Quality of Drinking Water Treated at Point of Use in Residential Healthcare Facilities for the Elderly

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Point of Use Water Treatment Devices

- ▪

- Microfiltered water dispensers (MWDs) (n = 20) with composite filters (EVERPURE). The filters consist of a disposable cartridge containing a membrane (0.5-micron pore size) made of polyethylene fibers and powdered activated carbon. The single-use cartridges are replaced once a year, and the circuits are disinfected twice a year with a stabilized aqueous solution of hydrogen peroxide. The devices examined had been in use for a mean of 41 months and dispensed around 35 L of water a day.

- ▪

- Reverse-osmosis water dispensers (ROWDs) (n = 18) with a sediment pre-filter, an activated carbon filter, an RO membrane (rated at 4 L/h), a 19 L storage tank, an activated carbon post-filter and a UV lamp. The filters (sediment pre-filter and 2 activated carbon filters) are replaced once a year, and the tank and the tubes are descaled and disinfected (with a multicomponent product based on acids and a stabilized aqueous solution of hydrogen peroxide) once a year. In addition, the devices all have a bypass mixer valve, whose function is to regulate the saline content of the dispensed water. The devices had a mean age of 71 months and dispensed around 35 L of water a day.

| Healthcare Facilities for the Elderly | Kind of Devices | Number of Devices | Number of Individuals Served | Age of Devices (in Months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C.M. | MWD | 4 | 102 | 54 |

| 2 | L.U. | MWD | 3 | 58 | 36, 36, 13 |

| 3 | S.N. | MWD | 2 | 25 | 12, 8 |

| 4 | M. | MWD | 1 | 20 | 20 |

| 5 | V.C. | MWD | 1 | 22 | 120 |

| 6 | G. | MWD | 1 | 10 | 8 |

| 7 | A. | MWD | 2 | 50 | 29 |

| 8 | F. | MWD | 1 | 31 | 101 |

| 9 | S.G. | MWD | 1 | 22 | 41 |

| 10 | M.T. | MWD | 1 | 15 | 10 |

| 11 | R.M. | MWD | 1 | 18 | 45 |

| 12 | B. | MWD | 2 | 32 | 41, 50 |

| 13 | V.O. | ROWD | 1 | 47 | 119 |

| 14 | S. | ROWD | 4 | 82 | 108 |

| 15 | P. | ROWD | 5 | 45 | 12 |

| 16 | R.A. | ROWD | 3 | 100 | 98 |

| 17 | R. | ROWD | 1 | 21 | 98 |

| 18 | V.F. | ROWD | 1 | 20 | 54 |

| 19 | S.B. | ROWD | 3 | 60 | 41, 91, 91 |

2.2. Sample Collection

- ▪

- Two samples of water from each device, 1 still unchilled water and 1 still chilled water.

- ▪

- One sample of municipal tap water entering the dispenser (generally from the nearest tap to the device).

2.3. Bacteriological Analyses

| Bacteriological Parameters | Microbial Criteria for Unbottled Water (Italian Regulation for Drinking Water) |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (EC) | 0/100 mL |

| Enterococci (ENT) | 0/100 mL |

| Total coliforms (TC) | 0/100 mL |

| Heterotrophic plate count (HPC) 22 °C | “no abnormal change” |

| Heterotrophic plate count (HPC) 37 °C * | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (SA) | 0/250 mL |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) and other non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria (NF-GNB) ** | |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) ** |

2.4. Physical and Chemical Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Bacteriological Characteristics of the Water

