A Comparative Study of the Role of Australia and New Zealand in Sustainable Dairy Competition in the Chinese Market after the Dairy Safety Scandals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Comparison of the Dairy Shares of Australia and New Zealand in the Chinese Market

3. Trade Competitiveness of Australia and New Zealand in the Chinese market

4. Model Specification

5. The Seemingly Unrelated Regression Model (SUR Model) and Data Classification

6. The Influence of Australia and New Zealand on China’s Dairy Import Market

6.1. The Effects of Relative Imports Prices

6.2. The Influence of China’s Joining the WTO

6.3. The Influence of the China Melamine Milk Scandal

6.4. The Effects of the Milk Quality Scandal of New Zealand

6.5. The Effects of the China-Australia FTA

6.6. The Food Safety Law in China Dairy Imports

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, H.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Z. Determinants of the competitive advantage of dairy supply chains: Evidence from the Chinese dairy industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Kong, J.; Sun, B. Safety evaluation of dairy cold chain logistics system based on the method of fuzzy fault tree analysis. Technol. Econ. Areas Commun. 2015, 17, 47–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Delaurentis, T. Quality control in food supply chain management: An analytical model and case study of the adulterated milk incident in China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.H.; Jukes, D. The national food safety control system of China-A systematic review. Food Control 2015, 32, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.M.; Remais, J.; Fung, M.C.; Xu, L.; Sun, S.S. Food supply and food safety issues in China. Lancet 2013, 381, 2044–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Bao, Y.X. Analysis of China’s dairy industry chain and value chain. Mod. Anim. Husb. 2012, 1, 8–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, M. Business ethics reflected in Sanlu milk incident. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, R.S.; Esmerino, E.A.; Rocha, R.S.; Pimentel, T.C.; Alvarenga, V.O.; Freitas, M.Q. Physical hazards in dairy products: Incidence in a consumer complaint website in Brazil. Food Control 2018, 86, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, N.; Wei, X. Dynamic Analysis on the characteristics of Dairy Trade in China. China Econ. Trade Guide J. 2011, 9, 58–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kita, J.; Máziková, K.; Grossmanová, M.; Kita, P. Trade practices of retail chains as far as the transaction cost analysis in the relationships manufacturer-retailer are concerned in the milk industry. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Starbird, S.A. Designing food safety regulations: The effect of inspection policy and penalties for non-compliance on food processors behavior. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2000, 25, 615–635. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.J.; Liu, Z.G. Study on safeguard measures of dairy products quality and safety in China. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2013, 41, 11494–11496. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.L. The present situation of milk station and it’s affection on milk qualification. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 44, 39–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, J.; Bai, J. Dual restraints and the influence on dairy industry in China: An empirical study by VAR model. Dairy Ind. 2016, 44, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, R.R.; Prakash, G.; Farooquie, J.A. A framework for traceability and transparency in the dairy supply chain networks. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 189, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Xu, H.; Lv, M.; Hu, D.; He, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y. Challenges to improve the safety of dairy products in China. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 76, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. China Dairy Yearbook 2003–2010; China Agricultural Publisher: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Chen, S.; Yan, Q.; Yao, Y.; Cao, Z. 2017 Diary industry Yearbook of China. Chin. Cow 2018, 3, 55–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, G.; Robertsonf, R.L. Domestic dairy policies and international market adjustment in a simplified model of world dairy products trade. J. Policy Model. 1993, 15, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoppola, M.; Raimondi, V.; Olper, A. The impact of EU trade preferences on the extensive and intensive margins of agricultural and food products. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yu, J.; Liu, F.; He, Z. Research on the influencing factors of Dairy Trade deficit in China: An empirical Analysis based on CMS Model. World Agric. 2015, 2, 128–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, M. Causes and problems of China’s Dairy products Import surge. Foreign Trade Pract. 2015, 1, 51–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F.Q.; Wu, X.L. China food safety hits the ‘gutter’. Food Control 2014, 41, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; Yu, H.Q.; Lv, W. Risk analysis of dairy safety incidents in China. Food Control 2018, 92, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrun, E.L.; Sellnow, T.L. China’s Response to the Melamine Crisis: A Case Study in Actional Legitimacy; The University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations ComTrade Database. Available online: http://comtrade.un.org/ (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- Huang, R. Analysis on the Import of Chinese Dairy products and its influencing factors. World Agric. 2016, 4, 173–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The impact of the implementation of China-New Zealand Free Trade area on Chinese Agriculture and Policy suggestions. Agric. Econ. Probl. 2011, 32, 106–109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Doole, G.J.; Romera, A.J. Trade-offs between profit, production, and environmental footprint on pasture-based dairy farms in the Waikato region of New Zealand. Agric. Syst. 2015, 141, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassells, S.M.; Meister, A.D. Cost and trade impacts of environmental regulations: Effluent control and the New Zealand dairy sector. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2001, 45, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, C.; Adduci, F.; Musto, M.; Paolino, R.; Freschi, P.; Pecora, G.; D’Adamo, C.; Valentini, V. Low vs. high “water footprint assessment” diet in milk production: A comparison between triticale and corn silage based diets. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2015, 27, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wu, N. Economic Effects of China—Australia FTA: An Analysis Based on SMART Model. Int. Econ. Trade Res. 2016, 32, 15–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Couillard, C.; Turkina, E. Trade Liberalisation: The Effects of Free Trade Agreements on the Competitiveness of the Dairy Sector. World Econ. 2015, 38, 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertö, I.; Hubbard, L.J. Revealed Comparative Advantage and Competitiveness in Hungarian Agri-Food Sectors. World Econ. 2003, 26, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B. Trade Liberalisation and “Revealed” Comparative Advantage. Manch. School 1965, 33, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini-Smaghi, L. Exchange rate variability and trade: Why is it so difficult to find any empirical relationship? Appl. Econ. 1991, 23, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broda, C.; Romalis, J. Identifying the relationship between trade and exchange rate volatility. In Commodity Prices and Markets, East Asia Seminar on Economics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. The role of China in the UK relative imports from three selected trading regions: The case of textile raw material industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armington, P. A theory of demand for products distinguished by place of production. IMF Staff Pap. 1969, 16, 170–201. [Google Scholar]

