Carrying out Physical Activity as Part of the Active Forests Programme in England: What Encourages, Supports and Sustains Activity?—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Active Forests Programme

- What are the motivations and benefits or disbenefits of undertaking physical activities in forest environments through the Active Forests programme?

- Is there evidence of sustained or changed physical activity behaviours being realised from participating in the Active Forests programme and what supports this?

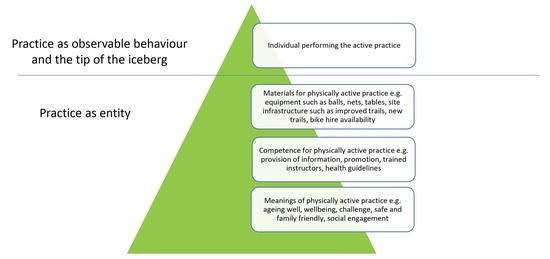

1.2. Theoretical Perspective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Analysis

2.2. Limitations of the Research

3. Results

3.1. Motivations to Be Physically Active in Forests

I have done a few runs and duathlons and stuff and this is my way of getting back into it, because I am in the middle of chemo for bowel cancer at the moment. So this is a good way of getting out into the fresh air. If I can do it anyone can.(Male, Go Tri, Dalby Forest)

Interviewer: you said it was your first time here, what encouraged you to come out and do Buggy Fit.

Participant: To get my body back and to meet new people.(Female, Buggy Fit, Whinlatter Forest)

So, when my children grew up my youngest one at that point was eighteen, so I decided to do stuff for myself. I have always taken then to rugby, ballet dancing, fitness but never thought about myself.(Female, Go Tri, Dalby Forest)

I think the mental health side is huge, but also I am really conscious as a woman of a certain age we aregetting to a point where strength work is really important.(Female, Bootcamp, Alice Holt Forest)

Female 1: Men are too competitive and change the dynamic and the conversation.

Female 2: And they bump you off the trails, they are behind you with their breaks on.(Females, Real spin, Bedgebury Forest)

‘Running you can just do from your front door, but I’d never do this sort of exercise [e.g., star jumps, press ups etc.], so you need a bit of a class’.(Female, Bootcamp, Alice Holt Forest)

Female 1: It’s taken me two years to persuade her actually

Interviewer—what finally tipped you into coming

Female 2: I couldn’t put her off any longer, but now I wonder why I didn’t do this sooner. So I’ve enjoyed it a lot more than I anticipated.(Females, Nordic fitness walking, Haldon Forest)

Female 1: My son started mountain biking at school ‘cause he wanted to follow what I was doing

Female 2: It’s good for your children to see you going out and doing things, you get out of your comfort zone.(Females, Real Spin, Bedgebury Forest)

I’m trying to get back into being active after a gap, to encourage the children to have active lifestyles.(Male, Parkrun, Sherwood Pines Forest)

3.2. Enablers to Being Physically Active in Forests

Cause J is trained in post-natal fitness it is much easier going to her—someone who understands a lot of the problems you get during and after pregnancy. It makes it a lot easier than just going to an exercise class and they don’t know what to do or exacerbate the problem.(Female, Buggy Fit, Whinlatter Forest)

You never find yourself looking at your watch and thinking when’s it end. I love it because it’s different all the time.(Female, Pilates, Delamere Forest)

Oh yes you have to keep it up, we go twice a week.(Female, Pilates, Delamere Forest)

This is the great thing about this place you can spend the whole day and if they [the children] get bored you can move on to the next thing.(Male, Table tennis, Thetford Forest)

I also love the fact that you can just come, you don’t have to worry about bringing your bike. That is a huge advantage because I used to bring my own bike but there is lifting it in and lifting it out of the car.(Female, Real Spin, Bedgebury Forest)

I think the reason so many women like running in the forest is there are no vans, no cars, no one can see you, no blokes, there is no car going beep beep.(Female, Bootcamp, Alice Holt Forest)

3.3. Benefits of Being Physically Active in Forests

Female 1: I think that is the nub, mental health even more than physical activity

Female 2: I run out my crazy—that is what I tell people.(Females, Bootcamp, Alice Holt Forest)

‘I’ve never really had a problem with motivation it’s just I’ve had a really bad history of depression when I was younger which still comes back from time to time and the only sure fire success for me is running, it always lifts my mood’.(Female, Parkrun, Sherwood Pines Forest)

If I get out there is an immediate impact so it can help with day to day living and mental health.(Female, Real Spin, Bedgebury Forest)

