Shared Care Practices in Community Addiction and Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study on the Experiences and Perspectives of Stakeholders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

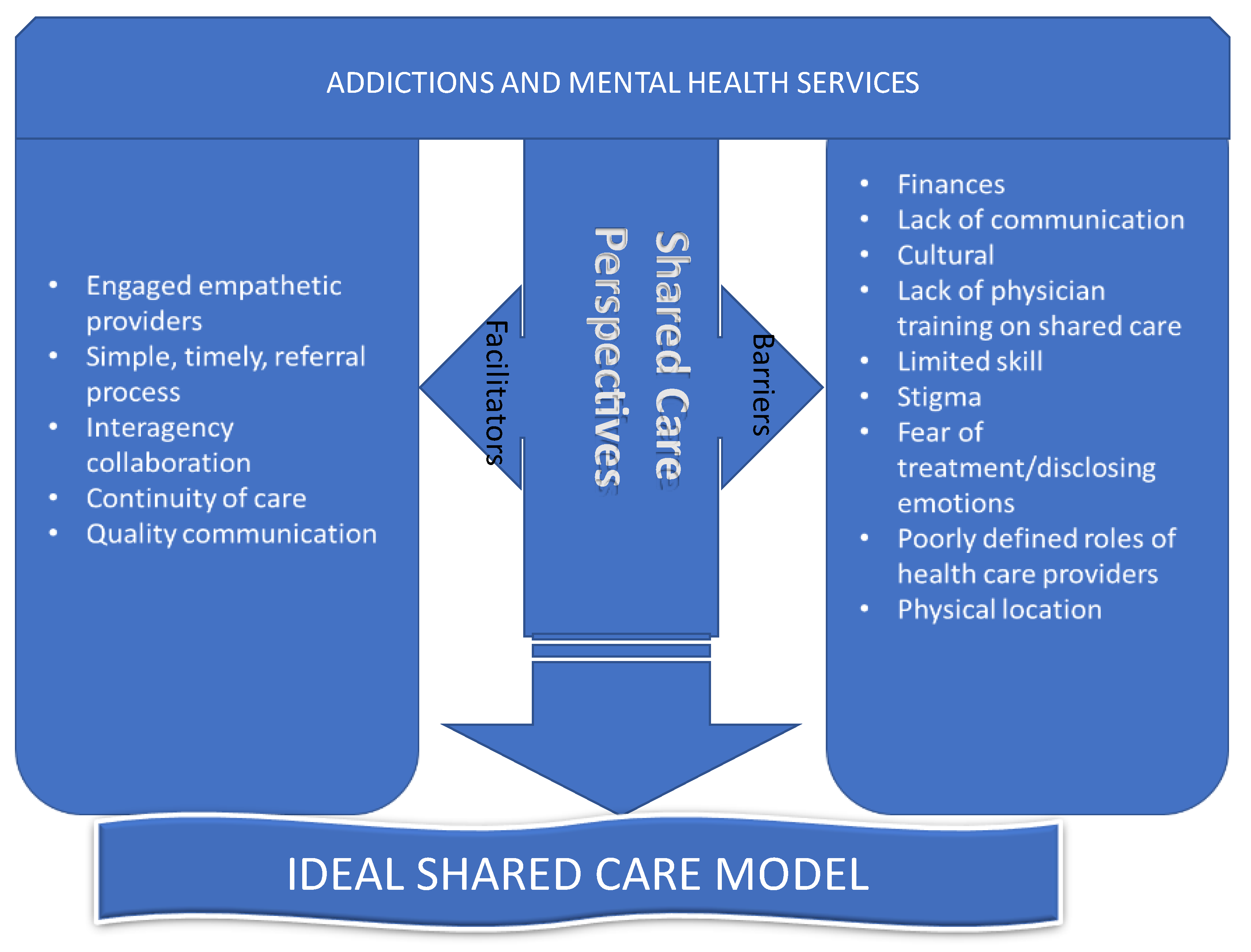

- What are stakeholders’ perceptions of what a shared care model within addiction and mental health should look like?

- What are stakeholders’ perceptions of barriers to the practice of shared care within addiction and mental health programs in the Edmonton zone?

Conceptual Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Defining Shared Care

3.1.1. Client-Centered Care: “The Patient Gets What They Need When They Need It”

AHS AMH Clinician: “I don’t know how many times we get calls from clients where they’re like, ‘Well this person told me this and this person told me this, and this person told me this.’”

