Abstract

Background/Objectives: Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions and significantly contributes to local and global disease burden. Common pharmaceuticals that are used to treat OA cause significant side effects, thus non-pharmaceutical bioactive alternatives have been developed that can impact OA symptoms without severe side-effects. One such alternative is the Red Algae Lithothamnion species (Litho). However, there is little mechanistic knowledge of its potential to effect OA gene expression, and a human in vitro model using commercially available cell lines to test its effectiveness has yet to be developed. Methods: Human osteoblast (hFOB 1.19. CRL-11372) and chondrocyte (C28/I2) cell lines were co-cultured indirectly using transwells. IL1-β was used to induce an inflammatory state and gene expression profiles following treatment were the primary outcome. Conclusions: Results indicated that the model was physiologically relevant, remained viable over at least seven days, untreated or following induction of an inflammatory state while maintaining hFOB 1.19. and C28/I2 cell phenotypic characteristics. Following treatment, Litho reduced the expression of inflammatory and pain associated genes, most notably IL-1β, IL-6, PTGS2 (COX-2) and C1qTNF2 (CTRP2). Confirmatory analysis with droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) revealed that Il-1β induced a significant reduction in C1qTNF2 at 7 days which was ameliorated with Litho treatment. These data present a novel and replicable co-culture model of inflammatory OA that can be used to investigate bioactive nutraceuticals. For the first time, this model demonstrated a reduction in C1qTNF2 expression that was mitigated by Red Algae Lithothamnion species.

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions globally and contributes significantly to disease burden [1,2]. It is estimated that OA effects 595 million individuals worldwide [3,4,5] and ~13% of those over 50 years [6]. OA is a degenerative disease caused by the failure of normal biological processes to repair damaged tissue leading to abnormalities in synovial joints [7], such as subchondral osteophytes [8], local inflammation or synovitis [9,10,11,12], bone marrow lesions [13] and systemic low-grade inflimation [14]. It is well established that inflammatory processes are key drivers of OA, often exacerbated by immune system activation particularly in older populations, but not exclusively [15,16].

There is no known cure for OA [17,18,19,20,21], however drug therapy, physical therapy and surgery are common treatments [22]. In the early stages, pain relief and inflammatory reduction can be achieved through appropriate exercise and weight loss strategies. However, adherence is often challenging [23] and these methods are commonly accompanied by oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other analgesics [24,25]. Current global data shows that four in every ten OA patients seeking healthcare are prescribed some form of NSAID [26], which is not surprising as it is currently a “strongly recommended” strategy for OA clinical management [27,28]. Further, OA patients frequently use Paracetamol or acetaminophen, N-acetyl-p-aminophenol [29] (34%; in isolation or in combination with NSAIDs) and opioids (8–26%), the volume of which has been described as “alarmingly high” and shown to be inappropriately dispensed [30].

All these common pharmaceuticals can cause significant side effects. While some NSAIDs are effective at improving pain symptoms and physical function, their regular use can result in gastrointestinal complications, renal disturbances and severe cardiovascular events [31]. Paracetamol may be ineffective for treating some types of OA pain [32,33], but it has similar side effects as ibuprofen [34], particularly when consumed at higher doses [35], and its overuse can cause liver injury, hepatotoxicity, mitochondrial toxicity [36,37]. The negative health effects of opioid use are well documented, but they are frequently prescribed for OA and usage is expected to triple in the coming years [30,38]. Critically, a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that the tolerability of opioids is low, efficacy for pain relief in OA is not clinically relevant and the potential risks of harm are high [39,40,41]. Therefore, non-pharmaceutical bioactive alternatives, that can reduce pain but without the severe side-effects, could be effective early interventions and can be used in isolation or alongside pharmaceuticals [24,42,43,44] to improve OA symptoms [45,46,47,48]. However, to date there is no readily accessible physiologically relevant in vitro model to test their potential molecular impact (morphology, inflammation etc.) or safety [49,50]. There is a need to develop such a model using human cell lines that addresses some current methodological limitations and to reduce the burden of animal testing [50], particularly in OA [49].

One non-pharmaceutical bioactive alternatives, Red Algae Lithothamnion species have been reported, individually and in combination with other bioactives, to improve OA symptoms and functional performance in vivo [51,52,53,54]. Two double-blinded randomised trials utilising Lithothamnion species [53,54] showed improved moderate-to-severe knee OA pain, symptoms (stiffness) and functional performance (6 m walking distance) compared to Glucosamine [54], and when NSAIDs were reduced by ~50% Lithothamnion treatment improved physical performance [53]. Early mechanistic work suggested this may be a result of inhibited NFκB pathway, reduce tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and COX-2, along with reduced serum TNF-α [52,54,55,56]. However, it remains unclear to what extent Lithothamnion can mediate the inflammatory response of OA in a human physiologically relevant in vitro model and what pathways are of particular importance.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to develop an accessible, cost effective, novel in vitro human co-culture model, intended for nutraceutical investigation and to assess the effect of Lithothamnion species on the inflammatory response to an OA environment.

2. Results

2.1. Development of Co-Culture Model

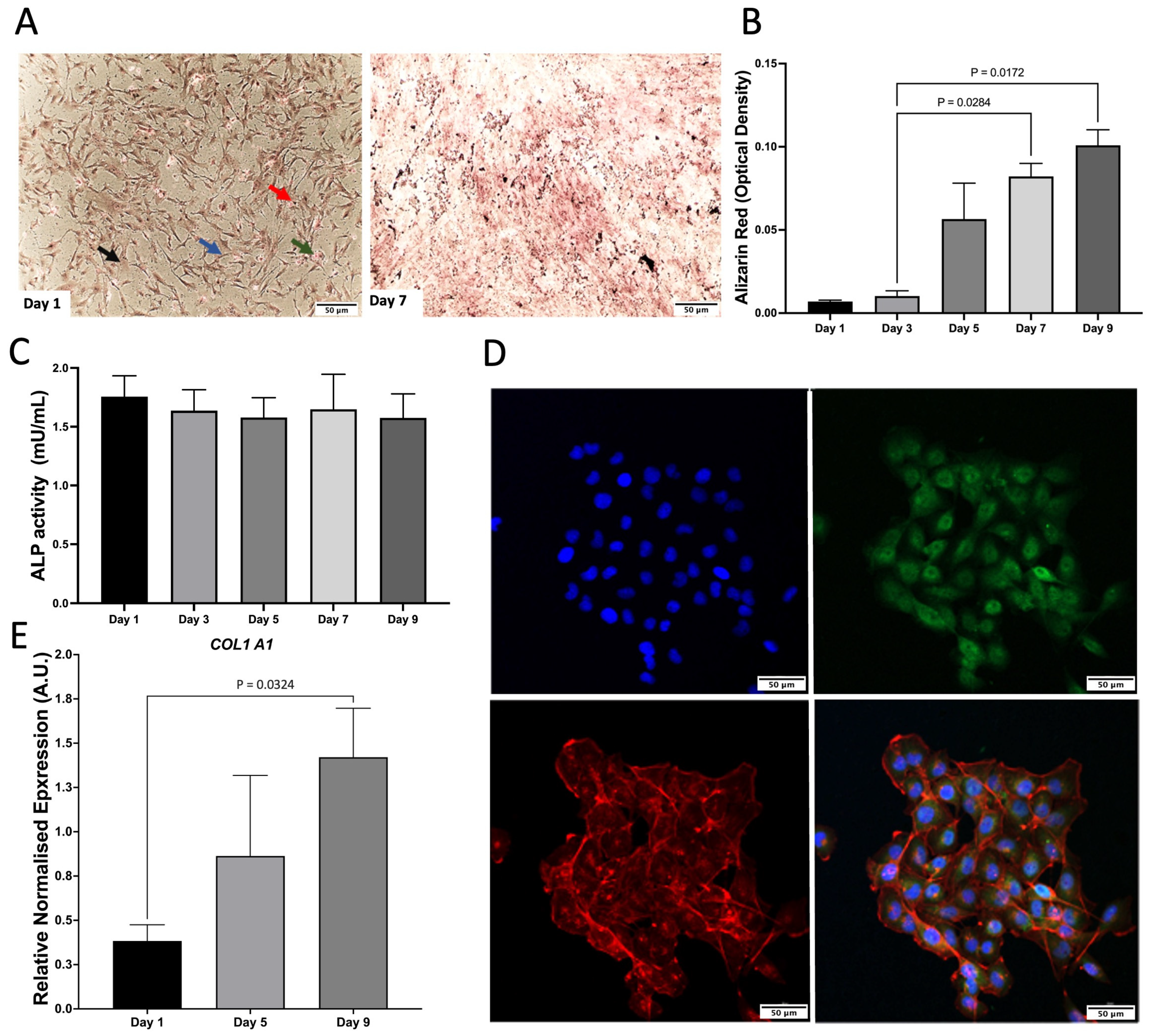

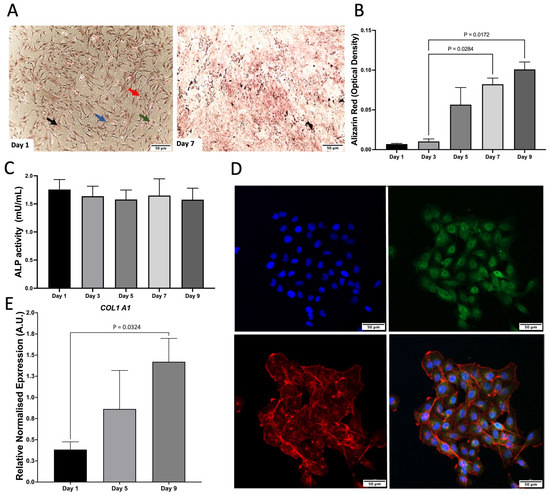

As a monoculture, hFOB 1.19. cells were characterised by Von Kossa staining, Alizarin Red (ARZ) and Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. There was an increase in mineralisation and ALP activity, which remained consistent across time (Figure 1A–C). C28/I2 cells were characterised by relative gene expression of COL1A1, which increased across time and the presence of aggrecan staining was shown via confocal microscopy (Figure 1D,E).

Figure 1.

