Examining the Myth of Prescribed Stimulant Misuse among Individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Eligibility Criteria

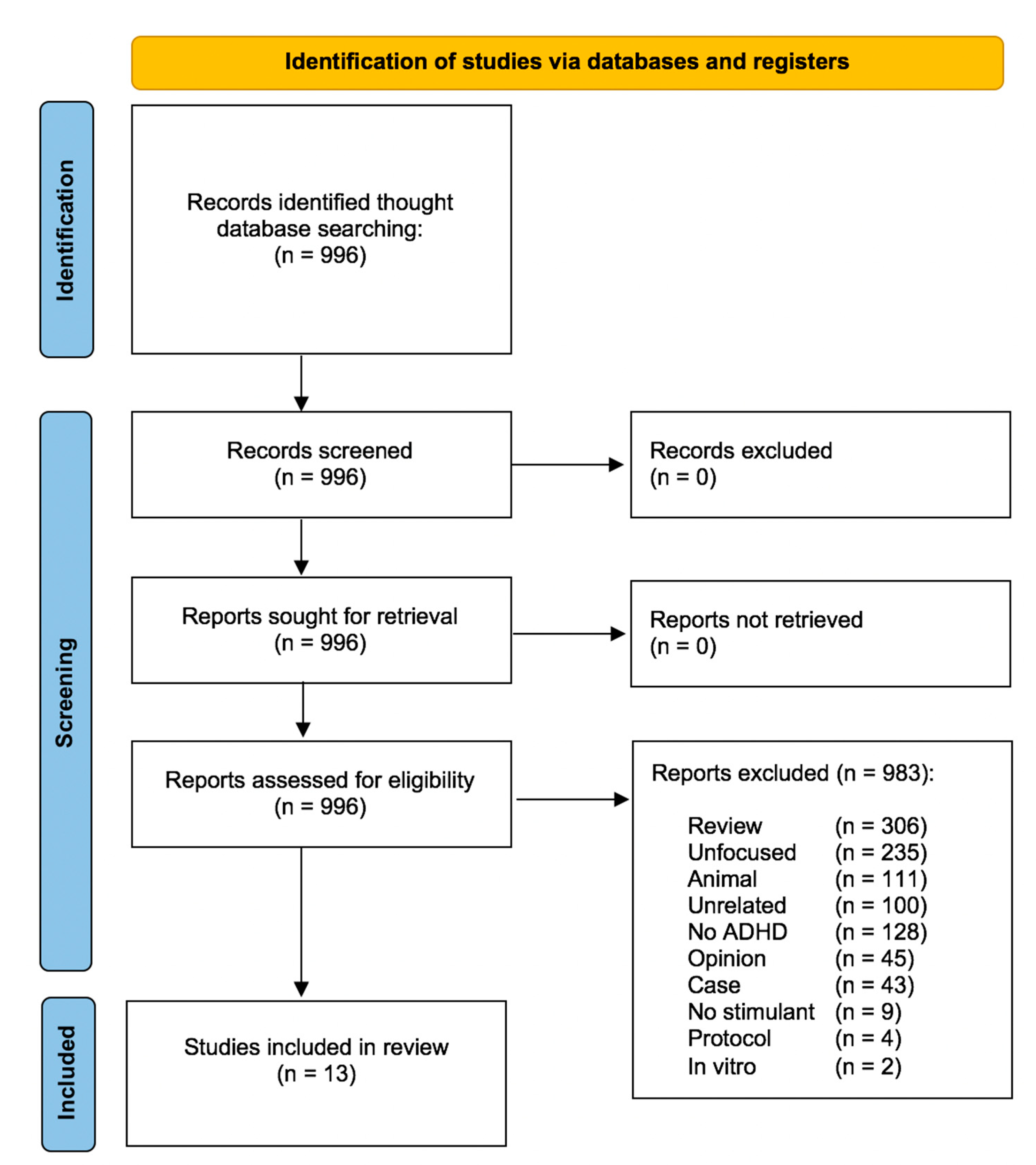

4.2. Search Strategy and Selection of Studies

4.3. Data Extraction

4.4. Primary and Secondary Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual Research Review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zha, M.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Rudan, I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 04009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Blanco, C.; Wang, S.; Greenhill, L. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulants in the United States. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.R.; Man, K.K.C.; Bahmanyar, S.; Berard, A.; Bilder, S.; Boukhris, T.; Bushnell, G.; Crystal, S.; Furu, K.; KaoYang, Y.-H.; et al. Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: A retrospective observational study using population-based databases. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, S.; Adamo, N.; Del Giovane, C.; Mohr-Jensen, C.; Hayes, A.J.; Carucci, S.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Tessari, L.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, W.; Han, B.; Blanco, C.; Johnson, K.; Jones, C. Prevalence and Correlates of Prescription Stimulant Use, Misuse, Use Disorders, and Motivations for Misuse Among Adults in the United States. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, K.; Flory, K.; Humphreys, K.L.; Lee, S.S. Misuse of stimulant medication among college students: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 18, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arria, A.M.; Garnier-Dykstra, L.M.; Caldeira, K.M.; Vincent, K.B.; O’Grady, K.E.; Wish, E.D. Persistent nonmedical use of prescription stimulants among college students: Possible association with ADHD symptoms. J. Atten. Disord. 2011, 15, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiner, D.L.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Costello, E.J.; Hoyle, R.H.; McCabe, S.E.; Swartzwelder, H.S. Motives and perceived consequences of nonmedical ADHD medication use by college students: Are students treating themselves for attention problems? J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 13, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussault, C.L.; Weyandt, L.L. An examination of prescription stimulant misuse and psychological variables among sorority and fraternity college populations. J. Atten. Disord. 2013, 17, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdi, G.; Weyandt, L.L.; Zavras, B.M. Non-Medical Prescription Stimulant Use in Graduate Students: Relationship with Academic Self-Efficacy and Psychological Variables. J. Atten. Disord. 2014, 20, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyandt, L.L.; Janusis, G.; Wilson, K.G.; Verdi, G.; Paquin, G.; Lopes, J.; Dussault, C. Nonmedical prescription stimulant use among a sample of college students: Relationship with psychological variables. J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 13, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, F.R.; Evans, S.M.; Brooks, D.J.; Kalbag, A.S.; Garawi, F.; Nunes, E.V. Treatment of methadone-maintained patients with adult ADHD: Double-blind comparison of methylphenidate, bupropion and placebo. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006, 81, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae-Clark, A.L.; Brady, K.T.; Hartwell, K.J.; White, K.; Carter, R.E. Methylphenidate transdermal system in adults with past stimulant misuse: An open-label trial. J. Atten. Disord. 