Abstract

For early and long-term patient and graft survival, drug therapy in solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation inevitably involves polypharmacy in patients with widely varying and even abruptly changing conditions. In this second part, relevant medication briefing is provided, in addition to the scores defined in the previously published first part on the design of the Individual Pharmacotherapy Management (IPM). The focus is on the growing spectrum of contemporary polypharmacy in transplant patients, including early and long-term follow-up medications. 1. Unlike the available drug–drug interaction (DDI) tables, for the first time, this methodological all-in-one device refers to the entire risks, including contraindications, special warnings, adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and DDIs. The selection of 65 common critical drugs results from 10 years of daily IPM with real-world evidence from more than 60,800 IPM inpatient and outpatient medication analyses. It includes immunosuppressants and typical critical antimicrobials, analgesics, antihypertensives, oral anticoagulants, antiarrhythmics, antilipids, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antipropulsives, antiemetics, propulsives, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), sedatives, antineoplastics, and protein kinase inhibitors. As a guide for the attending physician, the drug-related risks are presented in an alphabetical overview based on the Summaries of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) and the literature. 2. Further briefing refers to own proven clinical measures to manage unavoidable drug-related high-risk situations. Drug-induced injuries to the vulnerable graft and the immunosuppressed comorbid patient require such standardized, intensive IPM and the comprehensive preventive briefing toolset to optimize the outcomes in the polypharmacy setting.

1. Introduction

There are well-established drug–drug interaction (DDIs) risks for the calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), cyclosporine A (CsA) and tacrolimus (TAC), and almost analogously for the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORIs), everolimus (EVR) and sirolimus (SIR), to be considered, as listed throughout the transplantation decades in the literature. Their adverse drug reactions (ADRs) with risks of serious infections, renal, neurologic, and further toxicities and malignancies predominantly depend on their small therapeutic window and, therefore, inevitably require therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). The risk of ADRs becomes even enhanced with a broad spectrum of concomitant drugs and transient or persistent intestinal or hepatic dysfunction with impaired P-gp-efflux, CYP34A metabolism, and drug elimination capacity [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. In the first part of this series on Individual Pharmacotherapy Management (IPM) in posttransplant polypharmacy, the design of a self-established IPM procedure in conjunction with the TDM of the immunosuppressants has been published [9]. The necessity of the constant focus on the defined patient scores and medication scores as the basis of the IPM was outlined.

The relevance of the medication risk is already obvious in the pretransplant patient requiring liver transplantation for acute hepatic failure. Drug-induced hepatotoxic injuries cause 15% of cases of acute hepatic failure [10]. As from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) liver transplant database study, acute hepatic necrosis, resulting from acetaminophen (APAP) alone, or in combination with another drug, accounted for 49%; in the non-APAP group, the most frequently implicated drugs were isoniazid, propylthiouracil, phenytoin, and valproate, with 17.5 to 7.3% [10]. Severe drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the most common identifiable cause of acute liver failure in the United States (US) [10]. According to the results of a US prospective multicenter study, the pattern in most frequent apparent causes of acute liver failure has changed, and APAP overdose and idiosyncratic drug reactions have replaced viral hepatitis [11]. Focusing on liver safety following liver transplantation, a Spanish research group emphasizes in their review the urgent need for the awareness of hepatotoxic ADRs to prevent posttransplant DILI. They highlight the need for further research and collaboration, as this topic remains under-recognized, especially in terms of associated risk factors and higher vulnerability of the transplant [12]. The regularly updated LiverTox database site provides unbiased clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury [13] to be looked up for single agents.

A Dutch multicenter study identified 14 drug groups to be associated with a higher risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) after adjustment for confounding [14].

These are only the peaks. However, in parallel, we have to assume an extensively higher portion of patients suffering from less severe stages or non-identified drug injuries. According to a review on drug-induced nephrotoxicity, drugs cause approximately 20% of community- and hospital-acquired events of acute renal failure. In the elderly adults, the incidence of drug-induced nephrotoxicity reaches 66% [15]. This patient group may be partly comparable with similar vulnerable kidney transplant patients. One or more common pathogenic mechanisms have been observed in drug-induced nephrotoxicity, such as altered intraglomerular hemodynamics, tubular cell toxicity, acute or chronic interstitial nephritis, inflammation, crystal nephropathy, rhabdomyolysis, and thrombotic microangiopathy [15]. For preventive measures, knowledge of the drugs causative of these ADRs is essential.

The unavoidable polypharmacy post transplantation increases with the pre-existing concomitant comorbidities and metabolic disorders of the individual patient, the latter being even further iatrogenically promoted by the immunosuppressive regimens themselves, as we already addressed in the 1990s [16,17,18,19,20]. In 1996, we referred to the dilemma of the iatrogenic medication risks as “chronic allograft destruction versus chronic allograft rejection” [21]. This has been confirmed during the years hereafter in several studies, including a review by Halloran [22]. As polypharmacy affects all types of transplantation in both, the acute and the long-term posttransplantation periods, the precise individual patient condition must always be contextualized with the medication scores to prevent harm to the graft and patient from the earliest stage possible. For this purpose, focusing on the elimination of any drug-induced iatrogenic graft and patient injury, we conceptualized an individual pharmacotherapy management (IPM), being implemented in addition to the TDM of the immunosuppressants. The IPM concept has been introduced and published ahead of this as the first part of this drug safety series [9]. On a daily basis for more than a decade of IPM experience, from over 60,800 authors’ own medication reviews in polypharmacy, a broad spectrum of aspects has arisen to be considered in order to eliminate drug-induced iatrogenic injuries to the allograft and the patient. Yet, it is almost impossible to study all the Summaries of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) up to even >100 pages for a single drug in the clinical routine. But there are no overviews, except for DDIs or toxicity risks, available for the practice of challenging polypharmacy posttransplantation.

The aim of this second and complementary part of the series on drug safety in transplant polypharmacy is to provide instruments for the immense challenges posed by the IPM-defined medication scores. The spectrum of frequently coadministered medications in polypharmacy after transplantation is extremely broad, as the author has experienced over 10 years of IPM and 21 years of daily posttransplant TDM reviewing of immunosuppressants. Every transplant physician needs to be aware and educated not only on the DDIs, but also on the ADRs, contraindications, and warnings of concomitant medications in the polypharmacy context. There is no standard procedure to systematically review the individual risks of polypharmacy, despite the particular vulnerability of the transplant patient and graft. And there is no comprehensive resource covering the risks of the current common polypharmacy agents in total. This would mean an overdue and helpful tool for clinical and outpatient physicians is needed. Furthermore, from the author’s own experience, this is needed not only for the transplant team, but also for the various disciplines that are unfamiliar with the risks of posttransplant polypharmacy, despite treating transplant patients in the long-term follow-up for eventually upcoming surgeries and diseases. Therefore, this second paper is intended to provide additional practical devices for the awareness of these almost unmanageable challenges of defined medication scores. As an extract of the clinically relevant aspects of today’s commonly coadministered drugs, covering contraindications, ADRs, DDIs, and drug-specific warnings, it is intended to be a useful tool for obtaining initial information in daily practice, rather than an unmanageable, time-consuming study of multiple SmPC brochures of 10 to >100 pages each.

As a practical combined toolset, the latest SmPCs covering drug information from clinic and research and further literature data are extracted and tabulated alphabetically. Clinical IPM countermeasures and preventive approaches based on 10 years of IPM experience are presented to overcome unavoidable high-risk situations, such as those indicated by the antibiogram or the antimicrobial resistance chart, which requires the risky coadministration of targeted antimicrobials without effective alternatives.