Characterisation of monocultures. (A) Von Kossa staining of hFOB 1.19. on day 1 and 7. Red arrow, calcium mass deposits stained black. Blue arrow, calcium dispensed deposits stained grey; Green arrow, nuclei stained red; Black arrow, cytoplasm stained light pink. (B) Alizarin Red (ARZ) quantification showing osteoblast cell calcium/mineral deposition across days 1–9 of cell growth, n = 3 with assays performed in triplicate. The data is presented as the mean ± SEM. (C) Alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP) for hFOB 1.19, n = 3 with assays performed in triplicate (p = 0.972). The data is presented as the mean ± SEM. (D) Confocal microscopy images of aggrecan (day 1). Cells were stained with aggrecan (green), nuclear stain dapi (blue), and phalloidin to stain f-actin (red). Scale bar: 50 μm. Images are representative of 3 biological replicates. (E) COL1A1 gene expression of C28/I2 compared to day 1. This data represents n = 3 biological replicates.

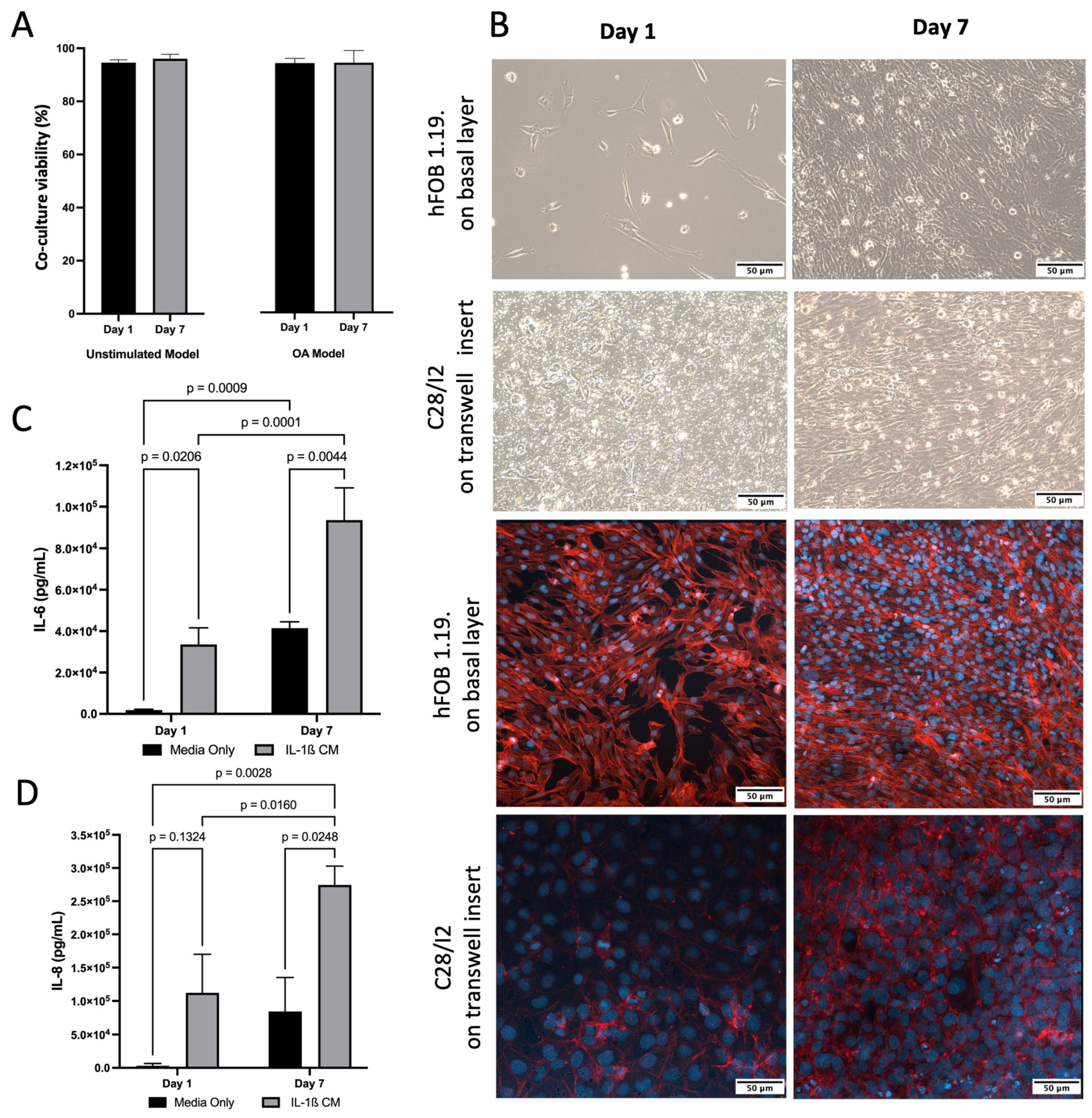

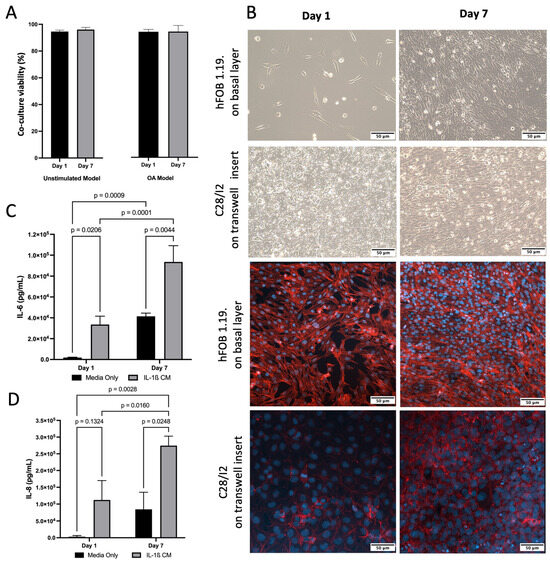

For co-culture, both hFOB 1.19. and C28/I2 cells demonstrated typical growth patterns for each cell type and morphology was consistent with healthy cells. This was also confirmed by presto blue viability data across 7 days (Figure 2A). Light and confocal Microscopy confirmed that hFOB 1.19. growth and C28/I2 cells maintained their location on the transwell inserts and typical growth characteristics (Figure 2B). Cell viability remained high (>95%) for co-culture (C28/I2 and hFOB 1.19. cells) and cell size consistent (~16.5 μm) across time. To induce inflammation, thus simulating an osteoarthritic-like scenario (OA model) [57], IL-1β was added to the co-culture at 10 ng/mL, viability (>93%) and cell size remained (~16.5 μm) consistent with no significant drop in viability over 7 days (Figure 2A). The presence of inflammation was confirmed by IL-6 and IL-8 ELISAs, markers known to be present and often used in OA experimental designs [14,57]. There was a significant increase in IL-6 between day 1 and day 7. In the presence of IL-1β, IL-8 increased by 3.6 and 3.3 fold for day 1 and day 7 respectively and IL-6 increased by 17.7 and 2.3 fold for day 1 and day 7 respectively, compare to untreated media condition (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Characterisation of inflamed co-culture model. (A) Co-culture cell viability and cell size across time following induction of inflammatory state via IL-1β CM (OA Model, p > 0.05) or media only (Unstimulated Model, p > 0.05). (B) (Top) Inverted light microscopy images of hFOB 1.19 cells seeded at 1 × 104 in media only on the basal layer at day 1 and day 7. C28/I2 cells seeded at 1 × 104 on transwell inserts in media only day 1 and day 7. (Bottom) Confocal Microscopy images stained for f-actin (red—phalloidin) and nucleus (blue—dapi) showing that cells grew on the transwell and did not traverse the membrane (C28/I2), and hFOB 1.19 cells on basal layer. Images scaled at 50 μm, and representative of three biological replicates. (C) Elevated concentrations of IL-6 following induction of inflammatory state via IL-1β CM, compared to media only on day 1 and day 7. Mean data of three biological replicates, analysed in triplicate (n = 9) are presented ± SEM. (D) Elevated concentrations of IL-8 following induction of inflammatory state via IL-1β CM, compared to media only on day 1 and day 7. Mean data of three biological replicates, analysed in triplicate (n = 9) are presented ± SEM.