2011, 15, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, Y.; Långström, N.; Larsson, H.; Lindefors, N. Long-term treatment outcome in adult male prisoners with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Three-year naturalistic follow-up of a 52-week methylphenidate trial. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 35, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.M.; Tulak, F.; Troncale, J. Prevalence and characteristics of adolescent patients with co-occurring ADHD and substance dependence. J. Addict. Dis. 2004, 23, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darredeau, C.; Barrett, S.P.; Jardin, B.; Pihl, R.O. Patterns and predictors of medication compliance, diversion, and misuse in adult prescribed methylphenidate users. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 22, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, G.M. Abuse of medications employed for the treatment of ADHD: Results from a large-scale community survey. Medscape, J. Med. 2008, 10, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Looby, A.; Earleywine, M. Prescription stimulant expectancies in recreational and medical users: Results from a preliminary expectancy questionnaire. Subst. Use Misuse 2009, 44, 1578–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, B.S.G.; Joseph, H.M.; Kipp, H.L.; Lindstrom, R.A.; Pedersen, S.L.; Kolko, D.J.; Bauer, D.J.; Subramaniam, G.A. Adolescents treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in pediatric primary care: Characterizing risk for stimulant diversion. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2021, 42, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilens, T.E.; Gignac, M.; Swezey, A.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Biederman, J. Characteristics of adolescents and young adults with ADHD who divert or misuse their prescribed medications. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejerot, S.; Rydén, E.M.; Arlinde, C.M. Two-year outcome of treatment with central stimulant medication in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A prospective study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lensing, M.B.; Zeiner, P.; Sandvik, L.; Opjordsmoen, S. Adults with ADHD: Use and misuse of stimulant medication as reported by patients and their primary care physicians. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2013, 5, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkeli, P.J.; Vicente, R.P.; Mulinari, S.; Johnell, K.; Merlo, J. Overuse of methylphenidate: An analysis of Swedish pharmacy dispensing data. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, C.; Soeiro, T.; Lacroix, C.; Jouve, E.; Micallef, J.; Frauger, E. Augmentation de l’abus de méthylphénidate: Repérage et profils sur 13 années [Increasing methylphenidate abuse: Tracking and profiles during 13-years]. Thérapie 2022, 77, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen, M.; Halmøy, A.; Faraone, S.V.; Haavik, J. Long-term efficacy and safety of treatment with stimulants and atomoxetine in adult ADHD: A review of controlled and naturalistic studies. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczenski, R.; Segal, D.S. Exposure of adolescent rats to oral methylphenidate: Preferential effects on extracellular norepinephrine and absence of sensitization and cross-sensitization to methamphetamine. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 7264–7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Michaelides, M.; Baler, R. The Neuroscience of Drug Reward and Addiction. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 2115–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, J. Compliance with Stimulants for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. CNS Drugs 2003, 17, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, K.; Sumiya, F. Tolerance to Stimulant Medication for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Literature Review and Case Report. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, S.P.; Kroutil, L.A.; Williams, R.L.; Van Brunt, D.L. The nonmedical use of prescription ADHD medications: Results from a national Internet panel. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2007, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollins, S.H.; Rush, C.R.; Pazzaglia, P.J.; Ali, J.A. Comparison of acute behavioral effects of sustained-release and immediate-release methylphenidate. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1998, 6, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, T.J.; Biederman, J.; Ciccone, P.E.; Madras, B.K.; Dougherty, D.D.; Bonab, A.A.; Livni, E.; Parasrampuria, D.A.; Fischman, A.J. PET Study Examining Pharmacokinetics, Detection and Likeability, and Dopamine Transporter Receptor Occupancy of Short- and Long-Acting Oral Methylphenidate. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepis, T.; Krishnan-Sarin, S. Characterizing adolescent prescription misusers: A population-based study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoglund, C.; Brandt, L.; D’Onofrio, B.; Larsson, H.; Franck, J. Methylphenidate doses in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and comorbid substance use disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilens, T.E.; Adler, L.A.; Adams, J.; Sgambati, S.; Rotrosen, J.; Sawtelle, R.; Utzinger, L.; Fusillo, S. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: A systematic review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, S.; Darke, S. The diversion and misuse of pharmaceutical stimulants: What do we know and why should we care? Addiction 2012, 107, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.; Guenter, D. Treatments for ADHD in adults in jails, prisons and correctional settings: A scoping review of the literature. Health Justice 2023, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, B.S.G.; Kipp, H.L.; Joseph, H.M.; Engster, S.A.; Harty, S.C.; Dawkins, M.; Lindstrom, R.A.; Bauer, D.J.; Bangalore, S.S. Stimulant Diversion Risk Among College Students Treated for ADHD: Primary Care Provider Prevention Training. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicola, M.; Sala, L.; Romo, L.; Catalano, V.; Even, C.; Dubertret, C.; Martinotti, G.; Camardese, G.; Mazza, M.; Tedeschi, D.; et al. Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in major depressed and bipolar subjects: Role of personality traits and clinical implications. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 264, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nicola, M.; Callovini, T.; Pepe, M.; De Mori, L.; Montanari, S.; Bartoli, F.; Carrà, G.; Sani, G. Substance use disorders in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The role of affective temperament. J. Affect. Disord. 2024; 354, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Population | Drugs | ADHD Assessment | Study Design | Prevalence and Modality of Stimulant Diversion and Abuse/Misuse | Conclusion and Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult sample | ||||||

