Abstract

The use of azathioprine (AZA) in human medicine dates back to research conducted in 1975 that led to the development of several drugs, including 6-mercaptopurine. In 1958, it was shown that 6-mercaptopurine decreased the production of antibodies against earlier administered antigens, raising the hypothesis of an immunomodulatory effect. AZA is a prodrug that belongs to the thiopurine group of drugs that behave as purine analogs. After absorption, it is converted into 6-mercaptopurine. Subsequently, it can be degraded through various enzymatic pathways into inactive compounds and biologically active compounds related to the mechanism of action, which has been the subject of study to evaluate a possible antiviral effect. This study aims to examine the metabolism, mechanism of action, and antiviral potential of AZA and its derivatives, exploring AZA impact on antiviral targets and adverse effects through a narrative literature review. Ultimately, the review will provide insights into the antiviral mechanism, present evidence of its in vitro effectiveness against various DNA and RNA viruses, and suggest in vivo studies to further demonstrate its antiviral effects.

1. Introduction: Brief History and Development of Azathioprine

The use of azathioprine (AZA) in human medicine dates back to research conducted in 1954 by Nobel Laureates George Herbert Hitchings and Gertrude Elion, who studied the nucleic acid metabolism in normal cells, tumoral cells, and bacterial cells, with the goal of interfering with the purine pathway to block the production of nucleotides such as adenine and guanine, thereby inhibiting DNA synthesis and cell replication [1,2]. Those early works, led to the development of drugs that are still in use in clinical practice such as allopurinol, acyclovir, trimethoprim, and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) [3]. This review details the metabolism of AZA and the mechanism of action of its derivatives as a possible antiviral therapeutic agent, and it discusses studies conducted to evaluate the antiviral effect of AZA and its derivatives on both, DNA and RNA viruses.

Mercaptopurines were primarily evaluated for the treatment of leukemia in the early 1950s. The original studies on this compound in mice showed tumor inhibition against Sarcoma 180 [4,5] and effectively inhibited the growth of adenocarcinoma EO771, Bashford carcinoma 63, carcinoma 1025, epidermoid carcinoma, among others [6]. Extensive toxicologic and pathologic studies of 6-MP were developed in mice, rats, cats, and dogs [5,7]. The first human trial developed by Burchenal et al., was published in 1953, involving the use of 6-MP in the treatment of multiple leukemias and other cancers, in children and adults, inducing good clinical and hematologic remissions and clinical improvement [8].

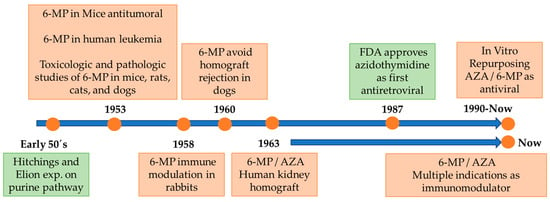

Later, Robert Schwartz in 1958 showed that treatment with 6-MP in rabbits led to a decrease in the generation of antibodies against previously administered antigens, which raised the hypothesis of an immunomodulatory effect and its use in transplants [9]. This research led to the first report of the positive effect of 6-MP on the rejection of dog kidney homograft, increasing patient survival [10], and soon to the human studies involving the use of 6-MP and azathioprine instead of irradiation in patients with kidney homografts [11] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of 6-MP/AZA development. Green boxes denote key facts not directly related to the 6-MP/AZA. See text for details.

After the identification of human retroviruses such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), research efforts were carried out to identify drugs capable of treating or preventing lethal diseases caused by viruses, and it was shown that several nucleoside analogs exhibit in vitro anti-HIV-1 activity in accordance with the development of clinical trials in 1987 [12]. It was also found that a variety of purine derivatives had antiviral potential, such as hypoxanthine (6-hydroxypurine), which has strong antitumor activity with minimal side effects. In addition, this compound is an intermediate product in the synthesis of other substituted purines, such as 6-mercaptopurine, considered an antiviral agent of the purine series and derived from AZA [13].

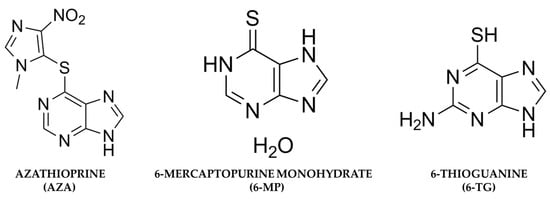

AZA is a prodrug that belongs to a group of immunosuppressive drugs called thiopurines, which behave like purine analogs. Although AZA and 6-MP (Figure 2) have been studied with the same therapeutic objective, it has also been shown that the bioavailability of AZA could be higher than that of 6-MP. When 6-MP is administered orally, it subsequently undergoes extensive catabolism by the enzyme xanthine oxidase (XO), which can be found in the liver and intestinal mucosa, and by thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT), which is present in the intestinal mucosa and methylates 6-MP into inactive metabolites, limiting its systemic bioavailability [14]. After being taken orally, AZA exhibits an approximate 88% bioavailability and undergoes rapid absorption. Around 30% of it binds to plasma proteins, and it achieves its highest serum concentration approximately two hours post-ingestion [15].

