The Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions: Focusing on Chinese Tourist Shopping at a Duty Free

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Travelers’ Experiences at a Duty Free Shop

2.2. Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions

2.3. Brand Attitude and Brand Preference

2.4. Word-of-Mouth

2.5. Relationships among Study Variables

2.6. Proposed Model

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Demographic Characteristics

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Disagree→Neutral→Agree | |||||

| Pragmatic Experience | |||||

| Worthwhile | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Useful | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Valuable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Relevant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Hedonic experience | |||||

| Pleasing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Exciting | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Deeply engrossing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Enjoyable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Sociability experience | |||||

| Friendly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Personal | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Polite | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Inviting | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Usability experience | |||||

| Not tiring | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Not stressful | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Not confusing | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Consistent | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Well-being perceptions | |||||

| This duty-free shop played an important role in my well-being. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| This duty-free shop met my overall well-being needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| This duty-free shop played an important role in enhancing my quality of life. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Brand attitude How would you characterize your attitude toward the duty-free shop? I think my attitude toward the duty-free shop is… | |||||

| Unfavorable—Favorable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Dislike—Like | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Bad—Good | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Unpleasant—Pleasant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Poor quality—High quality | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Unsatisfactory—Satisfactory | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Brand preference | |||||

| When I want to shop, I consider this duty-free shop a viable choice very often. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| This duty-free shop meets my shopping needs better than other comparable duty-free shops | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am interested in this duty-free shop more than in other comparable duty-free shops | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Word-of-mouth | |||||

| I said positive things about this duty-free shop to others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I recommended this duty-free shop to others. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I encouraged others to visit this duty-free shop. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- Jin, H.; Moscardo, G.; Murphy, L. Exploring Chinese Outbound Tourist Shopping: A Social Practice Framework. J. Travel Res. 2019, 59, 0047287519826303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Daily. China Still No. 1 Outbound Tourism Market. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201903/13/WS5c88f6aca3106c65c34ee74c.html (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Korea Tourism Organization “Tourism Statistics”. Available online: https://kto.visitkorea.or.kr/eng/tourismStatics/keyFacts/KoreaMonthlyStatistics.kto (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Financial Times. China Begins to Lift Ban on Group Tours to South Korea. 2018. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/1067ceb6-aaa0-11e8-94bd-cba20d67390c (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Korea Times. Japanese Tourists Come to Korea for Food, Chinese for Shopping. 2019. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2019/06/281_270503.html (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Zeng, S.; Chiu, W.; Lee, C.W.; Kang, H.-W.; Park, C. South Korea’s destination image: Comparing perceptions of film and nonfilm Chinese tourists. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-F. Passengers’ shopping motivations and commercial activities at airports—The moderating effects of time pressure and impulse buying tendency. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; McGehee, N.G. Shopping behavior of Chinese tourists visiting the United States: Letting the shoppers do the talking. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daxue Consulting. What do Chinese Consumers Think of Duty Free Shops? Available online: https://daxueconsulting.com/chinese-consumers-duty-free-shopping/ (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Reuters. Chinese Shoppers in South Korea Shun Luxury for Local Brands. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-china-tourists/chinese-shoppers-in-south-korea-shun-luxury-for-local-brands-idUSKCN0VE02D (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- M1nd-Set. Top 15 Nationalities in DF Sales Market Share and Traffic Evolution. Available online: https://www.m1nd-set.com/products-and-services/#global-travel-retail-shopper-segmentation (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Maeil Business News Korea. Korean Duty-Free Shops Post Near $10 bn Sales H1 Thanks to Big Chinese Spenders. 2019. Available online: https://pulsenews.co.kr/view.php?year=2019&no=531787 (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Chen, C.-C.; Huang, W.-J.; Petrick, J.F. Holiday recovery experiences, tourism satisfaction and life satisfaction–Is there a relationship? Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.Y.; Mitchell, V.-W. A mechanism model of the effect of hedonic product consumption on well-being. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, R.T.; Guevarra, D.A. Buying happiness: Differential consumption experiences for material and experiential purchases. Adv. Psychol. Res. 2013, 98, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Kruger, P.S.; Lee, D.-J.; Yu, G.B. How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudders, L.; Pandelaere, M. The silver lining of materialism: The impact of luxury consumption on subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, D. The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Zeng, S.; Cheng, P.S.-T. The influence of destination image and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: A case study of Chinese tourists in Korea. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Ko, T.G. A cross-cultural study of perceptions of medical tourism among Chinese, Japanese and Korean tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Cai, L.A.; Jung, K. A profile of the Chinese casino vacationer to South Korea. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, H.; Yong, S.; Ko, E. Pop culture, destination images, and visit intentions: Theory and research on travel motivations of Chinese and Russian tourists. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas, J.P. Feeling and Thinking: The Role of Affect in Social Cognition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdare, S.; Jain, R. Measuring retail customer experience. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Levy, M.; Kumar, V. Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, P.P.; Maklan, S. Towards a better measure of customer experience. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 55, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Magnini, V.P.; Singal, M. The effects of customers’ perceptions of brand personality in casual theme restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Thorpe, D.I.; Rentz, J.O. A measure of service quality for retail stores: Scale development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Atkins, K.; Kim, Y.-K. Smart shopping: Conceptualization and measurement. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, F.; Clark, M.; Wilson, H. Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 846–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Romero, C.; Constantinides, E.; Brünink, L.A. Co-creation: Customer integration in social media based product and service development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, P.; Watt, J.H. Managing customer experiences in online product communities. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, T.; Fueller, J.; Matzler, K.; Stieger, D. Co-creation in virtual worlds: The design of the user experience. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Salimi, M.; Haque, A. The impact of online customer experience (OCE) on service quality in Malaysia. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 21, 1621–1631. [Google Scholar]

