Current Trends in Urban Heritage Conservation: Medieval Historic Arab City Centers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Arab Historic City Centers

2.1. Characteristics of Arab Historic City Centers

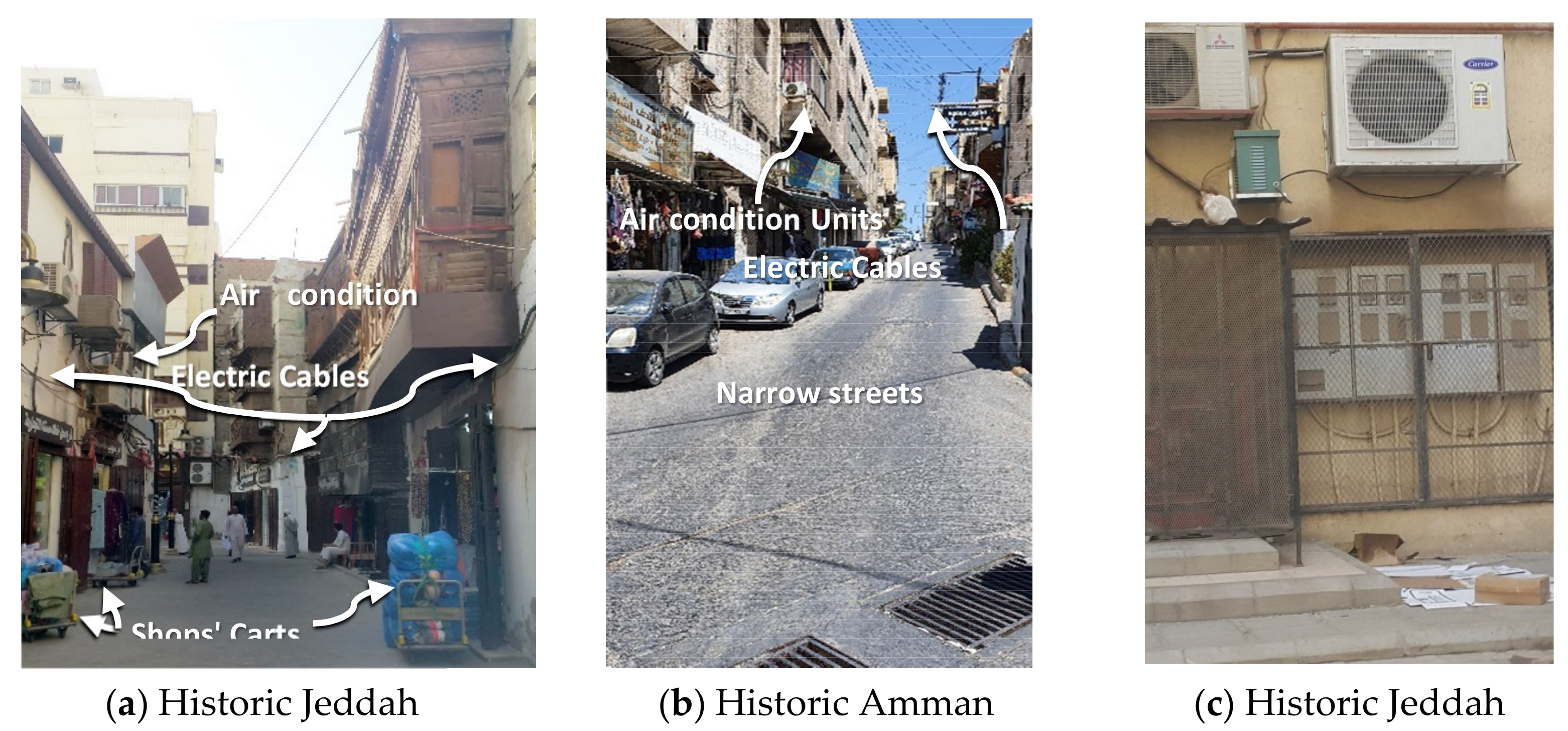

2.2. Endangered Arab Historic City Centers

2.3. Urban Problems of Arab Historic Centers

3. Theoretical Background and Contextual Approach

3.1. Evolution of Heritage Definition

3.2. Historic Urban Landscape Approach (HUL)

3.3. Urban Heritage

3.4. Urban Heritage Conservation (UHC)

4. Methodology and Assessment Framework

- As concluded from the theoretical background, five aspects of the UHC project have to be accomplished through twenty practices. Each one of these development practices has an impact on the success of the resulting urban heritage. These practices comprise the table header.

