1. Introduction

Landfills are a major contributor to the world’s anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions because an enormous amount of CH

4 and CO

2 are generated from the degradation process of deposited waste in landfills [

1]. Landfill operation is usually associated with contamination of surface and groundwater by leachate from the landfill (mostly if the landfill lacks adequate liners), pungent odour, loud disturbing noise from landfill bulldozers, bioaerosol emissions; volatile organic compounds [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The storage of leachate in open lagoons can influence the levels of odours experienced in a landfill site. Residents living close to landfill sites have shown concern due to several hazardous pollutants emanating from landfill operations [

8]. Some other pollutants associated with deposition of waste on landfills include litter, dust, excess rodents, unexpected landfill fires, etc. [

9,

10,

11]. The factors that influences the by-product or emissions from landfills include the kind and quantity of waste deposited, the age of the landfill, and the climatic conditions of the landfill sites. Complex chemical and microbiological reactions within the landfill often lead to the formation of several gaseous pollutants, persistent organic pollutants (such as dioxins, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), heavy metals and particulate matter [

8,

10,

11,

12].

The continuous inhalation of CH

4 by humans can cause loss of coordination, nausea, vomiting and high concentration can cause death [

13,

14,

15]. Acidic gases like nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, and halides have harmful effects on the health and environment when introduced [

16]. Studies have shown that when nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide are inhaled or ingested by humans, symptoms such as nose and throat irritations, bronchoconstriction, dysproca and respiratory infections are prevalent, especially in asthmatic patients. These effects can trigger asthma attacks in asthmatic patients [

13,

17,

18,

19]. In addition, high contact of NO

2 by humans increases the susceptibility to respiratory infections [

17]. Furthermore, when these acidic gases reach the atmosphere, they tend to acidify the moisture in the atmosphere and fall down as acid rain. Phadi et al. [

20] identified that sulphur dioxide has harmful effects on plant growth and productivity. In addition, humans are at the risk of reduced lung function, asthma, ataxia, paralysis, vomiting emphyserra and lung cancer when heavy metals are inhaled or ingested. Illnesses like, high blood pressure and anaemia have been shown to be caused by heavy metal pollution [

17,

21,

22]. Additionally, when in contact in high proportions, heavy metals affect the nervous system which causes neurotoxicity leading to neuropathies with symptoms like memory disturbances, sleep disorders, anger, fatigue, head tremors, blurred vision and slurred speech. It can also cause kidney damage like initial tubular dysfunction, risk of stone formation or nephrocalcinosis, and renal cancer. When humans are exposed to a high amount of lead, it can cause injury to the dopamine system, glutamate system and N-methyl-D-Asphate (NMDA) [

17,

21,

22,

23].

Landfills generate different kinds of trace toxic elements which include carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulphide, xylene, dioxin, etc. Toxic organic micro pollutants also include polychlorinated dibenzo-para-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDDs and PCDFs) which are all called dioxins and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Dioxin can be formed from the presence of chlorine-containing substances in the landfill and from landfill fire which is harmful to human health [

10,

17,

24,

25]. Dioxin has been linked with increase in mortality rate caused by ischemic heart disease, when ingested by humans [

23]. PAHs are considered to have potential carcinogenic properties when in contact with humans which could lead to a tumour of the lungs, skin cancer and deficiencies on other parts of the body [

4,

17,

24]. When humans inhale particulate matter, studies have shown that it leads to lining inflammation, systemic inflammatory changes and blood coagulation which can further lead to obstruction of blood vessels, angina and myocardial infraction [

17]. A study conducted in a Turkish landfill, on the health risk assessment of BTEX (Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene, and Xylene) emissions on landfill workers in the area shows that BTEX did not pose a health threat to the landfill workers, because the mean concentration of BTEX measured in the landfill was not sufficient and was lower than the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA’s) generally acceptable excess upper-bound lifetime cancer risk of one in 10,000. However, the author noted that landfill effects on humans directly depended on the type of pollutants and the duration of exposure to the people [

24].

Hydrogen sulphide (H

2S) is a colourless and highly flammable gas. It has an odour of rotten egg and contributes immensely to the odour emissions experienced from landfill sites. It is formed when high sulphate containing compounds (like gypsum and plasterboard) are mixed with the degradable waste in the landfill site. When humans are exposed to high levels of H

2S it could lead to malfunction of the central nervous system and respiratory paralysis [

26].

