Era of Molecular Diagnostics Techniques before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Molecular Diagnostics before Emergence of COVID-19

1.1. Timeline and History of Molecular Diagnosis—From Hippocrates to NGS

1.1.1. The Invention of PCR

1.1.2. The Era of Next-Generation Sequencing

1.2. Some Molecular Diagnostic Tools Used in Clinical Laboratory before COVID-19

2. Advances in Molecular Diagnostic Tool after Emergence of COVID-19

2.1. Advances in Molecular Diagnostic Techniques in COVID-19

2.1.1. Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP)

2.1.2. Biosensors

Field-Effect Transistors (FET)

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) Sensor

Cell-Based Potentiometric Biosensor

2.1.3. CRISPR-Based Diagnostics—SHERLOCK and DETECTR

SARS-CoV-2 DETECTR

Specific High Sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter UnLOCKing (SHERLOCK)

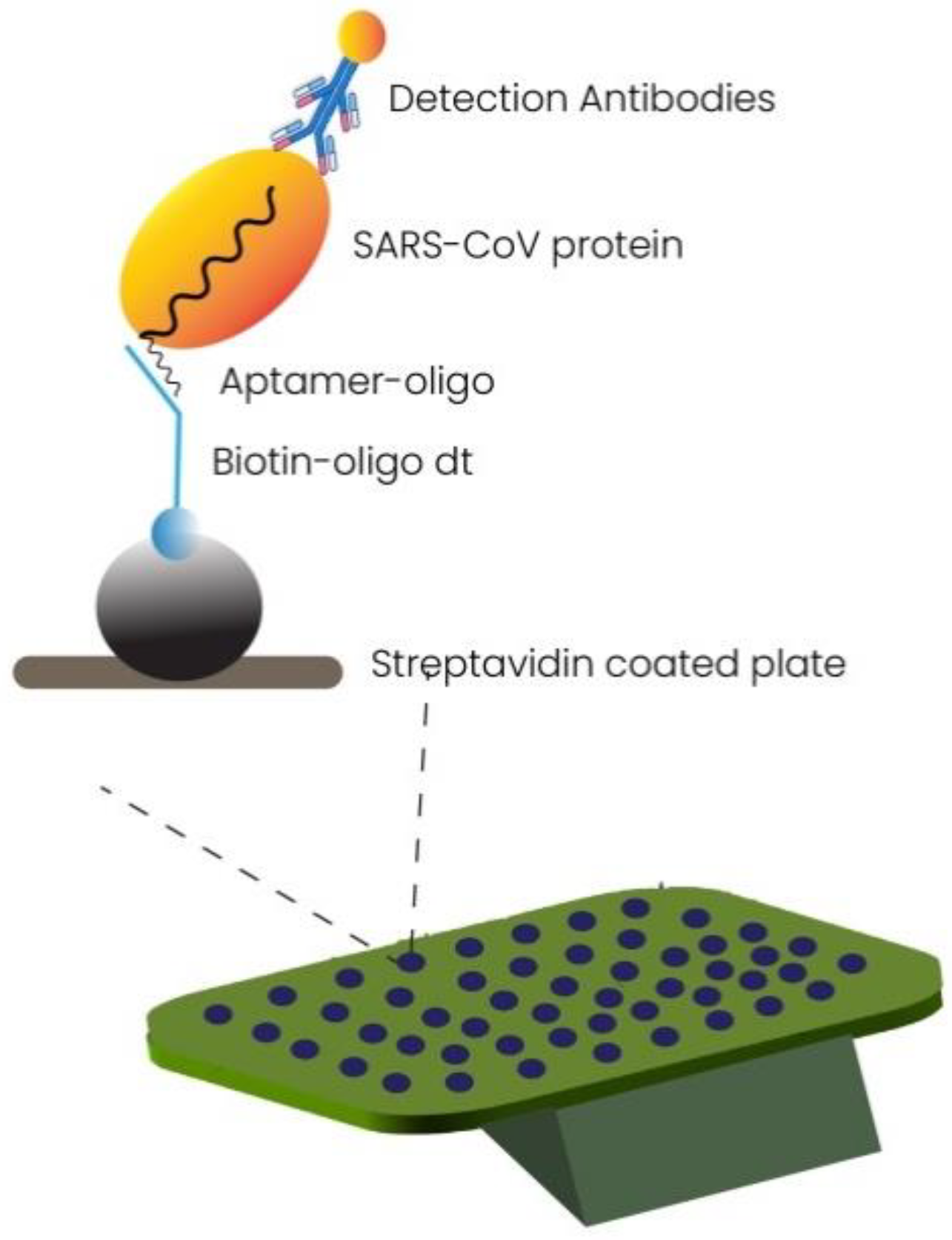

2.1.4. Aptamer-Based Diagnostics

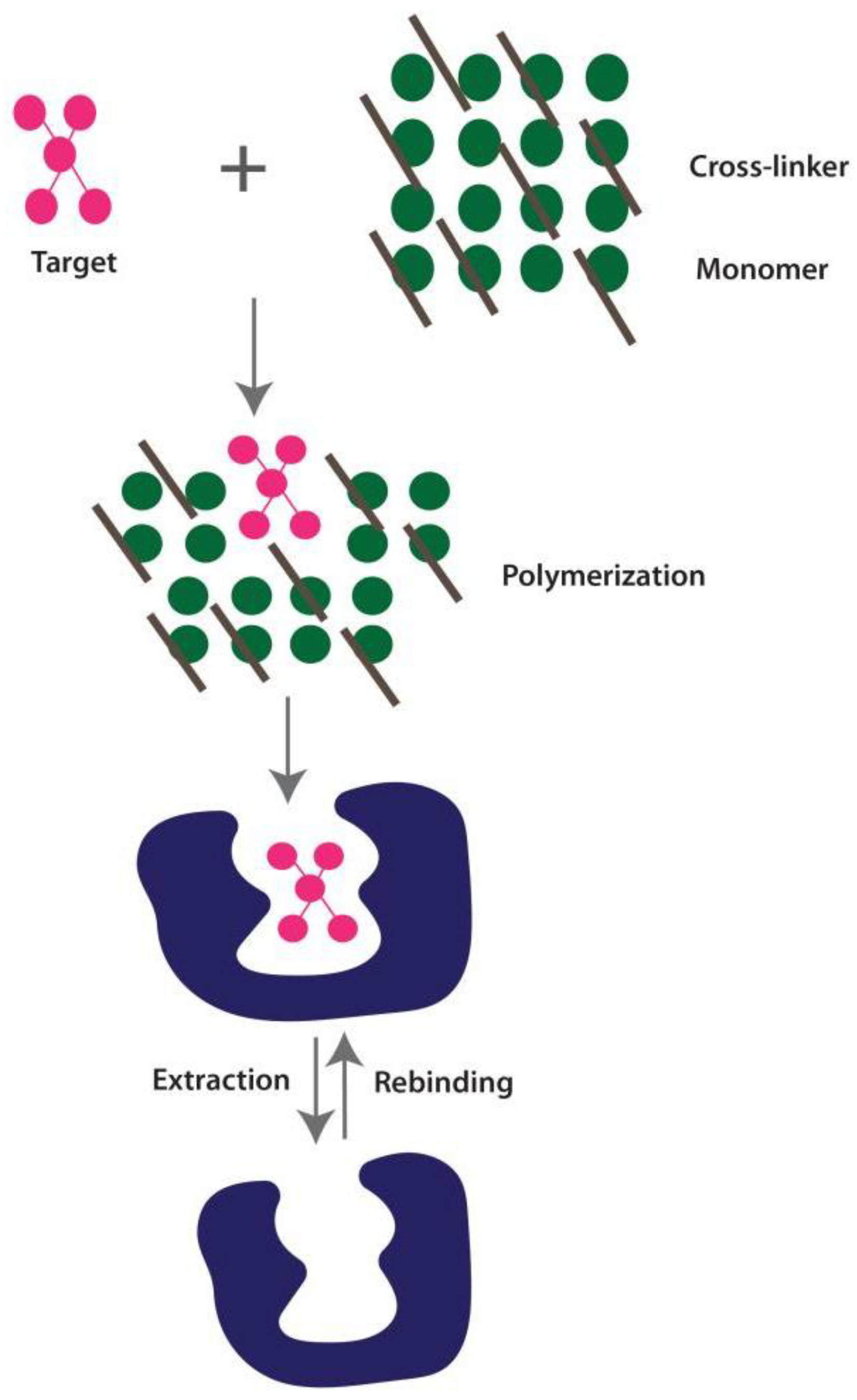

2.1.5. Molecular Imprinting Technology (MIT)-Based Diagnosis

2.1.6. Microarray-Based Diagnosis

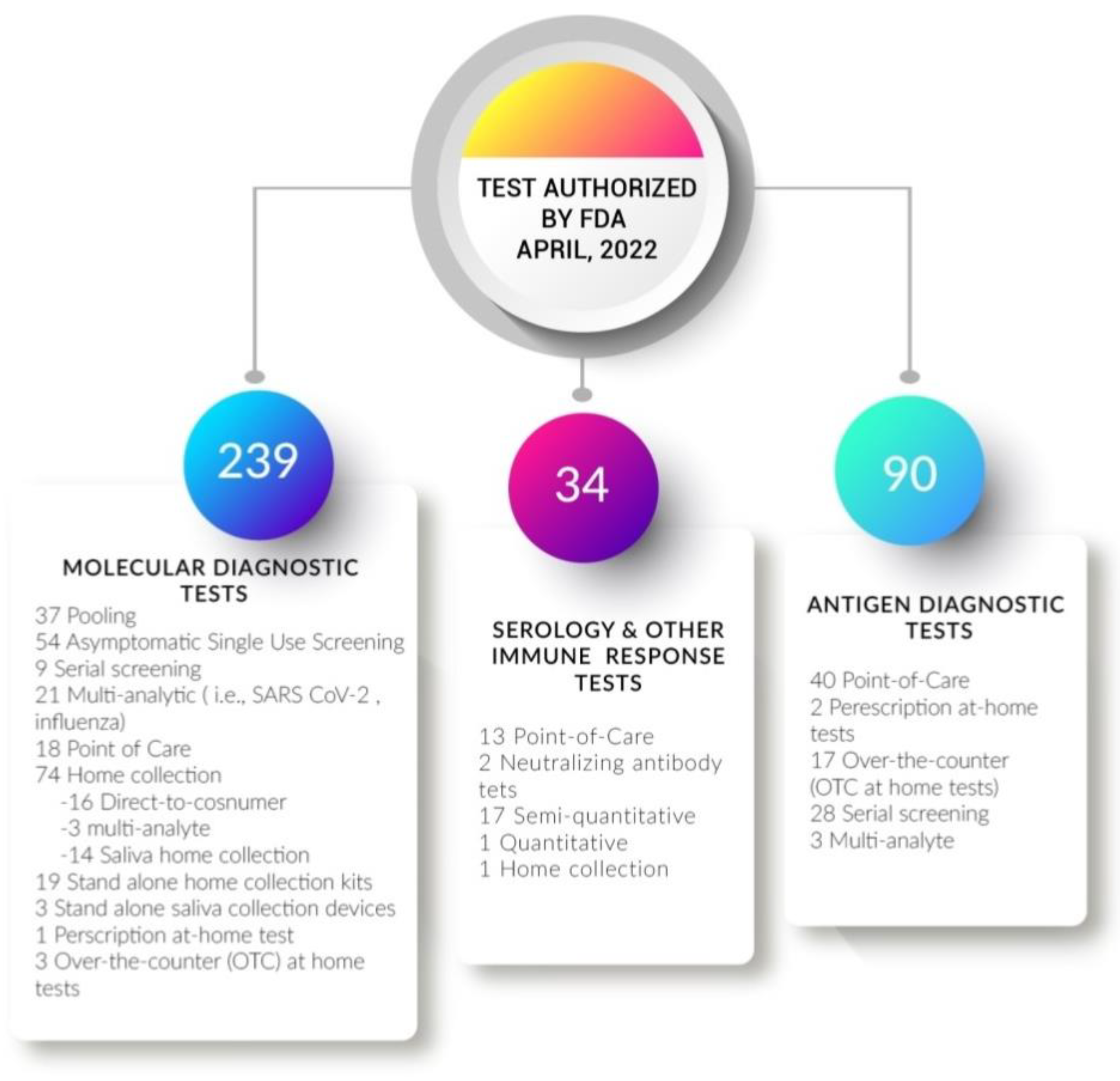

2.2. Development of New Kits for SARS-CoV-19 Detection

2.3. Point-of-Care Diagnostics

2.3.1. Molecular Detection-Based Point-Of-Care Devices

2.3.2. Antigen Detection-Based Point-of-Care Devices

2.3.3. Antibody Detection-Based Point-of Care Diagnostics

3. Future of Molecular Techniques

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| HSV | Herpes simplex virus |

| FISH | Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization |

| ZMWs | Zero-mode wave guides |

| SMRT | Single-molecule real-time sequencing |

| cPAS | Combinatorial Probe-Anchor Synthesis |

| RCR | Rolling Circular Replication |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| NDV | New Castle Disease Virus |

| RT-LAMP | Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification |

| LAMP | Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| FET | Field-Effect Transistors |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon resonance |

| PDMS | polydimethylsiloxane |

| FO-SPR | Fiber Optic Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| RPA | Recombinase Polymerase Amplification |

| RBD | Receptor binding domain |

| SENSOR | sensitive splint-based one-pot isothermal RNA detection |

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| MIT | Molecular imprinting technology |