- Zellner, A. An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1962, 57, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, X. Generalized canonical correlation variables improved estimation in high dimensional seemingly unrelated regression models. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2017, 126, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Harmonized System (HS) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS 04 Dairy Products | ||||||||||

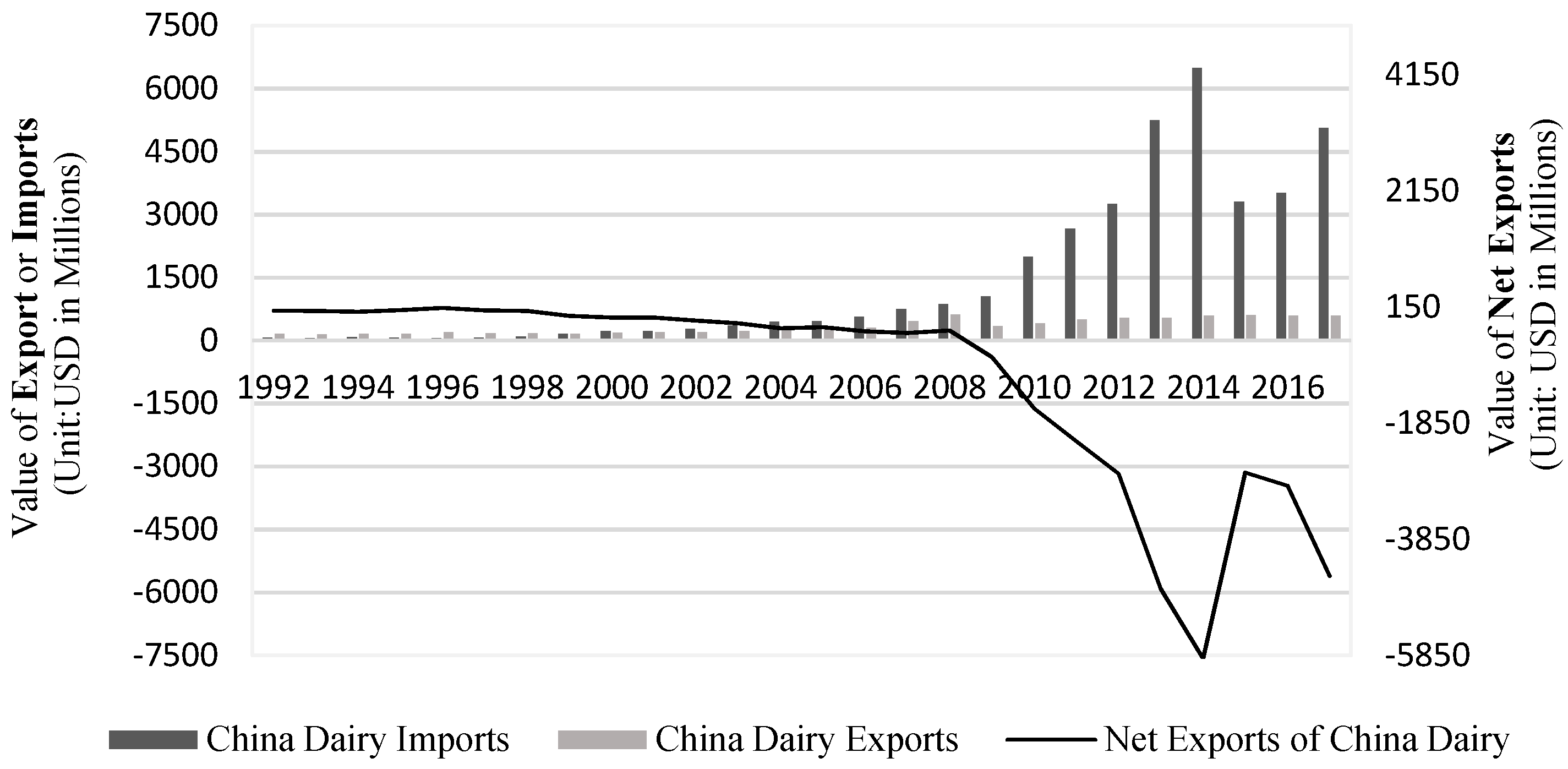

| 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2003 | 2005 | 2008 | 2010 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | |

| Exports | 158.8 | 162.2 | 187.9 | 221.6 | 267.4 | 872.8 | 404.6 | 544.8 | 606.1 | 588.2 |

| Imports | 68.8 | 63.6 | 217.9 | 349.8 | 461.8 | 621.0 | 2000.0 | 5245.2 | 3303.4 | 5070.0 |