Waste management has been closely associated with biological hazards. The decomposition of waste materials in the landfill; vehicle exhaust fumes and favourable weather condition can lead to the formation of bioaerosols and biological agents such as fungi, bacteria and volatile compounds (like endotoxins, β(1-3)-glucans and mycotoxins) [

27,

28]. Exposure to bioaerosols has been implicated with various respiratory health diseases which can provoke inflammation of the airways. Several studies have shown that occupational risk of waste handlers and landfill workers are high when compared to others [

27,

29,

30]. Cancer and other respiratory allergies have been reported by communities living closer to landfill sites. Endotoxins are the most powerful proinflammatory component present in bioaerosols, which are components on the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. Heldal et al. [

27], showed that the exposure to low concentration of endotoxins to waste collectors and compost workers can cause an inflammatory response to the upper airways through neutrophil activation and the release of cytokines such as IL6 and IL8 and TNF-alpha. In addition, Gladding et al. [

29] showed that workers exposed to higher amounts of endotoxin and (1→3) -β-D-glucan had an increased risk for respiratory diseases as compared to others with lesser exposure. Most studies focused on biological risk association with waste and landfill workers because of their close proximity to the biological agents over time, therefore, this can be an indication of the possible health risk of people living closer to landfills.

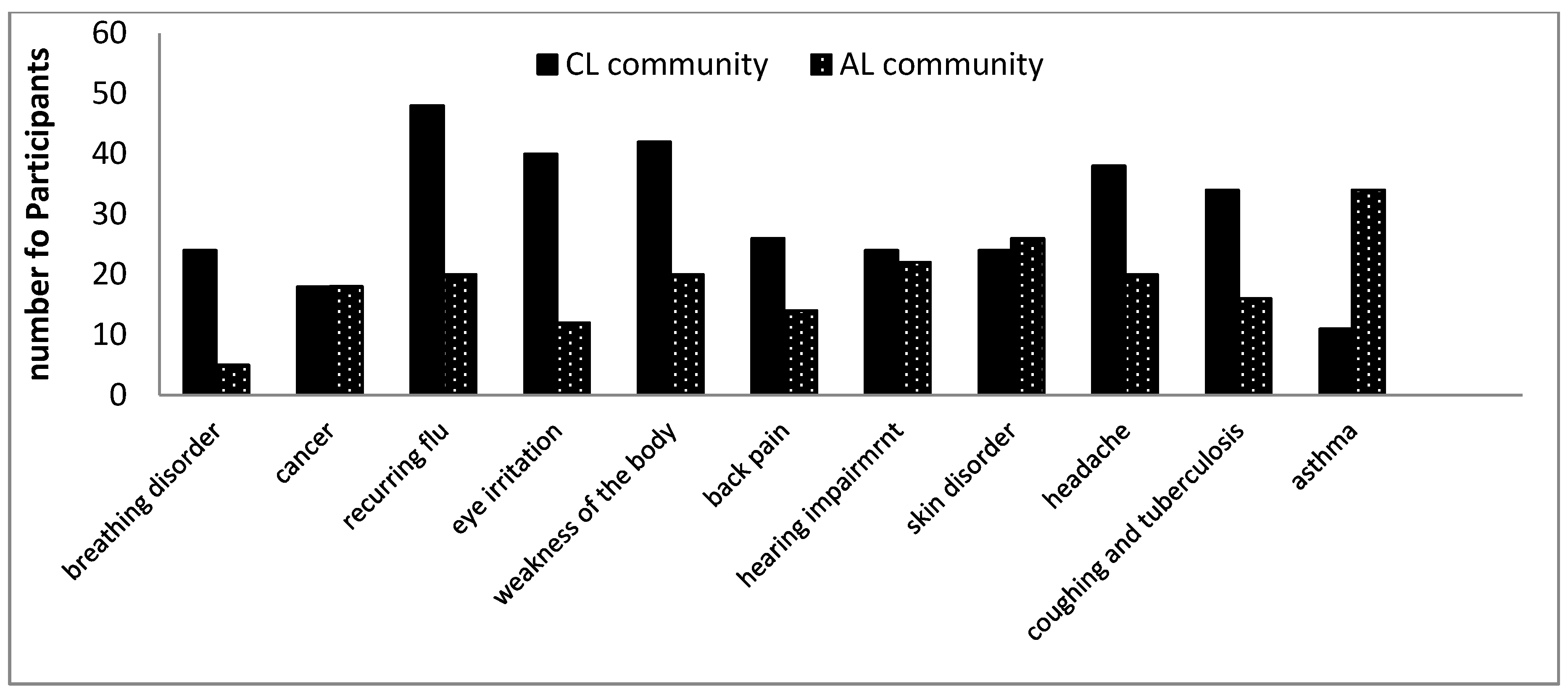

Previous research shows that people living closer to landfill sites suffer from medical conditions such as asthma, cuts, diarrhoea, stomach pain, reoccurring flu, cholera, malaria, cough, skin irritation, cholera, diarrhoea and tuberculosis more than the people living far away from landfill sites [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. The causes of the health problems are as a result of continuous exposure to chemicals; inhalation of toxic fumes and dust from the landfill