Does Walkability Contribute to Geographic Variation in Psychosocial Distress? A Spatial Analysis of 91,142 Members of the 45 and Up Study in Sydney, Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Area

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data

2.4. Outcome Variable

2.5. Study Variable

- Residential dwelling density—the number of residential dwellings per square kilometre of residential land use

- Intersection density—the number of intersections with three or more roads per square kilometre of total land area

- Land use mix—the entropy of residential, commercial, industrial, recreational and other land uses.

2.6. Covariates

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical and Data Access Statements

3. Results

3.1. Walkability

3.2. Prevalence of Psychosocial Distress

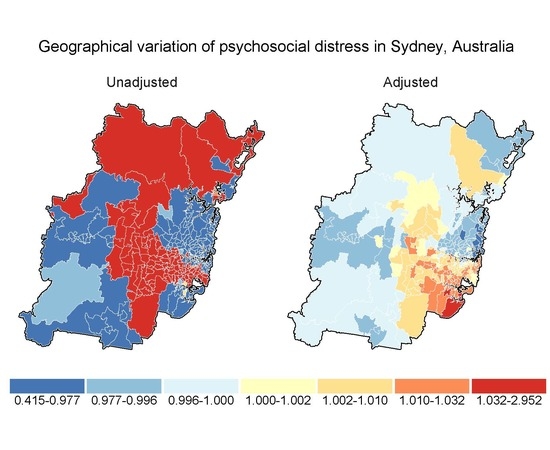

3.3. Spatial Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vigo, D.; Thornicroft, G.; Atun, R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, S.I.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1260–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Genva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, T.; Johnston, A.; Teesson, M.; Whiteford, H.; Burgess, P.; Pirkis, J.; Saw, S. The Mental Health of Australians 2: Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing; Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra, Australia, 2009.