| Net Export | 90.1 | 98.6 | −30.0 | −128.3 | −194.4 | −251.8 | −1595.5 | −4700.4 | −2697.4 | −4481.7 |

| Harmonized System (HS) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS 04 Dairy Products | ||||||||||

| 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2008 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | |||

| Sector 0401 | Milk and cream, not concentrated | EX | 15.7 | 17.1 | 20.1 | 22.6 | 29.6 | 16.0 | 24.1 | 20.7 |

| IM | 6.6 | 5.4 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 12.4 | 28.2 | 485.1 | 879.4 | ||

| Net EX | 9.1 | 11.7 | 11.2 | 16.8 | 17.2 | −12.2 | −461.0 | −858.7 | ||

| Sector 0402 | Milk and cream, concentrated | EX | 5.9 | 9.1 | 27.9 | 55.9 | 248.4 | 15.3 | 15.4 | 14.3 |

| IM | 34.1 | 29.0 | 115.7 | 235.4 | 401.4 | 1395.8 | 1529.1 | 2214.4 | ||

| Net EX | −28.2 | −19.9 | −87.8 | −179.5 | −153.0 | −1380.5 | −1513.7 | −2200.2 | ||

| Sector 0403 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yogurt | EX | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 3.7 |

| IM | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 27.9 | 66.8 | ||

| Net EX | −0.4 | −0.5 | −1.3 | −0.7 | −1.1 | −3.1 | −27.4 | −63.1 | ||

| Sector 0404 | Whey and product consisting of natural milk constituents | EX | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| IM | 15.8 | 19.4 | 80.0 | 157.4 | 312.0 | 344.8 | 524.3 | 666.1 | ||

| Net EX | −15.5 | −19.2 | −79.7 | −156.9 | −307.2 | −344.0 | −524.2 | −665.7 | ||

| Sector 0405 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; dairy spread | EX | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 17.2 | 9.7 | 4.0 | 7.6 |

| IM | 3.0 | 1.3 | 4.7 | 31.8 | 59.2 | 91.4 | 265.5 | 499.5 | ||

| Net EX | −2.9 | −1.1 | −4.4 | −31.7 | −42.1 | −81.7 | −261.5 | −491.9 | ||

| Sector 0406 | Cheese and curd | EX | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| IM | 1.5 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 26.4 | 53.8 | 105.4 | 348.1 | 497.5 | ||

| Net EX | −1.5 | −1.8 | −2.7 | −24.5 | −52.3 | −104.5 | −347.1 | −496.3 | ||

| Year | Harmonized System (HS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS 04 Dairy Products | ||||||

| Australia | New Zealand | Sum | ||||

| Value | % in World Dairy Imports | Value | % in World Dairy Imports | Value | % in World Dairy Imports | |

| 1992 | 4.09 | 6.64% | 6.92 | 11.23% | 11.01 | 17.64% |

| 1995 | 5.07 | 8.79% | 6.39 | 11.08% | 11.46 | 19.79% |

| 2000 | 27.34 | 12.76% | 85.69 | 39.99% | 113.03 | 52.76% |

| 2005 | 48.76 | 10.67% | 221.91 | 48.56% | 270.67 | 59.67% |

| 2008 | 126.35 | 14.48% | 321.11 | 36.80% | 447.46 | 51.27% |

| 2010 | 127.74 | 6.52% | 1299.92 | 66.35% | 1427.66 | 72.52% |

| 2015 | 263.53 | 8.49% | 1749.68 | 56.37% | 2013.21 | 64.49% |

| 2017 | 369.28 | 7.80% | 2771.96 | 58.55% | 3141.24 | 66.80% |

| Code | Sector | Countries | Harmonized System (HS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS 04 Dairy Products | |||||||||

| 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 | |||

| HS0401 | Milk and cream, not concentrated | Australia | 0.49% | 1.51% | 2.47% | 0.15% | 0.07% | 1.96% | 1.36% |

| New Zealand | 0.03% | 0.27% | 0.67% | 0.70% | 0.79% | 3.47% | 7.45% | ||

| HS0402 | Milk and cream, concentrated | Australia | 3.09% | 2.56% | 6.17% | 5.72% | 4.36% | 3.27% | 3.77% |

| New Zealand | 3.34% | 7.67% | 35.56% | 39.11% | 56.84% | 36.25% | 32.57% | ||

| HS0403 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yogurt | Australia | 0.03% | 0.46% | 0.07% | 0.07% | 0.05% | 0.06% | 0.04% |

| New Zealand | 0.04% | 0.06% | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.01% | 0.29% | 0.21% | ||

| HS0404 | Whey and product consisting of natural milk constituents | Australia | 1.76% | 1.56% | 3.23% | 2.38% | 0.47% | 0.39% | 0.19% |

| New Zealand | 5.78% | 1.25% | 0.47% | 1.61% | 1.04% | 0.44% | 0.28% | ||

| HS0405 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; dairy spread | Australia | 0.14% | 0.46% | 0.08% | 0.53% | 0.36% | 0.34% | 0.21% |

| New Zealand | 0.58% | 0.59% | 1.90% | 4.11% | 3.67% | 6.44% | 8.21% | ||

| HS0406 | Cheese and curd | Australia | 0.43% | 1.40% | 0.52% | 1.71% | 1.07% | 1.96% | 1.72% |

