Enhancing the Antipsychotic Effect of Risperidone by Increasing Its Binding Affinity to Serotonin Receptor via Picric Acid: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

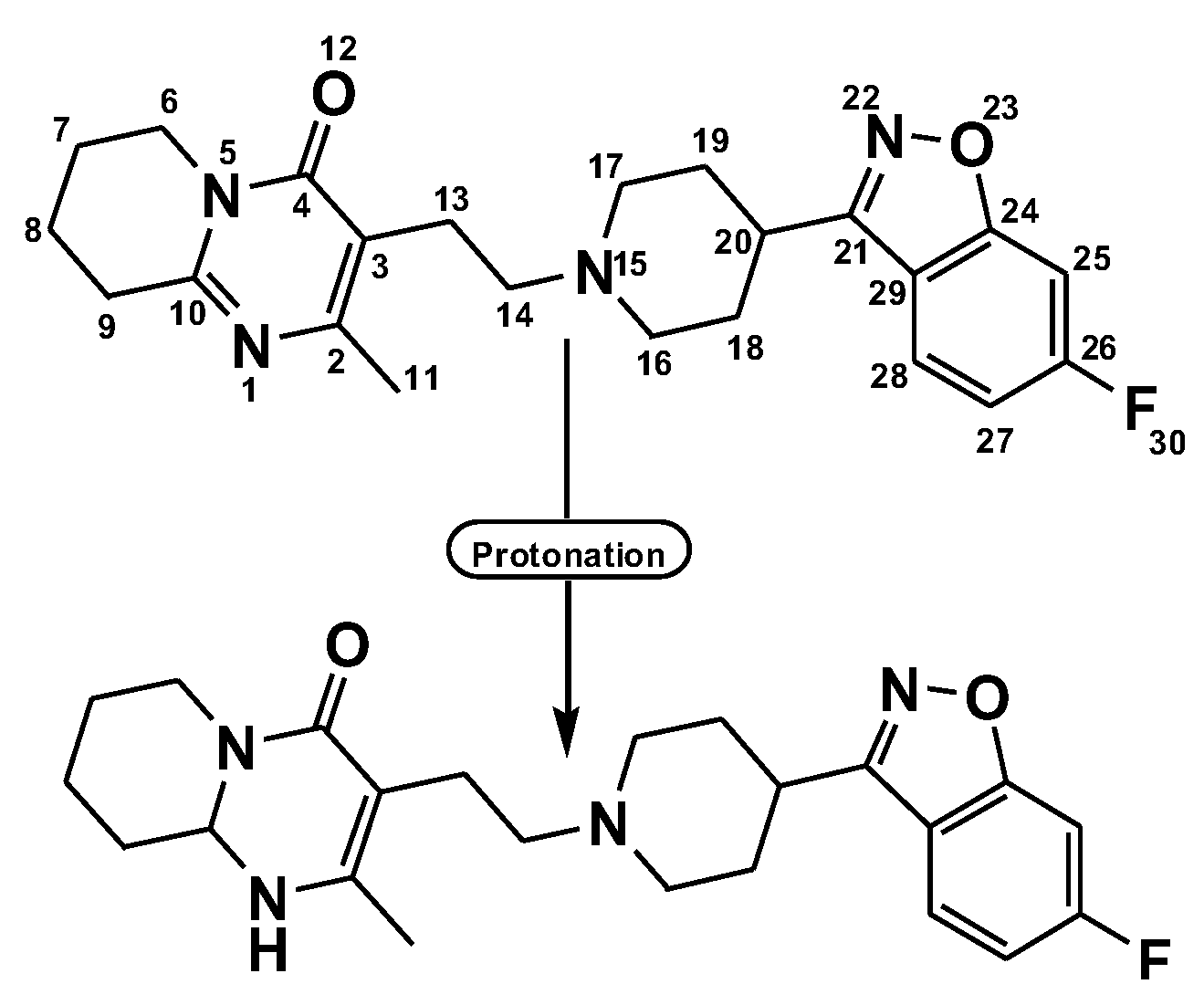

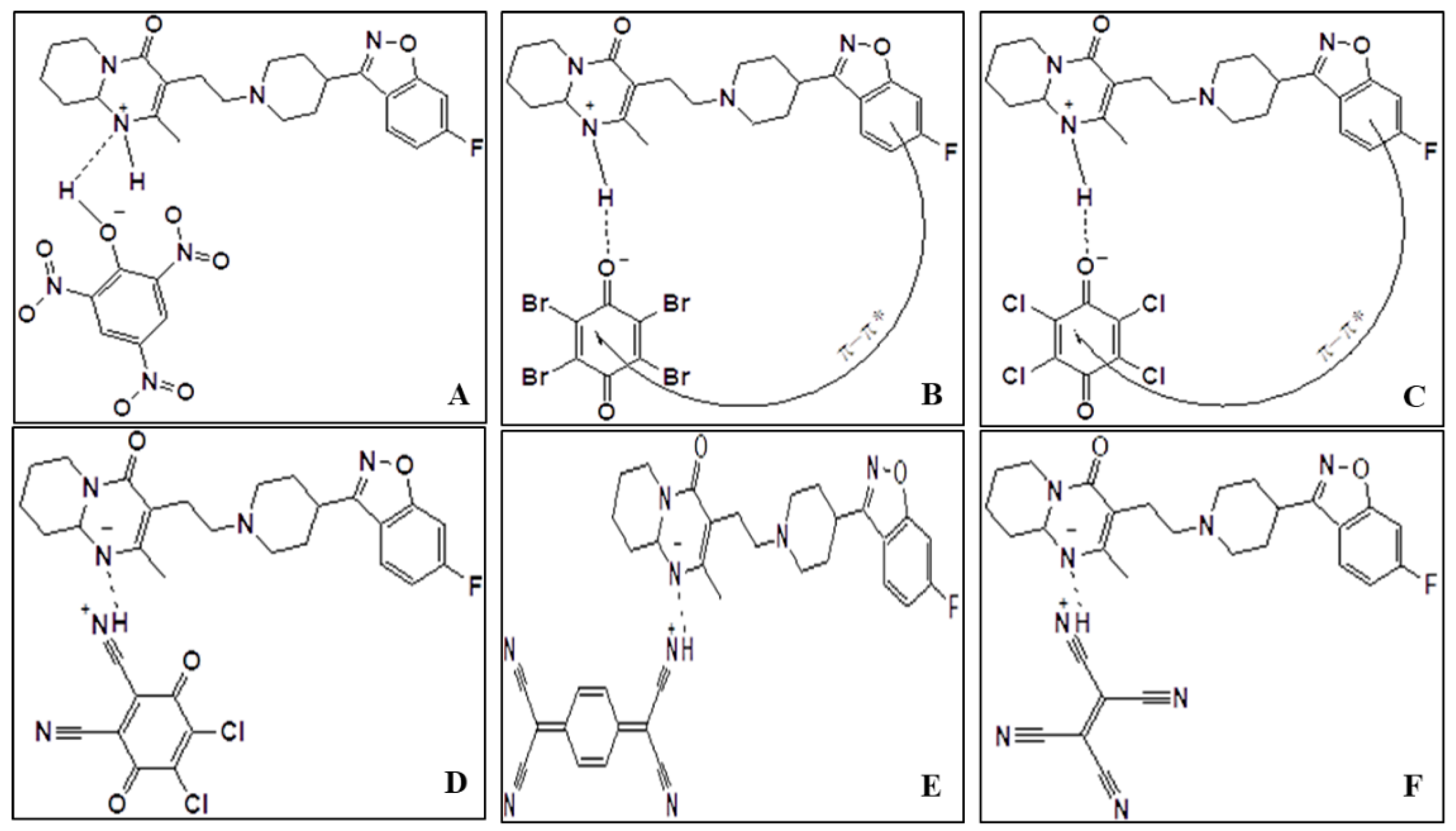