| Levin et al., 2006 [13] | Total sample of 98 methadone-maintained patients with ADHD (56♂, 42♀; age = 39 ± 7) treated with Mph (N = 32, age = 40 ± 6; start medication age = 40 ± 6), bupropion and placebo. 53% of the sample had co-occurrent cocaine dependence/abuse | Mph sustained release | WURS, AARS and clinical interview | DB Plc-controlled 12-week clinical trial comparing the efficacy of Mph and bupropion to placebo on ADHD symptoms | No evidence that stimulant medication was diverted, misused or abused during 12-week study | Sustained-release Mph and sustained-release bupropion did not demonstrate a significant advantage over placebo in alleviating ADHD symptoms. The use of sustained-release Mph can be considered safe in terms of potential misuse, and there was no evidence of it worsening cocaine use |

| Wilens et al., 2006 [21] | Total sample of 98 medicated subjects (65♂, 33♀; age = 20.8 ± 5.1), among them 55 individuals (45♂, 10♀; age = 21.8 ± 5.7.; start medication age = NA) reported current prescription for ADHD medication | Stimulant medication | DSM-III-R | Longitudinal 10 years case–control family study to evaluate the prevalence and correlates of ADHD stimulant diversion and misuse | Among the ADHD sample (N = 55), 11% reported selling medications and 22% reported misusing their medications taking excessive amounts or misuse it in order to “get high”. Individuals with conduct or SUD accounted for the misuse and diversion | Individuals with ADHD, especially those without conduct or SUD, use their medications responsibly. However, closely monitoring medication use and choosing medications with low risk of diversion or misuse in ADHD individuals with comorbid conduct or SUD is recommended |

| Darredeau et al., 2007 [17] | Total sample of 66 individuals (35♂, 31♀; age = 22.3 ± 8.7; start medication age = 21.6 ± 10.4) with prescribed ADHD medications | Mph | ADHD symptom checklist based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria | Observational cross-sectional study to investigate adherence, diversion, and misuse of stimulant | 44% of the of the total sample diverted their medication. Among them, 97% reported giving away their medication, 17% reported selling it, and 14% reported doing both. 29% of the total sample reported misusing their medications. Of those who reported ever misusing their medication, 84% reported oral misuse, 74% reported intranasal use, and 11% reported smoking it. None reported intravenous use. In addition, 68% of Mph misusers reported deliberately mixing Mph with alcohol and/or illicit substances | Noncompliance with medication, diversion, and misuse are prevalent and interconnected. A key distinguishing factor between individuals who misuse Mph and those who do not, seems to be their history of substance use. In this light, closely monitor prescriptions for these individuals are recommended. |

| Looby and Earleywine, 2009 [19] | Total sample of 157 individuals (44♂, 113♀; age = 27.4 ± 8.9; start medication age NA) with ADHD, among them, 70.7% had prescribed ADHD medications | Mph | ASRS | Observational cross-sectional survey study exploring the role of positive and negative prescription stimulant-related expectancies in recreational and medical users of ADHD medication | Hierarchical cluster analysis identified two distinct groups among participants: medical users (72%) and recreational users (28%). Medical users were, on average, older and reported more frequent use of ADHD stimulant medication each month. Recreational users were more likely to report snorting their medication (34.09%) compared to medical users (7.08%). No significant differences were observed in the proportions of gender or ethnicity between the two groups | Positive expectancies, but not negative expectancies, predicted the frequency of use. Moreover, recreational users reported fewer positive and negative expectancies compared to medical users |

| Bejerot et al., 2010 [22] | Total sample of 133 individuals (71♂, 62♀; age NA; start medication age = 31.1 ± 10.9) with ADHD diagnosis and prescribed stimulant medications | Mph and Amph | DSM-IV | Observational longitudinal (2 years) study to explore factors linked to treatment persistence and to document side effects and reasons for discontinuation | Drug abuse was not detected in this cohort during the 2 years study | Medications tend to maintain their effectiveness over the long term for adult ADHD, with mild side effects. Stimulants can be considered safe in terms of potential misuse; however, this result should be interpreted considering that individuals with comorbid alcohol and drug abuse were excluded |

| McRae-Clark et al., 2011 [14] | Total sample of 14 individuals (6♂, 8♀; age = 33.9 ± 13.2; start medication age = NA) with history of stimulant misuse, abuse, or dependence treated with transdermal Mph | Transdermal Mph | DSM-IV | An 8-week, open-label trial evaluated the effectiveness of the Mph transdermal system | No misuse of study medication was observed during 8-week study | Mph transdermal system may be effective in improving ADHD symptoms in adults who have a history of misusing stimulant medications. It seems that the drug was not misused in this study; however, this result might be influenced by the relatively short duration of the investigation |

| Lensing et al., 2013 [23] | Total sample of 159 individuals (84♂, 75♀; age = 37.6 ± 11.1; start medication age NA) with ADHD diagnosis, among them 151 with prescribed ADHD medications | Mph and Amph | DSM-IV | Observational longitudinal (mean observation time was 4.5 years) study to explore the alignment between patient-reported and physician-reported treatment adherence and outcomes in adults with ADHD | In the cohort of individuals receiving ADHD treatment (N = 151), physicians indicated a manifestation of distrust regarding the usage of a dosage exceeding the prescribed amount in 8.6% of cases even though 82.1% of primary care physicians did not suspect misuse of prescribed medication. Within the subset of participants who discontinued pharmacotherapy for ADHD (N = 48), instances of misuse were reported as a causative factor in 14.6% of cases | The majority of primary care physicians did not harbor suspicions of stimulant medication misuse. A substantial consensus was observed between the physician’s lack of suspicion and patients’ reports of stimulant misuse, reaching a high agreement level of 91.7% |