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and 6-Thioguanine.

2. Azathioprine Metabolism

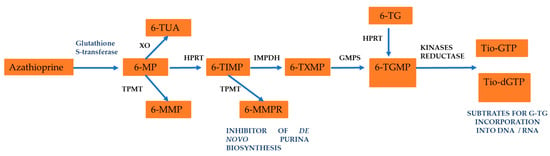

After its absorption through the in the intestinal wall of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and red blood cells, AZA is metabolized into 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) due to nonenzymatic removal of its nitroimidazole ring, which seems to be mediated by glutathione S-transferase [2,8,9,10]. Subsequently, 6-MP is converted by different enzyme systems: xanthine oxidase (XO), thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT), and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT). The XO catalyzes the conversion of 6-MP into a pharmacologically inactive metabolite called 6-thioric acid (6-TUA), while the enzyme TPMT forms 6-methylmercaptopurine (6-MMP) from 6-MP, and the enzyme HGPRT is responsible for transforming 6-MP into 6-thioinosine 5′-monophosphate (6-TIMP). 6-TIMP is catabolized by the enzymatic action of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPD) into 6-thioxanthosine 5′-monophosphate (6-TXMP), which in turn can be transformed into 6-thioguanosine 5′-monophosphate (6-TGMP) via the enzyme guanosine monophosphate (GMPS). 6-TGMP can be converted to 6-thioguanosine 5′-diphosphate (6-TGDP) and 6-thioguanosine 5′-triphosphate (6-TGTP) by two respective kinases. Within the nucleotide pool of 6-thioguanine (6-TGN), 6-TGTP (approximately 80% of TGN) and 6-TGDP (approximately 16% of TGN) are the main metabolites, while 6-TGMP is present only in traces. Therefore, 6-TGN levels are strongly correlated with 6-TGTP and 6-TGDP concentrations. 6-TGN has an average half-life of 5 days (range between 3–13 days), and all of them can be methylated by TPMT [3,16,17,18]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that an unusual AZA hydrolysis occurs in the presence of ruthenium, thus generating hypoxanthine instead of the expected 6-MP antimetabolite [19]. Hypoxanthine (6-hydroxypurine) is a deaminated form of adenine, and a constituent of the nucleoside inosine is formed during purine metabolism. It is found in both tissues and body fluids of human beings and animals, and it has been proposed as a biomarker for a variety of disease such as hypoxia, colorectal cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and cardiac ischemia [19].

Additionally, 6-TIMP is methylated by TPMT to subsequently form 6-methylthioinosine 5′-monophosphate (6-MTIMP), 6-methylthioinosine 5′-diphosphate (6-MTIDP), and 6-methylthioinosine 5′-triphosphate (6-MTITP). These last three metabolites are called 6-methylmercaptopurine ribonucleotides (6-MMPR). 6-TIMP can also be phosphorylated by the enzyme monophosphate kinase to form 6-thioinosine 5′-diphosphate (6-TIDP). Then, the enzyme diphosphate kinase forms 6-thioinosine 5′-triphosphate (6-TITP) and finally returns to 6-TIMP after an enzymatic reaction catalyzed by the enzyme inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPase) [17,20,21].

Regarding the metabolism of 6-TG, which is less complex than that of 6-MP and AZA, the absorption by the oral administration of 6-TG is incomplete and highly variable, generating a bioavailability of 14 to 46%, unlike absorption in the form of a prodrug (AZA) that can increase approximately 80% [17,20,21], as has been reported previously [15]. Both 6-MP and 6-TG are taken up by the HGPRT enzyme, which participates in the synthesis of nucleotide salvage from immune effector cells and is converted into their respective nucleoside monophosphate (TIMP and TGMP). In addition to the competitive catabolic reactions, TPMT by means of S-methylation inactivates 6-MP and 6-TG, and it XO converts 6-MP into 6-thiouric acid, which is an inactive compound.

Methylated TIMP (meTIMP), but not meTGMP, is an effective inhibitor of de novo purine biosynthesis. TIMP, which escapes catabolism, is further metabolized by inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) and guanine monophosphate (GMPS) to TGMP. The sequential action of deoxynucleoside kinases and reductase generates thio-GTP and thio-dGTP, which are the substrates for the incorporation of 6-TG into RNA and DNA [17,20]. The active metabolite of 6-TG inserts as an analogous base in DNA and RNA nucleic acids, inhibiting DNA repair, replication, and transcription [16,21].