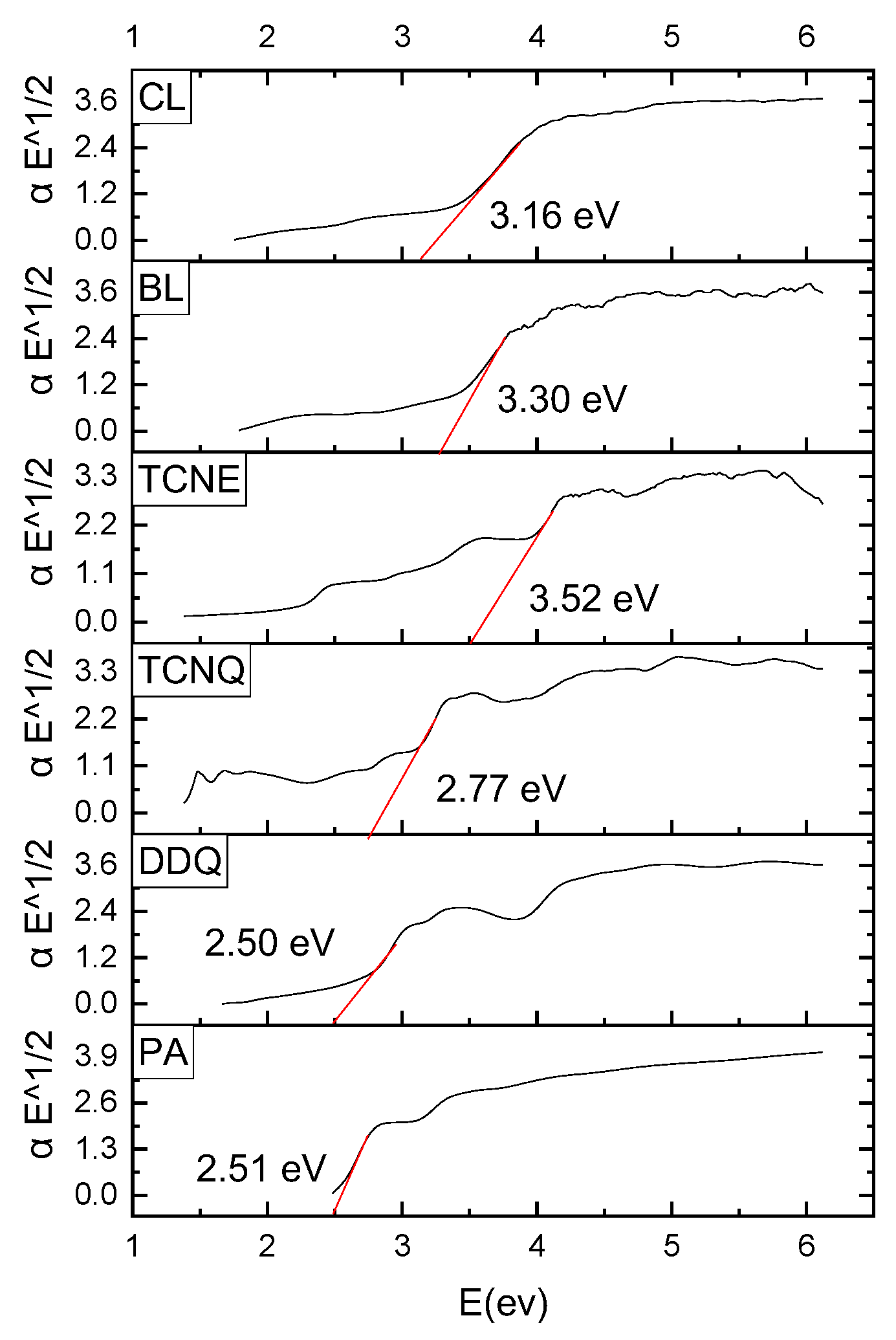

2.1. Preface of Six-Risperidone Solid Charge Transfer Complexes