- Urban quality attributes, representing the development success, fell into seven main areas and can be estimated through thirty-three indicators. These quality indicators constitute the table rows.

- The proposed relation between practices and quality indicators is categorized into five different shades; the darker color represents a strong impact and has a weight of five, while the lighter shade represents a lower impact and has the value of one.

5. Case Studies

5.1. Amman City

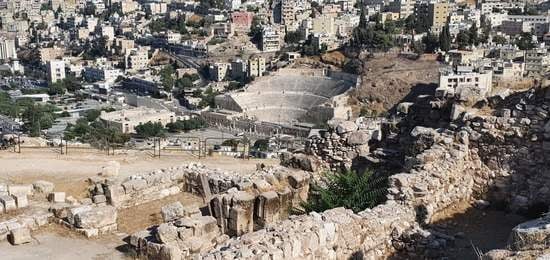

5.1.1. Amman Historical Center “Albalad”

5.1.2. Conservation Activities

5.1.3. Current Urban Management Plans

- Re-establish the Albalad as a commercial destination by conserving the existing traditional market’s character. Regulate the informal street retailers to achieve a vibrant street mall with good urban design qualities and enhance the specialized and thematic commercial areas.

- Define cultural heritage buildings and districts. Conserve and adapt the reuse of heritage buildings. Implement guidelines for heritage protection and encourage artistic and cultural activities.

- Establish connections between the public realm and its surrounding areas through pedestrian and public transport routes and public and commercial spaces. Improve the image quality of public space and create gateways and thematic landmarks.

- Preserve the existing urban physical character in form and visual relationship with surrounding hilltops.

- Support tourism by enhancing the heritage district spirit, defining the tourist pedestrian routes, and providing tourist services and cultural activities.

- Create an entertaining district by establishing a mixed-use character of specialty retail, cafes, and restaurants. At the same time, make arrangements to hold entertainment venues, festivals, and cultural events.

5.1.4. Impact of Implemented Development Actions

| Area | Assessment |

|---|---|

| Environment | Adaptive reuse: Commercial ground floors spread evenly through the narrow allays as using first floors as cafes and restaurants attracted more visitors shown in Figure 10 Traditional food and specialized cafes and restaurants and gift shops and bazaars are the majority of the ground floor uses, as shown in the map in Figure 11. At the same time, some famous restaurants are situated on the first floor, as shown in Figure 10. The number of visitors: As the COVID-19 pandemic impacts started to decrease, the area flourished with visitors from other cities and regions. The statistics revealed a 30% increase in tourists’ numbers between 2016 and 2019 [49]. Photos in Figure 12 show the vibrant spaces of the city. Energy consumption: Despite that the area climate is considered moderate, adding decorative lights throughout the streets is shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13. Extending the working hours for the commercial area increases the electricity consumption. Pollution: Adding a ring road and two central stations and arranging an internal taxi shuttle service helped ease traffic congestion within the area and reduce air pollution. Preserving the ever-green trees improved the visual and environmental qualities of the area. |

| Economic | Local Businesses Share: Statistics are not available at this stage. Average Rent: Hotel rooms’ rent varies at 150–250 JD. Exact statistics are not available at this stage. Tourism sector size: Statistics are not available at this stage. |

| Social | Average income: Lower-middle-class income is 4850 JD average income while poverty line is above 3737 JD statistics within the area ranges is not available at this stage. [50] Unemployment rates: Department of Jordanian statistics show that the unemployment rate in Amman in 2021 in the second quarter was 24.8% [49] Crime rate: Not available at this stage.The number of job opportunities: One of the objectives of the area development was to create jobs. [48]. The ongoing development of the Albalad allowed Hawkers to use the sidewalks to create more jobs, as shown in Figure 14. Sense of belonging: Many residents do not originate in the city and have no sense of belonging; they still enjoy the center and benefit economically, as shown in Figure 15. Sense of pride: Native residents are not happy with the rising refugee numbers because they share their services and the limited job opportunities. Volunteer hours: Statistics are not available at this stage. |

