Development of a Complex Intervention for the Maintenance of Postpartum Smoking Abstinence: Process for Defining Evidence-Based Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Need for Relapse Prevention Support

“I think it’s after pregnancy you’re most likely to go back to smoking because you’re detached from the baby, so you feel like you can distance yourself. And I think that’s when the work needs to be done to stay smoke-free because I know I certainly could have gone back to smoking quite easily…because as a smoker, I know what that release feels like, and you’re like ‘I just want to smoke, I just feel like that again,’ and everything can be all right for half an hour”.(034, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think you could frame the relapse prevention stuff in a really positive way. When you’ve already done this really difficult thing, giving up smoking, to give babies the best chance in pregnancy, and for me starting off on a positive note like that makes me more likely to, kind of, engage with information rather than, stuff about quitting starts from quite a negative standpoint a lot of the time. How bad smoking is rather than how good it is when you quit and how to help you stay quit”.(FG 006–008, postpartum ex-smoker)

“Because they need that continuous drip feeding, like we’ve already said, from the midwife they see post-birth, to the GP they see at six weeks, to the health visitor that they see, or the nursery nurse that goes in and does baby massage, they need to be able to access that support”.(HCP FG 011)

3.2. ‘Who’ Should Introduce Support and ‘When’?

“hearing it from an actual professional, you know like a health professional then you know, you’re going to believe them over, I don’t know, someone else, aren’t you?”(053, pregnant ex-smoker)

“I think the timing is probably quite key. If it was probably at this point, I’d be happy, I’m nearly seven months, I’d probably be happy to sit for ten minutes and discuss it with somebody”.(041, pregnant relapser)

“I think at your last midwife appointment, which I think is about 32 weeks you go. It would be like your last midwife and then you’re kind of handed over to delivery—after that, that would be—obviously keep the conversation going during pregnancy but that would be the time to say look, here’s some information about staying smoking free after you’ve had the baby”.(034, postpartum ex-smoker)

3.3. ‘What Form’ Should Relapse Prevention Support Take?

3.3.1. Online Tailored Self-Help Support

“I think probably a website would be better if I was given just like maybe like a small business card size thing with like a website on that I can visit then I think that would be… yeah, then I could sort of just look in my own time really. I expect a lot of people these days also I think breastfeed with their phones in their hands, looking at the news or Facebook and things”.(021, postpartum relapser)

“that would make them then think, because obviously they talk about more stillbirth and infant deaths more now, but then that’s like trying to find what is causing it and smoking is, well, is one of the reasons”.(037, pregnant ex-smoker)

“The nicotine replacement therapy—again knowing like what’s out there I think, because until again I had that advice and I tried different things then I would have probably just tried to do it cold turkey and that’s, it works for some people but not for everybody. So again, getting the information out there, I think is really key and what works with breastfeeding and what is more child friendly or you know takes the risks away”.(045, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think if it was something like an app where you go in and erm it’s kind of one of these ‘’Give up Smoking’—it tells you how many days you’ve been given up for and it tells you what the benefits are of what you’ve gained from having given up for that period and things like that, and it’s got little visual graphs of, you know, the positives and things like that—then it’s something that I’d probably pop into and have a look”.(041, pregnant relapser)

“the app where they can, where somebody could go and specifically look to see what the harmful risks, and what the dos and don’ts are… maybe so they can actually take it upon themselves, to go and do that”.(049, pregnant relapser)

“What’s really helping me is that figure, that cost of what I’ve saved”.(046, pregnant ex-smoker)

3.3.2. Digital/Text Message Support

“If you get a text message, everyone is straight on their phone. You know you hear an iPhone go off in like (place) town or something, or in a supermarket, and it’s all dinging and everyone’s like oh, is that my phone?! So as I said, really useful”.(044, pregnant ex-smoker)

“Yeah I think using the person’s name is definitely—I mean there’s so much you know, we get so much kind of stuff marketed at us in this day and age, sort of digital marketing and that so I think yeah, I think definitely, you’d want probably a personal approach, you know. There’s no mistake, you know you’re getting it through text message onto your phone and it’s speaking directly to you so yeah, I think that probably is important to personalise the message”.(022, partner to pregnant relapser)

“I suppose once you’ve got into it a little bit and you feel like you don’t need as much help, then I suppose that could start to then tailor down. And that could tie in quite a bit with the relapsing part, so to speak, I suppose because if then you feel like you’re not doing well, you could then put on the like reply to the text message saying ‘oh I’ve had a relapse’ and then could then set you back to the three, four day thing but then if you’re doing well that might… maybe you could like do it every sort of five days to a week maybe”.(021, pregnant relapser)

3.4. ‘How Long’ Should Support Continue for?