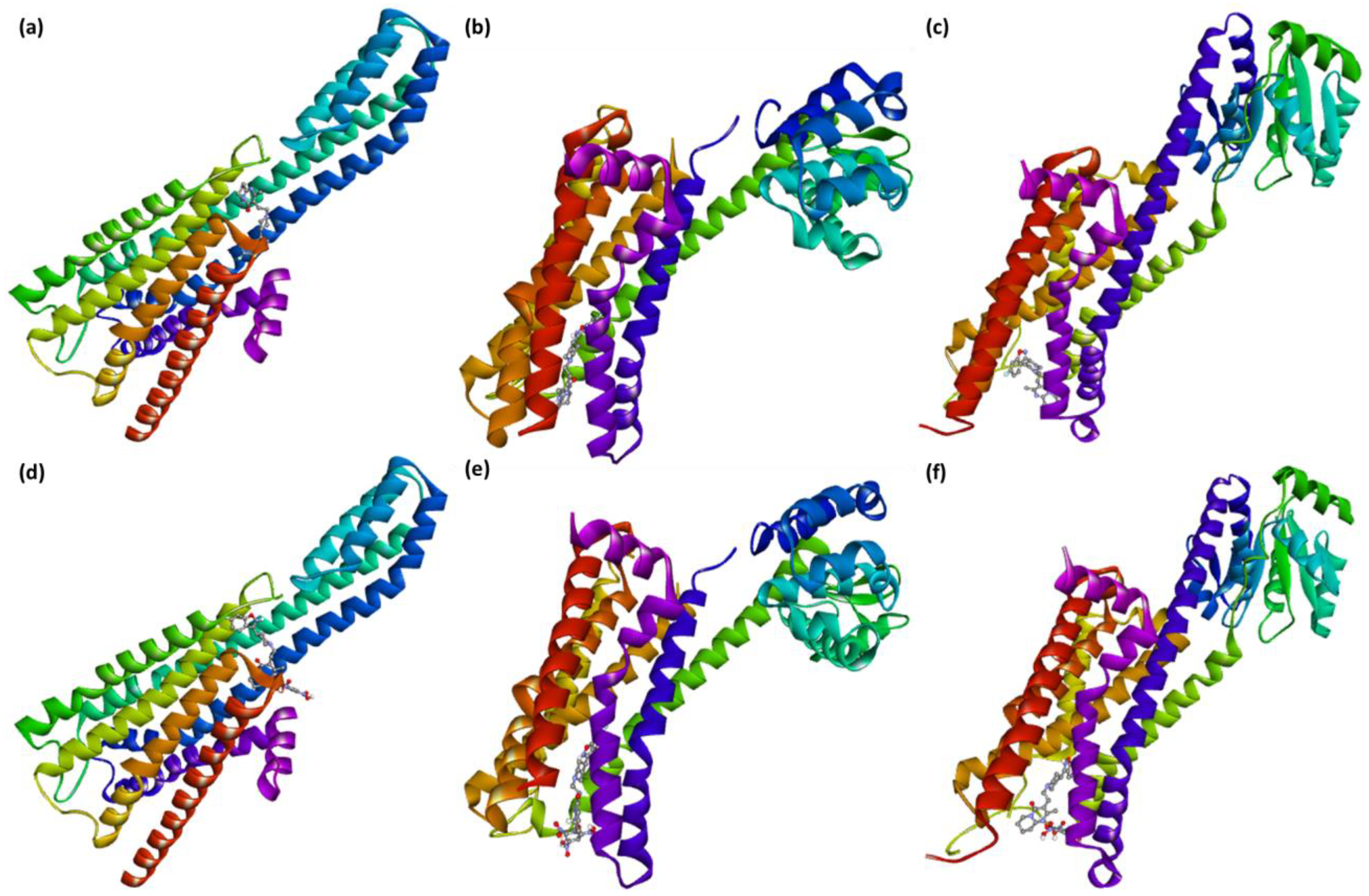

2.2. Molecular Docking

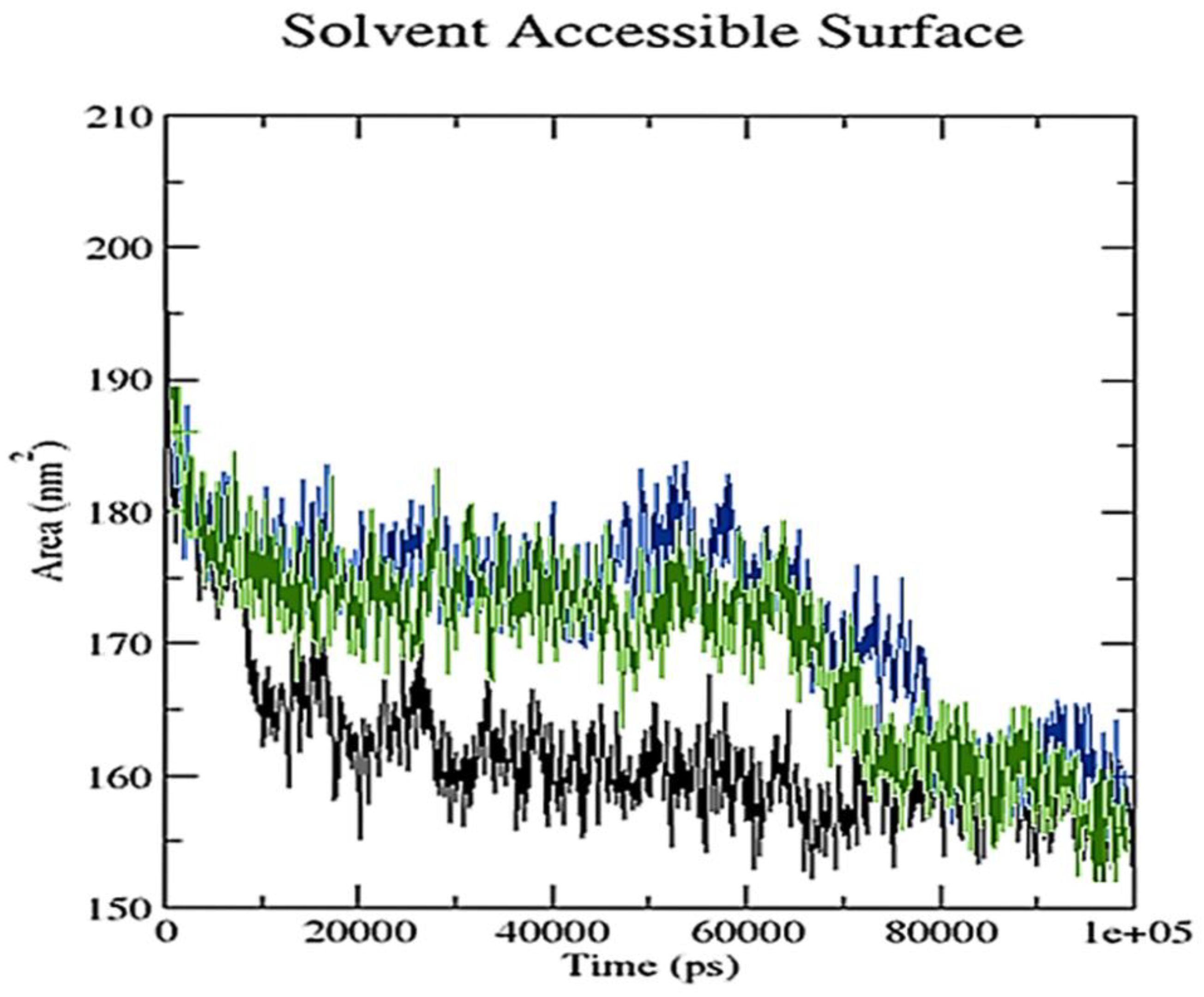