- World Health Assembly. Global Burden of Mental Disorders and the Need for a Comprehensive, Coordinated Response From Health and Social Sectors at the Country Level: Report by the Secretariat (A65/10 Item 13.2). Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/78898 (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switxerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, E.; Coffee, N.; Frank, L.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A.; Hugo, G. Walkability of local communities: Using geographic information systems to objectively assess relevant environmental attributes. Health Place 2007, 13, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, R.; Cohen, D.A. Suburban sprawl and physical and mental health. Public Health 2004, 118, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarloos, D.; Alfonso, H.; Giles-Corti, B.; Middleton, N.; Almeida, O.P. The built environment and depression in later life: The health in men study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, C.; Gallacher, J.; Webster, C. Urban built environment configuration and psychological distress in older men: Results from the Caerphilly study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- James, P.; Hart, J.E.; Banay, R.F.; Laden, F.; Signorello, L.B. Built Environment and Depression in Low-Income African Americans and Whites. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berke, E.M.; Gottlieb, L.M.; Moudon, A.V.; Larson, E.B. Protective association between neighborhood walkability and depression in older men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. 2008. Available online: http://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/ (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Josefsson, T.; Lindwall, M.; Archer, T. Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebar, A.L.; Stanton, R.; Geard, D.; Short, C.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyden, K.M. Social capital and the built environment: The importance of walkable neighborhoods. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porta, M.; Greenland, S.; Hernán, M.; dos Santos Silva, I.; Last, J.M. A Dictionary of Epidemiology, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Palmer, S.; Gallacher, J.; Marsden, T.; Fone, D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehsan, A.M.; De Silva, M.J. Social capital and common mental disorder: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2015, 69, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelens, B.E.; Handy, S.L. Built environment correlates of walking: A review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, S550–S566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Leary, L.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Hess, P.M. The development of a walkability index: Application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayne, D.; Morgan, G.; Willmore, A.; Rose, N.; Jalaludin, B.; Bambrick, H.; Bauman, A. An objective index of walkability for research and planning in the Sydney metropolitan region of New South Wales, Australia: An ecological study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2013, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, C.P.; Andalib, M.; Dunton, G.F.; Wolch, J.; Pentz, M.A. A systematic review of built environment factors related to physical activity and obesity risk: Implications for smart growth urban planning. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e173–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.C.; Sallis, J.F.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Chapman, J.E.; Ahn, D.K.; Kerr, J. Aging in neighborhoods differing in walkability and income: Associations with physical activity and obesity in older adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Floyd, M.F.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Saelens, B.E. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knuiman, M.W.; Christian, H.E.; Divitini, M.L.; Foster, S.A.; Bull, F.C.; Badland, H.M.; Giles-Corti, B. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Influence of the Neighborhood Built Environment on Walking for TransportationThe RESIDE Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Rutter, H.; Compernolle, S.; Glonti, K.; Oppert, J.M.; Charreire, H.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Brug, J.; Nijpels, G.; Lakerveld, J. Obesogenic environments: A systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Dyck, D.; Cerin, E.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Hinckson, E.; Reis, R.S.; Davey, R.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Mitas, J.; Troelsen, J.; MacFarlane, D.; et al. International study of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with body mass index and obesity: IPEN adult study. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2015, 39, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayne, D.J.; Morgan, G.G.; Jalaludin, B.B.; Bauman, A.E. The contribution of area-level walkability to geographic variation in physical activity: A spatial analysis of 95,837 participants from the 45 and Up Study living in Sydney, Australia. Popul. Health Metr. 2017, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merom, D.; Ding, D.; Corpuz, G.; Bauman, A. Walking in Sydney: Trends in prevalence by geographic areas using information from transport and health surveillance systems. J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Du, J.; Inoue, Y. Rate of Physical Activity and Community Health: Evidence from U.S. Counties. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohrenwend, B.P.; Shrout, P.E.; Egri, G.; Mendelsohn, F.S. Nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology: Measures for use in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1980, 37, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drapeau, A.; Marchand, A.; Beaulieu-Prèvost, D. Epidemiology of psychological distress. In Mental Illnesses—Understanding, Prediction and Control; Book Section 5; L’Abate, L., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2012; pp. 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/australianhealthsurvey (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Pattenden, S.; Casson, K.; Cook, S.; Dolk, H. Geographical variation in infant mortality, stillbirth and low birth weight in Northern Ireland, 1992–2002. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, A.; Mayne, D.J.; Jones, B.D.; Bott, L.; Andersen, S.E.; Caputi, P.; Weston, K.M.; Iverson, D.C. Area-Level Socioeconomic Gradients in Overweight and Obesity in a Community-Derived Cohort of Health Service Users—A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, L.; Abellan, J.J.; Hodgson, S.; Jarup, L. Methodologic issues and approaches to spatial epidemiology. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaix, B.; Leyland, A.H.; Sabel, C.E.; Chauvin, P.; Råstam, L.; Kristersson, H.; Merlo, J. Spatial clustering of mental disorders and associated characteristics of the neighbourhood context in Malmö, Sweden, in 2001. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, Y.T.D.; Spittal, M.J.; Pirkis, J.; Yip, P.S.F. Spatial analysis of suicide mortality in Australia: Investigation of metropolitan-rural-remote differentials of suicide risk across states/territories. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamini Ngui, A.; Apparicio, P.; Moltchanova, E.; Vasiliadis, H.M. Spatial analysis of suicide mortality in Québec: Spatial clustering and area factor correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruebner, O.; Lowe, S.R.; Sampson, L.; Galea, S. The geography of post-disaster mental health: Spatial patterning of psychological vulnerability and resilience factors in New York City after Hurricane Sandy. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2015, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Geography: Volume 1—Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC), July 2006 (Catalogue No. 1216.0); Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. TableBuilder Basic. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/tablebuilder (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Geography: Volume 2—Census Geographic Areas, 2006 (Catalogue No. 2905.0); Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2006.