- Zafir, H.O. The Impact of Customers Experience Quality on Brand Loyalty: A Study of Health and Diet Online Communities. Ph.D. Thesis, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nambisan, P. Social Media Experience: Impact on employee mental well-being. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2017; p. 14650. [Google Scholar]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Park, J.-W. The decision-making processes of duty-free shop users using a goal directed behavior model: The moderating effect of gender. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Nambisan, P. How to profit from a better’virtual customer environment’. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 49, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantine, P.W.; Jack, R.; Parsons, A.G. Atmospheric cues and their effect on the hedonic retail experience. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Clarke-Hill, C.; Hillier, D. Retail experience stores: Experiencing the brand at first hand. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-S.; Park, J.-W. The effects of airport duty-free shop servicescape on emotional response and loyalty with an emphasis on the moderating effect of gender. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 429–448. [Google Scholar]

- Wardono, P.; Hibino, H.; Koyama, S. Effects of interior colors, lighting and decors on perceived sociability, emotion and behavior related to social dining. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, D.; Britton, T. Priceless: Turning Ordinary Products into Extraordinary Experiences; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, C.; Ivens, J. Building Great Customer Experiences; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2002; Volume 241. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, J.; Rogers, Y.; Sharp, H. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Geuens, M.; Vantomme, D.; Brengman, M. Developing a typology of airport shoppers. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, O.; Kent, A. International airport influences on impulsive shopping: Trait and normative approach. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2001, 29, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Mi Jeon, S.; Sean Hyun, S. Chain restaurant patrons’ well-being perception and dining intentions: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeskowiak, S.; Sirgy, M.J. Consumer well-being (CWB): The effects of self-image congruence, brand-community belongingness, brand loyalty, and consumption recency. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2007, 2, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hedhli, K.; Chebat, J.-C.; Sirgy, M.J. Shopping well-being at the mall: Construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H. Examining strategies for maximizing and utilizing brand prestige in the luxury cruise industry. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, K.; Hwang, J. Self-Enhancement Driven First-Class Airline Travelers’ Behavior: The Moderating Role of Third-Party Certification. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, C.; Choi, Y.G.; Hyun, S.S. Roles of Brand Value Perception in the Development of Brand Credibility and Brand Prestige; ScholarWorks: Denver, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-C.; Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Boo, H.-C.; Han, H. Understanding airline travelers’ perceptions of well-being: The role of cognition, emotion, and sensory experiences in airline lounges. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1213–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.-J.; Rahtz, D. Research on consumer well-being (CWB): Overview of the field and introduction to the special issue. J. Macromark. 2007, 27, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, N.; Singh, S.N. Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2004, 26, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J.; Rindfleisch, A.; Arsel, Z. Emotional branding and the strategic value of the doppelgänger brand image. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Parameswaran, M.; Jacob, I. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Pearson Education: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, E.R. Preface: Aesthetic decisions in computer-aided composition. Contemp. Music Rev. 2009, 28, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, D.; Wong, C.; Yip, J. How does visual merchandising affect consumer affective response? An intimate apparel experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.T.; Ng, S. Individual and situational factors influencing negative word-of-mouth behaviour. Can. J. Adm. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. De L’administration 2001, 18, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Wang, Y.-C. The influences of electronic word-of-mouth message appeal and message source credibility on brand attitude. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2011, 23, 448–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle-Thiele, S.; Maio Mackay, M. Assessing the performance of brand loyalty measures. J. Serv. Mark. 2001, 15, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Munnukka, J.; Kiuru, K. Brand love and positive word of mouth: The moderating effects of experience and price. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, E.; Akyol, A. The Mediation Role of Brand Preference on the Relationship between Consumer—Based Brand Equity and Word of Mouth Marketing. J. Bus. Res. Turk 2016, 8, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwel, S.; Lingqiang, Z.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. The Influence of Destination Image on Tourist Loyalty and Intention to Visit: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourali, M.; Laroche, M.; Pons, F. Antecedents of consumer relative preference for interpersonal information sources in pre-purchase search. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.K.; Brown, G. Understanding the relationships between perceived travel experiences, overall satisfaction, and destination loyalty. Anatolia 2012, 23, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A. The impact of tourism and travel experience on senior travelers’ psychological well-being. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, J.W.; McAlexander, J.H.; Koenig, H.F. Transcendent customer experience and brand community. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 35, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Balaji, M.; Sadeque, S.; Nguyen, B.; Melewar, T. Constituents and consequences of smart customer experience in retailing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 124, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, L.; Rossiter, J.R. A model of brand awareness and brand attitude advertising strategies. Psychol. Mark. 1992, 9, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.-H.; Chiu, C.P. The Relationships Between Brand Attitude, Customers’ Satisfaction and Revisiting Intentions of the University Students–A Case Study of Coffee Chain Stores in Taiwan. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2008, 11, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.C.; Youjae, Y. When brand attitudes affect the customer satisfaction-loyalty relation: The moderating role of product involvement. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedrich, R.W.; Swain, S.D. The influence of pioneer status and experience order on consumer brand preference: A mediated-effects model. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Liu, Y.M. The impact of brand equity on brand preference and purchase intentions in the service industries. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1687–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Luk, S.T.-K.; Cardinali, S. The role of pre-consumption experience in perceived value of retailer brands: Consumers’ experience from emerging markets. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Brand Preference and Its Impacts on Customer Share of Visits and Word-Of-Mouth Intention: An Empirical Study in the Full-Service Restaurant Segment. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Pool, J.K.; Nasrolahi Vosta, S.; Kazemi, R.V. Antecedents and consequence of consumers’ attitude towards brand preference: Evidence from the restaurant industry. Anatolia 2016, 27, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N. Linking Transformational Leadership with Nurse-Assessed Adverse Patient Outcomes and the Quality of Care: Assessing the Role of Job Satisfaction and Structural Empowerment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Relationships among green image, consumer attitudes, desire, and customer citizenship behavior in the airline industry. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator of advertising effects on brand attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ok, C.; Canter, D.D. Moderating role of a priori customer–firm relationship in service recovery situations. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, J.K. An investigation of passengers’ psychological benefits from green brands in an environmentally friendly airline context: The moderating role of gender. Sustainability 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N.; Bukhari, M.H. Assessing the Moderating Effect of Corruption on the E-Government and Trust Relationship: An Evidence of an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Sahito, N.; Hwang, J.; Hussain, A.; Manzoor, F. Can Leadership Enhance Patient Satisfaction? Assessing the Role of Administrative and Medical Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hwang, J. Measuring OPD Patient Satisfaction with Different Service Delivery Aspects at Public Hospitals in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jameel, A.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A. Good Governance and Public Trust: Assessing the Mediating Effect of E-Government in Pakistan. Lex Localis J. Local Self-Gov. 2019, 17, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Qing, M.; Hwang, J.; Shi, H. Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, Work Engagement, and Creativity: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N.; Kanwel, S. Promoting OPD Patient Satisfaction through Different Healthcare Determinants: A Study of Public Sector Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Bukhari, M.H.; Mubeen, S.; Kim, I. Improving Patient behavioral Consent through Different Service Quality Dimensions: Assessing the Mediating Role of Patient Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Rehman, H.U. The Contribution of Sustainable Tourism to Economic Growth and Employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Sirakaya, E. An examination of the antecedents and consequences of customer satisfaction. Consum. Psychol. Tour. Hosp. Leis. 2004, 3, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Hyun, S.S. Effective communication styles for the customer-oriented service employee: Inducing dedicational behaviors in luxury restaurant patrons. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokoe, E. The Conversation Analytic Role-play Method (CARM): A method for training communication skills as an alternative to simulated role-play. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2014, 47, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M. Shopping orientation and online travel shopping: The role of travel experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoteleb, S.; Aly, A.; Kamarudin, S.; Nohuddin, E.; Puteri, N. Data driven customer experience and the roadmap to deliver happiness. Mark. Branding Res. 2017, 4, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 330 | 44.5 |