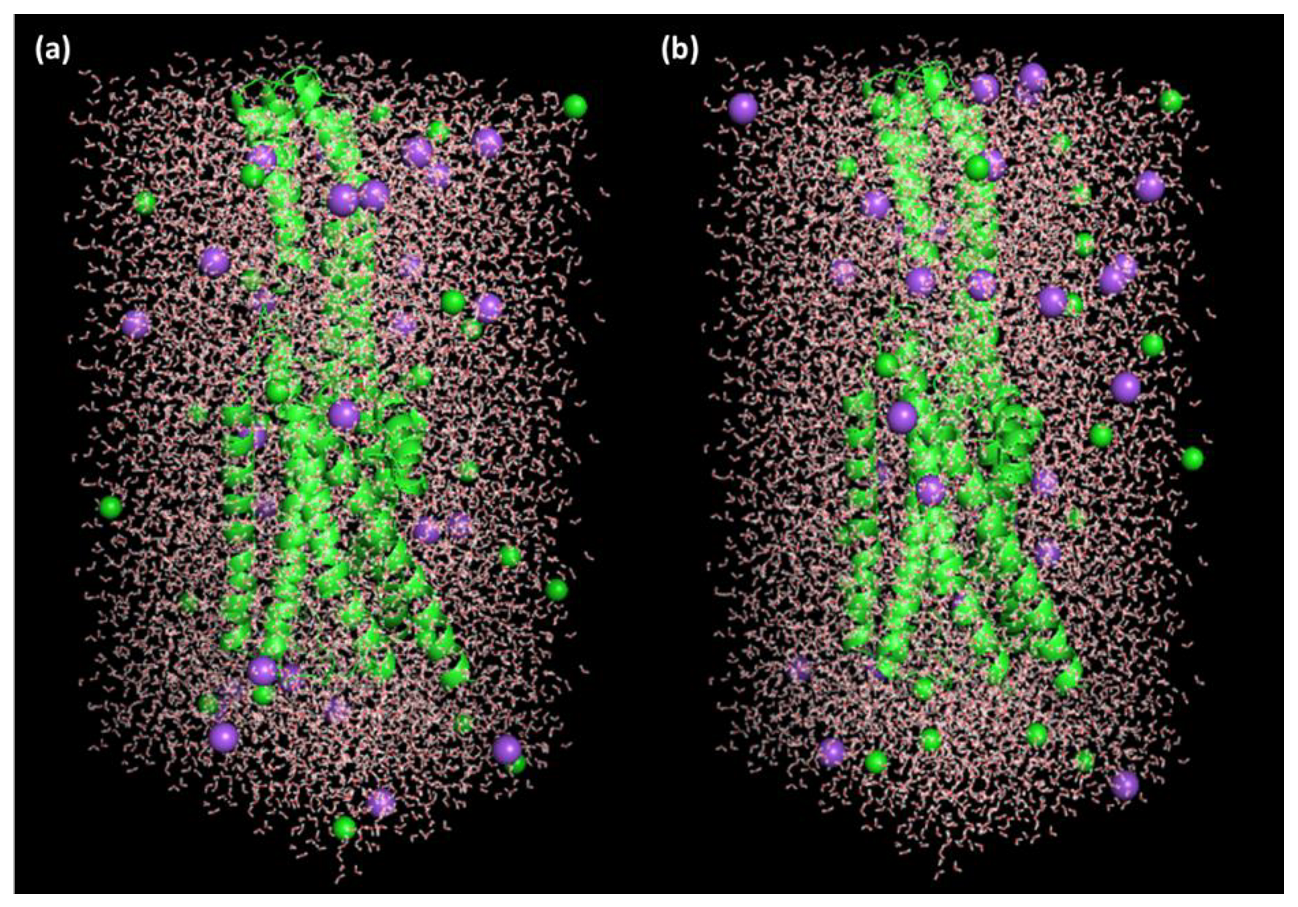

2.3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of Six Ris Charge Transfer Complexes