- James, P.; Berrigan, D.; Hart, J.E.; Aaron Hipp, J.; Hoehner, C.M.; Kerr, J.; Major, J.M.; Oka, M.; Laden, F. Effects of buffer size and shape on associations between the built environment and energy balance. Health Place 2014, 27, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, K.; Knuiman, M.; Nathan, A.; Giles-Corti, B.; Christian, H.; Foster, S.; Bull, F. The impact of neighborhood walkability on walking: Does it differ across adult life stage and does neighborhood buffer size matter? Health Place 2014, 25, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- 45 and Up Study Collaborators. Cohort profile: The 45 and Up Study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 37, 941–947. [Google Scholar]

- 45 and Up Study. Researcher Toolkit. Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/for-researchers/ (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- The 45 and Up Study. The 45 and Up Study Data Book—December 2011 Release. Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/data-book/ (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- The 45 and Up Study. The 45 and Up Study Data Book—April 2010 Release. Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/our-work/45-up-study/data-book/ (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA)—Technical Paper, 2006; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.T.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Use of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in ABS Health Surveys, Australia, 2007–08 (Catalgue No. 4817.0.55.001). Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4817.0.55.001 (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Andrews, G.; Slade, T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. New South Wales Adult Population Health Survey. Available online: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/surveys/adult/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2007.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2011–13 (CATALOGUE NO. 4363.0.55.001). Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/4363.0.55.001 (accessed on 31 January 2018).

- Wooden, M. Use of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale in the HILDA Survey; HILDA Project Discussion Paper Series No. 209; Melbourne Institute of Applied and Social Research, The University of Melbourne: Parkville, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, J.; Naismith, S.L.; Luscombe, G.M.; Hickie, I.B. Psychological distress and quality of life in older persons: Relative contributions of fixed and modifiable risk factors. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, E.; Byles, J.E.; Gibson, R.E.; Rodgers, B.; Latz, I.K.; Robinson, I.A.; Williamson, A.B.; Jorm, L.R. Is psychological distress in people living with cancer related to the fact of diagnosis, current treatment or level of disability? Findings from a large Australian study. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 193, S62–S67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banks, E.; Brown, A.; Attia, J.; Joshy, G.; Korda, R.; Reddy, P.; Paige, E. O168 Prospective investigation of psychological distress and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalisation and all-cause mortality, accounting for baseline physical impairment in 203,500 participants in the 45 and Up Study. Glob. Heart 2014, 9, e47–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byles, J.E.; Gallienne, L.; Blyth, F.M.; Banks, E. Relationship of age and gender to the prevalence and correlates of psychological distress in later life. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byles, J.E.; Robinson, I.; Banks, E.; Gibson, R.; Leigh, L.; Rodgers, B.; Curryer, C.; Jorm, L. Psychological distress and comorbid physical conditions: Disease or disability? Depress. Anxiety 2014, 31, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Astell-Burt, T.; Kolt, G.S. Do social interactions explain ethnic differences in psychological distress and the protective effect of local ethnic density? A cross-sectional study of 226 487 adults in Australia. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feng, X.; Astell-Burt, T. What types of social interactions reduce the risk of psychological distress? Fixed effects longitudinal analysis of a cohort of 30,271 middle-to-older aged Australians. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 204, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, E.S.; Jorm, L.; Kolt, G.S.; Bambrick, H.; Lujic, S. Physical activity and psychological distress in older men: Findings from the New South Wales 45 and up study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2012, 20, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korda, R.J.; Paige, E.; Yiengprugsawan, V.; Latz, I.; Friel, S. Income-related inequalities in chronic conditions, physical functioning and psychological distress among older people in Australia: Cross-sectional findings from the 45 and up study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, B.J.; Banks, E.; Gubhaju, L.; Williamson, A.; Joshy, G.; Raphael, B.; Eades, S.J. Measuring psychological distress in older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Australians: A comparison of the K-10 and K-5. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2014, 38, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradise, M.B.; Glozier, N.S.; Naismith, S.L.; Davenport, T.A.; Hickie, I.B. Subjective memory complaints, vascular risk factors and psychological distress in the middle-aged: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phongsavan, P.; Grunseit, A.C.; Bauman, A.; Broom, D.; Byles, J.; Clarke, J.; Redman, S.; Nutbeam, D. Age, Gender, Social Contacts, and Psychological Distress. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 921–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotnikoff, R.C.; Costigan, S.A.; Short, C.; Grunseit, A.; James, E.; Johnson, N.; Bauman, A.; D’Este, C.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Rhodes, R.E. Factors Associated with Higher Sitting Time in General, Chronic Disease, and Psychologically-Distressed, Adult Populations: Findings from the 45 & Up Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127689. [Google Scholar]

