Characterization of a Cancer-Induced Bone Pain Model for Use as a Model of Cancer Cachexia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Animals

2.3. LLC Cell Inoculation

2.4. Dissections

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

2.6. Skeletal Muscle Histology

2.7. Grip Strength Test

2.8. Adipose Tissue Histology

2.9. Determinations of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α and Interleukin (IL)-6 Concentrations in Plasma

2.10. Forced Swim Test (FST)

2.11. Tail Suspension Test (TST)

2.12. Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) Test

2.13. Weight-Bearing Test

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

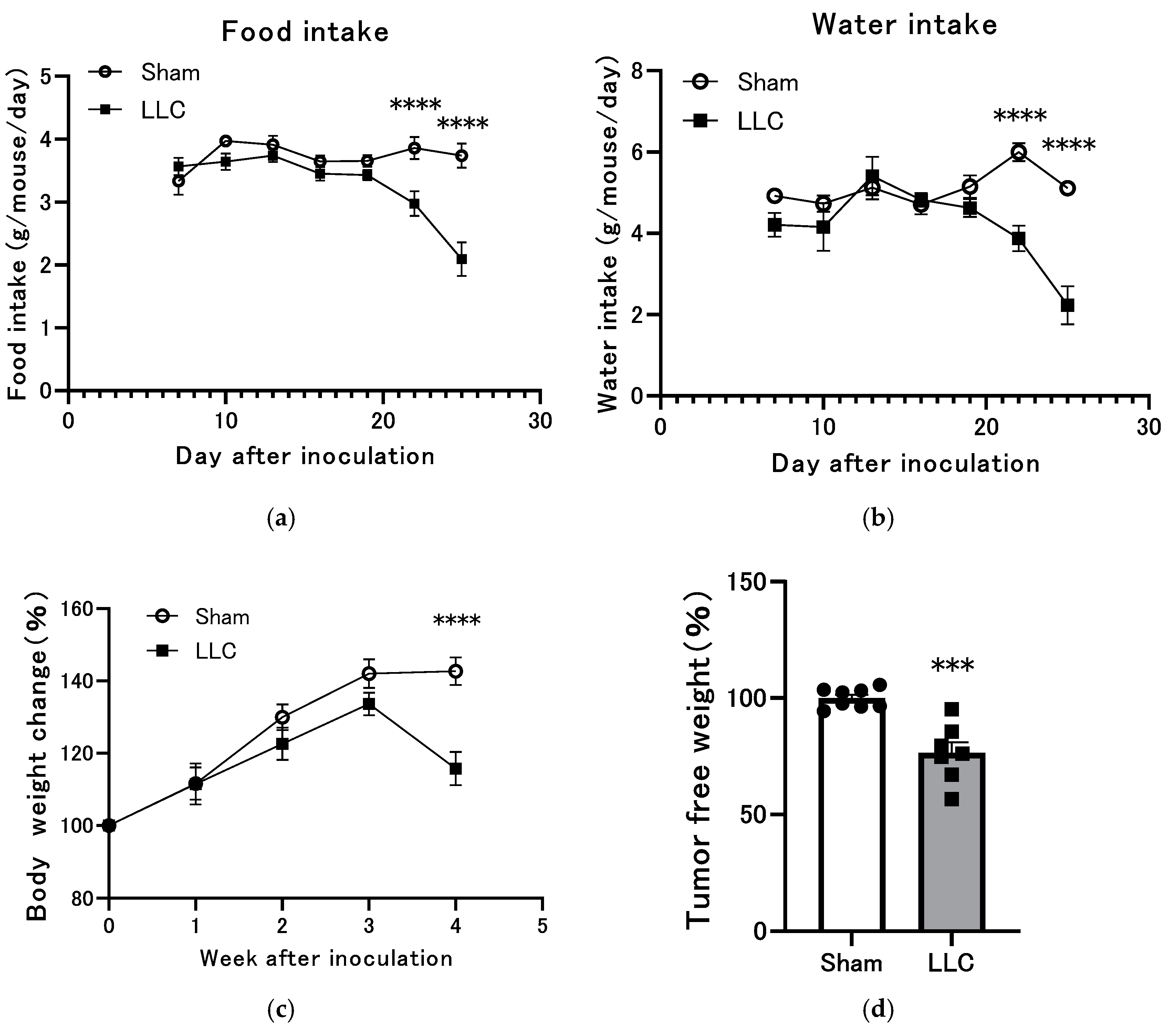

3.1. Changes in Body Weight, Food Intake, and Water Intake of Mice Implanted with LLC Tumors in the Femoral Intramedullary Space