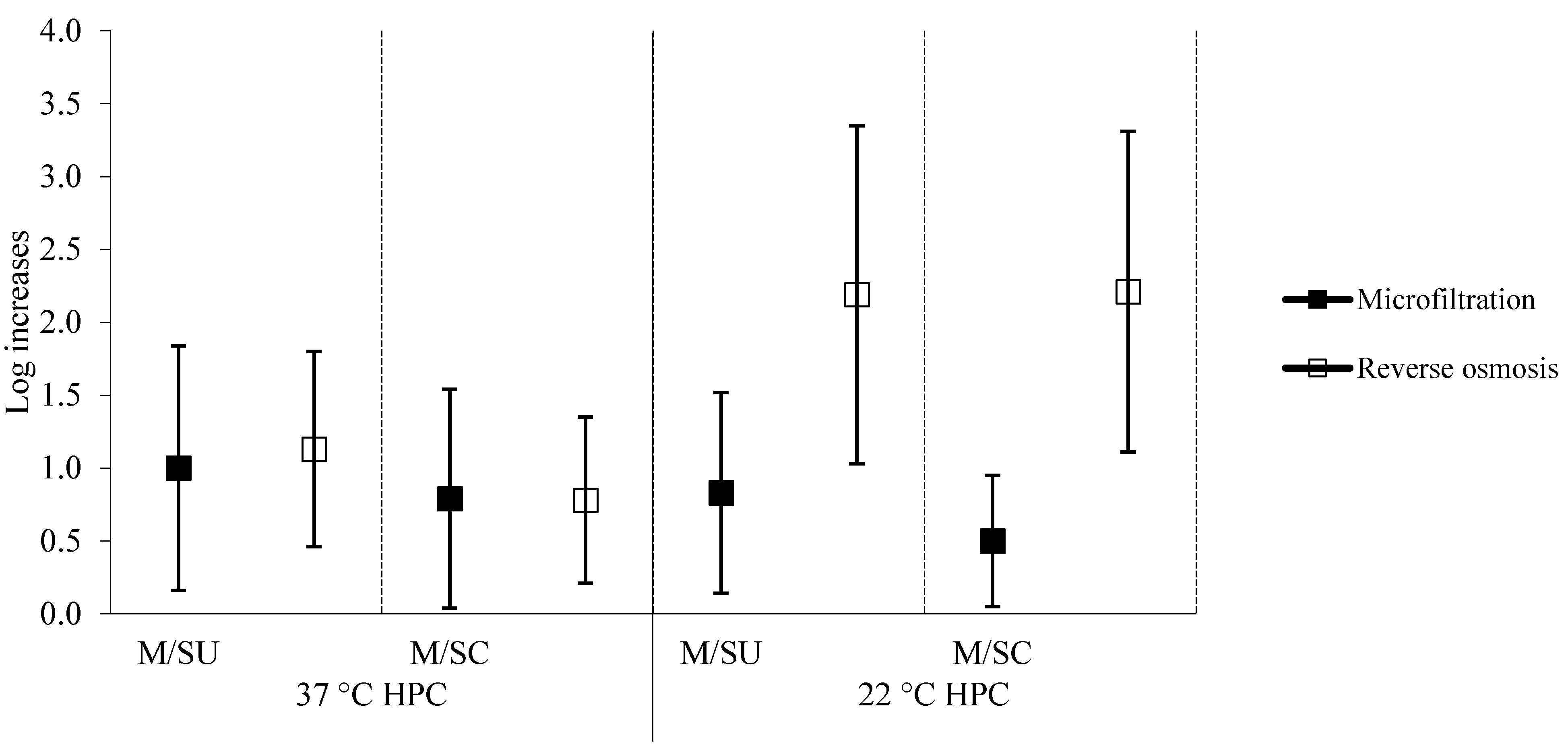

| 22 °C HPC (Log cfu/mL) | 37 °C HPC (Log cfu/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| MWDs | ||||

| municipal tap water | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.95 | 0.53 |

| still unchilled water | 0.91 | 0.54 | 1.57 | 0.54 |

| still chilled water | 0.71 | 0.51 | 1.37 | 0.50 |

| ROWDs | ||||

| municipal tap water | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.74 | 0.32 |

| still unchilled water | 1.45 | 0.46 | 1.58 | 0.52 |

| still chilled water | 1.44 | 0.50 | 1.32 | 0.59 |

3.2. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of the Water

| NF-GNB | Staphylococci (SA + CoNS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Number of Positive Samples | Range (cfu/250 mL) | Species | Number of Positive Samples | Range (cfu/250 mL) | |

| MWDs | ||||||

| M | P. aeruginosa | 2 | 1–2. | S. aureus | 1 | 1 |

| D. acidovorans | 1 | 2 | S. epidermidis | 1 | 1 | |

| Alc. xylosoxidans | 1 | 4 | S. haemolyticus | 1 | 1 | |

| C. testosteroni | 1 | 50 | S. hominis | 6 | 1–1. | |

| P. putida | 1 | 2 | S. saprophyticus | 1 | 2 | |

| SU | P. aeruginosa | 5 | 19–550 | S. epidermidis | 1 | 1 |

| P. aureofaciens | 1 | 24 | S. haemolyticus | 1 | 1 | |

| P. fluorescens | 2 | 5–7. | S. hominis | 1 | 1 | |

| Moraxella spp. | 1 | 1 | S. saprophyticus | 1 | 1 | |

| P. putida | 2 | 2–28. | S. xylosus | 2 | 1–1. | |

| S. maltophilia | 1 | 9 | ||||

| SC | P. aeruginosa | 7 | 1–573 | S. hominis | 2 | 1–1. |

| P. pickettii | 1 | 22 | S. saprophyticus | 1 | 1 | |

| P. stutzeri | 1 | 64 | S. warneri | 1 | 2 | |

| S. maltophilia | 2 | 10–1350 | ||||

| ROWDs | ||||||

| M | P. aeruginosa | 2 | 1–19. | S. conhii | 1 | 2 |

| D. acidovorans | 1 | 633 | ||||

| P. aureofaciens | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Moraxella spp. | 1 | 850 | ||||