| POC | Point-of-care |

References

- Coleman, W.B.; Tsongalis, G.J. Molecular Diagnostics: For the Clinical Laboratorian; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz, A.A.; Karaca, E.; Demkow, U.; Toruner, G.; Schoumans, J.; Cogulu, O. Evolution of genetic techniques: Past, present, and beyond. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 461524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, J. A pedagogy of sight: Microscopic vision in Robert Hooke’s Micrographia. Q. J. Speech 2009, 95, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinkšel, M.; Writzl, K.; Maver, A.; Peterlin, B. Improving diagnostics of rare genetic diseases with NGS approaches. J. Community Genet. 2021, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacenza, N.; Pasqualini, T.; Gottlieb, S.; Knoblovits, P.; Costanzo, P.R.; Stewart Usher, J.; Rey, R.A.; Martínez, M.P.; Aszpis, S. Clinical presentation of Klinefelter’s syndrome: Differences according to age. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 2012, 324835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.; Stirling, D. A short history of the polymerase chain reaction. In PCR Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fakruddin, M.; Chowdhury, A. Pyrosequencing an alternative to traditional Sanger sequencing. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 8, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Birbian, N.; Sinha, S.; Goswami, A. A critical review on PCR, its types and applications. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 2014, 1, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfs, A.; Schuller, I.; Finckh, U.; Weber-Rolfs, I. PCR: Clinical Diagnostics and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Hu, N.; Wang, B.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; He, Y.; Lin, D. A brief utilization report on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer. Mycology 2011, 2, 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.; Nielsen, P.H.; Andreasen, K.H.; Juretschko, S.; Nielsen, J.L.; Schleifer, K.-H.; Wagner, M. Combination of fluorescent in situ hybridization and microautoradiography—A new tool for structure-function analyses in microbial ecology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulski, J.K. Next-generation sequencing—An overview of the history, tools, and “Omic” applications. In Next Generation Sequencing-Advances, Applications and Challenges; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2016; Volume 10, p. 61964. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Shin, S.Y.; Kim, K.; Park, K.; Shin, S.; Ihm, C. Determining genotypic drug resistance by Ion semiconductor sequencing with the Ion AmpliSeq™ TB panel in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Ann. Lab. Med. 2018, 38, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardui, S.; Ameur, A.; Vermeesch, J.R.; Hestand, M.S. Single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing comes of age: Applications and utilities for medical diagnostics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeck, W.R.; Reinhardt, J.A.; Baltrus, D.A.; Hickenbotham, M.T.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Dangl, J.L.; Jones, C.D. Extending assembly of short DNA sequences to handle error. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2942–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y. Recent patents and advances in the next-generation sequencing technologies. Recent Pat. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 1, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Metwally, S.; Ouda, O.M.; Helmy, M. First-and next-generations sequencing methods. In Next Generation Sequencing Technologies and Challenges in Sequence Assembly; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Oever, J.M.; Balkassmi, S.; Verweij, E.J.; van Iterson, M.; van Scheltema, P.N.A.; Oepkes, D.; van Lith, J.M.; Hoffer, M.J.; den Dunnen, J.T.; Bakker, E. Single molecule sequencing of free DNA from maternal plasma for noninvasive trisomy 21 detection. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehab, F.F. Molecular diagnostics: Past, present, and future. Hum. Mutat. 1993, 2, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demidov, V.V. DNA Diagnostics in the Fifty-Year Retrospect; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2003; pp. 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kresge, N.; Simoni, R.D.; Hill, R.L. Arthur Kornberg’s discovery of DNA polymerase I. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, e46–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, E. Technical review: In situ hybridization. Anat. Rec. 2014, 297, 1349–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Felice, F.; Micheli, G.; Camilloni, G. Restriction enzymes and their use in molecular biology: An overview. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edberg, S. Principles of nucleic acid hybridization and comparison with monoclonal antibody technology for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1985, 58, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxam, A.M.; Gilbert, W. [57] Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1980; pp. 499–560. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinos, G.P.; Ansorge, W.J. Molecular diagnostics: Past, present, and future. In Molecular Diagnostics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Saiki, R.K.; Scharf, S.; Faloona, F.; Mullis, K.B.; Horn, G.T.; Erlich, H.A.; Arnheim, N. Enzymatic amplification of β-globin genomic sequences and restriction site analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science 1985, 230, 1350–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, I.M.; Arden, K.E.; Nitsche, A. Real-time PCR in virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, E.; Ronaghi, M. Pyrosequencing. Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Psychesystems The History and Evolution of Molecular Diagnostics. 2020. Available online: https://psychesystems.com (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Stranneheim, H.; Lundeberg, J. Stepping stones in DNA sequencing. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 7, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzer, S.; Malde, K.; Lanzén, A.; Sharma, A.; Jonassen, I. Characteristics of 454 pyrosequencing data—Enabling realistic simulation with flowsim. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, i420–i425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sage, L. Faster, Cheaper DNA Sequencing; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, A.L. Probing the viromic frontiers. mBio 2015, 6, e01767-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.