| Female | 412 | 55.5 |

| Education Level | ||

| High school diploma | 170 | 22.9 |

| Associate’s degree | 35 | 4.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 464 | 62.6 |

| Graduate degree | 73 | 9.8 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 121 | 16.3 |

| Married (including divorced and widow/widower) | 621 | 83.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Company employee | 474 | 63.9 |

| Self-employed | 53 | 7.1 |

| Sales/service | 15 | 2.1 |

| Student | 13 | 1.8 |

| Civil servant | 57 | 7.7 |

| Professional | 122 | 16.4 |

| Other | 8 | 1.0 |

| Yearly income | ||

| Less than US$16,600 | 144 | 19.4 |

| US$ 16,601–US$21,600 | 139 | 18.7 |

| US$ 21,601–US$27,770 | 157 | 21.2 |

| US$ 27,771–US$37,000 | 179 | 24.1 |

| More than US$37,001 | 123 | 16.6 |

| Mean Age = 32.76 years |

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| How many times have you visited Korea, including this tour? | ||

| One time | 165 | 22.2 |

| Two times | 283 | 38.1 |

| Three times | 174 | 23.5 |

| Over four times | 120 | 16.2 |

| What is your main purpose of this tour? | ||

| Leisure | 666 | 89.8 |

| Business | 26 | 3.5 |

| To meet friends or relatives | 7 | 0.9 |

| Shopping | 43 | 5.8 |

| How long did you stay in Korea? | ||

| One night | 7 | 0.9 |

| Two nights | 73 | 9.8 |

| Three nights | 248 | 33.4 |

| Four nights | 223 | 30.1 |

| Over five nights | 191 | 25.7 |

| With whom did you travel? | ||

| Alone | 42 | 5.7 |

| Friend | 264 | 35.6 |

| Association or Company | 39 | 5.3 |

| Family or Relatives | 397 | 53.5 |

| How much did you spend for shopping? | Average | US$2560 |

| Construct | No. of Items | Mean (SD) | AVE | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Pragmatic experience | 4 | 4.23 (0.89) | 0.674 | 0.821 a | 0.768 b | 0.773 | 0.717 | 0.781 | 0.742 | 0.672 | 0.712 |

| (2) Hedonic experience | 4 | 4.10 (0.90) | 0.672 | 0.590 c | 0.820 | 0.720 | 0.739 | 0.771 | 0.667 | 0.635 | 0.658 |

| (3) Sociability experience | 4 | 3.73 (0.97) | 0.649 | 0.598 | 0.518 | 0.806 | 0.772 | 0.819 | 0.671 | 0.634 | 0.668 |

| (4) Usability experience | 4 | 4.05 (0.86) | 0.655 | 0.514 | 0.546 | 0.596 | 0.809 | 0.778 | 0.679 | 0.652 | 0.683 |

| (5) Well-being perceptions | 3 | 4.24 (0.92) | 0.701 | 0.610 | 0.594 | 0.671 | 0.605 | 0.837 | 0.690 | 0.655 | 0.718 |

| (6) Brand attitude | 6 | 4.26 (0.93) | 0.698 | 0.551 | 0.445 | 0.450 | 0.461 | 0.476 | 0.835 | 0.753 | 0.776 |