| New Zealand | 0.30% | 0.04% | 0.68% | 2.51% | 2.53% | 4.90% | 4.82% | ||

| Code | Sector | Country | 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS04 | Dairy product | Australia | 0.834 | 0.818 | 0.943 | 0.924 | 0.934 | 0.880 | 0.916 |

| New Zealand | 0.996 | 0.985 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | ||

| HS0401 | Milk and cream, not concentrated | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.867 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040110 | Fat content ≤1% | Australia | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.829 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | 1.000 | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040120 | Fat content >1% and ≤6% | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.810 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040130 | Fat content >6% | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | --- | --- | ||

| HS040140 | Fat content >6% and ≤10% | Australia | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040150 | Fat content >10% | Australia | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | ||

| HS0402 | Milk and cream, concentrated | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.991 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040210 | Fat content ≤1.5% | Australia | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040221 | Not containing added sugar, fat content >1.5% | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040229 | Containing added sugar, fat content >1.5% | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040291 | Not containing added sugar, other than in solid forms | Australia | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.886 | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | ||

| HS040299 | Containing added sugar, other than in solid forms | Australia | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.703 | 0.726 | 0.990 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | ||

| HS0403 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yogurt | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.625 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040310 | Yogurt | Australia | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040390 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream | Australia | 1.000 | --- | 1.000 | 0.138 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS0404 | Whey and product consisting of natural milk constituents | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040410 | Whey | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040490 | Natural milk (excluding whey) | Australia | 1.000 | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | --- | ---- | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS0405 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; dairy spread | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | --- | 1.000 | ||

| HS040500 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | -- | --- | -- | -- | --- |

| New Zealand | 1.000 | 1.000 | -- | --- | -- | -- | --- | ||

| HS040510 | Derived from milk, butter | Australia | -- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | -- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040520 | Dairy spreads | Australia | -- | --- | -- | 1.000 | -- | -- | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | -- | --- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| HS040590 | Fats and oils from derived from milk | Australia | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| New Zealand | -- | -- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS0406 | Cheese and curd | Australia | 0.961 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.979 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | -- | 0.558 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040610 | Fresh cheese, not fermented and curd | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | -- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040620 | Cheese of all kinds, grated or powdered | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | -- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040630 | Cheese, processed | Australia | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HS040640 | Cheese, blue-veined | Australia | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | --- | --- |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | 1.000 | 1.000 | --- | --- | ||

| HS040690 | Cheese (not grated, powdered or processed) | Australia | 0.942 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.958 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.974 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Code | Sector | Countries | 1992 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS04 | Dairy product | Australia | 0.001 | --- | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| New Zealand | 0.266 | 0.152 | 0.785 | 1.138 | 1.582 | 1.186 | 1.302 | ||

| HS0401 | Milk and cream, not concentrated | Australia | 0.126 | 0.829 | 0.962 | 0.056 | 0.090 | 1.097 | 1.213 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.333 | 0.174 | 1.046 | 1.125 | 3.002 | 3.230 | ||

| HS040110 | Fat content ≤1% | Australia | --- | 6.783 | 0.939 | 0.203 | 0.102 | 1.185 | 2.100 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.050 | --- | --- | 1.377 | 2.162 | 2.035 | ||

| HS040120 | Fat content >1% and ≤6% | Australia | 0.098 | 0.448 | 1.268 | 0.040 | 0.105 | 1.178 | 1.169 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.902 | 0.202 | 0.193 | 0.265 | 2.645 | 3.039 | ||

| HS040130 | Fat content >6% | Australia | 0.250 | 0.791 | 0.057 | 0.036 | 0.044 | --- | --- |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.032 | 0.124 | 2.707 | 2.599 | --- | --- | ||

| HS040140 | Fat content >6% and ≤10% | Australia | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.920 | 0.779 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3.351 | 2.877 | ||

| HS040150 | Fat content >10% | Australia | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.485 | 0.662 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3.359 | ||

| HS0402 | Milk and cream, concentrated | Australia | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.369 | 0.237 | 0.426 | 0.361 | 0.991 |

| New Zealand | 0.198 | 0.224 | 1.553 | 1.885 | 2.469 | 1.486 | 1.585 | ||

| HS040210 | Fat content ≤1.5% | Australia | --- | --- | 0.400 | 0.307 | 0.290 | 0.317 | 0.761 |

| New Zealand | 0.065 | 0.154 | 1.113 | 1.812 | 1.336 | 1.793 | 1.448 | ||

| HS040221 | Not containing added sugar, fat content >1.5% | Australia | 0.016 | 0.056 | 0.376 | 0.174 | 0.589 | 0.476 | 1.443 |

| New Zealand | 0.253 | 0.246 | 1.796 | 1.929 | 2.846 | 1.407 | 1.597 | ||

| HS040229 | Containing added sugar, fat content >1.5% | Australia | 0.026 | 0.093 | 0.016 | 0.182 | 0.672 | 0.922 | 1.945 |

| New Zealand | 0.474 | 0.496 | 1.107 | 1.403 | 3.424 | 0.999 | 4.046 | ||

| HS040291 | Not containing added sugar, other than in solid forms | Australia | --- | 0.015 | 0.002 | 0.474 | --- | 0.187 | 0.214 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 0.451 | ||

| HS040299 | Containing added sugar, other than in solid forms | Australia | --- | 0.055 | 0.386 | --- | 0.060 | 0.081 | 0.948 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | 0.022 | --- | --- | 4.428 | ||

