Household Food Insecurity Narrows the Sex Gap in Five Adverse Mental Health Outcomes among Canadian Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Household Food Insecurity in Canada and Adverse Mental Health Outcomes

1.2. Household Food Insecurity, Gender/Sex, and Mental Health

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Household Food Security Survey Module

2.3.2. Mental Health Outcome Variables

2.3.3. Demographic and Socioeconomic Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

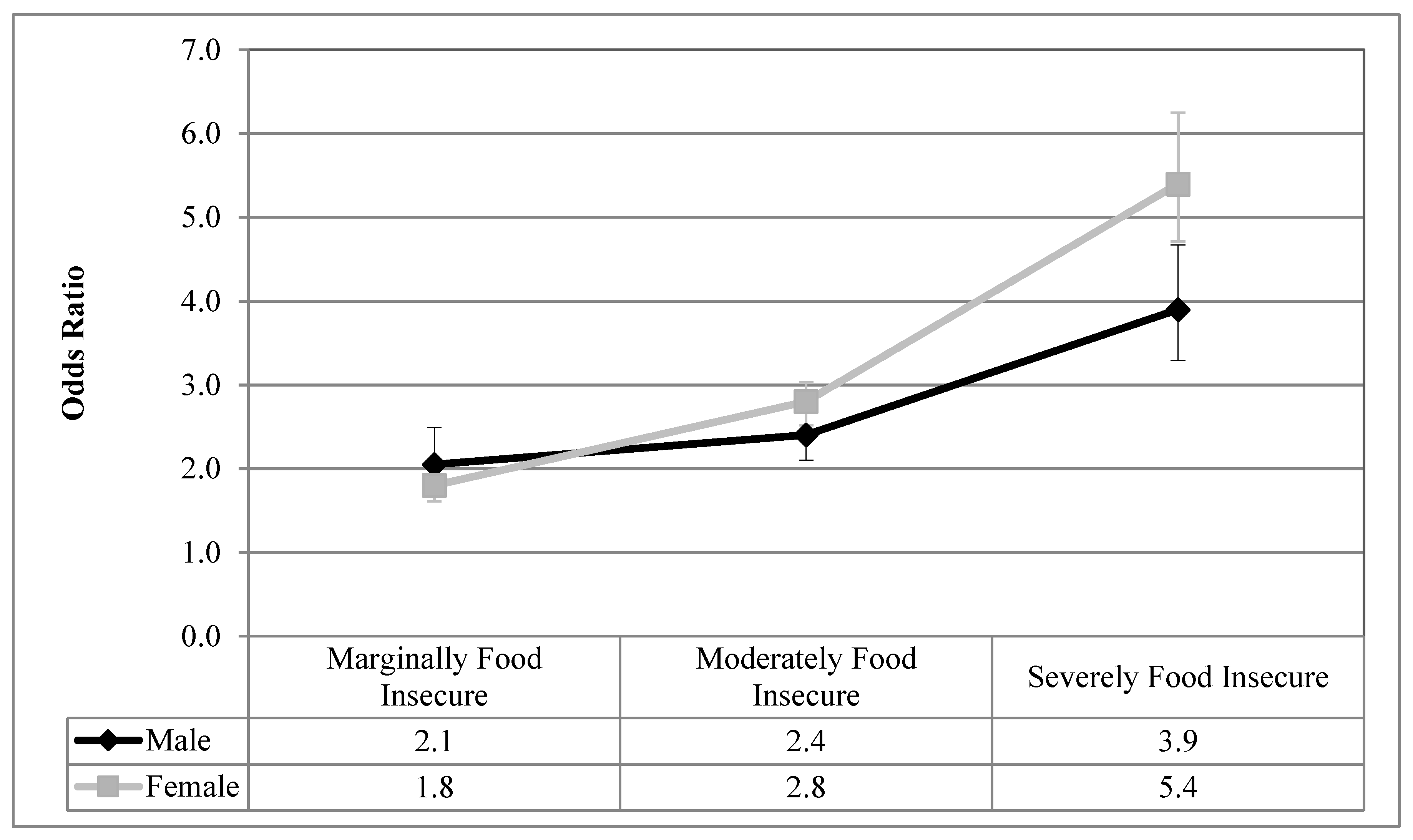

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Level of Household Food Insecurity | Description of Level | Number of Affirmative Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Food Secure | No financial constraints on the ability to fill household’s food need. | 0 to adult or child food situation questions |

| Marginally Food Insecure | Worry about running out of food due to financial constraints. | 1 food situation question |

| Moderately Food Insecure | Reductions in quality and/or quantity of food due to financial constraints. | 2–5 adult food situation questions or 2–4 child food situation questions |

| Severely Food Insecurity | Reductions in food intake, missing meals and at its most extreme going a full day without food. | 6+ adult food situation questions or 5+ child food situation questions |