2. Methods

2.1. IPM Concept and Implementation of a Digital Interdisciplinary Networking Strategy [9]

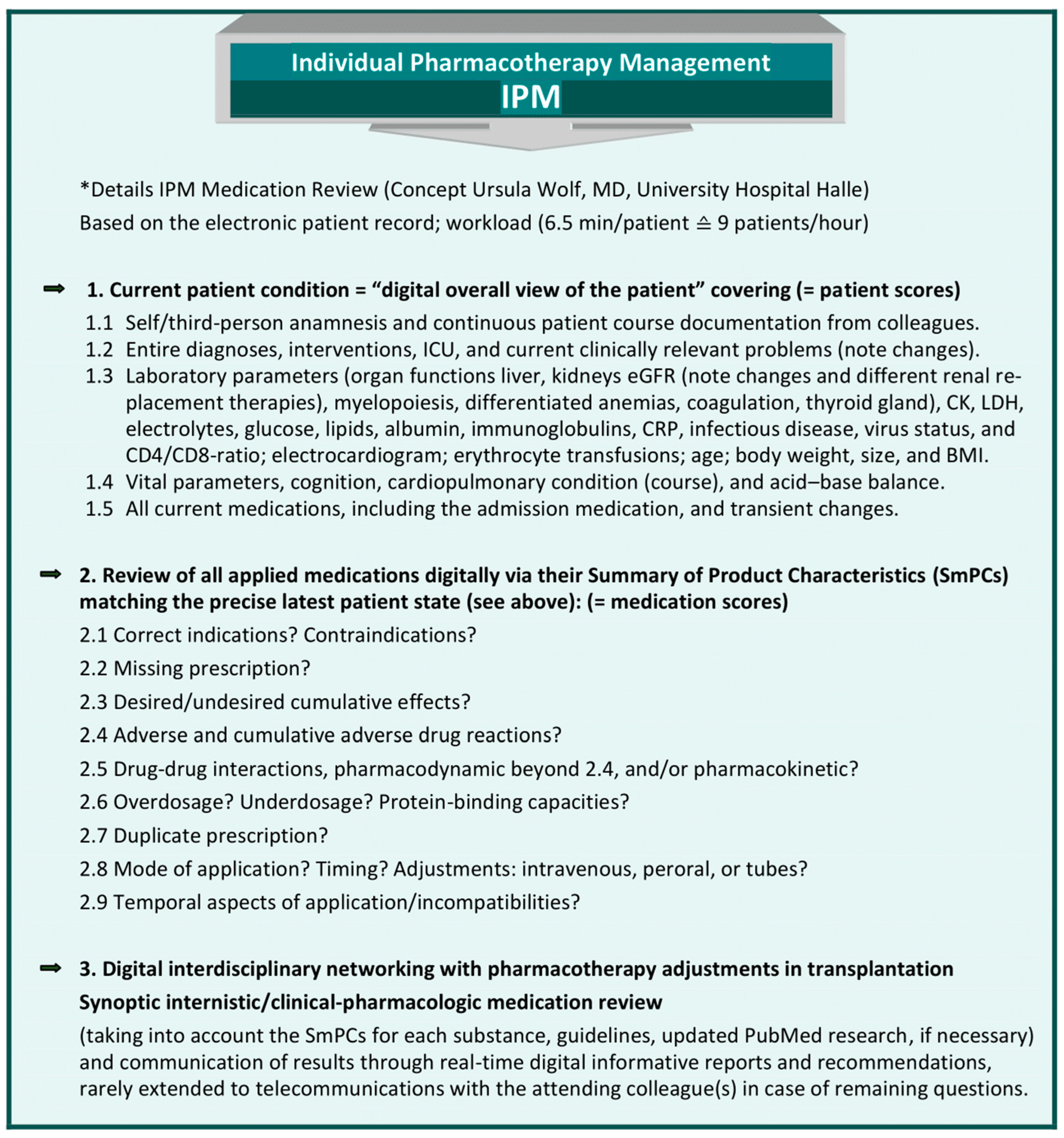

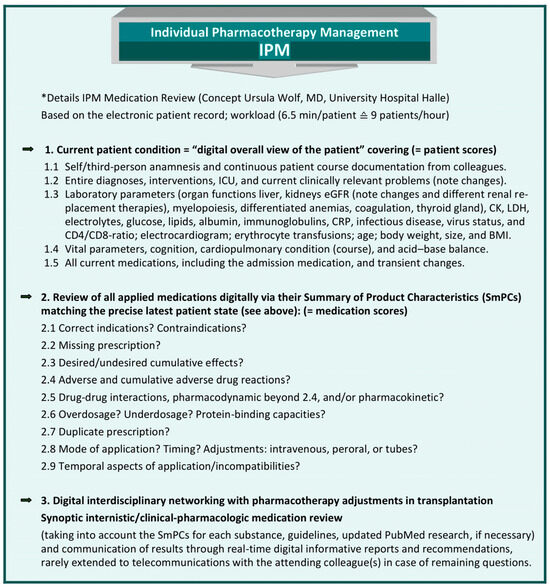

At the University Hospital Halle (UKH), the IPM procedure has been designed and implemented for 10 years [Figure 1]. The IPM scores were determined by the author with disciplinary education and 12 years of experience in internal medicine, plus 6 years in clinical pharmacology and 6 years in transplantation. She designed and has administered the IPM, with up to >60,800 of her own IPM reviews. The scores are primarily based on her daily experience with multimorbid patients in polypharmacy. Their disease condition and laboratory parameters, with the individual impact on drug and patient safety, led to the patient scores. In addition to DDIs, the medication information required for an adequate and comprehensive individual medication analysis must also comprise ADRs, contraindications, dosing, and drug-specific warnings. These are reflected by the medication scores defined for the IPM. The IPM is conducted as a synopsis of internal medicine and clinical pharmacology. To ensure reproducibility for other healthcare professionals, the systematic standardized format is precisely outlined. The IPM is combined with the individual trough-level TDM of immunosuppressants in patients undergoing solid organ or allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [9]. It provides continuous interdisciplinary networking, based on each patient’s electronic medical record from the start of transplantation. The reproducible IPM protocol refers to the most accurate current clinical condition of the patient with respect to his organ functions and vital parameters. In order to match the prescribed medications to the patient’s degradation and elimination capacities, taking into account the real-time concurrently manifest pharmacokinetic DDIs, the entire medication list is analyzed based on the SmPC for ADRs, including pharmacodynamic DDIs, contraindications, warnings, and dosages. Additional tools are used in complicated situations, such as continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) [23,24,25], and for further interaction checks in the case of open questions [26,27] and PubMed research.

Figure 1.

Comprehensive, reproducible IPM, based on the electronic patient record (adapted from [9], Pharmaceutics, 2023). * IPM (applied patient and medication scores), based on the electronic hospital patient record at Halle University Hospital, conceptualized, implemented, and practiced by Wolf, MD, Head of Pharmacotherapy Management Department, Specialist in Internal Medicine, with expertise in Clinical Pharmacology and Transplantation, performed > 60,800 individual medication reviews.

2.2. Briefing Toolset on Relevant IPM Medication Scores and Preventive Countermeasures to Avoid Iatrogenic Patients and Graft Injuries

First, a research on overviews of medication-related injuries in transplants and patients in PubMed was performed. There have been constantly ongoing case reports and lists of potentially nephrotoxic or hepatotoxic agents and of DDIs, especially with a focus on the CNIs and mTORIs throughout the decades of transplantation. However, from the review, there are no comprehensive methodological approaches to standardize a drug safety procedure in transplantation to eliminate the severe risks, which result from the individual polypharmacy setting.

1. To provide devices for the designed and approved IPM procedure with reference to the defined IPM medication scores for clinical and ambulatory practices, the contemporary drug combinations in early and long-term posttransplant polypharmacy are addressed. The focus is on the most common critical coadministered drugs experienced by the 10 years of IPM and scoping reviewed via their latest SmPCs and PubMed research for each active ingredient. A tabulized overview is to provide a broader spectrum of drug-related risks, unlike the available DDI lists. In this briefing, ADR plus DDI plus contraindication plus drug-specific warnings are included to enable the IPM performance according to the defined medication scores, and to adapt them to the patient scores. The author’s own real-world insights from daily IPM in organ transplantation and HSCT with more than 60,800 self-conducted IPMs force to address a wide spectrum of critical medication entities to preserve grafts and patients from iatrogenic drug-induced injury. In consequence, the tabulized relevant medications comprise the four classes of immunosuppressive maintenance drugs: CNIs TAC and CsA, antiproliferative agents mycophenolate mofetil, mycophenolate sodium, mTOR inhibitors SIR and EVR, and steroid prednisolone, typical critical antimicrobials, analgesics and antipyretics, antihypertensives, ß-blockers, antiarrhythmics, oral anticoagulants, antilipids, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antipropulsives, antiemetics, propulsives, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), sedatives, antineoplastics, and protein kinase inhibitors. Their tabulized extracted information is intended to provide the essence for the daily routine from each drug’s SmPC brochure, further DDI checks, and PubMed research data. The table format with the alphabetical listing of drugs and their classification into DDIs, ADRs, contraindications, and drug-specific warnings is to provide an easy and most practical way to find them in everyday clinical practice.

It is important to be aware that these aspects do not reflect the entire drug information, nor do they include specific issues, such as hypersensitivity, children, pregnancy, lactation, congenital metabolic malfunctions and intolerances, genetic variants [28,29,30], dysphagia [31], and specified dosing regimens, the latter requiring modification according to each patient’s individual, eventally abruptly changing, degrading/eliminating capacities and comedication. There is no further grading of each referenced risk since the individual patient’s condition and the different medication lists themselves always have a modulating impact.

2. For further briefing from the decade of IPM evidence, the practiced tailored countermeasures are presented. They are to provide preventive tools for frequent risk situations, such as drug-induced renal injury, QTc prolongation, rhabdomyolysis, hemorrhages, wound-healing problems, pain management, and others to avoid harm to patient and graft.

3. Results

3.1. IPM in Practice

IPM based on the defined patient and medication scores proved to be the most effective, with a 100% relative reduction in the prevention of, for example, nephrotoxicity and renal impairment as analogously applied in elderly patients [32]. A constant awareness of the real-time interference of drug degradation capacities and patient status, both of which are affected by multiple, often abruptly changing patient and multimedication conditions, is the sine qua non in polypharmacy.

