Improving Sexual Health Education Programs for Adolescent Students through Game-Based Learning and Gamification

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Serious Games as a New Pedagogy

1.2. Game-Based Learning

1.3. Gamification

1.4. Theoretical Framework

1.5. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

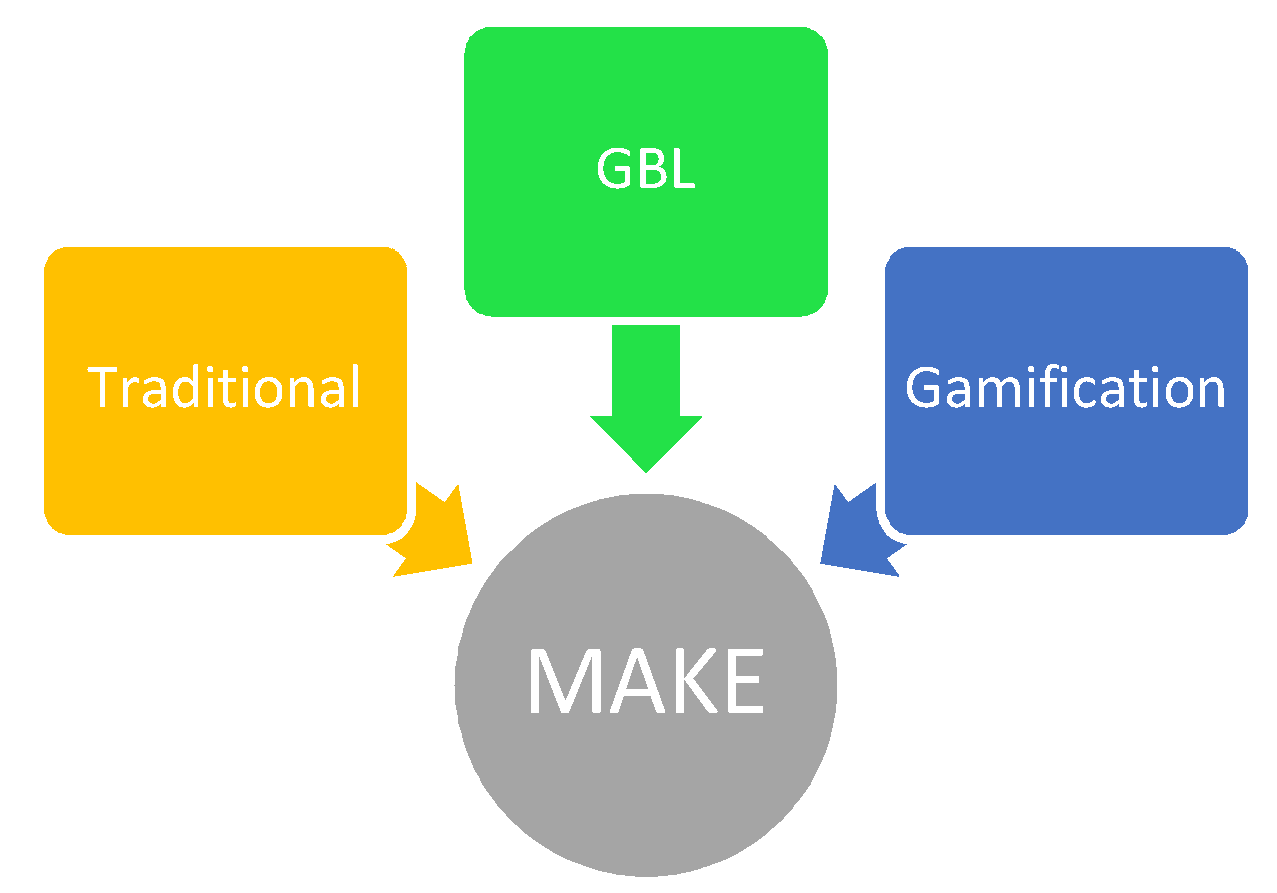

2.3. Teaching Methods (Procedure)

2.3.1. Traditional Teaching

2.3.2. Game-Based Learning

2.3.3. Gamification

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Adolescent Sexual Health Literacy Tests