Appendix B

| Name of Variable | Level of Measurement | Survey Question | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Thoughts in the Past Month | Binary (Yes, No) | “During the past month, about how often did you feel sad or depressed?” | Those who responded all of the time, most of the time, some of the time were coded into the “yes” group. All other respondents were coded into the “no” group. |

| Major Depressive Episodes in the Past Year | Binary (Yes, No) | The Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) measures Major Depressive Episodes (MDE). This subset of questions assesses the depressive symptoms of respondents who felt depressed or lost interest in things for 2 weeks or more in the last 12 months. Respondents are screened into the CIDI-SF based on affirmative responses to the following 2 screening questions, if a respondent answers affirmatively to the screening questions, their depression level is measured based on 7 additional questions. | The classification of depression is based on an affirmative response to the original screening question and 5 out of 9 of the depression questions. This corresponds to a 90% predictive probability of caseness, which closely aligns with the DSM-5 diagnostic guidelines for MDE in adults [53]. This probability expresses the chance that the respondent would have been diagnosed as having experienced a Major Depressive Episode in the past 12 months had they completed the CIDI Long-Form [30]. |

| Anxiety Disorder | Binary (Yes, No) | “Do you have an anxiety disorder such as phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder or a panic disorder?” | Respondents are reminded that the question is only referring to those conditions diagnosed by a health professional. |

| Mood Disorder | Binary (Yes, No) | “Do you have a mood disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia?” | Respondents are reminded that the question only refers to those conditions diagnosed by a health professional. |

| Suicidal Thoughts in the Past Month | Binary (Yes, No) | “Have you ever seriously considered committing suicide or taking your own life? Has this happened in the past 12 months?” | This variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable. In addition, those who answered “not applicable: were coded into the “no” group, given they answered negatively to this question in an earlier prompt. |

| Self-Reported Mental Health Status | Binary (Fair/Poor, Good/Very Good/Excellent) | “In general, would you say your mental health is: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” | This variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable. “Fair/poor” or “Good/very good/excellent”. This variable has been validated and is a reliable measure of general mental health [54]. |

References

- ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Bernert, S.; Bruffaerts, R.; Brugha, T.S.; Bryson, H.; de Girolamo, G.; de Graaf, R.; Demyttenaere, K.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 109, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazer, D.G.; Kessler, R.C.; McGonagle, K.A. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.R.; Rush, A.J.; Walters, E.E.; Wang, P.S. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder. JAMA 2003, 289, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C. Epidemiology of women and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2003, 74, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, S.B.; Williams, J.V.A.; Lavorato, D.H.; Wang, J.L.; Bulloch, A.G.M.; Sajobi, T. The association between major depression prevalence and sex becomes weaker with age. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, R.W. Revisiting the relationship among gender, marital status, and mental health. Am. J. Sociol. 2002, 107, 1065–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.L.; Lasiuk, G.; Norris, C. The relationship between sexual orientation and depression in a national population sample. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 3522–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Mitchell, A.; Dachner, N. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2012; PROOF: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; Available online: http://proof.utoronto.ca/resources/proof-annual-reports/ (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security; United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Services: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2000.

