Marine Rare Actinomycetes: A Promising Source of Structurally Diverse and Unique Novel Natural Products

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Isolation Methods for Marine Rare Actinomycetes

2.1. Basic Approaches for Isolation Media for Marine Rare Actinomycetes

2.2. Pretreatment of Marine Samples

3. Marine Habitats: The Largest Reservoir for Rare Actinomycetes

3.1. Rare Actinomycetes from Marine Sediments, Seawater, Eukaryotic Hosts and Mangroves

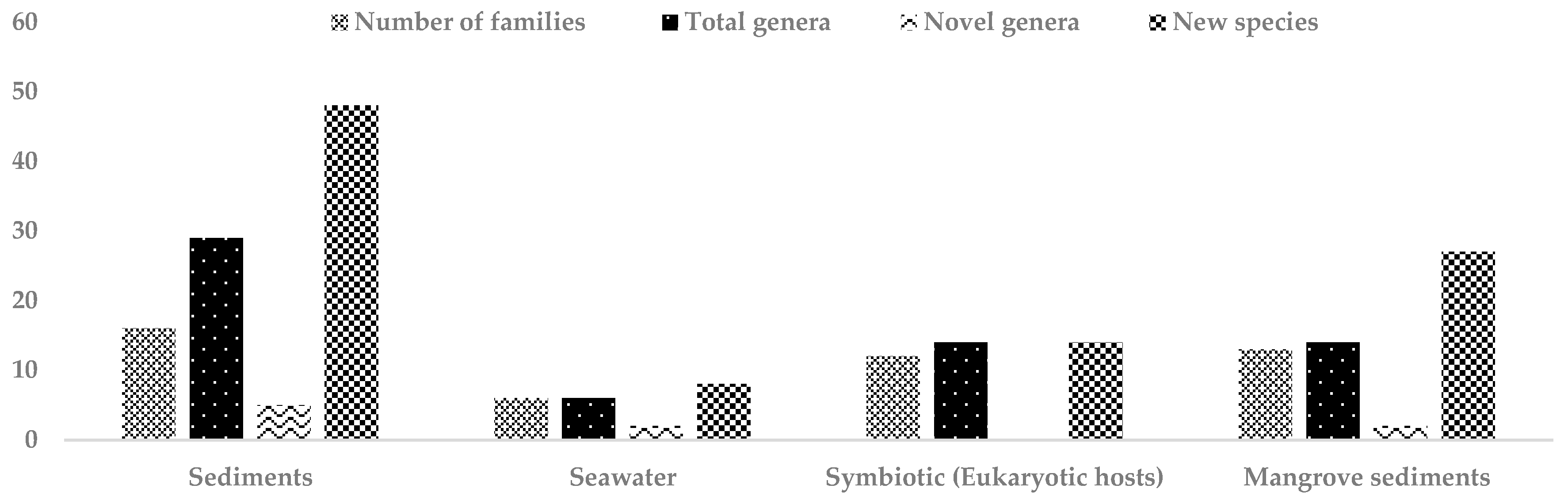

3.2. Marine Rare Actinomycetes Diversity: A Decade of Experience (2007–2017)

4. Actinomycetes as Sources of Antibiotics

4.1. Rare Actinomycetes: A Target for Future Drugs

4.2. Marine Rare Actinomycetes Is a Source of Antibiotics

4.3. Novel/New Compounds from Marine Rare Actinomycetes between mid-2013 and 2017

4.4. Genome Mining of Marine Rare Actinomycetes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, S.N.; Khan, A.U. Breaking the spell: Combating multidrug resistant ‘Superbugs’. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challinor, V.L.; Bode, H.B. Bioactive natural products from novel microbial sources. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1354, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdy, J. Thoughts and facts about antibiotics: Where we are now and where we are heading. J. Antibiot. 2012, 65, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locey, K.J.; Lennon, J.T. Scaling laws predict global microbial diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 5970–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, E.A.; Vatsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Klenk, H.-P.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dhakal, D.; Pokhrel, A.R.; Shrestha, B.; Sohng, J.K. Marine rare actinobacteria: Isolation, characterization, and strategies for harnessing bioactive compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Aalbersberg, W. Culturable rare actinomycetes: Diversity, isolation and marine natural product discovery. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9291–9321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Azman, A.S.; Othman, I.; Velu, S.S.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H. Mangrove rare actinobacteria: Taxonomy, natural compound and discovery of bioactivity. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arul Jose, P.; Jha, B. Intertidal marine sediment harbours Actinobacteria with promising bioactive and biosynthetic potential. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Dai, X.; Liu, L.; Xi, L.; Wang, J.; Song, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Diversity, biogeography, and biodegradation potential of actinobacteria in the deep-sea sediments along the southwest indian ridge. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claverías, F.P.; Undabarrena, A.; González, M.; Seeger, M.; Cámara, B. Culturable diversity and antimicrobial activity of Actinobacteria from marine sediments in Valparaíso bay, Chile. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hames-Kocabas, E.E.; Uzel, A. Isolation strategies of marine-derived actinomycetes from sponge and sediment samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 2012, 88, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, L.A.; Fenical, W.; Jensen, P.R.; Kauffman, C.A.; Mincer, T.J.; Ward, A.C.; Bull, A.T.; Goodfellow, M. Salinispora arenicola gen. nov., sp. nov. and Salinispora tropica sp. nov., obligate marine actinomycetes belonging to the family Micromonosporaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotchev, S.B. Marine actinomycetes as an emerging resource for the drug development pipelines. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 158, 68–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overmann, J.; Lepleux, C. Marine Bacteria and Archaea: Diversity, adaptations, and culturability. In The Marine Microbiome: An Untapped Source of Biodiversity and Biotechnological Potential; Stal, L.J., Cretoiu, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schwager, E.; Luo, C.; Huttenhower, C.; Morgan, X.C. Sequencing and other tools for studying microbial communities: Genomics and “meta’omic” tools are enabling us to explore the microbiome from three complementary perspectives—Taxonomic, functional and ecological. Microbe 2015, 10, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, T.; Lewis, K.; Epstein, S.S. Isolating “uncultivable” microorganisms in pure culture in a simulated natural environment. Science 2002, 296, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengler, K.; Toledo, G.; Rappé, M.; Elkins, J.; Mathur, E.J.; Short, J.M.; Keller, M. Cultivating the uncultured. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 15681–15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartoukian, S.R.; Palmer, R.M.; Wade, W.G. Strategies for culture of ‘unculturable’ bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 309, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.J. Growing unculturable bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4151–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamagata, Y. Keys to cultivating uncultured microbes: Elaborate enrichment strategies and resuscitation of dormant cells. Microbes Environ. 2015, 30, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Jiang, C. Isolation and cultivation methods of Actinobacteria. In Actinobacteria-Basics and Biotechnological Applications; Dhanasekaran, D., Jiang, Y., Eds.; InTech: London, UK, 2016; Chapter 2; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Azman, A.S.; Zainal, N.; Mutalib, N.A.; Yin, W.F.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H. Monashia flava gen. nov., sp. nov., an actinobacterium of the family Intrasporangiaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.; Wei, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Gillerman, L. Halopolyspora alba gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2775–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Sediminivirga luteola gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Brevibacteriaceae, isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1494–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, X. Haloactinomyces albus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from the dead sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Q.; Xing, S.S.; Yuan, W.D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Sun, Q.G.; Lin, X.Z.; Bao, S.X. Nocardiopsis mangrovei sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 107, 1541–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, P.R.; Gontang, E.; Mafnas, C.; Mincer, T.J.; Fenical, W. Culturable marine actinomycete diversity from tropical pacific ocean sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvin, J.; Shanmughapriya, S.; Gandhimathi, R.; Kiran, G.S.; Ravji, T.R.; Natarajaseenivasan, K.; Hema, T.A. Optimization and production of novel antimicrobial agents from sponge associated marine actinomycetes Nocardiopsis dassonvillei MAD08. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 83, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, L.A.; Stach, J.E.M.; Pathom-aree, W.; Ward, A.C.; Bull, A.T.; Goodfellow, M. Diversity of cultivable actinobacteria in geographically widespread marine Sediments. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2005, 87, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, T.J.; Fenical, W.; Jensen, P.R. Cultured and culture-independent diversity within the obligate marine actinomycete genus Salinispora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 7019–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontang, E.A.; Fenical, W.; Jensen, P.R. Phylogenetic diversity of Gram-positive bacteria cultured from marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 3272–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Baker, P.; Piper, C.; Cotter, P.D.; Walsh, M.; Mooij, M.J.; Bourke, M.B.; Rea, M.C.; O’Connor, P.M.; Ross, R.P.; et al. Isolation and analysis of bacteria with antimicrobial activities from the marine sponge Haliclona simulans collected from Irish waters. Mar. Biotechnol. 2009, 11, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, L.A.; Frangoso-Yanez, D.; Perez-Garcia, A.; Rosellon-Druker, J.; Quintana, E. Actinobacterial diversity from marine sediments collected in Mexico. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 95, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, G. Nocardioides flavus sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5275–5280. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, G.I.; Cho, Y.; Cho, B.C. Pontimonas salivibrio gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Microbacteriaceae isolated from a seawater reservoir of a solar saltern. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2124–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D. Tamlicoccus marinus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1951–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Menezes, C.B.; Tonin, M.F.; Silva, L.J.; de Souza, W.R.; Parma, M.; de Melo, I.S.; Zucchi, T.D.; Destéfano, S.A.; Fantinatti-Garboggini, F. Marmoricola aquaticus sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from a marine sponge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2286–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso de Menezes, C.B.; Afonso, R.S.; Souza, W.R.; Parma, M.; Melo, I.S.; Zucchi, T.D.; Fantinatti-Garboggini, F. Williamsia spongiae sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from the marine sponge Amphimedon viridis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1260–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, D.T.; Silva, F.S.P.D.; Silva, L.J.D.; Crevelin, E.J.; Moraes, L.A.B.; Zucchi, T.D.; Melo, I.S. Saccharopolyspora spongiae sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from the marine sponge Scopalina ruetzleri (Wiedenmayer, 1977). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2019–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaprasad, E.V.; Sasikala, C.; Ramana, C.V. Ornithinimicrobium algicola sp. nov., a marine actinobacterium isolated from the green alga of the genus Ulva. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 4627–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongsopitanun, W.; Kudo, T.; Ohkuma, M.; Pittayakhajonwut, P.; Suwanborirux, K.; Tanasupawat, S. Micromonospora sediminis sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 3235–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Wang, H.F.; Xiong, Z.J.; Tian, X.P.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.M.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.J. Mariniluteicoccus flavus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Propionibacteriaceae, isolated from a deep-sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathom-aree, W.; Stach, J.E.M.; Ward, A.C.; Horikoshi, K.; Bull, A.T.; Goodfellow, M. Diversity of actinomycetes isolated from Challenger deep sediment (10,898 m) from the Mariana Trench. Extremophiles 2006, 10, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, M.; Colwell, R.R.; Hill, R.T. Isolation and diversity of actinomycetes in the Chesapeake Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 997–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Fenical, W.; Jensen, P.R. Developing a new resource for drug discovery: Marine actinomycete bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Cao, Y.R.; Zhao, L.X.; Wang, Q.; Jin, R.X.; He, W.X.; Xue, Q.H. Treatment of ultrasonic to soil sample for increase of the kind of rare actinomycetes. Acta Microbiol. Sin. 2010, 50, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Margulis, L.; Chapman, M.J. Kingdoms and domains. In An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science, Marine Biological Laboratory: Woods Hole, MA, USA, 2009; p. 732. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, P.R.; Dwight, R.; Fenical, W. Distribution of actinomycetes in near-shore tropical marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.H.; Azman, A.S.; Zainal, N.; Eng, S.K.; Ab Mutalib, N.S.; Yin, W.F.; Chan, K.G. Microbacterium mangrovi sp. nov., an amylolytic actinobacterium isolated from mangrove forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 3513–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.H.; Azman, A.S.; Zainal, N.; Yin, W.F.; Mutalib, N.S.; Chan, K.G. Sinomonas humi sp. nov., an amylolytic actinobacterium isolated from mangrove forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Li, L.; Wei, B.; Tang, Y.L.; Deng, Z.X.; Sun, M.; Hong, K. Micromonospora wenchangensis sp. nov., isolated from mangrove soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2389–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mincer, T.J.; Jensen, P.R.; Kauffman, C.A.; Fenical, W. Widespread and persistent populations of a major new marine actinomycete taxon in ocean sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5005–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredholdt, H.; Tjaervik, E.; Johnsen, G.; Zotchev, S.B. Actinomycetes from sediments in the Trondheim fjord, Norway: Diversity and biological activity. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokare, C.R.; Mahadik, K.R.; Kadam, S.S. Isolation of bioactive marine Actinomycetes from sediments isolated from Goa and Maharashtra coastlines (west coast of India). Indian J. Mar. Sci. 2004, 33, 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- Naikpatil, S.V.; Rathod, J.L. Selective isolation and antimicrobial activity of rare Actinomycetes from mangrove sediment of Karwar. J. Ecobiotechnol. 2011, 3, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mangamuri, U.K.; Muvva, V.; Poda, S.; Kamma, S. Isolation, identification and molecular characterization of rare Actinomycetes from mangrove ecosystem of Nizampatnam. Malays. J Microbiol. 2012, 8, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terahara, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Imada, C. An effective method based on wet-heat treatment for the selective isolation of Micromonospora from estuarine sediments. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, G.; Rojas-Jiménez, K.; Jaspars, M.; Tamayo-Castillo, G. Study of the diversity of culturable Actinomycetes in the North Pacific and Caribbean coasts of Costa Rica. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2009, 96, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Gao, A.H.; Xie, Q.Y.; Gao, H.; Zhuang, L.; Lin, H.P.; Yu, H.P.; Li, J.; Yao, X.S.; Goodfellow, M.; et al. Actinomycetes for marine drug discovery isolated from mangrove soils and plants in China. Mar. Drugs 2009, 7, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bredholdt, H.; Galatenko, O.A.; Engelhardt, K.; Tjaervik, E.; Terekhova, L.P.; Zotchev, S.B. Rare actinomycete bacteria from the shallow water sediments of the Trondheim fjord, Norway: Isolation, diversity and biological activity. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 2756–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumsille, A.; Undabarrena, A.; González, V.; Claverías, F.; Rojas, C.; Cámara, B. Biodiversity of actinobacteria from the South Pacific and the assessment of Streptomyces chemical diversity with metabolic profiling. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skropeta, D.; Wei, L. Recent advances in deep-sea natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 999–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, K.; Gupta, R.K. Diversity and isolation of rare actinomycetes: An overview. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 39, 256–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Murcia, A.J.; Collins, M.D. A phylogenetic analysis of the genus Leuconostoc based on reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990, 70, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D.; Rodrigues, U.; Ash, C.; Aguirre, M.; Farrow, J.A.E.; Martinez-Murcia, A.; Phillips, B.A.; Williams, A.M.; Wallbanks, S. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Lactobacillus and related lactic acid bacteria as determined by reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1991, 77, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, R.I.; Lin, C.; Key, R.; Montgomery, L.; Stahl, D.A. Diversity among Fibrobacter isolates: Towards a phylogenetic classification. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1992, 15, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G.E.; Wisotzkey, J.D.; Jurtshuk, P., Jr. How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992, 42, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Murcia, A.J.; Benlloch, S.; Collins, M.D. Phylogenetic interrelationships of members of the genera Aeromonas and Pleisiomonas as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing: Lack of congruence with results of DNA-DNA hybridizations. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992, 42, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaberg, R.; Simmon, K.E.; Fisher, M.A. A systematic approach for discovering novel, clinically relevant bacteria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, P.; Parfrey, L.W.; Yarza, P.; Gerken, J.; Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Ludwig, W.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelgrove, P.; Blackburn, T.; Hutchings, P.A.; Alongi, D.M.; Grassle, J.F.; Hummel, H.; King, G.; Koike, I.; Lambshead, P.J.D.; Ramsing, N.B.; et al. The importance of marine sediment biodiversity in ecosystem processes. Ambio 1997, 26, 578–583. [Google Scholar]