2.4.2. Evaluation of Teaching Approaches

2.4.3. Focus Group Interview

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Baseline Characteristics

3.2. ASHLT Measures

3.3. Evaluation of Teaching Methods with MAKE

3.3.1. Motivation

3.3.2. Attitude

3.3.3. Knowledge

3.3.4. Engagement

4. Discussion

4.1. ASHLT

4.2. MAKE Framework

4.2.1. Motivation

4.2.2. Attitude

4.2.3. Knowledge

4.2.4. Engagement

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Implications for Research and Practice

4.4.1. For Students

- Adolescents should use the games wisely to obtain the intended knowledge and skills that help them to reduce risky sexual behaviour during and after adolescents.

- Efforts to include the end users (adolescents) in the research and development of sexual education games will enhance the games and provide a user-friendly platform for the target audience.

4.4.2. For Teachers

- Teachers responsible for teaching sexual and reproductive health among adolescents must be adequately acquainted with the subject.

- Teachers should be given support and encouraged to initiate the application of innovative approaches such as digital games in sexual health education.

- Input from teachers when developing, implementing, and investigating the use of sexual education games in the classroom is vital and should be encouraged.

4.4.3. At School Level

- Technology implementation that aligns with current operating systems and frequent upgrades to software and hardware are required.

- Adolescents should be provided with the appropriate sexual and reproductive health information and education to equip them with the knowledge and skills to make informed choices on both social and sexual aspects of life.

- The subject matter needs to be compatible with the school setting, socially acceptable norms, and cultural values, as freely talking about sexuality and sexual behaviour publicly is not acceptable, and the subject can be taboo in certain populations.

4.4.4. For Parents

- Parents should be active participants and engage in the development and implementation of sexual health education games.

- Parents are a vital resource for determining both short- and long-term impacts of health games and should be included in efforts to understand the outcomes of these innovative teaching approaches.

4.4.5. For Policy and Decision-Makers

- Efforts to remodel the current curriculum and apply innovative teaching methods such as sexual health education GBL and Gamification are greatly needed.

- Policy- and decision-makers are advised to emphasize and support the use of games for improving sexual health education without interfering with the traditional values and beliefs of the study community.

- Create open discussions and provide support for research-based evidence to ensure best practice models to teach sexual health education are developed.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. MAKE Evaluation

Survey Questionnaire

| Measure | SD | D | N | A | SA |

| MOTIVATION: Attention Statement | |||||

| There was something interesting at the beginning of the instructional method that got my attention. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching approach used is eye catching. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The quality of activity in the teaching method holds my attention. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The design of the teaching method looks appealing. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| MOTIVATION: Relevance Statement | |||||

| I could relate the content taught through this method to things I have thought about in my own future life. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The content taught through this approach will be useful during my adolescent period. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The content and instructional style convey the impression that the course is worth knowing. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The content in the teaching approach will be useful to me. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| MOTIVATION: Confidence Statement | |||||

| I could really understand quite easily of the material taught through this teaching method. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The exercises in this teaching approach were too easy. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The good organization of the content helped me be confident that I would learn better in this approach. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching approach was simpler to understand than I would like for it to be. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| MOTIVATION: Satisfaction Statement | |||||

| I really enjoyed learning with this teaching method. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| It was a pleasure to learn sexual health behaviors through this pedagogy. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Completing the exercise in this teaching method gave me a satisfying feeling of accomplishment. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I learned somethings that were surprising or unexpected with this teaching method. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| ATTITUDE: Affective Attitude Statement | |||||

| The instructional approach increases my participation in the sexual health education. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I feel happy to be taught sexual health education through this teaching method. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching method used makes sexual health education more interesting. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching method I attended is appropriate for the delivery of sexual health skills. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching method used is an ideal for sexual health education. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| ATTITUDE: Cognitive Attitude Statement | |||||