AHS AMH Management: “Sometimes patients and families are treated like a hot potato, right? Well, they’re not severe enough for this program, so we’ll ask them to go here, but this program feels that their issues that they’re presenting with are more than what they can handle, and this poor family or client is kind of stuck in the middle, right.”

3.1.2. A Holistic Team Approach: “Having a Team Is Essential”

- Reduced load on overburdened psychiatrists and family physicians who work within a fee-for-service model that incentivizes seeing more patients in less time.

- The ability to use therapeutic approaches other than medication, potentially preventing the need for more psychiatric interventions.

- Especially in regards to social workers, case managers, and Independent Living Support (ILS) workers, helping clients navigate the mental health and social service systems and acting as a key connection point between other team members.

- Ongoing support and education around mental health and addictions for family physicians.

PCN Management: “It’s a flawed belief that just the doctor can fix […] I think it needs a whole team around that.”

Family Physician: “Yeah, we’re not mental health therapists, right? And many people, that’s what they need, they don’t need medication, they need CBT, they need support, they need … they can be kept from getting on medication if they have access to people that actually are really good at providing those kinds of treatments.”

PCN Management: “I think the shared care requires a really good understanding of the other providers. You’ve got to know where the overlap is, where the handoffs are appropriate, and so there’s a big part of that common understanding and maybe a lot of it with the family physicians and psychiatrists because they’re coming from the same discipline, but you start to throw in mental health therapists, your health consultants and RNs, social workers, you name them, […] we’re not sure where one’s role begins and the other ends, and I think that’s vital.”

3.1.3. Models of Shared Care: “There’s Different Ways of […] Doing Shared Care”

Psychiatrist: “So let’s say we have enough family doctors, then it’s going to be much easier for us to kind of see a patient, give an outline of say, give this medication, give that, and if it doesn’t work after say two three four weeks, try this, try that […]. If that doesn’t work, then the patient can be sent back to me.”

Family Physician: “Guidance, I totally agree. Support, or in my way of saying is guidance. Somebody on the phone, or somebody tell us exactly these are the steps to be followed so we don’t have to actually refer the patient down to the addiction center […] I think, as long as we have some guidance, we have some support from the right authorities, I think why not. I think we are great and in a much better position to do that than a third party”.

Psychiatrist: “But because mental health and addictions are longitudinal problems, I think there is a role to ensure that our part of the system stays involved in a longitudinal way. And then it doesn’t have to be a re-referral back in with, you know, a one month or two month long wait before they can access a program that had clearly benefitted them before.”

Family Physician: “It is doing the assessment, it’s seen by the psychiatrist, and it is being followed up on a regular basis until the patient is now stable enough to be discharged back to your practice.”

PCN Management: “Addiction or mental health is an ideal problem for the community and family physicians because it’s long-term, and you need that team, so no different than having the diabetic in a practice forever if you look at it, sure, you want to get them to be not addicted and all that, but it is chronic, and so it fits nicely in family medicine because there’s already a long-term support in place if the skills are there.”

Psychiatrist: “I think [family physicians] should be very actively involved in follow-up […] I think with collaboration and help from us, I think they should be following up with patients. I think a lot of family doctors are reluctant to do so, they’re quite happy for us to take over, but I think we really need to push and explore more collaboration with primary care in relation to follow up with patients.”

3.2. Obstacles to Shared Care

3.2.1. Fragmented Communication: “Like an Estranged Marriage”

Family Physician: “To me it feels a bit vacuous because I know they’re out there, I know my patients are sometimes having contact with the services, and I feel like we don’t have any kind of back and forth communication about what that is, and we’re not a team working for this patient’s best interest together, that it’s kind of just these two disparate interactions with no coordination.”

Family Doctor: “If you send someone to a private psychiatrist, you’ll get a consult letter back but often not follow up visits or maintenance visits or anything like that.”

PCN Therapist: “I don’t know if it’s everywhere, but most of the time the therapist at [clinic name] or [clinic name] will send the first letter once they’ve connected with the family doctor’s patient to the family doctor saying “I’ve seen this person, this is what we’re going to work on,” and then they never hear from them again.”