- Harino, H.; Arai, T.; Ohji, M.; Miyazaki, N. Organotin contamination in deep sea environment. In Ecotoxicology of Antifouling Biocides; Arai, T., Harino, H., Ohji, M., Langston, W.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Skropeta, D. Deep-sea natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 1131–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden, J.M.; Bett, B.J.; Jones, D.O.B.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Ruhl, H.A. Abyssal hills hidden source of increased habitat heterogeneity, benthic megafaunal biomass and diversity in the deep sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015, 137, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefner, B. Drugs from the deep: Marine natural products as drug candidates. Drug Discov. Today 2003, 8, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, J.E.; Daley, R.J.; Jasper, S. Use of nuclepore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, K.G.; Feig, Y.S. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1980, 25, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Wiebe, W.J. Prokaryotes: The unseen majority. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6578–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Mangwani, N. Ocean acidification and marine microorganisms: Responses and consequences. Oceanologia 2015, 57, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Stewart, A.; Song, B.; Hill, R.T.; Wright, J.L. Biodiversity of actinomycetes associated with caribbean sponges and their potential for natural product discovery. Mar. Biotechnol. 2013, 15, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veyisoglu, A.; Sazak, A.; Cetin, D.; Guven, K.; Sahin, N. Saccharomonospora amisosensis sp. nov., isolated from deep marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3782–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.F.; Chen, W.; He, J.; Zhang, X.M.; Xiong, Z.J.; Sahu, M.K.; Sivakumar, K.; Li, W.J. Saccharomonospora oceani sp. nov. isolated from marine sediments in Little Andaman, India. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.M.; Yang, L.L.; Tian, X.P.; Long, L.J.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.J. Actinophytocola sediminis sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from a marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2834–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Jiang, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, B.B.; Zhang, X.M.; Tian, X.P.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.J. Pseudonocardia sediminis sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lai, H. Amycolatopsis flava sp. nov., a halophilic actinomycete isolated from dead sea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wei, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xue, Q.; Lai, H.; Jiang, C. Saccharopolyspora griseoalba sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from the dead sea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y. Amycolatopsis albispora sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 3860–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y. Pseudonocardia profundimaris sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1693–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Qiao, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.H. Nocardioides pacificus sp. nov., isolated from deep sub-seafloor sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2217–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.F.; Zhong, J.M.; Zhang, X.M.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, E.M.; Tian, X.P.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.J. Nocardioides nanhaiensis sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from a marine sediment sample. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2718–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, L.; Jiang, F.; Qu, Z.; Peng, F. Nocardioides antarcticus sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2615–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Lee, A.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.J.; Khim, J.S.; Yim, U.H.; Kim, B.S. Nocardioides litoris sp. nov., isolated from the Taean seashore. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2332–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Pan, H.Q.; He, J.; Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, Y.G.; Klenk, H.P.; Hu, J.C.; Li, W.J. Description of Streptomonospora sediminis sp. nov. and Streptomonospora nanhaiensis sp. nov., and reclassification of Nocardiopsis arabia Hozzein & Goodfellow 2008 as Streptomonospora arabica comb. nov. and emended description of the genus Streptomonospora. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4447–4455. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.Q.; Zhang, D.F.; Li, L.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Wang, H.F.; Hu, J.C.; Li, W.J. Nocardiopsis oceani sp. nov. and Nocardiopsis nanhaiensis sp. nov., actinomycetes isolated from marine sediment of the South China Sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 3384–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, G. Microbacterium hydrothermale sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from hydrothermal sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 3508–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, M.; Shibata, C.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, K. Agromyces marinus sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from sea sediment. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawlankar, R.R.; Mual, P.; Sonalkar, V.V.; Thorat, M.N.; Verma, A.; Srinivasan, K.; Dastager, S.G. Microbacterium enclense sp. nov., isolated from sediment sample. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2064–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Guan, Y.; Li, J. Microbacterium nanhaiense sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 3697–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, M.; Shibata, C.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, K. Zhihengliuella flava sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from sea sediment, and emended description of the genus Zhihengliuella. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4760–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastager, S.G.; Tang, S.K.; Srinivasan, K.; Lee, J.C.; Li, W.J. Kocuria indica sp. nov., isolated from a sediment sample. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, X.; Wang, S. Nesterenkonia alkaliphila sp. nov., an alkaliphilic, halotolerant actinobacteria isolated from the western Pacific Ocean. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, W.H.; Yuan, C.G.; Chen, J.Y.; Cao, L.X.; Park, D.J.; Xiao, M.; Kim, C.J.; Li, W.J. Kocuria subflava sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment from the Indian Ocean. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.H. Luteococcus sediminum sp. nov., isolated from deep subseafloor sediment of the South Pacific Gyre. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2522–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Sánchez, F.; Sánchez-Román, M.; Amils, R.; Parro, V. Tessaracoccus lapidicaptus sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from the deep subsurface of the Iberian pyrite belt. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 3546–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongphrom, C.; Kim, J.H.; Bora, N.; Kim, W. Tessaracoccus arenae sp. nov., isolated from sea sand. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2008–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastager, S.G.; Mawlankar, R.; Tang, S.K.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Ramana, V.V.; Joseph, N.; Shouche, Y.S. Rhodococcus enclensis sp. nov., a novel member of the genus Rhodococcus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2693–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S.; Ding, P.; Xing, K.; Yuan, B.; Cao, C.L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Jiang, J.H. Nocardia jiangsuensis sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from coastal soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4633–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongsopitanun, W.; Kudo, T.; Mori, M.; Shiomi, K.; Pittayakhajonwut, P.; Suwanborirux, K.; Tanasupawat, S. Micromonospora fluostatini sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 4417–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veyisoglu, A.; Carro, L.; Guven, K.; Cetin, D.; Spröer, C.; Schumann, P.; Klenk, H.P.; Goodfellow, M.; Sahin, N. Micromonospora yasonensis sp. nov., isolated from a black sea sediment. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veyisoglu, A.; Carro, L.; Cetin, D.; Guven, K.; Spröer, C.; Pötter, G.; Klenk, H.P.; Sahin, N.; Goodfellow, M. Micromonospora profundi sp. nov., isolated from deep marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4735–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jung, Y.T.; Won, S.M.; Lee, J.S.; Yoon, J.H. Demequina activiva sp. nov., isolated from a tidal flat. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2042–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Jung, Y.T.; Won, S.M.; Yoon, J.H. Demequina litorisediminis sp. nov., isolated from a tidal flat, and emended description of the genus Demequina. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4197–4203. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, M.; Shibata, C.; Tamura, T.; Yamamura, H.; Hayakawa, M.; Suzuki, K. Janibacter cremeus sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3687–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Ren, H.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Janibacter indicus sp. nov., isolated from hydrothermal sediment of the Indian Ocean. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2353–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.Q.; Li, J.; Qin, S.; Tian, X.P.; Wang, F.Z.; Zhang, S. Georgenia sediminis sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic actinobacterium isolated from sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4243–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Jiao, K.; Zhang, G. Georgenia subflava sp. nov., isolated from a deep-sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 4146–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Kasai, H.; Matsuo, Y.; Shizuri, Y.; Ichikawa, N.; Fujita, N.; Omura, S.; Takahashi, Y. Ilumatobacter nonamiense sp. nov. and Ilumatobacter coccineum sp. nov., isolated from seashore sand. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3404–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Ruan, J.; Han, X.; Huang, Y. Brevibacterium sediminis sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea sediments from the Carlsberg and southwest Indian ridges. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5268–5274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.J.; Miao, T.T.; Lin, X.Z.; Liu, Q.Q.; Chen, G.J. Flaviflexus huanghaiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an actinobacterium of the family Actinomycetaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1863–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, M.; Tamura, T.; Shibata, C.; Yamamura, H.; Hayakawa, M.; Schumann, P.; Suzuki, K. Paraoerskovia sediminicola sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from sea sediment, and emended description of the genus Paraoerskovia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2637–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Jang, G.I.; Cho, B.C. Nocardioides marinquilinus sp. nov., isolated from coastal seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 2594–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Jang, G.I.; Hwang, C.Y.; Kim, E.H.; Cho, B.C. Nocardioides salsibiostraticola sp. nov., isolated from biofilm formed in coastal seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3800–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, G. Nocardioides rotundus sp. nov., isolated from deep seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1932–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, L.; Qiu, D.; Song, L.; Dai, X.; Ruan, J.; Huang, Y. Cellulomonas marina sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3014–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xi, L.; Ruan, J.; Huang, Y. Kocuria oceani sp. nov., isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal plume. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, N.; Mual, P.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.M.; Mayilraj, S. Brachybacterium aquaticum sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from seawater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4705–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gao, J.; Cheung, A.; Liu, B.; Schwendenmann, L. Vegetation and sediment characteristics in expanding mangrove forest in New Zealand. Eastuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 2013, 134, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K. Actinomycetes from mangrove and their secondary metabolites. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 2013, 53, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Supong, K.; Suriyachadkun, C.; Suwanborirux, K.; Pittayakhajonwut, P.; Thawai, C. Verrucosispora andamanensis sp. nov., isolated from a marine sponge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 3970–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supong, K.; Suriyachadkun, C.; Pittayakhajonwut, P.; Suwanborirux, K.; Thawai, C. Micromonospora spongicola sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from a marine sponge in the Gulf of Thailand. J. Antibiot. 2013, 66, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.F.; Li, J.; You, Z.Q.; Zhang, S. Prauserella coralliicola sp. nov., isolated from the coral Galaxea fascicularis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 3341–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Mual, P.; Kumar, N.; Verma, A.; Kumar, A.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Mayilraj, S. Microbacterium aureliae sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from Aurelia aurita, the moon jellyfish. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4665–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukano, H.; Wada, S.; Kurata, O.; Katayama, K.; Fujiwara, N.; Hoshino, Y. Mycobacterium stephanolepidis sp. nov., a rapidly growing species related to Mycobacterium chelonae, isolated from marine teleost fish, Stephanolepis cirrhifer. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2811–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Hyun, D.W.; Soo Kim, P.; Sik Kim, H.; Shin, N.R.; Yun, J.H.; Jung, M.J.; Kim, M.S.; Woong Whon, T.; Bae, J.W. Arthrobacter echini sp. nov., isolated from the gut of a purple sea urchin, Heliocidaris crassispina. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1887–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thawai, C.; Rungjindamai, N.; Klanbut, K.; Tanasupawat, S. Nocardia xestospongiae sp. nov., isolated from a marine sponge in the Andaman sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Kämpfer, P.; Glaeser, S.P.; Busse, H.J.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Hentschel, U. Rubrobacter aplysinae sp. nov., isolated from the marine sponge Aplysina aerophoba. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, P.; Glaeser, S.P.; Busse, H.J.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Ahmed, S.; Hentschel, U. Actinokineospora spheciospongiae sp. nov., isolated from the marine sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Vizcaíno, A.; González, V.; Braña, A.F.; Molina, A.; Acuña, J.L.; García, L.A.; Blanco, G. Myceligenerans cantabricum sp. nov., a barotolerant actinobacterium isolated from a deep cold-water coral. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, M.; Shibata, C.; Saitou, S.; Tamura, T.; Komaki, H.; Ichikawa, N.; Oguchi, A.; Hosoyama, A.; Fujita, N.; Yamamura, H.; et al. Proposal of nine novel species of the genus Lysinimicrobium and emended description of the genus Lysinimicrobium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 4394–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Deng, Z.; Hong, K. Micromonospora zhanjiangensis sp. nov., isolated from mangrove forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 4880–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Hong, K. Micromonospora ovatispora sp. nov. isolated from mangrove soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.Y.; Ren, J.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Deng, Z.X.; Hong, K. Micromonospora mangrovi sp. nov., isolated from mangrove soil. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muangham, S.; Suksaard, P.; Mingma, R.; Matsumoto, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Duangmal, K. Nocardiopsis sediminis sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 3835–3840. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, M.; Shibata, C.; Tamura, T.; Nurkanto, A.; Ratnakomala, S.; Lisdiyanti, P.; Suzuki, K.I. Kocuria pelophila sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from the rhizosphere of a mangrove. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 3276–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.H.; Zainal, N.; Azman, A.S.; Mutalib, N.S.; Hong, K.; Chan, K.G. Mumia flava gen. nov., sp. nov., an actinobacterium of the family Nocardioidaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xing, S.S.; Yuan, W.D.; Wei, H.; Sun, Q.G.; Lin, X.Z.; Huang, H.Q.; Bao, S.X. Pseudonocardia nematodicida sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment in Hainan, China. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015, 108, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.L.; Lin, H.P.; Xie, Q.Y.; Li, L.; Peng, F.; Deng, Z.; Hong, K. Actinoallomurus acanthiterrae sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from rhizosphere soil of the mangrove plant Acanthus ilicifolius. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1874–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksaard, P.; Duangmal, K.; Srivibool, R.; Xie, Q.; Hong, K.; Pathom-aree, W. Jiangella mangrovi sp. nov., isolated from mangrove soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2569–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, M.; Shibata, C.; Nurkanto, A.; Ratnakomala, S.; Lisdiyanti, P.; Tamura, T.; Suzuki, K. Serinibacter tropicus sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from the rhizosphere of a mangrove, and emended description of the genus Serinibacter. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksaard, P.; Mingma, R.; Srisuk, N.; Matsumoto, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Duangmal, K. Nonomuraea purpurea sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from mangrove sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4987–4992. [Google Scholar]