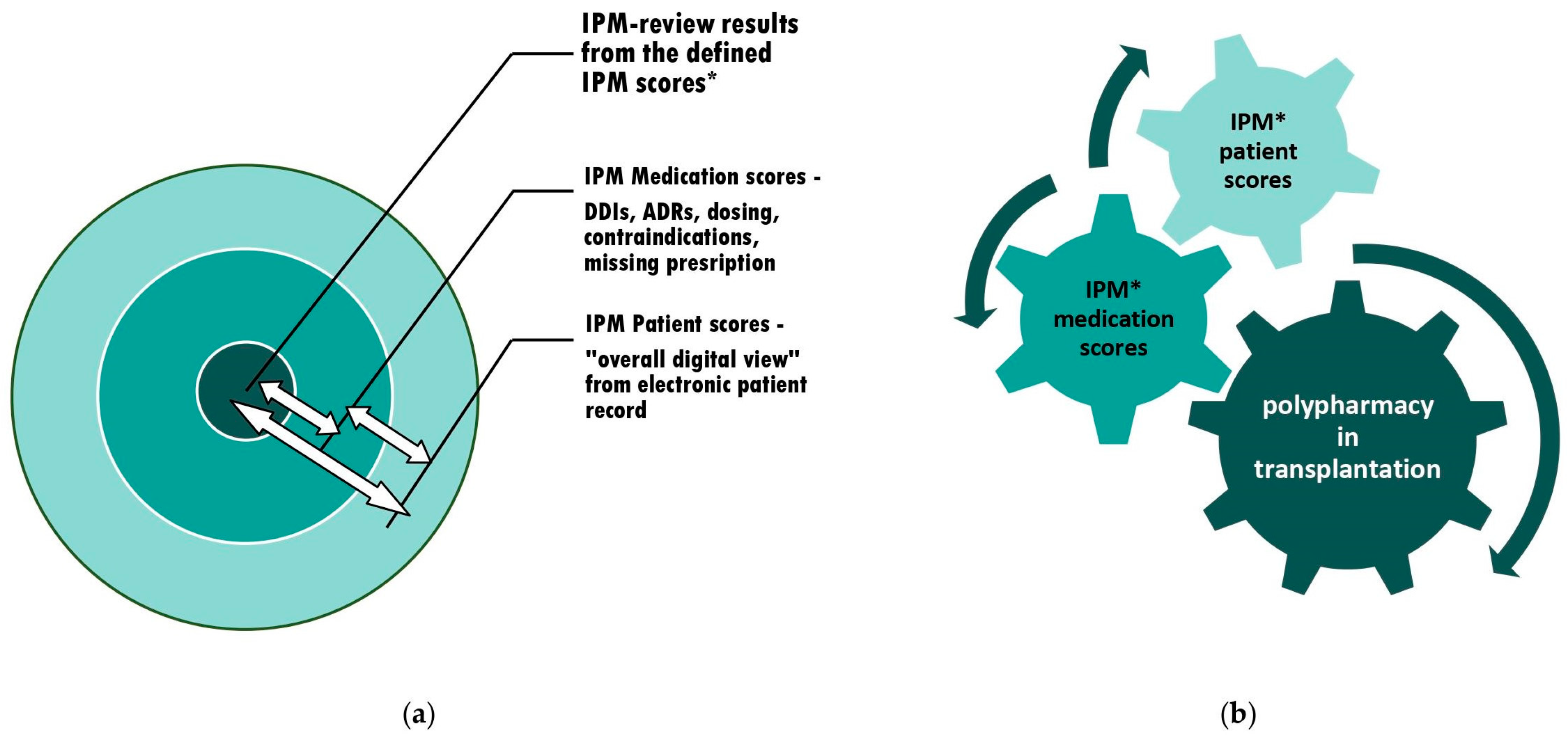

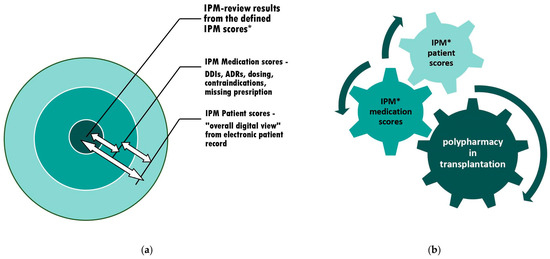

The transplant patient is even more vulnerable: the narrow therapeutic window of his/her CNI or mTORI is very susceptible to comedications that might either cumulatively increase the ADR risks of the immunosuppressant and other drugs, and/or, furthermore, often interact with the immunosuppressant’s and other drugs’ effects and ADRs in a pharmacodynamic and/or pharmacokinetic manner. Taking this into account in the individual patient for each drug remains an enormous professional challenge for the treating physician, either in the acute or long-term posttransplant setting [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The context of appropriate polypharmacy assessments and subsequent adjustments: (expanded version of [9], Pharmaceutics, 2023) (a) The individual circuits affect each other. Therefore, interference monitoring is required. (b) The optimization of polypharmacy by continuous synoptic contribution and the adaptation to confounding risks from varying current patient condition and altering comedications through simultaneous IPM in real-time. An additional IPM toolset with tabulated medication scores for 65 commonly coadministered medications and a practice-oriented briefing on counteracting risk situations is provided. * IPM scores see Figure 1.

With a daily routine and a comprehensive electronic patient record the IPM takes an average of only 6.5 min. It enables seamless, digital, real-time interdisciplinary networking, and is also applicable in addition to any TDM-based drug dosing [9]. The resulting recommendations for the attending colleagues are communicated digitally in real time, and in rare cases also telemedically for remaining open questions. The interprofessional applicability and reproducibility of the IPM procedure by instructed clinical pharmacists has been tested positive. There is no need for on-site expertise or capacity, as the digital basis enables real-time IPM via the electronic health record from any remote location.

3.2. Tabulated Extracts as the Relevant Medication Scores of Common Critical Coadministered Drugs in Posttransplant Polypharmacy

In particular, the IPM medication scores require the intensive and time-consuming study of SmPCs, DDI checks, dosing analyses, and possibly additional literature research. Without a daily routine that minimizes these efforts, this may be unmanageable for physicians or pharmacists who are not as familiar with each drug. For this reason, excerpts from the daily IPM drug reviews, based primarily on the updated drug SmPCs, are presented in tabular form in alphabetical order of the drug name for easy navigation [Table 1]. It aims to provide the most important clinically relevant information from the extensive SmPCs of those drugs that are frequently coadministered in the transplant patient. It provides guidance on clinically relevant ADRs, DDIs, and contraindications in a single overview. The drugs selected have been chosen to cover the most common critical prescriptions in posttransplant polypharmacy. The table specifically addresses medications commonly used in either the acute or long-term period after organ transplantation and HSCT, as seen from real-world IPM in these often high-risk settings.

Table 1.

IPM medication scores extracts from the SmPCs of 65 applied drugs (alphabetical order) in transplantation with selected risks (not graded) to be recognized from ADRs (from reported placebo-controlled studies and from post-marketing experience), pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic DDIs, contraindications (CI), and dosing aspects in contemporary polypharmacy in the context of solid organ transplantation and HSCT, with reference to CNIs and mTORIs, cortisone, and MMF.

As experienced and emerged from the lack of availability in repeatedly reviewed real-world IPM, the table includes the CNIs and mTORIs, MMF, prednisolone, critical antibiotics, antifungals, antivirals, analgesics, antipyretics, antihypertensives, antilipids, antidepressants, PPIs, antipsychotics, sedatives, propulsives, antipropulsives, antiemetics, antiarrhythmics, anticoagulants, antineoplastics, and protein kinase inhibitors.

The excerpts from the updated SmPCs include ADRs and DDIs from reported placebo-controlled trials and from post-marketing experience, which are not further graded here. The essence results from the focus on graft and patient toxicity risks from ADRs, DDIs, contraindications, and additional drug-specific issues to be considered [Table 1].

3.3. Briefing on Awareness and Preventive Countermeasures in Unavoidable Drug-Induced Risk Situations

3.3.1. Kidney Injury

To prevent renal impairment [32], IPM measures are as follows: 1. Fine-tuning the dosage of all medications, according to the current renal function and pharmacokinetic DDIs, not least with antibiotics. 2. Optimizing blood pressure. 3. The targeted treatment of bradycardia, tachycardia, and arrhythmias. 4. Preventing hypohydration and dehydration. 5. Avoiding single and cumulative nephrotoxic risks from direct drug effects, such as, for example, from NSAIDs monoadministered or even coadministered with ACE inhibitors or sartans and diuretics. 6. The avoidance of single and cumulative indirect nephrotoxic risks from ADRs, such as statins, PPIs, and pharmacodynamic DDIs. 7. The early treatment of bacterial urinary tract infections. 8. The compensation of electrolyte- and acid-base imbalances by timely targeted withdrawal of potentiating drugs and, if compatible with respiratory capacity, the use of bicarbonate. 9. The adherence to standard operating procedures for preventive measures in the administration of contrast media.

3.3.2. QTc Prolongation

Preventive countermeasures to the often unavoidable risk of QTc prolongation are maintenance of serum potassium and magnesium in the high normal range and exclusion of acidosis. Serum magnesium must be monitored during CsA and TAC because of the risk of hypomagnesemia. This can be fatal, e.g., in children, leading to seizures besides the risk of QTc prolongation and torsades des pointes with life-threatening arrhythmias.