3.2.2. Family Physician Barriers: “Are the Doctors Comfortable Discussing Addictions and Mental Health Concerns?”

Client: “I wouldn’t feel comfortable talking it over with my family doctor, no.”

AHS AMH Management: “I still think stigma is a big, big one that from a patient’s perspective that I would much rather compartmentalize my own care. […] what you’re telling me here is no, no that’s wrong, that the psychologist should be sharing my horrible thoughts with my family doctor that takes care of my kid, treats their foot fungus, and now you’re going to be talking about that? I think these are confidentiality and disclosure, and it’s tied with a bit of stigma and personal baggage.”

Family Physician: “I know I have a lot of colleagues who don’t want it to come up because they don’t feel like they have solutions or things that they can do if these sorts of issues arise, and so they’ll like almost deliberately skirt the issue and like, “let’s deal with your knee! Please don’t cry!” So that they don’t have to deal with this when they have no solutions or no ideas about what to do if a mental health concern comes up.”

PCN Therapist: “We have a lot of walk-in clinics and we get the impression on the mental health team that if somebody sheds one tear it’s an automatic referral.”

Psychiatrist: “I think the management piece tends to be harder given the model that a lot of the family physicians are forced to practice under. I don’t think it’s a lack of capability, but I think it’s literally how what else they’re expected to do in their time that becomes the challenge and so this is the feedback I get from a lot of colleagues that might do family medicine.”

AHS AMH Management: “Physicians, I mean they’re paid fee-for-service so they need to, they want to see as many … they’re driven by the number of clients they see and the workload.”

PCN Management: “The literature says 25–40% of all visits to family physicians involve a mental health complaint, so they must be handling that. I don’t think they can turn from it and run from it, but again, some find it a rewarding part of their practice and others prefer to have help. […] But I think the degree or the complexity of the mental health will decide whether it stays in the practice or it gets referred out, not different from cardiology or orthopedics or…”

Psychiatrist: “I think, in fairness to family docs, we see in the PCN that they come looking for help, but I think this should be a targeted area to deal with addictions. […] I see it reflected in what comes at the college level and how the college is trying to change attitudes, etc., but I also see it in my own experience in primary care.”

3.2.3. Lack of Addictions and Mental Health Capacity: “There Are Never Enough Psychiatrists”

Psychiatrist: “Well if they want that, then they’ll have to wait more, though. If you want that, then instead of seeing me within two weeks, or within a month, it’ll be six months to a year. You know, that’s private practice. That’s then a six month or a year wait list.”

Family Physician: “In fact when people in other places have tried to remove that role from family physicians and put it all onto psychiatrists, the system’s just fallen completely flat because there are never enough psychiatrists, they can never spend enough time with all the patients, we cannot have that, you know, this isn’t something, ‘Oh, you’ve got an addiction, oh my god, go away and see a psychiatrist.’ It cannot be like that.”

3.2.4. Concerns with Information-Sharing: “Confidentiality Is a Problem”

Client: “One thing I’d adjust on what I’ve said is just that maybe if it’s something that’s really confidential, really personal, maybe something like that you wouldn’t want shared between all three [therapist, psychiatrist, and family doctor]”.

AHS AMH Management: “I think that’s a real fundamental issue about confidentiality and how this information is going to be available and how is it recorded […] you know, because stigma is real. There’s a reason why people are worried about others knowing about their issues and that kind of thing, so how do we circumvent that so that there could be collaboration around the care without exposing the client?”

Client: “Does shared care mean lack of individual responsibility?”

AHS AMH Clinician: “If you have so many different doctors trying to manage the same thing in different ways all at once, that’s risky.”

PCN Management: “I think the other key piece is you often hear, “Well at the end of the day I’m responsible so I’ll make the decision,” and even though it’s like, my license is on the line, or it’s—so I think there’s got to be, shared care is who’s the shared decision maker? Right? And that also has to be enabled through a whole bunch of other things. But you can only share care if you’re sharing decisions.”

3.2.5. Practitioner Buy-In: “This Is How Things Are Done, and We’ve Always Done It This Way”

AHS AMH Clinician: “If you believe in shared care as a practice […] so physician buy-in, like your primary care provider buy-in, like really enables that.”

AHS AMH Management: “I think culture as well prevents it. There’s a whole lot of “this is how things are done, and we’ve always done it this way.” […] Absolutely culture for sure. […] There’d be some big change management.”

