Child and Youth Health Literacy: A Conceptual Analysis and Proposed Target-Group-Centred Definition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What target-group-specific characteristics have to be considered in a differentiated, tailored understanding of health literacy in childhood and youth?

- What are the current challenges in the existing health literacy concepts for children and young people and what implications arise from these challenges?

- How can these considerations be transferred into a differentiated conceptual understanding?

2. Methods

3. Results

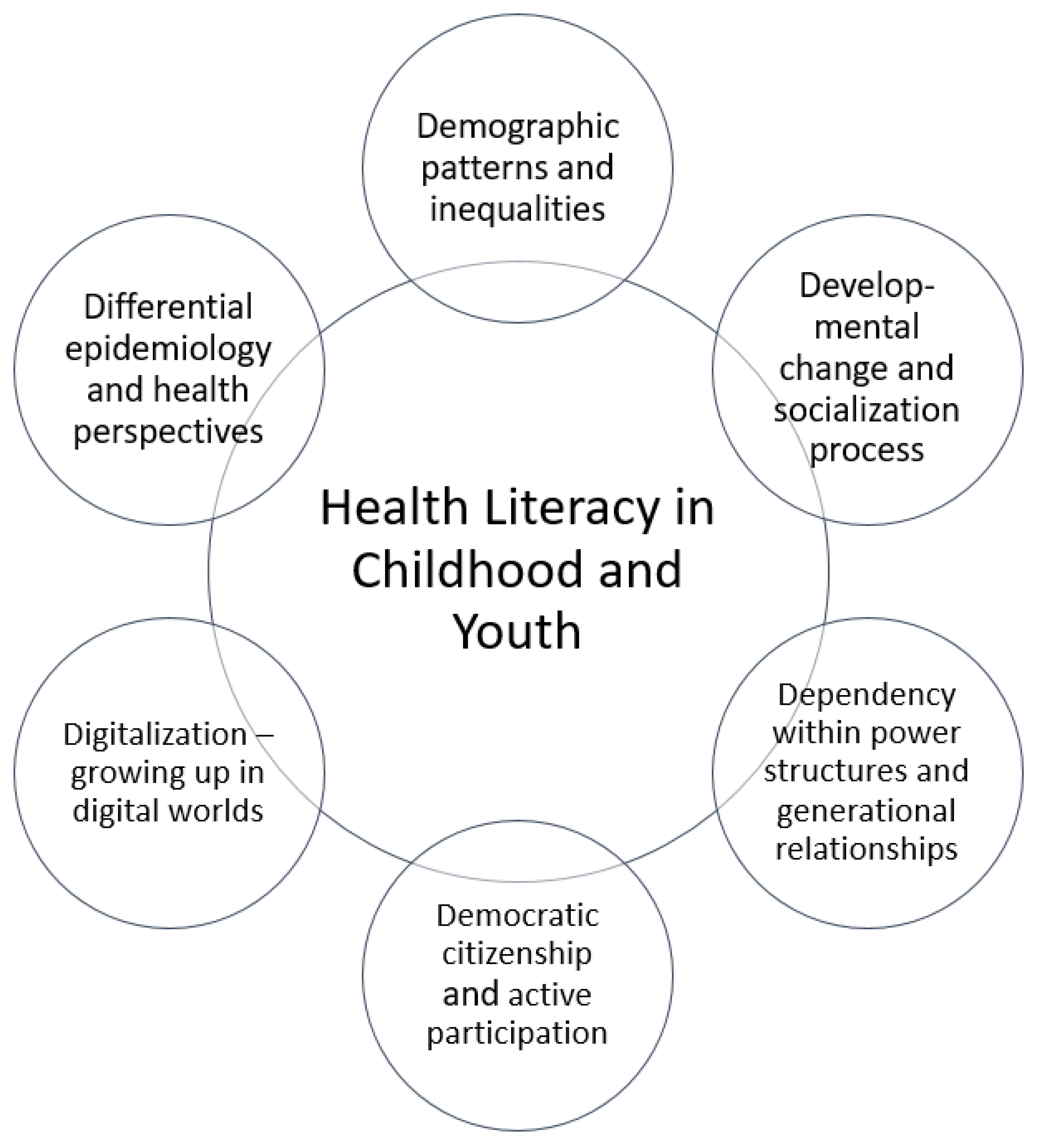

3.1. What Special Characteristics of Children and Young People are Relevant for Health Literacy?

3.2. Health Literacy of Children and Young People: Conceptual Analysis and Reflection

3.2.1. Content and Attributes

- Receiving or actively seeking access to relevant information for one’s health through various personal or medial channels (e.g., after encountering a situation, problem, or demand that requires more information);

- Cognitively processing, concentrating (attention) on, and comprehending the information in order to understand its content;

- Critically appraising the credibility, accuracy, and relevance of information as well as interacting with that information by constructing meaning from the information and relating it to one’s situation or reality; and

- Following up on this information through health-related actions and decision-making [11].