- Health Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey. Cycle 2.2, Nutrition (2004)—Income-Related Household Food Security in Canada. 2007. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/surveill/income_food_sec-sec_alim-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Gucciardi, E.; Vogt, J.A.; DeMelo, M.; Stewart, D.E. Exploration of the relationship between household food insecurity and diabetes in Canada. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 2218–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Mitchell, A.; McLaren, L.; McIntyre, L. Chronic physical and mental health conditions among adults may increase vulnerability to household food insecurity. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozoris, N.T.; Tarasuk, V.S. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galesloot, S.; McIntyre, L.; Fenton, T.; Tyminski, S. Food insecurity in Canadian adults receiving diabetes care. Can. J. Pract. Res. 2012, 73, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, K.; Kaplan, B. Food insecurity in adults with mood disorders: Prevalence estimates and associations with nutritional and psychological health. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2015, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heflin, C.M.; Siefert, K.; Williams, D.R. Food insufficiency and women’s mental health: Findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siefert, K.; Heflin, C.M.; Corcoran, M.E.; Williams, D.R. Food insufficiency and physical and mental health in a longitudinal survey of welfare recipients. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 22, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Epel, E.S.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; Laraia, B.A. Household food insecurity is positively associated with depression among low-income Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants and income-eligible nonparticipants. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker, R.C.; Phillips, S.M.; Orzol, S.M. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muldoon, K.A.; Duff, P.K.; Fielden, S.; Anema, A. Food insufficiency is associated with psychiatric morbidity in a nationally representative study of mental illness among food insecure Canadians. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessiman-Perreault, G.; McIntyre, L. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 3, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, C.; Crooks, D.L. Coping and the biosocial consequences of food insecurity in the 21st century. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 149, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnels, V.E.; Kristjansson, E.; Calhoun, M. An investigation of adults’ everyday experiences and effects of food insecurity in an urban area in Canada. Can. J. Community Ment. Health 2011, 30, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, M.; Caspi, A.; Howard, L.M.; Ambler, A.P.; Bolton, H.; Mountain, N.; Moffitt, T.E. Mental health context of food insecurity: A representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehler, C.; Weinreb, L.F.; Huntington, N.; Scott, R.; Hosmer, D.; Fletcher, K.; Goldberg, R.; Gundersen, C. Risk and protective factors for adult and child hunger among low-income housed and homeless female-headed families. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, L.; Officer, S.; Robinson, L.M. Feeling poor: The felt experience of low-income lone mothers. Affilia 2003, 18, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C. Food insecurity in women: A recipe for unhealthy trade-offs. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 20, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelin, A.-M.; Beaudry, M.; Habicht, J.-P. Characterization of household food insecurity in Quebec: Food and feelings. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M. An intersectional approach to men’s health. J. Mens Health 2012, 9, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. User Guide, Public-Use 2007–2008: Microdata File, Canadian Community Health Survey; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fram, M.S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Jones, S.J.; Williams, R.C.; Burke, M.P.; DeLoach, K.P.; Blake, C.E. Children are aware of food insecurity and take responsibility for managing food resources. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, J.C.H.; Fleisch, V.C.; McIntyre, L. Legislated changes to federal pension income in Canada will adversely affect low income seniors’ health. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.; Burchett, B.; Service, C.; George, L.K. The association of age and depression among the elderly: An epidemiologic exploration. J. Gerontol. 1991, 46, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inuit Circumpolar Council. Food Security Across the Arctic. 2012. Available online: http://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/uploads/3/0/5/4/30542564/icc_food_security_across_the_arctic_may_2012.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Statistics Canada. User Guide, Public-Use 2005: Microdata File, Canadian Community Health Survey; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. User Guide, Public-Use 2009–2010: Microdata File, Canadian Community Health Survey; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.T.; Frank, D.A.; Berkowitz, C.; Black, M.M.; Casey, P.H.; Cutts, D.B.; Meyers, A.F.; Zaldivar, N.; Skalicky, A.; Levenson, S.; et al. Community and international nutrition food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K.M.; Marshall-Fabien, G.L.; Tecson, A. Association of moderate and severe food insecurity with suicidal ideation in adults: National survey data from three Canadian provinces. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, L.; Wu, X.; Fleisch, V.C.; Emery, H.J.C. Homeowner versus non-homeowner differences in household food insecurity in Canada. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2015, 14, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. The Consumer Price Index; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Trends in Income-Related Health Inequalities in Canada: Methodology Notes; Canadian Institute for Health Information: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peel Public Health. Health in Peel: Determinants and Disparities; Peel Public Health: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mens-Verhulst, J.; Radtke, L. Intersectionality and Mental Health: A Case Study. 2008. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56fd7e0bf699bb7d0d3ff82d/t/593ab6522e69cf01a44b14d4/1497019986918/INTERSECTIONALITY+AND+MENTAL+HEALTH2.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Galdas, P.M.; Cheater, F.; Marshall, P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 49, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kartalova-O’Doherty, Y.; Doherty, T.D. Recovering from recurrent mental health problems: Giving up and fighting to get better. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 19, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, K.N.; Kruse, K.; Blakely, T.; Collings, S. The association of food security with psychological distress in New Zealand and any gender differences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loopstra, R.; Tarasuk, V. Food bank usage is a poor indicator of food insecurity: Insights from Canada. Soc. Policy Soc. 2015, 14, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpouchi, M.; Moniruzzaman, A.; Russolillo, A.; Somers, J.M. Food insecurity among homeless adults with mental illness. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Hanning, R.M.; Tsuji, L.J. Prevalence and severity of household food insecurity of First Nations people living in an on-reserve, sub-Artic community within the Mushkegowuk Territory. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, M.; Béland, Y. Mode effects in the Canadian Community Health Survey: A Comparison of CAPI and CATI. In Proceedings of the American Statistical Association Meeting, Survey Research Methods; American Statistical Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Tarasuk, V. Food insecurity and participation in community food programs among low-income Toronto families. Can. J. Public Health 2009, 100, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Oleckno, W.A. Epidemiology: Concepts and Methods; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Pub: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mawani, F.N.; Gilmour, H. Validation of self-rated mental health. Health Rep. 2010, 21, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Categories | Percent | 95% CI |