3.3.3. The Differential Diagnosis and Follow-up of Cytomegalovirus Infection (CMV)

For the earliest detection of CMV, lymphocyte subpopulation analysis for CD4/CD8 inversion can be a helpful tool, in addition to the standard viral diagnostic measures, such as PCR, etc. in the differential diagnosis of rejection and GvHD [119], and in the assessment of the therapeutic effect in the course of initiated antiviral treatment. With the additional use of this tool and the early initiation of virustatic therapy, we were able to rule out any CMV-related acute or long-term kidney transplant injuries in the pre-valganciclovir prophylaxis era as early as 1992, resulting in a consecutive two-year transplant survival rate of 100% [119,120,121]. It remains to be seen whether valganciclovir prophylaxis might be more harmful in terms of its nephrotoxic potency than its prophylactic indication. And its dose adjustment to the renal function must be considered. This must be consistently acknowledged by the treating physicians in the transplant outpatient setting as well.

3.3.4. Hypogammaglobulinemia

Monitoring for hypogammaglobulinemia as a potential ADR associated with MMF [76], and unfortunately in patients already at increased risk for infectious diseases due to their immunosuppression, should be a standard measure in the transplant patient on MMF. In case of manifested hypogammaglobulinemia, particularly in the context of concomitant infections, immunoglobulin substitution is recommended, and MMF should be discontinued or, e.g., cortisone-bridged to overcome the infection.

3.3.5. Risks in Analgesics and Sedatives

Note that CsA, TAC, SIR, and EVR exposure is reduced by metamizole (dipyrone), which is a CYP3A4 inducer [68]. This requires dose enhancement and TDM of these immunosuppressants, which is often neglected or unfamiliar to treating physicians. The inducing effect can last up to 5 days after the discontinuation of metamizole.

NSAIDs must be avoided in the context of CsA and TAC for risk of severe cumulative nephrotoxic ADR.

Paracetamol (acetaminophen (APAP)), requires caution in hepatic and renal impairment, and is contraindicated in severe liver disease. It requires strict adherence to the dosage according to the prescribing information [85,86]. Avoid intake periods of more than 3 days. Intoxications with paracetamol (APAP) are the second most common cause of liver transplants worldwide [87].

For a wide range of sedatives, e.g., midazolam and lorazepam, also for antipsychotics, such as quetiapine, it is important to know that they are metabolized by CYP4A4, which is inhibited by, e.g., CsA [122], azoles, most macrolides, or amiodarone, with the risk of severe ADRs manifestations, such as myelosuppression in HSCT. The same applies to fentanyl, with the risk of fatal toxicity. Furthermore, because of the risk of severe serotonergic syndrome, it is important to know that the coadministration of SSRI/SNRIs with fentanyl or other serotonergic must always be avoided. The serotonin syndrome may include mental-status changes similar to delirium (e.g., agitation, hallucinations, coma), autonomic instability (e.g., tachycardia, labile blood pressure, hyperthermia), neuromuscular abnormalities (e.g., hyperreflexia, incoordination, rigidity), and/or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Serotonergic opioids are the phenylpiperidine opioids fentanyl, methadone, pethidine, and tramadol as well as morphine analogues oxycodone and codeine [56,123]. This does not apply to non-serotonergic morphine or hydromorphone, which may be used as alternatives.

3.3.6. Life-Threatening Infectious Diseases—Sepsis

The manifestation of severe infectious diseases after transplantation and in the long-term follow-up requires an adequate professional revision of the intensity of the concomitant immunosuppression. Always in consultation with the transplant center, a transient partial reduction or, e.g., bridging with increased cortisone for the temporary withdrawal of CNIs or MMF may save lives.

3.3.7. Surgical Interventions—Wound Healing

In addition to the aforementioned reassessment of the intensity of concomitant immunosuppression required, surgeons in disciplines outside transplantation and unfamiliar with the ADRs of CNIs and mTORIs should be aware that SIR is typically associated with impaired surgical site wound healing. Rates of fluid collections, superficial wound infections, and incisional hernias were significantly higher in SIR patients (47%) when compared to TAC patients (8%), even after adjustment for covariates [4,124]. These risks must be contributed to in any further surgical procedures a transplant patient may undergo, and SIR pausing and bridging with other immunosuppressants needs to be reconsulted with the patient’s transplant center.

3.3.8. Rhabdomyolysis—Statins

Statin drug interactions differ to CsA and TAC. CsA increases the exposure of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors simvastatin, atorvastatin, and lovastatin and/or their pharmacologically active metabolites via the inhibition of intestinal and hepatic CYP 3A4 and P-glycoprotein (P-gp). This is less pronounced in TAC, although there are reports of rhabdomyolysis in TAC with simvastatin/fibrate. The same has been observed with SIR. In addition, the active beta-hydroxyacid form of simvastatin, simvastatin acid, atorvastatin, and their metabolites are substrates of the organic anion-transporting polypeptide protein (OATP), which is also inhibited by CsA. This results in an increased risk of musculoskeletal toxicity and rhabdomyolysis. The concomitant use of simvastatin and CsA is considered contraindicated. Since fluvastatin and pravastatin are not extensively metabolized by CYP3A4, these are alternative agents in patients on CsA. However, it is recommended that these statins as well be started at low doses and titrated cautiously, and patients should be advised to report promptly any unexplained muscle pain, tenderness, or weakness, especially if accompanied by fever, malaise, and/or dark urine. Markedly elevated CK requires withdrawal of the statin. Preferentially, pravastatin at its lowest dose or fluvastatin should be used in any transplantation with concomitant CNIs, especially with CsA [43,59,91,96,100,101,102,122,125].

The risk is synergistically amplified by the very frequent concomitant use of calcium channel blockers, which inhibit both CNI and statin metabolism in the hierarchy described.

3.3.9. Calcium Channel Blockers—DDI-Grading

CsA and TAC are associated with an increased prevalence of hypertension in kidney transplant recipients, partly through renal vasoconstriction and enhancement of tubular reabsorption. In addition to their risks for kidney transplantation, a 4-fold increased risk of death due to end-stage renal disease has been documented in non-kidney organ transplant patients associated with CsA-induced nephrotoxicity. The beneficial effect of calcium channel blockers (CCBs) is to counteract these ADRs after transplantation. A pathophysiologic animal study revealed inflammatory, oxidative, and fibrotic pathways in CsA-induced renal dysfunction, inducing proteinuria and elevations in serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, mesangial expansion, increases in glomerular and tubular type IV collagen expression, and increases in the glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis indices are significantly attenuated up to reversal with the coadministration of CCBs [126]. However, among the different agents available, their varying inhibitory effects on CNI metabolism should be respected. The coadministration of amlodipine with CsA may increase plasma/blood concentrations and the risk of ADRs of both drugs. In the coadministration of amlodipine with TAC, the AUC of TAC may increase by 2.3-fold. TDM of TAC and its dose reduction is important when amlodipine [127] is coadministered. Felodipine can increase the exposure of TAC. With simultaneous use, the TDM of TAC is necessary for the dose reduction of TAC. Felodipine has only a small effect on the blood levels of CsA. But CsA may significantly increase serum felodipine concentrations via the inhibition of CYP3A4 first pass metabolism [128]. Since amlodipine undergoes less first-pass metabolism, it may be considered an alternative. For Lercanidipine, the DDI risk is more pronounced, therefore lercanidipine with TAC should be avoided. The simultaneous administration of lercanidipine and CsA led to a 3-fold increase in lercanidipine plasma levels and a 21% increase in the AUC of CsA. CsA and lercanidipine must not be used together [129]. This risk is less pronounced when given CsA three hours after lercanidipine.

3.3.10. Diarrhea

With many posttransplant drugs, such as with posaconazole, letermovir, etc., the risk of diarrhea manifestation as a potential ADR must always be taken into account. This is in parallel of high relevance in the differential diagnosis and symptomatic assessment of the course and treatment effect of CMV, rejection, GvHD, Clostridium difficile infection, etc.

3.3.11. Loperamide-Induced Cardiotoxicity

Loperamide is a drug that may be added to the transplant patient’s polypharmacy for temporary clinical occasions or on demand. Inhibitors of CYP2C8 or CYP3A4 (TAC less compared to CsA [122]) or the P-gp efflux transporter, such as CsA or TAC, often synergistically with other drugs, may increase the exposure of loperamide in plasma and the central nervous system through the increased systemic exposure of loperamide, and inhibition of P-gp in the blood–brain barrier enhances loperamide entry into the CNS. This may result in enhanced opioid and ADRs. The high plasma levels of loperamide have been associated with serious and fatal cardiac ADRs through QTc prolongation, including arrhythmias, syncope, and cardiac arrest. Concomitant azoles or macrolides or various calcium channel blockers cumulatively increase the loperamide exposure and ADRs furthermore. Patients should be clinically monitored and be instructed to be alert and to consult medical professionals regarding any symptoms of torsade de pointes, such as irregular heartbeat, shortness of breath, dizziness, lightheadedness, fainting, palpitations, or syncope. It was noted that many of the documented loperamide-induced cardiotoxicities required electrical pacing/cardioversion, because the standard antiarrhythmic therapy remained ineffective [130].