| P. stutzeri | 1 | 1 | ||||

| SU | P. aureofaciens | 1 | 5 | |||

| P. fluorescens | 1 | 2 | ||||

| SC | P. aeruginosa | 3 | 4–10. | S. conhii | 2 | 1–2. |

| P. aureofaciens | 4 | 1–298 | S. epidermidis | 1 | 1 | |

| P. fluorescens | 1 | 2 | S. haemolyticus | 2 | 1–3. | |

| B. pseudomallei | 1 | 16 | S. warneri | 1 | 34 | |

| MWDs | ROWDs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Water temperature (°C) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 17.7 | 3.8 | 15.0 | 4.8 |

| still unchilled water | 21.8 | 4.0 | 17.8 | 3.5 |

| still chilled water | 7.9 | 3.9 | 8.2 | 2.6 |

| Residual chlorine (mg/L) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.10 |

| still unchilled water | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| still chilled water | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| pH value | ||||

| municipal tap water | 7.42 | 0.33 | 8.07 | 0.17 |

| still unchilled water | 7.40 | 0.27 | 6.87 | 0.44 |

| still chilled water | 7.42 | 0.27 | 6.83 | 0.42 |

| Conductivity (mS/cm) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 600 | 157 | 493 | 52 |

| still unchilled water | 602 | 153 | 69 | 63 |

| still chilled water | 597 | 150 | 67 | 62 |

| Calcium (mg/L) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 93.0 | 28.1 | 71.9 | 7.5 |

| still unchilled water | 90.8 | 26.7 | 7.0 | 8.9 |

| still chilled water | 92.4 | 30.8 | 6.1 | 7.2 |

| Sodium (mg/L) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 26.6 | 9.0 | 20.4 | 4.4 |

| still unchilled water | 26.2 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| still chilled water | 25.5 | 8.2 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| Total hardness (°F) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 29.1 | 8.9 | 23.5 | 2.9 |

| still unchilled water | 28.8 | 8.6 | 2.3 | 3.0 |

| still chilled water | 29.7 | 10.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Total dissolved solids at 180 °C (mg/L) | ||||

| municipal tap water | 406 | 115 | 311 | 45 |

| still unchilled water | 409 | 114 | 43 | 38 |

| still chilled water | 404 | 111 | 46 | 36 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anonymous. Sai cosa bere? Altroconsumo 2012, 261, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto Legislativo 2.02.2001, n. 31. Attuazione della direttiva 98/83/CE Relativa alla Qualità delle Acque Destinate al Consumo Umano (Implementation of Directive 98/83/EC on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption). G.U. della Repubblica Italiana n. 52, 3.03.2001. Available online: http://www.arpal.gov.it/images/stories/testi_normative/DLgs_31-2001.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2014).

- European Union. Council Directive 98/83/EC of 3 November 1998 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1998, L330, 32–54. [Google Scholar]

- Associazione Aqua Italia. Consumo di Acqua Potabile Presso la Popolazione Italiana. Available online: http://www.anima.it/sites/default/files/CRA2012.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2014).

- Zanetti, F.; de Luca, G.; Sacchetti, R. Control of bacterial contamination in microfiltered water dispensers (MWDs) by disinfection. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 128, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchetti, R.; de Luca, G.; Zanetti, F. Control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia contamination of microfiltered water dispensers with peracetic acid and hydrogen peroxide. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 132, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchetti, R.; de Luca, G.; Dormi, A.; Guberti, E.; Zanetti, F. Microbial quality of drinking water from microfiltered water dispensers. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aumeran, C.; Paillard, C.; Robin, F.; Kanold, J.; Baud, O.; Bonnet, R.; Souweine, B.; Traore, O. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida outbreak associated with contaminated water outlets in an oncohaematology paediatric unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 2007, 65, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trautmann, M.; Lepper, P.M.; Haller, M. Ecology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the intensive care unit and the evolving role of water outlets as a reservoir of the organism. Am. J. Infect. Control 2005, 33, S41–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lèvesque, B.; Simard, P.; Gauvin, D.; Gingras, S.; Dewailly, E.; Letarte, R. Comparison of the microbiological quality of water coolers and that of municipal water systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liguori, G.; Cavallotti, I.; Arnese, A.; Amiranda, C.; Anastasi, D.; Angelillo, I.F. Microbiological quality of drinking water from dispensers in Italy. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA; AWWA; WPCF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22th ed.; APHA; AWWA; WPCF: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- APAT; IRSA-CNR. Metodi Analitici per le Acque. 3020 Determinazione di Elementi Chimici Mediante Spettroscopia di Emissione con Sorgente al Plasma. Available online: http://www.irsa.cnr.it/Docs/Capitoli/1000.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2014).