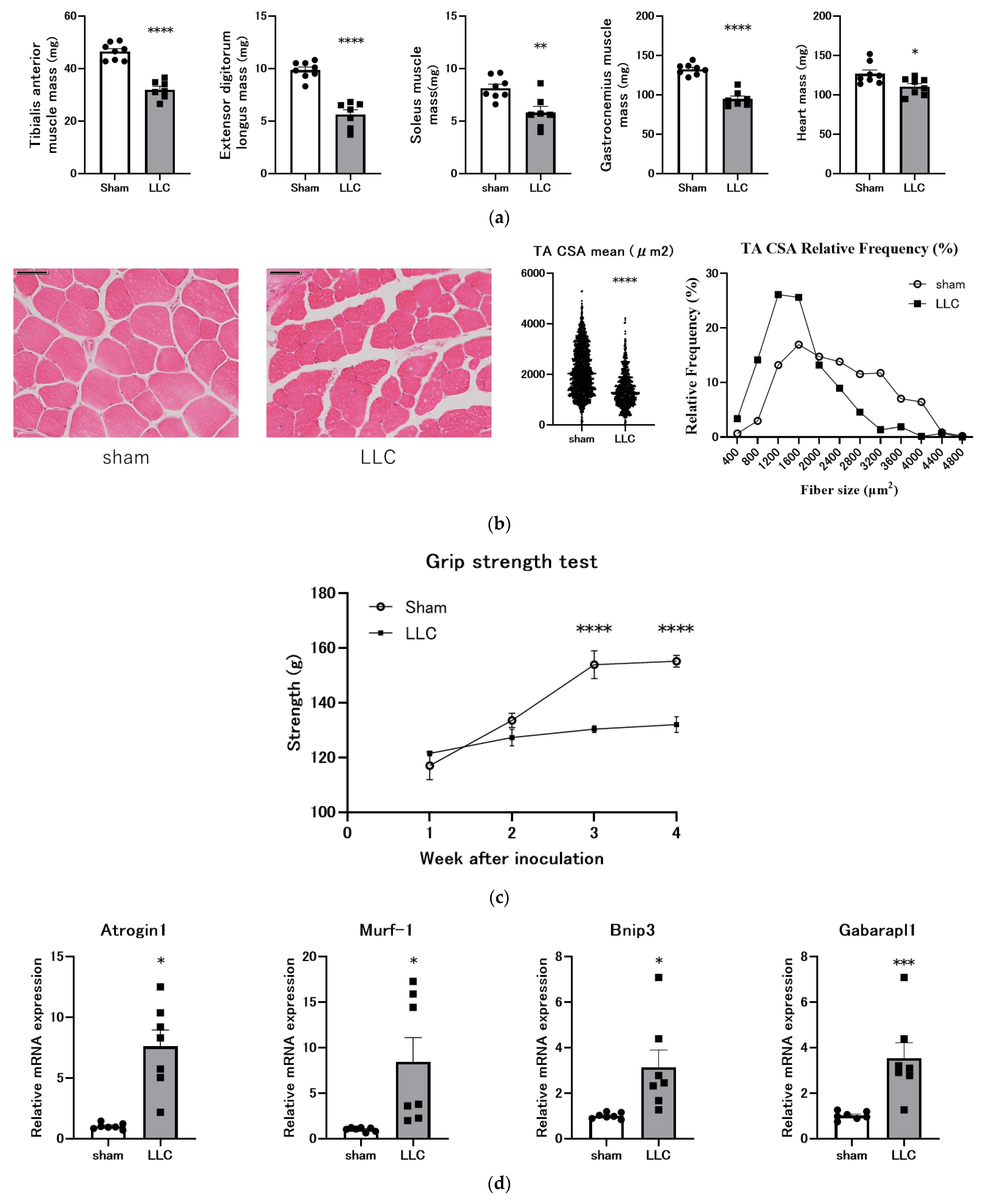

3.2. Femoral Implantation of LLC Cells Induces Progressive Skeletal Muscle Atrophy

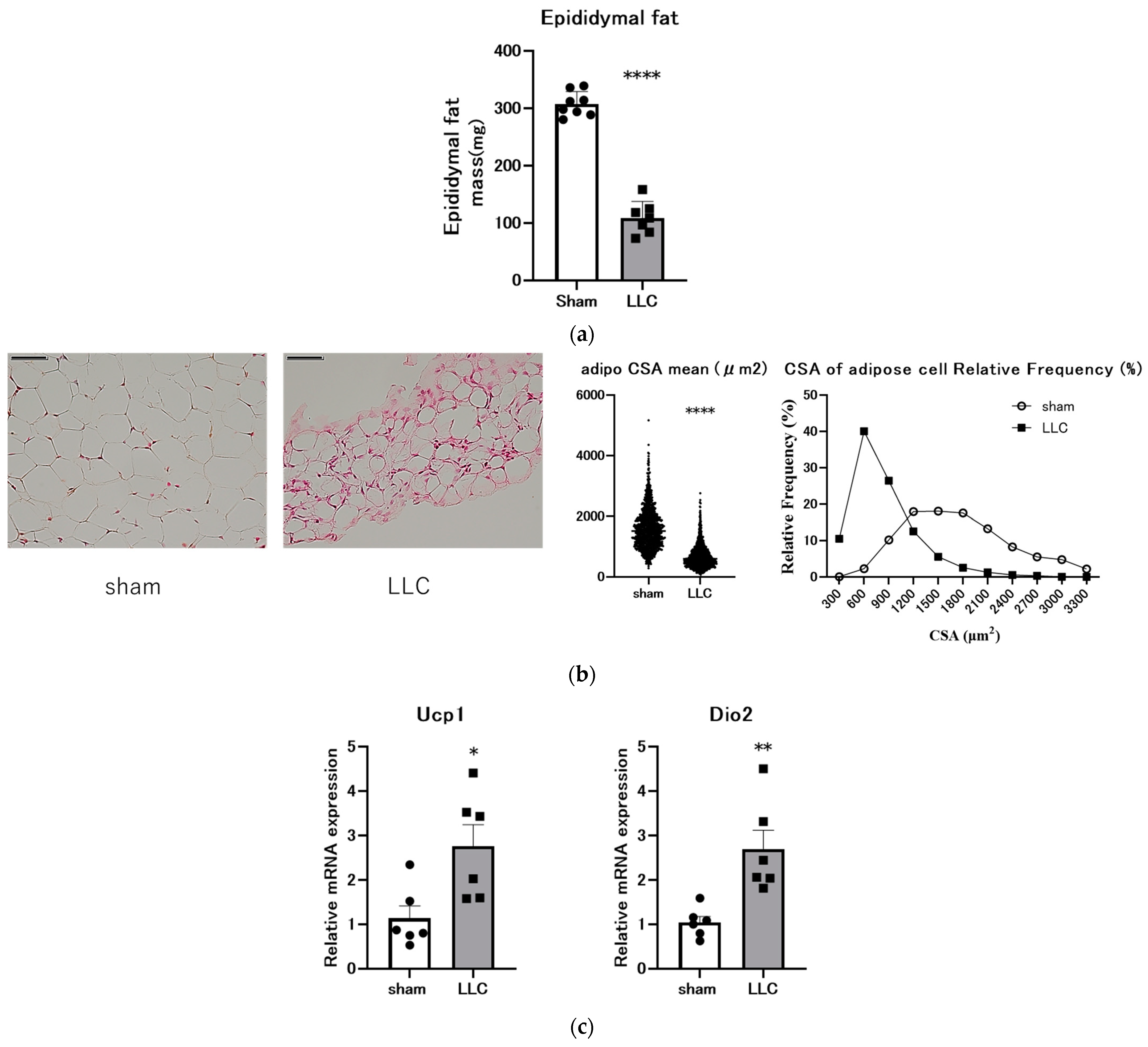

3.3. Femoral Implantation of LLC Cells Induces Adipose Tissue Loss

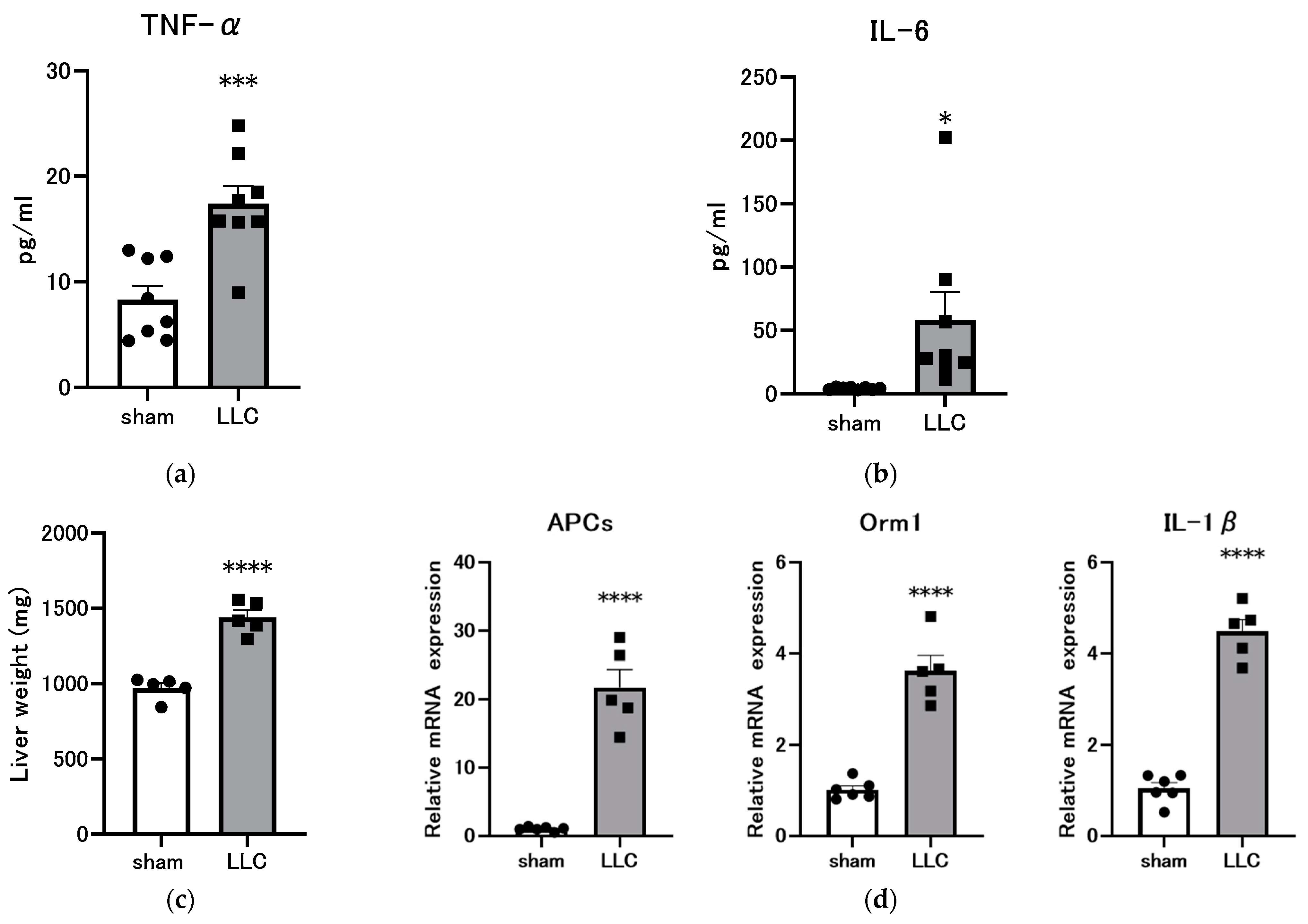

3.4. Femoral Implantation of LLC Induces a Systemic Inflammatory Response

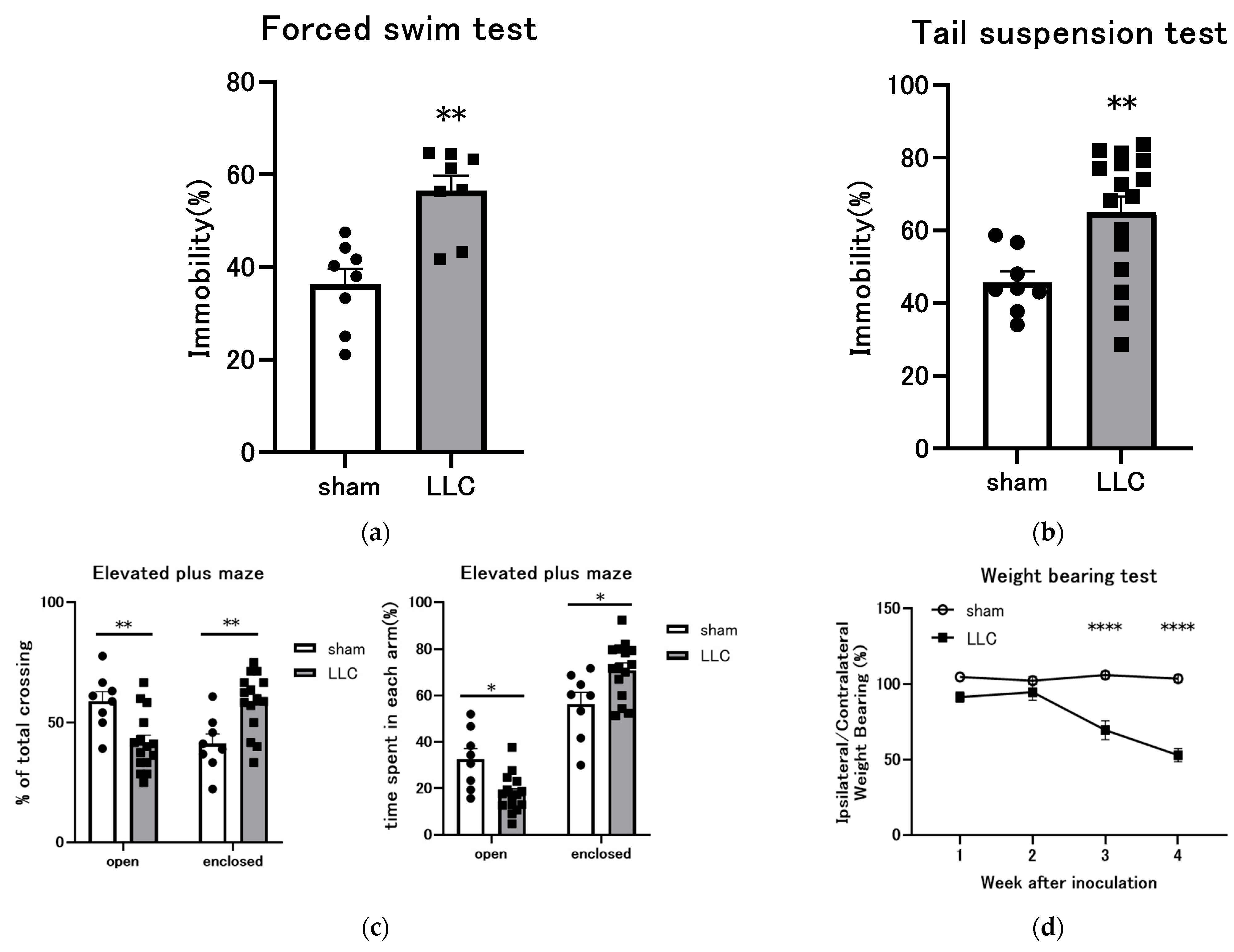

3.5. Behavioral Experiments Were Conducted on Mice with LLC Cells Implanted in the Femoral Bone Marrow Cavity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peixoto da Silva, S.; Santos, J.M.O.; Costa, E.; Silva, M.P.; da Costa, R.M.G.; Medeiros, R. Cancer cachexia and its pathophysiology: Links with sarcopenia, anorexia and asthenia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Zhang, L. Cancer Cachexia: Definition, Staging, and Emerging Treatments. CMAR 2020, 12, 5597–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Anthony, T.G.; Ayres, J.S.; Biffi, G.; Brown, J.C.; Caan, B.J.; Feliciano, E.M.; Coll, A.P.; Dunne, R.F.; Goncalves, M.D.; et al. Cachexia: A systemic consequence of progressive, unresolved disease. Cell 2023, 186, 1824–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrianthefs, P.M.; Batistaki, C. Cancer cachexia and immunomodulation. J. BUON 2005, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Brown, J.L.; Washington, T.A.; Greene, N.P. Development and Progression of Cancer Cachexia: Perspectives from Bench to Bedside. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2020, 2, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, S.H.R.; Previgliano, C.; Khandelwal, K.; Shi, R. Cachexia Index in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2015, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, T.; Sari, I.N.; Wijaya, Y.T.; Julianto, N.M.; Muhammad, J.A.; Lee, H.; Chae, J.H.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer Cachexia: Molecular Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.L. Cancer cachexia: Pathophysiology and association with cancer-related pain. Front. Pain Res. 2022, 3, 971295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, V.C.; Martin, P.; Lewandowski, P.A. Cancer cachexia: Impact, mechanisms and emerging treatments. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdale, M.J. Pathogenesis of cancer cachexia. J. Support. Oncol. 2003, 1, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shyh-Chang, N. Metabolic changes during cancer cachexia pathogenesis. In Translational Research in Breast Cancer: Biomarker Diagnosis, Targeted Therapies and Approaches to Precision Medicine; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Arends, J.; Strasser, F.; Gonella, S.; Solheim, T.S.; Madeddu, C.; Ravasco, P.; Buonaccorso, L.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Baldwin, C.; Chasen, M.; et al. Cancer cachexia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advani, S.M.; Advani, P.G.; VonVille, H.M.; Jafri, S.H. Pharmacological management of cachexia in adult cancer patients: A systematic review of clinical trials. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Bradley, L.; Del Fabbro, E. Updates in Cancer Cachexia: Clinical Management and Pharmacologic Interventions. Cancers 2024, 16, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakabayashi, H.; Arai, H.; Inui, A. The regulatory approval of anamorelin for treatment of cachexia in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, and colorectal cancer in Japan: Facts and numbers. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.; Katakami, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Atagi, S.; Yoshimori, K.; Kagamu, H.; Saito, H.; Takiguchi, Y.; Aoe, K.; Koyama, A.; et al. Anamorelin (ONO-7643) in Japanese patients with non-small cell lung cancer and cachexia: Results of a randomized phase 2 trial. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3495–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katakami, N.; Uchino, J.; Yokoyama, T.; Naito, T.; Kondo, M.; Yamada, K.; Kitajima, H.; Yoshimori, K.; Sato, K.; Saito, H.; et al. Anamorelin (ONO-7643) for the treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer and cachexia: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of Japanese patients (ONO-7643-04). Cancer 2017, 124, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicine Agency. Assessment Report–Aldumiz. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/adlumiz-epar-refusal-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Kojima, K.; Furukawa, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Inoue, S. First case report of anamorelin-induced fatal arrhythmia complicated by sinus arrest and refractory ventricular tachycardia. Heart Case Rep. 2023, 9, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamauchi, S.; Furuse, J.; Takano, T.; Munemoto, Y.; Furuya, K.; Baba, H.; Takeuchi, M.; Choda, Y.; Higashiguchi, T.; Naito, T.; et al. A multicenter, open-label, single-arm study of anamorelin (ONO-7643) in advanced gastrointestinal cancer patients with cancer cachexia. Cancer 2019, 125, 4294–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulino, P.; Berardi, E.; Cardillo, V.M.; Rizzuto, E.; Perniconi, B.; Ramina, C.; Padula, F.; Spugnini, E.P.; Baldi, A.; Faiola, F.; et al. Molecular, cellular and physiological characterization of the cancer cachexia-inducing C26 colon carcinoma in mouse. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthys, P.; Heremans, H.; Opdenakker, G.; Billiau, A. Anti-interferon-gamma antibody treatment, growth of Lewis lung tumours in mice and tumour-associated cachexia. Eur. J. Cancer 1991, 27, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voltarelli, F.A.; Frajacomo, F.T.; Padilha, C.d.S.; Testa, M.T.J.; Cella, P.S.; Ribeiro, D.F.; de Oliveira, D.X.; Veronez, L.C.; Bisson, G.S.; Moura, F.A.; et al. Syngeneic B16F10 Melanoma Causes Cachexia and Impaired Skeletal Muscle Strength and Locomotor Activity in Mice. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terawaki, K.; Sawada, Y.; Kashiwase, Y.; Hashimoto, H.; Yoshimura, M.; Suzuki, M.; Miyano, K.; Sudo, Y.; Shiraishi, S.; Higami, Y.; et al. New cancer cachexia rat model generated by implantation of a peritoneal dissemination-derived human stomach cancer cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 306, E373–E387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costelli, P.; Llovera, M.; Carbo, N.; Garcia-Martinez, C.; Lopez-Sorianoq, F.J.; Argiles, J.M. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) is unable to reverse cachexia in rats bearing an ascites hepatoma (Yoshida AH-130). Cancer Lett. 1995, 95, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltgalvis, K.A.; Berger, F.G.; Peña, M.M.; Mark Davis, J.; White, J.P.; Carson, J.A. Activity level, apoptosis, and development of cachexia in Apc(Min/+) mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coerver, K.A.; Woodruff, T.K.; Finegold, M.J.; Mather, J.; Bradley, A.; Matzuk, M.M. Activin signaling through activin receptor type II causes the cachexia-like symptoms in inhibin-deficient mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 1996, 10, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Talbert, E.E.; Cuitino, M.C.; Ladner, K.J.; Rajasekerea, P.V.; Siebert, M.; Shakya, R.; Leone, G.W.; Ostrowski, M.C.; Paleo, B.; Weisleder, N.; et al. Modeling Human Cancer-induced Cachexia. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, O.S.; Munro, A.J.; Tannock, I.F. Bone metastases: Pathophysiology and management policy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1991, 9, 509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini, M.; Ripamonti, C.; Beccaro, M.; Montella, M.; Borgia, P.; Casella, C.; Miccinesi, G. Prevalence, distress, management, and relief of pain during the last3 months of cancer patients’ life. Results of an Italian mortality follow-backsurvey. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M.H.J.; De Rijke, J.M.; Kessels, A.G.; Schouten, H.C.; Van Kleef, M.; Patijn, J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: Asystematic review of the past 40 years. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Moos, R.; Body, J.J.; Egerdie, B.; Stopeck, A.; Brown, J.; Fallowfield, I.; Patrick, D.L.; Cleeland, C.; Damyanov, D.; Palazzo, F.S.; et al. Pain and analgesic use associated with skeletal-related events in patients with advanced cancer and bone metastases. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 1327–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Huang, F.; Lin, M.; Chen, P.; Wan, H.; Gao, F.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, X. Transcriptomic Analysis of Long Noncoding RNA and mRNA Expression Profiles in the Amygdala of Rats with Bone Cancer Pain-Depression Comorbidity. Life 2021, 11, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Yu, G.; Wang, C. A Mouse Model of Cancer Induced Bone Pain: From Pain to Movement. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 873750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Nozato, S.; Inagaki, T.; Tsuchimochi, H.; Shirai, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Imaizumi, Y.; Hongyo, K.; Yokoyama, S.; et al. Modified forelimb grip strength test detects aging-associated physiological decline in skeletal muscle function in male mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, A.; Dao, D.T.; Arad, M.; Terrillion, C.E.; Piantadosi, S.C.; Gould, T.D. The mouse forced swim test. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 59, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, A.; Dao, D.T.; Terrillion, C.E.; Piantadosi, S.C.; Bhat, S.; Gould, T.D. The tail suspension test. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 59, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, S.; File, S.E. Anxiolytic and anxiogenic drug effects on exploratory activity in an elevated plus-maze: A novel test of anxiety in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1986, 24, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walf, A.A.; Frye, C.A. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, O.; Reznick, A.Z. The role of E3 ubiquitin-ligases MuRF-1 and MAFbx in loss of skeletal muscle mass. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, N.; Klaude, M.; Lundell, L.; Thorell, A.; Rooyackers, O. Autophagic-lysosomal pathway is the main proteolytic system modified in the skeletal muscle of esophageal cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer-Guittaut, M.; Poillet, L.; Liang, Q.; Bôle-Richard, E.; Ouyang, X.; Benavides, G.A.; Chakrama, F.-Z.; Fraichard, A.; Darley-Usmar, V.M.; Despouy, G.; et al. The role of GABARAPL1/GEC1 in autophagic flux and mitochondrial quality control in MDA-MB-436 breast cancer cells. Autophagy 2014, 10, 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, M.; Schweiger, M.; Schreiber, R.; Campos-Olivas, R.; Tsoli, M.; Allen, J.; Swarbrick, M.; Rose-John, S.; Rincon, M.; Robertson, G.; et al. A switch from white to brown fat increases energy expenditure in cancer-associated cachexia. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kir, S.; White, J.P.; Kleiner, S.; Kazak, L.; Cohen, P.; Baracos, V.E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Tumour-derived PTH-related protein triggers adipose tissue browning and cancer cachexia. Nature 2014, 513, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, S.E.; Calcaterra, S.L.; Brooker, R.M.; Huber, C.M.; Guzman, R.E.; Juneau, P.L.; Schrier, D.J.; Kilgore, K.S. Weight bearing as a measure of disease progression and efficacy of anti-inflammatory compounds in a model of monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2003, 11, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyart, E.; Bindels, L.B.; Mina, E.; Menga, A.; Stanga, S.; Porporato, P.E. Cachexia, a Systemic Disease beyond Muscle Atrophy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, K.A.; Zhu, X.; Burfeind, K.G.; Krasnow, S.M.; Levasseur, P.R.; Morgan, T.K.; Marks, D.L. Establishment and characterization of a novel murine model of pancreatic cancer cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Cai, J.; Guo, X.; Tang, Y.; Wan, J.; Su, D.