| HS0403 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yogurt | Australia | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.063 | 0.094 | 0.063 | 0.109 |

| New Zealand | 0.039 | 0.685 | 0.140 | 0.087 | 0.574 | 0.474 | 0.405 | ||

| HS040310 | Yogurt | Australia | --- | 0.005 | 0.167 | 0.195 | 0.209 | 0.097 | 0.136 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.054 | 0.439 | 1.253 | 0.750 | 0.931 | 0.286 | ||

| HS040390 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream | Australia | 0.005 | --- | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.045 | 0.036 | 0.050 |

| New Zealand | 0.041 | 0.721 | 0.134 | 0.058 | 0.573 | 0.386 | 0.406 | ||

| HS0404 | Whey and product consisting of natural milk constituents | Australia | 1.661 | 2.594 | 2.056 | 0.908 | 0.592 | 0.651 | 0.604 |

| New Zealand | 22.417 | 1.277 | 0.780 | 0.497 | 0.638 | 0.162 | 0.183 | ||

| HS040410 | Whey | Australia | 0.425 | 3.675 | 2.628 | 0.975 | 0.597 | 0.665 | 0.606 |

| New Zealand | 3.232 | 2.649 | 3.302 | 8.245 | 6.323 | 0.952 | 1.025 | ||

| HS040490 | Natural milk (excluding whey) | Australia | 4.443 | --- | 0.232 | 0.348 | --- | --- | 0.509 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | 0.045 | 0.106 | 0.267 | 0.120 | 0.109 | ||

| HS0405 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; dairy spread | Australia | 0.012 | 0.105 | 0.031 | 0.048 | 0.071 | 0.214 | 0.438 |

| New Zealand | 0.272 | 0.081 | 0.060 | 0.564 | 0.437 | 0.791 | 0.862 | ||

| HS040500 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk | Australia | 0.012 | 0.105 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| New Zealand | 0.272 | 0.081 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| HS040510 | Derived from milk, butter | Australia | --- | --- | 0.061 | 0.103 | 0.087 | 0.317 | 0.622 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | 0.049 | 0.427 | 0.394 | 1.086 | 1.031 | ||

| HS040520 | Dairy spreads | Australia | --- | --- | --- | 0.015 | --- | --- | 0.007 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| HS040590 | Fats and oils from derived from milk | Australia | --- | --- | --- | 0.004 | 0.050 | --- | --- |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | 0.083 | 0.899 | 0.506 | 0.448 | 0.643 | ||

| HS0406 | Cheese and curd | Australia | 0.010 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.095 | 0.111 | 0.275 | 0.401 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.007 | 0.038 | 0.290 | 0.424 | 0.804 | 0.802 | ||

| 0HS040610 | Fresh cheese, not fermented and curd | Australia | 0.037 | 0.225 | 0.001 | 0.049 | 0.125 | 0.297 | 0.502 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | 0.136 | 0.570 | 1.542 | 2.301 | 1.928 | ||

| HS040620 | Cheese of all kinds, grated or powdered | Australia | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.063 | 0.044 | 0.075 | 0.141 |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | 0.146 | 1.721 | 1.397 | 1.813 | 1.530 | ||

| HS040630 | Cheese, processed | Australia | 0.005 | 0.026 | 0.008 | 0.149 | 0.147 | 0.124 | 0.184 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.024 | 0.020 | 0.172 | 0.412 | 0.789 | 0.916 | ||

| HS040640 | Cheese, blue-veined | Australia | --- | --- | --- | 0.021 | 0.020 | --- | --- |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | 0.291 | 0.000 | --- | --- | ||

| HS040690 | Cheese (not grated, powdered or processed) | Australia | 0.012 | 0.034 | 0.006 | 0.083 | 0.100 | 0.317 | 0.393 |

| New Zealand | --- | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.045 | 0.028 | 0.146 | 0.188 |

| HS 04 Dairy Product | |

|---|---|

| HS0401; | Milk and Cream, not concentrated, not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter; |

| HS040110 | Fat content, by weight, not exceeding 1%; |

| HS040120 | Fat content, by weight, exceeding 1% but not exceeding 6%; |

| HS040130 | Fat content, by weight, exceeding 1% exceeding 6%; |

| HS040140 | Fat content, by weight, exceeding 6% but not exceeding 10%; |

| HS040150 | Fat content, by weight, exceeding 10%; |

| HS0402 | Milk and Cream, concentrated or containing added sugar or other sweetening matter; |

| HS040210 | In powder, granules or other solid forms, of a fat content not exceeding 1.5% (by weight); |

| HS040221 | Not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter, in powder, granules or other solid forms, of a fat content exceeding 1.5% (by weight); |

| HS040229 | In powder, granules or other solid forms, of a fat content exceed 1.5% (by weight); |

| HS040291 | Not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter, other than in powder granules or other solid forms; |

| HS040299 | Other than in powder granules or other solid forms; |

| HS0403 | Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yoghurt, kephir, fermented or acidified milk or cream, whether or not concentrated, containing added sugar, sweetening matter, flavoured or added fruit or cocoa; |

| HS040310 | Yoghurt; |

| HS040390 | Buttermilk, curdled milk or cream, kephir, fermented or acidified milk or cream; |

| HS0404 | Whey and product consisting of natural milk constituents, whether or not containing added sugar or other sweetening matter, not elsewhere specified or included; |