sites. Additionally, a review on the “residential proximity to environmental hazards and adverse health outcomes” showed a significant correlation between residential proximity to environmental hazards and adverse health outcomes especially risks for central nervous system defects, congenital heart defects, oral defects, low birth weight, cancer, leukaemia, asthma, chronic respiratory symptoms, etc. The author noted that although residents living closer to the landfill appear to be more prone to adverse effects of health outcomes, the proximity does not equate to the individuals’ level of exposure [

36]. The health hazard is dependent on the level of exposure of the residents to the pollutants and concentration of the pollutants. Landfill proximity to residents will also have significant effects on property value in the area [

37,

38,

39,

40].

Despite the proliferation of the harmful effects in recent years, not much research on health and environmental impacts on the residents living closer to landfill sites has been conducted in many landfills situated in rural and peri-urban centres in South Africa. Though, Bridges et al. [

34] conducted a study in comparison of adverse effects of incinerators and landfill emissions on health. The study did not consider the environmental and economic risk and impact associated with landfill pollutants. Therefore, this study posed several relevant questions which are yet to be addressed. These questions include; (a) are there major social-economic differences between the residents living closer to the landfill and residents living far from the landfill? (b) Do the residents living closer to the landfill find the landfill’s characteristics very disturbing compared to those living far from it? (c) Do the residents living closer to the landfill suffer from some specific illnesses more than the residents living far from the landfill? (d) What is the perception in view of the community life satisfaction between residents living closer to the landfill site and residents living far away from it? This study was therefore aimed at investigating and providing answers to the above research questions.