| Outcome | |||

| Depressive Thoughts in the Past Month | Yes | 20.0 | 19.6–20.3 |

| Anxiety Disorders | Yes | 5.8 | 5.7–6.0 |

| Mood Disorders | Yes | 7.2 | 7.0–7.3 |

| Suicidal Thoughts in the Past Year | Yes | 19.7 | 18.7–20.7 |

| Mental Health Status | Fair/Poor | 5.3 | 5.2–5.4 |

| Exposure | |||

| Household Food Insecurity Level | Food Secure | 88.2 | 88.0–88.4 |

| Marginal Food Insecurity | 3.7 | 3.5–3.8 | |

| Moderate Food Insecurity | 6.7 | 6.5–6.9 | |

| Severe Food Insecurity | 1.4 | 1.3–1.5 | |

| Covariate | Categories | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Age | Continuous (18–64) | 42.8 | 13.5 |

| Covariate | Categories | Percent | 95% CI |

| Sex | Male | 49.1 | 49.1–49.2 |

| Female | 50.9 | 50.8–50.9 | |

| Household Composition | Unattached, living alone | 12.5 | 12.3–12.7 |

| Single living with others | 5.1 | 5.0–5.3 | |

| Couple, no kids | 25.3 | 25.0–25.5 | |

| Couple with kids <25 | 45.0 | 44.7–45.3 | |

| Lone parent, kids <25 | 6.1 | 5.9–6.3 | |

| Other/multi-family | 6.0 | 5.9–6.2 | |

| Marital Status | Common-law or Married | 65.2 | 64.9–65.4 |

| Divorced, Widowed, or Separated | 9.2 | 9.0–9.4 | |

| Single | 25.7 | 25.4–25.9 | |

| Inflation-Adjusted Income a | Low | 5.8 | 5.6–5.9 |

| Med-High | 94.2 | 94.1–94.4 | |

| Income Source | Wages & Salary | 88.9 | 88.7–89.1 |

| Social Assistance b | 9.3 | 9.2–9.5 | |

| Other c | 2.7 | 2.6–2.8 | |

| Race | White | 79.2 | 78.9–79.6 |

| Asian | 11.7 | 11.4–11.9 | |

| Indigenous | 2.6 | 2.5–2.7 | |

| Other d | 6.5 | 6.3–6.7 | |

| Education | Post-Secondary Degree | 80.5 | 80.2–80.7 |

| Some Post-Secondary | 5.4 | 5.2–5.5 | |

| High School Grad | 9.8 | 9.7–10.0 | |

| Less than High School | 4.4 | 4.2–4.5 | |

| Immigration | Immigrated ≥10 years | 15.7 | 15.5–16.0 |

| Immigrated <10 years | 7.5 | 7.3–7.7 | |

| Canadian Born | 76.7 | 76.4–77.0 | |

| Homeownership | Homeowner | 73.5 | 73.1–73.8 |

| Renter | 26.5 | 26.2–26.9 | |

| Cycle of CCHS | 3.1 | 22.2 | 22.1–22.3 |

| 2007/2008 | 25.5 | 25.4–25.6 | |

| 2009/2010 | 25.6 | 25.6–25.7 | |

| 2011/2012 | 26.6 | 26.6–26.7 | |

| Variable Category | Depressive Thoughts in the Past Month | Anxiety Disorders | Mood Disorders | Suicidal Thoughts in the Past Year | Fair/Poor Mental Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household Food Insecurity Level | |||||

| Food Secure | 17.5 (17.2, 17.9) | 4.8 (4.7, 4.9) | 5.8 (5.7, 5.9) | 16.8 (15.7, 17.8) | 4.0 (3.9, 4.1) |

| Marginally Food Insecurity | 31.1 (28.7, 33.5) | 9.9 (9.1, 10.8) | 11.4 (10.5, 12.2) | 25.6 (21.2, 30.0) | 9.2 (8.3, 10.1) |