-F.; Liu, X. The Acute-Phase Protein Orosomucoid Regulates Food Intake and Energy Homeostasis via Leptin Receptor Signaling Pathway. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandarian, S.C.; Nosacka, R.L.; Delitto, A.E.; Judge, A.R.; Judge, S.M.; Ganey, J.D.; Moreira, J.D.; Jackman, R.W. Tumour-derived leukaemia inhibitory factor is a major driver of cancer cachexia and morbidity in C26 tumour-bearing mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, Y.; Kogita, A.; Sakamoto, H.; Hayashi, H.; Terashima, M.; de Velasco, M.A.; Sakai, K.; Fujita, Y.; Tomida, S.; Kitano, M.; et al. Activin Signal Promotes Cancer Progression and Is Involved in Cachexia in a Subset of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 356, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, A.L.; Dantas, E.; Ramsamooj, S.; Murthy, A.; Ahmed, M.; Zunica, E.R.M.; Liang, R.J.; Murphy, J.; Holman, C.D.; Bare, C.J.; et al. Blocking ActRIIB and Restoring Appetite Reverses Cachexia and Improves Survival in Mice with Lung Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loumaye, A.; de Barsy, M.; Nachit, M.; Lause, P.; Frateur, L.; van Maanen, A.; Trefois, P.; Gruson, D.; Thissen, J.P. Role of Activin A and myostatin in human cancer cachexia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 2030–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molfino, A.; Amabile, M.I.; Imbimbo, G.; Rizzo, V.; Pediconi, F.; Catalano, C.; Emiliani, A.; Belli, R.; Ramaccini, C.; Parisi, C.; et al. Association between Growth Differentiation Factor-15 (GDF-15) Serum Levels, Anorexia and Low Muscle Mass among Cancer Patients. Cancers 2020, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Wu, G.; Ning, J.; Yan, J.; Yang, J.; Kang, J. Neutralizing antibody against GDF15 for treatment of cancer-associated cachexia. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.; Hughes, C.; Murray, L.; Parsons, C.; Cantwell, M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of cancer cachexia: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clamon, G.; Byrne, M.M.; Talbert, E.E. Inflammation as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer Cachexia. Cancers 2022, 14, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobs, A.S.; Boccia, R.V.; Croot, C.C.; Gabrail, N.Y.; Dalton, J.T.; Hancock, M.L.; Johnston, M.; Steiner, M.S. Effects of enobosarm on muscle wasting and physical function in patients with cancer: A double-blind, randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Goto, M.; Fukunishi, S.; Asai, A.; Nishiguchi, S.; Higuchi, K. Cancer Cachexia: Its Mechanism and Clinical Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, J.B.; Wright, D.N.; McDonald, J.W.; Corner, J.L. The prevalence of concern about weight loss and change in eating habits in people with advanced cancer. J. Pain. Symptom. Manag. 2006, 32, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K.; Froggatt, K. Loss of weight and loss of appetite in advanced cancer: A problem for the patient, the carer, or the health professional? Palliat. Med. 2002, 16, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utech, A.E.; Tadros, E.M.; Hayes, T.G.; Garcia, J.M. Predicting survival in cancer patients: The role of cachexia and hormonal, nutritional and inflammatory markers. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2012, 3, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.; Atagi, S.; Imamura, F.; Tanaka, H.; Minato, K.; Harada, T.; Katakami, N.; Yokoyama, T.; Yoshimori, K.; Takiguchi, Y.; et al. Quality of life and survival survey of cancer cachexia in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients-Japan nutrition and QOL survey in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer study. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3473–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Op den Kamp, C.M.; Langen, R.C.; Snepvangers, F.J.; de Theije, C.C.; Schellekens, J.M.; Laugs, F.; Dingemans, A.M.; Schols, A.M. Nuclear transcription factor kappa B activation and protein turnover adaptations in skeletal muscle of patients with progressive stages of lung cancer cachexia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, C.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; McCargar, L.J.; Reiman, T.; Sawyer, M.B.; Martin, L.; Baracos, V.E. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.-L.; Au, P.C.-M.; Lee, G.K.-Y.; Li, G.H.-Y.; Chan, M.; Cheung, B.M.-Y.; Wong, I.C.-K.; Lee, V.H.-F.; Mok, J.; Yip, B.H.-K.; et al. Different Definitions of Sarcopenia and Mortality in Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2021, 7, S34–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhudaryan, A.; Scherbakov, N.; Springer, J.; Doehner, W. Cardiac muscle wasting in individuals with cancer cachexia. ESC Heart Fail. 2017, 4, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, J.; Tschirner, A.; Haghikia, A.; von Haehling, S.; Lal, H.; Grzesiak, A.; Kaschina, E.; Palus, S.; Potsch, M.; von Websky, K.; et al. Prevention of liver cancer cachexia-induced cardiac wasting and heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Nishijima, Y.; Asp, M.L.; Stout, M.B.; Reiser, P.J.; Belury, M.A. Cardiac alterations in cancer-induced cachexia in mice. Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 37, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M. Protein breakdown in cancer cachexia. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 54, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellock, F.G.; Riedinger, M.S.; Fishbein, M.C. Brown adipose tissue in cancer patients: Possible cause of cancer-induced cachexia. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1986, 111, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Bos, S.A.; Gill, C.M.; Torriani, M.; Bredella, M.A. Brown adipose tissue and cancer progression. Skelet. Radiol. 2020, 49, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paval, D.R.; Patton, R.; McDonald, J.; Skipworth, R.J.E.; Gallagher, I.J.; Laird, B.J. A systematic review examining the relationship between cytokines and cachexia in incurable cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, J.; Zahra, A.; Venugopal, S.; Selvamani, T.Y.; Shoukrie, S.I.; Selvaraj, R.; Dhanoa, R.K.; Hamouda, R.K.; Mostafa, J. What Role Do Inflammatory Cytokines Play in Cancer Cachexia? Cureus 2022, 14, e26798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, L.; Hayes, T.G.; Tao, N.; Krieger, B.; Feng, B.; Wu, Z.; Nicoletti, R.; Isabel Chiu, M.; Gyuris, J.; Garcia, J.M. Plasma Growth Differentiation Factor 15 Is Associated with Weight Loss and Mortality in Cancer Patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015, 6, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dev, R. Measuring cachexia-diagnostic criteria. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2019, 8, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, M.; Samols, D.; Kushner, I. STAT3 Participates in Transcriptional Activation of the C-reactive Protein Gene by Interleukin-6. J. Boil. Chem. 1996, 271, 9503–9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omlin, A.; Blum, D.; Wierecky, J.; Haile, S.R.; Ottery, F.D.; Strasser, F. Nutrition impact symptoms in advanced cancer patients: Frequency and specific interventions, a case–control study. J. Cachex Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasanchi, A.; Nemani, S.; Pandey, S.; Del Fabbro, E. Managing Nutrition Impact Symptoms in Cancer Cachexia: A Case Series and Mini Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 831934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.N.; Olson, K.; Kubrak, C.; Parliament, M.; Ghosh, S. Validation of the Head and Neck Patient Symptom Checklist as a nutrition impact symptom assessment tool for head and neck cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 21, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, O.; Strasser, F.; Radbruch, L.; Stone, P. Identification of factors associated with fatigue in advanced cancer: A subset analysis of the European palliative care research collaborative computerized symptom assessment data set. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 43, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, R.D.; Vigano, A.; Trutschnigg, B.; Hornby, L.; Lucar, E.; Bacon, S.L.; Morais, J.A. Cancer-related fatigue: The impact of skeletal muscle mass and strength in patients with advanced cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010, 1, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, A.; Busquets, S.; Ponce, M.; Toledo, M.; Guàrdia-Olmos, J.; Peró-Cebollero, M.; López-Soriano, F.J.; Argilés, J.M. The animal cachexia score (ACASCO). Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2019, 2, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, M.; Penna, F.; Busquets, S.; Lopez-Soriano, F.J.; Argiles, J.M. Distinct behaviour of sorafenib in experimental cachexia-inducing tumours: The role of STAT3. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzu, M.; Nonaka, M.; Miyano, K.; Sato, H.; Kurebayashi, N.; Yanagihara, K.; Sakurai, T.; Hisaka, A.; Uezono, Y. A novel strategy for treatment of cancer cachexia targeting xanthine oxidase in the brain. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 140, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, P.; Unger, C.A.; Patton, E.A.; Aiken, A.; Browne, A.; James, E.; Aladhami, A.K.; Hope Rd, M.C.; VanderVeen, B.N.; Cardaci, T.D.; et al. Platelet status in cancer cachexia progression in ApcMin/+ mice. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1253587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puppa, M.J.; White, J.P.; Sato, S.; Cairns, M.; Baynes, J.W.; Carson, J.A. Gut barrier dysfunction in the apc(min/+) mouse model of colon cancer cachexia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narsale, A.A.; Enos, R.T.; Puppa, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Murphy, E.A.; Fayad, R.; Pena, M.O.; Durstine, J.L.; Carson, J.A. Liver Inflammation and Metabolic Signaling in ApcMin/+ Mice: The Role of Cachexia Progression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzuk, M.M.; Finegold, M.J.; Mather, J.P.; Krummen, L.; Lu, H.; Bradley, A. Development of cancer cachexia-like syndrome and adrenal tumors in inhibin-deficient mice. Proc. Nal. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8817–8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.L.; Lu, J.; Song, Y.; Kwak, K.S.; Jiao, Q.; Rosenfeld, R.; Chen, Q.; Boone, T.; Simonet, W.S.; et al. Reversal of cancer cachexia and muscle wasting by ActRIIB antagonism leads to prolonged survival. Cell 2010, 142, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kumar, R.; Underwood, K.; O’Connor, A.E.; Loveland, K.L.; Seehra, J.S.; Matzuk, M.M. Prevention of cachexia-like syndrome development and reduction of tumor progression in inhibin-deficient mice following administration of a chimeric activin receptor type II-murine Fc protein. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 13, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequences (Forward and Reverse, 5′-3′) | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|