| The teaching method I attended enhanced my understanding of sexual health behaviour issues. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The instructional approach explained the sexual health learning materials very well. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I found the instructional worthwhile in the sexual health course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The method of instruction used in the sexual health course I attended was interesting. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching method used arouses interest in sexual health education program. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| KNOWLEDGE: Importance of Knowledge Statement | |||||

| The teaching approach enhanced my knowledge about STDs, STIs, and HIV/AIDS. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I gained knowledge about reproductive health through this teaching method. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I gained knowledge about sexual decision-making through the method of instruction. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The instructional method used helped me gain knowledge about good manners and personal hygiene. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| KNOWLEDGE: Application of Knowledge Statement | |||||

| I will apply the sexual coercion and assault knowledge taught through this approach. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The topic of responsible sexual behavioral practices taught in this approach seems very relevant. | |||||

| The method of teaching helped me gain knowledge on dealing with peer pressure during adolescence. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| KNOWLEDGE: Effectiveness of Knowledge Statement | |||||

| The method of instruction used is very active as it helped my understanding of the importance of abstinence. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching approach is very effective as it extended my existing understanding of the course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| This teaching method is very effective in imparting knowledge in sexual health education programs. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| ENGAGEMENT: Emotional Engagement Statement | |||||

| The teaching method I attended it was very easy to understand the learning contents. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I have been effective in this course as the method of instruction was engaging. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching method used facilitates my active participation in the subject taught. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The method of instruction used caught my attention during the course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| This method allowed my expression of thoughtful ideas relevant to the course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The instructional approach used during the course made me interested. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| ENGAGEMENT: Cognitive Engagement Statement | |||||

| I demonstrated my interest and enthusiasm as well as use of positive humor during the course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| This teaching method is relevant for engaging students in the sexual education course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| The teaching strategy used enhanced my engagement in the course. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| I focused on the learning activity given in this teaching approach. | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| Notes: SD = Strongly Disagree (1 point); D = Disagree (2 points); N = Neutral (3 points); A = Agree (4 points); and SA = Strongly Agree (5 points). | |||||

Appendix B. MAKE Evaluation

Focus Group Interview Guide

- Do you think the teaching method motivated you to learn? How and why?

- Do you think the teaching method affect your learning attitude? How and why?

- Do you think the teaching method enhanced you to gain the intended knowledge? How and why?

- Do you think the teaching method engaged you during learning? How and why?

References

- Walcott, C.M.; Meyers, A.B.; Landau, S. Adolescent sexual risk behaviors and school-based sexually transmitted infection/HIV prevention. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlyakado, B.P. Attitudes and Views of Teachers towards Students’ Sexual Relationships in Secondary Schools in Tanzania. Acad. Res. Int. 2013, 4, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, G.M.; Farrell, C. Parents, Peers, Perceived Risk of Harm, and the Neighborhood: Contextualizing Key Influences on Adolescent Substance Use. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, M.; Peto, J.; Franceschi, S. Time since first sexual intercourse and the risk of cervical cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 2638–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanato, M.; Saranrittichai, K. Early experience of sexual intercourse—A risk factor for cervical cancer requiring specific intervention for teenagers. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2006, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joy, T.; Sathian, B.; Bhattarai, C.; Chacko, J. Awareness of cervix cancer risk factors in educated youth: A cross-sectional, questionnaire based survey in India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 12, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Louie, K.S.; De Sanjose, S.; Diaz, M.; Castellsagué, X.; Herrero, R.; Meijer, C.J.; Shah, K.; Franceschi, S.; Mũoz, N.; Bosch, F.X. Early age at first sexual intercourse and early pregnancy are risk factors for cervical cancer in developing countries. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Makuza, J.D.; Nsanzimana, S.; Muhimpundu, M.A.; Pace, L.E.; Ntaganira, J.; Riedel, D.J. Prevalence and risk factors for cervical cancer and pre-cancerous lesions in Rwanda. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanwesenbeeck, I.; Westeneng, J.; de Boer, T.; Reinders, J.; van Zorge, R. Lessons learned from a decade implementing Comprehensive Sexuality Education in resource poor settings: The World Starts with Me. Sex Educ. 2016, 16, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Developing Sexual Health Programmes. A Framework for Action; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, A.S.; Abraham, C.; Denford, S.; Ball, S. School-based sexual health education interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullinax, M.; Mathur, S.; Santelli, J. Adolescent Sexual Health and Sexuality Education. In International Handbook on Adolescent Health and Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Haruna, H.; Hu, X.; Chu, S.K.W. Adolescent School-Based Sexual Health Education and Training: A Literature Review on Teaching and Learning Strategies. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2018, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.S.; Abraham, C.; Denford, S.; Mathews, C. Design, implementation and evaluation of school-based sexual health education in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative study of researchers’ perspectives. Sex Educ. 2018, 18, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avert HIV and AIDS in Tanzania: Global Information and Advice on HIV & AIDS. Available online: http://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/tanzania#footnote16_i9h45mp (accessed on 15 September 2016).