-C.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Li, X.; Lin, Q.; Kwong, S.; Liang, C. DNA sequencing technologies: Sequencing data protocols and bioinformatics tools. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.R. The year of sequencing: In 2007, the next-generation sequencing technologies have come into their own with an impressive array of successful applications. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, N.; He, Y.; Pong, R.; Lin, D.; Lu, L.; Law, M. Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems. J Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 251364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, W.; Xiong, X.; Meng, F.; Cui, X. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in potato by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 1473–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Olsen, H.E.; Paten, B.; Akeson, M. The Oxford Nanopore MinION: Delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, J.; Kim, J.; Han, H. Simple Molecular Diagnostic Tools in Clinical Medicine. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 6, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, M.; Walter, J.-G.; Stahl, F. Aptamer microarrays—Current status and future prospects. Microarrays 2015, 4, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spengler, B. Mass spectrometry imaging of biomolecular information. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminian, A.; Safari, S.; Razeghian-Jahromi, A.; Ghorbani, M.; Delaney, C.P. COVID-19 outbreak and surgical practice: Unexpected fatality in perioperative period. Ann. Surg. 2020, 272, e27–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, T.; Hands, R.E.; Bustin, S.A. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1559–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, M.A.; Geletkanycz, M.A.; Sanders, W.G. Upper echelons research revisited: Antecedents, elements, and consequences of top management team composition. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 749–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Orihara, Y.; Kawamura, R.; Imai, K.; Sakai, J.; Tarumoto, N.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, S.; Maesaki, S.; Maeda, T. Evaluation of rapid diagnosis of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 129, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Wu, X.; Wan, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhang, C. A novel reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification method for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Han, L.; Chen, T.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Li, S.; He, L.; Fu, X.; Chen, S. Multiplex reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification combined with nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensor for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 166, 112437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, J.; Al-Maskri, A.A.A.; Kang, Y.; Zeng, S.; Cai, S. Recent advances and perspectives of nucleic acid detection for coronavirus. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 10, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Nogués, M.; Gil, F.; Mas-Moruno, C. Antimicrobial peptides: Powerful biorecognition elements to detect bacteria in biosensing technologies. Molecules 2018, 23, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrikou, S.; Moschopoulou, G.; Tsekouras, V.; Kintzios, S. Development of a portable, ultra-rapid and ultra-sensitive cell-based biosensor for the direct detection of the SARS-CoV-2 S1 spike protein antigen. Sensors 2020, 20, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishee, M.J.; Ali, T.; Jahan, N.; Khandker, S.S.; Haq, M.A.; Khondoker, M.U.; Sil, B.K.; Lugova, H.; Krishnapillai, A.; Abubakar, A.R. COVID-19 pandemic: Review of contemporary and forthcoming detection tools. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, G.; Lee, G.; Kim, M.J.; Baek, S.-H.; Choi, M.; Ku, K.B.; Lee, C.-S.; Jun, S.; Park, D.; Kim, H.G. Rapid detection of COVID-19 causative virus (SARS-CoV-2) in human nasopharyngeal swab specimens using field-effect transistor-based biosensor. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 5135–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.; Chouhan, R.S.; Shahdeo, D.; Shrikrishna, N.S.; Kesarwani, V.; Horvat, M.; Gandhi, S. A Recent Update on Advanced Molecular Diagnostic Techniques for COVID-19 Pandemic: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 732756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petryayeva, E.; Krull, U.J. Localized surface plasmon resonance: Nanostructures, bioassays and biosensing—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 706, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhzadeh, E.; Eissa, S.; Ismail, A.; Zourob, M. Diagnostic techniques for COVID-19 and new developments. Talanta 2020, 220, 121392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, D.; Bhatia, H.; Sai, V.; Satija, J. P-FAB: A fiber-optic biosensor device for rapid detection of COVID-19. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2020, 5, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygun, Z.O.; Yeniay, L.; Sağın, F.G. CRISPR-dCas9 powered impedimetric biosensor for label-free detection of circulating tumor DNAs. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1121, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broughton, J.; Deng, X.; Yu, G.; Fasching, C.; Servellita, V.; Singh, J.; Zorn, K. CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yin, K.; Li, Z.; Liu, C. All-in-One dual CRISPR-cas12a (AIOD-CRISPR) assay: A case for rapid, ultrasensitive and visual detection of novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and HIV virus. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.; Phutela, R.; Ansari, A.H.; Sinha, D.; Sharma, N.; Kumar, M.; Aich, M.; Sharma, S.; Rauthan, R.; Singhal, K.; et al. Rapid, field-deployable nucleobase detection and identification using FnCas9. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Lee, J.W.; Essletzbichler, P.; Dy, A.J.; Joung, J.; Verdine, V.; Donghia, N.; Daringer, N.M.; Freije, C.A. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 2017, 356, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, M.J.; Koob, J.G.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Zhang, F. SHERLOCK: Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR nucleases. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 2986–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, M.I.; Makhawi, A.M. SHERLOCK and DETECTR: CRISPR-Cas systems as potential rapid diagnostic tools for emerging infectious diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e00745-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Wu, J.; Gu, J.; Shen, L.; Mao, L. Application of aptamers in virus detection and antiviral therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, N.J. Animal communication: When I’m calling you, will you answer too? Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R713–R715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Ni, X.; Dai, J. A DNA aptamer based method for detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, C.H.; Jang, S.; Shin, G.; Jung, G.Y.; Lee, J.W. Sensitive fluorescence detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in clinical samples via one-pot isothermal ligation and transcription. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, D.-G.; Jeon, I.-J.; Kim, J.D.; Song, M.-S.; Han, S.-R.; Lee, S.-W.; Jung, H.; Oh, J.-W. RNA aptamer-based sensitive detection of SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Analyst 2009, 134, 1896–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.U.; Iqbal, J. An update on molecular diagnostics for COVID-19. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 560616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uygun, Z.O.; Uygun, H.D.E.; Ermiş, N.; Canbay, E. Molecularly imprinted sensors—New sensing technologies. In Biosensors–Micro and Nanoscale Applications; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2015; pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Raziq, A.; Kidakova, A.; Boroznjak, R.; Reut, J.; Öpik, A.; Syritski, V. Development of a portable MIP-based electrochemical sensor for detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 178, 113029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandy Chatterjee, T.; Bandyopadhyay, R. A molecularly imprinted polymer-based technology for rapid testing of COVID-19. Trans. Indian Natl. Acad. Eng. 2020, 5, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, O.I.; Dattilo, M.; Patitucci, F.; Malivindi, R.; Pezzi, V.; Perrotta, I.; Ruffo, M.; Amone, F.; Puoci, F. “Monoclonal-type” plastic antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 based on Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. BioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Hou, X.; Liang, T.; Wang, D.; Teng, F.; Dai, J.; Duan, H.; Guo, S. SARS-CoV-2 proteome microarray for mapping COVID-19 antibody interactions at amino acid resolution. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 2238–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makatsa, M.S.; Tincho, M.B.; Wendoh, J.M.; Ismail, S.D.; Nesamari, R.; Pera, F.; De Beer, S.; David, A.; Jugwanth, S.; Gededzha, M.P. SARS-CoV-2 antigens expressed in plants detect antibody responses in COVID-19 patients. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Assis, R.R.; Jain, A.; Nakajima, R.; Jasinskas, A.; Felgner, J.; Obiero, J.M.; Norris, P.J.; Stone, M.; Simmons, G.; Bagri, A. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in COVID-19 convalescent blood using a coronavirus antigen microarray. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Deng, Z.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Q.; Hu, Y.-Q. Comprehensive detection and identification of seven animal coronaviruses and human respiratory coronavirus 229E with a microarray hybridization assay. Intervirology 2010, 53, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, C. COVID-19 spurs wave of innovative diagnostics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.N.; McCarthy, C.; Lantigua, D.; Camci-Unal, G. Development of diagnostic tests for detection of SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA List of COVID-19 Test Kits with FDA Special Certification and Performance Validation Conducted and/or Recommended by the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine (RITM). 2021 FDA Advisory No.2021–2094. Available online: https://www.fda.gov.ph/fda-advisory-no-2021-2094-list-of-covid-19-test-kits-with-fda-special-certification-and-performance-validation-conducted-and-or-recommended-by-the-research-institute-for-tropical-medicine-ritm/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- FDA. FDA Updates. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cliac/docs/april-2022/3_fda-update.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Valera, E.; Jankelow, A.; Lim, J.; Kindratenko, V.; Ganguli, A.; White, K.; Kumar, J.; Bashir, R. COVID-19 point-of-care diagnostics: Present and future. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 7899–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, A.; Mostafa, A.; Berger, J.; Aydin, M.Y.; Sun, F.; de Ramirez, S.A.S.; Valera, E.; Cunningham, B.T.; King, W.P.; Bashir, R. Rapid isothermal amplification and portable detection system for SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22727–22735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguli, A.; Mostafa, A.; Berger, J.; de Ramirez, S.S.; Baltaji, A.; Roth, K.; Aamir, M.; Aedma, S.; Mady, M.; Mahajan, P. RT-LAMP assay for ultra-sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva and VTM clinical samples. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, L. Lucira Check It. 2021. Available online: https://www.lucirahealth.com/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Health, C. Cue Health Leading the fight against COVID-19. 2022. Available online: https://www.cuehealth.com/products/how-cue-detects-covid-19/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Visby Medical COVID-19 Point of Care Test. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/145914/download (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Prince-Guerra, J.L.; Almendares, O.; Nolen, L.D.; Gunn, J.K.; Dale, A.P.; Buono, S.A.; Deutsch-Feldman, M.; Suppiah, S.; Hao, L.; Zeng, Y. Evaluation of Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 infection at two community-based testing sites—Pima County, Arizona, November 3–17, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojsoska, B.; Larsen, S.; Olsen, D.A.; Madsen, J.S.; Brandslund, I.; Alatraktchi, F.A. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 detection using electrochemical immunosensor. Sensors 2021, 21, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Event/Invention | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Categorization of sickle cell anemia as a molecular disease | [19] |