- Duangmal, K.; Muangham, S.; Mingma, R.; Yimyai, T.; Srisuk, N.; Kitpreechavanich, V.; Matsumoto, A.; Takahashi, Y. Kineococcus mangrovi sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genilloud, O. Actinomycetes: Still a source of novel antibiotics. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 1203–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waksman, S.A.; Woodruff, H.B. Bacteriostatic and bactericidal substances produced by a soil actinomyces. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1940, 45, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, S.A.; Woodruff, H.B. Selective antibiotic action of various substances of microbial origin. J. Bacteriol. 1942, 44, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schatz, A.; Waksman, S.A. Effect of streptomycin and other antibiotic substances upon Mycobacterium tuberculosis and related organisms. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1944, 57, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Aalbersberg, W. Marine actinomycetes: An ongoing source of novel bioactive metabolites. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 167, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.S.; Blaskovich, M.A.; Cooper, M.A. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline at the end of 2015. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Feling, R.H.; Buchanan, G.O.; Mincer, T.J.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W. Salinosporamide A: A highly cytotoxic proteasome inhibitor from a novel microbial source, a marine bacterium of the new genus Salinospora. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003, 42, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asolkar, R.N.; Freel, K.C.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W.; Kondratyuk, T.P.; Park, E.J.; Pezzuto, J.M. Arenamides A-C, cytotoxic NFκB Inhibitors from the marine actinomycete Salinispora arenicola. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, K.H.; Nam, S.J.; Locke, J.B.; Kauffman, C.A.; Beatty, D.S.; Paul, L.A.; Fenical, W. Anthracimycin, a potent anthrax antibiotic from a marine-derived actinomycete. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 7822–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutou, A.S.; Yang, I.; Kang, H.; Seo, E.K.; Nam, S.J.; Fenical, W. Nocarimidazoles A and B from a marine-derived actinomycete of the genus Nocardiopsis. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2846–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, R.; Piggott, A.M.; Quezada, M.; Capon, R.J. Nocardiopsins C and D and nocardiopyrone A: New polyketides from an Australian marine-derived Nocardiopsis sp. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Fukuda, T.; Terahara, T.; Harunari, E.; Imada, C.; Tomoda, H. Diketopiperazines, inhibitors of sterol O-acyltransferase, produced by a marine-derived Nocardiopsis sp. KM2-16. J. Antibiot. 2015, 68, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skellam, E.J.; Stewart, A.K.; Strangman, W.K.; Wright, J.L. Identification of micromonolactam, a new polyene macrocyclic lactam from two marine Micromonospora strains using chemical and molecular methods: clarification of the biosynthetic pathway from a glutamate starter unit. J. Antibiot. 2013, 66, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento-Vizcaíno, A.; Braña, A.F.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; Martín, J.; de Pedro, N.; Cruz, M.; Díaz, C.; Vicente, F.; Acuña, J.L.; Reyes, F.; et al. Paulomycin G, a new natural product with cytotoxic activity against tumor cell lines produced by deep-sea sediment derived Micromonospora matsumotoense M-412 from the Avilés Canyon in the Cantabrian sea. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeremeh, K.; Acquah, K.S.; Sazak, A.; Houssen, W.; Tabudravu, J.; Deng, H.; Jaspars, M. Butremycin, the 3-hydroxyl derivative of ikarugamycin and a protonated aromatic tautomer of 5′-methylthioinosine from a Ghanaian Micromonospora sp. K310. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Adnani, N.; Braun, D.R.; Ellis, G.A.; Barns, K.J.; Parker-Nance, S.; Guzei, I.A.; Bugni, T.S. Micromonohalimanes A and B: Antibacterial halimane-type diterpenoids from a marine Micromonospora species. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2968–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullowney, M.W.; ÓhAinmhire, E.; Tanouye, U.; Burdette, J.E.; Pham, V.C.; Murphy, B.T. A pimarane diterpene and cytotoxic angucyclines from a marine-derived Micromonospora sp. in Vietnam’s east sea. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5815–5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; MacMillan, J.B. Thiasporines A-C, thiazine and thiazole derivatives from a marine-derived Actinomycetospora chlora. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Anjum, K.; Song, T.; Wang, W.; Yu, S.; Huang, H.; Lian, X.Y.; Zhang, Z. A new curvularin glycoside and its cytotoxic and antibacterial analogues from marine actinomycete Pseudonocardia sp. HS7. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyeremeh, K.; Acquah, K.S.; Camas, M.; Tabudravu, J.; Houssen, W.; Deng, H.; Jaspars, M. Butrepyrazinone, a new pyrazinone with an unusual methylation pattern from a Ghanaian Verrucosispora sp. K51G. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 5197–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Zhou, T.T.; Xie, C.L.; Zhang, G.Y.; Yang, X.W. Microindolinone A, a novel 4,5,6,7-tetrahydroindole, from the deep-sea-derived actinomycete Microbacterium sp. MCCC 1A11207. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Song, Y.; Gao, J.; Jung, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory dimeric indole derivatives from the marine actinomycetes Rubrobacter radiotolerans. Fitoterapia 2015, 102, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, Y.; Bae, M.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Oh, K.B.; Shin, J.; Oh, D.C. A new benzofuran glycoside and indole alkaloids from a sponge-associated rare actinomycete, Amycolatopsis sp. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 2326–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyche, T.P.; Standiford, M.; Hou, Y.; Braun, D.; Johnson, D.A.; Johnson, J.A.; Bugni, T.S. Activation of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 pathway by novel natural products halomadurones A-D and a synthetic analogue. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 5089–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Kong, F.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W. Cyanogramide with a new spiro[indolinone-pyrroloimidazole] skeleton from Actinoalloteichus cyanogriseus. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 3708–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, H.; Chen, L.; Uribe, P.; Bull, A.T.; Goodfellow, M.; Jiang, H.; Lian, Y. A new 20-membered macrolide produced by a marine-derived Micromonospora strain. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013, 27, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.C.; Kwon, O.W.; Park, J.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, H.C. Nocapyrones H-J, 3,6-disubstituted α-pyrones from the marine actinomycete Nocardiopsis sp. KMF-001. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.C.; Li, S.; Nam, S.J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Nocardiamides A and B, two cyclohexapeptides from the marine-derived actinomycete Nocardiopsis sp. CNX037. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, L.; Nam, S.-J.; Fukuda, T.; Yamanaka, K.; Kauffman, C.A.; Jensen, P.R.; Fenical, W.; Moore, B.S. Structures and comparative characterization of biosynthetic gene clusters for cyanosporasides, enediyne-derived natural products from marine actinomycetes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4171–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Cheng, C.; Viegelmann, C.; Zhang, T.; Grkovic, T.; Ahmed, S.; Quinn, R.J.; Hentschel, U.; Edrada-Ebel, R. Dereplication strategies for targeted isolation of new antitrypanosomal actinosporins A and B from a marine sponge associated-Actinokineospora sp. EG49. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1220–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.A.; Wyche, T.P.; Fry, C.G.; Braun, D.R.; Bugni, T.S. Solwaric acids A and B, antibacterial aromatic acids from a marine Solwaraspora sp. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzoss, L.; Fukuda, T.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Jimenez, P.; La Clair, J.J.; Fenical, W. Seriniquinone, a selective anticancer agent, induces cell death by autophagocytosis, targeting the cancer-protective protein dermcidin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14687–14692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Mei, X.; Wang, Y.; Jia, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, W. Acyclic congeners from Actinoalloteichus cyanogriseus provide insights into cyclic bipyridine glycoside formation. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4264–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyche, T.P.; Piotrowski, J.S.; Hu, Y.; Braun, D.; Deshpande, R.; Mcllwain, S.; Ong, I.M.; Myers, C.L.; Guzei, I.A.; Westler, W.M.; et al. Forazoline A: Marine-derived polyketide with antifungal in vivo efficacy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 11583–11586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Abdel-Mageed, W.M.; Ebel, R.; Bull, A.T.; Goodfellow, M.; Fiedler, H.P.; Jaspars, M. Dermacozines H-J isolated from a deep-sea strain of Dermacoccus abyssi from Mariana Trench sediments. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltamany, E.E.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Ibrahim, A.K.; Hassanean, H.A.; Hentschel, U.; Ahmed, S.A. New antibacterial xanthone from the marine sponge-derived Micrococcus sp. EG45. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 4939–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Ogura, H.; Akasaka, K.; Oikawa, T.; Matsuura, N.; Imada, C.; Yasuda, H.; Igarashi, Y. Nocapyrones: α- and γ-pyrones from a marine-derived Nocardiopsis sp. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 4110–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, T.; Itoh, M.; Izumikawa, M.; Kozone, I.; Sakata, N.; Tsuchida, T.; Shin-ya, K. New hydroxamate metabolite, MBJ-0003, from Micromonospora sp. 29867. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Lin, H.; Proksch, P.; Tang, X.; Shao, Z.; Lin, W. Microbacterins A and B, new peptaibols from the deep sea actinomycete Microbacterium sediminis sp. nov. YLB-01(T). Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, C.J.; Navarro, G.; Ebert, D.; DeRisi, J.; Linington, R.G. Salinipostins A-K, long-chain bicyclic phosphotriesters as a potent and selective antimalarial chemotype. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, M.; Liu, B.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; He, H.; Ping, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C. Saccharothrixones A-D, tetracenomycin-type polyketides from the marine-derived actinomycete Saccharothrix sp. 10-10. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2260–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, Q.V.; Tran, V.H.; Maia, H.D.; Le, C.V.; Hong MLe, T.; Murphy, B.T.; Chau, V.M.; Pham, V.C. Antimicrobial metabolites from a marine-derived actinomycete in Vietnam’s east sea. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.M.; Zhang, D.F.; Li, W.J.; Lu, C.H. Pseudonocardides A-G, new γ-butyrolactones from marine-derived Pseudonocardia sp. YIM M13669. Helv. Chim. Acta 2016, 99, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Saurav, K.; Yu, Z.; Mándi, A.; Kurtán, T.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, C. α-Pyrones with diverse hydroxy substitutions from three marine-derived Nocardiopsis strains. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, Q.V.; Tran, V.H.; Mai, H.D.; Le, C.V.; Hong, M.L.T.; Murphy, B.T.; Chau, V.M.; Pham, V.C. Secondary metabolites from an actinomycete from Vietnam’s east sea. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.L.; Niu, S.W.; Zhou, T.T.; Zhang, G.Y.; Yang, Q.; Yang, X.W. Chemical constituents and chemotaxonomic study on the marine actinomycete Williamsia sp. MCCC 1A11233. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2016, 67, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Han, C.; Gu Lee, T.; Chin, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, W.; Jeong Paik, M.; Hwan Won, D.; Jeong, G.; Ko, J.; et al. Marinopyrones A-D, α-pyrones from marine-derived actinomycetes of the family Nocardiopsaceae. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1997–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xie, F.; Ren, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Abdel-Mageed, W.M.; Liu, M.; Han, J.; Oyeleye, A.; et al. Anti-MRSA and anti-TB metabolites from marine-derived Verrucosispora sp. MS100047. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 7437–7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Takahashi, M.; Nagai, K.; Harunari, E.; Imada, C.; Tomoda, H. Isomethoxyneihumicin, a new cytotoxic agent produced by marine Nocardiopsis alba KM6-1. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.L.; Liu, Q.; Xia, J.M.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Shao, Z.Z.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.W. Anti-allergic compounds from the deep-sea-derived actinomycete Nesterenkonia flava MCCC 1K00610. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Sun, M.W.; Shi, H.; Lu, C.H. α-pyrone derivatives from a marine actinomycete Nocardiopsis sp. YIM M13066. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 2245–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.Y.; Le, T.C.; Lee, T.G.; Yang, I.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.; Kang, K.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Lim, K.M.; Yee, S.T.; et al. Saccharomonopyrones A-C, New α-pyrones from a marine sediment-derived bacterium Saccharomonospora sp. CNQ-490. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, T.; Zhen, X.; Li, X.L.; Chen, J.J.; Chen, T.J.; Yang, J.L.; Zhu, P. Tetrocarcin Q, a new spirotetronate with a unique glycosyl group from a marine-derived actinomycete Micromonospora carbonacea LS276. Mar. Drugs 2017, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, X.; Ding, W.; Huang, H.; Gu, Y.C.; Duan, Y.; Ju, J. Antimicrobial spirotetronate metabolites from marine-derived Micromonospora harpali SCSIO GJ089. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, X.; Li, W.; Lu, C.; Shen, Y. New diketopiperazine derivatives with cytotoxicity from Nocardiopsis sp. YIM M13066. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 795–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Sawa, R.; Yamasaki, M.; Hayashi, C.; Umekita, M.; Hatano, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Mizumoto, K.; Nomoto, A. Kribellosides, novel RNA 5′-triphosphatase inhibitors from the rare actinomycete Kribbella sp. MI481-42F6. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braña, A.F.; Sarmiento-Vizcaíno, A.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; Otero, L.; Fernández, J.; Palacios, J.J.; Martín, J.; de la Cruz, M.; Díaz, C.; Vicente, F.; et al. Branimycins B and C, antibiotics produced by the abyssal actinobacterium Pseudonocardia carboxydivorans M-227. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Ou, J.; Li, W.; Lu, C. Quinoline and naphthalene derivatives from Saccharopolyspora sp. YIM M13568. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemert, N.; Alanjaryab, M.; Weber, T. The evolution of genome mining in microbes-a review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hug, J.J.; Bader, C.D.; Remškar, M.; Cirnski, K.; Müller, R. Concepts and methods to aaccess novel antibiotics from actinomycetes. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, X. Diversity of gene clusters for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis revealed by metagenomic analysis of the yellow sea sediment. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.; Baltz, R.H. Natural product discovery: Past, present, and future. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 43, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, M.A.; Alanjary, M.M.; Aguinaldo, K.; Korobeynikov, A.; Podell, S.; Patin, N.; Lincecum, T.; Jensen, P.R.; Ziemert, N.; Moore, B.S. Sequencing rare marine actinomycete genomes reveals high density of unique natural product biosynthetic gene clusters. Microbiology 2016, 162, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, C.; Medema, M.H.; van der Oost, J.; Sipkema, D. Exploration and exploitation of the environment for novel specialized metabolites. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 50, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K.; Reynolds, K.A.; Kersten, R.D.; Ryan, K.S.; Gonzalez, D.J.; Nizet, V.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Moore, B.S. Direct cloning and refactoring of a silent lipopeptide biosynthetic gene cluster yields the antibiotic taromycin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, K.R.; Crüsemann, M.; Lechner, A.; Sarkar, A.; Li, J.; Ziemert, N.; Wang, M.; Bandeira, N.; Moore, B.S.; Dorrestein, P.C.; et al. Molecular networking and pattern-based genome mining improves discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters and their products from Salinispora species. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, T.K.; Hughes, C.C.; Moore, B.S. Sioxanthin, a novel glycosylated carotenoid, reveals an unusual subclustered biosynthetic pathway. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 2158–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, C.J.; Donia, M.S.; Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; Ray, D.; Raskatov, J.A.; Green, R.E.; McKerrow, J.H.; Fischbach, M.A.; Linington, R.G. Genome-directed lead discovery: Biosynthesis, structure elucidation, and biological evaluation of two families of polyene macrolactams against Trypanosoma brucei. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2373–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Chen, H.; Guo, Z.; Liu, N.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Xiang, W.; Chen, Y. Discovery of pentangular polyphenols hexaricins A-C from marine Streptosporangium sp. CGMCC 4.7309 by genome mining. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 4189–4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Gan, M. Tetrocarcins N and O, glycosidic spirotetronates from a marine-derived Micromonospora sp. identified by PCR-based screening. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 91773–91778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Carrasco, Y.P.; MacMillan, J.B.; De Brabander, J.K. Rifamycin biosynthetic congeners: Isolation and total synthesis of rifsaliniketal and total synthesis of salinisporamycin and saliniketals A and B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7130–7142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Nie, F.; Wu, Z.; Yang, C.; Zhang, L.; Tian, X.; Zhang, C. Isolation, structure elucidation and biosynthesis of benzo[b]fluorine nenestatin A from deep-sea derived Micromonospora echinospora SCSIO 04089. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 3585–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.; Moitinho-Silva, L.; Lurgi, M.; Björk, J.R.; Easson, C.; Astudillo-García, C.; Olson, J.B.; Erwin, P.M.; López-Legentil, S.; Luter, H.; et al. Diversity, structure and convergent evolution of the global sponge microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunagawa, S.; Coelho, L.P.; Chaffron, S.; Kultima, J.R.; Labadie, K.; Salazar, G.; Djahanschiri, B.; Zeller, G.; Mende, D.R.; Alberti, A.; et al. Ocean plankton. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 2015, 348, 1261359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pre-treatment | Marine Source | Isolation Medium | Incubation Temperature/Time | Target Rare Genera | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat | |||||