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global AIDS Update 2016: Enormous Gains, Persistent Challenges; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, M.; Likindikoki, S.; Kaaya, S. “Bend a Fish When the Fish Is Not Yet Dry”: Adolescent Boys’ Perceptions of Sexual Risk in Tanzania. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mkumbo, K.A. Teachers’ Attitudes towards and Comfort about Teaching School-Based Sexuality Education in Urban and Rural Tanzania. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriou, A.; Bullock, S.; Graham, C.A.; Ingham, R. Using Computer Simulations for Investigating a Sex Education Intervention: An Exploratory Study. JMIR Serious Games 2017, 5, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carswell, K.; Hons, B.A.; Mccarthy, D.O.; Murray, E.; McCarthy, O.; Murray, E.; Bailey, J. V Integrating psychological theory into the design of an online intervention for sexual health: The sexunzipped website. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2012, 1, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.K.W.; Kwan, A.C.M.; Reynolds, R.; Mellecker, R.R.; Tam, F.; Lee, G.; Hong, A.; Leung, C.Y. Promoting Sex Education Among Teenagers Through an Interactive Game: Reasons for Success and Implications. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSmet, A.; Shegog, R.; Van Ryckeghem, D.; Crombez, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Involving Serious Digital Games. Games Health 2015, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz, J.; Santa Maria, D.; Dube, S.; Markham, C.; McLaughlin, J.; Wilkerson, J.M.; Peskin, M.F.; Tortolero, S.; Shegog, R. Promoting Parent–Child Sexual Health Dialogue with an Intergenerational Game: Parent and Youth Perspectives. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGonigal, J. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World; Penguin: London, UK, 2011; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Graafland, M.; Dankbaar, M.; Mert, A.; Lagro, J.; De Wit-Zuurendonk, L.; Schuit, S.; Schaafstal, A.; Schijven, M. How to Systematically Assess Serious Games Applied to Health Care. JMIR Serious Games 2014, 2, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashibuchi, M.; Sakamoto, A. The educational effectiveness of a simulation/game in sex education. Simul. Gaming 2015, 32, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.H.; Wong, C.K.H.; Wong, W.C.W. A peer-led, social media-delivered, safer sex intervention for Chinese college students: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouris, A.; Mancino, J.; Jagoda, P.; Hill, B.J.; Gilliam, M. Reinvigorating adolescent sexuality education through alternate reality games: The case of The Source. Sex Educ. 2016, 16, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnab, S.; Clarke, S. Towards a trans-disciplinary methodology for a game-based intervention development process. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 279–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSmet, A.; Van Ryckenghem, D.; Compernolle, S.; Baranowski, T.; Thompson, D.; Crombez, G.; Poels, K.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Bastiaensens, B.; Van Cleemput, K.; et al. A Meta-Analysis of Serious Digital Games for Healthy Lifestyle Promotion. Prev. Med. 2014, 2, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; McKanna, J.; Calabrese, S.; Seif El-Nasr, M. Iterative Design and Testing for the Development of a Game-Based Chlamydia Awareness Intervention: A Pilot Study. Games Health J. 2017, 6, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noemí, P.-M.; Máximo, S.H. Educational games for learning. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hieftje, K.; Edelman, E.J.; Camenga, D.R.; Fiellin, L.E. Electronic media-based health interventions promoting behavior change in youth: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiellin, L.E.; Hieftje, K.D.; Pendergrass, T.M.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Duncan, L.R.; Dziura, J.D.; Sawyer, B.G.; Mayes, L.; Crusto, C.A.; Forsyth, B.W.C.; et al. Video game intervention for sexual risk reduction in minority adolescents: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hieftje, K.; Fiellin, L.E.; Pendergrass, T.; Duncan, L.R. Development of an HIV Prevention Videogame Intervention: Lessons Learned. Int. J. Serious Games 2016, 3, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, T.; Blumberg, F.; Buday, R.; DeSmet, A.; Fiellin, L.E.; Green, C.S.; Kato, P.M.; Lu, A.S.; Maloney, A.E.; Mellecker, R.; et al. Games for Health for Children—Current Status and Needed Research. Games Health J. 2016, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chib, A. Promoting Sexual Health Education via Gaming: Evidence from the Barrios of Lima, Peru. In Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games: Multidisciplinary Approaches; Felcia, P., Ed.; Information Science Reference: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cates, J.R.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Diehl, S.J.; Stockton, L.L.; Porter, J.; Ihekweazu, C.; Gurbani, A.S.; Coyne-Beasley, T. Developing a Serious Videogame for Preteens to Motivate HPV Vaccination Decision Making: Land Secr. Gardens. Games Health J. 2018, 7, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnab, S.; Brown, K.; Clarke, S.; Dunwell, I.; Lim, T.; Suttie, N.; Louchart, S.; Hendrix, M.; De Freitas, S. The development approach of a pedagogically-driven serious game to support Relationship and Sex Education (RSE) within a classroom setting. Comput. Educ. 2013, 69, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dicheva, D.; Dichev, C.; Agre, G.; Angelova, G. Gamification in Education: A Systematic Mapping Study. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hanus, M.D.; Fox, J. Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.A.; Lumsden, J.; Rivas, C.; Steed, L.; Edwards, L.A.; Thiyagarajan, A.; Sohanpal, R.; Caton, H.; Griffiths, C.J.; Munafò, M.R.; et al. Gamification for health promotion: Systematic review of behaviour change techniques in smartphone apps. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke, K.A. Gamification in Introductory Computer Science. Master’s Thesis, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Landers, R.N.; Landers, A.K. An Empirical Test of the Theory of Gamified Learning: The Effect of Leaderboards on Time-on-Task and Academic Performance. Simul. Gaming 2014, 45, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoech, D.; Boyas, J.F.; Black, B.M.; Elias-Lambert, N. Gamification for Behavior Change: Lessons from Developing a Social, Multiuser, Web-Tablet Based Prevention Game for Youths. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2013, 31, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huhn, K.J.; Tan, A.; Douglas, R.E.; Li, H.G.; Murti, M.; Lee, V. “Testing is healthy” TimePlay campaign: Evaluation of sexual health promotion gamification intervention targeting young adults. Can. J. Public Health 2017, 108, e85–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, W.-M.; Lee, Y.-J. “Vygotsky’s Neglected Legacy”: Cultural-Historical Activity Theory. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 186–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaptelinin, V. Activity Theory. Available online: http://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/activity_theory.html (accessed on 7 September 2016).