| Services | Shopping: Traditional food, touristic gift shops, cultural events, and cleanly maintained walkways give the public spaces a vibrant image, as illustrated in Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16. Restaurants and Cafes: As per the land use map in Figure 11 Seating areas: Publish seating areas are limited, but outdoor cafes are distributed on the main streets and the stepped alleys. Public toilets: No public toilets except the Mosques and restaurants. Shaders: All the alleys have shaders with different designs and formations. Figure 17 illustrates some of these shading units. |

| Accessibility and Linkage | Public transportation: The area has a taxi shuttle service and two main public transportation stations to link the area to the city districts. Parking lots: There is parking on the streets and parking lots near the two newly refurbished stations. Pedestrian-friendly: The walkways are separated from the cars Clear wayfinding: Streets’ slopes and surrounding hills make clear landmarks for visitors. These slops make it easy to move around. Connection to nearby districts and services: The neighboring areas are mainly on the surrounding slopes, meaning the linkage is not direct or easy. |

| Culture and image | Rainstorm drainage: The area is a valley surrounded by hills. Several projects to make the best use of the floodwater. Garbage collection: The area is serviced by an effective garbage collection system. Floor Finishing: Walkways using finishing are not expensive, but their details are well designed and constructed. Maintained buildings: Archeological sites lack services, and their surroundings are not well-maintained, as shown in Figure 10, which exhibits the physical conditions of the nearby Castel mountain archeological site. Preserving the contours helped to maintain the original character of the Albalad area Figure 18. Moreover, limiting the building heights to three or four floors maintained the visual contact with the surrounding hilltops and the ratios of the width of the spaces to their surrounding buildings, as presented in Figure 13. Preserving the ever-green trees improved the visual and environmental qualities of the spaces. Streetscape: Walking around gives a rich visual experience either day or night, despite some visual pollution resulting from the suspended electric cables and shops signs with different colors and sizes. |

| Infrastructure | Electricity: The area is covered by electricity. Electric cables are suspended along the many streets within the area. Bootable Water: The area is served by a water network despite the issue of hell areas. Drainage: The area is covered by a sewerage network despite the issue of hell areas. Communication: There is well covered by phone and internet service. |

5.2. Jeddah City

5.2.1. Jeddah Historical Center

5.2.2. Conservation Activities

5.2.3. Current Urban Management Plans

5.2.4. Impact of Implemented Development Actions

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- The proposed assessment framework showed that conservation parameters could be assessed through the resulting urban qualities.

- The presented parameters of Urban Heritage Conservation need to be defined and followed from the early stages of the project.

- A set of assessment indicators needs to be defined as soon as the strategic vision is identified. The proposed framework provides a good base for such an assessment process.

- It has been proven that the conservation efforts of most Arab cities’ historical centers are outdated in benefiting from the historic urban landscape approach and intangible cultural assets.

- Case studies’ analysis shows that social activities and heritage-based events can help build a sense of belonging and a sense of place. Seasonal programs with weekly events of various types can bring visitors from different backgrounds to the targeted areas and help promote them. Moreover, it would build the required image of the place.

- Creating outdoor quality spaces is a good step in developing the historic urban area, but it will not bring visitors. Creating activities, adopting new uses for buildings, adding commercial activities, restaurants, cafes, and seating areas can create a vital active place.

- Adaptive reuse for historic buildings should be selected carefully. Such reuse should offer the safety and security of the historic buildings simultaneously; it should support their sustainability. Selected functions could significantly influence the livability and vitality of the open spaces between these buildings.

- Case studies suggested that repeated efforts to accommodate the car traffic systems within the historic urban spaces proved to fail. Creating pedestrian-friendly urban areas contributes positively to safe, less congested, and less polluted urban areas.

- The Amman case study analysis proved that creating a ring road around the area eases traffic congestion and environmental pollution. Providing a mass-transit system linked the area to the neighboring districts. Having parking areas at the area borders contributes to easing traffic.

- The case of Amman proved that having a public transit system for the historic area can encourage visitors to leave their cars on the area’s borders.

- The Jeddah case study showed that the unavailability of mass transit and the enforcement of a paid parking policy along the streets around the area pushed visitors to park their cars inside the historic area narrow alleys causing a congested traffic jam, where pedestrians and vehicles share the same spaces without any separation.

