A Competency Framework for Teaching and Learning Innovation Centers for the 21st Century: Anticipating the Post-COVID-19 Age

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Teaching and Learning Centers: History and Models

3. The PROF-XXI Framework

4. Methods

4.1. Research Objective and Design

4.2. Participants and Sample

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. The PROF-XXI Framework as a Tool for Analyzing Institutional Teaching and Learning Competencies Development

5.2. The PROF-XXI Framework as a Tool for Analyzing and Understanding the Evolution of TLCs Strategy

6. Conclusions and Implications

7. Limitations and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Framework/Model | Description |

|---|---|

| Teachers’ Focus | |

| European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu) | DigCompEdu was published in late 2017 by the Joint Research Centre of the European Union (JRC) (Redecker & Punie, 2017). Its main objective is to align the European educational policies with such a reference framework. DigCompEdu is a digital competence model with six differentiated competence areas: Professional engagement, Digital resources, Teaching and Learning, Assessment, Empowering learners, and Facilitating learners’ digital competence. Each area has a series of competencies that “teachers must have in order to promote effective, inclusive and innovative learning strategies, using digital tools” (Redecker y Punie, 2017, p. 4). |

| UNESCO ICT Competence Framework for Teachers (ICT-CFT) | This framework, developed by UNESCO, presents “a wide range of competencies that teachers need in order to integrate ICT in their professional practice” (Butcher, 2019, p. 2). It fosters practical knowledge of the advantages that ICT provides in education systems. Moreover, it suggests that teachers, apart from acquiring competencies related to ICT, must be able to use these to help their students to become collaborative, creative, innovative, committed, and decisive citizens (Rodríguez et al., 2018). This framework presents six fundamental areas or aspects of the professional teaching practice: Understanding ICT in the educational policies, Curriculum and evaluation, Pedagogy, Application of digital abilities, Organization and administration, and Professional learning. |

| Common Spanish Framework of Digital Competence for Teachers of the “Spanish Institute of Educational Technology and Teacher Training | The Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport launched a project in 2012 to define the Common Framework of Digital Competence for Teachers, updated four times (Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y Formación del Profesorado, INTEF, 2017a, 2017b). It is based on the DigComp Framework of Digital Competence for Citizens (Carretero, Vuorikari, & Punie, 2017; Vuorikari, Punie, Carretero, & Van-Den-Brande, 2016). It is a generic digital competence model for educators. The competence areas (5) and competencies (21) are those of the DigComp framework. |

| British Framework of Digital Teaching | The British Framework of Digital Teaching was created by the Education and Teaching Foundation (ETF) in association with the JISC company (Education and Training Foundation, 2019). Its main objective is to increase the understanding of teachers in the use of digital technologies to enrich their teaching practices and improve their professional development (Pérez-Escoda et al., 2019). This framework consists of seven key areas, with three levels for each of them: exploration, adaptation, and leadership. The seven elements are Pedagogical Planning, Pedagogical Approach, Employability of the Students, Specific Teaching, Evaluation, Accessibility and Inclusion, and Self-development. |

| ICT Competencies and Standards for the Teaching profession of the Chilean Ministry of Education | The Education and Technology Centre of the Chilean Ministry of Education published this framework in the year 2011, as an updated version of a previous framework published in 2006 (Elliot, Gorichon, Irigoin, & Maurizi, 2011). It presents five dimensions aligned with the UNESCO Framework of ICT Competencies for Teachers (Butcher, 2019). All five dimensions work through descriptors, criteria and competencies. Moreover, each standard allows teachers to recognize how to use and integrate ICTs, identify their training needs, and define personalized training itineraries (Ríos, Gómez, & Rojas, 2018). |

| Framework of Implementing Collaborative Learning in the Classroom (ICLC) | The ICLC framework is based on the metacognitive framework of teacher practice by Artzt and Armour-Thomas (1998) that describes teaching in analogy to the cognitive process of solving a problem in three phases: a pre-active phase, an inter-active phase, and a post-active phase (cf. Jackson 1968). While the framework focuses on the teacher level, the student level is also presented in the framework, as the teacher’s goal is to ensure a high quality of student interaction, on which the effectiveness of collaborative learning depends (Dillenbourg et al., 1996; Kobbe et al., 2007; Webb, 1989). The ICLC framework distinguishes between five teacher competencies that span across all implementation phases of collaborative learning: the ability to plan student interaction, monitor, support, and consolidate this interaction, and finally reflect upon it. |

| Students’ Focus | |

| Framework of the “International Society for Technology in Education” (ISTE) for teachers | The International Society for Technology in Education develops this competence framework focusing on the needs of the students of the 21st century (Crompton, 2017). Its main objective is to delve into the teaching practice, promote student collaboration, rethink the traditional approaches, and boost autonomous learning (Crompton, 2017; ISTE, 2018; Pérez-Escoda, García-Ruiz, & Aguaded, 2019). The general teacher profile is characterized by being active and innovative in the teaching–learning process (Gutiérrez-Castillo, Cabero, Almenara, & Estrada-Vidal, 2017). Thus, the ISTE standards for teachers are divided into seven roles or profiles that an educator must develop along his/her professional career. Framework with seven differentiated competence areas: Learners, Leaders, Citizens, Collaborators, Designers, Facilitators, and Analysts. |

| Managers’ Focus | |

| ICT Competencies for Teachers’ Professional Development of Colombian Ministry of Education | The model proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Education aims to guide the professional development of teachers to improve educational innovation with ICT (Fernanda, Saavedra, Pilar, Barrios, & Zea, 2013). It is targeted at both designers of training programs and teachers interested in generating ICT-enriched environments: relevant, practical, established, collaborative and inspiring (Hernández-Suárez, 2016). This framework has five competencies that teachers must develop: Technological, Communicative, Pedagogical, Management, and Research. |

| Framework for the Center for Teaching Development and Innovation (Centro de Desarrollo e Innovación de La Docencia (CeDID) at the Universidad Católica de Temuco (UCT)) | A framework for the evaluation of educational development programs in Chile. This framework was designed to support the diverse needs of different stakeholders: (1) faculty to make judgments about their teaching in their school and disciplinary context; (2) the learning center to evidence the impact of their educational development programs; (3) the university to inform its attainment of its planned strategic goals; and finally (4) the ministry on the effectiveness and impact of the programs that it has funded. The CeDID Evaluation Framework drew on Guskey’s five-level model, which identifies where educational development programs can demonstrate impact (Chalmers & Gardiner, 2015). These are (1) Teachers’ reaction to the development program; (2) Conceptual changes in teachers’ thinking; (3) Behavioral changes in the way teachers use the knowledge, skills and techniques learners; (4) Changes in organizational culture, practices, and support; and (5) Changes in student learning, engagement, perception, study approaches. |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Introduction

Appendix B.2. Context

Appendix B.3. The PROF-XXI Framework

Appendix B.3.1. Levels of Competence of the TLCs

- Level 1 or “Development”: This is the first level of competencies and defines the basic competencies that any TLC should have to start its activities in the institution. Institutions at this level are able to identify innovative teaching practices, needs of their students and other stakeholders, and systematize prior learning about their activity in digital education.

