3.1. Graph Model and Traditional Option Prioritization Approach

A conflict can be expressed by a graph model

, where

N,

S, and

A represent the set of DMs, states, and oriented arcs, respectively, and

refers to a binary preference relationship. For instance,

means that state

is more preferred to state

by DM

i, while

indicates that the two states are equally preferred by DM

i. There are three preference elicitation approaches within the framework of the GMCR: direct ranking, option weighting, and option prioritization [

17,

18]. More specifically, the first approach can be easily used in smaller conflict models with limited states for directly ranking states according to a DM’s value-based system. In the second method, the ordering of states is determined according to their total weights which can be calculated by using each option’s weight. However, some preference ordering over states cannot obtained by using this approach. In a given conflict, if the number of options is

a, then the number of states can be written as 2

a since each option can be chosen or not. The option prioritization is from the option level instead of the state level, which can significantly improve the computational efficiency of preference ranking, especially for large-scale conflicts. When analyzing the preference of DMs in a dispute, we only need to acquire a set of option statements for each DM which are ranked from most to least important in a hierarchical order. Therefore, the option prioritization approach is the most effective and convenient preference ranking method. An option statement consists of numbered options and logical operators.

In a given conflict, DM

i’s preference over states can be intuitively expressed by a set of option statements

ordered by priority, where

k is the total number of statements, and the former statement is more important than the latter one. Each option statement

takes a truth value at state

, denoted by

. Specifically,

if the statement

is true (T) at state

s; otherwise,

. Let

be the incremental score of

at state

s, where

Then, the total score of state

s can be determined by

All of the states can be ranked from most to least preferred according to their total scores, in which a state with a higher score is more preferred to a state with a lower score by DM i, and states with the same score are equally preferred. Therefore, each DM’s preference can be determined using the option prioritization approach. In many real-world conflicts, however, the most and least preferred states which can be easily and directly obtained may be not consistent with the results by using the option prioritization technique. Moreover, the option statements given by conflict analysts may be different or inconsistent because of subjective judgments. Hence, a novel preference ranking approach is purposefully developed below.