- A legal and economic framework must be defined and put to action before any conservation efforts start. This framework should deal with ownership issues and the buildings’ regulations to guarantee the security of these buildings.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badawy, S.; Shehata, A.M. Sustainable Urban Heritage Conservation Strategies—Case Study of Historic Jeddah Districts. In Cities’ Identity through Architecture and Arts; Anna Catalani, Z.N., Versaci, A., Hawkes, D., Bougdah, H., Sotoca, A., Ghoneem, M., Trapani, F., Eds.; Routledge: Cairo, Egypt, 2020; Volume 1, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saffar, M. Urban heritage and conservation in the historic center of Baghdad. Int. J. Herit. Arch. Stud. Repairs Maint. 2017, 2, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Culture in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda: A Report by Culture 2030 Global Goals Movement. ICOMOS. 2018, p. 2. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Secretariat/2021/SDG/ICOMOS_SDGs_Policy_Guidance_2021.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- UNESCO. Item 12 of the Provisional Agenda: Revision of the Operational Guidelines. In Convention Concerning The Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage—Extended Forty-Fourth Session; 2021; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/173608 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- UNESCO. Adopted decisions during the 42nd session of the World Heritage Committee. In Convention Concerning The Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage-Forty-Second Session; WHC/18/42.COM/18; 2018; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/168796 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Mandeli, K. Interpretation of Urban Design Principles in a Traditional Urban Environment: The Role of Social Values in Shaping Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jasim, S. The Issue of Standardization in Tradition Urban Fabric of Islamic City. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference “Standardization, Prototypes, and Quality: A Means of Balkan Countries’ Collaboration", Brasov, Romania, 3–4 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, R.W. Traditional vs. modern Arabian morphologies. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 2, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasralden, M.K. The Transformation of Public Spaces in Saudi Cities: A Case Study of Jeddah. In Proceedings of the Saudi International Conference, Coventry, UK, 23–26 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, M.L. The Egyptian City Centers in the Islamic Era: Image Analysis, Evaluation, and Contemporary Reflections. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 48, 538–553. [Google Scholar]

- Correia Jorge, M.T. Traditional Islamic Cities Unveiled: The Quest for Urban Design Regularity. Gremium. Mag. 2015, 2. Available online: https://editorialrestauro.com.mx/traditional-islamic-cities-unveiled-the-quest-for-urban-design-regularity/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- AlSayyad, N. Space in an Islamic City: Some Urban Design. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 1987, 4, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, D. The Rights to Amman: An Exploration of the Relationship between a City and Its Inhabitants. Master’s Thesis, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Zhang, Q.; Chan, E.H.W. Underlying social factors for evaluating heritage conservation in urban renewal districts. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, T.; Eğercioğlu, Y. Historic City Center Urban Regeneration: Case of Malaga and Kemeraltı, Izmir. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abu-Hamdi, E. Neoliberalism as a site-specific process: The aesthetics and politics of architecture in Amman, Jordan. Cities 2017, 60, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, Z.O.; Almukhtar, A.; Abanda, H.; Tah, J. Mosul City: Housing Reconstruction after the ISIS War. Cities 2022, 120, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, D.H.I.L. Cairo: An Arab city transforming from Islamic urban planning to globalization. Cities 2021, 117, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnsour, J. Managing urban growth in the city of Amman, Jordan. Cities 2016, 50, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keep, M.; Montanari, B.; Greenlee, A.J. Contesting “inclusive” development: Reactions to slum resettlement as social inclusion in Tamesna, Morocco. Cities 2021, 118, 103328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeljawad, N.; Nagy, I. Urban Environmental Challenges and Management Facing Amman Growing City. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. 2021, 11, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaal, W.A. Large urban developments as the new driver for land development in Jeddah. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaad, A.; Abdelghany, K. The story of five MENA cities: Urban growth prediction modeling using remote sensing and video analytics. Cities 2021, 118, 103393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koorosh, S.S.; Sza, I.; Ahad, F. Evaluating Citizens’ Participation in the Urban Heritage Conservation of Historic Area of Shiraz. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Developing Historic Cities Key Understanding and Taking Actions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, A.G. Sacred Placemaking and Urban Policy the Case of Tepoztlán, Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of California, Irvine, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Fifteenth General Assembly of States Parties to the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zancheti Silvio Mendes, K.S. Measuring Heritage Performance. In Proceedings of the In 6th International Seminar on Urban Conservation, Recife, Brazil, 29–31 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Janset, S. Al-Balad as a Place of Heritage: Problematizing the Conceptualization of Heritage in the Context of Arab Muslim Middle East. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; King, B.; Yeung, E.Y.M. Experiencing culture in attractions, events and tour settings. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesca, N. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development Multidimensional Indicators as Decision Making Tool Enhanced Reader. Sustainability 2017, 9, 28. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape-Report of the Second Consultation on Its Implementation by the Member States; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Centre; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 1–177. [Google Scholar]