I find running relaxing if I’ve had a hard day at work, I have a hard run which is relaxing.(Male, Orienteering, Cannock Chase Forest)

That’s why I started coming cause I came on my own and then I fell off and it’s a bit miserable falling off on your own and that is why I joined the group.(Female, Real Spin, Bedgebury Forest)

D and I are retired so it’s nice to come out and meet other people even for just an hour or so. Even in the winter when you wouldn’t really go out, it gets you out of the house.(Male, Pilates, Delamere, Forest)

I was recommended to do this by a physio as I have a really bad right knee and I was running but she said try cycling as its low impact. I didn’t imagine it was but it’s been great. Yes my knees are so much better definitely.(Female, Real Spin, Bedgebury Forest)

Its particularly about strength, core strength and flexibility particularly for people with back problems.(Male, Pilates, Delamere Forest)

I’m a lorry driver by trade, so all week I’m sat on my backside running up the country, so I’m trying to cram everything in to 2 days on a weekend. I’ve just completed it in just over an hour—so that will do.(Male, Go Tri, Dalby Forest)

It teaches self-reliance, you might be on your own in the woods with a map but kids have to sort it out and these are life skills. The skills translate to other things.(Male, Orienteering, Cannock Chase Forest)

The forest is very varied, so you always have an interesting view and on a hot day you have the dappled shade as well which is lovely.(Female, Nordic fitness walking, Haldon Forest)

It’s on my doorstep, I’ve been coming up here all my life. There’s been a huge change [in the forest] but for the good. I think it brings people in, the facilities up here now are brilliant and it’s great, it gets people outside and that is not a bad thing.(Male, Go Tri, Dalby Forest)

I thought I knew the forest but. there are so many paths we go on, it’s absolutely wonderful.(Female, Nordic walking, Delamere Forest)

Here it’s a nice atmosphere and the scenery is really great. It takes us 25 min to get here but it’s a nice place to come.(Male, Parkrun, Sherwood Pines Forest)

There are changes in the seasons, you are more observant of what is around you. You look and listen for things.(Female, Nordic walking, Delamere Forest)

3.4. Disbenefits

‘Fear of people, there are some very strange people in the forest sometimes’.(Female, Nordic walking, Delamere Forest)

3.5. Sustaining or Changing Physical Activity Practices

My first run was 12 weeks ago. It’s made a massive, massive difference. I’ve lost one stone and nine pounds and I’ve come off anti-depressents. It just keeps me going. I come [to Parkrun at Sherwood Pines] with my niece, I never thought my niece would want to come with me. So now we come every week and have aunty and niece time together’.(Female, Parkrun, Sherwood Pines Forest)

Interviewer: What motivated you to join Buggy Fit?

Female 1: I can’t spend all day in the house with her [the baby] it would drive me mad

Female 2: I was really depressed when I first had the baby as I thought I was never going to walk up hill again.(Buggy Fit, Whinlatter Forest)

I didn’t start doing any fitness until I was thirty. I was three stone heavier than I am now, drank a lot, eat a lot. Since then I have been in and out of running’.(Male, Parkrun, Sherwood Pines Forest)

I’ve got more into fitness in recent years, as you get older it’s about looking after yourself.(Male, Go Tri, Dalby Forest)

‘Yes without a doubt the Real Spin has inspired me’.(Female, Real Spin, Bedgebury Forest)

4. Discussion

4.1. Social Practices and the Active Forests Programme

4.2. Moving beyond a Focus on Individual Behaviours

4.3. Forests as Spaces for Women to Be Comfortable in Being Physically Active

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Site Name | Bedgebury Forest | Thetford Forest | Sherwood Pines Forest | Delamere Forest | Dalby Forest |

| Active Forests coordinator % of time spent on AFP1 | 80% | 80% | 80% | 80% | 80% |

| Forest size in hectares approximately2 | 890 | 22,500 | 1500 | 1000 | 3575 |

| Forest type3 | Includes the national pinetum and wider mixed species forest | Largest lowland pine forest in Britain including heaths and broadleaves | Pine forest | Mixed conifer and deciduous | Mixed conifer and deciduous |

| Location | Kent | On the Norfolk/Suffolk border | Nottinghamshire | Cheshire | North Yorkshire |

| Some of the new organised events/activities developed | Parkrun Archery, Table tennis Orienteering | Family fitness Gruffalo orienteering Cycling Table tennis Parkrun | Parkrun Gruffalo orienteering Football Volleyball Pilates Running | Bootcamp Running Family fitness Table tennis Orienteering Cycling | Netball, Nordic walking, Family fitness, Table tennis, Gruffalo orienteering |