| Ginsberg et al., 2015 [15] | Total sample of 25 prisoners (25♂, 0♀; age = 33.6 ± 10.8; start medication age = NA) with ADHD diagnosis and prescribed OROS- Mph | OROS-Mph | DSM-5 | Observational longitudinal (47 weeks) open-label study, as extension of a 52-week DB Plc-controlled trial, to asses’ long-term effects of ADHD pharmacotherapy. During the 99-week trial, prisoners were still in jail. Among trial completers, 25 were prospectively followed up clinically for 1 year (24/25, 96% participated fully or in part) and 3 years (20/25, 80% participation) after trial. At the 3-year follow-up, 75% (15 out of 20) of the respondents had been released from prison | No misuse of ADHD medication or side abuse of other drugs was detected by repeated, mandatory urine toxicology throughout the study period | Improvements in symptoms and functioning observed during a 52-week trial of OROS-Mph in long-term prisoners with ADHD and concurrent psychopathology, including substance misuse, appeared to endure up to 3 years after the trial’s conclusion (to 4 years of treatment in total). At the 3-year follow-up, most participants were employed and had not relapsed into criminal behavior or substance misuse, indicating the potential long-term benefits of the treatment |

| Youth sample | ||||||

| Gordon et al., 2004 [16] | Total sample of 162 adolescents in treatment for SUD (104♂, 58♀; age = 17.1 ± 1.4), among them 55 individuals (37♂, 18♀; age = NA; start medication age = NA) reported a lifetime diagnosis of ADHD (31 with current ADHD and 24 with past ADHD). 45.5% (n = 25) of the patients who reported a current diagnosis of ADHD had been treated with a psychostimulant medication prior to admission | Mph and Amph | Structured interview for ADHD | Observational cross-sectional study to explore prevalence and characteristics of adolescent patients with comorbid ADHD and SUD | Among the ADHD sample (n = 55), 41.8 % reported a lifetime psychostimulant abuse; the prevalence of abusers among individuals with current ADHD and prescribed psychostimulant medication (n = 25) is not available. Moreover, 20 % of the patients with co-morbid ADHD attested to illicit diversion of psychostimulant medication by sale, barter, or gift to others | Around 34% of adolescents in SUD treatment reported a lifetime ADHD diagnosis. Nearly one-third of the total sample acknowledged psychostimulant abuse, with those co-diagnosed with ADHD significantly more prone (p= 0.003) to report a history of psychostimulant abuse. For this susceptible SUD/ADHD group, treatment should prioritize nonstimulant medications with low abuse potential over easily abused and diverted psychostimulants |

| Molinaet al., 2021 [20] | Total sample of 341 individuals (252♂, 89♀; age = 15 ± 1.5; start medication age NA) with ADHD diagnosis and prescribed ADHD medications | Stimulant medication | DSM-V | Observational cross-sectional study, derived from pre-randomization baseline data from RCT of a stimulant diversion prevention workshop, characterizing the risk for stimulant diversion | The diversion rate was 1% among the total sample | While diversion was infrequent among adolescents treated in primary care settings, the risk seems to rise notably for older adolescents (p < 0.001). To enhance prevention effectiveness, it might be crucial to leverage existing psychosocial strengths and address stimulant-specific attitudes, behaviors, and social norms before the vulnerability to diversion escalates, especially in the later years of high school and into college |