- Ussher, J.M.; Perz, J.; Kellett, A.; Chambers, S.; Latini, D.; Davis, I.D.; Rose, D.; Dowsett, G.W.; Williams, S. Health-Related Quality of Life, Psychological Distress, and Sexual Changes Following Prostate Cancer: A Comparison of Gay and Bisexual Men With Heterosexual Men. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E., Jr.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, J.E.; Snow, K.K.; Kosinski, M.; Gandek, B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide; The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux, B.G.; Lei, X.; Breslow, N. Estimation of Disease Rates in Small Areas: A new Mixed Model for Spatial Dependence. In Statistical Models in Epidemiology, the Environment, and Clinical Trials; Halloran, M.E., Berry, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, A.C.; Kulldorff, M.; Curriero, F. Geographical clustering of prostate cancer grade and stage at diagnosis, before and after adjustment for risk factors. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2005, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Waldhoer, T.; Wald, M.; Heinzl, H. Analysis of the spatial distribution of infant mortality by cause of death in Austria in 1984 to 2006. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besag, J.; York, J.; Mollié, A. Bayesian image restoration, with two applications in spatial statistics. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 1991, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A.; Browne, W.J.; Vidal Rodeiro, C.L. Disease mapping with WinBUGS and MLwiN; Statistics in Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, L.; Carlin, B. Disease mapping. In Handbook of Spatial Statistics; Chapman & Hall/CRC Handbooks of Modern Statistical Methods; Gelfand, A.E., Diggle, P.J., Feuentes, M., Guttorp, P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn, D.; Jackson, C.; Best, N.; Thomas, A.; Spiegelhalter, D. The BUGS Book: A Practical Introduction to Bayesian Analysis; Texts in Statistical Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A.; Rubin, D.B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 1992, 7, 457–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowles, M.K.; Carlin, B.P. Markov Chain Monte Carlo Convergence Diagnostics: A Comparative Review. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1996, 91, 883–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealing, N.M.; Banks, E.; Jorm, L.R.; Steel, D.G.; Clements, M.S.; Rogers, K.D. Investigation of relative risk estimates from studies of the same population with contrasting response rates and designs. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegelhalter, D.J.; Best, N.G.; Carlin, B.P.; Van Der Linde, A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2002, 64, 583–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramb, S.M.; Mengersen, K.L.; Baade, P.D. Developing the atlas of cancer in Queensland: Methodological issues. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holowaty, E.J.; Norwood, T.A.; Wanigaratne, S.; Abellan, J.J.; Beale, L. Feasibility and utility of mapping disease risk at the neighbourhood level within a Canadian public health unit: An ecological study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How Big is a Big Odds Ratio? Interpreting the Magnitudes of Odds Ratios in Epidemiological Studies. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Bauman, A.; Pratt, M. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 15, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment: A synthesis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2001, 1780, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N. Environmental and policy measurement in physical research. In Physical Activity Assessments for Health-Related Research; Welk, G., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002; pp. 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- Badland, H.; Schofield, G. Transport, urban design, and physical activity: An evidence-based update. Transp. Res. Transp. Environ. 2005, 10, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Macaulay, G.; Middleton, N.; Boruff, B.; Bull, F.; Butterworth, I.; Badland, H.; Mavoa, S.; Roberts, R.; Christian, H. Developing a research and practice tool to measure walkability: A demonstration project. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2014, 25, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, M.W. Special problems of sociological analysis. In Sociological Research: A Case Approach; Riley, M.W., Merton, R.K., Eds.; Harcourt, Brace, and World: New York, NY, USA, 1963; Volume 1, pp. 700–725. [Google Scholar]