3.2.2. Antecedents and Contextual Interrelatedness

- The interpersonal context such as the parental socio-economic status, parental education level, and the home setting;

- Situational determinants such as the degree of social support as well as influences from family and peers, the school and community setting, and the media; and

- The distal social and cultural environment such as characteristics of the health and education system as well as political and social variables.

3.2.3. Subject of Interaction: Health Information/Message

3.2.4. Purpose and Expected Outcome

3.2.5. Target-Group Characteristics

3.3. Proposing and Discussing a Differentiated Understanding of Health Literacy

Health literacy of children and young people starts early in life and can be defined as a social and relational construct. It encompasses how health-related, multimodal information from various sources is accessed, understood, appraised, and communicated and used to inform decision-making in different situations in health (care) settings and contexts of everyday life, while taking into account social, cognitive, and legal dependence.As such, health literacy is observable in children’s and young people’s interaction and practices with health-related information, knowledge, messages in a given environment (so called ‘health literacy events or interactions’), while encountering and being promoted or hindered by social structures (in micro, meso, and macro contexts), power relationships, and societal demands.

1. Individual Health Literacy Assets: namely, the personal cognitive and habitual characteristics/attributes including the child’s independent knowledge along with abilities such as the ability to change, belief systems, cultural norms, and motivations.2. Social Health Literacy Assets: namely, the social and cultural resources one can access via present social support structures in the close social environment (family/peer/community context). This also points to the importance of the health literacy available to individuals and groups within their social environment and that, as such, is also part of the children’s health literacy.3. Situational Attributes of an Occasion in which Health Literacy is Relevant: namely, characteristics and demands of a given environment in which health literacy interactions—specifically the interaction with information or the health care setting—take place and that promote or hinder children in making use of individual and social health literacy assets. This, in turn, influences their agency and their real opportunities to practise and engage in health literacy interactions in their everyday lives.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characterizing Health Literacy from an Asset-Based Perspective

4.2. Considering Health Literacy as Being Socially Embedded and Distributed on Individual, Family, and Social Levels

Bike-riding requires the coordination of many working parts (gears, brakes, handle bars, and pedals). Each part has a unique purpose, but their contributions have little meaning apart from the whole. Similarly, we view an immigrant adolescent’s process of becoming ‘health literate’ as an evolving coordination of many working parts (e.g., reading skills, math skills, form-filling skills, linguistic choices, digital tools, or interactions that involve any of these skills and tools). The significance of these parts cannot be accurately understood when apart from the social, cultural, and historical context in which immigrant children are growing up.([57] page 4)

4.3. Recognizing that Health Literacy Starts Early in Life and Develops in Flexible Ways

4.4. Considering that Health-Related Information is Multimodal, Complex, and Power-Loaded

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fairbrother, H.; Curtis, P.; Goyder, E. Making health information meaningful: Children’s health literacy practices. SSM Popul. Health 2016, 2, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paakkari, L.; Paakkari, O. Health literacy as a learning outcome in schools. Health Educ. 2012, 112, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kickbusch, I.; Pelikan, J.M.; Apfel, F.; Tsouros, A.D. Health Literacy. The Solid Facts; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-92-890-00154. [Google Scholar]

- Inchley, J.; Currie, D. Growing Up Unequal. Gender and Socioeconomic Differences in Young People’s Health and Well-Being: Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from the 2013/2014 Survey; Inchley, J., Currie, D., Young, T., Samdal, O., Torsheim, T., Augustson, L., Mathison, F., Aleman-Diaz, A.Y., Molcho, M., Weber, M.W., et al., Eds.; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, M.; Hurrelmann, K. Life course influences on health and health inequalities: A socialisation perspective. Z. Soziologie Erzieh. Sozial. 2016, 36, 264–280. [Google Scholar]