3.3. Suggestions to Enable Shared Care

3.3.1. Electronic Medical Record (EMR) Communication: “That Online, Fluid Conversation”

AHS AMH Clinicians: “It would be nice if the primary care and all GPs were also on the same EMR as us, because they are so disconnected. They need us to be like reaching out constantly which takes effort and time, then they aren’t available, they aren’t there, they’re on vacation, the secretary doesn’t know, they don’t know anything about this client, there’s nothing in the file.”

AHS AMH Management: “And to me the biggest thing that prevents or disenables is getting rid of those silos, getting rid of the differences, like if you’re going to have primary care networks, then only bring them in, we should be on the same EMRs, we should be in the same locations, we should have hopefully letters of understanding that we can communicate freely or whatever’s required. All those barriers should be gone.”

PCN Management: “I’m looking at a variety of ways of doing that, of, right, not just old school like consultation letter faxed somewhere, into the oblivion, right, and then there’s an expectation that ginormous pile of other consultation letters that arrive at a physician’s desk every day, there’s a way to have that online, fluid conversation.”

3.3.2. Relationship Building and Collaboration: “Picking Up the Phone”

AHS AMH Clinicians: “I don’t think our clinic has an overall approach, but it’s all relationship based, based on who the therapist is, so I know from my own practice, I just have certain GPs and PCNs that I’ve built a relationship with over time, that we work beautifully together, we consult, we meet, if we’re trying to coordinate treatment or some kind of care, they’ll facilitate the medical component, and managing the withdrawal in the community without having to go to detox and all of those pieces, and so we do work in partnership, but it’s not an AHS partnership, it’s just an individual relationship based on […] my clients and the community”.

PCN Therapist: “But we have that relationship where we can phone up and say hey what’s going on like I need a consult or I need what’s happened last time with the psychiatrist and they’ll send it immediately.”

Family doctor: “What’s missing right now, so defining who your team is and then having the frequent ability to communicate with the team and chat with your mental health worker, your social worker, and your psychiatrist […] but that communication is for me what’s really lacking in all of this is that ability to keep going back and redefining the issue and then determining what the plan is going to be depending on what we’ve seen going on.”

3.3.3. Physical Co-Location: “You’re in the Same Space”

AHS AMH Management: “[I]f you co-locate resources and include the patient in those conversations, most of these shared care principles would be achieved. It sounds easy, I know it’s not.”

Family Doctor: “I get more of that through my primary care medical home with my embedded social workers or my embedded therapist because we will talk back and forth and say, ‘okay you guys are working on this, this is the therapy piece you’re doing, this is what we’re going with medications, I’m going to reinforce your therapy strategies every time the patient comes in.’ And as long as I know what they are then I can help reinforce them and redirect them to your strategies and okay carry on. And I feel like that’s a lot more cohesive model for managing those patients in a collaborative way when you can actually have the discourse about it.”

PCN Management: “But I think the comfort level has certainly changed with providers, clinicians that are right in the family office, there’s lots of discussions or hallway conversations around specific patient issues so now their confidence level or perhaps their knowledge or resources has now increased because there’s that constant communication happening on a daily basis for them to be aware of what to do in the moment with those patients.”

3.3.4. Referrals and Service Information: “More Bridging […] so They’re Aware of the Services”

Family Doctor: “For me too another aspect is kind of a central access searchable form of what programs are available. So, I mean in my perfect world, I’d be able to go on [to a] central system, enter the words like depression, addictions, past trauma history and have some list of possibly appropriate programs show up where it’s like this might be a good match for your patient.”

AHS AMH Clinician: “And I think that that’s the other thing that’s really important is to not burden GPs with referrals and all sorts of paperwork that they need to do.”

AHS AMH Management: “But then we get a lot of referrals which are inappropriate because they’re not complex, and then it’s so our relationship is a lot of educating, so when we do get access to a GP or a PCN then we spend a lot of time trying to educate them in terms of appropriateness”.

AHS AMH Management: “But any mental health therapist that can identify a mental health or addiction needs to be able to refer to a psychiatrist.”

AHS AMH Management: “Yeah I think a reciprocal relationship where you can refer to us and we can refer back, or we can take on the care for a bit and then you know perhaps once they’re stabilized we can return them back the physician care with of course any support as needed”.