- Alker, H.A. A typology of ecological fallacies. In Quantitative Ecological Analysis; Dogan, M., Ed.; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1969; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.; Gebel, K. Built environment, physical activity, and obesity: What have we learned from reviewing the literature? Health Place 2012, 18, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockton, J.C.; Duke-Williams, O.; Stamatakis, E.; Mindell, J.S.; Brunner, E.J.; Shelton, N.J. Development of a novel walkability index for London, United Kingdom: cross-sectional application to the Whitehall II Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorant, V.; Deliège, D.; Eaton, W.; Robert, A.; Philippot, P.; Ansseau, M. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 157, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntaner, C.; Eaton, W.W.; Miech, R.; O’Campo, P. Socioeconomic Position and Major Mental Disorders. Epidemiol. Rev. 2004, 26, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, K.E.; Wilkinson, R.G. Inequality: An underacknowledged source of mental illness and distress. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campion, J.; Bhugra, D.; Bailey, S.; Marmot, M. Inequality and mental disorders: Opportunities for action. Lancet 2013, 382, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.; Loureiro, A.; Cardoso, G. Social determinants of mental health: A review of the evidence. Eur. J. Psychiatry 2016, 30, 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, D.; Zitko, P.; Jones, K.; Lynch, J.; Araya, R. Country- and individual-level socioeconomic determinants of depression: Multilevel cross-national comparison. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.W.; Park, J.H. Individual and Socioeconomic Contextual Effects on Depressive Symptom in Korea: Multilevel Analysis of Cross-sectional Nationwide Survey. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, J.M.; Ayton, D.R.; Densley, K.; Pallant, J.F.; Chondros, P.; Herrman, H.E.; Dowrick, C.F. The association between chronic illness, multimorbidity and depressive symptoms in an Australian primary care cohort. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, M.; Bravo, G.; Hudon, C.; Lapointe, L.; Dubois, M.F.; Almirall, J. Psychological Distress and Multimorbidity in Primary Care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2006, 4, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ormel, J.; Rijsdijk, F.V.; Sullivan, M.; van Sonderen, E.; Kempen, G.I.J.M. Temporal and Reciprocal Relationship Between IADL/ADL Disability and Depressive Symptoms in Late Life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2002, 57, P338–P347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazemore, A.; Phillips, R.L.; Miyoshi, T. Harnessing Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to Enable Community-Oriented Primary Care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2010, 23, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criqui, M.H. Response bias and risk ratios in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1979, 109, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohr, E.A.; Frydenberg, M.; Henriksen, T.B.; Olsen, J. Does low participation in cohort studies induce bias? Epidemiology 2006, 17, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayne, D.J.; Morgan, G.G.; Jalaludin, B.B.; Bauman, A.E. Is it worth the weight? Adjusting physical activity ratio estimates for individual-level non-response is not required in area-level spatial analyses of the 45 and Up Study cohort. Presented at the 45 and Up Study Annual Forum, Sydney, Australia, 24 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: The potential misuse of a concept and the consequences. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, I.H.; Leyland, A.H.; Rasbash, J.; Goldstein, H. Multilevel Modelling of the Geographical Distributions of Diseases. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 1999, 48, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, D.G. Statistics in medical journals: Some recent trends. Stat. Med. 2000, 19, 3275–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristman, V.; Manno, M.; Côté, P. Loss to Follow-Up in Cohort Studies: How Much is Too Much? Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 19, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Krull, J.L.; Lockwood, C.M. Equivalence of the Mediation, Confounding and Suppression Effect. Prev. Sci. 2000, 1, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huque, M.H.; Anderson, C.; Walton, R.; Ryan, L. Individual level covariate adjusted conditional autoregressive (indiCAR) model for disease mapping. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2016, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rue, H.; Martino, S.; Chopin, N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2009, 71, 319–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivand, R.; Gómez-Rubio, V.; Rue, H. Spatial Data Analysis with R-INLA with Some Extensions. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 63, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Openshaw, S. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem; (CATMOG 38); Geo Books: Norwich, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Characteristics | Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | |

| POSTAL AREA LEVEL | ||||

| Walkability | ||||

| Low | 25,217 | 27.7 | 1983 | 7.9 |

| Low-medium | 31,023 | 34.0 | 2440 | 7.9 |

| Medium-high | 19,232 | 21.1 | 1548 | 8.0 |

| High | 15,670 | 17.2 | 1154 | 7.4 |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | ||||

| Q1—Most | 17,153 | 18.8 | 2096 | 12.2 |

| Q2 | 19,272 | 21.1 | 1800 | 9.3 |

| Q3—Middling | 14,833 | 16.3 | 1109 | 7.5 |

| Q4 | 19,789 | 21.7 | 1177 | 5.9 |

| Q5—Least | 20,095 | 22.0 | 943 | 4.7 |

| INDIVIDUAL LEVEL | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 44,220 | 48.5 | 3008 | 6.8 |

| Female | 46,922 | 51.5 | 4117 | 8.8 |

| Age | ||||

| 45–49 | 13,480 | 14.8 | 1328 | 9.9 |

| 50–54 | 16,619 | 18.2 | 1587 | 9.5 |

| 55–59 | 16,601 | 18.2 | 1367 | 8.2 |

| 60–64 | 13,611 | 14.9 | 938 | 6.9 |

| 65–69 | 10,093 | 11.1 | 536 | 5.3 |

| 70–74 | 6792 | 7.5 | 361 | 5.3 |

| 75–79 | 4898 | 5.4 | 319 | 6.5 |

| 80–84 | 6432 | 7.1 | 435 | 6.8 |

| 85+ | 2616 | 2.9 | 254 | 9.7 |

| Language spoken at home | ||||

| English | 77,307 | 84.8 | 5230 | 6.8 |

| Other | 13,835 | 15.2 | 1895 | 13.7 |

| Education level | ||||

| Less than secondary school | 7236 | 7.9 | 1176 | 16.3 |

| Secondary school graduation | 26,355 | 28.9 | 2267 | 8.6 |

| Trade, certificate or diploma | 28,678 | 31.5 | 2044 | 7.1 |

| University degree | 28,873 | 31.7 | 1638 | 5.7 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Partner | 68,138 | 74.8 | 4457 | 6.5 |

| No partner | 23,004 | 25.2 | 2668 | 11.6 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time work | 32,578 | 35.7 | 2052 | 6.3 |

| Part-time work | 13,122 | 14.4 | 996 | 7.6 |

| Other work | 1319 | 1.4 | 168 | 12.7 |

| Not working | 44,123 | 48.4 | 3909 | 8.9 |

| Health insurance type | ||||

| Private with extras | 53,835 | 59.1 | 3054 | 5.7 |

| Private without extras | 12,822 | 14.1 | 746 | 5.8 |

| Government health care card | 11,656 | 12.8 | 1974 | 16.9 |

| None | 12,829 | 14.1 | 1351 | 10.5 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoked | 53,560 | 58.8 | 3662 | 6.8 |