Thiopurines enter the cells, by the membrane transporters for the respective nucleosides, which are then phosphorylated to the forms of nucleotides by the respective kinases mentioned above. Once the different forms of nucleotides are obtained, the step initial phosphorylation (flow regulator of the process) is through a nucleoside kinase, which leads to the production of a nucleotide monophosphate metabolite. Subsequently, a second phosphorylation step is carried out by the nucleotide monophosphate kinase, which generates a diphosphate nucleotide, and the third phosphorylation step is carried out by the nucleoside diphosphate kinase, which generates a nucleotide triphosphate. These forms can be incorporated into nucleic acids in competition with their homologous components, or they can inhibit nucleic acid synthesis by inhibiting essential enzymes such as polymerases [22,23].

When administering drugs, such as AZA, for a long time, it is important to bear in mind that they can generate toxicity, which is associated with two possible mechanisms: the first is the alteration in the cellular repair systems associated with DNA, specifically the alteration mediated by PCNa (proliferating cell nuclear antigen), for DNA polymerase-δ and the repair factor MutLα, MutL- exonuclease. The presence of a miscoded base analog (in this case, methyl 6-thioguanine (me6-TG) and methyl O6-guanine (O6-meG)) in the template chain can alter the repair system. Here, me6- Synthesized TG or O6-meG produced by a methylating agent directs the incorporation of thymine (T), forming Me6-TG:T or O6-meG:T. This condition activates MutSα-MutLα (cell repair factor), which triggers correction attempts that remain incomplete due to the impossibility of incorporating a base that can adequately complement the erroneous base. Consequently, structural alterations of DNA generated by incomplete repair attempts can be observed as breaks in DNA strands during the S phase of the next cell cycle, which become potentially lethal aberrant DNA structures that are substrates for recombination. This triggers the activation of the ATR proteins (ataxia telangiectasia and relation with Rad3) and ATRIP (protein that interacts with ATR), which are responsive to DNA damage with consequent signaling for phosphorylation of CHEK1 (serine/threonine kinase), which regulates phosphorylation of Cdc25 (threonine and tyrosine phosphatase) and thus the arrest of the G2 cell cycle [23]. The second mechanism is related to the ability to absorb ultraviolet radiation (UV), since thiopurines are nucleotides that have a superior capacity in the capture of ultraviolet radiation, which generates a considerable increase in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [17,23].

The various radical and nonradical types of ROS have the potential to induce direct harm to the components of DNA by creating oxidized bases and deoxyribose. Additionally, these ROS variants can cleave the phosphodiester backbone, leading to the formation of breaks in the DNA strand, either as single-stranded or double-stranded breaks. In addition, they can initiate reactions that generate secondary reactive species, such as aldehydes, which can also form DNA lesions. 6-Thioguanine is a very important target for oxidation, generating one of the main products in this process (GSO3, guanine 6-sulfonate). Proteins are also vulnerable to ROS, particularly those 1O2 that react with aromatic, basic and sulfur amino acids, altering the three-dimensional patterns of peptides and proteins, generating alterations in their function and secondary cellular damage [16,17,23].

ROS originate from two distinct types of reactions. In Type I reactions, thiopurine absorbs UVA energy, transitioning to an unstable excited triplet state. This state can then react with oxygen, resulting in the formation of a radical of thiopurine and superoxide (·O2). Subsequently, in a Fenton-type reaction, (·O2) is transformed into hydroxyl radicals (·OH), which pose a threat to cellular macromolecules. In Type II reactions, energy is directly transferred from absorbed radiation to ground-state triplet molecular oxygen (3O2), generating singlet oxygen (1O2), a nonradical with a longer half-life compared to most ROS. Both ·OH and 1O2 have the potential to cause mutagenic damage to DNA, encompassing strand breakage and oxidation-induced alterations in the constituent nitrogenous bases and deoxyribose [22,23].

In Figure 3, this metabolic process is presented, where the active compounds mentioned above have been related to the immunosuppressive effect and possible hepatotoxic effects in the patient treated with AZA.

Figure 3.

Azathioprine metabolism in orally administration. See text for details.

The immunosuppressive mechanism of action of thiopurines has not been fully clarified in 40 years of use, but the recognition of its metabolites has allowed us to determine its possible mechanism. MeTIMP is an inhibitor of the de novo synthesis of purines because it inhibits the synthesis of ADT and GTP, exerts an immunosuppressive effect, and blocks the proliferation of lymphoid cells. By the action of HGPRT, 6-TGN is converted into 6-thioguanosine 5-monophosphate (TGMP), which by the action of kinases and reductases forms deoxy-6-thioguanosine 5-triphosphate (dGS), that is incorporated into DNA and is able to stop the cell cycle and promote apoptosis [15].