2. Materials and Methods

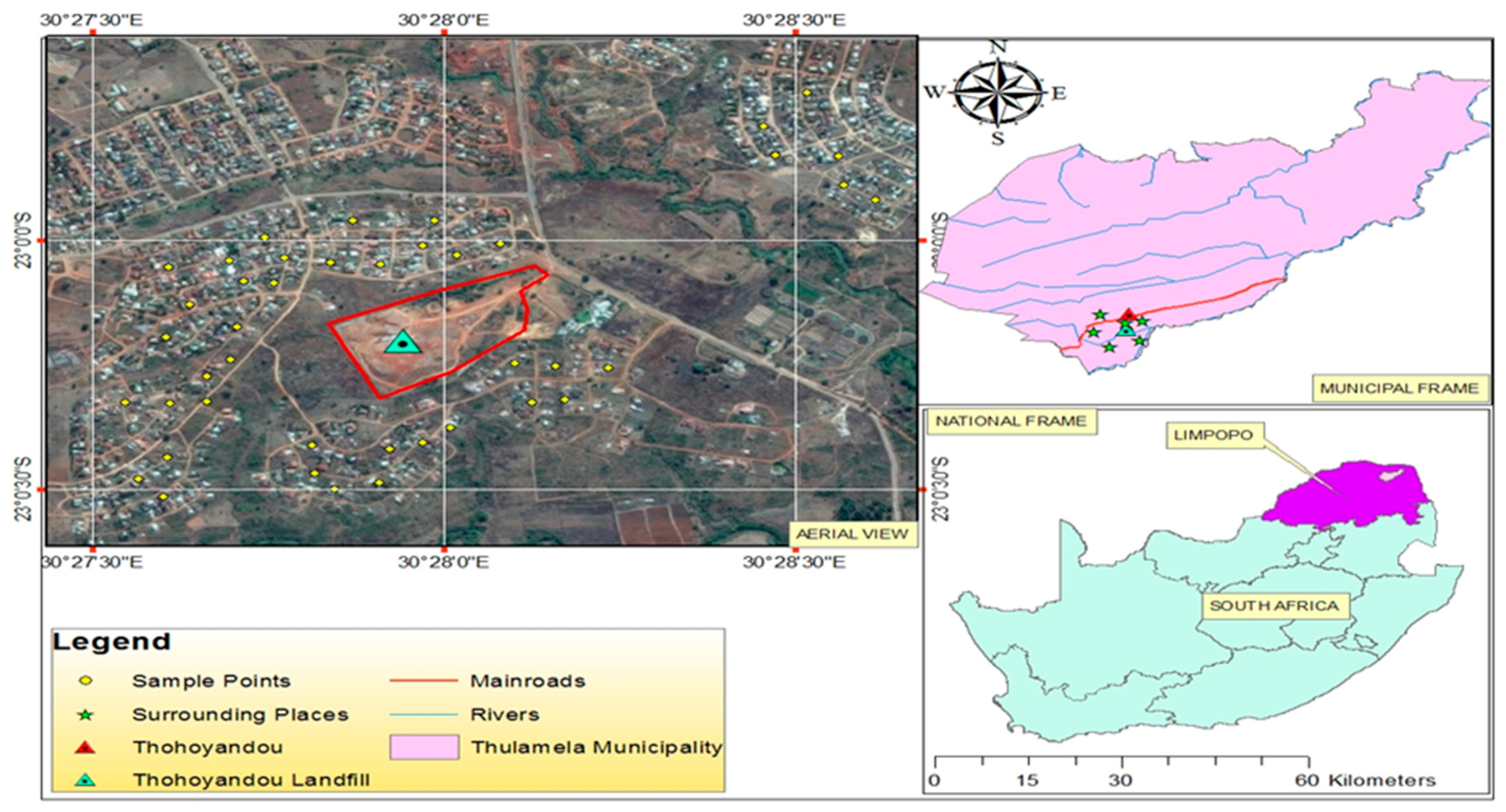

Thohoyandou landfill is situated very close to the residential areas at approximately 100 m away. Therefore, this study sought to find out the perceptions of health impact and the way of life for residents living closer to Thohoyandou landfill. Firstly, a reconnaissance survey was conducted around the landfill site to identify the number of households and other functional institutions located in the area. It was observed that the community was located approximately 100 m away from the landfill. Therefore, the study focused on residents living approximately 100 m to 2 km away from the landfill. The households living closer to the landfill were identified to be approximately 100 households, with an average of four people per household [

41]. Then, the participants of the study were strategically identified based on how long they have lived in the community. This led to 100 people identified as the sample size.

According to Brewer [

42], stratified random sampling technique was adopted to identify approximately 50 participants for the study, who lived approximately 100 to 500 m, and 50 participants were identified as the control for the study who lived within 1 to 2 km away from the landfill.

A landfill operator manager and three university students from the University of Venda, South Africa were trained and recruited for data collection. A five-page questionnaire was pretested with 10 participants to identify errors and limitations of the survey tool. Furthermore, after adjustments of the questionnaire, the questionnaires were administered to a total of 100 participants (50 participants—people living closer to landfill; while 50 participants—people living far away from the landfill). At the start of the administration of questionnaires, the majority of the residents were willing to corporate and participate in the study. Additional information, suggestions and recommendations were also given to the researchers by the participants based on the environmental challenges faced by the community. During the fieldwork, four households expressed scepticism and refused to participate in the study. Two other households expressed less concern because they felt the study was not beneficial to them as they were not house owners and not fully responsible for the environmental issues in the community.