3.3.12. Acute Liver Dysfunction

For all patients taking CNIs or mTORIs, as well as other drugs, such as amiodarone, azole antifungals, antivirals, DOACs, etc., liver function monitoring is recommended at individualized, regular intervals, depending on the patient’s condition. Impaired liver function and decreased CYPA4 metabolism, e.g., increase CSA, TAC exposure with subsequent increased nephrotoxicity and the enhanced risk of infections, including CMV. The earliest dose reduction of CNIs and mTORIs and close TDM is essential.

3.3.13. Exchanging CSA or TAC within Different Formulations

Any exchange in CNIs and mTORIs, either in the mode of application or the trading mark, requires close TDM for adequate dose adaption.

3.3.14. Attention Letermovir Metabolism; Letermovir with Voriconazole

Unlike TAC, CsA coadministration with letermovir increases the plasma concentrations of letermovir through the CsA inhibition of the organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B (OATP1B). The oral dose is therefore 240 mg of letermovir once daily with CsA, and 480 mg once daily with TAC [65].

Be aware that the common coadministration with letermovir may decrease the plasma concentrations of drugs that are metabolized by CYP2C9 and/or CYP2C19, e.g., as investigated with voriconazole. Voriconazole peak plasma concentration (Cmax), systemic exposure (AUC), and the concentration at 12 h post-dose (C12hr) decreased by an average of 39%, 44%, and 51%, respectively, when voriconazole 200 mg orally twice daily was coadministered with letermovir 480 mg orally once a day. Dose adjustment may be appropriate with monitoring [65,131].

3.3.15. Monitoring Differentiated ADRs of Immunosuppressants and Integrating Continuous Patient Education

Apart from surgical, patient and graft conditions, the outcome of transplantation depends mainly on the efficacy and optimized dosing of immunosuppressants, which requires strict TDM, but simultaneously on their ADRs. Over the past decades, the various immunosuppressive agents with different combination regimens have been ongoingly investigated to optimize immunosuppression and minimize ADRs.

Unfortunately, especially in renal transplantation, pre-existing metabolic disorders often require polypharmacy before transplantation already. Posttransplant immunosuppressants enhance this problem, e.g., hypertension, new-onset diabetes after transplantation (NODAT) with cortisone and CNIs, more pronounced with TAC compared to CsA, and hyperlipidemia, more prominent with CsA than with TAC, or hyperlipidemia with mTORIs [132,133].

MMF is inert in this context, but given the overall immunosuppressive load, the risk of infection and hypogammaglobulinemia is increased here. And manifest CMV disease itself, as well as HHV6 or BK virus, severely affect graft function. Consecutive antiviral therapy with its own nephrotoxic potential completes this vicious circle. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been reported as a preventive strategy against BK virus viremia and BKV-associated nephropathy [134].

Therefore, the pre- and posttransplant status of each patient, along with its individual risk factors and transplant course, should be clarified as precisely as possible to tailor the immunosuppressive regimen. According to the ADRs of the posttransplant immunosuppressants, the main cause of death after organ transplantation is a cardiovascular event such as stroke or myocardial infarction with a functioning graft, also frequently in HSCT [135]. The inevitable polypharmacy to treat the broad spectrum of cardiovascular risk factors makes IPM all the more necessary, since deprescribing is not possible in this context.

These ADRs and others that impact long-term survival require additional strategic follow-up, including ongoing patient education. As learned from the acute and long-term care, most transplant patients are eager and grateful to be informed about the risks and how to maintain and preserve the graft with their own abilities and engagement. For active patient involvement in the posttransplant period, they need to be educated on remarkable and vulnerable aspects: 1. The optimization of blood pressure and the regular follow-up of blood glucose levels. 2. The risk of increased drug nephrotoxicity as from CNIs with hypohydration, respecting the individual condition and fluid balance. 3. The adherence to consistent immunosuppressive TDM. 4. The communication of any additional medications and supplements prior to their use. 5. The avoidance of any NSAIDs with CNIs. 6. Observations for urinary tract infections or even the initial signs of developing Fournier’s gangrene, as with SGLT2 inhibitors, such as dapagliflozin and empagliflozin. 7. Liver injury caused by unregulated alcohol, food, or dietary supplements, and herbal products, e.g., turmeric-associated liver damage (active ingredient curcumin) as a growing problem [136], or by drugs like paracetamol (acetaminophen). In addition to patient information, it remains essential that clinicians consistently ask for supplements as part of medication reconciliation. The patient always must avoid grapefruit juice in terms of nephrotoxicity via CNI-elevation and St. John’s wort with rejection risk via CNI-decrease. The severe increase in TAC exposure observed with cannabidiol [118] via CYP3A4 inhibition may be indicative of a similar risk for CsA, SIR, EVR and many other drugs, e.g. most statins, calcium channel blockers, sedatives, even some opioids, resulting in serious risk situations. Further research needs to be done here. 8. Regular blood controls to exclude hypomagnesemia caused by CNIs, in addition to hypokalemia, particularly in the setting of prolonged QTc after transplantation, as it is highly prevalent, e.g., in renal transplant patients receiving various classes of immunosuppressive drugs [137], or even cumulative long QTc risks requiring intermittent ECG monitoring for this risk marker of serious arrhythmias and sudden death. 9. To report resorption concerns such as by vomiting or diarrhea from the very beginning. 10. All patients, especially the HSCT patients, must avoid additional risks of myelotoxic ADRs, paricularly in the early phase, and should be monitored and advised to maintain regular, but not overdosed, folic acid and vitamin B12 blood levels, which may be reduced by drugs such as phenytoin, methotrexate, cotrimoxazole, with different interference of folic and folinic acid on the antimicrobial effects to be considered, or vitamin B12 deficiency through proton pump inhibitors, and metformin, respectively. 11. Severe night sweats may be an early indicator of CMV disease and need to be reported immediately [120,121]. Patient empowerment through appropriate information can be a valuable contribution to risk prevention.

In terms of further minimizing cardiovascular risks and events after transplantation, the patient should ideally be instructed and guided to maintain or regain a normal BMI through a healthy lifestyle and individualized training.

4. Discussion

This briefing provides an overdue all-in-one drug safety tool to securely navigate through the individual high-risk context of posttransplant medication. The systematic, methodical intervention to prevent iatrogenic drug-induced injury covers ADRs, DDIs, and contraindications with consistent reference to immunosuppressants. The tabular extracts of the clinically relevant aspects of posttransplant polypharmacy will be a welcome tool for accurate and appropriate medication review according to the successfully implemented IPM. It saves a lot of time in daily routine as it is a breakdown of thousands of SmPC pages. The focus on contraindications, ADRs, and drug-specific warnings, in addition to the usual DDIs, expands the scope of the commonly available DDI tables. Consideration of each of these medication scores in the context of the patient’s condition has already been shown to be impressively associated with successful prevention of the risks of polypharmacy, resulting in highly significant prevention of renal impairment (100%), delirium (decrease 92%; 10-fold reduction), and falls (83%), as well as further improvements after IPM implementation in multimorbid patients within other polypharmacy settings [32,138,139]. The briefing provided for colleagues inside and outside transplantation, who regularly or occasionally care for transplant patients, includes both the extracts of the predominant risks of concerning drugs in posttransplant coadministration and the own implemented preventive countermeasures for critical patient conditions successfully applied within 10 years of IPM and 21 years of TDM in immunosuppressants posttransplant. Since no such comprehensive information is available in the literature, these two items are intended to be a helpful resource toolset in the setting of the complex posttransplant polypharmacy.

Despite decades of continuous progress in organ and stem cell transplantation, the improvement of graft and patient outcomes does not seem to have been further optimized in recent years, e.g., in kidney transplantation [140]. Although the immunosuppressive regimen has been continuously improved according to expertise and research, the problem of polypharmacy, which is constantly increasing, has been largely neglected, with the exception of DDIs for immunosuppressants. Focusing on graft and patient risk through more accurate and comprehensive medication scores could further improve transplant outcomes and quality of life. Polypharmacy has been shown to be associated with poorer quality of life in patients after successful kidney transplantation, and multivariate regression analysis showed that the number of medications independently affected physical function, pain, and social function subscales [141]. It is already known from the pretransplant focus that CKD stage G4/G5 patients and patients on renal replacement therapy have a medication burden far beyond that of the general population, also due to a high burden of comorbidities besides CKD. The authors indicate that a critical approach to medication prescribing could be a first step towards more appropriate medication use [142]. What really happens to ensure this? The issue should be of analogously high importance after a successful transplantation. Analysis of the impact of polypharmacy prior to allogeneic HSCT in older adults demonstrates the relevance of pre-HSCT polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medication and DDIs as important prognostic factors for inferior post-HSCT outcomes or increased hospital length of stay, respectively. These results should support routine pre-HSCT medication review by physicians and pharmacists with the additional goal of appropriate deprescribing [143]. However, the mandatory treatment of the manifest metabolic ADRs of immunosuppressive drugs must be maintained on an optimized level all times.