4. Discussion

- Integrated illness management and recovery (I-IMR), where an I-IMR specialist provided an eight-week curriculum, containing two modules for medical and psychiatric health, which were tailored according to the individual needs [50].

- The Primary Care Access Referral and Evaluation (PCARE), which was introduced to people with comorbid severe mental illness, where nursing care managers played the pivotal role in patient management care, through advocacy, information providing and motivational interviewing [51].

- Life goal collaborative care (LGCC), where enhanced self-management control of risky behaviors in bipolar patients resulted in less manic symptoms and lower blood pressure among the intervention group who were offered four weeks of mental health specialist support followed by twelve months of care manager support [52].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henderson, S. The National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being in Australia: Impact on policy. Can. J. Psychiatry 2002, 47, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kates, N.; Arroll, B.; Currie, E.; Hanlon, C.; Gask, L.; Klasen, H.; Meadows, G.; Rukundo, G.; Sunderji, N.; Ruud, T.; et al. Improving collaboration between primary care and mental health services. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 20, 748–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings: Version 1.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. vii, p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Chwastiak, L.; Vanderlip, E.; Katon, W. Treating complexity: Collaborative care for multiple chronic conditions. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, T.; Goldman, S.; Marcus, M. Reversed Shared Care in Mental Health: Bringing Primary Physical Health Care to Psychiatric Patients. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2013, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Dekker, J.M.; Wood, D.; Kahl, K.G.; Holt, R.I.; Moller, H.J. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meyer, F.; Peteet, J.; Joseph, R. Models of care for co-occurring mental and medical disorders. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2009, 17, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulman, D.M.; Asch, S.M.; Martins, S.B.; Kerr, E.A.; Hoffman, B.B.; Goldstein, M.K. Quality of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: The role of comorbidity interrelatedness. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, L.; Shaw, J.; Sethi, S.; Kirsten, L.; Beatty, L.; Mitchell, G.; Kissane, D.; Kelly, B.; Turner, J. Barriers and facilitators to community-based psycho-oncology services: A qualitative study of health professionals’ attitudes to the feasibility and acceptability of a shared care model. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 1862–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, M.; Drummond, N.; Grimshaw, J. A taxonomy of shared care for chronic disease. J. Public Health Med. 1994, 16, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, R.; Creer, R.; Jackson, J.; Ehrlich, D.; Tompkin, A.; Bowen, M.; Tromans, C. Scope of practice of optometrists working in the UK Hospital Eye Service: A national survey. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2016, 36, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchings, R. Shared care for glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1995, 79, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Koolwijk, L.M.; Uiterwaal, C.S.; van der Laag, J.; Hoekstra, J.H.; Gulmans, V.A.; van der Ent, C.K. Treatment of children with cystic fibrosis: Central, local or both? Acta Paediatr. 2002, 91, 972–977, discussion 894–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doull, I. Shared care—Is it worth it for the patient? J. R. Soc. Med. 2012, 105 (Suppl. 2), 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, L.; Lowe, R. 122 Ensuring the delivery of excellent care, close to home-developing a teleconference ‘Vitual MDT’ for the management of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia across multiple shared care centres. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, A48–A49. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, R.; de Korne, D.F.; Wong, T.Y.; Hwee, D.T.T.; Chiang, P.P.; Wong, E.; Chakraborty, B.; Lamoureux, E.L. Shared Care for Patients with Diabetes at Risk of Retinopathy: A Feasibility Trial. Int. J. Integr. Care 2019, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branger, P.J.; van’t Hooft, A.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Moorman, P.W.; van Bemmel, J.H. Shared care for diabetes: Supporting communication between primary and secondary care. Int. J. Med. Inform. 1999, 53, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, N.; Craven, M.; Bishop, J.; Clinton, T.; Kraftcheck, D.; LeClair, K.; Leverette, J.; Nash, L.; Turner, T. Shared mental health care in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 1997, 42, i–xii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.-A. Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative. Advancing the Agenda for Collaborative Mental Health Care; Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2005; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Changing Directions, Changing Lives the Mental Health Strategy for Canada; Mental Health Commission of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Unutzer, J. Closing the False Divide: Sustainable Approaches to Integrating Mental Health Services into Primary Care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durbin, A.; Durbin, J.; Hensel, J.M.; Deber, R. Barriers and Enablers to Integrating Mental Health into Primary Care: A Policy Analysis. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 43, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion, A.; Sunderji, N.; Jansz, G.; Ghavam-Rassoul, A. Understanding integrated mental health care in “real-world” primary care settings: What matters to health care providers and clients for evaluation and improvement? Fam. Syst. Health 2017, 35, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Huxley, P.; Baker, C.; White, J.; Madge, S.; Onyett, S.; Gould, N. The social care component of multidisciplinary mental health teams: A review and national survey. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2012, 17 (Suppl. 2), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imenda, S. Is There a Conceptual Difference between Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks? J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 38, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeck, G.; Davidsen, A.S.; Kousgaard, M.B. Enablers and barriers to implementing collaborative care for anxiety and depression: A systematic qualitative review. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samy, D.C.; Hall, P.; Rounsevell, J.; Carr, R. ‘Shared Care Shared Dream’: Model of shared care in rural Australia between mental health services and general practitioners. Aust. J. Rural Health 2007, 15, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goossen, R.B.; Staley, J.D.; Pearson, M. Does the introduction of shared care therapists in primary health care impact clients’ mental health symptoms and functioning? Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2008, 27, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.J.; Perkins, D.A.; Fuller, J.D.; Parker, S.M. Shared care in mental illness: A rapid review to inform implementation. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2011, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lester, H.; Tritter, J.Q.; England, E. Satisfaction with primary care: The perspectives of people with schizophrenia. Fam. Pract. 2003, 20, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shea, M.; Wong, Y.J.; Nguyen, K.K.; Gonzalez, P.D. College students’ barriers to seeking mental health counseling: Scale development and psychometric evaluation. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, K.; McGregor, B.; Thandi, P.; Fresh, E.; Sheats, K.; Belton, A.; Mattox, G.; Satcher, D. Toward culturally centered integrative care for addressing mental health disparities among ethnic minorities. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunderji, N.; Ion, A.; Huynh, D.; Benassi, P.; Ghavam-Rassoul, A.; Carvalhal, A. Advancing Integrated Care through Psychiatric Workforce Development: A Systematic Review of Educational Interventions to Train Psychiatrists in Integrated Care. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badu, E.; O’Brien, A.P.; Mitchell, R. An integrative review of potential enablers and barriers to accessing mental health services in Ghana. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. Perceived barriers to mental health service use among individuals with mental disorders in the Canadian general population. Med. Care 2006, 44, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlatte, O.; Salway, T.; Rice, S.; Oliffe, J.L.; Rich, A.J.; Knight, R.; Morgan, J.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S. Perceived Barriers to Mental Health Services Among Canadian Sexual and Gender Minorities with Depression and at Risk of Suicide. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canada, S. Census Profile, 2016 Census, Edmonton [Census Metropolitan Area], Alberta and Alberta [Province] (Table). 2016. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CMACA&Code1=835&Geo2=PR&Code2=48&Data=Count&SearchText=edmonton&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1 (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Gray, D. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide to Textual, Media and Virtual Techniques; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Tanenbaum, S.J. What is Patient-Centered Care? A Typology of Models and Missions. Health Care Anal. 2015, 23, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Coombes, I.; McMillan, S.; Wheeler, A.J. Clozapine and shared care: The consumer experience. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, M.; Geiger, F.; Wehkamp, K.; Rueffer, J.U.; Kuch, C.; Sundmacher, L.; Skjelbakken, T.; Rummer, A.; Novelli, A.; Debrouwere, M.; et al. Making shared decision-making (SDM) a reality: Protocol of a large-scale long-term SDM implementation programme at a Northern German University Hospital. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoul, G.; Clayman, M.L. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 60, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosire, E.N.; Mendenhall, E.; Norris, S.A.; Goudge, J. Patient-Centred Care for Patients with Diabetes and HIV at a Public Tertiary Hospital in South Africa: An Ethnographic Study. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.E.; Von Korff, M.; Lin, E.H.; Ludman, E.; Ciechanowski, P.S. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradford, D.W.; Cunningham, N.T.; Slubicki, M.N.; McDuffie, J.R.; Kilbourne, A.M.; Nagi, A.; Williams, J.W., Jr. An evidence synthesis of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e754–e764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Katon, W.J.; Lin, E.H.; Von Korff, M.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.J.; Young, B.; Peterson, D.; Rutter, C.M.; McGregor, M.; McCulloch, D. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katon, W.; Russo, J.; Lin, E.H.; Schmittdiel, J.; Ciechanowski, P.; Ludman, E.; Peterson, D.; Young, B.; Von Korff, M. Cost-effectiveness of a multicondition collaborative care intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raney, L.E.; American Psychiatric Association. Integrated Care: Working at the Interface of Primary Care and Behavioral Health, 1st ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 2015; p. xvii, p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, S.J.; Pratt, S.I.; Mueser, K.T.; Naslund, J.A.; Wolfe, R.S.; Santos, M.; Xie, H.; Riera, E.G. Integrated IMR for psychiatric and general medical illness for adults aged 50 or older with serious mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Druss, B.G.; von Esenwein, S.A.; Compton, M.T.; Rask, K.J.; Zhao, L.; Parker, R.M. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: The Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Goodrich, D.E.; Lai, Z.; Post, E.P.; Schumacher, K.; Nord, K.M.; Bramlet, M.; Chermack, S.; Bialy, D.; Bauer, M.S. Randomized controlled trial to assess reduction of cardiovascular disease risk in patients with bipolar disorder: The Self-Management Addressing Heart Risk Trial (SMAHRT). J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e655–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, K.W.; Ng, P.; Kwok, T.; Cheng, D. The effects of holistic health group interventions on improving the cognitive ability of persons with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, A.F.; Mangione, C.M.; Saliba, D.; Sarkisian, C.A.; California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders with Diabetes. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McClanahan, K.K.; Huff, M.B.; Omar, H.A. Holistic health: Does it really include mental health? Sci. World J. 2006, 6, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, M.; Dalton, J.; Harden, M.; Street, A.; Parker, G.; Eastwood, A. Integrated Care to Address the Physical Health Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness: A Mapping Review of the Recent Evidence on Barriers, Facilitators and Evaluations. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockman, P.; Salach, L.; Gotlib, D.; Cord, M.; Turner, T. Shared mental health care. Model for supporting and mentoring family physicians. Can. Fam. Physician 2004, 50, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Yagi, F.; Yoshizumi, A. Application of Level of Care Utilization System for Psychiatric and Addiction Services (LOCUS) to psychiatric practice in Japan: A preliminary assessment of validity and sensitivity to change. Community Ment. Health J. 2013, 49, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, W.; George, C.; Thompson, K. Level of care utilization system for psychiatric and addiction services (LOCUS): A preliminary assessment of reliability and validity. Community Ment. Health J. 1999, 35, 545–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eboreime, E.A.; Nxumalo, N.; Ramaswamy, R.; Ibisomi, L.; Ihebuzor, N.; Eyles, J. Effectiveness of the Diagnose-Intervene- Verify-Adjust (DIVA) model for integrated primary healthcare planning and performance improvement: An embedded mixed methods evaluation in Kaduna state, Nigeria. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, P.J.; Winter, S.C. Politicians, managers, and street-level bureaucrats: Influences on policy implementation. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 19, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Foster, M.; Weaver, J.; Shalaby, R.; Eboreime, E.; Poong, K.; Gusnowski, A.; Snaterse, M.; Surood, S.; Urichuk, L.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Shared Care Practices in Community Addiction and Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study on the Experiences and Perspectives of Stakeholders. Healthcare 2022, 10, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050831

Foster M, Weaver J, Shalaby R, Eboreime E, Poong K, Gusnowski A, Snaterse M, Surood S, Urichuk L, Agyapong VIO. Shared Care Practices in Community Addiction and Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study on the Experiences and Perspectives of Stakeholders. Healthcare. 2022; 10(5):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050831

Chicago/Turabian StyleFoster, Michele, Julia Weaver, Reham Shalaby, Ejemai Eboreime, Kimberly Poong, April Gusnowski, Mark Snaterse, Shireen Surood, Liana Urichuk, and Vincent I. O. Agyapong. 2022. "Shared Care Practices in Community Addiction and Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study on the Experiences and Perspectives of Stakeholders" Healthcare 10, no. 5: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050831

APA StyleFoster, M., Weaver, J., Shalaby, R., Eboreime, E., Poong, K., Gusnowski, A., Snaterse, M., Surood, S., Urichuk, L., & Agyapong, V. I. O. (2022). Shared Care Practices in Community Addiction and Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study on the Experiences and Perspectives of Stakeholders. Healthcare, 10(5), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050831