Guest-Mediated Reversal of the Tumbling Process in Phosphorus-Dendritic Compounds Containing β-Cyclodextrin Units: An NMR Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization

2.2. Availability of the βCD Cavities in P3N3-[O-C6H4-O-(CH2)3-βCD]6 (I)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Notes

3.2. Characterization

3.2.1. NMR Experiments

3.2.2. Characterization of P3N3-[O-C6H4-O-(CH2)n-βCD]6 (n = 3 or 4) in D2O

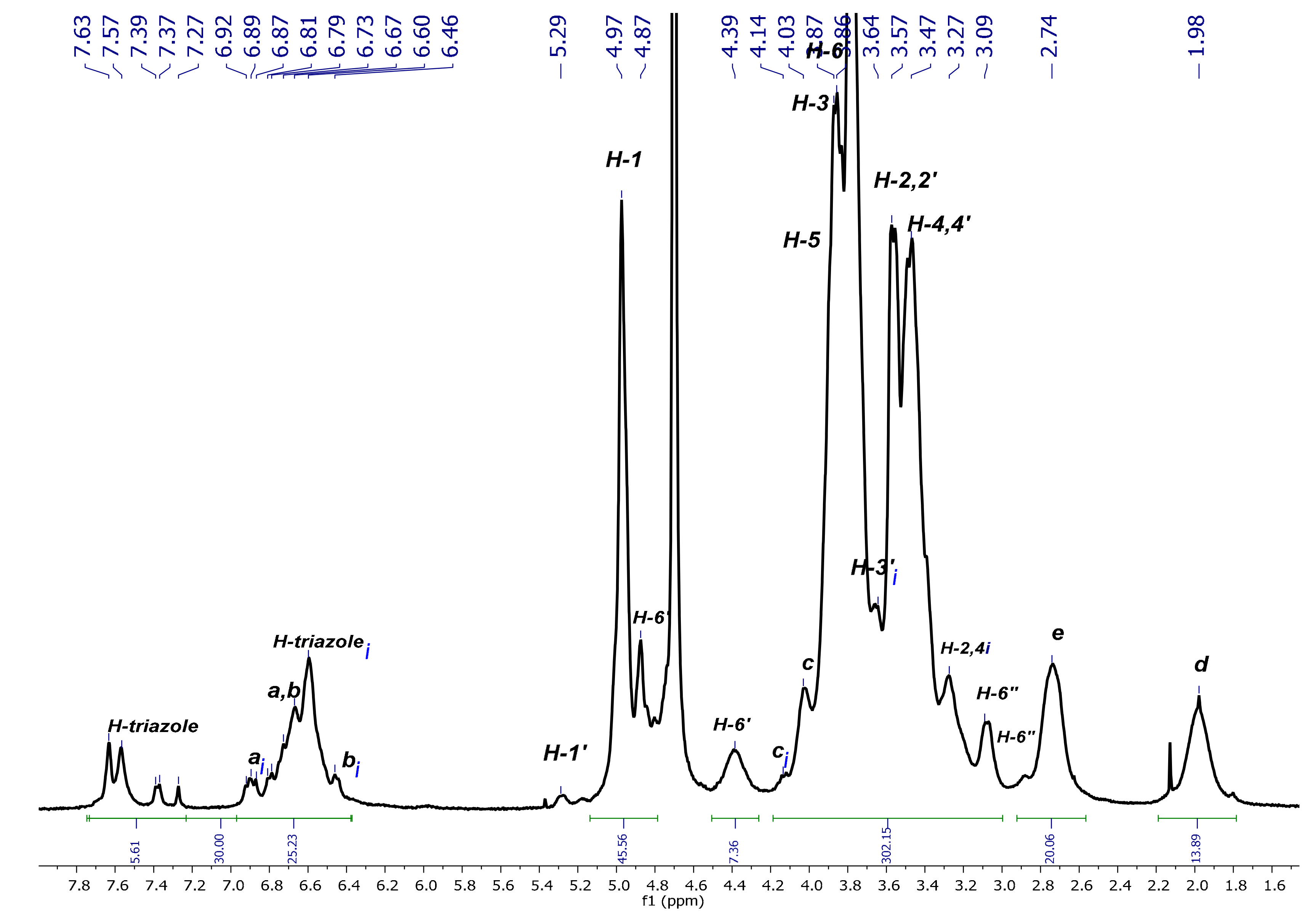

P3N3-[O-C6H4-O-(CH2)3-βCD]6

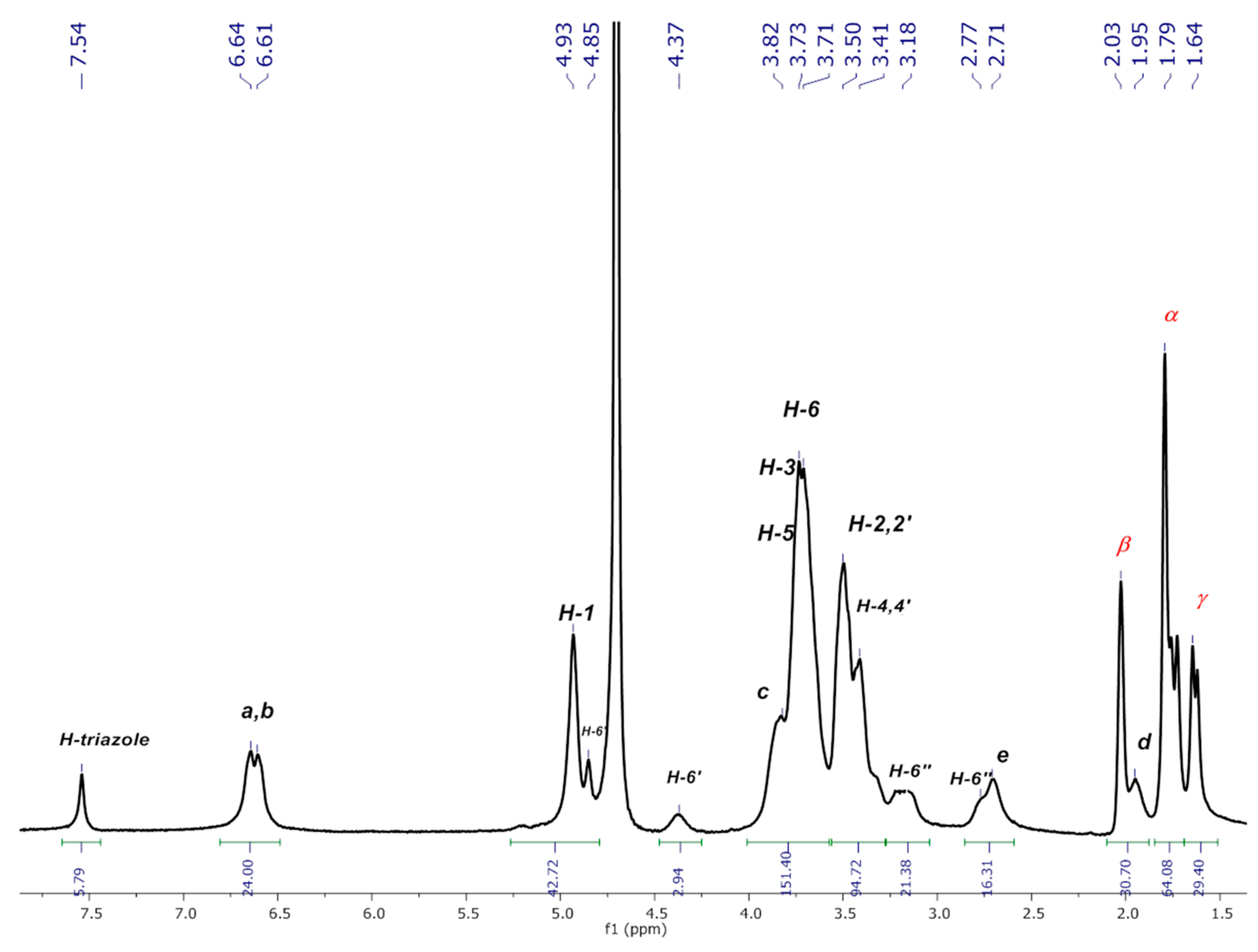

P3N3-[O-C6H4-O-(CH2)4-βCD]6

3.2.3. Job Plot Method

3.2.4. Formation of Inclusion Complexes between P3N3-[O-C6H4-O-(CH2)n-βCD]6 (n = 3 or 4) and AdCOOH

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caminade, A.M. Inorganic dendrimers: Recent advances for catalysis, nanomaterials, and nanomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5174–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminade, A.M. Phosphorus dendrimers as nanotools against cancers. Molecules 2020, 25, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majoral, J.P.; Caminade, A.M. Dendrimers Containing Heteroatoms (Si, P, B, Ge, or Bi). Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 845–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminade, A.M.; Moineau-Chane Ching, K.I.; Delavaux-Nicot, B. The Usefulness of Trivalent Phosphorus for the Synthesis of Dendrimers. Molecules 2021, 26, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.X.; Shi, X.; Mignani, S.; Caminade, A.M.; Majoral, J.P. Cyclotriphosphazene core-based dendrimers for biomedical applications: An update on recent advances. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Brahmi, N.; Mignani, S.M.; Caron, J.; El Kazzouli, S.; Bousmina, M.M.; Caminade, A.M.; Cresteil, T.; Majoral, J.P. Investigations on dendrimer space reveal solid and liquid tumor growth-inhibition by original phosphorus-based dendrimers and the corresponding monomers and dendrons with ethacrynic acid motifs. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 3915–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminade, A.M.; Maraval, V.; Laurent, R.; Turrin, C.O.; Sutra, P.; Leclaire, J.; Griffe, L.; Marchand, P.; Baudoin-Dehoux, C.; Rebout, C.; et al. Phosphorus dendrimers: From synthesis to applications. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2003, 6, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mela, I.; Kaminski, C.F. Nano-vehicles give new lease of life to existing antimicrobials. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 4, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Gupta, U.; Jain, N.K. Surface-engineered dendrimers: A solution for toxicity issues. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. 2009, 20, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Namazi, H. Advances in development of the dendrimers having natural saccharides in their structure for efficient and controlled drug delivery applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 148, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arima, H.; Motoyama, K. Recent findings concerning PAMAM dendrimer conjugates with cyclodextrins as carriers of DNA and RNA. Sensors 2009, 9, 6346–6361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arima, H.; Motoyama, K.; Higashi, T. Sugar-appended polyamidoamine dendrimer conjugates with cyclodextrins as cell-specific non-viral vectors. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorroza-Martínez, K.; González Méndez, I.; Martínez-Serrano, R.D.; Solano, J.D.; Ruiu, A.; Illescas, J.; Zhu, X.X.; Rivera, E. Efficient modification of PAMAM G1 dendrimer surface with β-cyclodextrin units by CuAAC: Impact on the water solubility and cytotoxicity. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 25557–25566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorroza-Martínez, K.; González-Méndez, I.; Vonlanthen, M.; Moineau-Chane Ching, K.I.; Caminade, A.M.; Illescas, J.; Rivera, E. First class of phosphorus dendritic compounds containing β-cyclodextrin units in the periphery prepared by CuAAC. Molecules 2020, 25, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Méndez, I.; Hameau, A.; Laurent, R.; Bijani, C.; Bourdon, V.; Caminade, A.M.; Rivera, E.; Moineau-Chane Ching, K.I. β-Cyclodextrin PAMAM Dendrimer: How to Overcome the Tumbling Process for Getting Fully Available Host Cavities. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, T.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Q.; Lin, S.; Liu, C.; Han, X. Research Progress on Synthesis and Application of Cyclodextrin polymers. Molecules 2021, 26, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legros, V.; Vanhaverbeke, C.; Souard, F.; Len, C.; Désiré, J. β-Cyclodextrin-glycerol dimers: Synthesis and NMR conformational analysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2583–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menuel, S.; Azaroual, N.; Landy, D.; Six, N.; Hapiot, F.; Monflier, E. Unusual inversion phenomenon of β-cyclodextrin dimers in water. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 3949–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, Y.; Fukui, Y.; Otsubo, M.; Hamada, N.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yamamoto, H.; Harada, A. Emission properties of cyclodextrin dimers linked with perylene diimide - effect of cyclodextrin tumbling. Polym. J. 2012, 44, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamauchi, K.; Miyawaki, A.; Takashima, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Harada, A. Switching from altro-α-Cyclodextrin dimer to pseudo[1]rotaxane dimer through tumbling. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1284–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourer, M.; Hapiot, F.; Monflier, E.; Menuel, S. Click chemistry as an efficient tool to access β-cyclodextrin dimers. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 7159–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourer, M.; Hapiot, F.; Tilloy, S.; Monflier, E.; Menuel, S. Easily accessible mono- and polytopic β-cyclodextrin hosts by click chemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 1, 5723–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ke, C.F.; Zhang, H.Y.; Cui, J.; Ding, F. Complexation-induced transition of nanorod to network aggregates: Alternate porphyrin and cyclodextrin arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho Miranda, G.; Ramos e Santos, V.O.; Reis Bessa, J.; Teles, Y.C.F.; Yahouédéhou, S.C.M.A.; Souza Goncalves, M.; Ribeiro-Filho, J. Inclusion complexes of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with cyclodextrins: A systematic review. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchêne, D.; Bochot, A. Thirty years with cyclodextrins. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 514, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, G.; Boy, R.; Gupta, B.S.; Tonelli, A.E. Analytical techniques for characterizing cyclodextrins and their inclusion complexes with large and small molecular weight guest molecules. Polym. Test. 2017, 62, 402–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelczak, M.; Liz-Marzán, L.M.; Klajn, R. Stimuli-responsive self-assembly of nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1342–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitesides, G.M.; Grzybowski, B. Self-assembly at all scales. Science 2002, 295, 2418–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szejtli, J. Past, present, and future of cyclodextrin research. Pure Appl. Chem. 2004, 76, 1825–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paolino, M.; Ennen, F.; Lamponi, S.; Cernescu, M.; Voit, B.; Cappelli, A.; Appelhans, D.; Komber, H. Cyclodextrin-adamantane host-guest interactions on the surface of biocompatible adamantyl-modified glycodendrimers. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 3215–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftink, M.R.; Andy, M.L.; Bystrom, K.; Perlmutter, H.D.; Kristol, D.S. Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes: Studies of the Variation in the Size of Alicyclic Guests. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 6765–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.F.; Rogach, A.L.; Wong, W.T. Chemistry and engineering of cyclodextrins for molecular imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6379–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Chen, X. Host–guest chemistry in supramolecular theranostics. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3041–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challa, R.; Ahuja, A.; Ali, J.; Khar, R.K. Cyclodextrins in drug delivery: An updated review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2005, 6, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belica, S.; Sadowska, M.; Stȩpniak, A.; Graca, A.; Pałecz, B. Enthalpy of solution of α- And β-cyclodextrin in water and in some organic solvents. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2014, 69, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikata, T.; Takahashi, R.; Onji, T.; Satokawa, Y.; Harada, A. Solvation and dynamic behavior of cyclodextrins in dimethyl sulfoxide solution. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 18112–18114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daschakraborty, S. How do glycerol and dimethyl sulphoxide affect local tetrahedral structure of water around a nonpolar solute at low temperature? Importance of preferential interaction. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uria-Canseco, E.; Perez-Casas, S.; Navarrete-Vázquez, G. Thermodynamic characterization of the inclusion complexes formation between antidiabetic new drugs and cyclodextrins. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2019, 129, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potier, J.; Menuel, S.; Azaroual, N.; Monflier, E.; Hapiot, F. Limits of the inversion phenomenon in triazolyl-substituted β-cyclodextrin dimers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, D.; Rau, D.C.; Parsegian, V.A. Solutes probe hydration in specific association of cyclodextrin and adamantane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2184–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodell, C.B.; Mealy, J.E.; Burdick, J.A. Supramolecular Guest-Host Interactions for the Preparation of Biomedical Materials. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015, 26, 2279–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Méndez, I.; Aguayo-Ortiz, R.; Sorroza-Martínez, K.; Solano, J.D.; Porcu, P.; Rivera, E.; Dominguez, L. Conformational analysis by NMR and molecular dynamics of adamantane-doxorubicin prodrugs and their assemblies with β-cyclodextrin: A focus on the design of platforms for controlled drug delivery. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Luo, Q.; Li, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhu, W. Injectable doxorubicin-loaded hydrogels based on dendron-like β-cyclodextrin–poly(ethylene glycol) conjugates. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorroza-Martínez, K.; González-Méndez, I.; Vonlanthen, M.; Cuétara-Guadarrama, F.; Illescas, J.; Zhu, X.X.; Rivera, E. Guest-Mediated Reversal of the Tumbling Process in Phosphorus-Dendritic Compounds Containing β-Cyclodextrin Units: An NMR Study. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060556

Sorroza-Martínez K, González-Méndez I, Vonlanthen M, Cuétara-Guadarrama F, Illescas J, Zhu XX, Rivera E. Guest-Mediated Reversal of the Tumbling Process in Phosphorus-Dendritic Compounds Containing β-Cyclodextrin Units: An NMR Study. Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(6):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060556

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorroza-Martínez, Kendra, Israel González-Méndez, Mireille Vonlanthen, Fabián Cuétara-Guadarrama, Javier Illescas, Xiao Xia Zhu, and Ernesto Rivera. 2021. "Guest-Mediated Reversal of the Tumbling Process in Phosphorus-Dendritic Compounds Containing β-Cyclodextrin Units: An NMR Study" Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 6: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060556

APA StyleSorroza-Martínez, K., González-Méndez, I., Vonlanthen, M., Cuétara-Guadarrama, F., Illescas, J., Zhu, X. X., & Rivera, E. (2021). Guest-Mediated Reversal of the Tumbling Process in Phosphorus-Dendritic Compounds Containing β-Cyclodextrin Units: An NMR Study. Pharmaceuticals, 14(6), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14060556