- Simovska, V.; Bruun Jensen, B. Conceptualizing Participation: The Health of Children and Young People; WHO, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Velardo, S.; Drummond, M. Understanding parental health literacy and food related parenting practices. Health Sociol. Rev. 2013, 22, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzekowski, D.L.G. Considering children and health literacy: A theoretical approach. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, L.M.; Shaw, J.S.; Guez, G.; Baur, C.; Rudd, R. Health literacy and child health promotion: Implications for research, clinical care, and public policy. Pediatrics 2009, 124 (Suppl. 3), S306–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velardo, S.; Drummond, M. Emphasizing the child in child health literacy research. J. Child Health Care 2017, 21, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Bruland, D.; Schlupp, S.; Bollweg, T.M.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; Bond, E.; Sorensen, K.; Bitzer, E.-M.; et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloy-Weir, L.J.; Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Entwistle, V. A review of health literacy: Definitions, interpretations, and implications for policy initiatives. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okan, O.; Bröder, J.; Bauer, U.; Pinheiro, P. Health Literacy im Kindes- und Jugendalter—Eine explorierende Perspektive. In Health Literacy: Forschungsstand und Perspektiven; Schaeffer, D., Pelikan, J., Eds.; Hogrefe: Bern, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bröder, J.; Carvalho, G.S. Health literacy of children and adolescents: Conceptual approaches and developmental considerations. In International Handbook of Health Literacy Research, Practice and Policy across the Life-Span; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1447344513. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, B.L. Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: The evolutionary cycle. J. Adv. Nurs. 1989, 14, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, B.L. Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Rogers, R., Knafl, K.A., Eds.; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y. Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Schlupp, S.; Pinheiro, P. Advancing perspectives on health literacy in childhood and youth. Health Promot. Int. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Prout, A. (Eds.) Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood. Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood, Classic ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-315-74500-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, R.L.; Yin, H.S.; Mulvaney, S.; Co, J.P.T.; Homer, C.; Lannon, C. Health literacy and quality: Focus on chronic illness care and patient safety. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S315–S326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanen, L.; Brooker, L.; Mayall, B. Childhood with Bourdieu; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 1137384735. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, P. Gesundheit durch Bedürfnisbefriedigung; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2006; ISBN 9783801720292. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. The Health Gap. The Challenge of an Unequal World, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury Press, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781632860781. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Children at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Children_at_risk_of_poverty_or_social_exclusion (accessed on 24 October 2018).

- Marmot, M.G.; Wilkinson, R. (Eds.) The Solid Facts. Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; ISBN 9289013710. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, N. Children, Youth and Development, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 0-203-82940-9. [Google Scholar]

- Oerter, R.; Montada, L. Entwicklungspsychologie. Lehrbuch, 6th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; ISBN 9783621276078. [Google Scholar]

- Havinghurst, R.J. History of Developmental Psychology: Socialization and Personality Development through the Life Span. In Life-Span Developmental Psychology: Personality and Socialization; Baltes, P.B., Schaie, K.W., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Burlington, NJ, USA, 1973; pp. 3–24, (reprint 2013); ISBN 9780120771509. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler-Niederberger, D. Introduction. Curr. Sociol. 2010, 58, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayall, B. Generational Relations at Family Level. In The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies; Qvortrup, J., Corsaro, W.A., Honig, M.-S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 175–187. ISBN 978-0-230-27468-6. [Google Scholar]

- Oswell, D. Re-aligning children’s agency and re-socialising children in childhood studies. In Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New Perspectives in Childhood Studies; Esser, F., Baader, M.S., Betz, T., Hungerland, B., Eds.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 19–33. ISBN 978-1-315-72224-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, J.S.; Touloumtzis, C.; White, M.T.; Colbert, J.A.; Gooding, H.C. Adolescent and Young Adult Use of Social Media for Health and Its Implications. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, C.K.; Bridges, S.M.; Srinivasan, D.P.; Cheng, B.S. Social media in adolescent health literacy education: A pilot study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015, 4, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, R.; Thomas, Y. Emerging shifts in learning paradigms - from millenials to the digital natives. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2016, 5, 3616–3618. [Google Scholar]

