh, A.; Waller, A.H.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Stewart, G.C.; Hainer, J.; Murthy, V.L.; Skali, H.; Dorbala, S.; et al. Reduction in 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on serial cardiac positron emission tomography is associated with improved left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Uemura, A.; Hiramitsu, S.; Ito, T.; Hishida, H. Efficacy of corticosteroids in sarcoidosis presenting with atrioventricular block. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. Off. J. WASOG 2003, 20, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Ballul, T.; Borie, R.; Crestani, B.; Daugas, E.; Descamps, V.; Dieude, P.; Dossier, A.; Extramiana, F.; van Gysel, D.; Papo, T.; et al. Treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis: A comparative study of steroids and steroids plus immunosuppressive drugs. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 276, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, N.; Guo, H.; Iagaru, A.; Mittra, E.; Fowler, M.; Witteles, R. Serial cardiac FDG-PET for the diagnosis and therapeutic guidance of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J. Card. Fail. 2019, 25, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.L.M.; Mathijssen, H.; Azzahhafi, J.; Swaans, M.; Veltkamp, M.; Keijsers, R.; Akdim, F.; Post, M.; Grutters, J. Effectiveness and safety of infliximab in cardiac sarcoidosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 330, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwazir, M.; Krause, M.L.; Bois, J.P.; Christopoulos, G.; Kendi, A.T.; Cooper, J.L.T.; Jouni, H.; Abouezzeddine, O.F.; Chareonthaitawee, P.; Abdelshafee, M.; et al. Rituximab for the treatment of refractory cardiac sarcoidosis: A single-center experience. J. Cardiac Fail. 2021. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengel, F.M.; Ross, T.L. Emerging imaging targets for infiltrative cardiomyopathy: Inflammation and fibrosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rufini, V.; Calcagni, M.L.; Baum, R.P. Imaging of neuroendocrine tumors. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2003, 36, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebtahi, R.; Crestani, B.; Belmatoug, N.; Daou, D.; Genin, R.; Dombret, M.C.; Palazzo, E.; Faraggi, M.; Aubier, M.; Le Guludec, D. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and gallium scintigraphy in patients with sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Med. 2001, 42, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwekkeboom, D.J.; Krenning, E.P.; Kho, G.S.; Breeman, W.A.P.; Van Hagen, P.M. Somatostatin receptor imaging in patients with sarcoidosis. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 1998, 25, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, A.; Thamake, S.; Tworowska, I.; Ranganathan, D.; Delpassand, E.S. The value of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors compared to current FDA approved imaging modalities: A review of literature. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 4, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Gormsen, L.C.; Haraldsen, A.; Kramer, S.; Dias, A.H.; Kim, W.Y.; Borghammer, P. A dual tracer 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT pilot study for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2016, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lapa, C.; Reiter, T.; Kircher, M.; Schirbel, A.; Werner, R.A.; Pelzer, T.; Pizarro, C.; Skowasch, D.; Thomas, L.; Schlesinger-Irsch, U.; et al. Somatostatin receptor based PET/CT in patients with the suspicion of cardiac sarcoidosis: An initial comparison to cardiac MRI. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77807–77814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, P.E.; Bajaj, N.; Padera, R.F.; Morgan, V.; Hainer, J.; Bibbo, C.F.; Harrington, M.; Park, M.-A.; Hyun, H.; Robertson, M.; et al. Feasibility of somatostatin receptor-targeted imaging for detection of myocardial inflammation: A pilot study. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, A.F.; Grierson, J.R.; Dohmen, B.M.; Machulla, H.-J.; Stayanoff, J.C.; Lawhorn-Crews, J.M.; Obradovich, J.E.; Muzik, O.; Mangner, T.J. Imaging proliferation in vivo with [F-18]FLT and positron emission tomography. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 1334–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Waarde, A.; Cobben, D.C.; Suurmeijer, A.J.; Maas, B.; Vaalburg, W.; de Vries, E.F.; Jager, P.L.; Hoekstra, H.J. and Elsinga, P.H. Selectivity of 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG for differentiating tumor from in-flammation in a rodent model. J. Nucl. Med. 2004, 45, 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Sherley, J.L.; Kelly, T.J. Regulation of human thymidine kinase during the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 8350–8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Kuge, Y.; Kohanawa, M.; Takahashi, T.; Zhao, Y.; Yi, M.; Kanegae, K.; Seki, K.-I.; Tamaki, N. Usefulness of 11C-Methionine for differentiating tumors from granulomas in experimental rat models: A comparison with 18F-FDG and 18F-FLT. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martineau, P.; Pelletier-Galarneau, M.; Juneau, D.; Leung, E.; Birnie, D.; Beanlands, R.S.B. Molecular imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis. Curr. Cardiovasc. Imaging Rep. 2018, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