| Past smoker | 31,276 | 34.3 | 2366 | 7.6 |

| Current smoker | 6306 | 6.9 | 1097 | 17.4 |

| Body mass category | ||||

| Underweight | 1247 | 1.4 | 177 | 14.2 |

| Normal weight | 35,709 | 39.2 | 2467 | 6.9 |

| Overweight | 35,555 | 39.0 | 2458 | 6.9 |

| Obese | 18,631 | 20.4 | 2023 | 10.9 |

| Total physical activity | ||||

| 0 min | 5296 | 5.8 | 912 | 17.2 |

| 1–149 min | 15,102 | 16.6 | 1635 | 10.8 |

| 150–299 min | 15,675 | 17.2 | 1185 | 7.6 |

| ≥300 min | 55,069 | 60.4 | 3393 | 6.2 |

| Diagnosed chronic conditions | ||||

| 0 | 31,050 | 34.1 | 1397 | 4.5 |

| 1 | 36,544 | 40.1 | 2487 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 17,915 | 19.7 | 2049 | 11.4 |

| 3 or more | 5633 | 6.2 | 1192 | 21.2 |

| Treated chronic conditions | ||||

| 0 | 41,261 | 45.3 | 2683 | 6.5 |

| 1 | 29,791 | 32.7 | 2217 | 7.4 |

| 2 | 14,285 | 15.7 | 1363 | 9.5 |

| 3 or more | 5805 | 6.4 | 862 | 14.8 |

| Limited physical functioning | ||||

| None | 32,198 | 35.3 | 1353 | 4.2 |

| Minor | 24,974 | 27.4 | 1169 | 4.7 |

| Moderate | 20,074 | 22.0 | 1798 | 9.0 |

| Severe | 13,896 | 15.2 | 2805 | 20.2 |

| Individual-Level Adjustment | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Prevalence ratios (95% CrI) | |||||

| Constant | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) |

| Walkability | |||||

| Low | – | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 |

| Low-medium | – | – | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | – | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) |

| Medium-high | – | – | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | – | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) |

| High | – | – | 1.03 (0.93–1.15) | – | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | |||||

| Q1—Most | – | – | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Q2 | – | – | – | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) |

| Q3— Middling | – | – | – | 0.92 (0.86–1.00) | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) |

| Q4 | – | – | – | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 0.90 (0.83–0.97) |

| Q5—Least | – | – | – | 0.82 (0.76–0.90) | 0.83 (0.76–0.90) |

| Model diagnostics | |||||

| pD | 127.85 | 21.73 | 24.40 | 15.32 | 17.20 |

| DIC | 1557.25 | 1418.33 | 1419.26 | 1409.06 | 1410.40 |

| Spatial fraction | 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.2434 | ||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.32 | 1.25–1.38 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.02 |

| Age | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| 45–49 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 50–54 | 0.97 | 0.89–1.04 | 0.82 | 0.76–0.89 |

| 55–59 | 0.82 | 0.76–0.89 | 0.57 | 0.52–0.62 |

| 60–64 | 0.68 | 0.62–0.74 | 0.36 | 0.32–0.39 |

| 65–69 | 0.51 | 0.46–0.57 | 0.21 | 0.18–0.24 |

| 70–74 | 0.51 | 0.46–0.58 | 0.16 | 0.14–0.18 |

| 75–79 | 0.64 | 0.56–0.72 | 0.16 | 0.14–0.19 |

| 80–84 | 0.66 | 0.59–0.74 | 0.13 | 0.12–0.15 |

| 85+ | 0.98 | 0.85–1.13 | 0.14 | 0.12–0.17 |

| Language spoken at home | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| English | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Other | 2.19 | 2.07–2.31 | 1.92 | 1.80–2.04 |

| Education level | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Less than secondary school | 3.23 | 2.98–3.50 | 1.70 | 1.55–1.87 |

| Secondary school graduation | 1.56 | 1.47–1.67 | 1.20 | 1.12–1.29 |

| Trade, certificate or diploma | 1.28 | 1.19–1.36 | 1.09 | 1.02–1.18 |

| University degree | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Relationship status | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Partner | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| No partner | 1.87 | 1.78–1.97 | 1.41 | 1.33–1.50 |

| Employment status | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Full-time work | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Part-time work | 1.22 | 1.13–1.32 | 1.14 | 1.05–1.24 |