2.2. Effect of Treatment on Co-Culture Phenotype

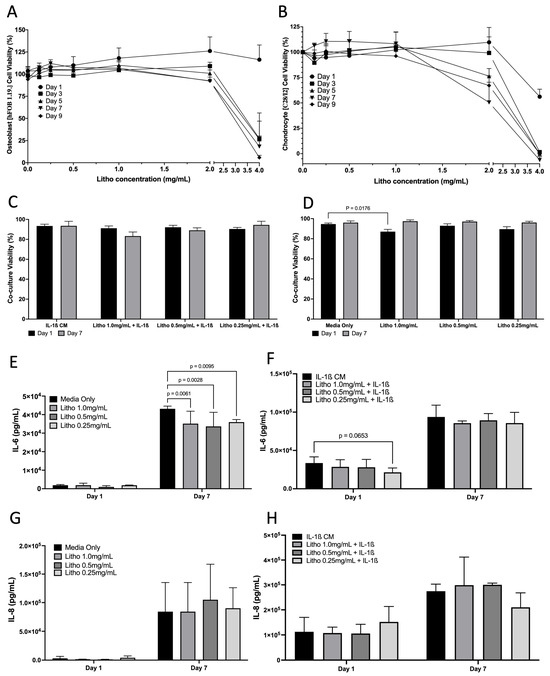

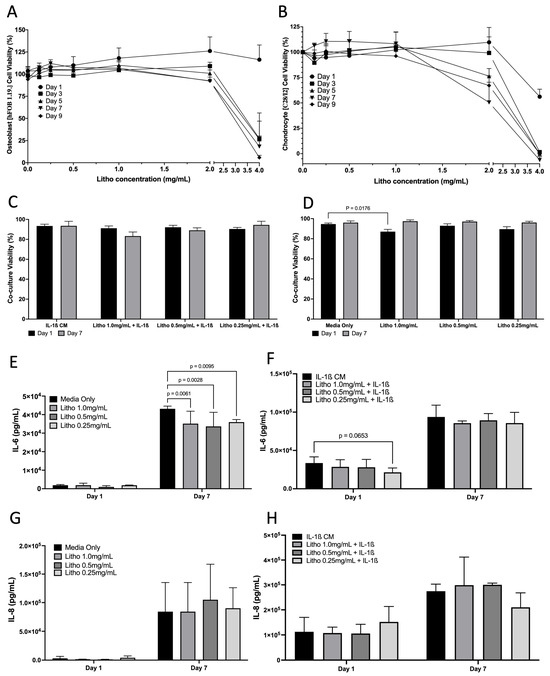

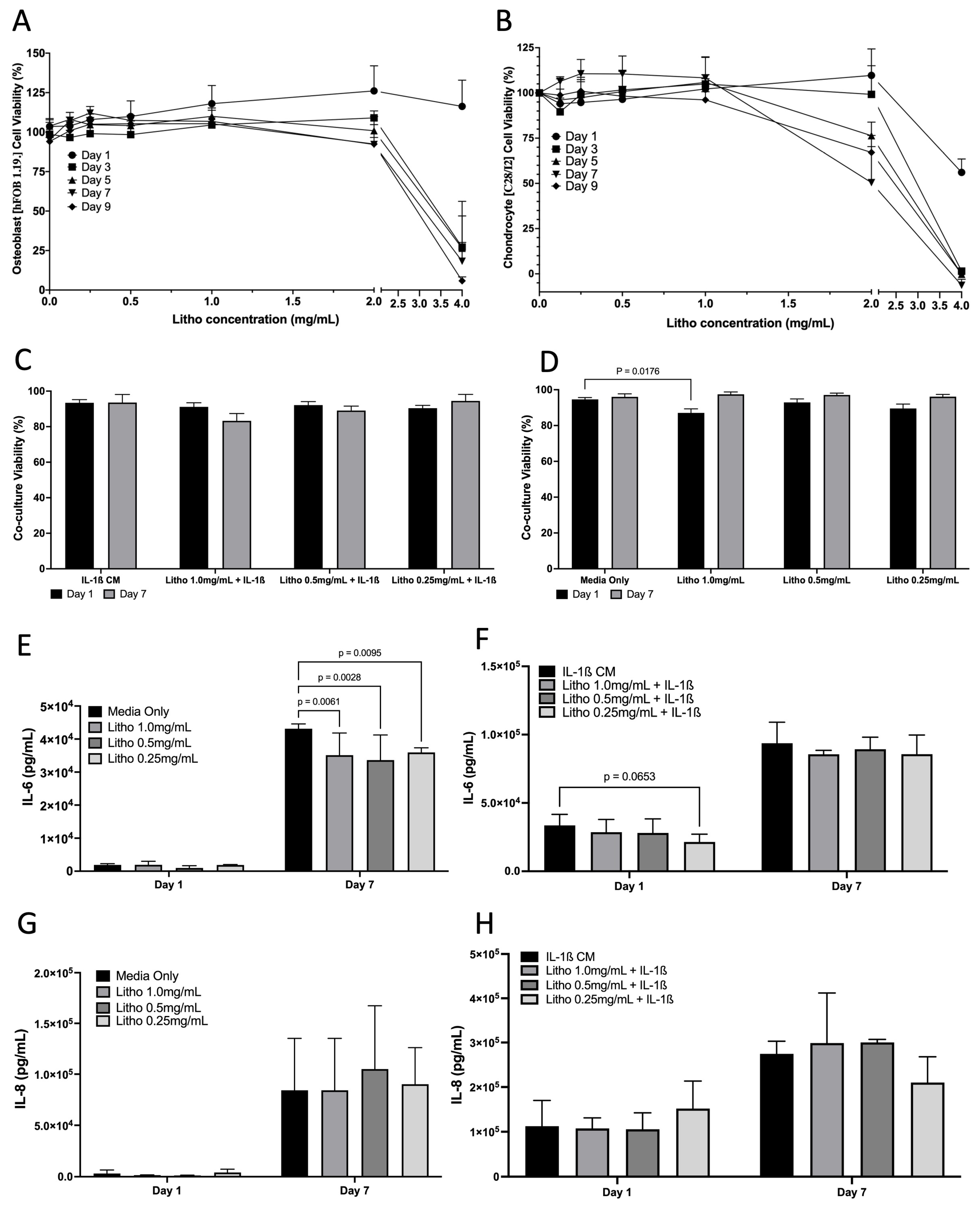

Cell viability assay demonstrated that Litho had no impact on cell viability until beyond 2 mg/mL for hFOB 1.19 cells and up to 1 mg/mL for C28/I2 cells across the experimental period when grown as monocultures (Figure 3A,B). In co-cultures, there was no difference in cell viability when treated with IL-1β CM, or IL-1β combined with Litho. There was a small drop in viability for cells treated with Litho 1.0 mg/mL (87%), however this recovered over the course of the 7 days (97%) (Figure 3C,D). Litho at all doses significantly reduces IL-6 (p < 0.006) compared to untreated controls at day 7, but not with added IL-1β CM, although there was a tendency for the 0.25 mg/mL dose to be lower than IL-1β media (p = 0.07; Figure 3E–H). There was no effect of treatment dose on IL-8, with or without IL-1β CM.