- Level 2 or “Innovation”: This is the second level of competencies and defines the competencies that TLCs must have in order to be able to generate and promote educational innovation in their institution. Institutions at this level are capable of installing new educational experiences of references, promoting the use of technologies and the most innovative teachers, as well as generating opportunities for training and exchange of good practices among the different actors in the institution.

- Level 3 or “Value generation”: This is the third level of competencies and defines the competencies that the TLCs must have in order to be able to generate value in their institutions, generating changes and promoting transformations that affect their culture. Institutions at this level are able to disseminate new models of training and excellence to promote change, increase the educational quality of the institution, contribute to the cultural transformation of the institution, promote the installation of good practices in the use of technology and generate evidence on new practices to support decision-making.

- Level 4 or “New Challenges and Opportunities”: This is the fourth level of competencies and defines the competencies that TLCs should have to identify new institutional challenges related to innovation and teaching quality. Institutions at this level must be able to identify and visualize new horizons on teaching practice and quality learning scenarios that enhance student learning, define indicators and metrics that allow for the evaluation of educational innovations, involve the institution’s stakeholders at various levels and systematize these challenges from the information collected into concrete actions for the institutional strategy.

- Level 5 or “Public accountability of impacts for continuous improvement”: This is the fifth and highest level of competencies and defines the competencies that TLCs must have to be able to ensure the monitoring and transparency of the actions carried out by the TLC in order to assess their impact and make this impact visible through both internal and public reporting and research on these actions.

Appendix B.3.2. Competence Dimensions of TLCs

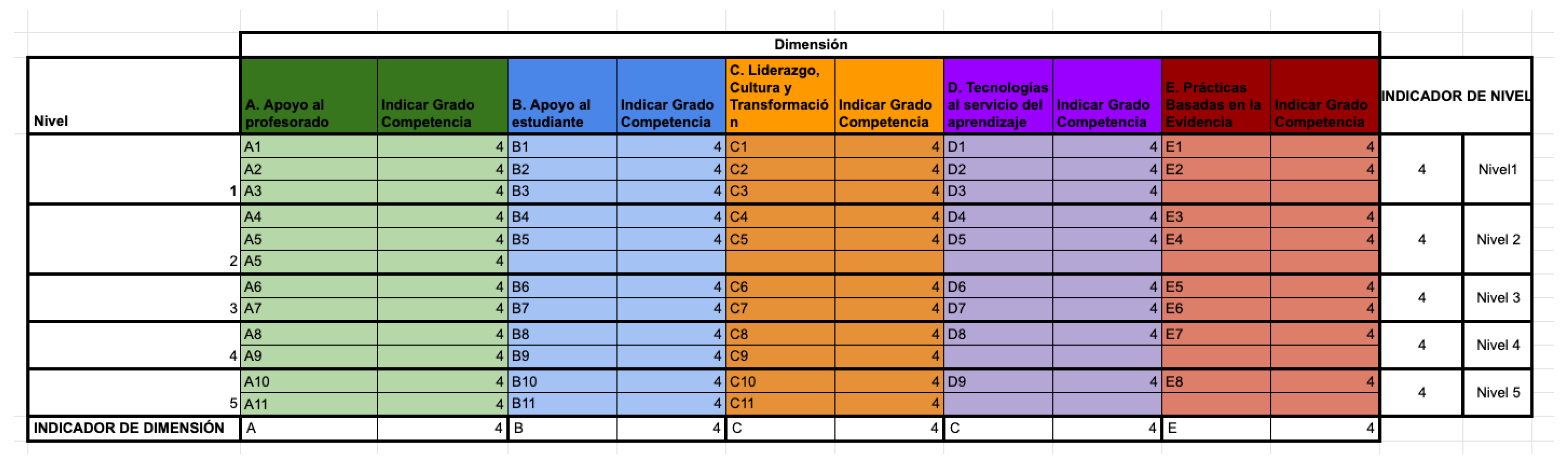

- Dimension A or “Support for teaching”: Dimension A refers to those competencies of the TLC that are related to supporting teaching processes. Actions related to these competencies will have a direct effect on teachers in the institution. This dimension defines three competencies for level 1 (A1–A3), three for level 2 (A4–A6), two for level 3 (A7 and A8), one for level 4 (A9) and two for level 5 (A10 and A11).

- La Dimension B or “Student support”: Dimension B refers to the competencies of the TLC that are related to student support. Actions related to these competencies will have a direct effect on the students of the institution. This dimension defines three competencies for level 1 (B1-B3), two for level 2 (B4 and B5), two for level 3 (B6 and B7), two for level 4 (B8 and B9) and two for level 5 (B10 and B11).

- Dimension C or “Leadership, Culture and Transformation”: Dimension C refers to TLC competencies that are related to leadership initiatives that promote a cultural transformation of the institution towards educational innovation. Actions related to these competencies will have a direct effect on the internal processes of the institution, both in its practices and policies. This dimension defines three competencies for level 1 (C1–C3), two for level 2 (C4 and C5), two for level 3 (C6 and C7), two for level 4 (C8 and C9) and two for level 5 (C10 and C11).

- Dimension D or “Technology at the service of learning”: Dimension D refers to the competencies of the TLC that are related to technological educational initiatives, both in terms of practices and infrastructures (tools, services...). Actions related to these competencies will have a direct effect on the development of the institution’s technological infrastructures as well as its educational models, conditioned by these infrastructures. This dimension defines three competencies for level 1 (D1–D3), two for level 2 (D4 and D5), two for level 3 (D6 and D7), one for level 4 (D8) and one for level 5 (D9).

- Dimension E or “Evidence-based practice”: Dimension D refers to the competencies of the TLC that are related to initiatives that aim to collect data and information to understand the effect of the transformations and initiatives carried out in education. Actions related to these competencies will have a direct effect on the evaluation of the institutional initiatives carried out, and the TLC itself may affect decision-making in the definition of concrete policies and initiatives. This dimension defines two competencies for level 1 (E1 and E2), two for level 2 (E3 and E4), two for level 3 (E5 and E6), one for level 4 (E7) and one for level 5 (E8).

Appendix B.4. Use of the PROF-XXI Framework

Appendix B.4.1. The PROF-XXI Framework as a Reference and a Form of Internal Assessment

| Grade 1 (Minor) | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 (Major) |

|---|---|---|---|

| My institution/center does not have this competence | My institution/center is moderately prepared in this competence | My institution/center is moderately prepared in this competency | My institution/center is prepared in this competency |

- LEVEL INDICATOR: This numerical value is calculated by adding up all the degrees of competence of the competencies associated to a level and dividing this value by the number of competencies in this level. For example, to calculate level 1, all the degrees of competence of the different dimensions of level 1 (A1 + A2 + A3 + B1 + B2 + B3 + C1 + C2 + C3 + D1 + D2 + D3 + E1 + E2)/11 will be added up.