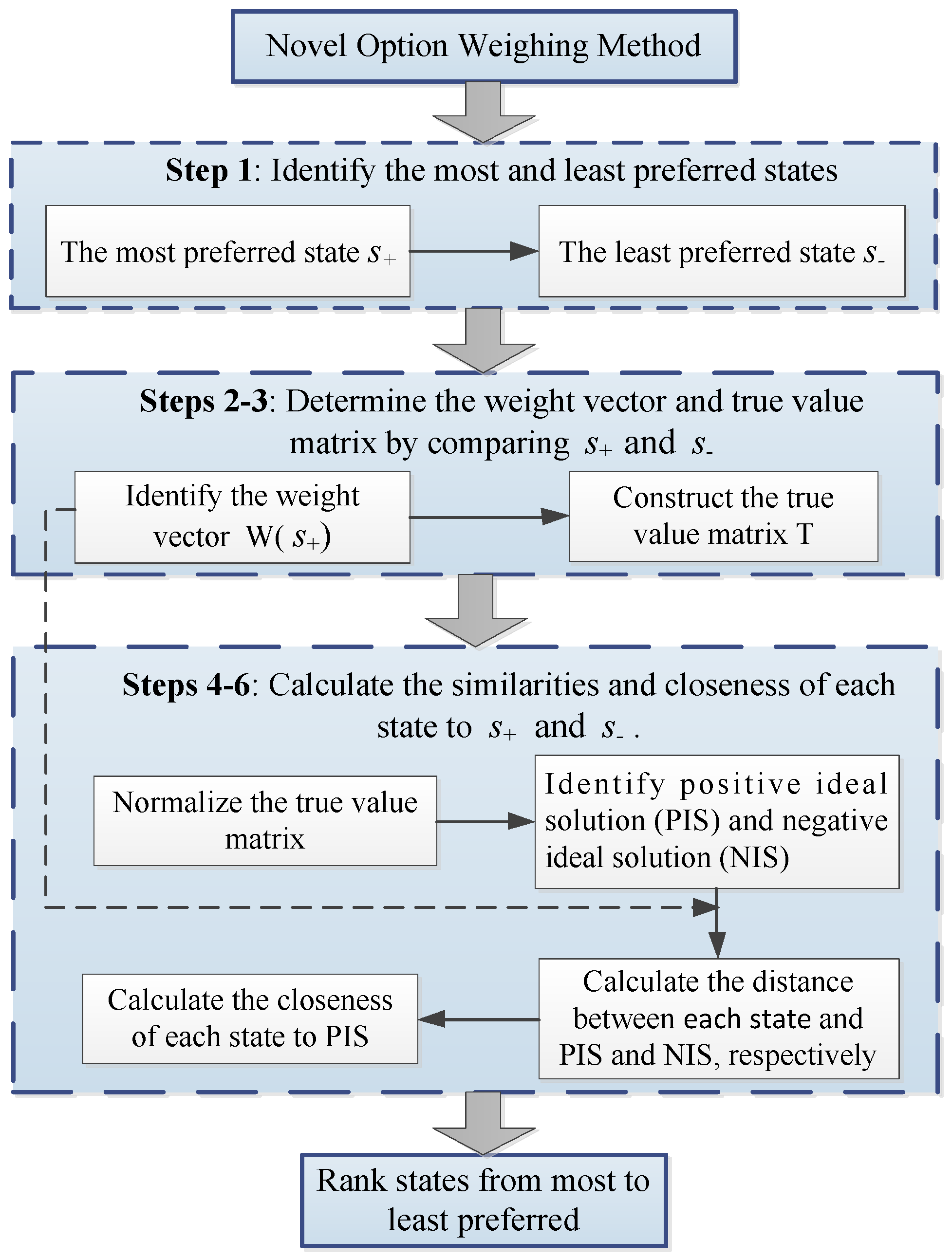

3.2. A Novel Option Weighing Technique for Preference Ranking

In a given conflict, as mentioned above, the most and least preferred states can be easily and intuitively identified by a focal DM, which indicates that it is not necessary to obtain them by using option prioritization. Moreover, the remaining states can be ranked from most to least preferred according to their similarities and closeness to the best and worst states, which is similar to the technique for order preference by similarity to an ideal solution (TOPSIS) [

37,

38]. In this research, a novel option weighing approach is proposed within the framework of GMCR for more efficiently eliciting the preference information of a DM. To begin with, some symbols which are used later, as well as their corresponding explanations, are presented in

Table 1.

Let

be the set of options in a given conflict. A strategy for a DM is a combination of its options, and a state is an outcome when each DM’s strategy is determined, which can be represented by a

k-dimensional column vector

, where

Let the set of states be . The procedure for determining a DM’s preference by using the novel option weighing approach is designed as follows:

Step 1: Identify the most and least preferred states for the DM denoted by and , respectively.

Step 2: Determine the weight vector of all elements in , in which is the weight of .

- (1)

Rank in order of priority from most to least important, where

if and , then , and

if , then and are evaluated according to their importance to the focal DM.

- (2)

Assign the numerical scores for each weight according to their orders in (1), in which the lth biggest weight is 2k − l.

Note that the weight vector represents the importance of each element in the most preferred state . Comparing the most and least preferred states, one can find that there are two types of elements in : one is the same as the corresponding element in ; and the other is different from the corresponding element in . Note that the elements in the second type should be more important than those in the first type. Moreover, the elements in each type are ranked in terms of their importance to the focal DM.

Step 3: Calculate the true value matrix by comparing each state

with the best state

written by

where the row represents

, the column refers to states from

to

, and

Step 4: Normalize the true value matrix

T using the below equation which is similar to that in TOPSIS method. The normalized matrix can be written by

, in which

Then, the optimal and worst solution solutions can be determined as described below.

The positive ideal solution (PIS) is

Note that some normalized true values in the row of

could be the same as those in the row of

. Unlike the traditional TOPSIS method, the negative ideal solution (NIS) in the novel option weighing approach is denoted by

where

j is the row of the least preferred state

.

Step 5: Calculate the distance between every state and the optimal and worst states as presented below.

The distance between

and

is

The distance between

and

is

Step 6: Calculate the closeness between every state

and the positive ideal solution

by using the following equation:

Step 7: Determine the DM’s preference over states according to the values of , in which a state with a higher value is more preferred to another state with a lower value. For example, if , then state is more preferred to state (), and, if , then states and are equally preferred ().

The detailed procedure for calculating a DM’s preference over states by using the novel option weighing method is depicted in

Figure 1. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the most and least preferred states should be firstly identified. By comparing the similarities and differences between the best and worst states, one can then construct the weight vector and true value matrix. Subsequently, the similarities and closeness of each state to the best and worst states should be analyzed, which is similar to the TOPSIS method. Finally, states can be ranked from most to least preferred according to their values of closeness to the optimal and worst solutions.