| HS040410 | Whey; |

| HS040490 | Natural milk constituents (excluding whey); |

| HS0405 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; dairy spreads; |

| HS040500 | Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; |

| HS040510 | Derived from milk, butter; |

| HS040520 | Dairy spreads; |

| HS040590 | Fats and oils derived from milk (other than butter or dairy spreads); |

| HS0406 | Cheese and curd; |

| HS040610 | Fresh cheese (including whey cheese), not fermented, and curd; |

| HS040620 | Cheese of all kinds, grated or powdered; |

| HS040630 | Cheese, processed (not grated or powered); |

| HS040640 | Blue-veined and other cheese containing veins produced by penicillium roqueforti (not grated, powdered or processed); |

| HS040690 | Cheese (not grated, powdered or processed); |

| Variables | Impact Countries | Constant | R2 | Observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | |||||||||||

| HS0401 Milk and cream, not concentrated, not containing added sugar | Australia | 5.109 *** (3.47) | −2.635 *** (3.16) | −2.764 (1.15) | 3.265 *** (3.34) | 0.016 (0.00) | 0.432 (0.11) | 8.712 ** (2.04) | 0.6276 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 6.438 *** (3.22) | −4.773 ** (2.31) | −4.455 ** (1.98) | −1.351 ** (2.04) | 1.356 (0.03) | −1.220 (0.02) | −0.532 (0.01) | 0.6311 | 26 | ||

| HS040110 Fat content ≤1% | Australia | 9.294 *** (2.79) | −1.176 ** (2.38) | 5.178 (1.60) | 0.137 (0.04) | −0.474 (0.10) | 0.967 (0.17) | −1.254 (0.19) | 0.5619 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 7.770 *** (3.57) | −4.900 *** (4.91) | −3.406 (1.05) | −3.203 ** (2.21) | 48.406 (0.08) | −4.991 (0.06) | 85.680 (0.11) | 0.7672 | 26 | ||

| HS040120 Fat content >1% and ≤6% | Australia | 8.903 *** (2.36) | −1.815 *** (3.54) | −1.378 (0.96) | 2.283 *** (3.05) | 2.358 (1.00) | −0.262 (0.09) | 5.266 (1.73) | 0.5301 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 3.492 *** (4.05) | −6.851 *** (5.96) | −6.411 ** (2.14) | 2.077 (0.06) | 6.940 (0.15) | −5.479 (0.10) | 4.110 (0.07) | 0.5708 | 26 | ||

| HS040130 Fat content >6% | Australia | 3.27 ** (2.31) | −1.85 ** (2.34) | 5.71 (0.17) | 3.191 * (1.76) | 1.375 (0.25) | 0.165 (0.43) | 12.400 (2.15) | 0.5593 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 2.877 *** (2.63) | −2.705 *** (12.12) | −2.632 *** (3.64) | −1.203 *** (3.52) | 0.556 (1.32) | 0.155 (1.33) | 1.668 (0.13) | 0.7222 | 26 | ||

| HS040140 Fat content >6% and ≤10% | Australia | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| HS040150 Fat content >10% | Australia | 6.139 *** (3.24) | −1.490 ** (2.16) | −2.331 (0.35) | 2.135 (0.989) | 0.435 (1.56) | −3.752 (1.22) | 4.350 (1.45) | 0.6928 | 20 | |

| New Zealand | 8.64 *** (9.37) | −3.485 *** (7.75) | −1.536 (0.75) | 1.633 (0.763) | 0.719 *** (13.21) | −0.780 *** (10.37) | 2.545 (0.758) | 0.5073 | 20 | ||

| Variables | Impact Countries | Constant | R2 | Observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | |||||||||||

| HS0402 Milk and cream, concentrated or containing added sugar | Australia | 9.269 ** (2.63) | −1.654 ** (2.09) | −0.200 (1.46) | 1.609 *** (3.17) | 1.002 ** (2.09) | −1.708 *** (2.84) | 17.011 (3.24) | 0.7176 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 6.582 (1.24) | −3.833 *** (3.18) | −4.331 *** (2.93) | −3.097 *** (3.06) | −0.069 (0.03) | 0.073 (0.03) | −0.592 (0.19) | 0.4385 | 26 | ||

| HS040210 Fat content ≤1.5% | Australia | 12.991 *** (2.59) | −0.735 *** (2.80) | −4.927 *** (3.69) | 4.068 (0.88) | 6.941 (1.05) | −6.744 (0.92) | 6.487 (0.73) | 0.6435 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 20.778 * (177) | −1.214 *** (5.98) | −7.779 (2.68) | −1.428 ** (2.13) | 0.491 (0.10) | 0.293 (0.06) | 0.173 (0.03) | 0.7533 | 26 | ||

| HS040221 Not containing added sugar Fat content >1.5% | Australia | 14.305 ** (2.25) | −1.985 *** (5.22) | 1.163 (0.14) | 2.513 ** (2.40) | 3.326 (0.25) | −1.780 (0.71) | 38.408 (2.39) | 0.5312 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 10.437 ** (2.25) | −3.507 ** (2.18) | −2.814 *** (3.79) | −1.326 ** (2.03) | −0.078 (0.06) | −0.130 (0.10) | −0.404 (0.24) | 0.5770 | 26 | ||