- DIMENSION INDICATOR. This numerical value is calculated by adding up all the degrees of competence of the competencies associated with a dimension and dividing it by the number of competencies in this dimension. For example, to calculate the value of dimension A, all the degrees of competence of the different dimensions of level 1 (A1 + A2 + ...+ A11)/12 will be added together.

Appendix B.4.2. The PROF-XXI Framework as a Reference for Strategic Planning

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Institution | Role in the University | Participants | Average of A. Teachers’ Support | Average of B. Students’ Support | Average of C. Leadership, Culture and Transformation | Average of D. Technology for Learning | Average of D. Evidence-Based Practice | Average per Competence per Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1 (U. San Carlos de Guatemala) | Administrative | 11 | 2.51 (SD = 0.74) | 2.44 (SD = 0.82) | 2.58 (STD = 1) | 2.61 (SD = 0.95) | 2.63 (SD = 1.14) ** | 2.55 |

| Manager | 6 | 2.45 (SD = 0.70) | 2.45 (SD = 9.57) | 2.55 (STD = 0.68) ** | 2.65 (SD = 0.38) ** | 2.58 (SD = 0.62) | 2.54 | |

| Teaching/Academic | 9 | 2.69 (SD = 0.55) ** | 2.47 (SD = 0.75) ** | 2.55 (STD = 0.82) | 2.52 (SD = 0.61) | 2.22 (SD = 0.84) | 2.11 | |

| Total U1 | 26 | 2.56 (SD = 0.65) | 2.45 (SD = 0.72) | 2.56 (STD = 0.84) | 2.59 (SD = 0.72) | 2.48 (SD = 0.93) | 2.55 | |

| U2 (U. Galileo) | Administrative | 8 | 3.39 (SD = 0.57) ** | 3.13 (SD = 0.74) ** | 2.95 (SD = 0.85) ** | 3.25 (SD = 0.72) ** | 2.92 (SD = 1.05) ** | 3.13 |

| Manager | 2 | 3.00 (SD = 0.64) | 2.95 (SD = 0.71) | 2.82 (SD = 0.64) | 3.11 (SD = 0.47) | 2.75 (SD = 0.71) | 2.93 | |

| Teaching/Academic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total U2 | 10 | 3.32 (SD = 0.57) | 3.09 (SD = 0.70) | 2.93 (SD = 0.78) | 3.22 (SD = 0.66) | 2.89 (SD = 0.96) | 3.09 | |

| U3 (San Buenaventura) | Administrative | 5 | 3.99 (SD = 0.65) ** | 2.93 (SD = 0.53) ** | 2.95 (SD = 0.82) ** | 2.76 (SD = 0.84) | 2.85 (SD = 0.76) | 2.41 |

| Manager | 5 | 2.67 (SD = 0.88) | 2.82 (SD = 0.71) | 2.93 (SD = 0.64) | 2.96 (SD = 0.58) ** | 2.88 (SD = 0.73) ** | 2.85 | |

| Teaching/Academic | 13 | 2.69 (SD = 0.46) | 2.94 (SD = 0.56) | 2.94 (SD = 0.42) | 2.81 (SD = 0.58) | 2.72 (SD = 0.67) | 2.82 | |

| Total U3 | 23 | 2.75 (SD = 0.59) | 2.91 (SD = 0.56) | 2.94 (SD = 0.54) | 2.83 (SD = 0.62) | 2.78 (SD = 0.67) | 2.84 | |

| U4 (U. Cauca) | Administrative | 1 | 3.00 ** | 2.45 | 3.36 ** | 3.22 ** | 3.13 ** | 3.03 |

| Manager | 1 | 2.36 | 2.09 | 2.18 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.13 | |

| Teaching/Academic | 22 | 2.81 (SD = 0.67) | 2.72 (SD = 0.72) ** | 2.57 (SD = 0.68) | 2.52 (SD = 0.72) | 2.32 (SD = 0.87) | 2.59 | |

| Total U4 | 24 | 2.80 (SD = 0.67) | 2.68 (SD = 0.70) | 2.59 (SD = 0.67) | 2.52 (SD = 0.71) | 2.34 (SD = 0.85) | 2.55 | |

| Total general | 83 | 2.77 (SD = 0.66) ** | 2.72 (SD = 0.69) | 2.72 (SD = 0.72) | 2.71 (SD = 0.71) | 2.57 (SD = 0.85) | - |

| Partial Result Code | Description | Supporting Data Source (Table A2 and Table A3) |

|---|---|---|

| PR1.1 | In all institutions, the competence is Competence “A. Teacher support” was valued as one of the most developed. | Competence A is evaluated with the highest values (2.77; SD = 0.66), compared with other competencies B (2.72; SD = 0.69); C (2.72; SD = 0.72); D (2.71; SD = 0.71); and E (2.57; SD = 0.85) (Table A2) |

| PR1.2 | All institutions, evaluated Competence E “Evidence-based practices” as the least developed | Competence E is evaluated with the lowest value (2.57; SD = 0.85), compared with other competencies A (2.77; SD = 0.66); B (2.72; SD = 0.69); C (2.72; SD = 0.72); and D (2.71; SD = 0.71) (Table A2) |

| PR1.3 | Participants from U2 and U4 evaluated the Competence “A. Teachers’ support” as the most well-developed competence in the institution, and the Competence “E. Evidence-based practices” as the least developed. | Competence A in U2 is evaluated with the highest value (3.31; SD = 0.57), while Competence E (2.89; SD = 0.96) with the lowest, compared with other competencies B (3.09; SD = 0.70); C (2.93; SD = 0.78); D (3.22; SD = 0.66) (Table A2) Competence A in U4 is evaluated with the highest value (2.80; SD = 0.67), while Competence E (2.34; SD = 0.85) with the lowest, compared with other competencies B (2.68; SD = 0.70); C (2.57; SD = 0.67); D (2.52; SD = 0.71) (Table A2) |

| PR1.4 | In all institutions, the “Manager Staff” evaluates the competence “A. Teachers’ support” with the lowest values, together with the “Teaching Staff” from U3. However, “Teaching/Academic Staff” from U1 and U4 evaluated it as the most well-developed. | Values for Competence A for competencies and all stakeholders in the following order (Table A2): (1) Administrative: U1 (2.51; SD = 0.74) U2 (3.39; SD = 0.57); U3 (3.39; SD = 0.57); U4 (3, 00). (2) Manager: U1 (2.45; SD = 0.70) U2 (3.00; SD = 0.64); U3 (2.67; SD = 0.88); U4 (2.36). (3) Teaching/Academic: U1 (2.69; SD = 0.55) U2 (-); U3 (2.69; SD = 0.46); U4 (2.81; SD = 0.69). |