| Site Name | Birches Valley Cannock Chase | Forest of Dean | Salcey Forest | Alice Holt Forest | Haldon Forest Park |

| Active Forests coordinator | 80% | 80% | 80% | 80% | 80% |

| Forest size in hectares approximately | 1200 | 7500 | 500 | 848 | 1725 |

| Forest type | Mixed woodland | Mixed woodland Includes several different woods | Mixed woodland including ancient oaks | Mixed woodland | Mixed woodland. Includes several different woods |

| Location | Staffordshire | Gloucestershire | Northamptonshire | Surrey | Devon |

| Some of the new organised events/activities developed | Yoga, Archery, Volleyball, Table tennis, Mountain biking, Junior Parkrun | Nordic walking, Mountain biking, Football, Orienteering, Cycle events | Walking groups, Buggy Fit, Archery, Running events | Walking group Running group, Canicross, Buggy Fit, Bootcamp Orienteering | Yoga, Table tennis, Parkrun, Running events, Orienteering, Mountain biking, Fitness, Bootcamp |

| Site Name | Wendover Forest | Whinlatter Forest | Thames Chase | Chopwell Wood | Jeskyns Community Woodland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Forests coordinator | 80% | 80% | 80% | ||

| Forest size in hectares approximately | 321 | 1200 | 41 | 375 | 150 |

| Forest type | Mixed woodland | Mixed woodland | Community Woodland on former farm | Mixed woodland | New planted woodland on former farm. |

| Location | Buckinghamshire | Cumbria | London outskirts (urban) | Gateshead (urban) | Kent (urban) |

| Some of the new organised events/activities developed | Walking groups, Volleyball, Table tennis, Running events, Pilates, Buggy Fit, Parkrun | Walking group, Running events, Pilates, Orienteering, Climbing | Type II diabetes sessions and walking, Running events | Holiday hunger activities, | Running events, Children’s glow trail |

| Site Name | Hamsterley | Wyre Forest | Westonbirt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Forests coordinator | 80% | 80% | 80% |

| Forest size in hectares approximately | 2200 | 1915 | 242 |

| Forest type | Mixed woodland | Mixed woodland | The National Arboretum. Picturesque parkland landscape |

| Location | County Durham (peri-urban) | Worcestershire | Gloucestershire |

| Some of the new organised events/activities developed | Running events, Children’s glow trail | Walking group, Volleyball, Table tennis, Running group, Nordic Walking, Buggy Fit, Canicross | Yoga, Tai Chi, Table tennis, Nordic Walking, Duathlon |

Appendix B. Active Forests Topic Guide for Focus Groups/Interviews

- -

- When did you first got involved in sport and physical activity [prompt: what age. What activities]

- -

- What motivated you to get involved in sport and physical activity [prompt: fitness, health, enjoyment,]

- -

- How you got it involved [on your own, at school, joining an organised activity, going to an event, joining a club]

- -

- How regularly do you undertake physical activity [everyday, every week, month]

- -

- Do you consider yourself to be a sport and exercise type of person [prompt: do you view [insert name of sport] as a sport?

- -

- Do you think you are meeting the recommendation of 150 min of a mix of moderate and vigorous activity per week? [could include active travel, gardening as well as leisure activity]

- -

- When did you first get involved in physical activity in a woodland environment (Prompt: what type of activities do you do in woodlands)

- -

- Has anyone not done this [name activity] type of activity before?

- -

- What motivated you to do this?

- -

- How regularly do you do this activity in a forest environment?

- -

- Do you do this and/or other physical activity in other outdoor places (non-woodland i.e., parks, country parks, countryside, etc.)?

- -

- What is the balance between activity you do in the forest/outdoors and in other places?

- -

- What do you base your decisions on concerning whether you do your exercise in the forest or elsewhere?

- -

- What is your experience of undertaking physical activity in a woodland?

- -

- What are the benefits—are they different from doing sport in other locations—sports centres/gyms/sports fields? [prompt: fresh air, sensory stimulation, views, challenges—see next question]

- -

- What are the challenges [prompt: weather, facilities, getting to woodland, uneven terrain, getting to location, cost of parking and events]

- -

- Is there anything that would make it easier for you to do physical activity in a woodland [prompt: facilities, organised activities, infrastructure improvement i.e., better trails]

- -

- Has participating in this physical activity in this woodland led to any changes in your behaviour? [prompt: doing a new activity, sustaining behaviour in long term, changing behavior—doing more or different types of activity, doing more exercise overall, other such as encouraging a friend to join you].