3.2. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Madaan, V.; Bestha, D.P.; Kolli, V.; Jauhari, S.; Burket, R.C. Clinical utility of the risperidone formulations in the management of schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2011, 7, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shen, W.W. A history of antipsychotic drug development. Compr. Psychiatry 1999, 40, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopko, T.C.; Lindsley, C.W. Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Risperidone. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puangpetch, A.; Vanwong, N.; Nuntamool, N.; Hongkaew, Y.; Chamnanphon, M.; Sukasem, C. CYP2D6 polymorphisms and their influence on risperidone treatment. Pharmgenomics Pers. Med. 2016, 9, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Upthegrove, R.; Marwaha, S.; Birchwood, M. Depression and schizophrenia: Cause, consequence, or trans-diagnostic issue? Schizophr. Bull. 2017, 43, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seeman, P. Are dopamine D2 receptors out of control in psychosis? Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 46, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, V.; Venkatesan, V.; Ramasamy, B. Role of serotonin transporter and receptor gene polymorphisms in treatment response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 6, e2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozielska, M.; Johnson, M.; Pilla Reddy, V.; Vermeulen, A.; Li, C.; Grimwood, S.; De Greef, R.; Groothuis, G.M.M.; Danhof, M.; Proost, J.H. Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Modeling of the D2 and 5-HT2A Receptor Occupancy of Risperidone and Paliperidone in Rats. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirabzadeh, A.; Kimiaghalam, P.; Fadai, F.; Samiei, M.; Daneshmand, R. The Therapeutic Effectiveness of Risperidone on Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia in Comparison with Haloperidol: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Nord, M.; Farde, L. Antipsychotic occupancy of dopamine receptors in schizophrenia. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2011, 17, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selent, J.; López, L.; Sanz, F.; Pastor, M. Multi-Receptor Binding Profile of Clozapine and Olanzapine: A Structural Study Based on the New β2 Adrenergic Receptor Template. ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 1194–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Zaria, M.E. Spectrophotometric study of the charge transfer complexation of some porphyrin derivatives as electron donors with tetracyanoethylene. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 69, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refat, M.S.; El-Metwally, N.M. Investigation of charge transfer complexes formed between 3,3′-dimethylbenzidine (o-toluidine) donor and DDQ, p-chloranil and TCNQ as π-acceptors. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pandeeswaran, M.; Elango, K.P. Spectroscopic studies on the interaction of cimetidine drug with biologically significant σ- and π-acceptors. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010, 75, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refat, M.S.; El-Korashy, S.A.; El-Deen, I.M.; El-Sayed, S.M. Charge-transfer complexes of sulfamethoxazole drug with different classes of acceptors. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 980, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldaroti, H.H.; Gadir, S.A.; Refat, M.S.; Adam, A.M.A. Spectroscopic investigations of the charge-transfer interaction between the drug reserpine and different acceptors: Towards understanding of drug–receptor mechanism. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 115, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolkovas, A. Essentials of Medicinal Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Horino, K.; Komura, T.; Murata, K. Photovoltaic Properties of Porphyrin Thin Films Mixed with o-Chloranil. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1993, 66, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Attia, F.M. Use of charge-transfer complex formation for the spectrophotometric determination of nortriptyline. Farmaco 2000, 55, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhokale, B.; Gautam, P.; Misra, R. Donor–acceptor perylenediimide–ferrocene conjugates: Synthesis, photophysical, and electrochemical properties. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 2352–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragani, R.; Jadhav, T.; Mobin, S.M.; Misra, R. Synthesis, structure, photophysical, and electrochemical properties of donor–acceptor ferrocenyl derivatives. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 7302–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparone, A. Spectroscopic properties of neuroleptics: IR and Raman spectra of Risperidone (Risperdal) and of its mono- and di-protonated forms. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 81, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Habeeb, A.A.; Al-Saif, F.A.; Refat, M.S. Spectroscopic and thermal investigations on the charge transfer interaction between risperidone as a schizophrenia drug with some traditional π-acceptors: Part 2. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1036, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Andre, J.J. Molecular Semiconductors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M. Optical properties of solids. Am. J. Phys. 2002, 70, 1269–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H.S.; El-Barry, A.M.A.; Yaghmour, S.; Al-Solami, T.S. Effects of γ-irradiation and heat treatment on structural, spectral and optical parameters of pyronine G (Y) thin films. J. Alloys Comp. 2009, 481, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refat, M.S. Spectroscopic and thermal investigations of charge-transfer complexes formed between sulfadoxine drug and different types of acceptors. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 985, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Lal, H.; Shakya, S.; Kabir-Ud-Din. Multispectroscopic and Computational Analysis Insight into the Interaction of Cationic Diester-Bonded Gemini Surfactants with Serine Protease α-Chymotrypsin. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 3624–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, B.; Shakya, S.; Hasan Siddique, Y. Effect of geraniol against arecoline induced toxicity in the third instar larvae of transgenic Drosophila melanogaster (hsp70-lacZ) Bg9. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2018, 29, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Islam, M.; Shakya, S.; Alam, N.; Imtiaz, S.; Islam, M.R. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial activity, molecular docking and DFT studies of proton transfer (H-bonded) complex of 8-aminoquinoline (donor) with chloranilic acid (acceptor). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Shakya, S.; Islam, M.; Khan, S.; Najnin, H. Synthesis and spectrophotometric studies of CT complex between 1,2-dimethylimidazole and picric acid in different polar solvents: Exploring antimicrobial activities and molecular (DNA) docking. Phys. Chem. Liq. 2020, 59, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufareva, I.; Abagyan, R. Methods of Protein Structure Comparison. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 857, 231–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y. A comprehensive assessment of sequence-based and template-based methods for protein contact prediction. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, M.D.; Shakya, S.; Thi Vu, H.H.; Habte, L.; Ahn, J.W. Low concentrated phosphorus sorption in aqueous medium on aragonite synthesized by carbonation of seashells: Optimization, kinetics, and mechanism study. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, D.S.; Colwell, L.J.; Sheridan, R.; Hopf, T.A.; Pagnani, A.; Zecchina, R.; Sander, C. Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kavitha, R.; Nirmala, S.; Nithyabalaji, R.; Sribalan, R. Biological evaluation, molecular docking and DFT studies of charge transfer complexes of quinaldic acid with heterocyclic carboxylic acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1204, 127508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjani, S.; Nirmala, C.B.; Rajkumar, P.; Serdaroğlu, G.; Jayaprakash, N.; Venkatachalam, K. Synthesis, characterization, biological and DFT studies of charge-transfer complexes of antihyperlipidemic drug atorvastatin calcium with Iodine, Chloranil, and DDQ. J. Mol. Liqui. 2022, 346, 117862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farde, L.; Nordström, A.L.; Wiesel, F.A.; Pauli, S.; Halldin, C.; Sedvall, G. Positron Emission Tomographic Analysis of Central D1 and D2 Dopamine Receptor Occupancy in Patients Treated with Classical Neuroleptics and Clozapine: Relation to Extrapyramidal Side Effects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1992, 49, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dallakyan, S. PyRx-python prescription v. 0.8; The Scripps Research Institute: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.H.; Li, K.M.; Lin, S.W.; Chang, M.D.T.; Jiang, T.Y.; Sun, Y.J. Crystal structures of starch binding domain from Rhizopus oryzae glucoamylase in complex with isomaltooligosaccharide: Insights into polysaccharide binding mechanism of CBM21 family. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2014, 82, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Goodsell, D.S.; Halliday, R.S.; Huey, R.; Hart, W.E.; Belew, R.K.; Olson, A.J. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, W.; He, X.; Vanommeslaeghe, K.; MacKerell, A.D. Extension of the CHARMM general force field to sulfonyl-containing compounds and its utility in biomolecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 2451–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L.; Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. JChPh 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.L. Computer simulation of liquids. J. Solut. Chem. 1989, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essmann, U.; Perera, L.; Berkowitz, M.L.; Darden, T.; Lee, H.; Pedersen, L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 103, 8577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grace. Available online: http://plasma-gate.weizmann.ac.Il/grace/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLano, L.W. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Version 2.0.2, Schrödinger, LLC. Available online: http://www.pymol.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