“The midwives have tick boxes, don’t they, they have to talk to you about and even if it was just a tick box every time you went, the midwife mentions it again—that would be helpful”.(050, postpartum ex-smoker)

“when you see your health visitor, they support you with that as well because they give you information and support on like your breastfeeding and sleeping and other things to do with your child so they could like roll that into one and have the smoking support with that, then I think a lot of women might take to it”.(FG 053-054, pregnant ex-smoker)

3.5. Potential Intervention Components

3.5.1. Relapse Prevention ‘Kit’

“something that’s for them. You know, that’s what they need, it’s something for them and they know there’s help and they know that there’s support. So a little help pack. Mama’s Little Help Pack or Help Kit—that, I think that would go really well because it’s all personal”.(044, pregnant ex-smoker)

3.5.2. Partner Involvement

“I think the best thing a partner can do is quit as well really because after I’d had my oldest child, he was still smoking and he was quite good at first and would say no I’m not, and I’d say oh just give me a cigarette and he’d say no, no, no I’m not but eventually I just pestered him when we were out one day and he gave in and that’s how I started again”.(FG 023–026, postpartum ex-smoker)

“he is very good at reeling facts off at you, but it’s the emotional support that you sometimes need. I knew, you know, people die of lung cancer. I knew that you can get heart failure, I knew of this, that and the other, but that emotional support is missing”.(034, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think that’s quite a strong right approach actually. I mean they say when she was born you’ve got a new name ‘dad’, I mean that’s something important, isn’t it, it’s like a big thing. Isn’t it time you got rid of the other one? The dirty cigarettes and ashtray”.(052, partner)

“even if it’s just to help them help the mum kind of quit, but it is just having that someone to talk to about how they do that, or how they help them quit or how they stand by them”.(051, partner)

3.5.3. Social Support

“I like the Facebook chat thing, things like that, people talking about it on there would probably be more beneficial. People that are going through it”.(042, pregnant ex-smoker)

“I think something maybe online more than in person. I think definitely, you definitely feel as a woman who’s gone back to smoking after having a baby, you do feel a lot of stigma, you do feel a lot of judgement towards yourself and I think maybe going somewhere where you’re in a group physically, you may feel more judged than say if it was online where it’s more anonymous”.(001, pregnant ex-smoker)

3.5.4. E-Cigarettes

“So personally, I don’t think promoting, because it’s still smoking, you’re not taking away that need for smoking, the habit of smoking or the nicotine dependency—you’re replacing it”.(034, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I’m a bit concerned about the lack of long-term data we have on them about the levels of harm”.(FG 006–008, postpartum ex-smoker)

“for some that need it, yes, but i don’t like it. .... far safer?...........relatively harmless?. There’s still risks”.(Online anonymous feedback)

“Erm just knowing that the baby was being free from nicotine. Yeah I don’t know how much that is and how that could affect a baby. Erm, it’s kind of hard to say yeah, but it’s still not good that they’re getting nicotine, I mean even if you’re doing the e-cigarettes, I don’t know what the reduction in risks will be and what the risks are of nicotine through breastmilk for your baby are. So maybe information on that. Erm, I guess you just want to say still breastfeed even if you’re smoking, even if you’re vaping or if you’re not. You know it’s still the best way to feed your baby but erm, yeah I don’t know what the difference of nicotine exposure is through smoking cigarettes and vaping and you know what the effects on the baby are”.(055, postpartum ex-smoker)

3.5.5. Incentives

“I think money would be an added motivation. Every little bit helps.”.(FG 006–008, postpartum ex-smoker)

“Yeah. Gift card. Why don’t you go and treat yourself because, yeah. I remember when after she was first born it was my birthday and [name]’s mum paid for me to get a massage and that was brilliant because I felt really properly spoilt, because you put so much of yourself into everybody else, you know, so yeah that would be a really good incentive I think. Then you can go and do your well-earned gift, or whatever it is, and feel good about yourself, which is what everybody needs, especially if they’re trying to stop smoking”.(004, postpartum ex-smoker)