The provided systematic IPM method adapted to transplantation for the prevention of iatrogenic drug-induced injury has been evaluated with very successful results in other critical polypharmacy settings and has been tested with positive results for its applicability by clinical and community pharmacists. The toolset with the overview and briefing on drug safety/drug therapy safety in transplantation based on real-world IPM enables proactive mitigation of polypharmacy hazards for both the patient and the graft. As a result from daily insights the selection of drugs intentionally addresses frequent patient’s chronic comorbidities, acute illnesses and probably complications in the transplantation course. All of these even abruptly changing intraindividual clinical situations result in varying drug elimination capacities, which are further affected by the additional drugs and their own add-on DDIs and ADRs. The constant focus on drug-induced risks in transplantation and patients on polypharmacy with IPM over 10 years results in a broad real-world expertise of >60,800 medication analyses. To sensitize the transplant team and all other attending physicians on the long-term base for the critical spectrum of the identified predominant risks from DDIs, ADRs, overdosage and contraindications as depicted primarily from the drugs’ SmPCs, interaction and dosing checks, and literature research (medication scores) in context with the very individual patient condition (patient scores) and the therapeutic drug monitoring of immunosuppressants is the aim of this briefing. For best practice in transplantation to improve outcomes, iatrogenic drug-induced injury has to be prevented from the very earliest stage, avoiding any harm to the susceptible transplant organ and the vulnerable, highly immunosuppressed patient with his already preexisting risks and comorbidities.

This is the first briefing overview to consider frequently coadministered polypharmacy in early and long-term transplantation phases. Since the application of the reproducible IPM method only relies on a digital patient record, it does not necessarily require on-site capacities or competencies but can also be performed by instructed physicians or pharmacists from outside. The briefing on the real-world concomitant polypharmacy risks in hospitalized and outpatients experienced in transplantation IPM over 10 years at the University Hospital Halle is to ensure drug therapy safety for further amelioration of acute and long-term graft and patient outcomes with the respect to each very individual patient condition.

The major challenges affecting graft and patient outcomes in solid organ and HSCT immunosuppression are to reduce toxicity while maintaining efficacy and preventing any iatrogenic drug injury. This requires that the risks of over- and underdosing for each individual patient and transplant condition be eliminated as early as possible during the acute and, in solid organ transplantation, the long-term posttransplant phases. However, these risks are not only due to the immunosuppressive regimen, but are also strongly influenced by concomitant polypharmacy. As shown in the table, each drug must be evaluated for its own toxicity in relation to the transplant and the individual patient’s condition, always in the context of the entire medication list. The tabulated risks from ADRs, DDIs, contraindications and additional drug-specific aspects reflect these broad aspects to be considered in clinical practice. To date, there is no comparable adequate overview of concomitantly administered medications within the polypharmacy of transplant patients. Increased morbidity and unexpected outcomes are consequences of DDIs in allogenic HSCT [144]. Mainly lists of DDIs are available, and from the worst end of drug-related injuries up to organ failures, graft loss and patient death, there are numerous case reports, extended by reviews and supplemented lists of drugs, e.g., associated with failure of liver transplantation [12,145,146,147] and furthermore in the outpatient setting DDIs in kidney transplantation [148]. Since the transplant patient often suffers from multimorbidity with unavoidable polypharmacy being already on pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD), as it may also be the result in a renal transplant, a rigorous focus on the exclusion of any iatrogenic, additional drug-induced decline in renal function is essential in the context of the CNI’s own nephrotoxicity and the vulnerability of the kidney transplant. CsA and TAC make it all the more important to focus on optimizing this multimedication process, particularly for enhanced risks of ADRs and DDIs with the pre-impaired drug degrading or eliminating organs [149] and further afflicted vulnerable transplant patients.

It is of great concern that there remain transplant patients who are coadministered NSAIDs with all their own associated ADRs and pharmacodynamically increased cumulative risk of nephrotoxicity from DDI with CNIs [150,151,152]. We even find patients on triple whammy, the concomitant use of diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (sartans) with NSAIDs, which per se is associated with high risk of acute renal failure [153], independent of the type of organ transplant or HSCT and further enhanced by CsA or TAC. Diuretics-associated kidney injury leading to AKI has been documented with pathological details showing vacuolar degeneration of tubular epithelial cells as a common lesion induced mainly by loop diuretics, with age being a predictive factor for incomplete recovery and all-cause mortality, and changes being more severe at high doses [154]. The coadministration of loop diuretics and HCT, preferably xipamide, as IPM-targeted in individual cases to benefit from transient sequential nephron blockade, is also known to further improve diastolic function in patients with resistant hypertension [155,156]. It allows the dose of the single diuretic to be reduced but should be time-limited and requires parallel serum electrolyte monitoring.

Study results remain controversial regarding the effects of allopurinol on CKD. Hyperuricemia, linked with inflammation but also with progression of renal and cardiovascular disease, has been effectively treated with allopurinol, with a beneficial effect on all these conditions [157]. A recently published large RCT in the United Kingdom in patients aged ≥60 years showed no difference in the primary outcome of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death between participants randomized to allopurinol therapy and usual care [158]. However, treated patients had relatively low mean serum uric acid concentrations at baseline, and the association between allopurinol-induced changes in serum uric acid concentrations and outcomes was not confirmed [159]. From own IPM findings in the serum uric acid-lowering drugs, when indicated in patients with symptomatic hyperuricemia, allopurinol often failed to be dose adjusted in advanced CKD. Similarly for febuxostat, its exposure is known to be increased 2–4-fold in severe renal disease with eGFR < 30 mL/min, requiring withdrawal due to insufficient safety yet, and it is not recommended in organ transplant patients or in patients with ischemic heart disease or decompensated heart failure [160], aspects that are also largely ignored according to our IPM analyses. Despite broad experimental and epidemiologic evidence for hyperuricemia as a risk factor for CKD, the overall evidence for the therapeutic effect of allopurinol is insufficient [161]. The KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease states: “Hyperuricemia 3.1.20: There is insufficient evidence to support or refute the use of agents to lower serum uric acid concentrations in people with CKD and either symptomatic or asymptomatic hyperuricemia to delay progression of CKD. (Not graded)” [162] (p. 10).

In addition, there are often serious acute risks from overdosing, especially with antibiotics [32], which are further increased without adequate parallel hydration. Also statins in high doses or by DDI-enhanced exposure, which could affect the kidney graft function in the acute and long-term survey [163,164,165,166,167], are most often observed not to be dose adjusted. Respecting the DDI with TAC and CsA, pravastatin should be preferred, although dose adjustments are required. The same is true for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which are mostly overdosed; especially a prophylactic dose of pantoprazole should not exceed 20 mg per day. However, the results on the renal risks of PPIs are controversial and have been abandoned, for example, in renal transplant patients [81]. Although there is evidence that PPI use is associated with an increased risk of CKD in terms of incident CKD, progression of CKD and renal failure [82], we often find non-indicated long-term prescriptions. A graded increase in risk with higher doses and longer duration of PPI therapy has been described [82]. Associations between PPI use and the risk of acute interstitial nephritis and acute kidney injury (AKI) have been reported, particularly among hospitalized patients. A direct pathway to indolent chronic kidney injury has been suggested [82]. The demonstrated temporal association between exposure to PPIs and the occurrence of AIN may strengthen a causal relationship [83]. As PPI use has been associated with an increased risk of chronic kidney injury even in the absence of AKI, relying on AKI as a precautionary sign may not be sufficient to reduce the risk of CKD in PPI users [84].

A widely cited review of ADRs from 25 years ago recognized this common clinical problem and stated that clinician vigilance in detecting, diagnosing, and reporting ADRs is important for ongoing drug safety monitoring [168]. So do we really consistently monitor for the elimination of serious ADRs? In the posttransplant polypharmacy setting, specific pharmacovigilance for each drug in this context presents an even more complex challenge, as the problem may be compounded by increased drug exposure due to pharmacokinetic DDIs or enhanced effects related to cumulative pharmacodynamic drug effects and ADRs. Without knowledge of the major ADRs and DDIs of each drug, the problem becomes almost insurmountable. Another intensive review of the factors influencing the development of ADRs revealed that various risk factors such as age, renal and hepatic function, drug dose and frequency play a key role [169]. The additional susceptibility of the immunosuppressed and often multimorbid transplant patient may increase the potential for influence.