| HS040229 Containing added sugar, fat content >1.5% | Australia | 5.212 ** (2.04) | −2.220 ** (2.36) | 1.904 (0.32) | 12.464 (1.84) | 273.851 (1.62) | −4.060 (2.71) | 22.458 (1.04) | 0.5535 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 6.144 (1.61) | −5.234 *** (6.45) | −2.990 (0.73) | −1.043 ** (2.29) | −0.331 (0.06) | 5.366 (0.96) | −0.287 (0.04) | 0.6113 | 26 | ||

| HS040291 Not containing added sugar, other than in solid forms | Australia | 6.215 *** (3.11) | −0.801 *** (7.09) | −0.884 (0.10) | −0.764 (0.09) | 8.552 (0.77) | −1.376 (0.85) | −0.964 (0.06) | 0.7435 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 3.568 ** (2.06) | −3.702 *** (3.87) | −3.039 (0.79) | 2.742 (0.53) | 1.908 *** (2.73) | 0.51 (0.82) | 28.840 (0.30) | 0.7990 | 26 | ||

| HS040299 Containing added sugar, other than in solid forms | Australia | 6.933 (1.13) | −2.598 *** (4.35) | −0.807 (0.00) | −6.593 (0.03) | 1.89 *** (3.68) | −1.42 (3.40) | 7.426 (1.56) | 0.8722 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 5.301 *** (3.71) | −6.616 ** (2.32) | 0.750 (0.04) | −2.405 *** (2.75) | −7.080 (0.94) | 1.536 (1.43) | 22.87 (0.536) | 0.7325 | 26 | ||

| Variables | Impact Countries | Constant | R2 | Observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | |||||||||||

| HS0403 Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream, yogurt | Australia | 16.583 (1.21) | −2.759 *** (3.10) | −6.304 (1.63) | 1.874 (0.43) | 10.771 (1.72) | 6.024 (0.87) | 3.091 (0.36) | 0.6696 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 34.583 ** (2.08) | −6.801 *** (5.87) | −2.245 *** (2.62) | 3.990 (0.78) | −19.804 (0.85) | 3.025 (0.12) | −48.870 (1.67) | 0.7604 | 26 | ||

| HS040310 Yogurt | Australia | 70.147 ** (2.25) | −1.086 *** (3.97) | −3.426 (0.36) | 11.280 (0.46) | −0.493 (0.01) | 1.413 (0.28) | −4.051 (0.09) | 0.5753 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 13.678 ** (2.55) | −4.329 *** (5.83) | −2.538 ** (2.18) | 9.414 (0.34) | −3.682 (0.78) | 1.396 (0.41) | −47.205 (0.85) | 0.7585 | 22 | ||

| HS040390 Buttermilk, curdled milk and cream | Australia | 28.176 * (1.84) | −1.787 ** (2.26) | 1.101 (1.09) | 4.021 (0.26) | −5.144 (0.27) | 3.362 (0.01) | 3.594 (0.81) | 0.6579 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 13.916 *** (2.98) | −3.210 *** (3.25) | −2.423 ** (2.56) | −8.376 (0.16) | −4.876 (0.66) | 1.081 (0.13) | −108.876 (1.10) | 0.6949 | 26 | ||

| Variables | Impact Countries | Constant | R2 | Observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | |||||||||||

| HS0404 Whey and product consisting of natural milk constituents | Australia | 10.579 ** (2.13) | −1.412 *** (5.12) | 1.618 (0.44) | 2.151 *** (5.83) | 3.851 *** (4.78) | −8.403 (1.26) | 12.856 ** (2.53) | 0.9058 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 7.039 *** (4.49) | −3.795 *** (4.04) | 2.260* (1.90) | −3.625 ** (2.56) | 36.034 (1.08) | −1.927 (0.30) | 17.241 ** (2.37) | 0.7249 | 26 | ||

| HS040410 Whey | Australia | 5.212 ** (2.40) | −1.092 *** (3.30) | 1.905 (0.48) | 2.209 *** (5.25) | 1.110 *** (4.41) | −4.008 (0.54) | 17.920 ** (2.26) | 0.8953 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 4.354 (1.46) | −4.682 *** (5.85) | 3.348 ** (2.15) | −7.001 *** (2.70) | 2.204 *** (3.11) | −1.315* (1.80) | 38.654 *** (2.58) | 0.6759 | 26 | ||

| HS040490 Natural milk (excluding whey) | Australia | 1.888 ** (2.01) | −1.143 *** (4.07) | 12.383 (0.03) | 1.041 *** (3.08) | −975.381 (1.47) | −5.211 (0.85) | −3.224 *** (17.24) | 0.5576 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 3.189 *** (7.45) | −3.859 *** (2.46) | 0.989 (0.64) | −5.267 (1.10) | −33.745 (0.05) | 2.211 (0.04) | −30.767 (0.03) | 0.6416 | 19 | ||

| Variables | Impact Countries | Constant | R2 | Observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | |||||||||||

| HS0405 Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk; dairy spread | Australia | 7.671 ** (2.07) | −1.305 *** (3.73) | 2.646 (0.56) | 3.266 (0.64) | 2.227 (2.82) | −2.285 (0.30) | 1.700 (0.17) | 0.6161 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 1.542 (1.44) | −5.854 *** (2.71) | −2.978 *** (3.08) | −0.104 ** (2.27) | −0.083 (0.05) | −0.022 (0.01) | −0.122 (0.06) | 0.6675 | 26 | ||

| HS040500 Butter and other fats and oils derived from milk | Australia | 2.351 ** (2.19) | −1.435 ** (2.53) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 6 | |

