Combined Before-and-After Workplace Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in Healthcare Workers (STI-VI Study): Short-Term Assessment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Aim

2. Materials and Methods

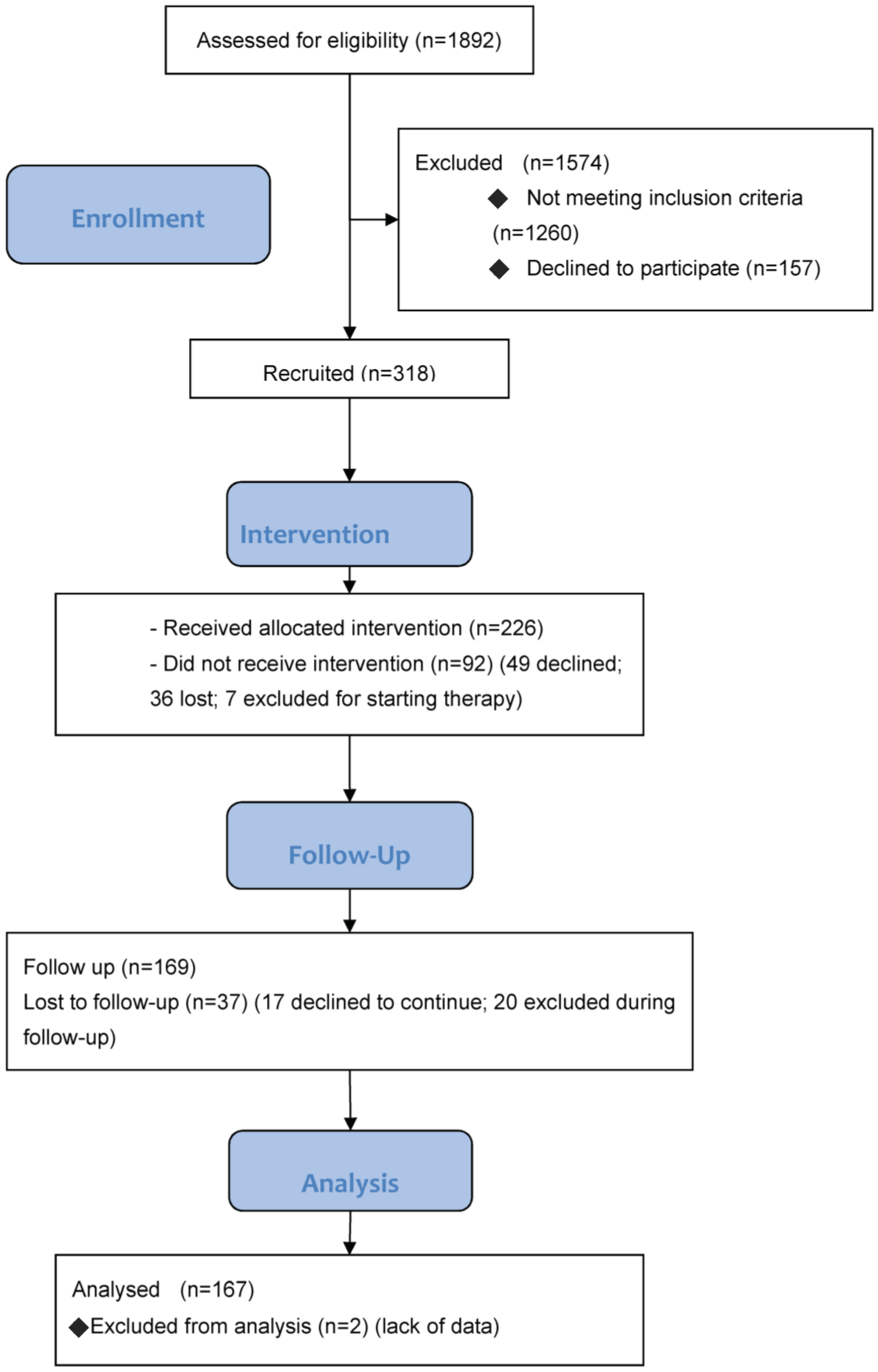

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

- overweight or obesity: a body mass index (BMI) > 25, or a waist circumference > 102 cm in men, or >88 cm in women;

- dyslipidemia: total cholesterol > 220 mg/dL, or high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol < 35 mg/dL, or low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol > 130 mg/dL, or triglycerides > 200 mg/dL, without pharmacological treatment;

- impaired fasting glucose (IFG) levels and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), or diabetes mellitus, without pharmacological treatment.