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter Process, Flow Chart from the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter. 2013. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Ashour, K.N. Urban Regeneration Strategies in Amman’s Core: Urban Development and Real Estate Market. Ph.D. Thesis, Dortmund Technical University, Dortmund, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrostefani, E.; Holman, N. The politics of conservation planning: A comparative study of urban heritage making in the Global North and the Global South. Prog. Plan. 2020, 152, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapidi, I. Heritage policy meets community praxis: Widening conservation approaches in the traditional villages of central Greece. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 81, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldpaus, L.; Roders, A.P. Historic Urban Landscapes—An Assessment Framework. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Meeting of the International Association for Impact Assessment, Calgary Stampede B.M.O Centre, Calgary, AB, Canada, 13–16 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.T.; Roders, A.P. Cultural Heritage Management, and Heritage (Impact) Assessments. In Proceedings of the Joint CIB W070, W092 & TG72 International Conference on Facilities Management, Procurement Systems, and Public-Private Partnership, Cape Town, South Africa, 23–25 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, K.W.; Choy, L.H.T.; Lee, H.Y. Institutional arrangements for urban conservation. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2018, 33, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samargandi, S. Integral Placemaking in Sensitive Heritage Sites for Successful Cultural Tourism. Master’s Thesis, Effat University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yousof, A.S. Plaza Design Criteria—Applied Study of South East Plaza of the Grand Mosque at Makkah. Master’s Thesis, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata Ahmed, A.E. Impact of Urban Development Policies on the Produced Urban Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Conservation of Architectural Heritage (C.A.H.), Aswan, Egypt, 19–22 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beauregard, R.A.; Marpillero-Colomina, A. More than a master plan: Amman 2025. Cities 2011, 28, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, A.; Turbé, A.; Julliard, R.; Simon, L.; Prévot, A.-C. Outstanding challenges for urban conservation research and action. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanian Department of Statistics. Amman Vital Statistics: Jordan Statistical Yearbook. 2020. Available online: http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/databank/yearbook/YearBook_2020.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Abu-Ghazalah, S. Le Royal in Amman: A new architectural symbol for the 21st century. Cities 2005, 23, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanian Department of Statistics. Tourism Statistics: Jordan Statistical Yearbook. 2020. Available online: http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/products/jordan-statistical-yearbook-2020/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Jordanian Department of Statistics. Population Jordan Statistics. 2018. Available online: http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/databank/yearbook/YearBook_2018.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs. Future Saudi Cities Programme City Profiles Series: Jeddah City Profile; Ministry of Municipal Affairs: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alshoaibi, A. Albeeah Architects and Engineers. In Proposed Urban Strategy Report; Jeddah Governorate: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhari, A.Y. Conservation in the Historic District of Jeddah. In Proceedings of the Redeveloping and Rebuilding Traditional Areas, Boston, MA, USA, 16–20 August 1982; pp. 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Heritage Commission. Executive Summary of State of Conservation Report—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia World Heritage Sites; UNESCO: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mady Mohamed, E.M. Investigating the Environmental Performance of the Wind Catchers in Jeddah. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2018, 177, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Geographic Information Center at Jeddah Minucipality. Map of the Nominated Property and the Buffer Zone of Historic Jeddah; Saudi Heritage Commission: Al Bahah, Saudi Arabia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. State of Conservation: Historic Jeddah, the Gate to Makkah (Saudi Arabia); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.K.N. Public Spaces in a Contemporary Urban Environment: Multi-Dimensional Urban Design Approach for Saudi Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Supreme Commission for Tourism, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. National Tourism: Development Project Phase 1: General Strategy; The Supreme Commission for Tourism: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D.; Petetskaya, K. Heritage-led urban rehabilitation: Evaluation methods and an application in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. City, Cult. Soc. 2021, 26, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. A Framework for Sustainable Heritage Management: A Study of U.K, Industrial Heritage Sites. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Lorne, F.T. Sustainable Urban Renewal and Built Heritage Conservation in a Global Real Estate Revolution. Sustainability 2019, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mandeli, K. Public space and the challenge of urban transformation in cities of emerging economies: Jeddah case study. Cities 2019, 95, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Al-Shomali, M.A. Establishing Evaluation Criteria of Modern Heritage Conservation in Historic City Centers in Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2020, 11, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeaja, C.; Trillo, C.; Awuah, K.G.; Makore, B.C.; Patel, D.A.; Mansuri, L.E.; Jha, K.N. Urban Heritage Conservation and Rapid Urbanization: Insights from Surat, India. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirzakhani, A.; Turró, M.; Jalilisadrabad, S. Key stakeholders and operation processes in the regeneration of historical urban fabrics in Iran. Cities 2021, 118, 103362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigwi, I.E.; Ingham, J.; Phipps, R.; Filippova, O. Identifying parameters for a performance-based framework: Towards prioritising underutilised historic buildings for adaptive reuse in New Zealand. Cities 2020, 102, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayantha, W.M.; Yung, E.H.K. Effect of Revitalisation of Historic Buildings on Retail Shop Values in Urban Renewal: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Heritage Definition | UHC Project Objective | Utilized Strategies | Stakeholders Participation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cultural values | Natural values | Attributes | Geographical setting | Identify | Assess | Conserve | Manage | Local values | Local needs | Regulatory systems | Regulatory measures | Environmental impact assessments | Participation processes | Capacity building | Sustainable socio-economic | Sustainable UHC | Policymaking. | Governance system | Management system | ||