Apoptosis is the final mechanism by which thiopurines exert their immunosuppressive effect [24]. There are two main signaling pathways (extrinsic and intrinsic) that control the initiation of apoptosis in mammals, which involve the participation of specialized proteolytic enzymes and caspases. Members of these protein families can be divided into antiapoptotic (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) and proapoptotic (Bax and Bak) proteins. Extrinsic pathways involve the participation of cell surface receptors belonging to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily and the consequent activation of caspase 8. The intrinsic cellular pathway involves the alteration of the mitochondrial membrane by pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family and the consequent release of factors, such as cytochrome c, that promote the activation of caspase-9. The activation of these caspases leads to the cleavage of a set of proteins, resulting in a characteristic pattern of gene expression and cell disassembly. Selective membrane permeability (MMP) is an important mechanism underlying cell death, where mitochondrial disruption culminates in a rapid loss of this mitochondrial membrane potential, a release of cytochrome c, and cell death [15].

In functional studies, it has been shown that AZA uses a caspase 9-dependent mitochondrial pathway that involves the negative relationship of Bcl-xL and the suppression of the mitochondrial membrane potential; the blockade of caspase 9 inhibits the apoptosis induced by AZA. These studies have shown that AZA and its derivatives 6-MP and 6-TG induce apoptosis in CD4 T lymphocytes in humans only in cells with activation of the Rac1 gene that is co-stimulated through CD28, which makes their use highly effective in the treatment of autoimmune diseases [24]. By inhibiting purine synthesis, AZA and 6-MP disrupts the proliferation of lymphocytes, which are key immune cells involved in the inflammatory process. This immunosuppressive effect helps modulating the aberrant immune response seen in autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases, and it is currently still being used in the treatment of systemic autoimmune disease, including overlap syndromes [3,25]. Also, by the same mechanism, interfering with the activation of T lymphocytes and blocking DNA synthesis in rapidly dividing immune cells AZA and its derivates in combination with other immunosuppressive drugs prevent allograft rejection after organ transplantation, by creating an immunosuppressive environment that allows the transplanted organ to integrate and function without being attacked by the recipient’s immune system [26,27].

In terms of the hepatotoxic and myelosuppressive side effects, it has been described as an idiosyncrasy linked to genetic variations of TPMT in humans, since TPMT activity is controlled by a common genetic polymorphism and one in 300 subjects has a very low enzymatic activity; this condition was first reported in 1989 in a study with adults who were administered AZA [28]. Very high serum levels of this enzyme cause the shunting of 6-MP to 6MMP, preferring its conversion to 6-TGN. Therefore, the serum concentration of 6-TGN nucleotides is reduced, thereby decreasing the myelosuppressive effect of AZA, and by increasing the serum concentration of 6MMP, the risk of hepatotoxicity increases [18]. The effects of AZA-induced myelosuppression related to TPMT deficiency have been documented in different groups of patients [29]. Although patients with deficiencies in TPMT synthesis should be treated with lower doses of thiopurines to avoid toxic concentrations of 6-TGN, these patients do not form 6-MeTIMP and can tolerate considerably higher concentrations of 6-TGN than patients with high levels of TPMT activity [15]. Likewise, it has established that polymorphisms of glutathione-S-transferase-M1 may influence AZA effects in young patients with inflammatory bowel disease by increasing the drug activation and by modulating oxidative stress and apoptosis [30].

However, TPMT deficiency does not absolutely contraindicate treatment with AZA or mercaptopurine. And, in humans, there are studies where TPMT measurements have been made to determine the doses of AZA to use and thus avoid a marked myelosuppression and/or hepatotoxic effect due to genetic variability in the amount of TPMT between individuals [18]. Similarly, in treatments that require the chronic use of AZA, it is necessary to perform a follow-up by measuring liver enzymes and serial hemograms to evaluate and avoid medical complications in the patient due to its side effects. And, although it has been reported that during AZA treatment there is an increase in serum aminotransferase (liver enzyme) levels, generally associated with high levels of 6-MP, the risk of severe liver dysfunction is low, and aminotransferase levels generally normalize a few weeks after discontinuation of treatment [31]. In canine studies, an increase in liver enzymes greater than twice the maximum values determined as normal parameters has been estimated in 15% of patients treated with AZA in the first two weeks, and thrombocytopenia or neutropenia in 8% of patients, which were evidenced approximately 6 weeks after starting treatment at an average dose of 1.9 mg/kg [32].

In veterinary medicine, regarding genetic variation associated with the amount of TPMT in dogs, it has been found that there are no associated differences between sex, age, and sterilization, but it was identified that giant Schnauzers have lower TPMT activity than other breeds and that Alaskan Malamutes have much higher activity, which could be an important factor to consider when evaluating the tolerability and efficacy of thiopurine treatment [33]. There are also reports where German Shepherds have shown a high risk of hepatotoxicity in the treatment with AZA [32].