| PR1.5 | Institution U2 has reported the highest values in terms of competence dimensions and compared with the other institutions. | Competence values in Table A2. |

| Partial Result Code | Description | Selected Supporting Data (Translated from the Original Data) |

|---|---|---|

| PR2.1 | To the Competence “A. Teacher support”, institutions associated initiatives for training the teachers. The types of trainings vary in frequency and format depending on the institution, including courses, workshops, seminars, and diplomas (a set of courses with several CETS credits). Most of trainings focus on learning about digital tools. Participants also associate to these competencies’ initiatives related with teaching recognition, teaching evaluation and the share of good practices. | “Training courses for teachers in new digital tools” (U1) “Creation of a support and training unit to support teachers in virtual education. Training for teachers in the use of ICT. Workshops on good practices in Moodle, Meet, zoom, classroom and other tools” (U4) “Training for teachers” (U3) “Monthly training workshops on the use of the institutional educational platform” (U2) “Sharing and supporting teachers’ successful experiences” (U4) “Learning from different experiences that led to good practices” (U4) “Evaluation on the teaching practice carried out” (U4) “Recognition of the teaching work” (U2) |

| PR2.2 | To the Competence “B. Student support” participants associated initiatives such as online courses, video tutorials as well as academic support or on the Learning Management Systems employed by the university. Participants also recognize that, in some cases, the Competence “Student Support” is a bit poor. | “Facilitate technological tools for cooperative, collaborative and participatory work” (U1) “Only some help for internet connection” (U4) “Support to the student through a web page” (U2) “Video-lecture for the laboratory sessions” (U2) |

| PR2.3 | To the competence “C. Leadership, Culture and Transformation” participants associated activities such as: (1) programs for developing the sense of belonging to the institution and its culture; (2) instances for self-evaluation, and instances for interacting with other institutions through research international programs. They also mentioned activities addressed to teaching/academics and administration staff related with the digital transformation of institutional processes. | “ Institutional Membership Program” (to promote the sense of belonging to the institution) (U2) “Organizational culture program” (U2) “TLC project and organizational culture focused on innovation and presentation of results and indicators” (U3) “Summa Project: Impact of the university in its context, through continuing education programs” (U4) “Culture of continuous institutional and program self-evaluation” (U2) “Each department has a person in charge of digital education” (U4). “Group work between managers and teachers for the best choice of objectives and platforms for the new modalities of virtual teaching” (U4) “Institutional training plan in competencies oriented to Technology, Communication, pedagogy, management and research” (U1) “ICT training pathway for teachers” (U2) “Workshops on good practices: In what? Teacher support leaders” (U3) |

| PR2.4 | To the competence “D. Technology for Learning” participants associated initiatives such as training in the use of technological platforms (i.e., Moodle, Google Classroom) and tools (i.e., Google Suit) through online material, tutorials, and courses | “Support materials and tutorials for the use of digital platforms and tools” (U2) “Training in visual and audiovisual technologies, for use in virtual classes” (U4) “New tools adapted to our own institutional platform, constant innovation” (U2) “Training courses, google classroom” (U3) “Training on the use of technology in the classroom” (U1) “Implementation of technologies and educational platforms for teaching, training of students and teachers” (U3) |

| PR2.5 | To the competence “E. Evidence-based practices”, participants associated initiatives related with the use of institutional data. The refer to initiatives for monitoring teachers and students’ performance. They also associated activities and initiatives related with the continuous curriculum improvement and benchmarking initiatives looking for other institutions practices as a reference. | “Data analysis of educational data from online courses” (U4) “Learning analytics” (U4) “Curricular design based on students’ performance” (U2) “Curricular updates at the end of the semester” (U1) “Evaluation of programs to determine innovation in teaching practice Preparation of a related semester report” (U3) |

Appendix E

| Code of the Initiative | Code of the Initiative |

|---|---|

| U1.1 | Creation of the Distance Education in Virtual Environments Policy |

| U1.2 | Creation of the Division of Distance Education in Virtual Environments |

| U1.3 | Teacher training programs related to educational innovation |

| U1.4 | Creation of the RADD (Digital Teacher Support Network) |

| U1.5 | Enabling videoconferencing systems for the teachers in all academic units at the institution |

| U1.6 | Creation of official accounts for the use of the videoconferencing system |

| U1.7 | Creation of virtual classrooms with the Moodle platform for each academic unit |

| U1.8 | Workshops for teachers and administrative staff, related to communication and technological innovation |

| U1.9 | Diploma courses in digital teaching, virtual tutoring and instructional design |

| U1.10 | Manual for quality in distance education |

| U1.11 | Creation, in some academic units, a group for supporting distance learning |

| U1.12 | Creation of the first online diploma “Bachelor’s Degree in Criminology and Criminalistics” |

| U1.13 | Design and creation of educational tutorials to support teaching |

| U1.14 | Implementation of the remote supervision tool for online exams “proctorizer” in the School of Medicine and in the Bachelor’s Degree in Criminology and Criminalistics |

| U2.1 | Institutional implementation and management of an LMS: At the institutional level, the use of an LMS (Zoom, Meet) was standardized for the execution of synchronous and asynchronous sessions for academic continuity. |

| U2.2 | Hybrid education: Academic programs currently have the particularity of being hybrid given the case that students can either attend their virtual classes or review the recording of the same. |

| U2.3 | Use of tools for the improvement and quality of virtual classes: use of tools for the improvement and quality of the teaching-learning process and interactivity during the development of virtual classes. |

| U2.4 | Supporting resources for teachers: Specialized resources available to all teachers (video tutorials, guides, podcasts, websites) were created for the process of academic continuity in the digital environment. |

| U2.5 | Webinars for teachers: We implemented webinars on the different topics of our specialized programs. |

| U2.6 | Personalized management advice and accompaniment: We decentralized the mentoring and coaching carried out by the project administration, with the objective of supporting teachers in the process from moving from a traditional teaching style to a virtual learning style. |

| U2.7 | Automation of services: We conducted an automatization of certain existing processes to facilitate the access to university tools to all the educational community and assure its immediate use. |

| U2.8 | Use of simulators, Learning Scenarios: The use of simulators is established with the objective of generating learning scenarios, to create a space for collaboration and practice for students. |

| U2.9 | Formal assessment scenarios: The use of tools is implemented to strengthen the virtual teaching-learning process by creating a formal scenario for evaluation and assurance of academic integrity on the part of students. |

| U2.10 | Continuous Learning Workshops for Teaching staff: The teacher training and education strategy was implemented on a continuous basis to achieve a development of Technological pedagogical competence. |

| U3.1 | Diploma in Pedagogical Training |

| U3.2 | Diploma in Design of Virtual Learning Environments |

| U3.3 | ICT training plan for teachers |

| U3.4 | Seminar-Workshop on e-Learning Activities |

| U3.5 | TICatlón: An event to explain and show cases using ICT for educational practices |