- -

- Has getting involved in this physical activity in this forest led you to visit it more often [prompt: how often—once a week more, once a month more etc.]

- -

- How important is it for you to join an organised exercise activity in woodland that is led by someone [prompt: if it is important why is that the case, would you still do it if you were on your own]

- -

- How important to you is undertaking physical activity in woodlands with others whether family, friends etc.

- -

- Have you met new people through this activity, does this play any part in motivating you to attend or do you do activity with friends/family?

- -

- What is your experience of the social side of this activity, would you do the activity alone?

- -

- What is the importance or not of different aspects of woodlands—visual (what you see), sound (what you hear), smell (what you smell), texture (textures you see or feel by hand or underfoot) to your experience and any impact on your health and wellbeing.

- -

- Is there anything specifically enables you to use this wood and others—[prompt: it’s nearby, organised activities, having dog to walk, going with someone else/company, familiarity with site, meeting new people, personal motivation]

References

- British Heart Foundation. Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior—Report 2017; British Heart Foundation: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017 (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Public Health England. Physical Activity: Applying All Our Health; Public Health England: London, UK, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health. (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Heath, G.W.; Parra, D.C.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Andersen, L.B.; Owen, N.; Goenka, S.; Montes, F.; Brownson, R.C. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: Lessons from around the world. Lancet 2012, 380, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Physical Activity: Walking and Cycling—Public Health Guideline PH41; NICE: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/PH41/chapter/1-Recommendations#policy-and-planning (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Gerber, M.; Puehse, U. Review article: Do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scand. J. Public Health 2009, 37, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mello, M.T.; Vde Lemos, A.; Antunes, H.K.; Bittencourt, L.; Santos-Silva, R.; Tufik, S. Relationship between physical activity and depression and anxiety symptoms: A population study. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegberg, N.J.; Tone, E.B. Physical activity and stress resilience: Considering those at-risk for developing mental health problems. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2015, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molanorouzi, K.; Khoo, S.; Morris, T. Motives for adult participation in physical activity: Type of activity, age and gender. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egli, T.; Bland, H.W.; Melton, B.F.; Czech, D.R. Influence of Age, Sex, and race on college Students’ exercise motivation of physical activity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, E.; Stavreski, B.; Jennings, G.L.; Bronwyn, A.; Kingwell, A. Exploring motivation and barriers to physical activity among active and inactive Australian adults. Sports 2017, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport England. Go Where Women Are: Insight in Engaging Women and Girls in Sport and Exercise; Sport England: London, UK, Undated; Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/media/3285/gowherewomenare_final_01062015final.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Gavin, J.; Keough, M.; Abravenel, M.; Moudrakovskil, T.; McBrearty, M. Motivations for participation in physical activity across the lifespan. Int. J. Wellbeing 2014, 4, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caperchione, C.; Vandelanotte, C.; Kolt, G. What a man wants: Understanding the challenges and motivations to physical activity participation and health eating in middle-aged Australian men. Am. J. Men’s Health 2012, 6, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO European Regional Office. Infographic: Make Physical Activity a Part of Daily Life during All Stages of Life. 2015. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/physical-activity/data-and-statistics/infographic-make-physical-activity-a-part-of-daily-life-during-all-stages-of-life (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Thompson Coon, J.; Boddy, K.; Skein, K.; Whear, R.; Barton, J.; Depledge, M. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Everybody Active, Everyday: An. Evidence Based Approach to Physical Activity; Public Health England: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hunter, R.; Christian, H.; Veitch, J.; Astell-Burt, T.; Schipperijn, J. The impact of interventions to promote physical activity in urban green space. A systematic review and recommendations for future research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 124, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jansen, F.M.; Ettema, D.F.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Pierik, F.H.; Dijst, M.J. How do type and size of natural environments relate to physical activity behavior? Health Place 2017, 46, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, M.C.; Jacoby, S.F.; South, E.C. Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments. Health Place 2018, 51, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 91, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperjin, J.; Bentsen, P.; Troelsen, J.; Toftager, M.; Stigsdotter, U. Associations between physical activity and characteristic of urban green space. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.; Morris, J. Well-being for all? The social distribution of benefits gained from woodlands and forests in Britain. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 356–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport England. Getting Active Outdoors: A Study of Demography, Motivation, Participation and Provision in Outdoor Sport and Recreation in England; Sport England: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, L.; Forster, J. Fun and Fitness in the Forest: Monitoring and Evaluation of the Three Year Active Forests Pilot Programme; Forest Research: Farnham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spurling, N.; McMeekin, A.; Shove, E.; Southerton, D.; Welch, D. Interventions in Practice: Re-Framing Policy Approaches to Consumer Behaviour; Sustainable Practices Research Group: 2013. Available online: http://www.sprg.ac.uk/uploads/sprg-report-sept-2013.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2010, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, L.; Morris, J.; Stewart, A. Engaging with peri-urban woodlands in England: The contribution to people’s health and well-being and implications for future management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6171–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, J.; O’Brien, L. Encouraging healthy activity amongst under-represented groups: An evaluation of the Active England woodland projects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; van Dillen, S.; Verheij, R.; Groenewegen, P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, L.; Forster, J. Sustaining and changing physical activity behaviours in the forest: An evaluated pilot intervention on five public forest sites in England. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, D.; Douglas, F.; Hoddinott, P.; Van Teijlingen, E.; Stewart, F.; Robertson, C.; Boyers, D.; Avenell, A. A qualitative evidence synthesis on the management of male obesity. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lewis, K.; Fraser, C.; Manby, M. ‘Is it worth it?’ A qualitative study of the beliefs of overweight and obese physically active children. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Social and Economic Research Group. SERG Research Ethics; Forest Research: Farnham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, C. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coleman, L.; Cox, L.; Roker, D. Girls and young women’s participation in physical activity: Psychological and social influences. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 23, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcu, A.; Uzzell, D.; Barnett, J. Making sense of unfamiliar risks in the countryside: The case of Lyme disease. Health Place 2011, 17, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.; Marcu, A.; Marzano, M.; Barnett, J.; Quine, C.P.; Uzzell, D. Situating risk in the context of a woodland visit: A Case Study on Lyme Borreliosis. Scott. For. 2012, 66, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bosteder, S.M.; Appleby, K.M. Naturally fit: An investigation of experiences in a women only outdoor recreation program. Women Sport Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behaviour; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, W.; Johnston, M.; Johnston, D.W.; Bonetti, D.; Wareham, N.J.; Kinmonth, A.L. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour in Behaviour Change Interventions: A systematic review. Psychol Health 2002, 17, 123–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Hallsworth, M.; Halpern, D.; King, D.; Metcalfe, R.; Vlaev, I. MINDSPACE: Influencing Behaviour through Public Policy; Cabinet Office and The Institute for Government: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal, B.; Yan, Z.; Cardinal, M. Negative experiences in physical education and sport: How much do they affect physical activity participation later in life? J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2013, 84, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Elements of the AFP and Types of Physical Activities Offered | Examples |