2.3. Measurements

- current use of medication;

- physical activity: measured in terms of type, frequency (days/week), and duration (in minutes). To ascertain the energy expenditure for this physical activity, we converted these data into Metabolic Equivalent (MET) on the basis of the “Compendium of Physical Activities” [24]. Total calorie consumption was calculated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [25] formulaΣ (MET * frequency * duration)

- blood pressure: systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured three times on the left arm, with the subject seated and at rest for five minutes. The average of the second and third readings was recorded;

- waist circumference: measured to the nearest centimeter using a flexible steel tape, at the end of expiration, placing the tape on a level with the umbilicus [26];

- BMI: height and weight were measured with subjects barefoot and lightly dressed, and their BMI was calculated according to the formula: weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared;

- cholesterol (total, LDL, HDL), triglyceride and blood glucose levels: plasma total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose were measured using standard enzymatic methods. For patients whose triglyceride levels were higher than 400 mg/dL, the LDL level was considered as missing.

- -

- a four-day Food and Physical Activity Diary [27]. Participants were given a food diary in which they were asked to report everything they ate and drank during two working days and two days off work within the week afterwards. They had to record quantities of food as faithfully as possible (in grams or standard portions) and any physical activity (type and duration). The data on participants’ diets were processed using the MètaDieta software approved by the ADI (Italian Association of Dietetics and Clinical Nutrition). This software runs calculations relating to food chemistry (quali-quantitative characterization), basal metabolism, BMI, energy requirements, and food portions. The software is based on official databases for the Italian population as at 2014 (INRAN—National Institute for Food and Nutrition Research—2008 revision; and LARN—Reference Nutrient and Energy Intake Levels) covering a total of 4500 foods and recipes, 114 bromatological components, and photographs of foods and recipes [28]. The analysis conducted on these data is not reported in the present paper;

- -

- a food questionnaire from the PREDIMED trial. This Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) contains 14 questions designed to assess the degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet [29]. The questions investigate daily/weekly doses of nutrients such as fruit, vegetables, condiments (oil), meat, fats, etc., and generate a total score. The higher the score, the more the respondent’s eating habits come close to the Mediterranean model;

- -

- at the time of the visit (T1 and T2), HCWs had to complete an anonymous satisfaction questionnaire containing four questions with yes/no answers, and the opportunity to add any comments/suggestions. The questions investigated whether the intervention had changed their lifestyles (Question 1), and sufficed to modify their eating habits and/or increase their physical activity levels (Question 2). Then there were specific questions about compliance with the timing of the meetings (Question 3), and whether the material received (food pyramid, brochure, etc.) had been adequate (Question 4). Participants were also asked whether the menus available at the workplace canteen favored their adherence to the dietary recommendations they had received.