| Incubation in water bath at 50 °C for 60 min | WS | Starch-casein agar + 10 µg nalidixic acid, 25 µg nystatin and 10 µg cycloheximide | 24 °C for 28 days | Micromonospora | [45] |

| WS | M1 agar + 75 µg cycloheximide | 20–24 °C for 14–28 days | Micromonospora | [49] | |

| 50 °C for 15 min | WS | Starch-casein agar + 10 µg nystatin and 25 µg cycloheximide | 28 °C for 7 days | Monashia, Microbacterium and Sinomonas | [23,50,51] |

| 55 °C for 20 min | WS | Glucose peptone tryptone agar + 50 mg nystatin, 50 mg cycloheximide, 25 mg novobiocin and 20 mg nalidixic acid | 28 °C for 21 days | Micromonospora | [52] |

| Incubation in water bath at 55 °C for 6 min | DS | M1–M5 agar + 100 µg cycloheximide and 5 µg rifampin | 25–28 °C for 2–6 weeks | Micromonospora and Salinispora | [11,53] |

| Incubation in water bath at 60 °C for 10 min | DS | M1–M12 agar + 100 µg cycloheximide and 50 µg nystatin | 28 °C for 3 months | Micromonospora and Salinispora | [28] |

| Speedvac 30 °C, 16 h; 120 °C, 60 min | DS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (50 μg/mL), nystatin (75 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/mL) | 20 °C for 2–6 weeks | Rare actinomycetes | [54] |

| 41 °C for 10, 30 and 60 days | DS | Different selective media | 28 °C for 2–3 weeks | Streptoverticillium, Catellatospora, Nocardia and Actinopolyspora | [55] |

| 70 °C for 15 min | WS | Different selective media | 25 °C for 4 weeks | Micromonospora, Microbispora, Actinoplanes and Actinomadura | [56] |

| 55 °C for 15 min | DS | Asparagine-glucose agar medium + nalidixic acid (25 μg/mL) and secnidazole (25 μg/mL) | 25 °C for 2 weeks | Pseudonocardia | [57] |

| 45, 55 or 65 °C for 30 min | WS | ISP-3 and ISP-4 + cycloheximide (50 μg/mL), nystatin (50 μg/mL), and nalidixic acid (20 μg/mL) | 27 °C for 3 weeks | Micromonospora | [58] |

| 60 °C for 6 min | WS | M1 medium and Glucose-yeast extract medium + nystatin (50 μg/mL), and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL) | 25 °C for 6 weeks | Nocardia, Nonomuraea, Rhodococcus, Saccharopolyspora and Gordonia | [59] |

| Physical | |||||

| Dry in laminar air flow hood; Stamping | WS/DS | M1–M12 agar + 100 µg cycloheximide and 50 µg nystatin | 28 °C for 3 months | Micromonospora and Salinispora | [28,53] |

| Mechanic | |||||

| Shake with glass beads for 30 s and settled for 5 min | WS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (50 μg/mL), nystatin (75 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/mL) | 20 °C for 6 weeks | Rare actinomycetes | [54] |

| Chemical/+ Heat | |||||

| 1.5% phenol + 30 min at 30 °C | DS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (50 μg/mL), nystatin (75 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/mL) | 20 °C for 2–6 weeks | Micromonospora | [4] |

| 0.02% benzethonium chloride + 30 min at 30 °C | DS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (50 μg/mL), nystatin (75 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/mL) | 20 °C for 2–6 weeks | Rare actinomycetes | [54] |

| 0.05% SDS and 6% yeast extract (40 °C, 200 rpm, 30 min) | DS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (25–100 μg/mL) and nystatin (25–50 μg/mL) | 28 °C for 1–12 weeks | Actinomadura, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Nonomuraea, Rhodococcus and Verrucosispora | [60] |

| 1.5% phenol | DS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (50 μg/mL), nystatin (75 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/mL) | 20 °C for 2–6 weeks | Rare actinomycetes | [54] |

| Chloramine-T | DS | Different selective media + cycloheximide (25–100 μg/mL) and nystatin (25–50 μg/mL) | 28 °C for 1–12 weeks | Actinomadura, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Nonomuraea, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces and Verrucosispora | [60] |

| Centrifugation | |||||

| Differential centrifugation | WS | Selective media | 28 °C for 12 weeks | Micromonospora, Rhodococcus and Streptomyces | [30] |

| Freezing | |||||

| Freeze (−20 °C, 24 h), thawed, dilution | WS | M1-M12 agar + 100 µg cycloheximide and 50 µg nystatin | 28 °C for 3 months | Micromonospora and Salinispora | [28] |

| Freeze at −18 °C | WS | Different selective media + nystatin (50 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL) | 28 °C for 2–3 weeks | Nocardiopsis, Nocardia and Streptosporangium | [61] |

| Radiation | |||||

| UV irradiation for 30 s (distance 20 cm, 254 nm, 15 W) | WS | Different selective media + nystatin (50 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL) | 28 °C for 2–3 weeks | Nocardiopsis, Nocardia and Pseudonocardia | [61] |

| Superhigh frequency radiation inmicrowave oven for 45 s (2460 MHz, 80 W) | WS | Different selective media + nystatin (50 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL) | 28 °C for 2–3 weeks | Streptosporangium and Rhodococcus | [61] |

| Extremely high frequency radiation (1 kHz within wavelength band of 8–11.5 mm) | WS | Different selective media + nystatin (50 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL) | 28 °C for 2–3 weeks | Nocardiopsis, Nocardia and Streptosporangium | [61] |

| Strain/Family | Nature of Sample | Isolation Medium | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomonospora amisosensis/Pseudonocardiaceae | Deep marine sediment at a depth of 60 m | SM3 medium (yeast nitrogen base 67.0 g, casamino acids 100 mg were added to a litre of distilled water and the solution sterilised using cellulose filters (0.20 mm) prior to the addition of sterilised di-potassium hydrogen phosphate (200 mL; 10%, w/v); 100 mL of this basal medium was added to 900 mL of sterilised molten agar (1.5%, w/v) followed by filter sterilised solutions of D(+) melezitose (1%, w/v), cycloheximide (50 µg mL−1), neomycin sulphate (4 µg mL−1) and nystatin (50 µg mL−1) | [82] |

| Saccharomonospora oceani/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine sediment | Trypticase soy broth agar (DSMZ Medium 535) | [83] |

| Actinophytocola sediminis/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of 2439 m | Starch casein nitrate agar medium (10.0 g soluble starch, 0.3 g casein, 2 g KNO3, 0.05 g MgSO4.7H2O, 35 g NaCl, 2 g K2HPO4, 0.02 g CaCO3, 10 mg FeSO4, 20 g agar, distilled water 1 L) | [84] |

| Pseudonocardia sediminis/Pseudonocardiaceae | Sea sediment at a depth of 652 m | DSMZ 621 medium (250 mg each of Bacto peptone (Difco), Bacto yeast extract and glucose, as well as 20 mL Hutner’s basal salts medium, 10 mL vitamin solution no. 6, 35 g NaCl and 1000 mL distilled water) | [85] |

| Amycolatopsis flava/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine sediment | CMKA medium [(L−1) 0.5 g casein hydrolysate, 1.5 g mannitol, 1 g KNO3, 2 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g CaCO3, 20 g agar]. The multi-salts comprised of 49% (w/w) MgCl2.6H2O, 32% (w/w) NaCl, 14 % (w/w) CaCl2 and 5 % (w/w) KCl | [86] |

| Saccharopolyspora griseoalba/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine sediment | CMKA medium [(L−1) 0.5 g casein hydrolysate, 1.5 g mannitol, 1 g KNO3, 2 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g CaCO3, 20 g agar]. The multi-salts comprised of 49% (w/w) MgCl2.6H2O, 32% (w/w) NaCl, 14 % (w/w) CaCl2 and 5 % (w/w) KCl | [87] |

| Amycolatopsis albispora/Pseudonocardiaceae | Deep-sea sediment at a depth of −2945 m | Modified Zobell 2216E agar (1.0 g yeast extract, 5.0 g tryptone, 34 g NaCl, 15 g agar and 1 L distilled water) | [88] |

| Pseudonocardia profundimaris/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of −7118 m | Modified ZoBell 2216E agar plates (0.5% tryptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 3.4% sodium chloride and 1.8% agar) | [89] |

| Nocardioides pacificus/Nocardioidaceae | Deep sub-seafloor sediment at a depth of 107.3–107.4 m | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [90] |

| Nocardioides nanhaiensis/Nocardioidaceae | Sea sediment at a depth of 880 m | DSMZ 621 medium (250 mg each of Bacto peptone (Difco), Bacto yeast extract and glucose, as well as 20 mL Hutner’s basal salts medium, 10 mL vitamin solution no. 6, 35 g NaCl and 1000 mL distilled water) | [91] |

| Nocardioides antarcticus/Nocardioidaceae | Marine sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Becton Dickinson) | [92] |

| Nocardioides litoris/Nocardioidaceae | Marine beach sediment | Starch casein agar (1% soluble starch, 0.03% casein, 0.2% KNO3, 0.2% NaCl, 0.005% MgSO4.7H2O, 0.2% K2HPO4, 0.02% CaCO3, 0.001% FeSO4.7H2O, 1.8% agar) | [93] |

| Nocardioides flavus/Nocardioidaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of −7068 m | Seawater agar (15.0 g agar and 1 L natural seawater) | [35] |