|---|---|

| Changes and improvements to the existing forest site infrastructure | New or improved running, orienteering, cycling trails |

| Provision of equipment for activity | Table tennis tables and bats, goals and footballs, volleyball nets and balls, rounders bats and balls provided at some sites. This can also include the use of phone apps, e.g., a Gruffalo spotter app was developed so the users could follow clues such as a Gruffalo footprint, and when they find it a short animation of the character is triggered which blends in with the natural surroundings. |

| Organised and led regular weekly activities these: Are led by trained instructors or volunteers Take place on a regular basis, e.g., weekly—although they may stop during school holidays | Nordic walking, park run 1, Pilates, fitness, tai chi, archery, buggy fit, Bootcamp. There can be overlap between activities, e.g., running can be self-led or part of an event or part of a class led by an instructor. |

| Organised events (one off, sporadic or yearly events) | 10 Km runs, duathlons, fun runs, cycle events, canicross 2, orienteering |

| Self-led activities | Table tennis, Gruffalo 3 orienteering, running, cycling, mountain biking, volleyball, rounders, badminton, cricket, football, tennis, walking |

| Communication and marketing | To publicise the programme and develop new opportunities to promote physical activity. |

| Forest Location | Activity | Area of Country | Interview/Focus Group | Age Range of Participants | Male | Female | Employment Status | Disability or Limited in Daily Activities | Month/Year of Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delamere Forest | Nordic walking | North west | Focus group | 55–74 | 1 | 10 | Working 1, Retired 10 | None | October 2015 |

| Sherwood Pines Forest | Parkrun | Midlands | Interviews and mini focus group | 25–64 | 3 | 10 | Retired 1 Employed 7 Self-employed 3 Student 1 | 1 person | February 2016 |