| U3.6 | Digital Competence Teacher Training Plan |

| U4.1 | Diploma in Educational Innovations for Higher Education: training designed to encourage innovation in university teaching practice |

| U4.2 | Diploma in University Teaching: training designed and offered to university professors who have recently joined the Institution |

| U4.3 | Management of Teaching, Learning and Assessment Course: training designed and offered to university teachers in the context of the emergency remote teaching caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (it is a mini-course created from the Diploma in Educational Innovations for Higher Education, designed for a mass education environment) |

| U4.4 | Visual and Auditory Narratives course: training designed and offered to university teachers in the context of the emergency remote teaching caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, focused on the production of multi-format educational materials (designed for a mass education environment) |

| Initiatives | Period | Competence Dimensions of the PROF-XXI Framework | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | Originated | Continues | A. Teacher Support | B. Students’ Support | C. Leadership, Culture and Transformation | D. Technology for Learning | E. Evidence-Based Practices | |

| U1.1 | X | X | X | |||||

| U1.2 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| U1.3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U1.4 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U1.5 | X | X | X | |||||

| U1.6 | X | X | X | |||||

| U1.7 | X | X | X | |||||

| U1.8 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U1.9 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U1.10 | X | X | X | |||||

| U1.11 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U1.12 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U1.13 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U1.14 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| U2.1 | X | X | X | |||||

| U2.2 | X | X | X | |||||

| U2.3 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U2.4 | X | X | X | |||||

| U2,5 | X | X | ||||||

| U2.6 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U2.7 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U2.8 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U2.9 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U2.10 | X | X | X | |||||

| U3.1 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U3.2 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U3.3 | X | X | X | X | ||||

| U3.4 | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| U3.5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| U3.6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| U4.1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| U4.2 | X | X | X | |||||

| U4.3 | X | Under study | X | X | ||||

| U4.4 | X | Under study | X | X | X | |||

| TOTAL | 16 | 15 | 27 | 22 | 12 | 14 | 25 | 11 |

| Competencies Before | 12 | 5 | 7 | 13 | 6 | |||

| Competencies Originated | 10 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 3 | |||

| Competencies Continues | 15 | 10 | 9 | 18 | 9 | |||

Appendix F

| U1 | |

| Country | Guatemala |

| Type of administration | Public |

| Number of Students | 235,212 |

| Number of Academics | 6856 |

| Origins and mission | The founding of the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala (USAC) began with the management of the first bishop Francisco Marroquin to the King of Spain in his letter dated 1 August 1548, and after more than 120 years in which multiple projects were carried out to perfect the concept of a university based on the dream of a society that needed professionals to promote development, on 21 January 1676, was embodied in a Royal Charter the birth of the first university in Central America (USAC). Over time, it went through five eras where different names were established. It was with the revolution of 1944 that it was declared as a secular institution with a social orientation. USAC is the only state university; therefore, it is exclusively responsible for directing, organizing, and developing state higher education, as well as the dissemination of culture in all its manifestations. As part of its mission, it promotes research in all spheres of human knowledge, cooperating and solving national problems. USAC currently has an academic offer of more than 600 training programs that have allowed professional growth at the Central American level and the fulfillment of its motto “Go and teach everyone”. |

| Existing Teaching and Learning Center | The Teaching and Learning Center (TLC) of the Division of Distance Education in Virtual Environments of the University of San Carlos de Guatemala “EDUMEDIA” has, as its mission, to implement and innovate educational practices through knowledge management and research, as well as learning in virtual environments using educational technologies as didactic-methodological resources, to achieve the purposes of the university and for this, it has proposed strategic actions framed in six objectives: (1) develop training and capacity building activities; (2) improve the generation of digital educational content; (3) promote educational innovation projects; (4) systematize experiences and good practices; (5) reinforce the use of virtual learning spaces; and (6) carry out technological surveillance for educational innovation. Among the services offered by the EDUMEDIA TLC are (a) advice on innovation projects for virtual education; (b) pedagogical-technological training; (c) space for the design of digital educational content; (d) technological and digital content production consulting; (e) University of San Carlos de Guatemala repository of learning objects; (f) systematization of good practices; (g) LMS installation and hosting service; (h) Google Workspace for teachers; (i) live streaming. To ensure the proper functioning of the TLC, an evaluation framework has been established with indicators that measure the development of the strategic objectives. |

| Link to TLC | https://youtu.be/ON7qZh0-SbU (accessed on 21 December 2021). |

| U2 | |

| Country | Guatemala |

| Type of administration | Private |

| Number of Students | 25,000 |

| Number of Academics | 1200 |

| Origins and mission | Located in Guatemala, Galileo University is a higher education institution, the product of 40 years of constant work and effort of an elite group of academics and professionals, lead by Eduardo Suger Cofiño, Ph.D., founder and President. He has been able to put forward a completely innovative and non-traditional educational approach that Galileo calls “The revolution of education”, which is also impelled by very a clear motto: “To educate is to change visions and transform lives.” With thirty-eight years of successful experience, facing the rapid-changing times and the knowledge globalization, Galileo University has positioned itself as a relevant leader and a reference in the field of technology. This gives the University a very important role, not only in professional training, but also in the generation of knowledge, that responds to the needs of an increasingly competitive world, becoming an excellent choice for the education of the Guatemalan and Latin American new generations. Our mission is preparing professionals with world-class academic excellence, a high spirit of justice, human, and ethical values, at the service of our society by incorporating contemporary science and technology. We are committed to give everyone the opportunity to access university studies without distinction of race, social condition, or geographic location. |

| Existing Teaching and Learning Center | The Learning and Teaching Center (TLC) collaborates with the academic community at Galileo University to provide and promotes excellence in teaching and learning through different services and resources. TLC (Teaching and Learning Center) About Services Teaching support Student support Webinars Contact Us |

| Link to TLC | https://www.galileo.edu/page/cea/ (accessed on 20 December 2021). |

| U3 | |

| Country | Colombia |

| Type of administration | Private |

| Number of Students | 5000 |

| Number of Academics | 403 |

| Origins and mission | The University of San Buenaventura in Colombia was founded by the Franciscan Order in 1688, named after the exalted doctor Saint Bonaventure. In 1973, the Colegio Mayor of San Buenaventura requested the change of its name to the University of San Buenaventura, an application that was accepted and ratified by Decree 1729 of 30 August 1973. In accordance with Article 19 of Law 30 of 1992, it retains its category of University and is based in the city of Santafé de Bogotá and sections in the cities of Medellín, Cali and Cartagena. The Cali campus was created on 24 August 1970, began academic work with the Bachelors of Law, Education and Accounting. The academic organization of the San Buenaventura Cali is made up of five faculties: Architecture, Art and Design; Economic and Administrative Sciences; Law and political science; Human and Social Sciences and Engineering, with 20 undergraduate programs, 21 face-to-face specializations, 4 virtual specializations, 24 masters, 5 PhD and 1 post-PhD, which guarantee their graduates and the general public to update and continue to advance in different fields of their professional development. |