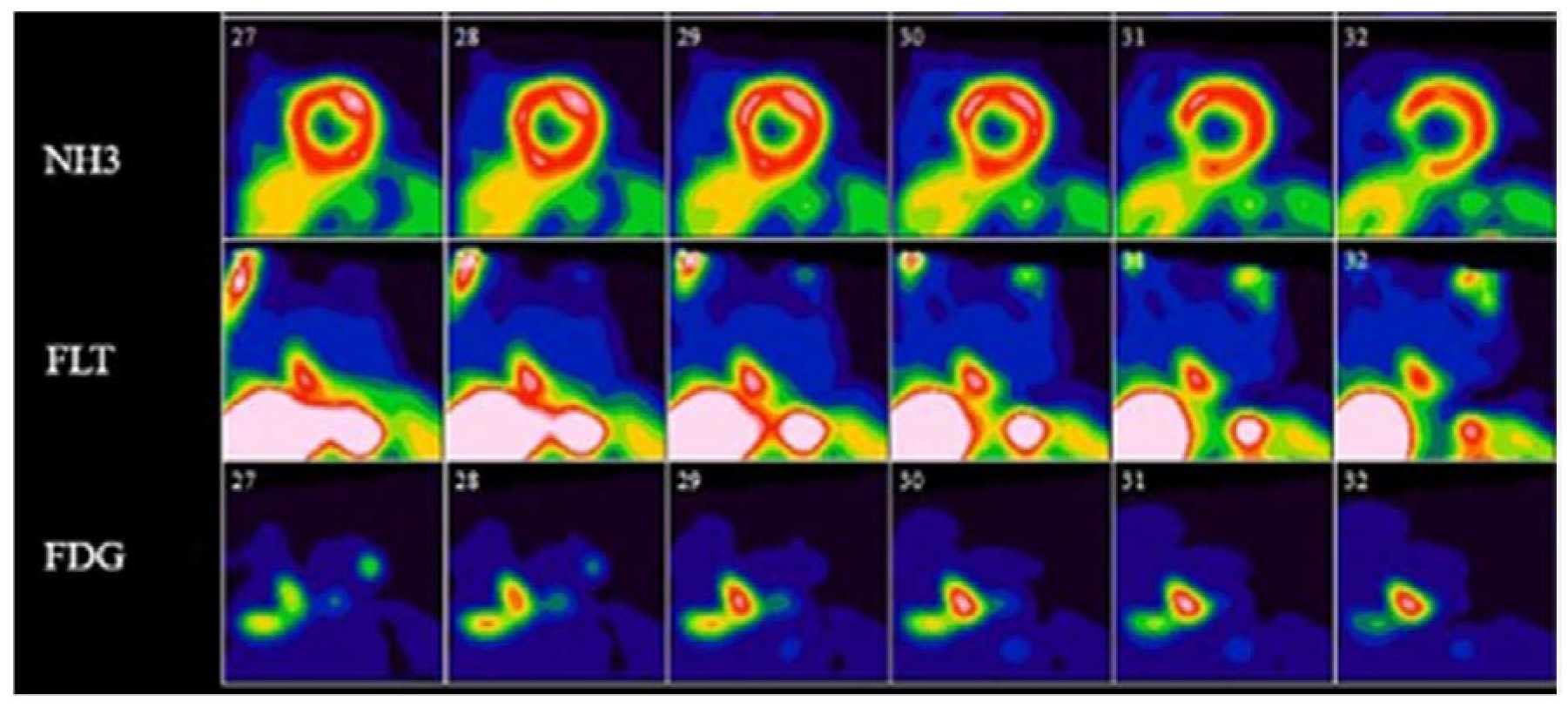

- Norikane, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Maeda, Y.; Noma, T.; Dobashi, H.; Nishiyama, Y. Comparative evaluation of 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG for detecting cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement in patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2017, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, P.; Pelletier-Galarneau, M.; Juneau, D.; Leung, E.; Nery, P.; Dekemp, R.; Beanlands, R.; Birnie, D. FLT-PET for the assessment of systemic sarcoidosis including cardiac and CNS involvement: A prospective study with comparison to FDG-PET. EJNMMI Res. 2020, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, P.; Pelletier-Galarneau, M.; Juneau, D.; Leung, E.; Nery, P.B.; de Kemp, R.; Beanlands, R.; Birnie, D. Imaging cardiac sarcoidosis with FLT-PET compared with FDG/Perfusion-PET. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 2280–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabria, F.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Schillaci, O. 18F-Choline PET/CT Pitfalls in Image Interpretation: An update on 300 examined patients with prostate cancer. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2014, 39, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensi, M.; Giacomuzzi, F.; Magli, A.; Geatti, O. In prostate cancer (PC) patients, PET-CT-18F-choline (FC) can incidentally discover unrelated diseases: Our experience in 573 cases. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1663. [Google Scholar]