| S. No. | Receptor | Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) | ||||||

| Ris | [(Ris) (PA)] | [(Ris) (BL)] | [(Ris) (CL)] | [(Ris) (DDQ)] | [(Ris) (TCNQ)] | [(Ris) (TCNE)] | ||

| 1 | Serotonin | −9.6 | −11.4 | −8.5 | −9.0 | −10.5 | −10.0 | −8.6 |

| 2 | Dopamine | −8.4 | −10.6 | −9.8 | −9.9 | −10.0 | −10.5 | −8.8 |

| 3 | Adrenergic | −9.1 | −10.2 | −10.2 | −10.1 | −9.8 | −9.6 | −8.5 |

| S. No. | Receptor | Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) | Interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-Bond | Others | |||

| 1 | Serotonin | −9.6 | Arg173 | Leu325, Ala321, Val324 and Ala176 (π-Alkyl) |

| 2 | Dopamine | −8.4 | His393 | Val115, Phe389, Cys118, and Ile184 (π-Alkyl); Trp386 (π-Sigma) |

| 3 | Adrenergic | −9.1 | Tyr427 | Phe4155, Tyr405, and Leu204 (π-Alkyl) |

| S. No. | Receptor | Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) | Interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-Bond | Others | |||

| 1 | Serotonin | −11.4 | His182, Asn187, Asn384, Lys320 and Arg173 | Leu325, Ala321, Ala108 and Ala176 (π-Alkyl); Asp172 (Halogen-fluorine) |

| 2 | Dopamine | −10.6 | Thr142, Ala185, His393, and Tyr408 | Val115 and Phe389 (π-Alkyl); Trp386 (π-Sigma); Cys118 (Halogen-fluorine) |

| 3 | Adrenergic | −10.2 | Val414, Asp206, Asp131, and Ser218 | Phe398, Phe423, and Cys135 (π-Alkyl); Val132 (π-Sigma); Ser214 (Halogen-fluorine) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhomrani, M.; Alsanie, W.F.; Alamri, A.S.; Alyami, H.; Habeeballah, H.; Alkhatabi, H.A.; Felimban, R.I.; Haynes, J.M.; Shakya, S.; Raafat, B.M.; et al. Enhancing the Antipsychotic Effect of Risperidone by Increasing Its Binding Affinity to Serotonin Receptor via Picric Acid: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15030285

Alhomrani M, Alsanie WF, Alamri AS, Alyami H, Habeeballah H, Alkhatabi HA, Felimban RI, Haynes JM, Shakya S, Raafat BM, et al. Enhancing the Antipsychotic Effect of Risperidone by Increasing Its Binding Affinity to Serotonin Receptor via Picric Acid: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Pharmaceuticals. 2022; 15(3):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15030285

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhomrani, Majid, Walaa F. Alsanie, Abdulhakeem S. Alamri, Hussain Alyami, Hamza Habeeballah, Heba A. Alkhatabi, Raed I. Felimban, John M. Haynes, Sonam Shakya, Bassem M. Raafat, and et al. 2022. "Enhancing the Antipsychotic Effect of Risperidone by Increasing Its Binding Affinity to Serotonin Receptor via Picric Acid: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation" Pharmaceuticals 15, no. 3: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15030285

APA StyleAlhomrani, M., Alsanie, W. F., Alamri, A. S., Alyami, H., Habeeballah, H., Alkhatabi, H. A., Felimban, R. I., Haynes, J. M., Shakya, S., Raafat, B. M., Refat, M. S., & Gaber, A. (2022). Enhancing the Antipsychotic Effect of Risperidone by Increasing Its Binding Affinity to Serotonin Receptor via Picric Acid: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Pharmaceuticals, 15(3), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15030285