- Engeström, Y. Learning by Expanding: An Activity Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research; Orienta-Konsultit: Helsinki, Finland, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, T. Activity-based scenario design, development, and assessment in serious games. In Gaming and Cognition: Theories and Practice from the Learning Sciences; Van Eck, R., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 213–225. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, H.; Gain, J.; Marais, P.; O’Donovan, S. Reimagining Gamification through the Lens of Activity Theory. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 1328–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Flisher, A.J.; Mathews, C.; Mukoma, W.; Jansen, S. HIV education in South African schools: The dilemma and conflicts of educators. Scand. J. Public Health 2009, 37 (Suppl. 2), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bilinga, M.J. Sexuality Education for Prevention of Pregnancy and HIV Infections: How do Tanzanian Primary Teachers Deliver it ? Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. 2016, 26, 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Haruna, H.; Hu, X.; Chu, S.K.W.; Mellecker, R.R. Initial validation of the MAKE framework: A comprehensive instrument for evaluating the efficacy of game-based learning and gamification in adolescent sexual health literacy. Ann. Glob. Health 2018, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hew, K.F.; Huang, B.; Chu, K.W.S.; Chiu, D.K.W. Engaging Asian students through game mechanics: Findings from two experiment studies. Comput. Educ. 2016, 92–93, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.; Doyle, E. Individualising gamification: An investigation of the impact of learning styles and personality traits on the efficacy of gamification using a prediction market. Comput. Educ. 2017, 106, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R.A.; Hueros, A.D. Motivational factors that influence the acceptance of Moodle using TAM. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1632–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bilinga, M.; Mabula, N. Teaching Sexuality Education in Primary Schools in Tanzania: Challenges and Implications. J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, T. Design research from a technology perspective. In Educational Design Research; Van Den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., Nieveen, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Goto, A.; Lai, A.Y.; Kumagai, A.; Koizumi, S.; Yoshida, K.; Yamawaki, K.; Rudd, R.E. Collaborative Processes of Developing a Health Literacy Toolkit: A Case from Fukushima after the Nuclear Accident. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingood, W.C.; Monticalvo, D.; Bernhardt, J.M.; Wells, K.T.; Harris, T.; Kee, K.; Hayes, J.; George, D.; Woodhouse, L.D. Engaging Adolescents through Participatory and Qualitative Research Methods to Develop a Digital Communication Intervention to Reduce Adolescent Obesity. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 44, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unity Technologies Game Engine, Tools and Multiplatform. Available online: https://unity3d.com/es/unity (accessed on 14 November 2016).