For the care of transplant patients, there are lists of DDIs, some of which have been taken from books, such as those on DDIs in the drug therapy of heart transplant recipients [170,171]. The table presented here prefers the drug-specific SmPC in its most recent and more complete version, especially since it also includes the ADRs and contraindications of the drugs. This is of analogous additional importance. The pioneering teams of Calne in kidney transplantation [172] and Starzl in early liver transplantation were already struggling with the dose-dependent severe nephrotoxicity of CsA, and Starzl advocated some dose reduction to overcome this effect without liver transplant rejection [173]. Despite decades later with the availability of other immunosuppressants, these CNI risks of nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity remain unchanged and often go unrecognized in patients without adequate prevention and close monitoring. In the long term, this increases chronic graft failure and may be partly responsible for the long-term outcome of renal allografts worldwide. In this context, the coadministration of nephrotoxic agents that should be avoided, such as NSAIDs, remains a concern for the treating physician. Patients need to be educated about these risks in the outpatient setting. Chronic CsA nephrotoxicity is the second most important diagnosis responsible for late graft failure. Clinicopathological CSA-associated arteriolopathy (CAA) is a well-known lesion of chronic CSA nephrotoxicity [174]. It was the Mihatsch group, among others, that consistently focused on the pathological findings over decades. In addition, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FGS) lesions accompanying CAA have been considered as CSA-associated glomerulopathy. Importantly, intraindividually variable CsA predose was evaluated as an independent predictor of chronic rejection and graft loss. Thus, the authors emphasize the need for therapeutic drug monitoring, ideally 2 h (C2) CsA measurements, but also for patient’s adherence instructions and for controlling consistent CsA delivery using new generic formulations [175]. Intraindividual variability becomes apparent, particularly abruptly from the onset of pharmacokinetic DDIs with changing concomitant medications requiring earliest adjustment and close TDM.

All these data from different perspectives, such as the timing and frequency of TDM, the knowledge of drug-associated pathological injuries, the variants in different generic drug formulations, the informed patient, and, of major importance, the broad spectrum of ADRs, DDIs, and contraindications underline that the more the treating physician is sensitized, the greater the benefit for the graft and the patient’s outcome.

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

IPM requires a holistic clinical view of the patient’s entire medication regimen. The educational background of the designing and performing IPM internist with advanced education in clinical pharmacology also covers a broad spectrum of expertise and successful engagement in improving outcomes in clinical transplantation [119,120,121,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185] and the qualification as Distinguished Educator of the Transplantation Society Academy, thus ensuring experience in a broad professional transplantation context. In addition to 21 years of daily experience in TDM of immunosuppressants in transplantation, this allows a highly patient-individualized focus for a comprehensive evaluation. The greatest achievement of her former kidney transplant team at the University of Bonn was a two-year consecutive survival rate of 100% for kidney transplants already in the 1992 [121]. The tabulated risks are mainly extracted from updated SmPCs, and therefore depend on the author’s own experience in terms of what is covered and what is excluded. It is important to outline that the task of reducing SmPCs from 10 up to even more than 100 pages for one drug means that, for each drug, there is a deliberate exclusion of other relevant aspects, such as pregnancy, lactation, pediatric aspects, hypersensitivity, intolerance related to congenital disorders, among others. Therefore, the table is not a complete replacement for the SmPCs. The list of drugs is not exhaustive with respect to contemporaneously coadministered drugs in transplantation. In particular, the DDIs referenced in the SmPCs always remain incomplete because they are never extensively studied in vitro and only rudimentarily, if at all, in vivo. And most strikingly, there are even approved drugs that still lack degradation information, the indispensable prerequisite for the analysis of pharmacokinetic DDIs. In very rare and adequately justified off-label cases to overcome life-threatening conditions of patients, individual drug indications or contraindications from the SmPCs are intentionally not adhered to. Also rarely, the spectrum of use and dosing within the limits of impaired renal function may change in the course of post-marketing experience with a drug. These upcoming cases and highly individualized dosing cannot be covered in this overview. With the exception of grapefruit juice, St. John’s wort, and cannabis, the tabularized medicinal items presented do not cover foods and substances related to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), such as dietary supplements, herbs, and other manufactured ingredients, although they have been shown to have a further relevant impact, especially in outpatients, as in cancer therapy, with a likelihood of interactions as high as 37% in the case of CAM supplements, and 29% of all patients for foods [186,187]. There is no reference to CYP3A4, CYP3A5, or MDR-1 genotype metabolism for additional pharmacokinetic genotype-based individualized dosing aspects of, e.g., CSA or TAC in genetic polymorphism that also affects outcomes [188].

6. Conclusions and Outlook

To improve drug safety and patient and transplant outcomes in the context of polypharmacy requires the implementation of standardized methods that refer to all relevant risks, resulting from a single drug administration as well as from its coadministration within a broad spectrum of further medications and the individual patient condition itself. Since the range of ADRs and DDIs is immense and the study of large numbers of SmPC pages for each drug is almost unmanageable in daily routine, the provided overview could be a helpful tool in practice, other than the simultaneously available computerized DDI checks and DDI tables, which do not address specifically ADRs and individual patient-condition-related contraindications or individual requirements in multimorbidity and polypharmacy. In addition to improving long-term graft survival, the presented briefing also addresses the recently documented decline in 5-year kidney transplant outcomes, indicating a remaining unmet demand for innovation in the early transplant phase as well [140].

The outlook is to integrate the comprehensive IPM findings, such as the provided overview, into a forthcoming digital IPM support system that is standardized and compatible with the use of the transplant patient’s electronic health record and aims to be accessible and understandable for all healthcare professionals, the patients themselves, and their families. The entirely computerized identification of polypharmacy risks through the defined and implemented medication scores to the individual patient and his/her most currently updated health status, organ functions, and comedications based on the electronic health record, as performed by the IPM, will be of great benefit not only to the transplant field, as for serious risks observed in the contemporary real-world polypharmacy, the highly preventive effect of IPM has been documented by the first published IPM results [32,138,139]. There is no database integrated with an electronic health record system to perform this IPM in a holistic, elaborate manner, including the defined encompassing patient and medication scores. The far-reaching concerning iatrogenic medication risks arising from today’s increasing polypharmacy require earliest elimination.

The intentionally comprehensive IPM concept for medication safety meets the demands of the global challenges continually being addressed by the WHO: “A comprehensive medication review is a multidisciplinary activity whereby the risks and benefits of each medicine are considered … It optimizes the use of medicines for each individual patient…Polypharmacy can put the patient at risk of adverse drug events and drug interactions when not used appropriately” [189] (p. 7).

This second paper, following the first IPM/TDM design paper, is to provide the additional corresponding practical toolset to cover the enormous challenges of the defined medication scores that require awareness and briefing. It is intended as an informative all-in-one resource for transplantologists and subsequent attending physicians, who often come from different disciplines and are unfamiliar with the risks of polypharmacy.

Our human and professional ethics, the donor, the transplant, and the recipient, as well as the shortage of organs, obligate us to continue to promote optimal patient and transplant care.

Funding

I gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the German Research Foundation’s (DFG) Open Access Publishing funding program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The presentation was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional ethics committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. According to the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as no ethical concerns were raised about the anonymized data and nonperson presentation. Patient interests worthy of protection are not affected by the completely anonymized data obtained for clinical purposes from routine care.

Informed Consent Statement

According to the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, the requirement for informed consent was waived for the entirely anonymized evaluation and presentation.

Data Availability Statement

There are no datasets generated and analyzed for the concept presented.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my medical colleagues at the University Hospital Halle (UKH) for their straightforward interdisciplinary digital cooperation based on the electronic patient record for individual medication and polypharmacy management, with the successful implementation of IPM and continuous and intensive collaboration to optimize patient and drug safety at the UKH. I am also grateful to the physicians from other hospitals and, across the sector, to the primary care physicians, nurses, and pharmacists for their interest in IPM by attending my advanced education IPM seminars and the interprofessional IPM workshops.

Conflicts of Interest

U.W. received honoraria for scientific lectures on risks of polypharmacy from Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer. U.W. is member of “Deutsche Transplantationsgesellschaft“ and the Transplantation Society. She obtained the “Distinguished Educator” certificate of the Transplantation Society Academy 2014 and was awarded, partly with financial project supports, the Poster Prize for Patient Safety in Drug Therapy 2018, Lohfert Prize 2020 for Measurable Innovations to Improve Patient Safety, German Medical Award Medical Management 2020, cdgw-Future Award “Zukunftspreis Gesundheitswirtschaft” 2021, and Digital Female Leader Award Health 2021 for the effectiveness and efficacy of the Individual Pharmacotherapy Management. U.W receives lecture fees from Bonn and Heidelberg Universities for student teaching in the master’s degree for continuing education in “Drug Therapy Safety Management”.