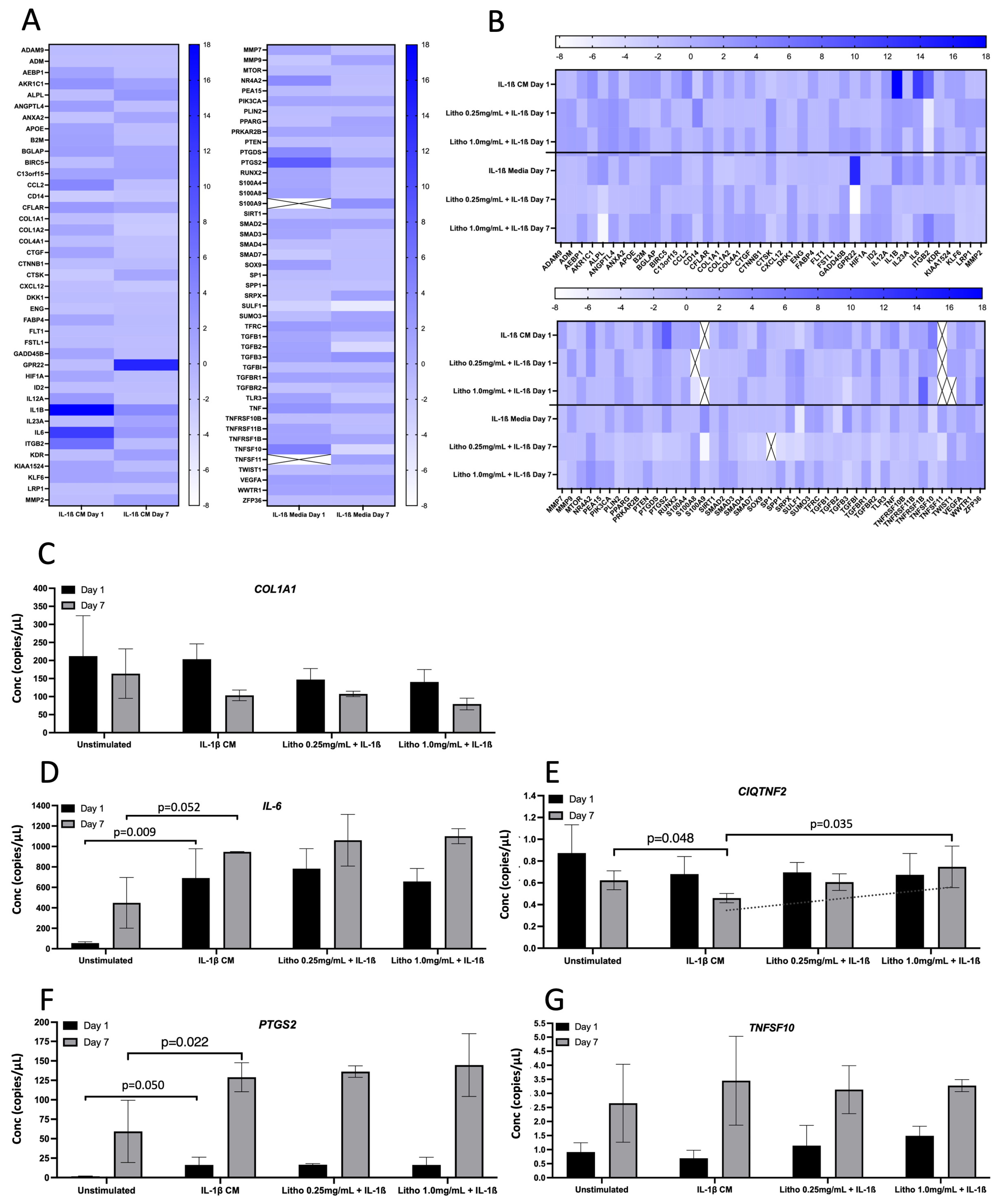

2.3. Impact of Treatment Co Culture Gene Expression

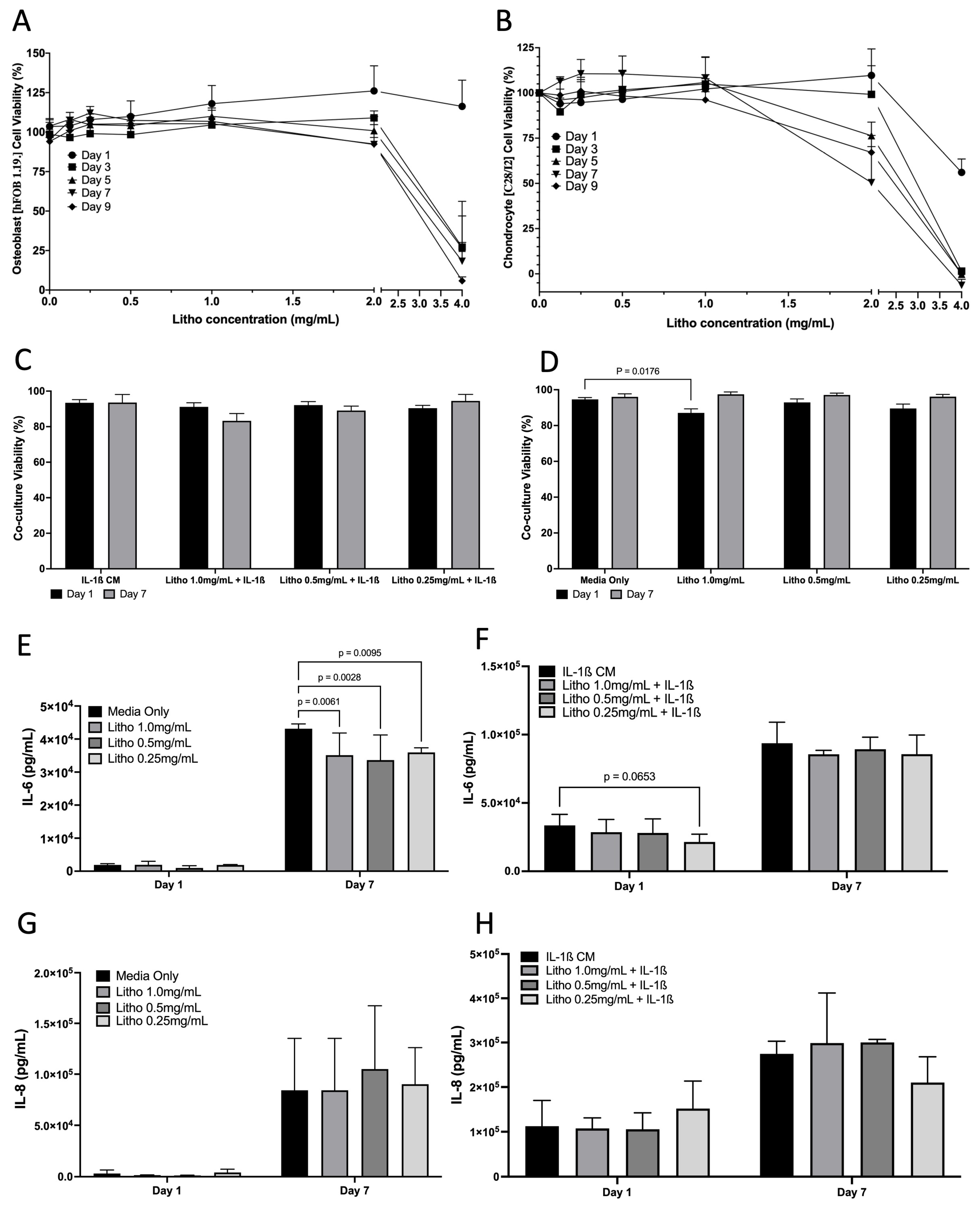

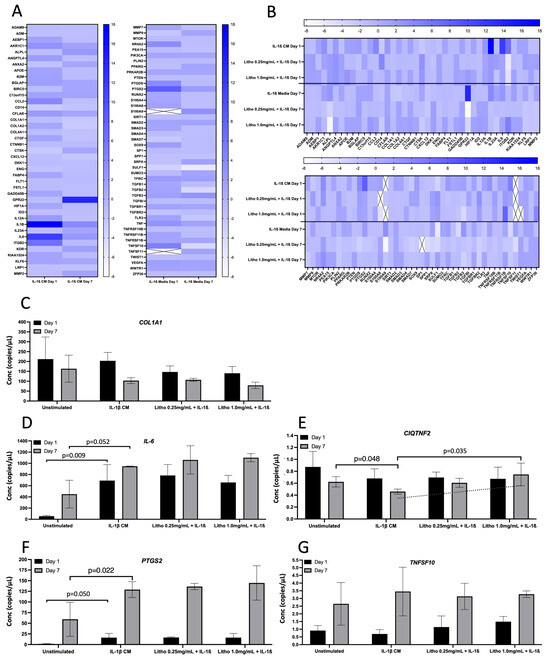

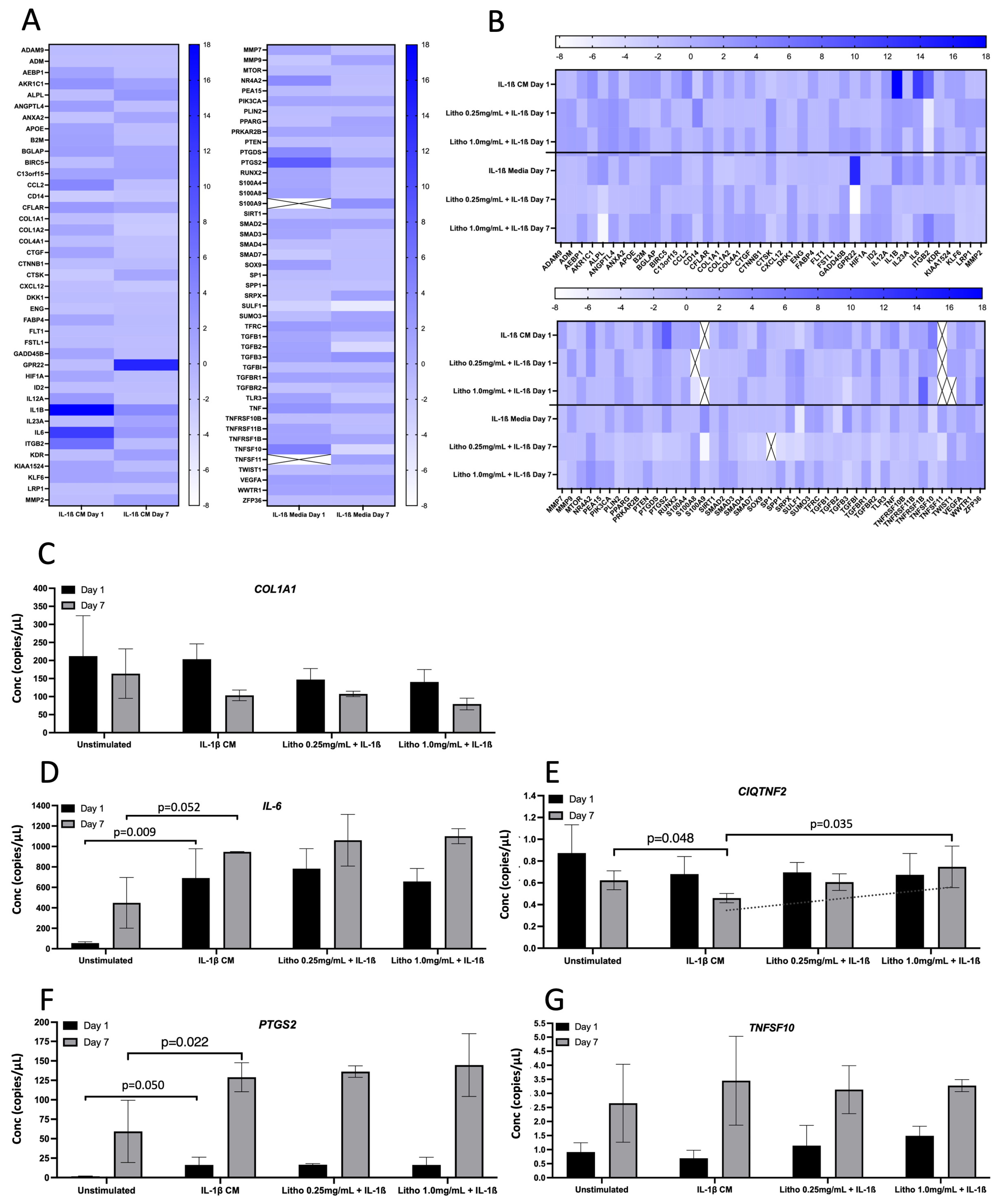

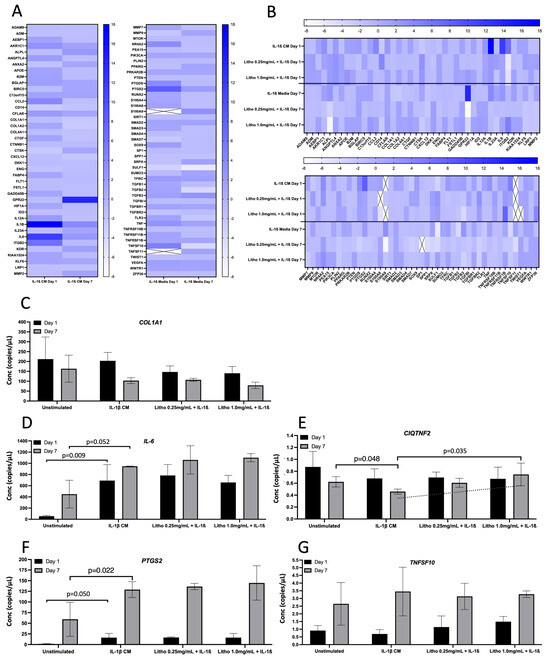

For co-culture with IL-1β CM, IL-1β showed the greatest change in normalised expression, with an 18.0 fold increase, reducing to 3.84 fold following 7 days of repeated dosing. IL-6 expression increased 11.86 fold at day 1 and reduced to 2.50 fold after 7 days. ITGB2 increased by 6.54 fold, reducing to −1.02 after 7 days. PTGS2 was upregulated by 8.37 fold compared to untreated control (IL-1β CM), reducing to 2.0 fold after 7 days. Interestingly, GPR22 was downregulated, albeit not biologically relevant at day 1 (−1.17 fold), but substantially upregulated at day 7 (14.20 fold; Figure 4A). Following treatment with experimental material, Litho reduced the expression of IL-1β by ~16 fold, IL-6 by ~10 fold, PTGS2 by ~7 fold and ITGB2 went from being upregulated (6.54 fold) to downregulated (~−6.0 fold) for both doses at day 1. Following 7 days of repeated dosing, GPR22 went from being upregulated (14.20 fold) to downregulated (−3.94 fold) in both doses (Figure 4B).

Seven genes were selected for confirmatory analysis by ddPCR following pathways of interest that were derived from qPCR array data (pain and inflammation). Data from three genes (CCL2, TGFβ3 and PTGDS) were below detectible limits, thus were not statistically analysed or presented. Of the remaining genes (Figure 4C), there was no statistical difference observed for COL1A1 or TNFSF10, however at day 7, the addition of IL-1β appeared to reduce the expression of COL1A1 (p = 0.15), which was unaffected by Litho (p < 0.50). The introduction of IL-1β CM increased IL-6 and PTGS2 expression on day 1 and 7 (p = 0.003 and p = 0.034; p = 0.032 and p = 0.022, respectively) but again were unaffected by Litho treatment (p < 0.39). PTGS2 expression was significantly affected by time in each experimental condition (greater expression on day 7; p > 0.006). IL-1β induced a significant reduction in C1QTNF2 compared to unstimulated control at day 7 (p = 0.048), however this reduction was returned to untreated levels by Litho 1.0 mg/mL, which was significantly different from IL-1β CM (p = 0.022). CIQTNF2 expression trended towards an increased dose response in expression but did not reach the a priori alpha (p for trend = 0.061, R2 = 0.537). There was no effect of IL-1β or Litho on CIQTNF2 at day 1.

Figure 3.

