“Let’s Talk About It”: The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure on Complicated Grief over Time among Suicide Survivors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Disclosure

1.2. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

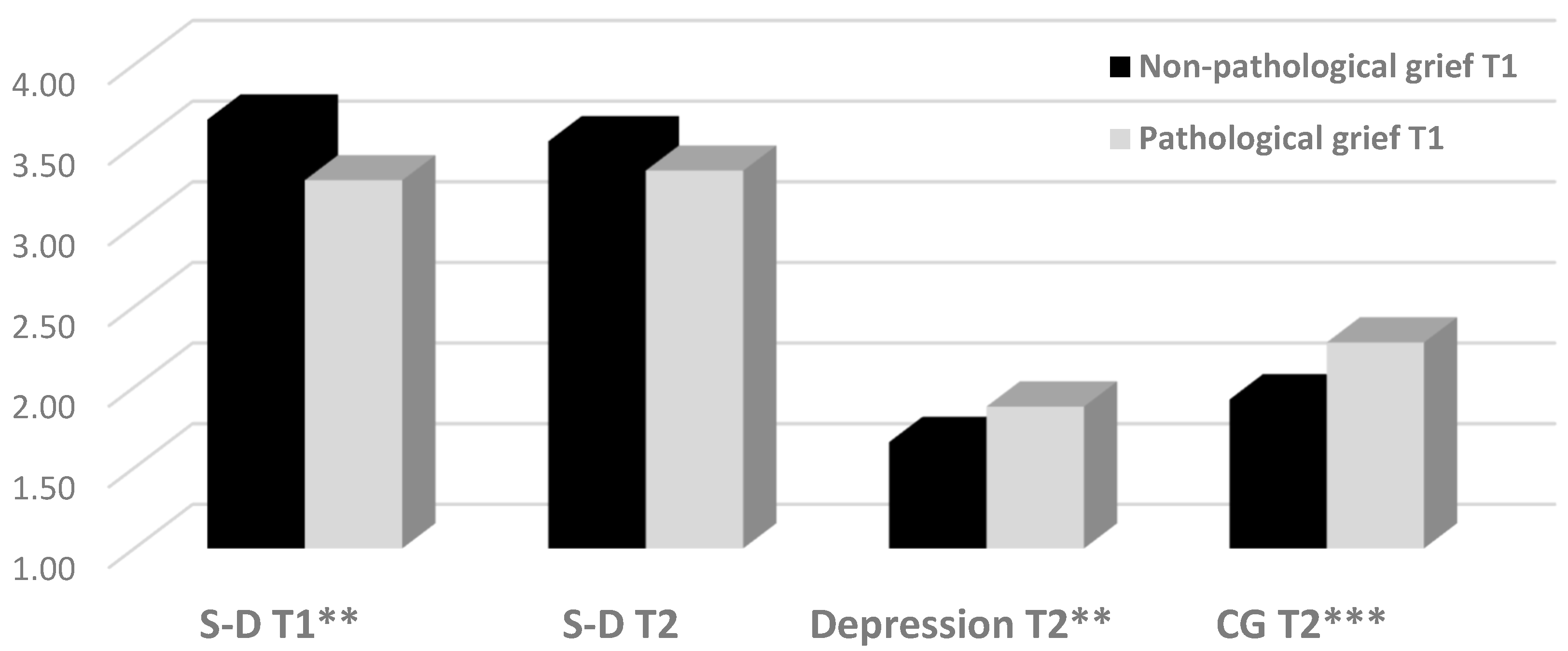

3.1. Differences between Pathological and Non-Pathological CG

3.2. Differences in CG as a Function of S-D Level

3.3. The Contribution of S-D to the Trajectory of CG Among SUSs

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of S-D as Protective Factor Against CG among SUSs