References

- Sandimmun Concentrate for Solution for Infusion 50 mg/mL, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited, SmPC, Updated emc 15 September 2023. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1036/smpc#gref (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Prograf 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 5 mg Hard Capsules, Astellas Pharma Co., Ltd., SmPc 5 December 2022. Available online: https://www.medicines.ie/medicines/prograf-capsules-33450/spc (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Rapamune 1 mg Coated Tablets. Summary of Product Characteristics, Updated emc 2 August 2021|Pfizer Limited. Rapamune 1 mg Coated Tablets—Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)—Print Friendly—(emc). Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10398/smpc#gref (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Rapamune 2 mg Coated Tablets, Pfizer Limited. SmPC, Updated emc July 2021. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/10399/smpc#about-medicine (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Marty, F.M.; Lowry, C.M.; Cutler, C.S.; Campbell, B.J.; Fiumara, K.; Baden, L.R.; Antin, J.H. Voriconazole and sirolimus coadministration after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006, 12, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P.P.; Manivannan, J.; John, G.T.; Jacob, C.K. Sirolimus and ketoconazole co-prescription in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 2004, 77, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, J.J. Exposure-response relationships and drug interactions of sirolimus. AAPS J. 2004, 6, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afinitor 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg Tablets, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd., SmPC, Updated emc 12 July 2022. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6658/smpc#gref (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Wolf, U. A Drug Safety Concept (I) to Avoid Polypharmacy Risks in Transplantation by Individual Pharmacotherapy Management in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Immunosuppressants. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.W.; Galanko, J.A.; Shrestha, R.; Fried, M.W.; Watkins, P. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure from drug induced liver injury in the United States. Liver Transplant. 2004, 10, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapowicz, G.; Fontana, R.J.; Schiødt, F.V.; Larson, A.; Davern, T.J.; Han, S.H.; McCashland, T.M.; Shakil, A.O.; Hay, J.E.; Hynan, L.; et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Pérez, M.; González-Grande, R.; García-Cortés, M.; Andrade, R.J. Drug-Induced Liver Injury after Liver Transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2020, 26, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethesda, M.D. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]; Updated 23 November 2023; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yasrebi-de Kom, I.A.R.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Abu-Hanna, A.; Schut, M.C.; de Lange, D.W.; van Roon, E.N.; de Jonge, E.; Bouman, C.S.C.; de Keizer, N.F.; Jager, K.J.; et al. Acute kidney injury associated with nephrotoxic drugs in critically ill patients: A multicenter cohort study using electronic health record data. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, C.A. Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 78, 743–750. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, U.; Klein, B.; Miersch, W.D.; Molitor, D.; Klehr, H.U. Dilemma: Maintenance therapy enhances sclerogenic risk profile. Transplant. Proc. 1996, 28, 3227–3230. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, U.; Ferber, J.; Heimbach, D.; Klehr, H.U. Manifestation of metabolic risk factors after renal transplantation: I: Association with long-term allograft function. Transplant. Proc. 1995, 27, 2048–2049. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, U.; Ferber, J.; Heimbach, D.; Klehr, H.U. Manifestation of metabolic risk factors after renal transplantation: II. Impact of maintenance therapy. Transplant. Proc. 1995, 27, 2050–2051. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, U.; Ferber, J.; Klehr, H.U. Manifestation of metabolic risk factors after renal transplantation—II. Impact of maintenance therapy. 25. Kongress der Gesellschaft für Nephrologie, Zürich, September 1994. Kidney Int. 1995, 47, 979. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, U.; Ferber, J.; Heimbach, D.; Klehr, H.U. Manifestation of metabolic risk factors after renal transplantation: III. Impact on cerebrocardiovascular complications. Transplant. Proc. 1995, 27, 2052–2053. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, U.; Brensing, K.A.; Klehr, H.U. Chronic allograft destruction vs. chronic allograft rejection. Transplant. Proc. 1994, 26, 3119–3120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halloran, P.F. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2715–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosing. Arzneimitteldosierung bei Niereninsuffizienz. 1998–2023 Abt. Klinische Pharmakologie & Pharmakoepidemiologie, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg. Available online: https://dosing.de/nierelst.php/ (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Stanford Health Care Antimicrobial Dosing Reference Guide. ABX Subcommittee Approved: 12/2022. Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee Approved 1/2023. Available online: https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/bugsanddrugs/documents/antimicrobial-dosing-protocols/SHC%20Antimicrobial%20Dosing%20Guide.pdfhttps://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/bugsanddrugs/documents/antimicrobial-dosing-protocols/SHC%20Antimicrobial%20Dosing%20Guide.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Renal Dose Adjustment Guidelines for Antimicrobials. CRRT Dosing Recommendations. Prepared by Peitz, G.; Rolek, K.; Van Schooneveld, T. Approved by Antimicrobial Stewardship Program: June 2016. Available online: https://www.unmc.edu/intmed/_documents/id/asp/dose-renal-dose-adjustment-guidelines-for-antimicrobial.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Drugs.com. Drug Interaction Checker. Check for Multi-Drug Interactions Including Alcohol, Food, Supplements & Diseases. Available online: https://www.drugs.com/drug_interactions.html (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- DrugBank Online. Interaction Checker. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drug-interaction-checker#results (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Hesselink, D.A.; van Schaik, R.H.; van der Heiden, I.P.; van der Werf, M.; Gregoor, P.J.; Lindemans, J.; Weimar, W.; van Gelder, T. Genetic polymorphisms of the CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and MDR-1 genes and pharmacokinetics of the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 74, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Yin, L.; Yang, J.; Sun, L. Correlation between gene polymorphism and blood concentration of calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplant recipients: An overview of systematic reviews. Medicine 2019, 98, e16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, M.; Pastor-Anglada, M. Insights into the Pharmacogenetics of Tacrolimus Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, U.; Eckert, S.; Walter, G.; Wienke, A.; Bartel, S.; Plontke, S.K.; Naumann, C. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in geriatric patients and real-life associations with diseases and drugs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, U.; Ghadir, H.; Drewas, L.; Neef, R. Underdiagnosed CKD in Geriatric Trauma Patients and Potent Prevention of Renal Impairment from Polypharmacy Risks through Individual Pharmacotherapy Management (IPM-III). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aciclovir 200 mg Tablets, Wockhardt UK Ltd., SmPC, Updated emc 21 September 2016. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2353/smpc#gref (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Allopurinol Tablets BP 100 mg Aurobindo Pharma—Milpharm Ltd. SmPC, Updated emc 7 February 2022. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7004/smpc#gref (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Amiodarone Hydrochloride 200 mg Tablets. Summary of Product Characteristics, Updated emc 20 February 2023|Ennogen Pharma Ltd. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13964/smpc/print (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Amlovie 10—10 mg Amlodipine, Dafra Pharma GmbH, Updated SmPc January 2019. Available online: https://www.dafrapharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/AMLOVIE-10-SmPC-2019-revkvh.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- AmBisome Liposomal 50 mg Powder for Dispersion for Infusion Gilead Sciences Ltd. SmPC, Updated emc October 2019. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1022/smpc#gref (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Eliquis 2.5 mg Film-Coated Tablets. Summary of Product Characteristics, Updated 23 June 2023—Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer EEIG. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/eliquis-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Aprepitant 80 mg and 125 mg Hard Capsules. Summary of Product Characteristics, Updated emc 14 September 2020|Sandoz Limited. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/11726/smpc/print (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- EMEND 125 mg Hard Capsules, 80 mg Hard Capsules, Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/emend-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Aspirin 75 mg Dispersible Tablets, Actavis UK Ltd., Updated SmPC September 2013. Available online: https://www.hpra.ie/img/uploaded/swedocuments/LicenseSPC_PA0176-015-003_23092013104042.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Acetylsalicylzuur Ratiopharm 500 mg, Tablette, Ratiopharm GmbH, SmPC 15 February 2022. Available online: https://www.geneesmiddeleninformatiebank.nl/smpc/h126642_smpc_en.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Atorvastatin Tablets 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg. Atorkey (Trade Name) Summary of Product Characteristics Updated March 2021, Aurobindo Pharma Ltd., Unit-XV. Available online: https://www.tmda.go.tz/uploads/1620043518-T20H0069SmPCv1.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Azithromycin 500 mg Tablets. Summary of Product Characteristics, Updated emc 9 June 2022|Sandoz Limited. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6541/smpc/print (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Buprenorphine 8 mg Sublingual Tablets, Ranbaxy (UK) Limited a Sun Pharmaceutical Company, SmPC, Updated emc 2 June 2021. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2050/smpc#gref (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Tegretol® 100 mg, 200 mg and 400 mg Tablets, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited, SmPC, Updated emc 25 May 2022. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1040/smpc#gref (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Vistide—Cidofovir Equivalent to 375 mg/5 mL (75 mg/mL) Cidofovir Anhydrous. Gilead Sciences Limited, UK, SmPC. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/1997/199704232996/anx_2996_en.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Ciprofloxacin 2 mg/mL, Solution for Infusion. SmPC Updated 16 September 2019—Baxter Holding B.V. Available online: https://www.hpra.ie/img/uploaded/swedocuments/Licence_PA2299-034-001_16092019092404.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Citalopram 20 mg Tablets. Zentiva Pharma UK Limited. SmPC, Updated emc 23 June 2023. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5160/smpc#gref (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Clarithromycin 500 mg Powder for Solution for Infusion. Ibigen S.r.l., SmPC, Updated emc 4 October 2023. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8825/smpc#about-medicine (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Clopidogrel 75 mg Film-Coated Tablets, Aurobindo Pharma—Milpharm Ltd. SmPC, Updated emc 4 August 2022. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5207/smpc#gref (accessed on 19 October 2023).

- Prednisolone 5 mg Tablets, Wockhardt UK Ltd., SmPC Updated emc 13 May 2021. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2427/smpc#gref (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Jardiance 10 mg and 25 mg Film-Coated Tablets, Empaglifozin. Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, SmPC, Updated emc September 2023. Available online: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5441/smpc#gref (accessed on 23 October 2023).