Effects of Litho on monoculture and co-cultures. Dose response curves for in Osteoblasts (A) and Chondrocytes (B) (no IL-1β CM) (no statistical analysis performed). (C) Co-culture cell viability across time in the OA model following treatment. (D) Co-culture cell viability across time in the unstimulated model (no IL-1β CM) following treatment. (E) IL-6 of unstimulated model following treatment. (F) IL-6 of OA model following treatment. (G) IL-8 of unstimulated model following treatment. (H) IL-8 of OA model following treatment. All experiments are calculated as mean data of three biological replicates, analysed in triplicate (n = 9) are presented ± SEM.

Figure 3.

Effects of Litho on monoculture and co-cultures. Dose response curves for in Osteoblasts (A) and Chondrocytes (B) (no IL-1β CM) (no statistical analysis performed). (C) Co-culture cell viability across time in the OA model following treatment. (D) Co-culture cell viability across time in the unstimulated model (no IL-1β CM) following treatment. (E) IL-6 of unstimulated model following treatment. (F) IL-6 of OA model following treatment. (G) IL-8 of unstimulated model following treatment. (H) IL-8 of OA model following treatment. All experiments are calculated as mean data of three biological replicates, analysed in triplicate (n = 9) are presented ± SEM.

Figure 4.

Gene expression for the OA model. Gene expression following exposure to IL-1β CM and subsequent treatment with Litho at 0.25 mg/mL and 1.0 mg/mL. (A) Heat map showing relative gene expression normalised to media only across time. (B) Heat map showing relative gene expression following treatment. Samples were normalised to OA model (IL1-β CM). Heat map colour intensity represents fold change in gene expression. Cells with an “X” represent genes that were not expressed sufficiently for detection. (C) ddPCR gene expression for selected confirmatory analysis following arrays for COL1A1; (D) IL-6; (E) CIQTNF2. The dashed line represents p for Trend (p = 0.061); (F) PTGS2; (G) TNFS10. Data presented in copies/µL.

Figure 4.

Gene expression for the OA model. Gene expression following exposure to IL-1β CM and subsequent treatment with Litho at 0.25 mg/mL and 1.0 mg/mL. (A) Heat map showing relative gene expression normalised to media only across time. (B) Heat map showing relative gene expression following treatment. Samples were normalised to OA model (IL1-β CM). Heat map colour intensity represents fold change in gene expression. Cells with an “X” represent genes that were not expressed sufficiently for detection. (C) ddPCR gene expression for selected confirmatory analysis following arrays for COL1A1; (D) IL-6; (E) CIQTNF2. The dashed line represents p for Trend (p = 0.061); (F) PTGS2; (G) TNFS10. Data presented in copies/µL.

3. Discussion

To date, in vitro co-culture models of OA have mostly focused on cartilage only, often with animal tissues/cells as proxies for human disease and have not considered bone cell stimuli or cell line crosstalk [49,58,59]. Building on previous methods [60,61], the present study developed a readily accessible physiologically relevant human in vitro pro-inflammatory co-culture model representing OA (stimulated by IL-1β [57,58]). The co-culture model utilised cell lines that require the same media environment, was effective across at least seven days and was designed for ease of use while maintaining hFOB 1.19. and C28/I2 cell phenotypic characteristics. In addition to providing evidence of general OA inflammatory status from IL-1β stimulation [57], the present data showed confirmed gene expression of well know OA pain and inflammatory markers IL-6 [62] and PTGS2 [63,64]. This suggests that the present 2D human cell line co-culture model can be used as a reproducible tool to investigate both inflammation and molecular pain phenotypes in OA.

By combining these two cell lines, the model mimics, to some degree, the native in vivo OA condition by considering osteochondral crosstalk [59]. For example, stimulation with IL-1β can decrease viability in C28/I2 cells [65] and increase viability in hFOB 1.19. [66], thus the present model neutralized these individual physiological responses resulting in stable pooled viability and a more native OA environment. This likely occurred because as IL-1β induced apoptosis in C28/I2, it simultaneously increased the transcriptional activity of Activator Protein-1, thus modulating the impact of IL-1β on cell death in both cell lines [65,67,68]. Further, the present data showed increased levels of COL1A1 over time which can be an indicator of dedifferentiation in chondrocytes, a common occurrence for immortalised and primary chondrocytes grown in vitro [69,70]. However, chondrocytes can acquire many degenerated phenotypes at the onset of OA, including a “dedifferentiated-like” phenotype that may contribute to OA progression [71]. Therefore further enhancing the physiological relevance of the model. A number of chondrocyte cell lines have been generated in an effort to overcome the dedifferentiation process however none are derived from articular cartilage making them less suitable for OA investigations. More importantly, they have been shown to be less sensitive to inflammatory stimuli [70], which is of particular importance in OA studies including the present one.

To investigate the effectiveness of the model for assessing OA related molecular mechanisms, the present study used a bioactive nutraceutical that has previously been shown to improved OA symptoms in vivo (Litho). As such, the RNA arrays revealed that Litho reduced the expression of key inflammatory genes, most notably IL-1β and IL-6. While these expressions were not confirmed by ddPCR, Litho did reduced extracellular IL-6 prior to treatment with IL-1β and tended towards a reduction in day 1 following IL-1β stimulation. It is possible that Litho could be affecting the inflammatory mediators at the protein level and less so at the gene expression level, but this is yet to be experimentally tested. Further, the likely mechanism for suppressed inflammatory markers in the non-stimulated condition was though the NF-κB transcriptional activity, which was reduced following exposure to Lithothamnion species in macrophages with lipopolysaccharide [56]. This action may have resonated, in part, from the mineral structure of Lithothamnion as a number of individual minerals present in Litho have been shown to negatively regulate NF-κB [72]. For example, Mg can down regulate inflammatory genes (IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10) and decrease NF-κB nuclear translocation and phosphorylation [73] The IL-1β stimulus used in the present study may have overpowered some of the inflammatory mediating capacity of Litho as in vivo studies utilising Lithothamnion species have shown a significant effect in mild-moderate disease, rather than severe OA [51,53,54]. Nonetheless, these findings agree somewhat with previous studies investigating Lithothamnion [55,56,74] and confirm that this species of Algae has anti-inflammatory properties, as evident in the present model, that warrant further mechanistic investigation. Some larger error were present in individual outcome measures; however these were not completely unexpected given the use of multiple cell lines, inflammatory stimulus and treatment with an organic material. Nonetheless, additional caution is required when interpreting these data.

Litho also reduced the expression of Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2; also named COX-2) by ~7 fold on day 1 and maintained this reduction of >2 fold on day 7. Reduced expression of this gene signifies a potential capacity to improve the disease state as PTGS2 can promote inflammation and oxidative stress, while inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress-related substances increase its expression [75,76,77]. This finding is further supported by an LPS stimulated murine macrophage model that was acutely treated with Lithothamnion (0.5 mg/mL) and reduce COX-2 relative expression over a 6-h period [56]. As IL-1β induces COX-2 (PTGS2 in the present findings) in OA specific tissues [78], this is further supported by the present finding that Litho reduced the expression of IL-1β by ~16 fold and other data showing that Lithothamnion species can reduce extracellular IL-1β by ~2 fold, again in macrophages [55]. Given the nature of these markers as pain therapy targets it is possible that the mineral composition of Litho and potential delivery mechanism [79] could provide a possible mechanistic indication. As above, Mg (the second most abundant mineral present in Litho) has a growing body of evidence for its potential therapeutic role in OA [80] and has the capacity the inhibit the expression and enzymatic activity of COX-2 [81]. This is supported in vivo, where the use of Lithothamnion species as part of a nutraceutical combination reduced the use of analgesics by ~70% during a 12 week intervention [51]. However, the precise mechanisms are yet to be elucidated.

A novel finding of the current study is that of the C1QTNF2 gene. Also known as C1q/TNF-related protein (CTRP [2]), C1QTNF2 is a member of a highly conserved family of proteins known mostly for their role in metabolism and as adipokines, but also for their anti-inflammatory properties [82,83]. CTRPs are paralogs of adiponectin which is a well-known adipokine that possess anti-inflammatory capacity, of which CTRP2 mostly resembles the amino acid composition [84]. Specifically, CTRP2 expression has been shown to reduce oxidative stress, inhibit cytokine production such as TNF-α and IL-6 and has been linked to a number of inflammatory associated disease states (e.g., Coronary Artery Disease) [85]. In agreement with these roles, the present findings showed that following seven days of inflammatory exposure with IL-1β C1QTNF2 expression was reduced and with the addition of Litho, C1QTNF2 expression returned to untreated levels, in a dose dependent manor. These data demonstrated, for the first time, that C1QTNF2 gene expression may have a role in OA disease state and that it may be reversed by a bioactive nutraceutical.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Maintenance

Immortalised human foetal osteoblastic (hFOB 1.19. CRL-11372, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) Manassas, VA, USA) and human immortalised Chondrocyte (C28/I2; Merck, Dorset, UK) cell lines were cultured in phenol-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (GIBCO, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 1% penicillin, streptomycin and 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Paisley, UK). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The medium was changed every three days under aseptic conditions. Passaging of confluent monolayers were carried out at 80–90% using accutase solution (Merck, UK). C28/I2 cells were discarded after passage 10 to ensure that no abnormal morphological changes occurred, as per certificate of analysis (Merck, UK).