| Gapdh | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA | NM_008084 |

| Atrogin | CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG AGGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATC | NM_026346 |

| MuRF-1 | TCCTGATGGAAACGCTATGGAG ATTCGCAGCCTGGAAGATGT | NM_001039048 |

| Bnip3 | CAGAGCGGGGAGGAGAAC GAGGCTGGAACGCTGCTC | NM_009760 |

| Gabarapl1 | GGACCACCCCTTCGAGTATC CCTCTTATCCAGATCAGGGACC | NM_020590 |

| Ucp1 | AAGCTGTGCGATGTCCATGT AAGCCACAAACCCTTTGAAAA | NM_009463 |

| Dio2 | AAGCTGTGCGATGTCCATGT AAGCCACAAACCCTTTGAAAA | NM_010050 |

| Apcs | AGACAGACCTCAAGAGGAAAGT AGGTTCGGAAACACAGTGTAAAA | NM_011318 |

| Interleukin 1β (IL-1β) | GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT | NM_008361 |

| Orm1 | CGAGTACAGGCAGGCAATTCA ACCTATTGTTTGAGACTCCCGA | NM_008768 |

| Model | Species | Cell/Induction Method | Injection Site/Tumor Site | Time to Onset of Cachexia (Body Weight Loss) | Report of an Experiment on the Effects of NIS | Cancer Pain Characteristics | Study Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Lung Carcinoma CIBP model | Mouse (C57BL/6) | Lewis lung cancer injection (5 × 104 cells) | Femoral bone marrow cavity | 3–4 weeks (post-transplantation) | Depression: FST, TST Anxiety: EPM Pain: Weight bearing, von Frey test, cold plate tests | Cancer-induced bone pain (quantifiable). | Rapidly progressive cachexia. Not suitable for long-term studies. | In this study, [35] |

| Lewis Lung Carcinoma model | Mouse (C57BL/6) | Lewis lung cancer injection (5 × 105~1 × 106 cells) | Subcutaneous (flank) or intramuscular | 1–2 weeks (post-transplantation) | Depression: FST, TST | Localized pain may be caused by the tumor compressing the surrounding tissues (not quantifiable). | Rapidly progressive cachexia. Not suitable for long-term studies. | [24,29,83,84] |

| C26 mouse colon cancer model | Mouse (BALB/c, CD2F1) | Colon-26 injection (5 × 105~1 × 106 cells) | Subcutaneous (flank) or intramuscular | 1–3 weeks (post-transplantation) | Depression: FST, TST Anxiety: EPM | Localized pain may be caused by the tumor compressing the surrounding tissues (not quantifiable). | Rapidly progressive cachexia. Not suitable for long-term studies. | [22,29,83,84] |

| B16F10 mouse melanoma model | Mouse (C57BL/6) | B16F10 injection (5 × 104~1 × 106 cells) | Subcutaneous | 1–3 weeks (post-transplantation) | Fatigue: Total locomotion activity | Localized pain may be caused by the tumor compressing the surrounding tissues (not quantifiable). | Rapidly progressive cachexia. Not suitable for long-term studies. | [24,84] |

| 85As2 human gastric cancer model | Immunodeficient animals (BALB/c nu/nu mice, F344/NJcl-rnu/rnu rats) | 85As2 injection (1 × 106~1 × 107 cells) | Subcutaneous | 1–2 weeks (post-transplantation) | No reports | Potential for localized pain due to tumor compression of surrounding tissues (not quantifiable). | Rapidly progressive cachexia. Not suitable for long-term studies. | [25,85] |

| Yoshida AH-130 rat hepatoma cell model | Rat (Wistar) | Yoshida AH-130 injection (1 × 108 cells) | Intraperitoneal | 1–2 weeks (post-transplantation) | Depression: FST | Potential for localized pain due to tumor compression of surrounding tissues (not quantifiable). | Rapidly progressive cachexia. Not suitable for long-term studies. | [26,83] |

| Apc Min/+ mouse model | Mouse (Genetic mutation) | Spontaneous mutation in the Apc gene | Intestinal tract (mainly colon) | 12–20 weeks of age | Fatigue: Total locomotion activity | Minimal direct pain: however, tumor burden can cause discomfort and a decrease in activity (not quantifiable). | Prenatal genetic modification may affect development. | [27,86,87,88] |

| Inhibin alpha subunit knockout model | Mouse (Genetically modified) | Genetic modification (Inhhibin α (-/-)) | Gonadal and adrenal | 6–12 weeks of age | No reports | Minimal direct pain: however, tumor burden can cause discomfort and a decrease in activity (not quantifiable). | Prenatal genetic modification may affect development. | [28,89,90,91] |

| KPP model | Mouse (Genetically modified) | Genetic modification (Ptf1aCre-ERTM; KrasLSL-G12D; Pten-flox) | Pancreas | Between 75 and 90 days after tamoxifen administration. (Initiated with tamoxifen between 24 and 28 days (Tumor formation). Median survival 3.5 months) | Fatigue: Total locomotion activity | Pancreatic tumor enlargement, nerve invasion, and local tissue compression may cause pain (not quantifiable). | Lose normal pancreatic parenchyma. | [29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasegawa, T.; Kawahara, K.; Sato, K.; Asano, Y.; Maeda, T. Characterization of a Cancer-Induced Bone Pain Model for Use as a Model of Cancer Cachexia. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 13364-13382. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120797

Hasegawa T, Kawahara K, Sato K, Asano Y, Maeda T. Characterization of a Cancer-Induced Bone Pain Model for Use as a Model of Cancer Cachexia. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2024; 46(12):13364-13382. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120797

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasegawa, Takuya, Kohichi Kawahara, Koji Sato, Yoshihisa Asano, and Takehiko Maeda. 2024. "Characterization of a Cancer-Induced Bone Pain Model for Use as a Model of Cancer Cachexia" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 46, no. 12: 13364-13382. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120797

APA StyleHasegawa, T., Kawahara, K., Sato, K., Asano, Y., & Maeda, T. (2024). Characterization of a Cancer-Induced Bone Pain Model for Use as a Model of Cancer Cachexia. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 46(12), 13364-13382. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120797