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Six-Month Follow-up

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Istat Bilancio Demografico Nazionale 2017. Available online: www.istat.it/it/files/2018/02/Indicatoridemografici2017 (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- WHO—Workplace Health Promotion. Available online: www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/workplace/en (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Eurostat—Newsrelease 68/2018. 20 April 2018. Available online: www.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Groeneveld, I.F.; Proper, K.I.; van der Beek, A.J.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; van Mechelen, W. Lifestyle-focused interventions at the workplace to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease—A systematic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 36, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leijten, F.R.M.; van den Heuvel, S.G.; Ybema, J.F.; van der Beek, A.J.; Robroek, S.J.W.; Burdorf, A. The influence of chronic health problems on work ability and productivity at work: A longitudinal study among older employees. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2014, 40, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejlertsson, L.; Heijbel, B.; Ejlertsson, G.; Andersson, I. Recovery, work-life balance and work experiences important to self-rated health. A questionnaire study on salutogenic work factors among Swedish primary health care employees. Work 2018, 59, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N. Obstacles and Future Prospects: Considerations on Health Promotion Activities for Older Workers in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SIMLII. Promozione Della Salute nei Luoghi di Lavoro. Strumenti di Orientamento e Aggiornamento in Medicina del Lavoro; Apostoli, P., Bertazzi, P.A., Imbriani, M., Soleo, L., Violante, F., Eds.; Technical Assessment; Nuova Editrice Berti: Piacenza, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, S.L.; Thompson Coon, J.; Fleming, L.E.; Carroll, L.; Bethel, A.; Wyatt, K. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamisa, N.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D.; Oldenburg, B. Work related stress, burnout, job satisfaction and general health of nurses: A follow-up study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2016, 22, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CERGAS Bocconi. Le Inidoneità e le Limitazioni Lavorative del Personale SSN—Dimensioni del Fenomeno e Proposte; Università Bocconi: Milano, Italy, 10 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Han, T.S.; Schouten, J.S.; Lean, M.E.; Seidell, J.C. The prevalence of low back pain and association with body fatness, fat distribution and height. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1997, 21, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, C.C.; Waters, T.R. A review of work schedule issues and musculoskeletal disorders with an emphasis on the healthcare sector. Ind. Health 2008, 46, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, R.M.; Westmorland, M.G.; Lin, C.A.; Schmuck, G.; Creen, M. Effectiveness of workplace rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of work-related low back pain: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsdottir, I.H.; Börjesson, M.; Ahlborg, G., Jr. Healthcare workers’ participation in a healthy-lifestyle-promotion project in western Sweden. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Bogt, N.C.; Milder, I.E.; Bemelmans, W.J.; Beltman, F.W.; Broer, J.; Smit, A.J.; van der Meer, K. Changes in lifestyle habits after counselling by nurse practitioners: 1-year results of the Groningen Overweight and Lifestyle study. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grandes, G.; Sanchez, A.; Montoya, I.; Ortega Sanchez-Pinilla, R.; Torcal, J.; PEPAF Group. Two-year longitudinal analysis of a cluster randomized trial of physical activity promotion by general practitioners. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijg, J.M.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Verheijden, M.W.; van der Zouwe, N.; de Vries, J.D.; Middelkoop, B.J.; Crone, M.R. Factors influencing primary health care professionals’ physical activity promotion behaviors: A systematic review. Int. J. Beahav. Med. 2015, 22, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral Counseling to Promote a Healthful Diet and Physical Activity for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Adults without Cardiovascular Risk Factors. JAMA 2017, 318, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, K.; Watson, D.; Gedikli, C. Well-Being and the Social Environment of Work: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpavičiūtė, S.; Macijauskiene, J. The Impact of Arts Activity on Nursing Staff Well-Being: An Intervention in the Workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogstad, M.; Lunde, L.-K.; Ulvestad, B.; Ulvestad, B.; Aass, H.C.D.; Clemm, T.; Mamen, A.; Skare, Ø. The Effect of a Leisure Time Physical Activity Intervention Delivered via a Workplace: 15-Month Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetzel, R.Z.; Ozminkowski, R.J. The health and cost benefits of work site health-promotion programs. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Compendium of Physical Activities. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/compendiumofphysicalactivities/Activity-Categories (accessed on 30 August 2017).

- Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the InternationalPhysical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Short Form 2004. Available online: http://www.institutferran.org/documentos/scoring_short_ipaq_april04.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2017).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Anthropometry Procedures Manual. 2007. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2017).