| Existing Teaching and Learning Center | The Learning and Teaching Center (TLC) is a high-quality bet of San Buenaventura University as a fundamental element for the training processes and as a guarantor of high-quality strengths in higher education, promoting competitiveness, faculty development from research as the main source of generation and transfer of knowledge. From the infrastructure, there are multimedia rooms, sound laboratory and administrative office where the processes of innovation, teacher training and creation of didactic resources involving teachers and students of the educational community are centralized. |

| Link to TLC | Under construction |

| U4 | |

| Country | Colombia |

| Type of administration | Public |

| Number of Students | 16,562 |

| Number of Academics | 1309 |

| Origins and mission | The Universidad del Cauca is an autonomous university entity of the national order, created by the Decree of April 24, 1827, issued by the President of the Republic Francisco de Paula Santander at Popayán (Cauca) Mission The Universidad del Cauca is an institution of higher education, public, autonomous, of national order, created in the origins of the Republic of Colombia. The Universidad del Cauca, founded on its tradition and historical legacy, is a cultural project that has a vital and permanent commitment to social development through critical, responsible and creative education. The University forms people with ethical integrity, relevance and professional suitability, democrats committed to the welfare of society in harmony with the environment. The Universidad del Cauca generates and socializes science, technology, art and culture in teaching, research and social projection. |

| Existing Teaching and Learning Center | The Teaching and Learning Center of the Universidad del Cauca is linked to the Center for Quality Management and Institutional Accreditation. It is in charge of organizing the Diploma in Educational Innovations, diagnosis and teacher training and the articulation of student orientation services of the Vice Rector’s Office for Culture and Welfare. |

| Link to TLC | https://cgcai.unicauca.edu.co/innovacioneducativa/ (accessed on 20 December 2021). |

References

- Drüke, V. Übergangsgeschichten: Von Kafka, Widmer, Kästner, Gass, Ondaatje, Auster und anderen Verwandlungskünstlern; Athena-Verlag: Oberhausen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education: From Disruption to Recovery. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Singer, S.R. Learning and Teaching Centers: Hubs of Educational Reform. New Dir. High. Educ. 2002, 119, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, D.W.; Peters, J.; Olsen, T. Cocreating value in teaching and learning centers. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2013, 133, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.; Palmer, S.; Challis, D. Changing perspectives: Teaching and learning centres’ strategic contributions to academic development in Australian higher education. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2011, 16, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alam, G.M.; Forhad, M.A. Clustering Secondary Education and the Focus on Science: Impacts on Higher Education and the Job Market in Bangladesh. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2021, 65, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, M.; Klier, J.; Panier, F.; Schubert, J. Defining the Skills Citizens Will Need in the Future World of Work; McKinsey & Company: Minato, Tokyo, 2021; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/defining-the-skills-citizens-will-need-in-the-future-world-of-work (accessed on 22 October 2021).

- Blaschke, P.; Demel, J.; Kotorov, I. Innovation Performance of Small, Medium-Sized, and Large Enterprises in Czechia and Finland. ACC J. 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Asimiran, S. Online technology: Sustainable higher education or diploma disease for emerging society during emergency—Comparison between pre and during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 172, 121034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R. The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez Yàñez, Ó.; Aranda Càceres, R.; Corvalán Canessa, F.; González Rojas, L.; Ramos Torres, A. A teaching accompaniment and development model: Possibilities and challenges for teaching and learning centers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2019, 24, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, J.; Harding, A.G. A Logical Model for Curriculum Development. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 1986, 17, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R.W. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction; University of Chicago Press: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Tait, A. From Place to Virtual Space: Reconfiguring Student Support for Distance and E-Learning in the Digital Age. Open Prax. 2014, 6, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tait, A. Planning Student Support for Open and Distance Learning Open Learn. Open Learn. J. Open Distance e-Learn 2000, 15, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénard, F.; Roseveare, D. Fostering Quality Teaching in Higher Education: Policies and Practices; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012; p. 54. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/imhe/QT%20policies%20and%20practices.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Council of Australian Directors of Academic Development. Benchmarking Performance of Academic Development Units in Australian Universities. 2010. Available online: http://www.cadad.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Benchmarking_Report.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Moya, B.; Turra, H.; Chalmers, D. Developing and implementing a robust and flexible framework for the evaluation and impact of educational development in higher education in Chile. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2019, 24, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, D.; Holt, D.; Palmer, S. Teaching and learning centres: Towards maturation. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2009, 28, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, M.C.; Lohe, D.R.; Little, D. The Role of a Center for Teaching and Learning in a De-Centered Educational World. Chang. Mag. High. Learn. 2018, 50, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.; Holt, D.; Challis, D. Strategic leadership of Teaching and Learning Centres: From reality to ideal. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2011, 30, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hurney, C.A.; Brantmeier, E.J.; Good, M.R.; Harrison, D.; Meixner, C. The faculty learning outcome assessment framework. J. Fac. Dev. 2016, 30, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Genthon, M.M.K.E. Helping Teaching and Learning Centers Improve Teaching. In Accent on Improving College Teaching and Learning. National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning, 2400 SEB; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Behling, K.K.E. Collaborations between Centers for Teaching and Learning and Offices of Disability Services: Current Partnerships and Perceived Challenges. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 2017, 30, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brinthaupt, T.M.; Cruz, L.; Otto, S.; Pinter, M. A Framework for the Strategic Leveraging of Outside Resources to Enhance CTL Effectiveness. Improv. Acad. 2019, 38, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.C.; Lohe, D.R.; Pinder-Grover, T.; Ortquist-Ahrens, L. The Four Rs: Guiding CTLs with Responsiveness, Relationships, Resources, and Research. Improv. Acad. 2018, 37, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.M.; Bates, T.; Mota, J. What future(s) for distance education universities? Towards an open network-based approach. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. A Distancia 2019, 22, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Parvin, M. Can online higher education be an active agent for change?—Comparison of academic success and job-readiness before and during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 172, 121008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado Kloos, C.D.; Alario-Hoyos, C.; Morales, M.; Rocael, H.R.; Jerez, O.; Perez-Sanagustin, M.; Kotorov, I.; Fernandez, S.A.R.; Oliva-Cordova, L.M.; Solarte, M.; et al. PROF-XXI: Teaching and Learning Centers to Support the 21st Century Professor. In Proceedings of the 2021 World Engineering Education Forum/Global Engineering Deans Council, WEEF-GEDC 2021, Madrid, Spain, 15–18 November 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 448–455. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leech, N.L.; Anthony, J. Onwuegbuzie: A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual. Quant. 2009, 43, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapasia, N.; Paul, P.; Roy, A.; Saha, J.; Zaveri, A.; Mallick, R.; Barman, B.; Das, P.; Chouhan, P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal, India. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, F.; Munro, M. Why hasn’t technology disrupted academics’ teaching practices? Understanding resistance to change through the lens of activity theory. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberry, N.; McNaughton, S.; Billot, J.; Gaeta, H. Resituation or resistance? Higher education teachers’ adaptations to technological change. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2015, 24, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliger, I.; Ortiz-Rojas, M.; Pesántez-Cabrera, P.; Scheihing, E.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Muñoz-Merino, P.J.; Broos, T.; Whitelock-Wainwright, A.; Pérez-Sanagustín, M. Identifying needs for learning analytics adoption in Latin American universities: A mixed-methods approach. Internet High. Educ. 2020, 45, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viberg, O.; Hatakka, M.; Bälter, O.; Mavroudi, A. The current landscape of learning analytics in higher education. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, R.; Mahalakshmi, K.; Kumar, V.S.; Saravanakumar, A.R. E-Learning during lockdown of COVID-19 pandemic: A global perspective. Int. J. Control Autom. 2020, 13, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, L.; Gupta, T.; Shree, A. Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Roslan, S.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Leal Filho, W. Does GATS’Influence on Private University Sector’s Growth Ensure ESD or Develop City ‘Sustainability Crisis’—Policy Framework to Respond COP21. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Digital Skills & Jobs Platform 2021. Available online: https://digital-skills-jobs.europa.eu/en/inspiration/resources/digital-competence-test (accessed on 21 December 2021).