| New Zealand | 3.102 (1.52) | −2.324 *** (2.66) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 6 | ||

| HS040510 Derived from milk, butter | Australia | 14.429 *** (6.63) | −0.679 *** (4.71) | 6.783 (1.57) | −3.784 (0.96) | 1.400 (2.20) | 2.180 (0.36) | 0.130 (0.02) | 0.6443 | 22 | |

| New Zealand | 10.176 *** (3.13) | −1.806 *** (5.31) | −0.618 *** (3.27) | −0.112 ** (2.57) | −0.130 (0.48) | 0.029 (0.10) | −0.130 (0.35) | 0.5406 | 22 | ||

| HS040520 Dairy spreads | Australia | 9.377 *** (5.58) | −2.086 ** (2.29) | −2.974 (1.18) | −11.902 (0.93) | 1.661 (4.74) | 1.242 (0.27) | 0.862 (0.66) | 0.9123 | 22 | |

| New Zealand | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | ||

| HS040590 Fats and oils derived from milk | Australia | 8.752 *** (2.83) | −1.961 *** (5.08) | −6.085 (0.64) | 1.385 ** (2.54) | 3.737 (6.89) | --- | --- | 0.8783 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 3.464 (1.13) | −2.102 ** (2.08) | 2.710 (0.53) | 1.453 (0.82) | 1.212 (1.23) | 3.012 (0.83) | −0.035 (0.04) | 0.6735 | 24 | ||

| Variables | Impact Countries | Constant | R2 | Observations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | |||||||||||

| HS0406 Cheese and curd | Australia | 1.745 (1.56) | −2.387 *** (2.89) | −0.207 (0.24) | 0.567 (0.73) | −0.365 (0.35) | 1.129 (1.00) | 0.335 (0.24) | 0.6184 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | −4.021 *** (2.88) | −1.242 ** (2.07) | −6.353 (0.77) | −0.783 ** (2.10) | 1.547 (0.13) | −0.310 (0.02) | 0.602 * (1.89) | 0.7606 | 26 | ||

| HS040610 Fresh cheese, not fermented and curd | Australia | 25.925 *** (3.25) | −2.418 *** (3.57) | 4.997 (0.96) | −74.341 (0.12) | 1.656 (0.38) | 2.138 (0.03) | −21.676 (0.02) | 0.6557 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 26.804 ** (2.11) | −1.904 *** (5.09) | −5.138 ** (2.12) | −1.1397 ** (2.18) | −0.554 (0.06) | −0.107 (0.01) | −0.828 (0.07) | 0.5854 | 26 | ||

| HS040620 Cheese of all kinds, grated or powdered | Australia | 15.917 *** (2.61) | −1.968 ** (2.31) | −5.917* (1.74) | 10.432 (0.28) | 1.129 (0.32) | 6.259 (1.23) | 25.582 (0.37) | 0.6129 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 11.551 *** (4.69) | −1.969 ** (2.19) | 5.671 (0.54) | −1.834 (2.61) | 0.162 (0.01) | −0.055 (0.22) | 0.116 * (1.81) | 0.5890 | 24 | ||

| HS040630 Cheese, processed | Australia | −0.470 (1.13) | −5.262 ** (2.45) | 2.724 (0.95) | −5.631* (1.91) | 0.406 (0.10) | 5.091 (1.11) | −1.343 (0.23) | 0.5954 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | −2.985 ** (2.07) | −2.013 *** (4.32) | 2.540 (0.05) | 4.322 (0.09) | 7.518 (0.10) | 8.177 (0.10) | 0.730 * (1.79) | 0.5386 | 26 | ||

| HS040640 Cheese, blue-veined | Australia | −64.547 (1.08) | −5.547 ** (2.08) | 1.003 (0.69) | −59.546 (0.37) | --- | --- | --- | 05722 | 6 | |

| New Zealand | −24.992 ** (2.09) | −7.503 *** (6.11) | 3.97* (1.81) | −10.526 (0.17) | --- | --- | --- | 0.6306 | 6 | ||

| HS040690 Cheese (not grated, powdered or processed) | Australia | 1.881 (1.63) | −1.206 *** (5.206) | 0.141 (0.23) | −0.393 (0.56) | −0.397 (0.40) | 0.314 (0.29) | −0.925 (0.69) | 0.5253 | 26 | |

| New Zealand | 2.911 *** (2.82) | −2.369 *** (3.75) | −7.426 *** (4.73) | 0.232 *** (3.12) | 2.818 (0.31) | −0.499 (0.05) | 4.192 (0.34) | 0.5946 | 26 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Wu, Y. A Comparative Study of the Role of Australia and New Zealand in Sustainable Dairy Competition in the Chinese Market after the Dairy Safety Scandals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122880

Xu J, Wu Y. A Comparative Study of the Role of Australia and New Zealand in Sustainable Dairy Competition in the Chinese Market after the Dairy Safety Scandals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(12):2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122880

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Junqian, and Yuanyuan Wu. 2018. "A Comparative Study of the Role of Australia and New Zealand in Sustainable Dairy Competition in the Chinese Market after the Dairy Safety Scandals" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 12: 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122880

APA StyleXu, J., & Wu, Y. (2018). A Comparative Study of the Role of Australia and New Zealand in Sustainable Dairy Competition in the Chinese Market after the Dairy Safety Scandals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(12), 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122880