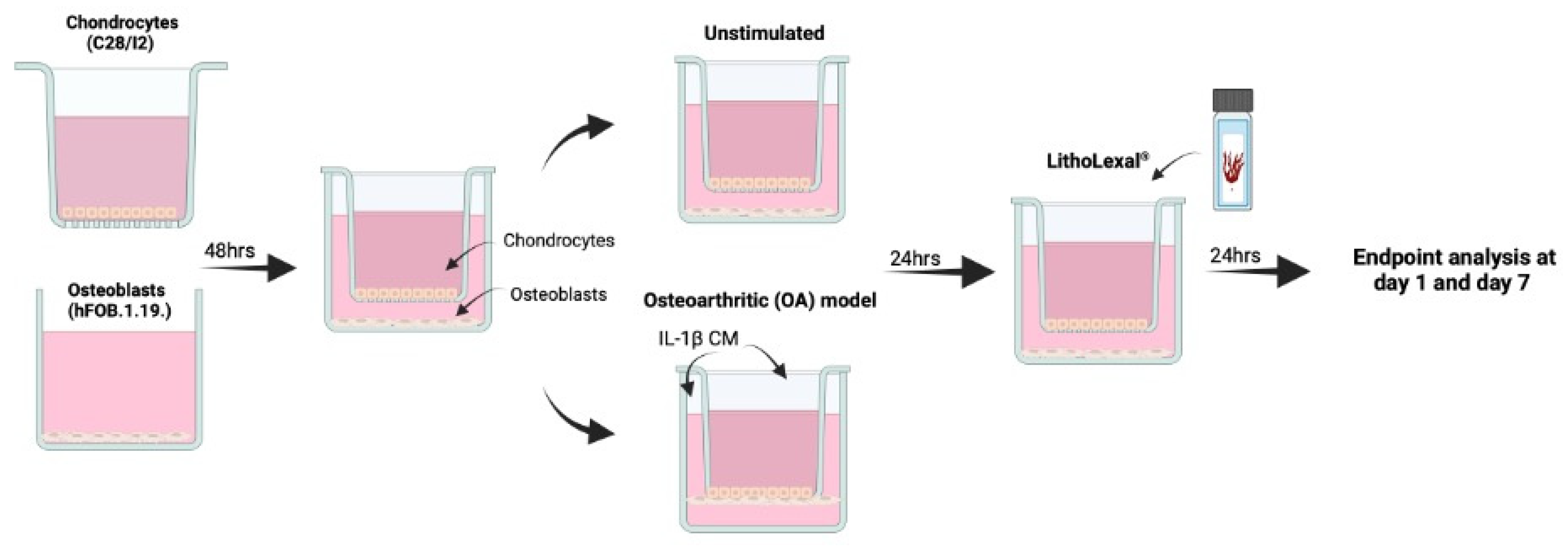

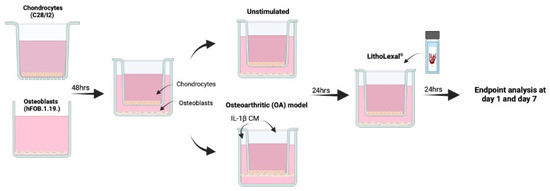

Cells were co-cultured indirectly using transwell inserts as previously described (Figure 5) [60]. C28/I2 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/mL onto the apical side of FalconTM cell culture inserts (transparent PET membrane with 3 µm pores; Fisher Scientific, Cambridge, UK, 12- or 6-well size). hFOB 1.19. cells were seeded at 1 × 104 into basal compartment to later form the basal layer of the indirect co-culture. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48 h. To induce an osteoarthritic inflammatory disease-state an indirect co-culture model was used, which enabled the assessment of cell-cell interaction (of the two cell types) and the effect of the co-culture on growth and behaviour of both cell types. Media from both the basal layer and transwell were aspirated and replaced with IL-1β (Merck, UK) conditioned media (CM), a known OA stimulant [57,58], at 10 ng/mL (total volume = 4.5 mL per co-culture well) and incubated in the same conditions for a further 24 h. For both the apical and basal layer separately, IL-1β CM was discarded and replaced with experimental material (see below) in IL-1β CM or media only as a control. Inserts were then transferred into the appropriate basal compartment, containing experimental material plus IL-1β media (or media only as control) and hFOB 1.19 cells. Cells were harvested after 24 h of treatment (day 1). The remaining cells underwent a media change with fresh experimental media plus IL-1β (or media only) every two days and harvested at day 7. During each harvest, supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 230× g for 5 min and stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Figure 5.

Schematic of co-culture OA model. hFOB 1.19 and C28/I2 cells were co-cultured indirectly using transwell inserts. C28/I2 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/mL onto the apical side of cell culture inserts and hFOB 1.19. cells were seeded at 1 × 104 into basal compartment of the transwell system. Both cell lines were left for 48 h to adhere after which the transwell insert containing C28/I2 cells was added into the basal compartment, with hFOB 1.19. cells seeded on the base. To induce an OA inflammatory-like state, media was aspirated and replaced with IL-1β conditioned media (CM) at 10 ng/mL for 24 h prior to treatment. Created in BioRender. IVTG, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/j70y844 (last accessed on 9 February 2025).

4.2. Experimental Material

The Algae material was harvested from the calcareous cytoskeleton of Lithothamnion species, a member of the Corallinacea family. By utilising proprietary extraction technology (Nordic Medical Ltd., London, UK), its multimolecular complex was preserved retaining a unique porous microstructure [79,86] (referred to herein as Litho).

Lithothamnion species are rich in calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg) and a variety of trace elements that are absorbed from sea-water during the organism’s life [51,87]. The application used in this experiment was recognised as safe for human consumption by the Food and Drug Administration FDA (GRAS 000028). The Red Algae extract contained ~12% Ca, ~1% Mg and measurable levels of 72 other trace minerals [74] (batch confirmed by chemical analysis, Marigot Ltd. Co Cork, Carrigaline, Ireland) and is commercially available in the UK as LithoLexal® (London, UK). The experimental solution was prepared by re-suspending in phenol-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C for 30 min, then filter sterilised using a 0.22 µM filter. Both individual and co-culture models were treated with a range of doses 0.25–1.0 mg/mL [55,56] for either 24 h or seven days.

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

At the appropriate time points, media was removed from each well and replaced with 10% solution of Presto Blue cell viability reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cambridge, UK), as per manufactures instructions. All samples were run in triplicate, per biological replicate (n = 3). Fluorescence was measured with an automated microplate fluorometer (FLUOstar Omega, BMG LabTech, Aylesbury, Shropshire, UK) using an excitation wavelength of 544 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm. Cell viability was calculated as a percentage of the untreated negative control, with H2O2 1 mM as the positive control.

4.4. Immunofluorescence

C28/I2 were stained with chondrocyte marker Aggrecan. Transwell inserts were washed (0.1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS) and fixed (4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to the apical and basal sides) at room temperature (RT) for 15 min. Inserts were washed, permeabilised (0.1% v/v Triton X-100 for 20 min), and washed twice before being blocked using 1% w/v BSA for 1 h at RT. Cells were stained with Aggrecan monoclonal primary antibody (1:200) (Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK) for 3 h at 4 °C. Before incubating with secondary antibody, Goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluro 488 (Ex 490 nm/Em 525 nm) (1:500) (Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK) and Phalloidin Alexa Fluor 594 (Ex 590 nm/Em 618 nm) staining F-actin (1:400) (Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK) for 1 h at RT. Inserts were then mounted with Vectashield mounting medium Dapi (Ex 360 nm/Em 460 nm) (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) and imaged Zeiss LSM980 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

4.5. Von Kossa Staining

hFOB 1.19. cells were assayed with Von Kossa (150687, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) to identify calcium specific deposition as per manufactures instructions. Briefly, cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min at RT. Cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated in silver nitrate solution (5%) for 30–60 min under ultraviolet light (Analytik Jena UV Lamp, Fisher Scientific, Cambridge, UK), then washed again. Unreacted silver nitrate was removed by adding 5% sodium thiosulfate for 5 min. Nuclear factor red staining solution was then added and incubated for 5 min and washed in PBS three times. Cells were imaged by light microscopy (EVOS XL, Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK). All samples were run in triplicate per biological replicate (n = 3).

4.6. Alizarin Red-S Assay

Extra-articular mineralisation and non-specific calcium deposition in hFOB 1.19. were determined by Alizarin red-S assay staining (qualitative) followed by extraction of the stained calcium-rich nodules (deposits) for quantification by spectrophotometry. Cells were washed twice with PBS before fixing with 4% PFA solution and incubated at RT for 20 min. Cells were washed twice, stained with 40 mM Alizarin red-S (pH 4.2) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, A5533) and incubated on a shaker for 85 min (protected from light). Cells were washed twice with PBS for 5 min each with fresh PBS added for imaging, using a light microscope (EVOS XL, Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK). For quantification, cells were lysed with 10% acetic acid for 30 min at RT, transferred into 1.5 mL tubes, heated at 85 °C for 10 min, centrifuged at 20,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C. The lysed cells were then neutralized with 10% ammonium hydroxide for assaying. Absorbance was read at optical density (OD) 405 nm (FLUOstar Omega, BMG LabTech, Aylesbury, Shropshire, UK). The concentration of alizarin red-S (µg/L) was determined according to the linear regression equation derived from the standard curve. All samples were run in triplicate per biological replicate (n = 3).

4.7. Alkaline Phosphatase Assay

Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP; ab83371, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as a marker of osteogenesis and a characteristic indicator of osteoblastic growth and was performed as per manufactures instructions. Briefly, 4-methylumbelliferyl (4-MU) phosphate disodium salt (MUP; 50 μM) reaction mix was added to each well of a 96 well plate. Cell culture supernatant was diluted 1:15 in PBS before adding to reaction mix and incubated for 30 min at RT, protected from light. Stop solution was added and fluorescence was measured spectrophotometrically (FLUOstar Omega, BMG LabTech, Aylesbury, Shropshire, UK), excitation 355 nm and emission 460 nm. Generated 4-MU was calculated according to the linear regression equation derived from the standard curve. All samples were run in triplicate per biological replicate (n = 3).

4.8. Pro-Inflammatory Assessment

The concentration of (pro-)inflammatory mediators released into the medium was measured via Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). IL-1β was used as a positive (pro)-inflammatory control at 10 ng/mL added to both the apical and basal side of the culture. Cell culture supernatant was collected at day 1 and 7 after treatment and analysed for IL-8 (Cat no. DY208) and IL-6 (Cat no. DY206) using DuoSet kits from R&D systems (Bio-techne, Abingdon, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were run in triplicate per biological replicate (n = 3) and absorbance was measured at 450 nm with background correction at 570 nm. Extrapolation of IL-6 and IL-8 concentration was carried out using a four-parameter logistic curve using Graphpad PRISM (Version 10.0.3).

4.9. Total RNA Isolation, Quantification and Reverse Transcription PCR

Following treatments, total RNA was extracted from co-culture using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Ltd., Surrey, UK) as per manufactures instructions. The amount and quality of RNA [optical density (OD) ratio 260/280 > 1.8, OD ratio 230/280 > 1.7] was measured using a Nanophotometer (IMPLEN, Munich, Germany). Total RNA (1000 ng/μL) was converted to cDNA using the iScript™ gDNA Clear cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK) as per manufactures instructions with a final reaction volume of 20 µL. The reaction volume was incubated on the T100 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK) for 5 min at 25 °C, then at 46 °C for 20 min and finally 95 °C for 1 min. cDNA (1:10 dilution) was added to predesigned Human Osteoarthritis H96 qPCR Arrays in a 96-well format using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK) in duplicate as per manufactures instructions and using the Bio-Rad CFX connect (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK). Gene expression data was calculated using the ΔΔCq method. Data was normalized to three reference genes (HPRT1, GAPDH, TBP) using Bio-Rad CFX Maestro Data Analysis software (Version 2.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK). Litho samples were then compared to OA model (IL-1β CM) for changes in gene expression. Results were plotted in GraphPad prism software (Version 10.0.3) as Fold Change using mean ± SEM.