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cerel, J.; Brown, M.M.; Maple, M.; Singleton, M.; van de Venne, J.; Moore, M.; Flaherty, C. How many people are exposed to suicide? Not six. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerel, J. Connecting to the continuum of survivorship. In Proceedings of the National Suicide Prevention Conference: Connecting Culture, Context and Capabilities, Canberra, Australia, 24–27 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maple, M.; Cerel, J.; Sanford, R.; Pearce, T.; Jordan, J. Is exposure to suicide beyond kin associated with risk for suicidal behavior? A systematic review of the evidence. Suicide Life Threat. Behav 2017, 47, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shneidman, E.S. Suicide as Psychache: A Clinical Approach to Self-Destructive Behavior; Jason Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Galea, S.; Bucciarelli, A.; Vlahov, D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerel, J.; McIntosh, J.L.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Maple, M.; Marshall, D. The continuum of “survivorship”: Definitional issues in the aftermath of suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2014, 44, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, I.T.; Iglewicz, A.; Glorioso, D.; Lanouette, N.; Seay, K.; Ilapakurti, M.; Zisook, S. Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, M.J.; Siegel, B.; Holen, A.; Bonanno, G.A.; Milbrath, C.; Stinson, C.H. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Focus 2003, 1, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannen, P.K.; Wolfe, J.; Prigerson, H.G.; Onelov, E.; Kreicbergs, U.C. Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: Impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5870–5876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, N.J.; Simon, N.M.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Shear, M.K.; Skritskaya, N.; Zisook, S. Relationship Between Complicated Grief and Depression: Relevance, Etiological Mechanisms, and Implications. In Neurobiology of Depression; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Prigerson, H.G.; Mortimer, M.K. Complicated grief and suicidal ideation in adult survivors of suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2005, 35, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersting, A.; Brähler, E.; Glaesmer, H.; Wagner, B. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 131, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, W.; Burnett, P.; Raphael, B.; Martinek, N. The bereavement response: A cluster analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 169, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Horowitz, M.J.; Jacobs, S.C.; Parkes, C.M.; Aslan, M.; Goodkin, K.; Raphael, B.; Marwit, S.J.; Wortman, C.; Neimeyer, R.A.; et al. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.R. Bereavement after suicide. Psychiatr. Ann. 2008, 38, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Lev-Ari, L. Is there anybody out there? Attachment style and interpersonal facilitators as protective factors against complicated grief among suicide-loss survivors. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shear, K.; Skritskaya, N.; Wang, Y. Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Prigerson, H.G.; Mortimer-Stephens, M. Complicated grief in survivors of suicide. Crisis 2004, 25, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveen, C.A.; Walby, F.A. Suicide survivors’ mental health and grief reactions: A systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, E.A.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Aoun, S.M.; Monterosso, L.; Halkett, G.K.; Davies, A. Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 673–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourard, S.M. Self-Disclosure: An Experimental Analysis of the Transparent Self; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Gvion, Y.; Horesh, N.; Fischel, T.; Treves, I.; Or, E.; Stein-Reisner, O.; Weiser, M.; David, H.S.; Apter, A. Mental pain, communication difficulties, and medically serious suicide attempts: A case-control study. Arch. Suicide Res. 2014, 18, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Joseph, S.; Das Nair, R. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of posttraumatic growth in adults bereaved by suicide. J. Loss Trauma 2011, 16, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigelman, W.; Cerel, J.; Sanford, R. Disclosure in traumatic deaths as correlates of differential mental health outcomes. Death Stud. 2017, 42, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oexle, N.; Feigelman, W.; Sheehan, L. Perceived suicide stigma, secrecy about suicide loss and mental health outcomes. Death Stud. 2018, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.R.; McMenamy, J. Interventions for suicide survivors: A review of the literature. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004, 34, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W. Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychol. Sci. 1997, 8, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y. Stress-related growth among suicide survivors: The role of interpersonal and cognitive factors. Arch. Suicide Res. 2015, 19, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi-Belz, Y. Relationship with the deceased as facilitator of posttraumatic growth among suicide-loss survivors. Death Stud. 2017, 41, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Lev-Ari, L. Attachment styles and posttraumatic growth among suicide-loss survivors: The mediating role of interpersonal factors. Crisis 2018, 40, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi-Belz, Y. With a little help from my friends: A follow-up study on the contribution of interpersonal characteristics to posttraumatic growth among suicide-loss survivors. Psychol. Trauma 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerel, J.; Maple, M.; De Venne, J.V.; Moore, M.; Flaherty, C.; Brown, M. Exposure to suicide in the community: Prevalence and correlates in one US state. Public Health Rep. 2016, 131, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, J.H.; Hessling, R.M. Measuring the tendency to conceal versus disclose psychological distress. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 20, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Jacobs, S. Traumatic grief as a distinct disorder: A rationale, consensus criteria, and a preliminary empirical test. In Handbook of Bereavement Research; Stroebe, M.S., Hansson, R.O., Stroebe, W., Schut, H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 613–645. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Bierhals, A.J.; Newsom, J.T.; Fasiczka, A.; Frank, E.; Doman, J.; Miller, M. Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995, 59, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnider, K.R.; Elhai, J.D.; Gray, M.J. Coping style use predicts posttraumatic stress and complicated grief symptom severity among college students reporting a traumatic loss. J. Couns. Psychol. 2007, 54, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, A.E.; Prigerson, H.G. Suicidality and bereavement: Complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2004, 34, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Shear, M.K.; Jacobs, S.C.