| Other work | 2.17 | 1.84–2.57 | 1.57 | 1.30–1.89 |

| Not working | 1.45 | 1.37–1.53 | 1.46 | 1.35–1.58 |

| Health insurance type | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Private with extras | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Private without extras | 1.03 | 0.95–1.12 | 1.03 | 0.94–1.12 |

| Government health care card | 3.39 | 3.19–3.60 | 1.78 | 1.65–1.92 |

| None | 1.96 | 1.83–2.09 | 1.36 | 1.27–1.47 |

| Smoking status | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Never smoked | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Past smoker | 1.12 | 1.06–1.18 | 1.07 | 1.00–1.13 |

| Current smoker | 2.87 | 2.67–3.09 | 1.64 | 1.51–1.78 |

| Body mass category | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| Underweight | 2.23 | 1.89–2.63 | 1.61 | 1.34–1.93 |

| Normal weight | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Overweight | 1.00 | 0.94–1.06 | 0.93 | 0.87–0.99 |

| Obese | 1.64 | 1.54–1.75 | 0.88 | 0.82–0.94 |

| Total physical activity | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| 0 min | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–149 min | 0.58 | 0.53–0.64 | 0.75 | 0.68–0.82 |

| 150–299 min | 0.39 | 0.36–0.43 | 0.64 | 0.58–0.71 |

| ≥300 min | 0.32 | 0.29–0.34 | 0.58 | 0.53–0.64 |

| Diagnosed chronic conditions | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.55 | 1.45–1.66 | 1.56 | 1.45–1.68 |

| 2 | 2.74 | 2.55–2.94 | 2.45 | 2.26–2.66 |

| 3 or more | 5.70 | 5.24–6.19 | 4.32 | 3.90–4.78 |

| Treated chronic conditions | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0240 | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.16 | 1.09–1.23 | 1.02 | 0.96–1.10 |

| 2 | 1.52 | 1.42–1.62 | 1.01 | 0.93–1.10 |

| 3 or more | 2.51 | 2.31–2.72 | 1.17 | 1.05–1.29 |

| Limited physical functioning | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | ||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Minor | 1.12 | 1.03–1.21 | 1.24 | 1.15–1.35 |

| Moderate | 2.24 | 2.09–2.41 | 2.15 | 1.98–2.33 |

| Severe | 5.77 | 5.38–6.17 | 4.41 | 4.05–4.79 |

| Baseline | Walkability | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence ratios (95% CrI) | ||

| Constant | 0.97 (0.97–1.02) | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) |

| Walkability | ||

| Low | – | 1.00 |

| Low-medium | – | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) |

| Medium-high | – | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) |

| High | – | 1.03 (0.93–1.15) |

| Model diagnostics | ||

| pD | 23.58 | 25.97 |

| DIC | 1420.05 | 1420.99 |

| Spatial fraction | 0.90 | 0.90 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mayne, D.J.; Morgan, G.G.; Jalaludin, B.B.; Bauman, A.E. Does Walkability Contribute to Geographic Variation in Psychosocial Distress? A Spatial Analysis of 91,142 Members of the 45 and Up Study in Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020275

Mayne DJ, Morgan GG, Jalaludin BB, Bauman AE. Does Walkability Contribute to Geographic Variation in Psychosocial Distress? A Spatial Analysis of 91,142 Members of the 45 and Up Study in Sydney, Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(2):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020275

Chicago/Turabian StyleMayne, Darren J., Geoffrey G. Morgan, Bin B. Jalaludin, and Adrian E. Bauman. 2018. "Does Walkability Contribute to Geographic Variation in Psychosocial Distress? A Spatial Analysis of 91,142 Members of the 45 and Up Study in Sydney, Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 2: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020275

APA StyleMayne, D. J., Morgan, G. G., Jalaludin, B. B., & Bauman, A. E. (2018). Does Walkability Contribute to Geographic Variation in Psychosocial Distress? A Spatial Analysis of 91,142 Members of the 45 and Up Study in Sydney, Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020275