| 1957 | Phosphonate synthesis assay for small oligodeoxynucleotides | [20] |

| 1958 | Isolation of DNA Polymerases by Arthur Kornberg | [21] |

| 1960 | Initial hybridization methods and electrochemical DNA Detection by Roy Britten | [20] |

| 1965 | Solid-phase oligodeoxynucleotide synthesis and Enzymatic synthesis of short RNAs | [20] |

| 1969 | Development of In situ hybridization technique by Gall and Pardue | [22] |

| 1970 | Isolation the first restriction enzyme and reverse transcriptase by Hamilton Smith | [23] |

| 1970 | Development of Nucleic acid hybridization methods | [24] |

| 1975 | Development of Southern blotting Technique | [20] |

| 1977 | Development of First Generation Sequencing technique-Sanger sequencing | [25] |

| 1980 | Maxim Gilbert Sequencing method | [26] |

| 1985 | Establishment of Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (RFLP) | [27] |

| 1985 | Invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) | [9] |

| 1985 | Development of technique for detecting patient’s beta-globin gene for the diagnosis of sickle cell anemia | [28] |

| 1986 | Development of Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) | [27] |

| 1988 | Discovery of the first thermostable DNA polymerase | [27] |

| 1988–1991 | Invention of first DNA Chip conceptions | [20] |

| 1991 | Designing of DNA/RNA mimics: peptide nucleic acid probes/PNA openers Ligase chain reaction; thermophilic DNA ligases | [20] |

| 1992 | Conception of real time PCR | [29] |

| 1992 | Assays for whole genome amplification and Strand-displacement amplification | [20] |

| 1992 | Development of Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) | [27] |

| 1993 | Discovery of endonucleases for invasive cleavage assays | [27] |

| 1994 | Invention of DNA topological labeling | [20] |

| 1995 | Innovation of rolling amplification of circular probes | [20] |

| 1996 | First application of DNA microarrays | [27] |

| 1996 | Pyrosequencing technique-The next generation sequencing | [30] |

| 1998 | Lab-on-a-ChiP(microfluidics) for DNA analysis | [20] |

| 1985–1999 | Development of Immunoassays (Elisa, Western Blot, Immunostaining) | [20] |

| 2000 | Development of Massively parallel sequencing (MPS) by Lynx Therapeutics | [2] |

| 2001 | Application of protein profiling assays in diagnosis of human diseases | [27] |

| 2002 | HapMap project | [27] |

| 2002 | Development of Ion semiconductor sequencing | [31] |

| 2005 | Invention of Single molecule real time sequencing by Pacific Biosciences (SMRT) | [32] |

| 2005 | Invention of 454 Pyrosequencer system | [33] |

| 2005 | Invention of Polony sequencing by George M. Church | [34] |

| 2005 | Development of qRT-PCR, Virus microarrays | [35] |

| 2006 | Invention of Illumina/Solexa | [36] |

| 2007 | Invention of ABI/SoLID sequencing | [37,38] |

| 2013 | Invention of the CRISPR system | [39] |

| 2014 | Development of Portable oxford nanopore sequencing device | [40] |

| 2015 | Development of VirCapSeq-VERT | [35] |

| Device Name | Platform | Sample Used | Developer | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARMEN-Cas13a (Combinatorial Arrayed Reactions For Multiplexed Evaluation of Nucleic Acids) |

|

| Broad Institute, Harvard University | Considered for 169 human viruses |

| CRISPR-ChiP | gFET connected with a portable digital reader |

| Cardea Bio |

|

| CRISPR-Cas based Electrochemical microfluidic sensors |

|

| University of Freiburg, Germany |

|

| Convat optical biosensor | A portable 25 × 15 × 25 cm box device controlled via tablet |

| Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (Spain) |

|

| COVID-19 biosensor | Change in electrical resistance |

| University of Utah |

|

| Dual functional plasmonic photothermal biosensor (PPT) | Glass surface associated with gold nanoislands Functionalized with cDNA sequences |

| Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich |

|

| FET Biosensors | gFET linked to a semiconductor analyzer |

| Korea Basic Science Institute |

|

| Femto Spot COVID-19 Rapid Diagnostic Test | Change in conductivity |

| Nano DiagnosiX |

|

| One-step COVID-19 test |

|

| Northwestern University, Stemloop |

|

| VIRRION (virus capture with rapid Raman spectroscopy detection and identification) | ChiP consisting of N-doped C nanotube arrays with gold nanoparticles for increasing Raman spectroscopic signals |

| Pennsylvania State University |

|

| Kit Name | Developer | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of Permitted PCR Based Test Kits for Commercial Use | ||||

| 1 | SARS-CoV-2 Fluorescent PCR Kit | Maccura Biotechnology Co., Ltd. | 96.23% | 100% |

| 2 | BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1) | BioFire Diagnostic, LCC. | 100% | 100% |

| 3 | DENSY PACK UNIVERSAL REAGENT (i-DENSY PACK UNIVERSAL SARS-CoV-2 DETECTION SYSTEM) | ARKRAY INDUSTRY INC. | 100% | 100% |