| Moderately Food Insecurity | 39.8 (37.8,4 1.7) | 13.6 (12.8, 14.3) | 17.4 (16.6, 18.3) | 24.8 (22.0, 27.7) | 15.0 (14.2, 15.8) |

| Severely Food Insecurity | 59.3 (55.2, 63.4) | 25.4 (23.5, 27.3) | 34.2 (32.0, 36.4) | 41.0 (36.1, 45.9) | 31.1 (28.9, 33.4) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 15.1 (14.6, 15.7) | 4.1 (4.0, 4.3) | 5.0 (4.8, 5.2) | 20.9 (19.4, 22.4) | 4.8 (4.6, 5.0) |

| Female | 24.7 (24.1, 25.2) | 7.5 (7.3, 7.7) | 9.3 (9.1, 9.5) | 18.8 (17.5, 20.1) | 5.8 (5.6, 6.0) |

| Variable Category | Model 1: Depressive Thoughts in the Past Month | Model 2: Anxiety Disorders | Model 3: Mood Disorders | Model 4: Suicidal Thoughts in the Past Year | Model 5: Fair/Poor Mental Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

| Household Food Insecurity Level (food secure = ref) | |||||

| Marginal Food Insecurity | 2.3 ** (2.0, 2.8) | 2.2 ** (1.9, 2.7) | 2.3 ** (1.9, 2.7) | 1.8 * (1.3, 2.6) | 2.4 ** (2.1, 2.9) |

| Moderate Food Insecurity | 3.2 ** (2.8, 3.7) | 2.8 ** (2.5, 3.2) | 3.2 ** (2.9, 3.6) | 1.8 ** (1.4, 2.4) | 4.3 ** (3.8, 4.8) |

| Severe Food Insecurity | 8.2 ** (6.3, 10.6) | 6.3 ** (5.4, 7.3) | 8.4 ** (7.2, 9.7) | 3.0 ** (2.2, 4.1) | 11.0 ** (9.2, 13.1) |

| Sex (male = ref) | |||||

| Female | 1.9 ** (1.8, 2.0) | 1.8 ** (1.7, 1.9) | 1.9 ** (1.8, 2.0) | 0.9 * (0.7, 1.0) | 1.2 ** (1.1, 1.2) |

| Marginal * Female | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) |

| Moderate * Female | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.1) |

| Severe * Female | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.3) | 1.3 (0.9, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jessiman-Perreault, G.; McIntyre, L. Household Food Insecurity Narrows the Sex Gap in Five Adverse Mental Health Outcomes among Canadian Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030319

Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L. Household Food Insecurity Narrows the Sex Gap in Five Adverse Mental Health Outcomes among Canadian Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(3):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030319

Chicago/Turabian StyleJessiman-Perreault, Geneviève, and Lynn McIntyre. 2019. "Household Food Insecurity Narrows the Sex Gap in Five Adverse Mental Health Outcomes among Canadian Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 3: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030319

APA StyleJessiman-Perreault, G., & McIntyre, L. (2019). Household Food Insecurity Narrows the Sex Gap in Five Adverse Mental Health Outcomes among Canadian Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030319