1. Introduction

There is evidence that the structure of networks at the workplace can have an impact on work performance [

1]. This may be through engagements within the group where individual members can use the knowledge of other members of the group (intra-group relations) [

2], but can also improve performance through accessing actors, skills and knowledge external to the organization. Previous studies have indicated that innovative ideas emerge from the intersection of social worlds [

3], that group effectiveness is related to close relationships and bridging relationships [

4] and is also relevant for collaboration among groups of individuals in health policy processes [

5]. In this sense, it has been demonstrated that the frequency of exchanges of relational resources is positively associated with satisfaction, emotions and relational cohesion [

6]. Additionally, collaborative work could start from the workplace when employees contact local authorities, charities, private business and key public personnel, among others [

5], exchanging experiences, knowledge and creating emerging ties to increase their social capital by bridging from one group to another [

7], all of them important in the policy-making processes [

8].

In the context of healthcare, there is evidence that relationships between healthcare professionals might be optimized through access to advice or help at work, by enhancing collective efficacy [

9] and by building positive relations between different groups, organisational units and hierarchical levels [

10,

11,

12]. For example, Mehra et al. [

13] showed that the embeddedness of leaders in the friendship network of their subordinates and supervisors had implications for group performance and leader reputation. Furthermore, healthcare professionals build friendship networks with employees of the same role, creating a platform for the effective spread of information when there is an absence of clinical leaders [

14]. This might be through the engagement of employees [

15], developing effective relationships over formal hierarchical positions [

5] and building a collaborative organizational culture [

16]. Network analysis seems appropriate in the context of health policies, as it offers possibilities to represent network processes and explore the bridging role played by opinion leaders and other actors in the network [

17]. This perspective, through the social network analysis method, could facilitate systemic thinking capable of addressing the challenges and uncertainty related to a sustainable model of medical care. The analysis of structural patterns and associated factors can provide a set of indicators that are not available to other methodologies [

18].

However, barriers between professional groups tend to inhibit inter-professional interaction partners [

19], displaying different structural configurations and, therefore, influencing job performance and atmosphere within the team. The importance of ties across hierarchies, with other departments inside organizations or other individuals outside an organization to improve performance, has been reported previously by Krackhardt Stern [

20]. Meltzer et al. [

21] demonstrated that employees in health organizations were connected with other peers to get advice, help in their task or to find some emotional support. Drawing on existing institutional processes, as well as the effective use of new Information and Communication Technology (ICT) can all be mobilized in enhancing effective networks within and across teams and organizations that can be geographically dispersed [

22].

Despite the importance of social network research in organizations [

23], there are few studies looking specifically at the effectiveness of social networks in healthcare settings and their contributions to the quality of patient care [

24]. There is a gap in the literature regarding the relationship between social networks (including ties within and outside healthcare organization) and work performance in healthcare settings. This paper aims to describe professional relationships of healthcare professionals inside and outside their healthcare organization and to explore the types of advice-seeking ties related to job performance. The results obtained can inform the decision making process and support the work of managers of health organizations. The study also aims to contribute to the better understanding of relations between people working within the healthcare system and offer inroads to understanding the processes that can shape performance.

The following sections describe the operationalisation of these objectives, the instruments used and the process for data collection, presentation and interpretation of the results, as well as a summary of the key points.