| Streptomonospora sediminis/Nocardiopsaceae | Marine sediment | Agar medium (glycerine 10.0 g, l-arginine 5.0 g, (NH4)2SO4 2.64 g; KH2PO4 2.38 g, K2HPO4 5.65 g, MgSO4.7H2O 1.0 g, CuSO4.5H2O 0.0064 g, FeSO4.7H2O 0.0011 g; MnCl2.4H2O 0.0079 g; ZnSO4.7H2O 0.0015 g, agar 15.0 g; distilled water 1.0 L) | [94] |

| Streptomonospora nanhaiensis/Nocardiopsaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of 2918 m | Agar medium (glycerine 10.0 g, l-arginine 5.0 g, (NH4)2SO4 2.64 g; KH2PO4 2.38 g, K2HPO4 5.65 g, MgSO4.7H2O 1.0 g, CuSO4.5H2O 0.0064 g, FeSO4.7H2O 0.0011 g; MnCl2.4H2O 0.0079 g; ZnSO4.7H2O 0.0015 g, agar 15.0 g; distilled water 1.0 L) | [94] |

| Nocardiopsis oceani/Nocardiopsaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of 2460 m | Gauze’s synthetic medium no. 1 (soluble starch 20.0 g, KNO3 1.0 g, NaCl 0.5 g, MgSO4.7H2O, 0.5 g, K2HPO4 0.5 g, FeSO4.7H2O 10.0 mg, agar 15.0 g and distilled water 1.0 L) | [95] |

| Nocardiopsis nanhaiensis/Nocardiopsaceae | |||

| Microbacterium hydrothermale/Microbacteriaceae | Hydrothermal sediment at a depth of 2943 m | Modified ZoBell 2216E agar plates (0.5% tryptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 3.4% sodium chloride and 1.8% agar) | [96] |

| Agromyces marinus/Microbacteriaceae | Sea sediment | NBRC medium 802 [Polypepton (Wako) 2 g, yeast extract 0.4 g, MgSO4.7H2O 0.2 g and agar 15 g in 1.0 L distilled water supplemented with NaCl (30 g−l), cycloheximide (50 mg−l) and nalidixic acid (20 mg−l)]. | [97] |

| Microbacterium enclense/Microbacteriaceae | Marine sediment | Marine agar (HiMedia) | [98] |

| Microbacterium nanhaiense/Microbacteriaceae | Sea sediment at a depth of 2093 m | Yeast extract/malt extract agar (1 L seawater, 0.5 g malt extract, 0.2 g yeast extract, 0.1 g glucose and 20 g agar) | [99] |

| Zhihengliuella flava/Micrococcaceae | Sea sediment | NBRC medium 802 (0.2% polypeptone, 0.04% yeast extract, 0.02% MgSO4.7H2O and 1.5% agar) | [100] |

| Kocuria indica/Micrococcaceae | Marine sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [101] |

| Nesterenkonia alkaliphila/Micrococcaceae | Deep-sea sediment at a depth of 7118 m | Modified ISP 1 (1 L natural seawater, 10 g glucose, 5 g peptone, 5 g yeast extract, 0.2 g MgSO4.7H2O, 10 g NaHCO3, 27 g Na2CO3.10H2O and 15 g agar) | [102] |

| Kocuria subflava/Micrococcaceae | Marine sediment | No. 38 medium [(L−1) yeast extract 0.4 g; glucose 0.4 g; malt extract 0.4 g; B-vitamin trace 1 mL (0.5 mg each of thiamine-HCl (B1), riboflavin, niacin, pyridoxin, ca-pantothenate, inositol, p-aminobenzoic acid, and 0.25 mg of biotin, agar 15 g, distilled water 1000 mL] | [103] |

| Luteococcus sediminum/Propionibacteriaceae | Deep subseafloor sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [104] |

| Mariniluteicoccus flavus (novel genus)/Propionibacteriaceae | Deep-sea sediment at a depth of 2439 m | HP agar medium (5 g fucose, 1 g proline, 1 g (NH4)2SO4, 2 g CaCl2, 1 g K2HPO4, B vitamin mixture (0.5 mg each thiamine hydrochloride, riboflavin, niacin, pyridoxine, calcium pantothenate, inositol and p-aminobenzoic acid and 0.25 mg biotin), 35 g NaCl, 12 g agar, 1000 mL distilled water) | [43] |

| Tessaracoccus lapidicaptus/Propionibacteriaceae | Deep subsurface sediment at a depth of 297 m | Anoxic F4 medium (0.4 g NaCl, 0.4 g NH4Cl, 0.3 g MgCl2.6H2O, 0.05 g CaCl2.2H2O, 1 g yeast extract, 2 g peptone, 1 g glucose, 1 g succinic anhydride, 7.5 g NaHCO3, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g Na2S, 1 mg resazurin and 1 L distilled water) | [105] |

| Tessaracoccus arenae/Propionibacteriaceae | Sea sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [106] |

| Rhodococcus enclensis/Nocardiaceae | Marine sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [107] |

| Nocardia jiangsuensis/Nocardiaceae | Coastal sediment | Starch arginine agar (2.5 g soluble starch, 1.0 g arginine, 1.0 g (NH4)2SO4, 2.0 g CaCl2, 1.0 g K2HPO4, 0.2 g MgSO4.7H2O, 10 mg FeSO4.7H2O, 15.0 g agar supplemented with 3% (w/v) NaCl, nystatin and nalidixic acid) | [108] |

| Micromonospora fluostatini/Micromonosporaceae | Marine sediment | M1 medium (10 g soluble starch, 4 g yeast extract, 2 g peptone, 18 g agar, and 1 L of natural seawater) | [109] |

| Micromonospora yasonensis/Micromonosporaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of 45 m | SM3 medium (Gauze’s medium 2) [20 g casaminoacids, 20 g soluble starch, 4 g yeast extract, 15 g agar, 1 L distilled water] supplemented with filter sterilised cycloheximide (50 µg mL−1), nalidixic acid (10 µg mL−1), novobiocin (10 µg mL−1) and nystatin (50 µg mL−1) | [110] |

| Micromonospora profundi/Micromonosporaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of 45 m | ISP 2 medium (yeast extract 4.0 g, malt extract 10.0 g, dextrose 4.0 g, distilled water 1 L and Bacto agar 20.0 g) | [111] |

| Demequina activiva/Demequinaceae | Tidal flat sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Becton Dickinson) | [112] |

| Demequina litorisediminis/Demequinaceae | Tidal flat sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [113] |

| Janibacter cremeus/Intrasporangiaceae | Sea sediment | NBRC medium 802 (1.0% polypeptone, 0.2% yeast extract, 0.1% MgSO4.7H2O and 1.5% agar) | [114] |

| Janibacter indicus/Intrasporangiaceae | Hydrothermal sediment | ZoBell 2216E agar (0.5% tryptone, 0.1% yeast extract, 3.4%sodium chloride and 1.8% agar) | [115] |

| Georgenia sediminis/Bogoriellaceae | Marine Sediment at a depth of 141 m | Marine agar 2216 (Becton Dickinson) | [116] |

| Georgenia subflava/Bogoriellaceae | Deep sea sediment at a depth of 6310 m water depth | Modified ZoBell 2216E agar (1.0 g yeast extract, 5.0 g tryptone, 1 L of clarified seawater, 15.0 g agar) | [117] |

| Ilumatobacter nonamiense/Acidimicrobiaceae | Seashore sediment | Medium R (NaCl 25 g, MgSO4.7H2O 9 g, CaCl2.2H2O 0.14 g, KCl 0.7 g, Na2.HPO4.12H2O 0.25 g, Na2-EDTA 30 mg, H2BO3 34 mg, FeSO4.7H2O 10 mg, FeCl3.6H2O 1.452 mg, MnCl2.4H2O 4.32 mg, ZnCl2 0.312 mg, CoCl2.6H2O 0.12 mg, NaBr 6.4 mg, Na2MoO.2H2O 0.63 mg, SrCl2.6H2O 3.04 mg, RbCl 0.1415 mg, LiCl 0.61 mg, KI 0.00655 mg, V2O5 0.001785 mg, Cycloheximide 50 mg, Griseofulvin 25 mg, Nalidixic acid 20 mg, Aztreonam 40 mg, RPMI1640 500 mg, Eagle Medium 500 mg, l-Glutamine 15 mg, NaHCO3 100 mg, Agar 20 g and Distilled water 1 L) | [118] |

| Ilumatobacter coccineum/Acidimicrobiaceae | Seashore sand | ||

| Sediminivirga luteola (novel genus)/Brevibacteriaceae | Marine sediment at a depth of −5233 m | Isolation medium (10 g glucose, 5 g peptone, 5 g yeast extract, 0.2 g MgSO4.7H2O, 10 g NaHCO3, 27 g Na2CO3.10H2O, 20 g agar and 1 L natural seawater) | [25] |

| Brevibacterium sediminis/Brevibacteriaceae | Deep-sea sediment at a depth of −2461 m | ISP 2 medium (yeast extract 4.0 g, malt extract 10.0 g, dextrose 4.0 g, distilled water 1 L and Bacto agar 20.0 g) | [119] |

| Halopolyspora alba (novel genus)/Actinopolysporaceae | Sea sediment | CMKA medium [(0.5 g casein acids hydrolysate, 1.5 g mannitol, 1 g KNO3, 2 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g CaCO3, 20 g agar and 20% (w/v) multi-salts]. The multi-salts comprised 49% (w/w) MgCl2, 32% (w/w) NaCl, 14% (w/w) CaCl2 and 5% (w/w) KCl | [24] |