- Takesh, M.; Haberkorn, U.; Strauss, L.; Roumia, S.; Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss, A. Incidental detection and monitoring of spontaneous recovery of sarcoidosis via fluorine-18-fluoroethyl-choline positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Hell. J. Nucl. Med. 2012, 15, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Minamimoto, R.; Hotta, M.; Hiroe, M.; Awaya, T.; Nakajima, K.; Okazaki, O.; Yamashita, H.; Kaneko, H.; Hiroi, Y. Proliferation imaging with 11C-4DST PET/CT for the evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis, compared with FDG-PET/CT given a long fasting preparation protocol. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, M.; Minamimoto, R.; Kubota, S.; Awaya, T.; Hiroi, Y. 11C-4DST PET/CT imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis: Comparison with 18F-FDG and cardiac MRI. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2018, 43, 458–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasey, J.S.; Koh, W.J.; Evans, M.L.; Peterson, L.M.; Lewellen, T.K.; Graham, M.M.; Krohn, K.A. Quantifying regional hypoxia in human tumors with positron emission tomography of [18F]fluoromisonidazole: A pretherapy study of 37 patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1996, 36, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.V.; Cerqueira, M.D.; Caldwell, J.H.; Rasey, J.S.; Embree, L.; Krohn, K.A. Fluoromisonidazole: A metabolic marker of myocyte hypoxia. Circ. Res. 1990, 67, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapman, J.D.; Franko, A.J.; Sharplin, J. A marker for hypoxic cells in tumours with potential clinical applicability. Br. J. Cancer 1981, 43, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmore, G.F.; Varghese, A.J. The biological properties of reduced nitroheterocyclics and possible underlying biochemical mechanisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1986, 35, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, W.J.; Kiszałkiewicz, J.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D.; Górski, P.; Antczak, A.; Migdalska-Sęk, M.; Górski, W.; Czarnecka, K.H.; Domańska, D.; Nawrot, E.; et al. Expression of HIF-1A/VEGF/ING-4 Axis in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 866, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, S.; Naya, M.; Manabe, O.; Hirata, K.; Ohira, H.; Aikawa, T.; Koyanagawa, K.; Magota, K.; Tsujino, I.; Anzai, T.; et al. 18F-FMISO PET/CT detects hypoxic lesions of cardiac and extra-cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhajosula, S. 18F-Labeled Positron Emission Tomographic Radiopharmaceuticals in Oncology: An Overview of Radiochemistry and Mechanisms of Tumor Localization. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2007, 37, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silvola, J.M.; Saraste, A.; Forsback, S.; Laine, V.J.O.; Saukko, P.; Heinonen, S.E.; Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Roivainen, A.; Knuuti, J. Detection of hypoxia by [18F]EF5 in ath-erosclerotic plaques in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1011–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peeters, S.G.; Zegers, C.M.; Lieuwes, N.G.; van Elmpt, W.; Eriksson, J.; van Dongen, G.A.; Dubois, L.; Lambin, P. A comparative study of the hypoxia PET tracers [18F]HX4, [18F]FAZA, and [18F]FMISO in a preclinical tumor model. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 91, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamada, Y.; Uchida, Y.; Tatsumi, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kimura, H.; Kitahara, H.; Kuriyama, T. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose and carbon-11-methionine evaluation of lymphadenopathy in sarcoidosis. J. Nucl. Med. 1998, 39, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hain, S.; Beggs, A. C–11 methionine uptake in granulomatous disease. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2004, 29, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, D.; Jacobs, M.; Mantil, J. Combined C-11 methionine and F-18 FDG PET imaging in a case of neurosarcoidosis. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2006, 31, 373–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maya, Y.; Werner, R.A.; Schütz, C.; Wakabayashi, H.; Samnick, S.; Lapa, C.; Zechmeister, C.; Jahns, R.; Jahns, V.; Higuchi, T. 11C-methionine PET of myocardial inflammation in a rat model of experimental autoimmune myocarditis. J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salvatore, P.; Pagliarulo, C.; Colicchio, R.; Napoli, C. CXCR4-CXCL12-dependent inflammatory network and endothelial progenitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 3019–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doring, Y.; Pawig, L.; Weber, C.; Enoels, H. The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wester, H.J.; Keller, U.; Schottelius, M.; Beer, A.; Philipp-Abbrederis, K.; Hoffmann, F.; Šimeček, J.; Gerngross, C.; Lassmann, M.; Herrmann, K.; et al. Disclosing the CXCR4 expression in lymphoproliferative diseases by targeted molecular imaging. Theranostics 2015, 5, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourni, E.; Demmer, O.; Schottelius, M.; D’Alessandria, C.; Schulz, S.; Dijkgraaf, I.; Schumacher, U.; Schwaiger, M.; Kessler, H.; Wester, H.-J. PET of CXCR4 expression by a 68Ga-labeled highly specific targeted contrast agent. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weiberg, D.; Thackeray, J.T.; Daum, G.; Sohns, J.S.; Kropf, S.; Wester, H.-J.; Ross, T.L.; Bengel, F.; Derlin, T. Clinical molecular imaging of chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in atherosclerotic plaque using 68Ga-pentixafor PET: Correlation with Cardiovascular risk factors and calcified plaque burden. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thackeray, J.T.; Derlin, T.; Haghikia, A.; Napp, L.C.; Wang, Y.; Ross, T.; Schäfer, A.; Tillmanns, J.; Wester, H.J.; Wollert, K.C.; et al. Molecular imaging of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 after acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reiter, T.; Kircher, M.; Schirbel, A.; Werner, R.A.; Kropf, S.; Ertl, G.; Buck, A.K.; Wester, H.-J.; Bauer, W.; Lapa, C. Imaging of C-X-C motif chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression after myocardial infarction with [68Ga]pentixafor-PET/CT in correlation with cardiac MRI. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 1541–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.A.; Rajchl, M.; Butler, J.; Thompson, R.T.; Prato, F.S.; Wisenberg, G. Active cardiac sarcoidosis: First clinical experience of simultaneous positron emission tomography-magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of cardiac disease. Circulation 2013, 127, e639–e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, M.J.; Kovell, L.; Kasper, E.K.; Pomper, M.G.; Moller, D.R.; Solnes, L.; Chen, E.S.; Schindler, T.H. Myocardial blood flow and inflammatory cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Proposed Agent | Example(s) | Mechanism | Production | Half-Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiolabeled somatostatin analog | 68Ga-DOTATATE; 68Ga-DOTANOC; 68Ga-DOTATOC | Targets multinucleated cells and activated macrophages that express somatostatin receptor (SSTR) 2, which is not present on normal cardiac myocytes. | Generator | 68 min |