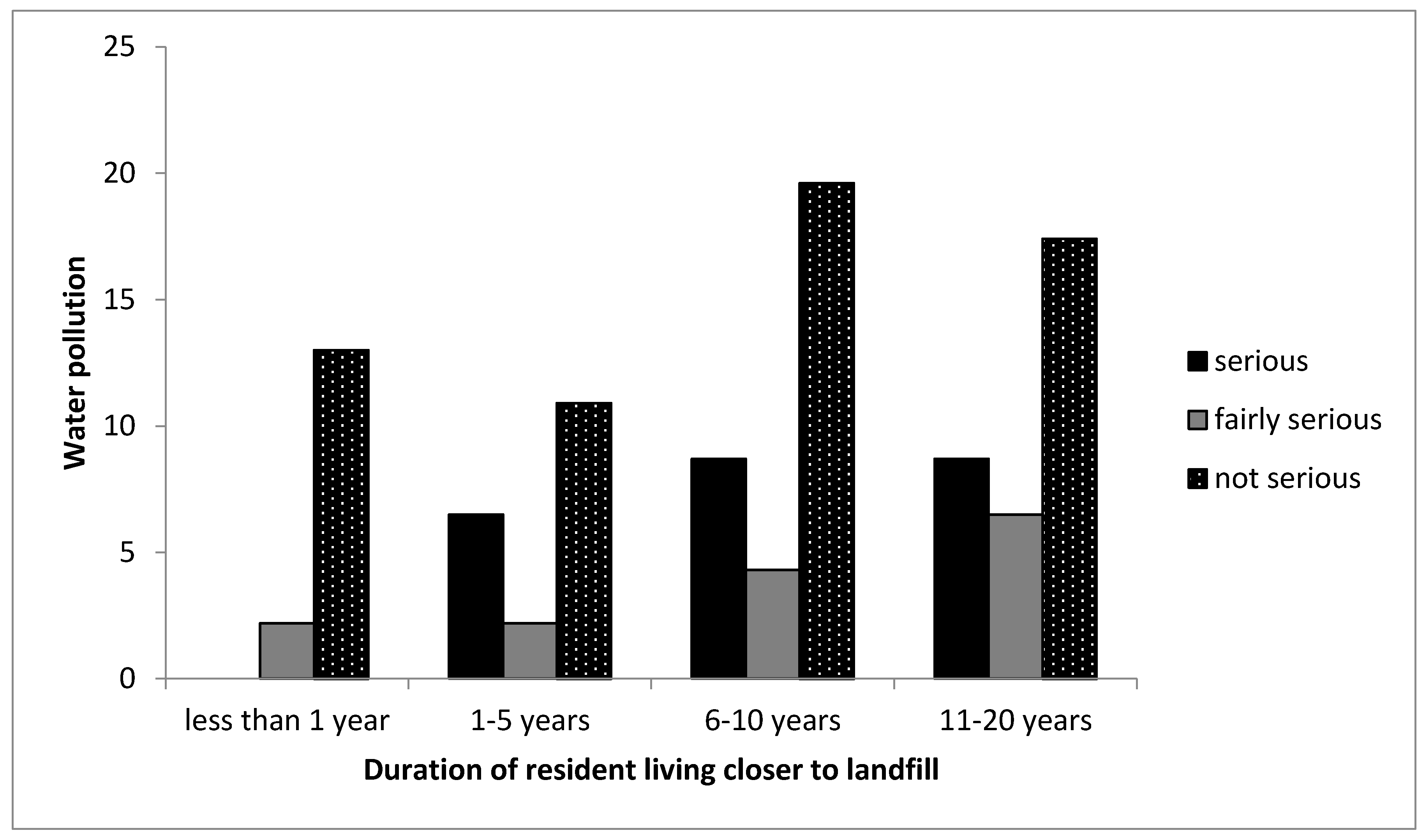

Topical issues on the perception of neighbourhood problems, the significance of environmental problems, most frequently experienced sickness and life in general in the community were identified. The questions asked concerning environmental problems were coded as (1) serious, (2) a fairly serious problem and (3) not a serious problem. The participants were provided with seven environmental issues facing the community which included disposal of solid waste, garbage, and litter in the street, unwelcome location of the landfill, air pollution, bad odour, water pollution, noise pollution and dust. An independent sample

t-test analysis was conducted to identify the difference in mean, and the significance of results obtained from both communities (

Appendix A).

In addition, the participants were presented with possible illnesses associated with complaints of people living closer to the landfill site. The participants were asked to indicate whether they or any member of their family experienced each of the identified illnesses frequently (1), fairly frequently (2) or not frequently (3). The data acquired from the field study were analysed with the aid of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25 developed by International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk City, NY, USA.

Figure 1 shows the location of the study area.

4. Conclusions

The study on health and environmental impacts of landfill sites on humans has generated mixed reactions among scholars, therefore, constitutes a complex study. This study evaluated the health and environmental effects of Thohoyandou landfill on the residents living closer to the landfill, which integrates different factors like waste disposal, air and dust pollution, location of the landfill, water and noise pollution, fear of future health, property value, mosquitoes and rodent’s pollution, life in general in the community, etc.

This study concludes that the residents living closer to the landfill sites are at higher health and environmental risks when compared to those living far away from the landfill sites. However, the landfill associated problems have helped the community living closer to the landfill to be more conscious and educated on environmental pollution. The health risk associated with landfill pollutants in this study shows that proper landfill management is very essential. Landfills should be located far away from residential houses and institutions to avoid certain health and environmental related risks.