Informed by array data and literature review, a panel of genes were selected for confirmatory analysis by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). All primers and reagents were purchased from Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK). The ddPCR assays were performed on the same cDNA samples previously mentioned. For ddPCR, the final reaction volume was 20 μL, which included cDNA mix, 2X ddPCR Supermix for probes (no dUTP), 20x target probe FAM, 20x target probe HEX and RNase free H2O. All primer probes were predesigned and purchased from Bio-Rad; COL1A1 (HEX), C1qTNF2 (FAM), IL-6 (FAM), PTGS2 (HEX), CCL2 (FAM), TNFSF10 (HEX), TGFB3 (HEX), PTDGS (FAM). The droplet generation and reading were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 70 μL of probe droplet generation oil was added. The water-in-oil droplet emulsion was prepared using the QX200 Droplet Generator (Bio-Rad). The amplification step was performed using 40 μL of emulsion in a C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Ltd., Watford, UK). The ddPCR reactions were analysed using the QX200 Droplet Reader and QuantaSoft software version 1.7.4 (both from Bio-Rad).

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), fold change and copies/μL were applicable. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality of each data set. For normally distributed characteristics and ELISAs, either one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; ARZ and ALP), t-tests (COL1A1 and untreated viability) or two-way ANOVA (IL-6, IL-8 and treated cell viability) were performed. For normally distributed gene expression data, t-tests were performed for unstimulated vs. unstimulated (IL-1β CM) (COL1A1, IL-6, CIQTNF2 and PTGS2 (day 7)) or for nonparametric data Mann-Whitney U was performed (PTGS2 (day 1)). For treatment comparisons of gene expression data, either two-way ANOVA (COL1A1, IL-6, CIQTNF2, PTGS2 (day 7) and TNFSF10) with Tukey or Dunnetts post hoc was applied, unless otherwise stated. For nonparametric data Kruskal-Wallis was used (PTGS2 (day 1) and CIQTNF2 (day 1)). Gene expression array data was presented as normalised fold change. All null-hypothesis tests were performed in Graphpad PRISM (Version 10.0.3) with alpha set at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

This study presents for the first time a replicable 2D co-culture model of inflammatory OA for investigations of bioactive nutraceuticals. The model showed that one such nutraceutical, Litho, reduced the expression of inflammatory and pain related genes, and demonstrated for the first time altered expression of C1QTNF2 (CTRP2) in a human OA model. The precise role of C1QTNF2 in OA is unknown and the potential for Lithothamnion species to modify its expression warrants further investigation. These data and the present model can be used to further investigate if Lithothamnion species and other bioactive nutraceuticals can be used in tandem with pharmaceutical treatments to act synergistically. This could show the potentially for bioactive nutraceuticals to reduce the dosages of harmful often-synthetic pharmaceuticals and if they could potentially lead to reduced incidence of adverse side effects currently being experienced by OA patients during treatment.

Author Contributions

S.M.H. and G.E.C. designed the initial concept and S.M.H., G.E.C. and M.W. refined the study design. S.M.H. and G.E.C. executed the experimental procedures with specific technical expertise from K.M. and S.J.E. S.M.H. and G.E.C. drafted the initial manuscript, data analysis and presentation and all authors were involved in subsequent drafting and approval of the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by Nordic Medical Ltd., Office A303-4, Tower Bridge Business Complex, 100 Clements Road, London, SE16 4DG (Grant code 106381), the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales RWIF fund (Grant code #EE16) and institutionally via Swansea University, Applied Sports Science Technology and Medicine Research Centre. KM would like to acknowledge salary funding from the UKRI RESPIRE study (Grant No. NE/W002264/1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

SH: G.C. and M.W. have received funding from Marigot Ltd., a separate Algae extract supply company. The authors have no further conflicts to declare.