| 4 | SARS-CoV-2 DETECTION PRIMER PROBE SET REAGENT (i-DENSY PACK UNIVERSAL SARS-CoV-2 DETECTION SYSTEM) | ARKRAY INDUSTRY INC. | 100% | 100% |

| 5 | SARS-COV-2 Nucleic Acid Detection Kit (PCR-Fluorescent Probe Method) | Zybio Inc. | 100% | 100% |

| 6 | Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 | Macare Medicals, Inc | 100% | 99% |

| List of Permitted Antigen Test Kits for Commercial Use | ||||

| 1 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbot Rapid Diagnostics Jena GmbH | CT < 30 (97.83%) | 100% |

| 2 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbot Diagnostics Korea Inc | CT < 30 (97.83%) | 100% |

| 3 | SOFIA 2 SARS Antigen FIA | Quidel Corporation | CT < 30 (92.86%) | 100% |

| 4 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Rapid Diagnostics | CT < 30 (97.83%) | 100% |

| 5 | STANDARD™ Q COVID-19 Ag TEST KIT | SD Biosensor, Inc | CT < 30 93.1% | 100% |

| 6 | PanbioTM COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device | Abbott Rapid Diagnostics | CT < 30 (90.5%) | 100% |

| 7 | NowCheck COVID-19 Antigen Test | BioNote Inc-22 | CT < 30 (91.4%) | 100% |

| 8 | Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Antigen Detection Kit (Colloidal Gold Method)//Wondfo2019-nCoV Antigen Test (Lateral flow) | Guangzhou Wondfo Biotech Co., | CT < 30 (92.2%) | 100% |

| List of Permitted Antibody Rapid Test Kits for Commercial Use | ||||

| 1 | NADAL COVID-19 IgG/IgM Test | Nal Von Minden GmbH- Carl-Zeiss-Str. 12, 47,445 Moers, Germany | 92.67% | 100% |

| 2 | VivaDiagTM COVID-19 IgM/IgG Rapid Test | Vivachek Biotech Hangzhou Co. Ltd. | 92.00% | 99.33% |

| Kit Name | Principle | Approved |

|---|---|---|

| Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2/Flu/RSV | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 DoD | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| Accula SARS-CoV-2 Test (Mesa Biotech Inc.) | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| Cobas SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A/B Nucleic Acid Test (Roche Molecular Systems, Inc.) | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1-EZ (BioFire Diagnostics, LLC) | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| Visby Medical COVID-19 Point-of-Care Test (Visby Medical, Inc.). | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| Visby Medical test | RT-PCR | EUA-approved |

| ID NOW COVID-19 test | RT-LAMP | EUA-approved |

| Cue COVID-19 Test | RT-LAMP | EUA-approved |

| Kit Name | Principle | Approved |

|---|---|---|

| LumiraDx SARS-CoV-2 Ag Test(LumiraDx UK Ltd.) | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| CareStart COVID-19 Antigen test (Access Bio, Inc.) | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card (Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough,Inc.), | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| BD Veritor System for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Becton, Dickinson and Company, LLC) | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| BD Veritor System for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Becton, Dickinson and Company, LLC), | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| QuickVue SARS Antigen Test | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| Sofia 2 SARS Antigen FIA | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| Sofia 2 Flu + SARS Antigen FIA (all three from Quidel Corporation) | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| Status COVID-19/Flu (Princeton BioMeditech Corp.) | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| Ellume COVID-19 Home Test | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card Home Test | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| QuickVue At-Home OTC COVID-19 Test | Antigen detection | EUA-approved |

| Kit Name | Principle | Approved |

|---|---|---|

| Assure COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Device (Assure Tech.) | Antibody Detection | EUA-approved |

| RightSign COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette (Hangzhou Biotest Biotech) | Antibody Detection | EUA-approved |

| RapCov Rapid COVID-19 Test (Advaite, Inc.) | Antibody Detection | EUA-approved |

| MidaSpot COVID-19 Antibody Combo Detection Kit (Nirmidas Biotech, Inc.) | Antibody Detection | EUA-approved |

| Sienna-Clarity COVIBLOCK COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette (SalofaOy) | Antibody Detection | EUA-approved |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alamri, A.M.; Alkhilaiwi, F.A.; Ullah Khan, N. Era of Molecular Diagnostics Techniques before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 4769-4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44100325

Alamri AM, Alkhilaiwi FA, Ullah Khan N. Era of Molecular Diagnostics Techniques before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2022; 44(10):4769-4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44100325

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlamri, Ahmad M., Faris A. Alkhilaiwi, and Najeeb Ullah Khan. 2022. "Era of Molecular Diagnostics Techniques before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 44, no. 10: 4769-4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44100325

APA StyleAlamri, A. M., Alkhilaiwi, F. A., & Ullah Khan, N. (2022). Era of Molecular Diagnostics Techniques before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 44(10), 4769-4789. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb44100325