“it doesn’t sit well with me that people are going to be… I think everybody knows the dangers, I think people do need to be reminded but I don’t think that giving rewards for that, like you say, is it just going to… ‘oh I’ll get my reward this time and then if I do it again, I can stop again and ooh do I get another reward like’”.(009–014 HCP FG)

“to put the money that you would have spent away and then look at how much you’ve got at the end of the month. That’s always a good one”.(050, postpartum ex-smoker)

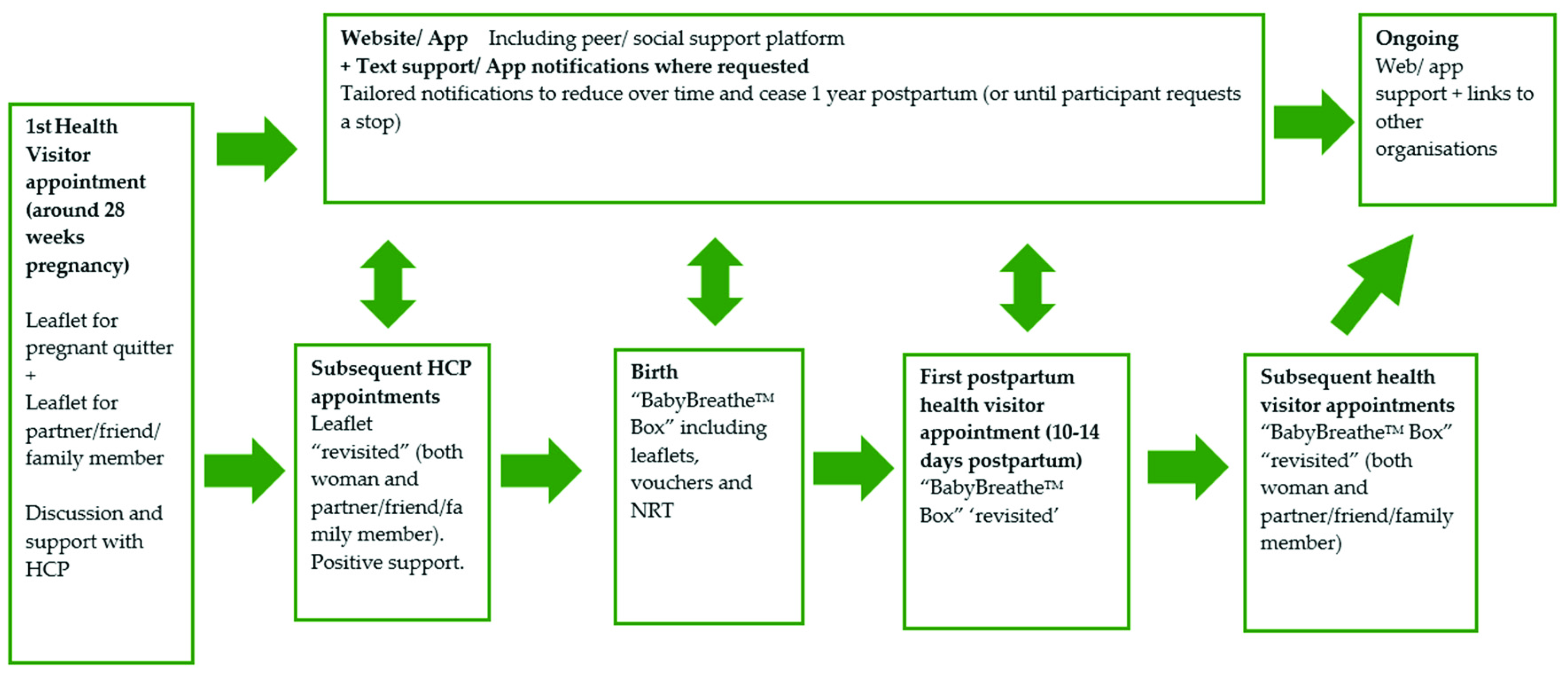

3.6. Phase 3: Person-Based Intervention Development

“we’ve never smoked in our house, going for a dog walk is a chance for us to have a chat, catch up and have a couple of cigarettes on the way round. So actually, when I first gave up, going for a walk was one of my triggers for wanting to have a cigarette”.(058, postpartum ex-smoker)

“It’s mainly just the thing about the partners that’s going to be the most helpful and I think for me would have been the most useful. Erm, just knowing that you know, because then I could have supported him, you know, so, and maybe it’s a platform that you can refer to as a couple and again, it starts that conversation and if it’s got facts and figures on it, I think it’s more likely to, it would have helped me to convince him”.(060, postpartum ex-smoker)