References

- Hiligsmann, M.; Cooper, C.; Arden, N.; Boers, M.; Branco, J.C.; Brandi, M.L.; Bruyère, O.; Guillemin, F.; Hochberg, M.C.; Hunter, D.J. Health economics in the field of osteoarthritis: An expert’s consensus paper from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 43, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. Eclin. Med. 2020, 29, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Culbreth, G.T.; Haile, L.M.; Rafferty, Q.; Lo, J.; Fukutaki, K.G.; Cruz, J.A.; Smith, A.E.; Vollset, S.E.; Brooks, P.M. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e508–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1545–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; March, L.; Chew, M. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: A Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 1711–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Network Collaborative. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. Available online: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Lane, N.E.; Brandt, K.; Hawker, G.; Peeva, E.; Schreyer, E.; Tsuji, W.; Hochberg, M.C. OARSI-FDA initiative: Defining the disease state of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, D.B.; Gallant, M.A. Bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, M.B.; Otero, M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2011, 23, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attur, M.; Krasnokutsky, S.; Statnikov, A.; Samuels, J.; Li, Z.; Friese, O.; Hellio Le Graverand-Gastineau, M.P.; Rybak, L.; Kraus, V.B.; Jordan, J.M.; et al. Low-grade inflammation in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: Prognostic value of inflammatory plasma lipids and peripheral blood leukocyte biomarkers. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 2905–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusup, A.; Kaneko, H.; Liu, L.; Ning, L.; Sadatsuki, R.; Hada, S.; Kamagata, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Futami, I.; Shimura, Y.; et al. Bone marrow lesions, subchondral bone cysts and subchondral bone attrition are associated with histological synovitis in patients with end-stage knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 1858–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenbaum, F.; van den Berg, W.B. Inflammation in osteoarthritis: Changing views. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2015, 23, 1823–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Nevitt, M.; Niu, J.; Lewis, C.; Torner, J.; Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.; McCulloch, C.; Felson, D.T. Fluctuation of knee pain and changes in bone marrow lesions, effusions, and synovitis on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffernan, S.M.; Conway, G.E.; McCarthy, C.; Eustace, S.; Waldron, M.; De Vito, G.; Delahunt, E. Inflammatory markers in early knee joint osteoarthritis differ from well-matched controls and are associated with consistent, rather than intermittent knee pain. Knee 2024, 51, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thijssen, E.; Van Caam, A.; Van Der Kraan, P.M. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: Pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, F.; Barone, E.; Sica, A.; Selmi, C. Inflammaging and Osteoarthritis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, H.P.; Galvin, R.; Horgan, N.F.; Kenny, R.A. Prevalence and burden of osteoarthritis amongst older people in Ireland: Findings from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Lopez, A.D.; World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 1, p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Kopec, J.A.; Sayre, E.C.; Schwartz, T.A.; Renner, J.B.; Helmick, C.G.; Badley, E.M.; Cibere, J.; Callahan, L.F.; Jordan, J.M. Occurrence of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee and hip among African Americans and whites: A population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2013, 65, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, I.J.; Worthington, S.; Felson, D.T.; Jurmain, R.D.; Wren, K.T.; Maijanen, H.; Woods, R.J.; Lieberman, D.E. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9332–9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tunen, J.A.C.; Peat, G.; Bricca, A.; Larsen, L.B.; Søndergaard, J.; Thilsing, T.; Roos, E.M.; Thorlund, J.B. Association of osteoarthritis risk factors with knee and hip pain in a population-based sample of 29-59 year olds in Denmark: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latourte, A.; Kloppenburg, M.; Richette, P. Emerging pharmaceutical therapies for osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, R.S.; Hall, M.; Comensoli, S.; Bennell, K.L. Exercise & Sports Science Australia (ESSA) updated Position Statement on exercise and physical activity for people with hip/knee osteoarthritis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffernan, S.M.; Conway, G.E. Nutraceutical Alternatives to Pharmaceutical Analgesics in Osteoarthritis. In Pain Management—Practices, Novel Therapies and Bioactives; Waisundara, V.Y., Banjari, I., Balkić, J., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudian, A.; Lohmander, L.S.; Mobasheri, A.; Englund, M.; Luyten, F.P. Early-stage symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee—Time for action. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Mathieson, S.; Kobayashi, S.; Abdel Shaheed, C.; Nogueira, L.A.C.; Simic, M.; Machado, G.; McLachlan, A.J. Prevalence of Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs Prescribed for Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Arthritis Care Res 2023, 75, 2345–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, J.P.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Rannou, F.; Cooper, C. Efficacy and safety of oral NSAIDs and analgesics in the management of osteoarthritis: Evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 45, S22–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, M.; Driban, J.; McAlindon, T. Pharmaceutical treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Driest, J.J.; Pijnenburg, P.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Schiphof, D. Analgesic Use in Dutch Patients With Osteoarthritis: Frequent But Low Doses. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlund, J.B.; Turkiewicz, A.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Englund, M. Inappropriate opioid dispensing in patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis: A population-based cohort study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2020, 28, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harirforoosh, S.; Asghar, W.; Jamali, F. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: An update of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal complications. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 16, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, B.R.; Reichenbach, S.; Keller, N.; Nartey, L.; Wandel, S.; Juni, P.; Trelle, S. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis. Lancet 2017, 390, e21–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.; Salvo, F.; Duong, M.; Gulmez, S.E. Does paracetamol still have a future in osteoarthritis? Lancet 2016, 387, 2065–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, J.C.; Morrison, E.E.; MacIntyre, I.M.; Dear, J.W.; Webb, D.J. Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol—A review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2218–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Delgado Nunes, V.; Buckner, S.; Latchem, S.; Constanti, M.; Miller, P.; Doherty, M.; Zhang, W.; Birrell, F.; Porcheret, M.; et al. Paracetamol: Not as safe as we thought? A systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.; Thor, H.; Moore, G.; Nelson, S.; Moldéus, P.; Orrenius, S. The toxicity of acetaminophen and N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine in isolated hepatocytes is associated with thiol depletion and increased cytosolic Ca2+. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 13035–13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; McGill, M.R.; Du, K.; Dorko, K.; Kumer, S.C.; Schmitt, T.M.; Ding, W.X.; Jaeschke, H. Mitochondrial protein adducts formation and mitochondrial dysfunction during N-acetyl-m-aminophenol (AMAP)-induced hepatotoxicity in primary human hepatocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015, 289, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, I.N.; Zomer, E.; Gilmartin-Thomas, J.F.; Liew, D. Forecasting the future burden of opioids for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2018, 26, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsch, P.; Petzke, F.; Klose, P.; Häuser, W. Opioids for chronic osteoarthritis pain: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, tolerability and safety in randomized placebo-controlled studies of at least 4 weeks double-blind duration. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osani, M.C.; Lohmander, L.S.; Bannuru, R.R. Is There Any Role for Opioids in the Management of Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuggle, N.; Curtis, E.; Shaw, S.; Spooner, L.; Bruyère, O.; Ntani, G.; Parsons, C.; Conaghan, P.G.; Corp, N.; Honvo, G.; et al. Safety of Opioids in Osteoarthritis: Outcomes of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drugs Aging 2019, 36 (Suppl. 1), 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Eyles, J.; McLachlan, A.J.; Mobasheri, A. Which supplements can I recommend to my osteoarthritis patients? Rheumatology 2018, 57 (Suppl. 4), iv75–iv87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Machado, G.C.; Eyles, J.P.; Ravi, V.; Hunter, D.J. Dietary supplements for treating osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrotin, Y.; Mobasheri, A. Natural Products for Promoting Joint Health and Managing Osteoarthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2018, 20, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharz, E.J.; Kovalenko, V.; Szántó, S.; Bruyère, O.; Cooper, C.; Reginster, J.-Y. A review of glucosamine for knee osteoarthritis: Why patented crystalline glucosamine sulfate should be differentiated from other glucosamines to maximize clinical outcomes. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016, 32, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, M.; McConnell, S.; Harmer, A.R.; Van der Esch, M.; Simic, M.; Bennell, K.L. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: A Cochrane systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1554–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, R.; Lim, S.; Steen, R.G.; Dasa, V. Hyaluronic Acid Injections Are Associated with Delay of Total Knee Replacement Surgery in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: Evidence from a Large U.S. Health Claims Database. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlindon, T.E.; Bannuru, R.R.; Sullivan, M.C.; Arden, N.K.; Berenbaum, F.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Hawker, G.A.; Henrotin, Y.; Hunter, D.J.; Kawaguchi, H.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.P.; Moses, J.C.; Bhardwaj, N.; Mandal, B.B. Overcoming the Dependence on Animal Models for Osteoarthritis Therapeutics—The Promises and Prospects of In Vitro Models. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2100961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Krishna, M. Alternative in vitro models for safety and toxicity evaluation of nutraceuticals. In Nutraceuticals, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, S.M.; McCarthy, C.; Eustace, S.; FitzPatrick, R.E.; Delahunt, E.; De Vito, G. Mineral rich algae with pine bark improved pain, physical function and analgesic use in mild-knee joint osteoarthritis, compared to Glucosamine: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 50, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.T.; Martin, C.; Doolan, A.M.; Molloy, M.G.; Dinan, T.G.; Gorman, D.; Nally, K. The Marine-derived, Multi-mineral formula, AquaPT Reduces TNF-α Levels in Osteoarthritis Patients. J. Nutr. Health Food Sci. 2014, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Frestedt, J.L.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Zenk, J.L. A natural seaweed derived mineral supplement (Aquamin F) for knee osteoarthritis: A randomised, placebo controlled pilot study. Nutr. J. 2009, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frestedt, J.L.; Walsh, M.; Kuskowski, M.A.; Zenk, J.L. A natural mineral supplement provides relief from knee osteoarthritis symptoms: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Nutr. J. 2008, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.; O’Gorman, D.M.; Nolan, Y.M. Evidence that the marine-derived multi-mineral Aquamin has anti-inflammatory effects on cortical glial-enriched cultures. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, D.M.; O’Carroll, C.; Carmody, R.J. Evidence that marine-derived, multi-mineral, Aquamin inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway in vitro. Phytother. Res. PTR 2012, 26, 630–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renaud, J.; Martinoli, M.G. Development of an Insert Co-culture System of Two Cellular Types in the Absence of Cell-Cell Contact. J. Visulised Exp. 2016, 113, e54356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, C.; Jordan, O.; Allémann, E. Osteoarthritis In Vitro Models: Applications and Implications in Development of Intra-Articular Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolotti, I.; Roseti, L.; Petretta, M.; Grigolo, B.; Desando, G. A Roadmap of In Vitro Models in Osteoarthritis: A Focus on Their Biological Relevance in Regenerative Medicine. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gorman, D.M.; Naderi, Z.; Yeganeh, A.; Malboosbaf, R.; Eriksen, E.F. Disease-Modifying Adjunctive Therapy of Osteopenia and Osteoporosis with a Multimineral Marine Extract, LithoLexal® Bone. Osteology 2023, 3, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, E.F.; Lech, O.; Nakama, G.Y.; O’Gorman, D.M. Disease-Modifying Adjunctive Therapy (DMAT) in Osteoarthritis-The Biological Effects of a Multi-Mineral Complex, LithoLexal(®) Joint-A Review. Clin Pract. 2021, 11, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, V.D.; O’Gorman, D.M.; O’Brien, N.M.; Hyland, N.P. Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of a Marine-Derived Multimineral, Aquamin-Magnesium. Nutrients 2018, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.N.; Kreider, J.M.; Paruchuri, T.; Bhagavathula, N.; DaSilva, M.; Zernicke, R.F.; Goldstein, S.A.; Varani, J. A mineral-rich extract from the red marine algae Lithothamnion calcareum preserves bone structure and function in female mice on a Western-style diet. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2010, 86, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Xu, P.; Sun, S.; Zhao, Z.; Tan, Q.; Li, W.; Song, C.; Leng, H. Cellular alterations and crosstalk in the osteochondral joint in osteoarthritis and promising therapeutic strategies. Connect. Tissue Res. 2021, 62, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Nicoll, S.B.; Lu, H.H. Co-culture of osteoblasts and chondrocytes modulates cellular differentiation in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 338, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegertjes, R.; van de Loo, F.A.J.; Blaney Davidson, E.N. A roadmap to target interleukin-6 in osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 2681–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maekawa, A.; Sawaji, Y.; Endo, K.; Kusakabe, T.; Konishi, T.; Tateiwa, T.; Masaoka, T.; Shishido, T.; Yamamoto, K. Prostaglandin E(2) induces dual-specificity phosphatase-1, thereby attenuating inflammatory genes expression in human osteoarthritic synovial fibroblasts. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2021, 154, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.E.; Miller, R.J.; Malfait, A.M. Osteoarthritis joint pain: The cytokine connection. Cytokine 2014, 70, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yin, D.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, X. Abrine promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of interleukin-1β-stimulated chondrocytes via PIM2/VEGF signalling in osteoarthritis. Phytomedicine 2022, 96, 153906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.; Li, Q.; Zhao, C. Interleukin 1β and tumor necrosis factor α promote hFOB1.19 cell viability via activating AP1. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces de Los Fayos Alonso, I.; Liang, H.C.; Turner, S.D.; Lagger, S.; Merkel, O.; Kenner, L. The Role of Activator Protein-1 (AP-1) Family Members in CD30-Positive Lymphomas. Cancers 2018, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Ma, B.; Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, M.; Wang, D. Cytokine networking of chondrocyte dedifferentiation in vitro and its implications for cell-based cartilage therapy. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2015, 7, 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro-Ramil, M.; Sanjurjo-Rodríguez, C.; Rodríguez-Fernández, S.; Hermida-Gómez, T.; Blanco-García, F.J.; Fuentes-Boquete, I.; Vaamonde-García, C.; Díaz-Prado, S. Generation of human immortalized chondrocytes from osteoarthritic and healthy cartilage: A new tool for cartilage pathophysiology studies. Bone Jt. Res. 2023, 12, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlier, E.; Deroyer, C.; Ciregia, F.; Malaise, O.; Neuville, S.; Plener, Z.; Malaise, M.; de Seny, D. Chondrocyte dedifferentiation and osteoarthritis (OA). Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 165, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyh, C.; Krüger, K.; Peeling, P.; Castell, L. The Role of Minerals in the Optimal Functioning of the Immune System. Nutrients 2022, 14, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Qin, H.; An, Z. Magnesium enhances the chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting activated macrophage-induced inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, S.; Kubota, Y.; Satoh, S.; Ito, S.; Takeuchi, H.; Ashizuka, M.; Shirasuna, K. Ca2+ stimulates COX-2 expression through calcium-sensing receptor in fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 351, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, A.; Deres, L.; Sumegi, B.; Toth, K.; Szabados, E.; Halmosi, R. Cardioprotective Effect of Resveratrol in a Postinfarction Heart Failure Model. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 6819281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Qu, W.; Wang, X.; Su, H.; Li, W.; Xu, W. Amentoflavone alleviated cartilage injury and inflammatory response of knee osteoarthritis through PTGS2. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 8903–8916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastbergen, S.C.; Lafeber, F.P.; Bijlsma, J.W. Selective COX-2 inhibition prevents proinflammatory cytokine-induced cartilage damage. Rheumatology 2002, 41, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yue, J.; Yang, C. Unraveling the role of Mg++ in osteoarthritis. Life Sci. 2016, 147, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.-P.; Jia, J.-F.; Wang, P. Dietary magnesium ions block the effects of nutrient deficiency on inducing the formation of LC3B autophagosomes and disrupting the proteolysis of autolysosomes to degrade β-amyloid protein by activating cyclooloxygenase-2 at tyrosine 385. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 83, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanbacher, C.; Hermanns, H.M.; Lorenz, K.; Wajant, H.; Lang, I. Complement 1q/Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Proteins (CTRPs): Structure, Receptors and Signaling. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang-Sun, Z.Y.; Xue, C.X.; Li, X.Y.; Ren, J.; Jiang, Y.T.; Liu, T.; Yao, H.R.; Zhang, J.; Gou, T.T.; et al. CTRP family in diseases associated with inflammation and metabolism: Molecular mechanisms and clinical implication. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.M.; Doss, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Multifaceted Physiological Roles of Adiponectin in Inflammation and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barmoudeh, Z.; Shahraki, M.H.; Pourghadamyari, H.; Borj, M.R.; Doustimotlagh, A.H.; Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi, K. C1q tumor necrosis factor related proteins (CTRPs) in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Acta Biochim. Iran. 2023, 1, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).