| Social | Average income | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Crime rate | |||||||||||||||||||||

| No. of Job opportunities | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sense of belonging | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Sense of pride | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Voluntary work | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Economic | Local Business Share | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Average Rent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tourism sector size | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Environment | Adaptive reuse | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of visitors | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Energy consumption | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Air pollution | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | Sanitation (Public toilets) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Cafes & Seating | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Shopping | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessibility | Public transport. modes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Parking lots | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pedestrian-friendly | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Image | Rainstorm drainage | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Garbish collection | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Floor Finishings | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Maintained buildings | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Streetscape | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Infrastructure | Electric | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Drainage | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Communication | |||||||||||||||||||||

Strong impact

Strong impact  Moderate impact

Moderate impact  Week impact

Week impact  Very week impact

Very week impact  .

.| Area of Assessment | Assessment |

|---|---|

| Environmental | Adaptive Reuse: Selecting commercial ground floor and offices as adaptive reuse for the historical buildings did not work well because they did not meet the requirements for a well-equipped environment for modern office buildings. The whole floor above the ground turned into a store and housing for shops’ workers. They put the valuable buildings at risk of repeated fires and did not bring the expected users. Figure 25 illustrates commercial activities in the Aljamea streets Number of Visitors: The area has been the whole city market, and increasing the commercial area attracted more shoppers. Annual events such as the Ramadan month cultural festival brought different categories of visitors (looking for entertainment visitors rather than shoppers) Energy consumption: Although these historic buildings were designed to utilize passive systems, heavy air-conditioning systems can be noticed, as shown in Figure 2a. Pollution: Creating paid parking along the surrounding streets pushed shop owners and shoppers to use the narrow alleys to make a full-time traffic-congested zone. This traffic congestion increased air temperature, heat, and air pollution. |

| Economic | Local Businesses Share: The area receives many shoppers, the wholesale market of many products such as honey, makeup, clothes, spices, stationeries, and gifts. Exact statistics are not available at this stage Average Rent: Even though the area is viewed as the old cheap market, the area’s rent is considered the highest within the surrounding districts. It ranges between 2500 and 3500 SR per meter a month. Tourism sector size: The area does not attract tourists but shoppers; conservation does not impact visitors’ numbers. The exact visitors’ statistics are not available at this stage. |

| Social | Average income: The native residents deserted the area and rented their properties to froggier merchants. There are no available statistics for income. Unemployment rats: There are no available statistics for income. Crime rate: There are no available statistics for income. The number of Job opportunities: Conservation did not impact the area’s job opportunity. Sense of belonging: Current area residents do not originate in the city and have no sense of belonging; they still benefit as shop vendors. Nevertheless, survey visitors of the Ramadan festival visit the area several times during the month, implying that their sense of belonging increased [60]. Sense of pride: Ramadan festival brought old residents back to the area, and the new generation started to be aware of their inherited culture in food, art, and traditions. Figure 26 illustrates Ramadan festival celebrations. Volunteer hours: There are no statistics for volunteers, but the government started a national program for volunteer work with good incentives. It is expected to boost the volunteer work in the area’s conservation efforts. |