“And then it’s recapped during like your midwife appointments and things like that. I think that’s quite a good way to have it, and the website’s there continuously as well. And that you’ve been informed about it from the start, which is quite good because it gives you a chance to get used to using it and all the different sort of benefits and features of it. And then I think that the Fourth trimester pack (relapse prevention kit), sort of after your baby’s first born, it can be given to you, and then they can go over it with you when they visit and stuff, I think that’s quite good… I think the first year because then it’s all your pregnancy and then a few months afterwards. I think that’s sort of good to keep it going until you sort of have had your baby and then it still encourages you once you’ve had your baby to stay quit”.(063, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think as long as they’re giving the leaflet out and talking to people at the same time”.(062, postpartum ex-smoker)

“you’re kind of already coming from a positive place, aren’t you? Saying thank so much for being that guy, thanks for being that person and you’re given the factual information about kind of why it’s great that you are this person and that you’re doing this and why it’s good for mum and baby. Erm, and you know you’re kind of giving enough information about the programme so you’re saying, we’re not asking you to do it alone with your partner, we’re going to help you do this and this is what we’re going to do to help you do this”.(059, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think for me, and again I think this might just be personal choice, it is the stats information, you know the kind of health, second-hand smoke, you know all those kind of stats, SIDS, increased risk of SIDS—all that kind of information for me, really stands out to me because I know that it’s backed up with research”.(059, postpartum ex-smoker)

“it was personalising it to you and it’s something you can come back to and I think it’s really good so you’re aware of what your trigger points are and when you’re, you know your difficult times”.(060, postpartum ex-smoker)

“But probably more so on my phone than on an actual laptop. Especially if I was, and I had managed to breast feed, it’s probably something that I would have done whilst feeding”.(058, postpartum ex-smoker)

“They were really good, they were good, yeah. Yeah they did help you. I mean I think they would help especially for like if you’re having a bad day and you can just try, because everyone’s on their phones, aren’t they, so just try and distract yourself”.(064, postpartum ex-smoker)

“It’s quite nice to hear my phone. I was like oh who’s messaged me! Oh yeah, look. And I suppose maybe it’s because I’m quite rural so therefore I am at risk of being really quite isolated. That oh yeah, there’s someone there”.(058, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think it would be a good approach because it’s sort of then feels like you’re erm getting additional support and it sort of like gives you a chance to look through things, if you’re not going to use the website or the texting or things like that, it’s quite good to have a box full of the information. And different gifts and things that encourage you”.(062, postpartum ex-smoker)

“it’s always good to know what’s available because I mean like I was saying earlier, going back onto something like patches is so much better than going back onto cigarettes because then it’s only the nicotine you’re getting and it’s not anything else, is it? And I think just being aware of what things are really good. And obviously all the information that you guys have got, you always talk about e-cigs as well so I think it’s good then you’ve got both sides, haven’t you?”(060, postpartum ex-smoker)

“Just explaining what… yeah. What are e-cigarettes, what are the different… the fact that you can have 0% strengths, you can have different variations of nicotine maybe. Yeah I think for a lot of people they might go back to cigarettes rather than that because that all just seems so confusing and complicated if you’ve never used any kind of nicotine replacement”.(066, postpartum ex-smoker)