Another important aspect that should be considered when performing therapy with AZA is the possible presentation of opportunistic infections, such as the presentation of disseminated cutaneous herpes zoster in humans, which has been described as a consequence of the infectious reactivation of the varicella zoster virus (VZV) that is latent in dorsal nodes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with pharmacological immunosuppression [34] or immunocompromised by other infectious agents, such as HIV-1 [35]. However, in a 2010 study that sought to determine herpes zoster infection from 1145 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), zoster was diagnosed in 51 patients with SLE (4.45%), where only 39.2% were administered AZA, the main trigger of viral infection being the concomitant treatment of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, and not the active disease [36]. Recently, it has been reported that AZA therapy selectively induced pronounced NK cell depletion and concomitant IFN-γ deficiency plus a specific contraction of classical TH1 cells leading to an increased occurrence of reactivation of endogenous latent herpesviruses [37].

AZA is commonly used in dogs for the treatment of some immune-mediated diseases, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, rheumatoid arthritis, immune-mediated polyarthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Evans syndrome, dermatological diseases, and other immune-mediated diseases [32,33]. In cats, AZA it is not used often due to the frequent appearance of bone marrow suppression evidenced in patients treated at an average dose of 2 mg/kg for intermediate days. This treatment often results in a hypocellular marrow with a significant reduction in the myeloid series, and even leads to respiratory tract infections [38].

4. Concluding Remarks and Future Prospects

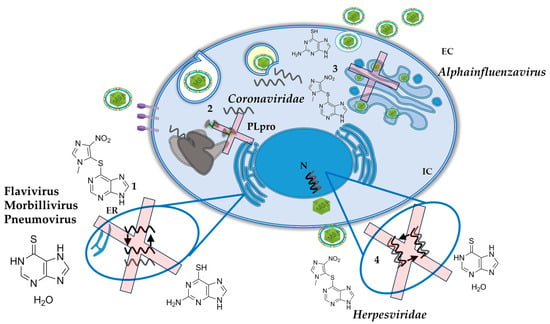

Given the scientific evidence of the metabolism of AZA and its derivatives, plus the studies that report a potential inhibitor of viral replication, mainly in viruses with RNA genome, AZA and its derivates could be included in the long list of potential medications for drug repurposing. Based on the revised literature, we could speculate that AZA and its derivates exert their antiviral effects, in most of the viruses, via a decrease purine synthesis pathway leading to a depletion of the intracellular nucleotide pool and decreasing the availability of nucleotides for the synthesis of RNA and DNA viruses (Figure 4). This also includes other pathways such as the inhibition of PLpro for Coronaviruses, and the activation of the unfolded protein response sensors for Influenza A virus. These non-common pathways need to be further evaluated.

Figure 4.

Schematic view of the potential antiviral targets of AZA and its derivates on different viruses. (1). Inhibition of replication in RNA Viruses. (2). Inhibition of PLpro for Coronaviruses. (3). Activation of the unfolded protein response sensors for Influenza A virus. (4). Inhibition of replication in human herpesviruses. See text for details.

Nucleotide metabolism is one of the more exploited host processes for the development of antiviral targets for several human viruses via design or repurposing [57]. Several cellular enzymes of the pathways for nucleotide biosynthesis have been successfully tested with promising inhibitors for different viruses [58]. Nucleosides and nucleotides as Direct Acting Antivirals (ATC: J05A) includes various compounds that can inhibit enzymes involved in purine synthesis. These drugs disrupt the ability of the viruses to replicate its genetic material such as mycophenolate, mofetil, and ribavirin, among others.

However, AZA does not belong to this group; AZA’s main therapeutic objective is immunosuppressive (ATC: L04AX01—antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents) and its approval goes in this therapeutic use. The evidence as antiviral in vitro is extensive, and the doses used for antiviral effect are lower immunosuppressive doses, which could favor the antiviral effect without the side effects of immunosuppression or hepatotoxicity. For AZA to become an antiviral approved drug, it is necessary to clarify the mechanism of antiviral action and strengthen the evidence that promote in vivo studies and clinical trials, especially in viruses that do not have an established therapeutic protocol and an effective vaccine to prevent it [57,59]. Moreover, existing drugs approved by regulatory agencies such as EMA and FDA could be chosen for novel antiviral treatments, often eliminating the necessity for pharmacokinetic and toxicological investigations [60]. For drug repurposing, the clinical trials of the approved drugs for their new application require a fundamental understanding of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [61]. However, the large amount of Phase IV and post-marketing data offer an extensive understanding in terms of drug candidate selection for the new application [62].

The thiopurine AZA/6-MP are used widely and have a moderately narrow therapeutic index, and it is important to recognize the risk factors that may lead to toxicity, especially myelosuppression. One risk factor is the genetic polymorphism of the enzyme TPMT, which is involved in the metabolism of the thiopurine drugs; patients with intermediate or deficient TPMT activity are at risk for excessive toxicity after receiving standard doses of thiopurine medications. Recent insights into pharmacogenomics of thiopurine drugs have led to labeling revisions. Adverse drug reactions such as influenza-like symptoms, rash, and pancreatitis are not explained by TPMT deficiency. Polymorphisms in the ITPase gene may account for these non–TPMT-related adverse effects [63]. There, a strong role from AZA as a procarcinogenic drug has also been reported, both in organ transplant recipients and in other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, particularly IBD [64]. Likewise, a mutational signature analysis on cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) primary tumors has revealed the presence of a novel signature, whose incidence correlates with chronic exposure to AZA increasing the risk for cutaneous malignancy in AZA-treated patients [65]. Although adverse effects are mainly reported in chronic use, the understanding of acute adverse effects is critical for the wide implementation and use of thiopurines as antivirals, in addition to the dose and pharmacokinetic understanding of the antiviral pathway for different viruses.