| Haloactinomyces albus (novel genus)/Actinopolysporaceae | Marine sediment | CMKA medium [(0.5 g casein acids hydrolysate, 1.5 g mannitol, 1 g KNO3, 2 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g CaCO3, 20 g agar and 20% (w/v) multi-salts]. The multi-salts comprised 49% (w/w) MgCl2, 32% (w/w) NaCl, 14% (w/w) CaCl2 and 5% (w/w) KCl | [26] |

| Flaviflexus huanghaiensis (novel genus)/Actinomycetaceae | Coastal sediment | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [120] |

| Paraoerskovia sediminicola/Cellulomonadaceae | Sea sediment | NBRC medium 802 (1.0% polypeptone, 0.2% yeast extract, 0.1% MgSO4.7H2O and 1.5% agar) | [121] |

| Strain/Family | Nature of Sample | Isolation Medium | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nocardioides marinquilinus/Nocardioidaceae | Coastal seawater | Marine agar (Difco) | [122] |

| Nocardioides salsibiostraticola/Nocardioidaceae | Seawater at a depth of 1 m | R2A agar (Difco) | [123] |

| Nocardioides rotundus/Nocardioidaceae | Seawater at a depth of −7001 m | Modified ZoBell 2216E agar (1.0 g yeast extract, 5.0 g tryptone, 1 L clarificated seawater and 15.0 g agar) | [124] |

| Cellulomonas marina/Cellulomonadaceae | Deep-seawater at a depth of 2800 m | ISP 2 medium (yeast extract 4.0 g, malt extract 10.0 g, dextrose 4.0 g, distilled water 1 L and Bacto agar 20.0 g) | [125] |

| Kocuria oceani/Micrococcaceae | Deep-sea hydrothermal plume water at a depth of 2800 m | ISP 2 medium (yeast extract 4.0 g, malt extract 10.0 g, dextrose 4.0 g, distilled water 1 L and Bacto agar 20.0 g) and SMPS (0.1 g peptone, 0.5 g mannitol, 3 g sea salt, 1000 mL distilled water, pH 7.5) agar, supplemented with nalidixic acid, cycloheximide and nystatin (each at 25 μg mL−1). | [126] |

| Pontimonas salivibrio (novel genus)/Microbacteriaceae | Seawater | Marine agar (Difco) | [36] |

| Tamlicoccus marinus (novel genus)/Dermacoccaceae | Seawater | SC-SW agar (1% soluble starch, 0.03% casein, 0.2% KNO3, 0.2% NaCl, 0.2% KH2PO4, 0.002% CaCO3, 0.005% MgSO4.7H2O, 0.001% FeSO4.7H2O, 1.8% agar, 60% natural seawater and 40% distilled water) | [37] |

| Brachybacterium aquaticum/Dermabacteraceae | Seawater | Tryptic soy agar medium (HiMedia) | [127] |

| Strain/Family | Nature of Sample | Isolation Medium | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verrucosispora andamanensis/Micromonosporaceae | Marine sponge Xestospongia sp. | Starch-casein nitrate seawater agar (10 g soluble starch, 1 g sodium caseinate, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4 and 18 g agar in 1 L of seawater) | [130] |

| Micromonospora spongicola/Micromonosporaceae | Marine sponge at a depth of 5 m | Starch-casein nitrate agar (10 g soluble starch, 1 g sodium caseinate, 2 g KNO3, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4 and 18 g agar in 1 L seawater) | [131] |

| Prauserella coralliicola/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine coral Galaxea fascicularis at a depth of 5 m | Isolation medium (yeast extract 0.25 g, K2HPO4 0.5 g, agar 12 g, 500 mL seawater and 500 mL distilled water) | [132] |

| Saccharopolyspora spongiae/Pseudonocardiaceae | Marine sponge Scopalina ruetzleri at depths between 20 and 30 m | M1 medium [1% starch, 0.4% yeast extract, 0.2% peptone, 2% agar containing artificial seawater (33 g red sea salt L−1) amended with cycloheximide and nystatin (each at 25 µg mL−1)] | [40] |

| Microbacterium aureliae/Microbacteriaceae | Moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita | Zobell marine agar (HiMedia) and Tryptic soy agar (HiMedia) | [133] |

| Mycobacterium stephanolepidis/Mycobacteriaceae | Marine teleost fish Stephanolepis cirrhifer | Middlebrook 7H11 agar with oleic albumin dextrose catalase (OADC) enrichment (Becton Dickinson) | [134] |

| Marmoricola aquaticus/Nocardioidaceae | marine sponge Glodia corticostylifera | M1 agar (soluble starch 10 g L−1, yeast extract 4 g L−1, peptone 2 g L−1, agar 15 g L−1, 80% artificial seawater) | [38] |

| Arthrobacter echini/Micrococcaceae | Purple sea urchin Heliocidaris crassispina | Marine agar 2216 (Difco) | [135] |

| Ornithinimicrobium algicola/Intrasporangiaceae | Marine green alga Ulva sp. | Modified R2A medium (yeast extract 0.5 g, peptone 0.5 g, casein enzyme hydrolysate 0.5 g, yeast extract 0.5 g, glucose 0.5 g, water soluble starch 0.5 g, dipotassium phosphate 0.3 g, magnesium sulphate 0.05 g, sodium pyruvate 0.3 g, sodium chloride 20.0 g and distilled water 1000 mL) | [41] |

| Nocardia xestospongiae/Nocardiaceae | Marine sponge Xestospongia sp. | Modified starch-casein nitrate seawater agar containing 10 g soluble starch, 1 g sodium caseinate, 0.5 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g MgSO4 and 18 g agar in 1 L seawater, pH 8.3, supplemented with 50 mg nalidixic acid L−1 and 200 mg nystatin L−1 | [136] |

| Rubrobacter aplysinae/Rubrobacteraceae | Marine sponge Aplysina aerophoba | Tryptone soy agar (Oxoid) | [137] |

| Actinokineospora spheciospongiae/Actinosynnemataceae | Marine sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda | ISP 2 medium (yeast extract 4.0 g, malt extract 10.0 g, dextrose 4.0 g, distilled water 1 L and Bacto agar 20.0 g) | [138] |

| Williamsia spongiae/Gordoniaceae | Marine sponge Amphimedon viridis at depths of between 5 and 10 m | Tryptic Soy Agar [Oxoid; prepared with 80% (v/v) artificial seawater] | [39] |

| Myceligenerans cantabricum/Promicromonosporaceae | Marine coral at a depth of 1500 m | 1/3 Tryptic soy agar (Merck) and and 1/6 M-BLEB agar (9 g MOPS BLEB base (Oxoid) in 1 L Cantabrian seawater, containing the antifungal cycloheximide (80 µg mL−1) and anti-Gram-negative bacteria nalidixic acid (20 mg mL−1) | [139] |

| Strain/Family | Nature of Sample | Isolation Medium | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysinimicrobiumaestuarii/Demequinaceae | Sediment of mangrove tidal flat | 1/5 NBRC medium 802 [0.2% (w/v) polypeptone, 0.04% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.02% (w/v) MgSO4.7H2O and 1.5% (w/v) agar; pH 7.0] supplemented with 5.0% (w/v) NaCl, 0.005% (w/v) cycloheximide and 0.002% (w/v) nalidixic acid | [140] |

| Lysinimicrobium flavum/Demequinaceae | Rhizosphere soil of mangrove | ||

| Lysinimicrobium gelatinilyticum/Demequinaceae | |||

| Lysinimicrobium iriomotense/Demequinaceae | |||

| Lysinimicrobium luteum/Demequinaceae | Soil of mangrove forest | ||

| Lysinimicrobium pelophilum/Demequinaceae | Mud of mangrove tidal flat | ||

| Lysinimicrobium rhizosphaerae/Demequinaceae | Rhizosphere soil of mangrove | ||

| Lysinimicrobium soli/Demequinaceae | Soil of mangrove forest | ||

| Lysinimicrobium subtropicum/Demequinaceae | Rhizosphere soil of mangrove | ||

| Micromonospora wenchangensis/Micromonosporaceae | Mangrove soil | Glucose-peptone-tryptone agar supplemented with 50 mg nystatin L−1, 50 mg cycloheximide L−1, 25 mg novobiocin L−1 and 20 mg nalidixic acid L−1 | [52] |

| Micromonospora zhanjiangensis/Micromonosporaceae | Mangrove soil | 1/10 ATCC 172 agar supplemented with nalidixic acid (10 µg mL−1), novobiocin (10 µg mL−1), nystatin (50 µg mL−1) and K2Cr2O7 (20 µg mL−1) | [141] |

| Micromonospora ovatispora/Micromonosporaceae | Mangrove soil | ATCC 172 agar | [142] |

| Micromonospora sediminis/Micromonosporaceae | Mangrove sediment | AV medium (1.0 g glucose, 1.0 g glycerol, 0.3 g L-arginine, 0.3 g K2HPO4, 0.2 g MgSO4.7H2O, 0.3 g NaCl, 18 g agar, artificial seawater added up to 1 L) | [42] |

| Micromonospora mangrovi/Micromonosporaceae | Mangrove soil | Glucose-peptone-tryptone agar (glucose 10 g, peptone 5 g, tryptone 3 g, NaCl 5 g, agar 15 g, ddH2O 1 L supplemented with 50 mg/L of nystatin, 50 mg/L of cycloheximide, 25 mg/L of novobiocin and 20 mg/L of nalidixic acid) | [143] |