| Accessibility and linkage | Public transportation: The area is not covered by any public transportation. The city is studying different modes of public transportation that cover the whole city, including the Albald historic district. Parking lots: There is multi-story car parking, and visitors use some empty lots as parking. It is worth mentioning that the municipality decided to put parking meters on the streets surrounding the area. This creates a continuous traffic jam within the area’s narrow streets, as shown in Figure 27. Pedestrian-friendly: The street network is mostly pedestrian-oriented. The municipality created vehicle access through a small number of the alleys to produce the needed services for the residents. Clear wayfinding: Wayfinding is not an easy task since the visual character has not been studied before. Connection to nearby districts and services: The area is well connected to the surrounding districts, especially the neighboring old shopping malls. |

| Culture and Image | Shopping: The area is considered the wholesale market. Conservation did not attract any other new commercial activities. Restaurants and Cafes: Conservation efforts did not create any food or cafes commercial activities. Seating areas: New seating areas next to some of the restored buildings were added. Public toilets: The only available toilets are within the mosques or the neighboring shopping malls. Shaders: The narrow alleys are already shaded, and there is no need for extra shaders. |

| Cultural | Rainstorm drainage: The area has no rain drainage system; this caused the shops’ owners much trouble during the last years when the city received more heavy rains than usual. Garbage collection: There is a garbage collection system, but it is not well-managed. Sometimes, in specific locations, garbage accumulates. Floor Finishing: The whole area was covered with granite tiles, which gives the area richness and a good image, as illustrated in Figure 28. Maintained buildings: The buildings have a unique architectural style, and the in-between urban spaces and their composition is one of the oldest and most unique in the region. Figure 29 illustrates the sample of the neglected deteriorated buildings, while Figure 30 shows a sample of the authority’s efforts to maintain it. Streetscape: Cleanly tiled alleys, stylish lighting units, and unified shop signs give the visitors a good impression, as in Figure 28. |

| Infrastructure | Electricity: The area is covered with electricity, but the buildings could not accommodate the transformers. Suspended cables and outdoor transformers could be seen along the alleys. Bootable Water: The whole area is connected to the municipality network. Drainage: The area is connected to the sewerage network, but there is no rain drainage, and the residents complained about the repeated sewerage problems. Communication: The area is covered with a good network for both internet and phones. |

| Recommendation | Anticipated Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Management recommendations | 1. | Adopt a participatory approach for conservation, engaging related national and local institutions and all stakeholders. | Ensure achieving support from related stakeholders. |

| 2. | Develop a strategic vision and phased action plan for the city, including the historic center. | Ensure clear objectives and sustainable phased development. | |

| 3. | Define heritage conservation and development measurable objectives. | Ensure good assessment and feedback for corrections. | |

| 4. | Define assessment indicators for assessment in the early phases of the project | Provide good reliable feedback for the project management. | |

| 5. | Data collection of existing conditions must be conducted before development implementation. | Developed KPIs can be measured, and conservation efforts can be assessed and adjusted. | |

| Execution recommendations | 6. | Arrange social activities and cultural events programs. Engage residents in the urban management plans process. | Increase sense of belonging and pride; create a local driving force for the development plans. |

| 7. | Engage residents in identifying the heritage and categorizing its value. | Increased sense of belonging and creating a driving force for preserving the heritage asset. | |

| 8. | Select the adaptive reuse of historical buildings carefully. | New usage can attract visitors and boost the local economy. | |

| 9 | Follow a sustainable multidirectional UHC. | Ensure the sustainability of the development. | |

| 10 | Create a car-free historic area and make it pedestrian-friendly. | Create an excellent urban image of a safe, less polluted urban environment. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shehata, A.M. Current Trends in Urban Heritage Conservation: Medieval Historic Arab City Centers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020607

Shehata AM. Current Trends in Urban Heritage Conservation: Medieval Historic Arab City Centers. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020607

Chicago/Turabian StyleShehata, Ahmed Mohamed. 2022. "Current Trends in Urban Heritage Conservation: Medieval Historic Arab City Centers" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020607

APA StyleShehata, A. M. (2022). Current Trends in Urban Heritage Conservation: Medieval Historic Arab City Centers. Sustainability, 14(2), 607. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020607