| (7) Brand preference | 3 | 4.08 (0.89) | 0.733 | 0.452 | 0.403 | 0.402 | 0.425 | 0.429 | 0.567 | 0.856 | 0.753 |

| (8) Word-of-mouth | 3 | 4.21 (0.88) | 0.718 | 0.507 | 0.433 | 0.446 | 0.466 | 0.516 | 0.602 | 0.567 | 0.847 |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 717.922, df = 0.382; χ2/df = 1.879, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.956, IFI = 0.979, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.034 | |||||||||||

| Construct and Scale Items | Cronbach Alpha | Composite Reliability (CR) | Standardized Loadings a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pragmatic Experience | 0.849 | 0.892 | |

| Worthwhile | 0.854 | ||

| Useful | 0.784 | ||

| Valuable | 0.843 | ||

| Relevant | 0.802 | ||

| Hedonic experience | 0.843 | 0.891 | |

| Pleasing | 0.793 | ||

| Exciting | 0.772 | ||

| Deeply engrossing | 0.864 | ||

| Enjoyable | 0.847 | ||

| Sociability experience | 0.840 | 0.881 | |

| Friendly | 0.733 | ||

| Personal | 0.779 | ||

| Polite | 0.781 | ||

| Inviting | 0.827 | ||

| Usability experience | 0.869 | 0.883 | |

| Not tiring | 0.805 | ||

| Not stressful | 0.820 | ||

| Not confusing | 0.811 | ||

| Consistent | 0.801 | ||

| Well-being perceptions | 0.866 | 0.876 | |

| This duty free shop played an important role in my well-being. | 0.842 | ||

| This duty free shop met my overall well-being needs. | 0.814 | ||

| This duty free shop played an important role in enhancing my quality of life. | 0.856 | ||

| Brand attitude | 0.895 | 0.899 | |

| How would you characterize your attitude toward the duty free shop? | |||

| I think my attitude toward the duty free shop is | |||

| Unfavorable—Favorable | 0.823 | ||

| Dislike—Like | 0.741 | ||

| Bad—Good | 0.790 | ||

| Unpleasant—Pleasant | 0.756 | ||

| Poor quality—High quality | 0.744 | ||

| Unsatisfactory—Satisfactory | 0.783 | ||

| Brand preference | 0.841 | 0.892 | |

| When I want to shop, I consider this duty free shop a viable choice very often. | 0.885 | ||

| This duty free shop meets my shopping needs better than other comparable duty free shops. | 0.871 | ||

| I am interested in this duty free shop more than in other comparable duty free shops. | 0.811 | ||