4. Discussion

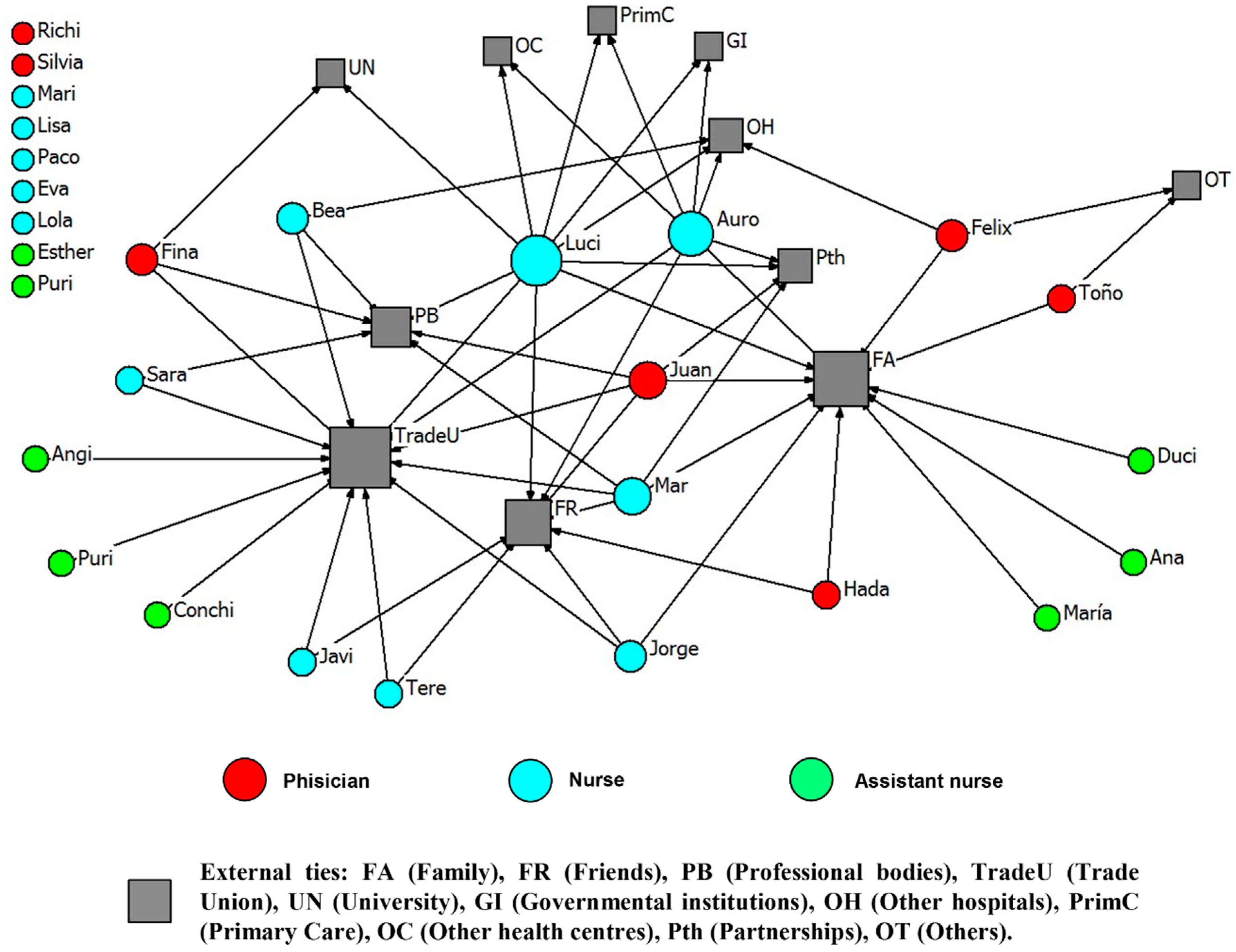

The aim of our study was to describe professional relationships of healthcare workers inside and outside their healthcare organisation and to explore the types of advice-seeking ties related to job performance. To address this research gap, a social network approach was used to describe how health employees’ ties build networks to transfer resources such as giving advice outside the organisation. Job performance was evaluated at the individual, supervisor and senior manager levels in order to investigate and compare social networks and group dependences on individual responses [

32].

Our findings indicate that there is a link between having external contacts outside the healthcare workplace and job performance. However, there were differences between physicians and nurses. Thus, at the individual and team level, external ties to improve the workplace and job performance evaluated by senior managers were positively correlated, but only for physicians. Similar findings have been reported previously suggesting that physicians’ network density and external ties can enhance performance and “allow contact with fresh, not redundant knowledge” [

33]. The explanation that physicians have more external ties might be related to seeking advice, as doctors are more focused on the decision-making process about therapeutic plans. This suggestion is in line with Chung and Jackson [

34], who stated that “effective performance of knowledge intensive teams depends on free-flowing questioning, advice giving, and knowledge used among team members and across team boundaries”. The absence of statistically-significant associations between nurses’ ties and job performance might be related to role, competences and expectations from the nursing role associated with the need to develop very close relationships with team members in providing answers and developing solutions in a short period of time. This fact implies a high level of inter-personal trust in dealing with emotional stress and, thus, the need to create strong networks of people with similar experiences inside the workplace [

35]. Additionally, our findings suggest that senior managers were more aware of the external connections that physicians have, in comparison to those of nurses. This might be related to homophily (the tendency of people to interact more with their own kind [

2]) along gender and occupation lines (i.e., the majority of senior managers are male and physicians). Professional groups, within healthcare organisations, might also have a low level of interactions in the workplace as a consequence of conflicts. For example, communication between nurses and physicians is complex and even difficult to track sometimes, and there is a lack of communication, which has a potentially negative impact on outcomes [

36]. Some researchers have highlighted that gaps between nurses and doctors can inhibit the development of inter-professional networks [

33,

37].

However, there is evidence that external connections develop knowledge translation, which is potentially relevant to innovation in health contexts [

38], and they are therefore potentially beneficial for both physicians and nurses. Therefore, different ways to access a wider network and outside contacts should be considered in relation to professional development [

35]. In this sense, the use of social network analysis might allow us to “dive” into these social structures of teams within organizations and potentially lead to the development of innovative interventions. For example, we suggest that in order to improve performance, senior managers and supervisors might have a key role to play by encouraging healthcare professionals to share information with individuals and teams within and across organisations and also by developing an understanding of the roles different employees play within the existing team configurations. Furthermore, the engagement of nurses in research and innovative practices might allow them to negotiate and navigate different networks in order to find new resources [

39]. White et al. [

40] found that in a routine context, the formal leader can encourage generalised exchange, which brings indirect reciprocity. In this sense, managers could draw on interventions that allow the identification, lining up with and development of shared strategies with key external actors. For example, the “Net-Map” technique might be applied to map all the contacts in different circles, identifying who are the closest contacts. This combines participatory diagnosis and strategic planning with the intervention of actors involved in an important public health or community development issue [

41].

Finally, to include innovation in healthcare settings, it might be useful to consider external ties as a source of knowledge transfer. In this sense, the use of social network analysis might be relevant for identifying and building relationships with external contacts.

Limitations

This study shows an important limitation regarding the number of participants. Furthermore, although these findings report on the interactions of a small group of healthcare providers in a region of Spain and thus may not be reproduced in other populations, they provide a starting point to consider the potential role of social networks in improving job performance in healthcare organizations. Finally, the respondents might have been concerned about confidentiality with possible impact on the truthfulness of their responses about seeking advice.