- Wharf Higgins, J.; Begoray, D. Exploring the Borderlands between Media and Health: Conceptualizing ‘Critical Media Health Literacy’. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2012, 4, 136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chuen, E.M.; Michael, E.; Teck, T.B. The Role of Media Socialization Agents in Increasing Obesity Health Literacy among Malaysian Youth. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2016, 32, 691–714. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, J.M. Health literacy: A concept/dimensional analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2008, 10, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.T.; Shapiro, R.M.; Gillaspy, M.L. Top Down versus Bottom Up: The Social Construction of the Health Literacy Movement. Libr. Q. 2012, 82, 429–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Reber, B.H.; Lariscy, R.W. Roles of interpersonal and media socialization agents in adolescent self-reported health literacy: A health socialization perspective. Health Educ. Res. 2011, 26, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickbusch, I.; Wait, S.; Maag, D.; Banks, I. Navigating health: The role of health literacy. In Alliance for Health and the Future; International Longevity Centre: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baheiraei, A.; Khoori, E.; Foroushani, A.R.; Ahmadi, F.; Ybarra, M.L. What sources do adolescents turn to for information about their health concerns? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2014, 26, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettel, G.; Nathanson, I.; Ettel, D.; Wilson, C.; Meola, P. How Do Adolescents Access Health Information? And Do They Ask Their Physicians? Perm. J. 2012, 16, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kress, G.R. Multimodality. A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0415320610. [Google Scholar]

- Gossen, T.; Nürnberger, A. Specifics of information retrieval for young users: A survey. Inf. Process. Manag. 2013, 49, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, K.H. What Is Literacy?—A Critical Overview of Sociocultural Perspectives. J. Lang. Lit. Educ. 2012, 8, 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards. National Health Education Standards: Achieving Health Literacy. American Cancer Society: New York, NY, USA. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED386418.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2019).

- Wharf Higgins, J.; Begoray, D.; MacDonald, M. A social ecological conceptual framework for understanding adolescent health literacy in the health education classroom. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 44, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackert, M.; Champlin, S.; Su, Z.; Guadagno, M. The many health literacies: Advancing research or fragmentation? Health Commun. 2015, 30, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.; Wood, F.; Davies, M.; Edwards, A. ‘Distributed health literacy’: Longitudinal qualitative analysis of the roles of health literacy mediators and social networks of people living with a long-term health condition. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D. Directions for literacy research: Analysing language and social practices in a textually mediated world. Lang. Educ. 2001, 15, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I. Consultation with children in hospital: Children, parents’ and nurses’ perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model. Promot. Educ. 2007, 14, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, L.; Kendall, S.; Wills, W. An asset-based approach: An alternative health promotion strategy? Community Pract. 2012, 85, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.G.; Gorukanti, A.L.; Jurkunas, L.M.; Handley, M.A. The Health Literacy of U.S. Immigrant Adolescents: A Neglected Research Priority in a Changing World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase 1 | Identifying and choosing the concept for analysis and mapping the selected data sources |

| Phase 2 | Extensively reading and categorizing the selected data |

| Phase 3 | Identifying and naming the dimensions and components of a concept |

| Phase 4 | Deconstructing and categorizing the concept’s attributes, characteristics, and assumptions |

| Phase 5 | Integrating the components |

| Phase 6 | Grouping, synthesizing, and resynthesizing the dimensions |

| Phase 7 | Validating the results |

| Phase 8 | Identifying hypotheses and implications for future research and development |

| ‘6 D’s’ | Description |

|---|---|

| Differential epidemiology and health perspectives | ‘Health’ or ‘well-being’ and ‘disease’ or ‘illness’ are culturally loaded concepts that are open to being interpreted and constructed socially. Hence, their meaning may differ within and between individuals, age groups, cultures, and professions (the ‘expert’ and the ‘lay person’) [22]. Children and young people understand and attribute meaning to the concept of health, of being healthy, or of being well by drawing on their personal embodied experience and their interpretation or uptake of articulated health-related beliefs and attitudes in their proximal social surroundings [1]. Although children and young people partly suffer from similar diseases and are exposed to similar health risk profiles as adults, some disease and health risks are highly age- or development-specific and are related to an increased vulnerability for exposure [4]. |

| Demographic patterns and inequalities | Children and young people are especially vulnerable to social and health inequalities, because their health is influenced by a multitude of complex and interrelated factors in their proximal and distant social environment [4,23]. They are the age group with the highest poverty risk according to socio-demographic characteristics [24]. Factors such as low family socio-economic status, poor living conditions, poor access to higher education and social support structures, as well as having a migration background are associated with an increased risk of educational disadvantage; lack of skills, knowledge, and competencies; or even psychosocial developmental disabilities [4]. Children and young people exposed to these factors face a two times higher risk of obesity and rate their subjectively perceived health status and quality of life below the age group’s average [24,25]. |