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Maciejewski, P.K.; Davidson, J.R.T.; Rosenheck, R.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Wortman, C.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; et al. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief: A preliminary empirical test. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1999, 174, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.; Lasgaard, M.; Shevlin, M.; Guldin, M.B. A confirmatory factor analysis of combined models of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Inventory of Complicated Grief-Revised: Are we measuring complicated grief or posttraumatic stress? J. Anxiety Disord. 2010, 24, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1993, 154, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Sheehan, L.; Al-Khouja, M.A.; Lewy, S.; Major, D.R.; Mead, J.; Redmon, M.; Rubey, C.T.; Weber, S. Insight into the stigma of suicide loss survivors: Factor analyses of family stereotypes, prejudices, and discriminations. Arch. Suicide Res. 2018, 22, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, S.; Erbuto, D.; Andriessen, K.; Milelli, M.; Innamorati, M.; Lester, D.; Sampogna, G.; Fiorillo, A.; Pompili, M. Depression, hopelessness, and complicated grief in survivors of suicide. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, J.M.; Pennebaker, J.W.; Arigo, D. What are the health effects of disclosure? Handbook of Health Psychology; Revenson, T.A., Singer, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Trakhtenbrot, R.; Gvion, Y.; Levi-Belz, Y.; Horesh, N.; Fischel, T.; Weiser, M.; Treves, I.; Apter, A. Predictive value of psychological characteristics and suicide history on medical lethality of suicide attempts: A follow-up study of hospitalized patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 199, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gvion, Y.; Levi-Belz, Y. Serious suicide attempts: Systematic review of psychological risk factors. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigelman, W.; Sanford, R.L.; Cerel, J. Do primary care physicians help the bereaved with their suicide losses: Loss survivor perceptions of helpfulness from physicians. Omega (Westport) 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, J.H.; Garrison, A.M. Emotional self-disclosure and emotional avoidance: Relations with symptoms of depression and anxiety. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Y.; Horesh, N.; Fischel, T.; Treves, I.; Or, E.; Apter, A. Mental pain and its communication in medically serious suicide attempts: An “impossible situation”. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 111, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Hogan, N.S. Handbook of Bereavement Research: Consequences, Coping, and Care; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scrignaro, M.; Barni, S.; Magrin, M.E. The combined contribution of social support and coping strategies in predicting post-traumatic growth: A longitudinal study on cancer patients. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.J.; Heimberg, R.G. Effects of writing about rape: Evaluating Pennebaker’s paradigm with a severe trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 2001, 14, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, S.H.; Range, L.M. Writing projects: Lessening undergraduates’ unique suicidal bereavement. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2000, 30, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Keough, K.A. Revealing, organizing, and reorganizing the self in response to stress and emotion. In Self, Social Identity and Physical Health: Interdisciplinary Exploration; Contrada, R.J., Ashmore, R.D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Zech, E.; Rimé, B. Disclosing and sharing emotion: Psychological, social, and health consequences. In Handbook of Bereavement Research: Consequences, Coping, and Care; Stroebe, M.S., Hansson, R.O., Stroebe, W., Schut, H., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 517–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, S.J.; Cohen, S.R.; Wortman, C.B.; Waymerit, H. Social constraints, intrusive thoughts, and depressive symptoms among bereaved mothers. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattaroli, J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 823–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, W.B. I have to talk to somebody: A fever model of disclosure. In Self-Disclosure: Theory, Research, and Therapy; Derlega, V.J., Berg, J.H., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Farber, B.A. Self-Disclosure in Psychotherapy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, W.; Schut, H.; Stroebe, M.S. Grief work, disclosure and counseling: Do they help the bereaved? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, C.H.; Batten, P.G.; Parish, E.A. Loneliness and patterns of self-disclosure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 4, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y. To share or not to share? The contribution of self-disclosure to stress-related growth among suicide survivors. Death Stud. 2016, 40, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemenover, S.H. The good, the bad, and the healthy: Impacts of emotional disclosure of trauma on resilient self-concept and psychological distress. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvinar, J.G. Do suicide survivors suffer social stigma: A review of the literature. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2005, 41, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choenarom, C.; Williams, R.A.; Hagerty, B.M. The role of sense of belonging and social support on stress and depression in individuals with depression. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2005, 19, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, J.C.; Weissman, M.M. Interpersonal psychotherapy: Principles and applications. World Psychiatry 2004, 3, 136–139. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levi-Belz, Y.; Lev-Ari, L. “Let’s Talk About It”: The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure on Complicated Grief over Time among Suicide Survivors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193740

Levi-Belz Y, Lev-Ari L. “Let’s Talk About It”: The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure on Complicated Grief over Time among Suicide Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(19):3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193740

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevi-Belz, Yossi, and Lilac Lev-Ari. 2019. "“Let’s Talk About It”: The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure on Complicated Grief over Time among Suicide Survivors" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 19: 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193740

APA StyleLevi-Belz, Y., & Lev-Ari, L. (2019). “Let’s Talk About It”: The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure on Complicated Grief over Time among Suicide Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193740