- Binetti, P.; Marcelli, M.; Baisi, R. Manuale di Nutrizione Clinica e Scienze Dietetiche e Applicate; Società Editrice Universo: Roma, Italy, 2006; pp. 135–139. ISBN 978-8889548189. [Google Scholar]

- Software Mètadieta. Available online: http://www.metadieta.it/software (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Martínez-González, M.A.; García-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schröder, H.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: The PREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zenobia Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Moore, S.; Pratt, I.S. Adults and children prefer a plate food guide relative toa pyramid. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008; WHO Document Production Services: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- The Facts about High Blood Pressure. Available online: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/GettheFactsAboutHighBloodPressure/The-Facts-About-High-Blood-Pressure_UCM_002050_Article.jsp#.W1cQAMJlPcs (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Lee, W.W.M.; Choi, K.C.; Yum, R.W.Y.; Yu, D.S.F.; Chair, S.Y. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on lifestyle modification and health outcome of clients at risk or diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Bogt, N.C.W.; Bermelmans, W.J.E.; Beltman, F.W.; Broer, J.; Smit, A.J.; van der Meer, K. Preventing weight gain. One-year results of a randomized lifestyle intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, J.R.; Faber, A.; Ekner, D.; Overgaard, K.; Holtermann, A.; Søgaard, K. Diet, physical exercise and cognitive behavioral training as a combined workplace based intervention to reduce body weight and increase physical capacity in health care workers—A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mecca, M.S.; Moreto, F.; Burini, F.H.P.; Dalanesi, R.C.; McLellan, K.C.P.; Burini, R.C. Ten-week lifestyle changing program reduces several indicators for metabolic syndrome in overweight adults. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2012, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, W.; Sund, M.; Doering, A.; Ernst, E. Leisure-time physical activity but not work-related physical activity is associated with decreased plasma viscosity. Results from a large population sample. Circulation 1997, 95, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Fisac, J.L.; Guallar-Castillòn, P.; Dièz-Gañan, L.; Lòpez Garcìa, E.; Banegas Banegas, J.R.; Rodrìguez Artalejo, F. Work-related physical activity is not associated with body mass index and obesity. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, S.; Song, M.K.; Lee, S.-J. Relationships of musculoskeletal symptoms, sociodemographics, and body mass index with leisure-time physical activity among nurses. Work. Health Saf. 2018, accepted in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouvonen, A.; Kivimaki, M.; Elovainio, M.; Virtanen, M.; Linna, A.; Vahtera, J. Job strain and leisure-time physical activity in female and male public sector employees. Prev. Med. 2005, 41, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lallukka, T.; Lahelma, E.; Rahkonen, O.; Roos, E.; Laaksonen, E.; Martikainen, P.; Head, J.; Brunner, E.; Mosdol, A.; Marmot, M.; et al. Associations of job strain and working overtime with adverse health behaviors and obesity: Evidence from the Whitehall II Study, Helsinki Health Study, and the Japanese Civil Servants Study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1681–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lallukka, T.; Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, S.; Kaila-Kangas, L.; Pitkaniemi, J.; Luukkonen, R.; Leino-Arjas, P. Working conditions and weight gain: A 28-year follow-up study of industrial employees. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 23, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransson, E.I.; Heikkila, K.; Nyberg, S.T.; Zins, M.; Westerlund, H.; Westerholm, P.; Väänänen, A.; Virtanen, M.; Vahtera, J.; Theorell, T.; et al. Job strain as a risk factor for leisure-time physical inactivity: An individual-participant metaanalysis of up to 170,000 men and women: The IPD-work consortium. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.; Trinkoff, A.M.; Geiger-Brown, J. Factors associated with work-related fatigue and recovery in hospital nurses working 12-h shifts. Work. Health Saf. 2014, 62, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Liang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Andersen, L.L.; Szeto, G. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms of the neck and upper extremity among dentists in China. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pattyn, N.; Cornelissen, V.A.; Toghi Eshghi, S.R.; Vanhees, L. The effect of exercise on the cardiovascular risk factors constituting the metabolic syndrome. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackford, K.; Jancey, J.; Lee, A.H.; James, A.P.; Waddell, T.; Howat, P. Home-based lifestyle intervention for rural adults improves metabolic syndrome parameters and cardiovascular risk factors: A randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeneveld, I.F.; Proper, K.I.; van der Beek, A.J.; van Mechelen, W. Sustained body weight reduction by an individual-based lifestyle intervention for workers in the construction industry at risk for cardiovascular disease: Results of randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Blaha, M.J.; Nasir, K.; Rivera, J.J.; Blumenthal, R.S. Effects of Physical Activity on Cardiovascular Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, G.A.; Kelley, K.S.; Vu Tran, Z. Aerobic exercise, lipids and lipoproteins in overweight and obese adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 2005, 29, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merril, R.M.; Anderson, A.; Thygerson, S.M. Effectiveness of the worksite wellness program on health behaviors and personal health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 1008–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Lee, J.G.; Carmona, N.E.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Shekotikhina, M.; Mansur, R.B.; Brietzke, E.; Lee, J.-H.; Ho, R.C.; et al. Efficacy of Antidpressants on Measures of Workplace Functioning in Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, C.C.; Chew, P.K.H.; Lai, S.-M.; Soo, S.-C.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C.; Wong, R.C. Effect of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Quality of Life, Depression and Anxiety in Asian Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total N = 167 Mean ± SD | Male N = 53 Mean ± SD | Female N = 114 Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.0 ± 7.3 | 50.5 ± 8.3 | 49.7 ± 6.8 |