- WHO. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, Fourth Edition. 2011. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241548151_eng.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2015).

- Chowdhuri, S. Heterotrophic bacteria in drinking water distribution system: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 184, 6087–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, J.T.; Marsh, P.D. Microbial biofilm formation in DUWS and their control using disinfectants. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.K.; Hu, J.Y. Assessment of the extent of bacterial growth in reverse osmosis system for improving drinking water quality. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard Subst. Environ. Eng. 2010, 45, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuel, C.M.; Nunes, O.C.; Melo, L.F. Unsteady state flow and stagnation in distribution systems affect the biological stability of drinking water. Biofouling 2010, 26, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, K.D.; Gerba, C.P. Risk assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in water. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 201, 71–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brooke, J.S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: An emerging global opportunistic pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 2–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verwej, P.E.; Meis, P.J.; Christmann, V.; van der Bor, M.; Melchers, W.J.; Hilderink, B.G.; Voss, A. Nosocomial outbreak of colonization and infection with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in preterm infants associated with contaminated tap water. Epidemiol. Infect. 1998, 120, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhini, E.; Weissmann, A.; Oren, I. Fulminant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia soft tissue infection in immunocompromised patients: An outbreak transmitted via tap water. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2002, 323, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervia, J.S.; Ortolano, G.A.; Canonica, F.P. Hospital tap water as a source of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1485–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotikanatis, K.; Backer, M.; Rosas-Garcia, G.; Hammerschlag, M.R. Recurrent intravascular-catheter-related bacteremia caused by Delftia acidovorans in a hemodialysis patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3418–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, J.L.; Wee, W.R.; Lee, J.H. Experience of Comamonas acidovorans keratitis with delayed onset and treatment response in immunocompromised cornea. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 22, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, Y.; Kitazawa, T.; Kamimura, M.; Tatsuno, K.; Ota, Y.; Yotsuyanagi, H. Pseudomonas putida bacteraemia in adult patients: Five case reports and a review of the literature. J. Infect. Chemother. 2011, 17, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.; Levi, K.; Baddal, B.; Turton, J.; Boswell, T.C. Spread of Pseudomonas fluorescens due to contaminated drinking water in a bone marrow transplant unit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 2093–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piette, A.; Verschraegen, G. Role of coagulase-negative staphylococci in human disease. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 134, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Calcium and Magnesium in Drinking Water: Public Health Significance. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563550_eng.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2015).

- Coudray, C.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Rambeau, M.; Tressol, J.C.; Gueux, E.; Mazur, A.; Rayssiguier, Y. The effect of aging on intestinal absorption and status of calcium, magnesium, zinc, and copper in rats: A stable isotope study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2006, 20, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galan, P.L.; Arnaud, M.J.; Czernichow, S.; Delabroise, A.M.; Preziosi, P.; Bertrais, S.; Franchisseur, C.; Maurel, M.; Favier, A.; Hercberg, S. Contribution of mineral waters to dietary calcium and magnesium intake in a French adult population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1658–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, MP. Magnesium and trace elements in the elderly: Intake, status and recommendations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2002, 6, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rasic-Milutinovic, Z.; Perunicic-Pekovic, G.; Jovanovic, D.; Gluvic, Z.; Cankovic-Kadijevic, M. Association of blood pressure and metabolic syndrome components with magnesium levels in drinking water in some Serbian municipalities. J. Water Health 2012, 10, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosanoff, A.; Weaver, C.M.; Rude, R.K. Suboptimal magnesium status in the United States: Are the health consequences underestimated? Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catling, A.; Abubakar, I.; Lake, I.R.; Swift, L.; Hunter, P.R. A systematic review of analytical observational studies investigating the association between cardiovascular disease and drinking water hardness. J. Water Health 2008, 6, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione (INRAN). Linee Guida per una Sana Alimentazione Italiana. Available online: http://nut.entecra.it/files/download/lineeguida/lineeguida_intro.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2015).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sacchetti, R.; De Luca, G.; Guberti, E.; Zanetti, F. Quality of Drinking Water Treated at Point of Use in Residential Healthcare Facilities for the Elderly. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 11163-11177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911163

Sacchetti R, De Luca G, Guberti E, Zanetti F. Quality of Drinking Water Treated at Point of Use in Residential Healthcare Facilities for the Elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(9):11163-11177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911163

Chicago/Turabian StyleSacchetti, Rossella, Giovanna De Luca, Emilia Guberti, and Franca Zanetti. 2015. "Quality of Drinking Water Treated at Point of Use in Residential Healthcare Facilities for the Elderly" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 9: 11163-11177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911163

APA StyleSacchetti, R., De Luca, G., Guberti, E., & Zanetti, F. (2015). Quality of Drinking Water Treated at Point of Use in Residential Healthcare Facilities for the Elderly. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(9), 11163-11177. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911163