- Bowen, E.; Walker, K.; Mawer, M.; Holdsworth, E.; Sorbring, E.; Helsing, B.; Leen, E.; Held, P.; Jans, S. “It’s like you’re actually playing as yourself”: Development and preliminary evaluation of ‘Green Acres High’, a serious game-based primary intervention to combat adolescent dating violence. Psychosoc. Interv. 2014, 23, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbring, E.; Bolin, A.; Ryding, J. Game-Based Intervention—A technical tool for social workers to combat adolescent dating violence. Adv. Soc. Work 2015, 16, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Paperny, D.M.; Starn, J.R. Adolescents pregnancy prevention by health education computer games: Computer-assisted instruction of knowledge and attitude. Pediatrics 1989, 83, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rehm, C.M. Student and Teacher Perceptions of Game Plan: A Middle-Level Sex Education Program. Ph.D. Thesis, Immaculata University, Immaculata, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.E.; Edmundson-Drane, E.; Harris, K. Computer-assisted instruction: An effective instructional method for HIV prevention education. J. Adolesc. Health 2000, 26, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, V.E. Evaluability Assessment of Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention and Sexual Health Program, Be Proud! Be Responsible! In New York State. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Acharya, D.R. Measuring the Effectiveness of Teaching Sex Education in Nepalese Secondary Schools—An Outcome from a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT). Ph.D. Thesis, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.H.; Huang, W.Y.; Tschopp, J. Sustaining iterative game playing processes in DGBL: The relationship between motivational processing and outcome processing. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernersbach, B.M. Healthy Sexuality: Evaluating a Psychoeducational Group Promoting Knowledge, Communication, and Positive Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, T. The Effects of Service-Learning on Student Classroom Engagement: A Mixed-Method Study of the Effects of Service-Learning on Student Engagement in Eighth Grade Science Classrooms. Ph.D. Thesis, Missouri Baptist University, St. Louis, MO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, S.; Schumm, J.S.; Sinagub, J.M. Focus Group Interviews in Education and Psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, A.; Howlett, E.; Brady, D.; Drennan, J. The focus group method: Insights from focus group interviews on sexual health with adolescents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 2588–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heary, C.M.; Hennessy, E. The use of focus group interviews in pediatric health care research. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2002, 27, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Huang, W.; Diefes-Dux, H.; Imbrie, P.K. A preliminary validation of Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Satisfaction model-based Instructional Material Motivational Survey in a computer-based tutorial setting. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2006, 37, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Petty, R.E. The Role of the Affective and Cognitive Bases of Attitudes in Susceptibility to Affectively and Cognitively Based Persuasion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkumbo, K.A.K.; Ingham, R. What Tanzanian parents want (and do not want) covered in school-based sex and relationships education. Sex Educ. 2010, 10, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, T.K.; Malhotra, N.K. Affective and Cognitive Components of Attitudes in High-Stakes Decisions: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Hormone Replacement Therapy Use. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 678–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.M.; Lee, B.; Constance, N.; Hynes, K. Examining Youth and Program Predictors of Engagement in Out-of-School Time Programs. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 1557–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.D. Student Engagement: Teacher Handbook; International Center for Leadership in Education: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarron, E.; Schopf, T.; Serrano, J.A.; Fernandez-Luque, L.; Dorronzoro, E. Gamification strategy on prevention of STDs for youth. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 192, p. 1066. [Google Scholar]