| Word-of-mouth | 0.886 | 0.884 | |

| I said positive things about this duty free shop to others. | 0.831 | ||

| I recommended this duty free shop to others. | 0.865 | ||

| I encouraged others to visit this duty free shop. | 0.845 |

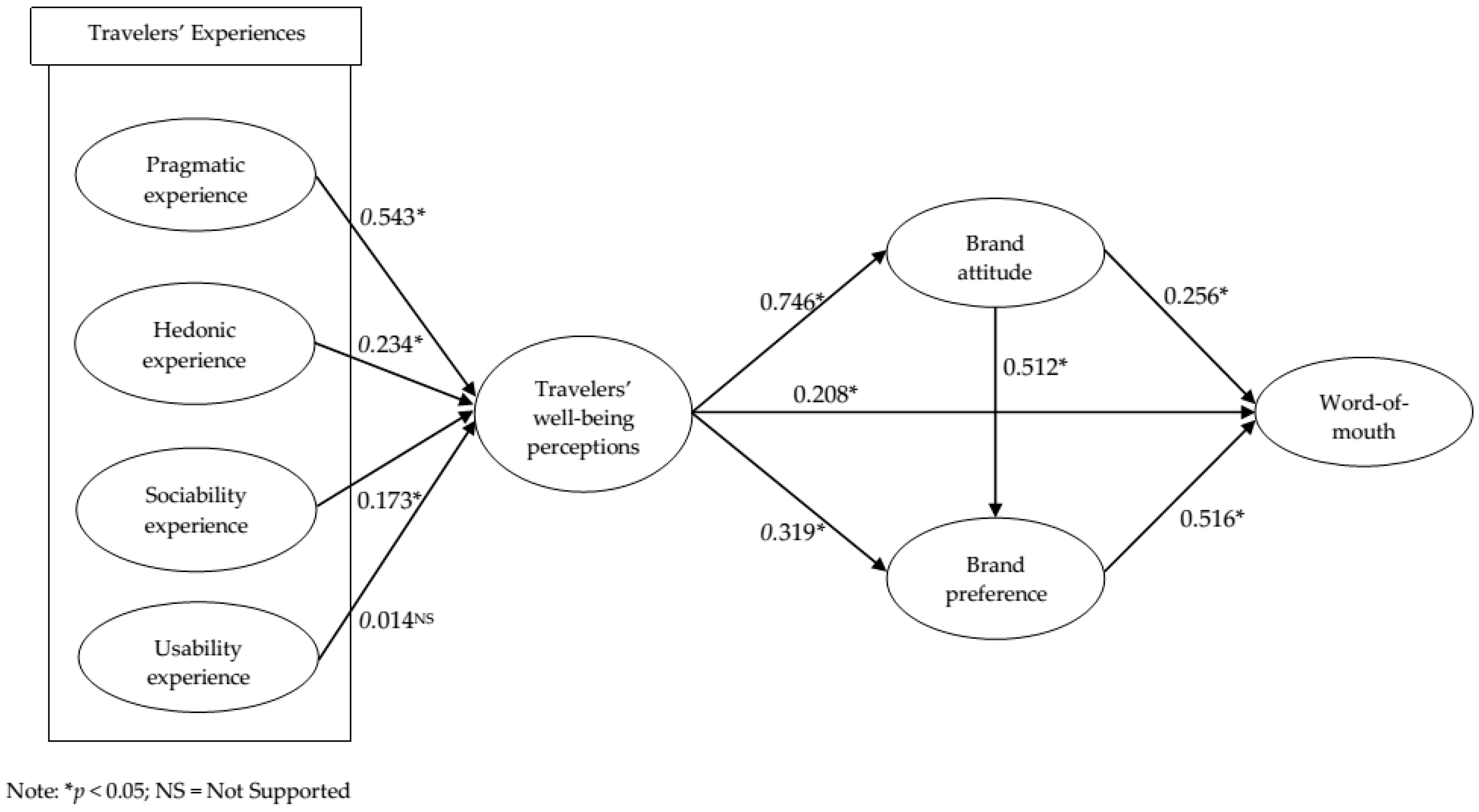

| Paths | Standardized Estimate | t-Value | Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Pragmatic experience | → | Well-being perceptions | 0.543 | 4.498 | Supported |

| H2: Hedonic experience | → | Well-being perceptions | 0.234 | 2.589 | Supported |

| H3: Sociability experience | → | Well-being perceptions | 0.173 | 1.990 | Supported |

| H4: Usability experience | → | Well-being perceptions | 0.014 | 0.805 | Not supported |

| H5: Well-being perceptions | → | Brand attitude | 0.746 | 17.208 | Supported |

| H6: Well-being perceptions | → | Brand preference | 0.319 | 6.744 | Supported |

| H7: Well-being perceptions | → | Word-of-mouth | 0.208 | 5.032 | Supported |

| H8: Brand attitude | → | Brand preference | 0.512 | 9.917 | Supported |

| H9: Brand attitude | → | Word-of-mouth | 0.256 | 5.366 | Supported |

| H10: Brand preference | → | Word-of-mouth | 0.516 | 10.080 | Supported |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 783.088, df = 398, χ2/df = 1.968, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.953, IFI = 0.976, CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.036 | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Kim, J.J.; Asif, M. The Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions: Focusing on Chinese Tourist Shopping at a Duty Free. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245081

Kim H, Kim JJ, Asif M. The Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions: Focusing on Chinese Tourist Shopping at a Duty Free. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):5081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245081

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyunjoon, Jinkyung Jenny Kim, and Muhammad Asif. 2019. "The Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions: Focusing on Chinese Tourist Shopping at a Duty Free" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 5081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245081

APA StyleKim, H., Kim, J. J., & Asif, M. (2019). The Antecedents and Consequences of Travelers’ Well-Being Perceptions: Focusing on Chinese Tourist Shopping at a Duty Free. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245081