In addition, molecular docking studies combined with medicinal chemistry can be carried out that seek to improve the activity and pharmacokinetic properties of AZA and its derivatives. Therefore, it is crucial to advocate for the utilization of secure and efficient broad-spectrum repurposed drugs, such as AZA and its derivates, as antivirals. This approach aims to prevent the damages of viral diseases in both human and veterinary medicine, thereby broadening the spectrum of available medications to impede the spread and occurrence of emerging and re-emerging viral diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.-S. and M.M.-G.; methodology, J.R.-S.; software, J.R.-S.; validation, J.R.-S. and M.M.-G.; formal analysis, C.R.-U.; investigation, C.R.-U.; resources, C.R.-U.; data curation, C.R.-U.; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.-U.; writing—review and editing, C.R.-U., J.R.-S. and M.M.-G.; visualization, C.R.-U.; supervision, J.R.-S.; project administration, J.R.-S.; funding acquisition, J.R.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONADI-UCC, grant number INV3236 to J.R.-S and The APC was funded by CONADI-UCC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hitchings, G.H.; Elion, G.B. The chemistry and biochemistry of purine analogs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1954, 60, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elion, G.B.; Hitchings, G.H. Azathioprine. In Antineoplastic and Immunosuppressive Agents: Part II; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1975; pp. 404–425. [Google Scholar]