- Bamidis, P.D.; Gabarron, E.; Hors-Fraile, S.; Konstantinidis, E.; Konstantinidis, S.; Rivera, O. Chapter 7—Gamification and Behavioral Change: Techniques for Health Social Media. In Participatory Health Through Social Media; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 112–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhalst, J.; Luyckx, K.; Van Petegem, S.; Soenens, B. The Detrimental Effects of Adolescents’ Chronic Loneliness on Motivation and Emotion Regulation in Social Situations. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zichermann, G. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in Gamification. Available online: http://www.gamification.co/2011/10/27/intrinsic-and-extrinsic-motivation-in-gamification/ (accessed on 9 January 2018).

- ChanLin, L. Applying motivational analysis in a Web-based course. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2009, 46, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, N. The use of GBL to teach mathematics in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2017, 54, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Armstrong, M.B. Enhancing instructional outcomes with gamification: An empirical test of the Technology-Enhanced Training Effectiveness Model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, A.S. Children’s Health, The Nation’s Wealth: Assessing and Improving Child Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shegog, R.; Craig Rushing, S.; Gorman, G.; Jessen, C.; Torres, J.; Lane, T.L.; Gaston, A.; Revels, T.K.; Williamson, J.; Peskin, M.F.; et al. NATIVE-It’s Your Game: Adapting a Technology-Based Sexual Health Curriculum for American Indian and Alaska Native youth. J. Prim. Prev. 2017, 38, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapp, K. Gamification: Separating Fact From Fiction. Chief Learn. Off. 2014, 13, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, D.A.; Gentile, J.R. Violent video games as exemplary teachers: A conceptual analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, D.J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Schneider, B.; Shernoff, E.S. Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. In Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Springer: Dordretch, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 475–494. [Google Scholar]

| 120 students from three classes were randomly selected to participated in the study | 40 students randomly assigned to experiment condition | Pre-test: students given ASHLT before learning | Experiment: students attended sexual health education delivered using GBL | Post-test: students were given the same ASHLT after learning |

| 40 students randomly assigned to experiment condition | Pre-test: students given ASHLT before learning | Experiment: students attended sexual health education delivered using gamification | Post-test: students were given the same ASHLT after learning | |

| 40 students randomly assigned to control condition | Pre-test: students given ASHLT before learning | Control: students attended sexual health education delivered using traditional teaching | Post-test: students were given the same ASHLT after learning |