| Bedgebury Forest | Real Spin (mountain biking for women) | South east | Focus group | 35–54 | 0 | 9 | Retired 1 Employed 3 Self-employed 1 Looking after family 4 | None | February 2016 |

| Cannock Chase Forest | Orienteering | Midlands | Focus group | 13–75+ | 10 | 4 | Not given | None | August 2016 |

| Dalby Forest | Go Tri (duathlon) | North east | Interviews | 25–64 | 9 | 5 | No data | No data | February 2017 |

| Haldon Forest | Nordic fitness walking | South west | Focus group | 45–75+ | 1 | 10 | Retired 8 Employed 2 Looking after family 1 | 7 persons | April 2018 |

| Thetford Forest | Table Tennis | South east | Interviews | 35–74 | 5 | 9 | No data | No data | April 2018 |

| Delamere Forest | Pilates | North west | Focus group | 25–75+ | 3 | 5 | Retired 5 Employed 1 Self-employed 2 | None | April 2018 |

| Whinlatter Forest | Buggy Fit | North west | Focus group | 16–44 | 0 | 5 | Employed 2 Looking after family 1 Maternity leave 2 | None | May 2018 |

| Dalby Forest | Canicross | North east | Interviews | 16–64 | 3 | 8 | No data | No data | September 2018 |

| Alice Holt Forest | Bootcamp | South east | Focus group | 35–54 | 0 | 10 | Employed 2 Looking after family 4 Self-employed 4 | None | June 2019 |

| Total | 35 men | 85 women |

| Benefits | Responses from Participants and Observational Field Notes | Activity and Forest Site |

|---|---|---|

| Social | ‘Because there are groups like the ‘run fit mums’ and this [Bootcamp] which is all so social as well’ ‘It all adds to being more supportive and encouraging for others to come along ‘It’s very social’. ‘Yes, you can have a chat’ ‘You have like-minded people, so you talk a lot’ ‘And then they are having an enjoyable day not just with their family but with strangers as well’ ‘Yes, we always go for a drink afterwards in the café, we try and make it a social and family activity as well’ | Alice Holt Forest, Bootcamp Haldon Forest and Delamere Forest, Nordic walking Dalby Forest, Go Tri Sherwood Forest, Parkrun |

| Escape and freedom | Interviewer: what is it about being outside? ‘Freedom’ ‘We enjoy the feeling of freedom’ ‘I feel like a child again—freedom, it’s lovely’ | Whinlatter Forest, Buggy Fit Bedgebury Forest, Real Spin |

| Learning and skills | ‘It’s learning the different aspects of Nordic walking, how to use the poles, how to exercise, how to warm up and cool down and a bit of health and safety’ | Delamere Forest, Nordic walking |

| Sense of achievement | ‘It challenges you, it’s not something you do for a rest Nordic walking’ | Delamere Forest, Nordic walking |

| Mental health | ‘You can go at your own pace you’re not pressured into doing anything’ | Delamere Forest, Nordic walking |

| Fresh air | ‘The fresh air, the trees it is so good for us’ ‘But if you go for a walk you want to be breathing in fresh air, away from the traffic and diesel fumes’ | Alice Holt Forest, Bootcamp Delamere Forest, Nordic walking |

| Physical | ‘Trying to be healthier, lose weight in my case’ ‘I need to get back into it as well as I have had a health issue as well. I have just been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, so he has cancer and I have this, so we are a right pair’ | Sherwood Forest, Parkrun Dalby Forest, Go Tri |

| Forest environment | ‘You’ve got the challenge of uneven terrain and some hills and then level ground That’s when you realise how good two poles are because it makes it so much easier walking with poles’ ‘We love the forest, know it well, have used it for many years. We have seen changes that have taken place in the forest over the past years. Now it is appealing to more diverse groups of people. We think the forest is beautiful, we are always seeing different things’ | Delamere Forest, Nordic walking Dalby Forest, Go Tri |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Brien, L. Carrying out Physical Activity as Part of the Active Forests Programme in England: What Encourages, Supports and Sustains Activity?—A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245118

O’Brien L. Carrying out Physical Activity as Part of the Active Forests Programme in England: What Encourages, Supports and Sustains Activity?—A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(24):5118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245118

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Brien, Liz. 2019. "Carrying out Physical Activity as Part of the Active Forests Programme in England: What Encourages, Supports and Sustains Activity?—A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 24: 5118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245118

APA StyleO’Brien, L. (2019). Carrying out Physical Activity as Part of the Active Forests Programme in England: What Encourages, Supports and Sustains Activity?—A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245118