“I think it would make you feel very supported. Yeah, definitely. A combination of everything, the website, the texts. Erm, the app”.(066, postpartum ex-smoker)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, M.; Lewis, S.; Parrott, S.; Wormall, S.; Coleman, T. Re-starting smoking in the postpartum period after receiving a smoking cessation intervention: A systematic review. Addiction 2016, 111, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notley, C.; Blyth, A.; Craig, J.; Edwards, A.; Holland, R. Postpartum smoking relapse—A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Addiction 2015, 110, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, S.; Coleman, T.; Coleman-Haynes, T.; Ussher, M. Predictors of Postpartum Return to Smoking: A Systematic Review. Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2017, 20, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notley, C.; Colllins, R. Redefining smoking relapse as recovered social identity—Secondary qualitative analysis of relapse narratives. J. Subst. Abuse 2018, 23, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Hardeman, W.; Bauld, L.; Holland, R.; Maskrey, V.; Naughton, F.; Orton, S.; Ussher, M.; Notley, C. Re-configuring Identity Postpartum and Sustained Abstinence or Relapse to Tobacco Smoking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone-Banks, J.; Norris, E.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; West, R.; Jarvis, M.; Hajek, P. Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2, CD003999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, R.; Peto, R.; Boreham, J.; Sutherland, I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004, 328, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peto, R.; Darby, S.; Deo, H.; Silcocks, P.; Whitley, E.; Doll, R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: Combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ 2000, 321, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Are the Health Risks of Smoking? 2018. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/common-health-questions/lifestyle/what-are-the-health-risks-of-smoking/ (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Passive Smoking and Children RCP London. Available online: https://shop.rcplondon.ac.uk/products/passive-smoking-and-children (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Michie, S.; Prestwich, A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2010, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olander, E.K.; Darwin, Z.J.; Atkinson, L.; Smith, D.M.; Gardner, B. Beyond the “teachable moment”—A conceptual analysis of women’s perinatal behaviour change. Women Birth J. Aust. Coll. Midwives 2016, 29, e67–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Morrison, L.; Bradbury, K.; Muller, I. The person-based approach to intervention development: Application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Hardeman, W.; Bauld, L.; Holland, R.; Maskrey, V.; Naughton, F.; Orton SUssher, M.; Notley, C. A systematic review of behaviour change techniques within interventions to prevent return to smoking postpartum. Addict Behav. 2019, 92, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teddlie, C.; Yu, F. Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology with Examples. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, F.; Cooper, S.; Foster, K.; Emery, J.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sutton, S.; Jones, M.; Ussher, M.; Whitemore, R.; Leighton, M.; et al. Large multi-centre pilot randomized controlled trial testing a low-cost, tailored, self-help smoking cessation text message intervention for pregnant smokers (MiQuit). Addiction 2017, 112, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.L.; Szatkowski, L.; Ussher, M. Evaluation of a refined, nationally disseminated self-help intervention for smoking cessation (“quit kit-2”). Nicotine Tob. Res. Off. J. Soc. Res. Nicotine Tob. 2013, 15, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, M.; Chambers, M.; Adams, R.; Croghan, E.; Murray, R. Evaluation of a nationally disseminated self-help intervention for smoking cessation (‘Quit Kit’). Tob. Control. 2011, 20, 380–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group. Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group—A Review of the Challenge. Available online: http://smokefreeaction.org.uk/smokefree-nhs/smoking-in-pregnancy-challenge-group/ (accessed on 30 May 2019).

- NHS Long Term Plan. Available online: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Making Every Contact Count (MECC). Available online: https://www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk/ (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Ashford, K.B.; Hahn, E.; Hall, L.; Rayens, M.K.; Noland, M. Postpartum Smoking Relapse and Secondhand Smoke. Public Health Rep. 2009, 124, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants | Interviews Completed | Online/Email Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Postpartum relapsers | 7 | 2 |

| Postpartum ex-smokers | 16 | 6 |

| Pregnant relapsers | 5 | 0 |

| Pregnant ex-smokers | 9 | 4 |

| Partners | 7 | 2 |

| Did not specify | 0 | 4 |

| Health professionals (Midwives, Health Visitors, Stop smoking advisors) | 12 | 0 |

| 56 | 18 | |

| Total | 74 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Notley, C.; Brown, T.J.; Bauld, L.; Hardeman, W.; Holland, R.; Naughton, F.; Orton, S.; Ussher, M. Development of a Complex Intervention for the Maintenance of Postpartum Smoking Abstinence: Process for Defining Evidence-Based Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111968

Notley C, Brown TJ, Bauld L, Hardeman W, Holland R, Naughton F, Orton S, Ussher M. Development of a Complex Intervention for the Maintenance of Postpartum Smoking Abstinence: Process for Defining Evidence-Based Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(11):1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111968

Chicago/Turabian StyleNotley, Caitlin, Tracey J. Brown, Linda Bauld, Wendy Hardeman, Richard Holland, Felix Naughton, Sophie Orton, and Michael Ussher. 2019. "Development of a Complex Intervention for the Maintenance of Postpartum Smoking Abstinence: Process for Defining Evidence-Based Intervention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 11: 1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111968

APA StyleNotley, C., Brown, T. J., Bauld, L., Hardeman, W., Holland, R., Naughton, F., Orton, S., & Ussher, M. (2019). Development of a Complex Intervention for the Maintenance of Postpartum Smoking Abstinence: Process for Defining Evidence-Based Intervention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(11), 1968. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111968