| Gender | Frequency (%) |

| Male | 63 (52.5%) |

| Female | 57 (47.5%) |

| Age | Mean (SD) |

| Male | 14.2 (0.924) |

| Female | 13.9 (0.963) |

| Living condition | Frequency (%) |

| With both parents | 80 (66.7%) |

| With father only | 7 (5.8%) |

| With mother only | 21 (17.5%) |

| With guardian only | 12 (10%) |

| Economic condition | Frequency (%) |

| We are among the well-off in the area | 24 (20%) |

| We are not rich, but we manage to live well | 62 (51.7%) |

| We are neither rich nor poor, but just about average | 34 (28.3%) |

| We struggle with the strict minimum required to make ends meet | 0 (0%) |

| Access to computer at school or home | Frequency (%) |

| Yes | 82 (68.3%) |

| No | 38 (31.7%) |

| Access to smart devices at school or home | Frequency (%) |

| Yes | 66 (55%) |

| No | 54 (45%) |

| Play of computer or mobile phone games | Frequency (%) |

| Yes | 77 (64.2%) |

| No | 43 (35.8%) |

| Motivation | Component | Measure | TT | GBL | GM | Sig. Kruskal Wallis | Pairwise Comparison | p Value | |

| TM1 | TM2 | ||||||||

| Attention | Mean | 2.55 | 4.43 | 4.40 | 0.001 | TT | GM | 0.001 | |

| SD | 1.16 | 0.37 | 0.40 | GBL | 0.001 | ||||

| Relevance | Mean | 2.76 | 4.47 | 4.55 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.73 | 0.32 | 0.41 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Confidence | Mean | 3.65 | 4.63 | 4.42 | 0.001 | TT | GM | 0.004 | |

| SD | 1.12 | 0.32 | 0.52 | GBL | 0.001 | ||||

| Satisfaction | Mean | 3.67 | 4.53 | 4.56 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0.30 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Attitude | Component | Measure | TT | GBL | GM | Sig. Kruskal-Wallis | Pairwise Comparison | p Value | |

| TM1 | TM2 | ||||||||

| Affective Attitude | Mean | 3.64 | 4.69 | 4.84 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 1.03 | 0.35 | 0.19 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Cognitive Attitude | Mean | 3.51 | 4.76 | 4.77 | 0.001 | TT | GM | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.94 | 0.25 | 0.22 | GBL | 0.001 | ||||

| Knowledge | Component | Measure | TT | GBL | GM | Sig. Kruskal-Wallis | Pairwise Comparison | p Value | |

| TM1 | TM2 | ||||||||

| Importance of knowledge | Mean | 3.13 | 4.79 | 4.84 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 1.13 | 0.23 | 0.20 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Effectiveness of knowledge | Mean | 2.85 | 4.76 | 4.88 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.95 | 0.34 | 0.26 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Application of knowledge | Mean | 3.97 | 4.78 | 4.84 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.28 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Engagement | Component | Measure | TT | GBL | GM | Sig. Kruskal-Wallis | Pairwise Comparison | p Value | |

| TM1 | TM2 | ||||||||

| Emotional engagement | Mean | 2.77 | 4.63 | 4.67 | 0.001 | TT | GBL | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.96 | 0.33 | 0.28 | GM | 0.001 | ||||

| Cognitive engagement | Mean | 2.98 | 4.67 | 4.64 | 0.001 | TT | GM | 0.001 | |

| SD | 0.79 | 0.40 | 0.37 | GBL | 0.001 | ||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haruna, H.; Hu, X.; Chu, S.K.W.; Mellecker, R.R.; Gabriel, G.; Ndekao, P.S. Improving Sexual Health Education Programs for Adolescent Students through Game-Based Learning and Gamification. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092027

Haruna H, Hu X, Chu SKW, Mellecker RR, Gabriel G, Ndekao PS. Improving Sexual Health Education Programs for Adolescent Students through Game-Based Learning and Gamification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(9):2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092027

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaruna, Hussein, Xiao Hu, Samuel Kai Wah Chu, Robin R. Mellecker, Goodluck Gabriel, and Patrick Siril Ndekao. 2018. "Improving Sexual Health Education Programs for Adolescent Students through Game-Based Learning and Gamification" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 9: 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092027

APA StyleHaruna, H., Hu, X., Chu, S. K. W., Mellecker, R. R., Gabriel, G., & Ndekao, P. S. (2018). Improving Sexual Health Education Programs for Adolescent Students through Game-Based Learning and Gamification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092027