| Radiolabeled thymidine analogs | 3′-deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine (18F-FLT); 4′-[methyl-11C]-thiothymidine (4DST) | 18F-FLT is trapped intracellularly by the activity of thymidine kinase 1, which has been shown to accumulate in granulomas with proliferative inflammation. 4′-[methyl-11C]-thiothymidine (4DST) is incorporated into the DNA of proliferating cells. | Cyclotron | 110 min |

| Radiolabeled choline analogs | 11C-choline; 18F-choline; 18F-fluoroethyl-choline | These analogs are taken up in the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, a cell membrane component. | Cyclotron | 20 min |

| Radiolabeled nitroimidazoles | 18F-fluoromisonidazole (FMISO) | Localizes to areas with upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor, which has been shown to be overexpressed in sarcoid granulomas. | Cyclotron | 110 min |

| Radiolabeled amino acid compounds | 11C-methionine | Increased uptake in areas of enhanced amino acid metabolism, such as areas of inflammation. | Cyclotron | 20 min |

| Radiolabeled CXCR4 receptor ligand | 68Ga-pentixafor | High affinity for CXCR4 receptor which has increased expression in areas of inflammation. | Generator | 68 min |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saric, P.; Young, K.A.; Rodriguez-Porcel, M.; Chareonthaitawee, P. PET Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Narrative Review with Focus on Novel PET Tracers. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121286

Saric P, Young KA, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Chareonthaitawee P. PET Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Narrative Review with Focus on Novel PET Tracers. Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(12):1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121286

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaric, Petar, Kathleen A. Young, Martin Rodriguez-Porcel, and Panithaya Chareonthaitawee. 2021. "PET Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Narrative Review with Focus on Novel PET Tracers" Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 12: 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121286

APA StyleSaric, P., Young, K. A., Rodriguez-Porcel, M., & Chareonthaitawee, P. (2021). PET Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis: A Narrative Review with Focus on Novel PET Tracers. Pharmaceuticals, 14(12), 1286. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14121286