| University | 1st Phase of the Analysis | 2nd Phase of the Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative | Manager | Teaching/Academics | Total | Teaching and Learning Center Leader | |

| U1 (Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala) | 11 | 6 | 9 | 26 | 1 |

| U2 (Universidad de Galileo) | 8 | 2 | - | 10 | 1 |

| U3 (Universidad de San Buenaventura Cali) | 5 | 5 | 13 | 23 | 1 |

| U4 (Universidad del Cauca) | 1 | 1 | 22 | 24 | 1 |

| Total | 25 | 14 | 44 | 83 | 4 |

| Code | Description | Nature of the Data Collected | Original Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| [Competencies Questionnaire] | Questionnaire including 50 questions in which the participants have to value from 1 to 4 each of the competencies in the PROF-XXI framework in their institution | Quantitative | [Phase1-Activity1-CompetenciesQuestionnaire-EN]: https://osf.io/zdw3e/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [Phase1-Activity1-CompetenciesQuestionnaire-ES]: https://osf.io/ehr2t/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). |

| [Poster Initiatives Classification] | Collaborative digital poster created with Lucid.app for the participants to classify the different activities and initiatives conducted by their institution within the PROF-XXI framework competencies (See Appendix C). Participants had 20 min to add and discuss about the initiatives existing in their institution and associate them to a particular competence of the PROF-XXI framework. | Qualitative | [Phase1-Activity2-PosterInitiativeClassification]: https://osf.io/mfjtg/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [ANNEX 1] For accessing the original poster used during the sessions and the main contributions. |

| [Pre & Post Pandemic Lockdown Forms] | For to be completed by the TLC leaders. It includes two sections: (1) a table for listing the initiatives carried out for the institution to encourage the transformation and innovation for the teaching and learning processes, indicating whether they existed before the pandemic lockdown, whether they were maintained during the this period, whether they were originated with the pandemic lockdown, whether they are currently maintained in the institution; (2) a table for indicating, for each of the initiatives in the first table, to which dimension and competencies of the PROF-XXI framework they are associated. Only those responsible of the TLC of each institution completed this form. | Qualitative | [Phase2-PosCovidForm-EN]: https://osf.io/jxhc5/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [Phase2-PosCovidForm-ES]: https://osf.io/2trk5/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [Phase2-U1-PosCovidForm-ES]: https://osf.io/p6rk9/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [Phase2-U2-PosCovidForm-ES]: https://osf.io/5rac3/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [Phase2-U3-PosCovidForm-ES]: https://osf.io/g45ty/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). [Phase2-U4-PosCovidForm-ES]: https://osf.io/s684y/ (accessed on 21 December 2021). |

| Finding Code | Description | Partial Result Supporting the Finding |

|---|---|---|

| F1.1 | All staff in all institutions perceive that the Competence “A. Teachers’ support” is one of the most well-developed in their institution. They associated initiatives related to training the trainers (mostly for supporting the digital transition) and activities for teachers’ professional development. However, we noticed that, from all the roles analyzed (Administrative, Managers and Teaching/Academics staff), the managers were the ones giving the lowest values to this competence, while the Teaching/Academic staff in two universities (U1 and U4) evaluated them as the most well-developed. | [PR1.1] In all institutions, the Competence “A. Teachers’ support” was valued as one of the most developed (Table A3 in Appendix D). [PR1.3] Participants from U2 and U4 evaluated the Competence “A. Teachers’ support” as the most well-developed competence in the institution, and the Competence “E. Evidence-based practices” as the least developed (Table A3 in Appendix D). [PR1.4] In all institutions, the “Manager Staff” evaluates the Competence “A. Teachers’ support” with the lowest values, together with the “Teaching Staff” from U3. However, “Teaching/Academic Staff” from U1 and U4 evaluated it as the most well-developed. (Table A3 in Appendix D) [PR2.1] To the Competence “A. Teachers’ support”, institutions associated initiatives for training the teachers. The types of trainings vary in frequency and format depending on the institution, including courses, workshops, seminars, and diplomas (a set of courses with several ECTS credits). Most of trainings focus on learning about digital tools. Participants also associate with these competences related to teaching recognition, teaching evaluation and the share of good practices (Table A4 in Appendix D). |

| F1.2 | All staff in all institutions perceive that the Competence “B. Students’ support” is one of the least developed. Participants associated initiatives such as online courses, video-tutorials as well as academic support or on the Learning Management Systems employed by the university. Participants also recognize that, in some cases, the Competence “Students’ Support” is a bit poor. | Results in Table A3 in Appendix D. [PR2.2] To the Competence “B. Students’ support” participants associated initiatives such as online courses, video-tutorials as well as academic support or on the Learning Management Systems employed by the university. Participants also recognize that, in some cases, the Competence “Students’ Support” is a bit poor (Table A4 in Appendix D). |

| F1.3 | Despite the Competence “C. Leadership, Culture and Transformation” was not perceived as one of the most well-developed competencies; participants were able to associate some institutional activities, mainly related with the development of the “sense of belonging” to the institution, self-assessment activities, cross-institutional initiatives, and digital transformation. | Results in Table A3 in Appendix D. [PR2.3] To the Competence “C. Leadership, Culture and Transformation” participants associated activities such as (1) programs for developing the sense of belonging to the institution and its culture; (2) instances for self-evaluation, and instances for interacting with other institutions through research international programs. They also mentioned activities addressed to teaching/academics and administration staff related to the digital transformation of institutional processes (Table A5 in Appendix D). |