- Broen, J.C.A.; van Laar, J.M. Mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine and tacrolimus: Mechanisms in rheumatology. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, D.A.; Philips, F.; Sternberg, S.; Stock, C.; Elion, G. 6-Mercaptopurine: An inhibitor of mouse sarcoma 180. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1953, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D.A.; Philips, F.S.; Sternberg, S.S.; Stock, C.C.; Elion, G.B.; Hitchings, G.H. 6-Mercaptopurine: Effects in mouse sarcoma 180 and in normal animals. Cancer Res. 1953, 13, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, K. The effect of 6-thiopurine and of 1, 9-di (methane sulfonoxy) nonane on the growth of a variety of mouse and rat tumors. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1953, 1, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Philips, F.; Sternberg, S.; Clarke, D.; Hitchings, G. Effects of 6-mercaptopurine in mammals. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1953, 1, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Burchenal, J.H.; Murphy, M.L.; Ellison, R.R.; Sykes, M.P.; Tan, T.C.; Leone, L.A.; Karnofsky, D.A.; Craver, L.F.; Dargeon, H.W.; Rhoads, C.P. Clinical evaluation of a new antimetabolite, 6-mercaptopurine, in the treatment of leukemia and allied diseases. Blood 1953, 8, 965–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, R.; Stack, J.; Dameshek, W. Effect of 6-mercaptopurine on antibody production. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1958, 99, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calne, R.Y. The rejection of renal homografts. Inhibition in dogs by 6-mercaptopurine. Lancet 1960, 1, 417–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.E.; Merrill, J.P.; Harrison, J.H.; Wilson, R.E.; Dammin, G.J. Prolonged survival of human-kidney homografts by immunosuppressive drug therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1963, 268, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, M.S.; Kaplan, J.C. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987, 31, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariri, R.; Khalili, G. Synthesis of purine antiviral agents, hypoxanthine and 6-mercaptopurine. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 38, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, M.C. Azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine in inflammatory bowel disease: Pharmacology, efficacy, and safety. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 2, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cara, C.J.; Pena, A.S.; Sans, M.; Rodrigo, L.; Guerrero-Esteo, M.; Hinojosa, J.; Garcia-Paredes, J.; Guijarro, L.G. Reviewing the mechanism of action of thiopurine drugs: Towards a new paradigm in clinical practice. Med. Sci. Monit. 2004, 10, RA247–RA254. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, R.; Ferrara, F.; Muller, C.; Dreyer, A.Y.; McLeod, D.D.; Fricke, S.; Boltze, J. Immunosuppression for in vivo research: State-of-the-art protocols and experimental approaches. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2017, 14, 146–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karran, P.; Attard, N. Thiopurines in current medical practice: Molecular mechanisms and contributions to therapy-related cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, M.; Khan, U. Azathioprine and the neurologist. Pract. Neurol. 2020, 20, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orts-Arroyo, M.; Castro, I.; Martínez-Lillo, J. Detection of Hypoxanthine from Inosine and Unusual Hydrolysis of Immunosuppressive Drug Azathioprine through the Formation of a Diruthenium(III) System. Biosensors 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, N.K.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Jharap, B.; de Graaf, P.; Mulder, C.J. Drug Insight: Pharmacology and toxicity of thiopurine therapy in patients with IBD. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 4, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gelder, T.; van Schaik, R.H.; Hesselink, D.A. Pharmacogenetics and immunosuppressive drugs in solid organ transplantation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2014, 10, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantini, M.C.; Becker, C.; Kiesslich, R.; Neurath, M.F. Drug insight: Novel small molecules and drugs for immunosuppression. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 3, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordheim, L.P.; Durantel, D.; Zoulim, F.; Dumontet, C. Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiede, I.; Fritz, G.; Strand, S.; Poppe, D.; Dvorsky, R.; Strand, D.; Lehr, H.A.; Wirtz, S.; Becker, C.; Atreya, R. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target of azathioprine in primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, L.; Phulukdaree, A.; Soma, P. Effective long-term solution to therapeutic remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Role of Azathioprine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 100, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocair, P.R.; Neves, P.; Mohrbacher, S.; Neto, M.P.; Sato, V.A.H.; Oliveira, E.S.; Barbosa, L.V.; Bales, A.M.; da Silva, F.P.; Cuvello-Neto, A.L.; et al. Case Report: Azathioprine: An Old and Wronged Immunosuppressant. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 903012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevins, T.E.; Thomas, W. Quantitative patterns of azathioprine adherence after renal transplantation. Transplantation 2009, 87, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennard, L.; Van Loon, J.A.; Weinshilboum, R.M. Pharmacogenetics of acute azathioprine toxicity: Relationship to thiopurine methyltransferase genetic polymorphism. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1989, 46, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennard, L. TPMT in the treatment of Crohn’s disease with azathioprine. Gut 2002, 51, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, G.; Pelin, M.; Franca, R.; De Iudicibus, S.; Cuzzoni, E.; Favretto, D.; Martelossi, S.; Ventura, A.; Decorti, G. Pharmacogenetics of azathioprine in inflammatory bowel disease: A role for glutathione-S-transferase? World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3534–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiegelow, K.; Nielsen, S.N.; Frandsen, T.L.; Nersting, J. Mercaptopurine/Methotrexate maintenance therapy of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Clinical facts and fiction. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 36, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallisch, K.; Trepanier, L.A. Incidence, timing, and risk factors of azathioprine hepatotoxicosis in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2015, 29, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, L.B.; Salavaggione, O.E.; Szumlanski, C.L.; Miller, J.L.; Weinshilboum, R.M.; Trepanier, L. Thiopurine methyltransferase activity in red blood cells of dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2004, 18, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvariño, R.; Tafuri, J.; Mérola, V.; Romero, C.; Alonso, J. Herpes zóster cutáneo diseminado en paciente con artritis reumatoide. Arch. Med. Interna 2010, 32, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo, A.; Uranga, A.I.; D’Atri, G.; Deane, L.; Olivares, L.; Pizzariello, G.; Forero, O.; Coringrato, M.; Maronna, E. Herpes simplex en pacientes inmunocomprometidos por HIV y terapia esteroidea en dermatosis ampollares. Dermatol. Argent. 