| Mixed adult and youth sample | ||||||

| Bright et al., 2008 [18] | Total sample of 545 individuals (344♂, 201♀; age 12–17 yrs 20.7%, 18–25 yrs 35.6%, 26–34 yrs 18.0%, 35–39 yr 6.6%, ≥ 40 yrs 16.9%, 2.2% not reported; start medication age 6–12 yrs 20.4%; 13–17 yrs 23.3%, 18–24 yrs 17.2%, ≥ 25 yrs 26.8%, 12.3% not reported) which included 486 (89.2%) subjects with ADHD and prescribed ADHD medications | Mph and Amph | AARS | Observational cross-sectional survey study evaluating the misuse of prescription and illicit stimulants among individuals undergoing ADHD treatment | Approximately 14.3% of the total sample engaged in the abuse of prescription stimulants. Among those who abused, 67.9% used a single stimulant, 21.4% used 2 stimulants, 4.8% used 3 stimulants, and 6.0% used 4 or more stimulants. Short-acting agents were abused by 79.8%, long-acting stimulants by 17.2%, both by 2.0% and 1% other not specified formulation.. The most commonly abused stimulants were mixed amphetamine salts (40.0%), mixed amphetamine salts extended release (14.2%), and Mph (15.0%). Crushing pills for inhalation/snorting (75.0%) was the predominant method of abuse, followed by crushing and injecting (6.3%), microwaving/melting to snort (6.3%), and other methods (12.5%). Additionally, 16.5% of the total shared their prescription ADHD medications, with friends (67.0%) and relatives (28.4%) being the most common recipients | Individuals treated in an ADHD clinic face elevated risks of abusing prescription and illicit stimulants. The agents most frequently abused are those with characteristics conducive to a rapid high. This implies that long-acting stimulant preparations, designed for ADHD treatment, might have lower abuse potential compared to short-acting formulations |

| Bjerkeli et al., 2018 [24] | Total sample of 56,922 individuals (36,243♂, 20,679♀; age range 6–79; start medication age NA) with a Mph prescription, among them 44,244 individuals had ADHD diagnosis (gender NA; age NA; start medication age NA) | Mph | ICD-10 | Observational longitudinal (1 years) study to identify overuse of Mph and to investigate patterns of overuse in relation to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Data were obtained from Swedish national pharmacy dispensing data | 7.6% of the total sample were categorized as over-users (defined as having above 150% of the maximum recommended dose during 365 days from the first prescription fill). Among the ADHD group (44,244 individuals) the prevalence of over-users was 8.42% with 3.81% of them having above 200% of dosage needed | The prevalence of overuse appears to be associated with a previous diagnosis of alcohol and drug misuse, higher age, and prior use of ADHD medication, suggesting a potential link between exposure time and overuse |

| Guerra et al., 2022 [25] | Total sample of 25,603 individuals (19,772♂, 5831♀; age = 15.8 ± 11.9; start medication age NA) with a Mph prescription | Mph | Clinical | Observational longitudinal (13 years) study to assess the use of Mph and the extent of its abuse in the general population from 2005 to 2017 using a clustering classification method. Data were obtained from regional database Provence-alpes-côte d’Azur and Corsica health insurance | Over the 13 years under examination, the count of individuals receiving at least one dispensation of methylphenidate increased by 5.8 times. Within this group, the number of children rose by 5.2 times, whereas the count of adults surged tenfold. The clustering classification based on 4 quantitative active variables (number of prescribers, number of pharmacies, number of dispensing, quantity dispensed) calculated for each subject for the 9 months of follow-up for each year identified that 2.1% of the sample were “deviant users” and 97.9% were “no-deviant users”. Deviant group had older age, more frequent use of psychoactive drugs (benzodiazepine, morphine, opiate substitution treatment) and more Ritalin and less Concerta | Given the rise in individuals exhibiting “deviant” behavior, it is crucial to raise awareness within the medical community and among patients about the risk of methylphenidate abuse. The recent expansion of ADHD indications in adults and broader prescription conditions necessitate heightened vigilance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Callovini, T.; Janiri, D.; Segatori, D.; Mastroeni, G.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Di Nicola, M.; Sani, G. Examining the Myth of Prescribed Stimulant Misuse among Individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17081076

Callovini T, Janiri D, Segatori D, Mastroeni G, Kotzalidis GD, Di Nicola M, Sani G. Examining the Myth of Prescribed Stimulant Misuse among Individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2024; 17(8):1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17081076

Chicago/Turabian StyleCallovini, Tommaso, Delfina Janiri, Daniele Segatori, Giulia Mastroeni, Georgios D. Kotzalidis, Marco Di Nicola, and Gabriele Sani. 2024. "Examining the Myth of Prescribed Stimulant Misuse among Individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review" Pharmaceuticals 17, no. 8: 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17081076

APA StyleCallovini, T., Janiri, D., Segatori, D., Mastroeni, G., Kotzalidis, G. D., Di Nicola, M., & Sani, G. (2024). Examining the Myth of Prescribed Stimulant Misuse among Individuals with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals, 17(8), 1076. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17081076