| F1.4 | Participants evaluated the Competence “D. Technology for Learning” as one of the most well-developed competencies and associated activities mainly related to training initiatives in the use of institutional platforms. Most of these initiatives were addressed to the teachers/academic staff, which indicates that these initiatives are closely related with Competence “A. Teachers’ support”. | Results in Table A3 in Appendix D. [PR2.4] To the Competence “D. Technology for Learning” participants associated initiatives such as training in the use of technological platforms (i.e., Moodle, Google Classroom) and tools (i.e., Google Suit) through online material, tutorials and courses (Table A5 in Appendix D). |

| F1.5 | The Competence “E. Evidence-based Practice” was perceived by all participants as the least developed competence in the institution. Participants associated to this competence initiatives related to the use of institutional data (Learning Analytics) for monitoring students’ and teachers’ progress and performance as well as activities related to the continuous improvement of the curriculum and benchmarking for studying initiatives in other institutions. | [PR1.2] All institutions, evaluated the Competence E “Evidence-based Practices” as the least developed. [PR2.5] To the competence “E. Evidence-based Practices”, participants associated initiatives related to the use of institutional data. The refer to initiatives for monitoring teachers and students’ performance. They also associated activities and initiatives related to the continuous curriculum improvement and benchmarking initiatives looking for other institutions practices as a reference. |

| F1.6 | The use of the model as a self-assessment mechanism also shows that we can distinguish between those institutions with the highest and lowest competencies. In this case study, U2 was one of the institutions with the highest competencies, which is one of the institutions with more experience in the digital transformation of their teaching and learning processes. | [PR1.5] Institution U2 has reported the highest values in terms of competence dimensions and compared to the other institutions. |

| Period | Finding Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Before the lockdown | F2.1 | Before the pandemic, most of the institutions counted with long training programs for teachers (diplomas of several weeks, for example). These programs were designed for training the teachers in different areas (digital tools, pedagogical support, etc.) and are still maintained after the pandemic lockdown. However, any institution create new training programs of this type during the pandemic lockdown. Only short training programs, such as workshops for showing specific tools or training teaching methodologies, were created during this period. All these initiatives are related to Competencies A (“Teachers’ Support”) and D (“Technology for Learning”) of the PROF-XXI framework. |

| F2.2 | Before the pandemic lockdown, the least developed competence from the PROF-XXI framework was the Competence “B. Students’ Support” (5 initiatives out of the 16 existing initiatives before the pandemic lockdown), but the initiatives related to this competence augmented during the pandemic lockdown (8 out of the 15 originated during this period). The most well-developed were “A. Teachers’ support” (12 out of 16) and “D. Technology for Learning”. | |

| During the lockdown | F2.3 | During the pandemic lockdown, institutions invested most of their efforts in developing the Competencies “A. Teachers’ support” (10 out of 15 initiatives were related to this competence) and “D. Technology for Learning” (12 out of 15 initiatives were related to this competence); investment in Competencies “E. Evidence-based Practices” decreased (from 6 initiatives related to this competence before the lockdown, only 3 were reported associated with this competence during this period). |

| F2.4 | The initiatives created by the TLC before the pandemic lockdown were related with the Competencies “A. Teachers’ Support” (12 of the 16 initiatives existing in this period for all universities) and “D. Technology for Learning” (13 of the 16 in total of this period for all universities). Whereas, during the pandemic lockdown, initiatives related to “B. Students’ Support” doubled (5 out of 16 before the lockdown and 6 out of 15 originated during this period). | |

| F2.5 | During the pandemic, all institutions created courses and materials (such as guidelines or video tutorials) for teachers and administrative staff that they facilitated through their online institutional systems. Some of the universities organized these materials in the form of online programs (i.e., U2). All universities related these initiatives to the competencies “A. Teachers’ Support”, “B. Students’ Support”, and “D. Technology for Learning”. Only U3 related the initiative created during the pandemic to all competencies of the framework. | |

| F2.6 | During the pandemic, U1 and U2 initiated activities for supporting teachers in the use of digital tools. Examples of these activities are coaching for teachers, personalized support, etc. These institutions explicitly mentioned that they created these initiatives for promoting innovating in online assessment practices. For example, they installed Proctoring tools for facilitating online assessment. U2 related some of these initiatives to the Competence “C. Culture and Transformation”. U1 also associated some of these initiatives with the Competencies “A. Teachers’ Support” and “D. Technology for Learning” of the PROF-XXI framework. | |

| Maintained after the lockdown | F2.7 | Three out of the four universities (except U3) maintain the activities that were originated for facing the pandemic lockdown. In U4, two of these initiatives are still under study to see if they are maintained or not. |

| F2.8 | After the pandemic lockdown, U1, U2, U4 reported they started to use the institutional platforms (i.e., VLE, Simulators, videoconferencing, etc.) in a more systematic way. These initiatives were usually related to the Competencies “D. Technology for Learning”, and to Competencies “A. Teachers’ Support” and “B. Students’ Support” for U2. | |

| F2.9 | After the pandemic lockdown, the number of initiatives of the TLC increased (from 16 existing before the pandemic to 27 maintained today). Although the number of initiatives associated to the different competencies increased, the universities still relate the majority of their initiatives to competencies “A. Teachers’ support” (15 out of the 27 initiatives are related to this competence) and “D. Technology for Learning” (18 out of the 27 initiatives are related to this competence), whereas Competencies “C. Leadership, Culture and Transformation” (9 out of 27) and “E. Evidence-based Practices” (9 out of 27) are still the least supported competencies. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Sanagustín, M.; Kotorov, I.; Teixeira, A.; Mansilla, F.; Broisin, J.; Alario-Hoyos, C.; Jerez, Ó.; Teixeira Pinto, M.d.C.; García, B.; Delgado Kloos, C.; et al. A Competency Framework for Teaching and Learning Innovation Centers for the 21st Century: Anticipating the Post-COVID-19 Age. Electronics 2022, 11, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11030413

Pérez-Sanagustín M, Kotorov I, Teixeira A, Mansilla F, Broisin J, Alario-Hoyos C, Jerez Ó, Teixeira Pinto MdC, García B, Delgado Kloos C, et al. A Competency Framework for Teaching and Learning Innovation Centers for the 21st Century: Anticipating the Post-COVID-19 Age. Electronics. 2022; 11(3):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11030413

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Sanagustín, Mar, Iouri Kotorov, António Teixeira, Fernanda Mansilla, Julien Broisin, Carlos Alario-Hoyos, Óscar Jerez, Maria do Carmo Teixeira Pinto, Boni García, Carlos Delgado Kloos, and et al. 2022. "A Competency Framework for Teaching and Learning Innovation Centers for the 21st Century: Anticipating the Post-COVID-19 Age" Electronics 11, no. 3: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11030413