2011, 17, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Borba, E.F.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Martin, P.; Costa, L.P.; Guedes, L.K.; Bonfa, E. Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of Herpes zoster in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010, 16, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingelfinger, F.; Sparano, C.; Bamert, D.; Reyes-Leiva, D.; Sethi, A.; Rindlisbacher, L.; Zwicky, P.; Kreutmair, S.; Widmer, C.C.; Mundt, S.; et al. Azathioprine therapy induces selective NK cell depletion and IFN-gamma deficiency predisposing to herpesvirus reactivation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 280–286.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, K.M.; Altman, D.; Clemmons, R.R.; Bolon, B. Systemic toxicosis associated with azathioprine administration in domestic cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1992, 53, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R.C.; Carson, D.A.; Seegmiller, J.E. Adenosine kinase initiates the major route of ribavirin activation in a cultured human cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 3042–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, S.; Taipalensuu, J.; Peterson, C.; Almer, S. IMPDH activity in thiopurine-treated patients with inflammatory bowel disease–relation to TPMT activity and metabolite concentrations. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 65, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraki, K.; Ishibashi, M.; Okuno, T.; Kokado, Y.; Takahara, S.; Yamanishi, K. Effects of cyclosporine, azathioprine, mozoribine, and prednisolone on replication of human cytomegalovirus. Transplant. Proc. 1990, 22, 1682–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki, K.; Ishibashi, M.; Okuno, T.; Namazue, J.; Yamanishi, K.; Sonoda, T.; Takahashi, M. Immunosuppressive dose of azathioprine inhibits replication of human cytomegalovirus in vitro. Arch. Virol. 1991, 117, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, J.R.; Carroll, K.L.; Illichmann, M.; Striker, R. Effect of antimetabolite immunosuppressants on Flaviviridae, including hepatitis C virus. Transplantation 2004, 77, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, S.; Striker, R. Thiopurines inhibit bovine viral diarrhea virus production in a thiopurine methyltransferase-dependent manner. J. Gen. Virol. 2008, 89, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.Y.; Chien, C.H.; Han, Y.S.; Prebanda, M.T.; Hsieh, H.P.; Turk, B.; Chang, G.G.; Chen, X. Thiopurine analogues inhibit papain-like protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 75, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.Y.; Keating, J.A.; Hoover, S.; Striker, R.; Bernard, K.A. A thiopurine drug inhibits West Nile virus production in cell culture, but not in mice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.W.; Cheng, S.C.; Chen, W.Y.; Lin, M.H.; Chuang, S.J.; Cheng, I.H.; Sun, C.Y.; Chou, C.Y. Thiopurine analogs and mycophenolic acid synergistically inhibit the papain-like protease of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Antivir. Res. 2015, 115, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, O.V.; Felix, D.M.; de Mendonca, L.R.; de Araujo, C.; de Oliveira Franca, R.F.; Cordeiro, M.T.; Silva Junior, A.; Pena, L.J. The thiopurine nucleoside analogue 6-methylmercaptopurine riboside (6MMPr) effectively blocks Zika virus replication. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 50, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, O.V.; Felix, D.M.; de Camargo Tozato, C.; Fietto, J.L.R.; de Almeida, M.R.; Bressan, G.C.; Pena, L.J.; Silva-Junior, A. 6-methylmercaptopurine riboside, a thiopurine nucleoside with antiviral activity against canine distemper virus in vitro. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.H.; Xu, Z.X.; Jiang, N.; Zheng, Y.P.; Rameix-Welti, M.A.; Jiao, Y.Y.; Peng, X.L.; Wang, Y.; Eleouet, J.F.; Cen, S.; et al. High-throughput screening of active compounds against human respiratory syncytial virus. Virology 2019, 535, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaine, P.D.; Kleer, M.; Duguay, B.A.; Pringle, E.S.; Kadijk, E.; Ying, S.; Balgi, A.; Roberge, M.; McCormick, C.; Khaperskyy, D.A. Thiopurines activate an antiviral unfolded protein response that blocks influenza A virus glycoprotein accumulation. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e00453-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, T.; Saito, S.; Auerbach, J.; Williams, T.; Moreen, T.R.; Jazwinski, A.; Cruz, B.; Jeurkar, N.; Sapp, R.; Luo, G.; et al. An in vitro model of hepatitis C virion production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 2579–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekry, A.; Gleeson, M.; Guney, S.; McCaughan, G.W. A prospective cross-over study comparing the effect of mycophenolate versus azathioprine on allograft function and viral load in liver transplant recipients with recurrent chronic HCV infection. Liver Transpl. 2004, 10, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hernández, M.Y.; Ruiz-Saenz, J.; Martínez-Gutiérrez, M. Coinfection of Zika with Dengue and Chikungunya virus. In Zika Virus Biology, Transmission, and Pathology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chou, C.Y.; Chang, G.G. Thiopurine analogue inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus papain-like protease, a deubiquitinating and deISGylating enzyme. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2009, 19, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, C.; Khaperskyy, D.A. Translation inhibition and stress granules in the antiviral immune response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercorelli, B.; Palu, G.; Loregian, A. Drug Repurposing for Viral Infectious Diseases: How Far Are We? Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, C.S.; García, C.C.; Damonte, E.B. Inhibitors of Nucleotide Biosynthesis as Candidates for a Wide Spectrum of Antiviral Chemotherapy. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Nascimento, I.J.; de Aquino, T.M.; da Silva-Junior, E.F. Drug Repurposing: A Strategy for Discovering Inhibitors against Emerging Viral Infections. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 2887–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.A.; Roth, B.L. Finding new tricks for old drugs: An efficient route for public-sector drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, J.; Mohan, M.; Byrareddy, S.N. Drug Repurposing Approaches to Combating Viral Infections. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, Y.; Erez, T.; Reynolds, I.J.; Kumar, D.; Ross, J.; Koytiger, G.; Kusko, R.; Zeskind, B.; Risso, S.; Kagan, E.; et al. Drug repurposing from the perspective of pharmaceutical companies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahasranaman, S.; Howard, D.; Roy, S. Clinical pharmacology and pharmacogenetics of thiopurines. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 64, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, I.M.; Proby, C.M.; Inman, G.J.; Harwood, C.A. Azathioprine: Friend or foe? Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 180, 961–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inman, G.J.; Wang, J.; Nagano, A.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Purdie, K.J.; Taylor, R.G.; Sherwood, V.; Thomson, J.; Hogan, S.; Spender, L.C.; et al. The genomic landscape of cutaneous SCC reveals drivers and a novel azathioprine associated mutational signature. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).