| Pack year (N) | 3.5 ± 8.4 | 4.2 ± 11.9 | 3.2 ± 6.1 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 129.8 ± 13.4 | 137.3 ± 14.5 | 126.4 ± 11.3 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 83.0 ± 7.6 | 88.7 ± 7.2 | 80.4 ± 6.3 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.5 ± 12.0 | 95.5 ± 10.5 | 88.3 ± 12.0 |

| BMI (cm2/kg) | 27.1 ± 4.3 | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 27.4 ± 4.2 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 216.1 ± 32.0 | 213.8 ± 26.7 | 218.1 ± 34.0 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 58.9 ± 16.0 | 50.4 ± 14.0 | 63.2 ± 15.4 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 146.1 ± 28.5 | 147.2 ± 22.8 | 146.4 ± 30.5 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 113.8 ± 57.8 | 132.8 ± 71.2 | 104.7 ± 46.5 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 96.9 ± 10.6 | 99.8 ± 10.1 | 95.2 ± 10.4 |

| Physical activity (MET) | 497.3 ± 729.6 (2400; 7875) * | 778.9 ± 1009.4 (4000; 1050) * | 370.5 ± 519.0 (2250; 540) * |

| Variable | Before Mean ± SD | After Mean ± SD | Difference Mean ± SD | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Physical activity (MET) | 497.3 ± 729.6 (240.0; 787.5) * | 619.6 ± 747.8 (402.5; 868.75) * | 121.2 ± 600.4 (0; 337.5) * | 0.01 |

| Dietary | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Anthropometric factors | ||||

| Waist circumference(cm) | 90.5 ± 12.0 | 88.0 ± 11.5 | −2.5 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| BMI (cm2/kg) | 27.1 ± 4.3 | 26.9 ± 4.4 | −0.2 ± 1.3 | 0.03 |

| Metabolic factors | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 216.1 ± 31.9 | 203.9 ± 31.4 | −12.8 ± 23.2 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 58.9 ± 16.0 | 55.5 ± 14.5 | −3.4 ± 8.0 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 146.1 ± 28.5 | 137.3 ± 29.6 | −9.4 ± 22.6 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 113.8 ± 57.8 | 112.8 ± 89.0 | −1.1 ± 85.5 | 0.87 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 96.9 ± 10.6 | 95.2 ± 9.6 | −1.5 ± 9.9 | 0.05 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 129.8 ± 13.4 | 125.4 ± 13.4 | −4.4 ± 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 83.0 ± 7.6 | 80.5 ± 8.7 | −2.5 ± 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Before Mean ± SD | After Mean ± SD | Difference Mean ± SD | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALE Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Physical activity (MET) | 778.9 ± 1009.2 (400; 1050) * | 860.7 ± 913.2 (600; 866.25) * | 81.8 ± 673.8 (0; 390) * | 0.4 |