| Developmental change and socialization process | Childhood and youth are life phases in which essential biological, cognitive, psychological, emotional, and social development processes take place [26,27]. Every developmental phase is accompanied by specific developmental features, typical challenges, and social expectations e.g., [28]. Children and young people have to handle these expectations in order to shape their development process beneficially, and this advances their maturity and autonomy [26,27]. Apart from cognitive development aspects, namely the skills and competencies children should be capable of mastering and employing in the context of health literacy at a certain age or developmental stage, it is crucial to also recognize the sociological and psychosocial development processes that are taking place [14]. |

| Dependency within power structures and inter-generational relationships | Whereas children and young people rely, to the extent they are dependent, on their parents’ assistance, competence, economic resources, and social support, they, at the same time, actively engage in and form their own social world/realities [21,29]. Intergenerational power relations and conflicts are evident when children interact with adult society, and this reflects the unequal distribution of power between children and adults [30]. Characteristics of generational order and social position are negotiated on a daily basis within peer groups as well as between children, adolescents, and adults [21]. |

| Democratic citizenship and active participation | Children and young people have a right to be informed, to participate actively in their own health (decision-making), to access health information, and to have this information presented to them in understandable and appropriate manners [1,13].They are embodied beings and social actors within their own right who encounter and engage in health information and health-relevant situations on a daily basis [6].Children and young people’s agency can be characterized as contingent on the responsiveness of and the opportunities available within the networks of actors and the structure of the social [31]. |

| Digitization/Digital worlds of growing up | Many children and young people grow up in highly digitized and media-saturated settings [32,33]. Some refer to children and young people as ‘digital natives’, implying that children ‘naturally’ learn and become socialized with digital media formats because digital media are an integral component of their daily lives [34]. Because they encounter and access health information in various or even multiple digital forms and formats, considering the opportunities and challenges in digital and media settings with their various multimodal formats is crucial for understanding children’s and young people’s health literacy and their health information seeking [35,36]. |

| Description of Findings | Prominent Argumentation Lines Identified in the Conceptual Analysis | Implications and Challenges Arising from the Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Two major perspectives on health literacy during childhood and youth: |

| |

| (a) Action- and output-focused perspectives |

| |

| (b) Skills-focused perspectives |

| |

| Description of Findings | Prominent Argumentation Lines Identified in the Conceptual Analysis | Implications and Challenges Arising from the Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Consideration of contextual influences and the relational character of health literacy for children and young people remains shallow |

|

|

| Description of Findings | Prominent Argumentation Lines Identified in the Conceptual Analysis | Implications and Challenges Arising from the Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Health literacy is prominently defined as being centred around information or messages |

|

|

| Description of Findings | Prominent Argumentation Lines Identified in the Conceptual Analysis | Implications and Challenges Arising from the Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential effect relationship is proposed |

|

|

| Description of Findings | Prominent Argumentation Lines Identified in the Conceptual Analysis | Implications and Challenges Arising from the Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Target-group characteristics in available concepts considered mainly in terms of cognitive development theories and deficit-oriented approaches |

|

|

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bollweg, T.M.; Bruland, D.; Pinheiro, P.; Bauer, U. Child and Youth Health Literacy: A Conceptual Analysis and Proposed Target-Group-Centred Definition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183417

Bröder J, Okan O, Bollweg TM, Bruland D, Pinheiro P, Bauer U. Child and Youth Health Literacy: A Conceptual Analysis and Proposed Target-Group-Centred Definition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(18):3417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183417

Chicago/Turabian StyleBröder, Janine, Orkan Okan, Torsten M. Bollweg, Dirk Bruland, Paulo Pinheiro, and Ullrich Bauer. 2019. "Child and Youth Health Literacy: A Conceptual Analysis and Proposed Target-Group-Centred Definition" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 18: 3417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183417

APA StyleBröder, J., Okan, O., Bollweg, T. M., Bruland, D., Pinheiro, P., & Bauer, U. (2019). Child and Youth Health Literacy: A Conceptual Analysis and Proposed Target-Group-Centred Definition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(18), 3417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183417