| Dietary (N) | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 0.9 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Anthropometric factors | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 95.5 ± 10.5 | 93.7 ± 10.8 | −1.7 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| BMI (cm2/kg) | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 26.5 ± 4.6 | −0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Metabolic factors | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 213.8 ± 26.7 | 204.2 ± 28.1 | −9.6 ± 19.8 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 50.4 ± 14.0 | 47.7 ± 13.0 | −2.7 ± 5.6 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 147.2 ± 22.8 | 138.3 ± 29.8 | −8.9 ± 23.9 | 0.009 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 132.8 ± 71.2 | 147.3 ± 138.9 | 14.5 ± 140.8 | 0.5 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 99.8 ± 10.1 | 98.3 ± 9.6 | −1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.2 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 137.3 ± 14.5 | 130.9 ± 15.0 | −6.4 ± 15.3 | 0.004 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 88.7 ± 7.2 | 85.2 ± 9.2 | −3.5 ± 9.0 | 0.007 |

| FEMALE Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Physical activity (MET) | 370.5 ± 519.0 (225, 540) * | 509.6 ± 633.5 (360, 600) * | 139.1 ± 566.1 (0, 330) * | 0.01 |

| Dietary (N) | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 0.8 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Anthropometric factors | ||||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88.3 ± 12.0 | 85.4 ± 10.9 | −2.9 ± 4.7 | <0.001 |

| BMI (cm2/kg) | 27.4 ± 4.2 | 27.1 ± 4.4 | −0.3 ± 1.5 | 0.04 |

| Metabolic factors | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 218.1 ± 34.0 | 203.7 ± 33.1 | −14.3 ± 24.6 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 63.2 ± 15.4 | 59.3 ± 13.6 | −3.8 ± 8.9 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 146.4 ± 30.5 | 136.8 ± 29.6 | −9.6 ± 22.1 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 104.7 ± 46.5 | 95.9 ± 39.8 | −8.7 ± 33.4 | 0.008 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 95.2 ± 10.4 | 93.7 ± 9.3 | −1.5 ± 10.3 | 0.13 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 126.4 ± 11.3 | 112.9 ± 11.8 | −3.5 ± 12.9 | 0.005 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.4 ± 6.3 | 78.3 ± 7.5 | −2.1 ± 8.7 | 0.02 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scapellato, M.L.; Comiati, V.; Buja, A.; Buttignol, G.; Valentini, R.; Burati, V.; La Serra, L.; Maccà, I.; Mason, P.; Scopa, P.; et al. Combined Before-and-After Workplace Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in Healthcare Workers (STI-VI Study): Short-Term Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092053

Scapellato ML, Comiati V, Buja A, Buttignol G, Valentini R, Burati V, La Serra L, Maccà I, Mason P, Scopa P, et al. Combined Before-and-After Workplace Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in Healthcare Workers (STI-VI Study): Short-Term Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(9):2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092053

Chicago/Turabian StyleScapellato, Maria Luisa, Vera Comiati, Alessandra Buja, Giulia Buttignol, Romina Valentini, Valentina Burati, Lucia La Serra, Isabella Maccà, Paola Mason, Pasquale Scopa, and et al. 2018. "Combined Before-and-After Workplace Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in Healthcare Workers (STI-VI Study): Short-Term Assessment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 9: 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092053

APA StyleScapellato, M. L., Comiati, V., Buja, A., Buttignol, G., Valentini, R., Burati, V., La Serra, L., Maccà, I., Mason, P., Scopa, P., Volpin, A., Trevisan, A., & Spinella, P. (2018). Combined Before-and-After Workplace Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in Healthcare Workers (STI-VI Study): Short-Term Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 2053. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092053