1. Introduction

Teachers’ intervention is determinant for the integral formation of students. According to Gilar-Corbi, et al. ([

1], p. 161) “

the goal of a complete education is not only to teach technical skills, but also other skills, such as teamwork, effective communication skills, project and time management, and the ability to coordinate our emotions for that purpose.” Thus, it is difficult to consider the success of adolescents’ education process without considering it from a broad perspective and addressing the main problems faced by students. In this sense, bullying has become one of the main pitfalls to be overcome by the educational community, concerned with its prevention [

2,

3] due to its high presence in schools worldwide [

4,

5], and its devastating consequences in the affected youths’ health [

6]. A meta-analysis [

7] showing 80 international studies indicated prevalence levels of 34.5 and 36% for bullying perpetration and bullying victimization, respectively. Available data on bullying in Spain for adolescents aged 12 to 18 in Compulsory Secondary Education show that between 3 and 5% of the students are victims of severe bullying, whereas between 15 and 20% suffer moderate bullying [

8]. Although “

for many years, schools in Spain have maintained a passive stance toward teen bullying, with the understanding that the role of teachers was to teach, rather than participate in mediation in these cases” ([

8], p. 594), considering the prevalence data and some cases of great social impact that have ended in suicide of students who suffered bullying in Spain, there is a currently growing concern to determine what teachers and other school staff can do to combat bullying.

About forty years of research on this topic have advanced our knowledge of the characteristics that define this particular type of violence, as well as of some of the predictor variables of these behaviors. However, further analysis of the relationships between the variables involved seems necessary to develop more effective strategies that increase the effectiveness of intervention programs [

9]. The inclusion of new or understudied variables in the predictive models, as well as methodological approaches that reveal hidden relationships between the antecedents of bullying, could help achieve this objective. This paper aims to fill some gaps in the literature of the study of the hidden relationships between variables, including the study of resilience as an antecedent, as some researchers demand [

10]. In addition, considering the responsibility given to the field of physical education (PE) in Spain for education in values and development of social and citizens’ competence [

11], this work seeks to contribute to understanding the role of PE teachers regarding bullying.

Bullying is any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. It implies the intention of causing physical, psychological, social or educational harm [

12]. Thus, victims can be beaten, insulted, threatened, socially excluded, or suffer damage to their property, they feel helpless in the presence of other peers, known as spectators, who adopt multiple roles depending on their attitude toward the event of intimidation [

13] and who become very important in the process [

14].

Personal factors such as empathy, self-esteem, moral disengagement, depression, and anxiety, among others, have been indicated as antecedents of bullying and victimization behaviors [

15]. By contrast, few works in the educational field have included the concept of resilience as a personal factor related to bullying [

16].

Resilience is defined as the ability to recover and maintain adaptive behavior after an initial incapacity in the face of a stressful event. Rather than invulnerability to stress, it is the ability to recover from the effects of negative events [

17]. Some authors distinguish two components of resilience: resilience to destruction, that is, the ability to protect one’s own integrity under pressure, and, beyond resistance, the ability to forge a positive life behavior despite difficult circumstances [

18]. It seems that resilience is not a characteristic that some people possess and others do not possess at all [

16] but rather, it is an internal characteristic that can be reinforced or weakened by environmental factors [

19,

20].

The sources that contribute to the level of resilience are often grouped into two categories: external and internal [

21]. The internal elements involve self-esteem, self-control, self-efficacy, and an internal locus of control [

22], whereas the external elements producing resilience include, although they are not the only ones, social support and supportive environments, positive peer relationships, and a sense of belonging to a group [

23]. The results of Montero-Carretero, and Cervelló [

24] in a study with Spanish adolescents between the ages of 11 and 15, showed that the possibility of reporting and asking teachers for help, as well as the connection with the school, positively predicted resilience and this, in turn, negatively predicted victimization.

Regarding the relationship between resilience and bullying, few studies have analyzed the mediation effect of resilience on the victimization process. The work performed by Navarro, et al. [

25] with adolescent students found that resilience had a moderating effect on victimization by cyberbullying, such that it was shown to be a “protector” against victimization, in line with the results of another study that analyzed the predictive power of resilience on cyberbullying [

26] in 377 Turkish students aged 15 to 19, in which a simple regression analysis revealed that resilience negatively predicted cyberbullying perpetration and cybervictimization. The results of Hinduja and Patchin [

16], in another work performed with American students aged 12 to 17, indicated resilience as a powerful protective factor, both to prevent experiences of intimidation and to mitigate their effect, in line with the claims of other authors [

8] who already suggested the possible protective nature of resilience in such situations, or as in the work of Moore and Woodcock [

27], in which students with poorer resilience were more prone to engage in bullying behaviors as well as to become victims. Another study in Israel [

28] analyzed the impact of cultural settings and individual protective attributes on peer bullying and victimization in school. This study, involving 112 Jewish and 55 Bedouin Arab students aged 10 to 11, considered self-esteem, a sense of autonomy, emotion regulation, and individual resilience as protective attributes, and the authors concluded that resilience could play a more important role in predicting adolescent violence in school than other personality attributes. In the study of the relationships between resilience and bullying, the work of Tobias and Chapanar [

29] proposed another perspective, analyzing how cyberbullying experiences can influence student resilience. The authors concluded that, whereas these cyberbullying events can be very traumatic for students, they sometimes produce increases in some resilience factors. This is easier as long as other social factors contribute to overcoming the events from appropriate climates.

On the other hand, the literature has described the importance of teacher instructional practices when generating positive school climates, characterized, among other things, by developing environments of respect and security with a high quality of social relations [

30,

31]. In this regard, some spaces within the school have special characteristics that could be more conducive to the development of bullying behaviors. Such is the case of the PE classroom, where the public demonstration of students’ motor skills is demanded, and where schoolchildren’s physical characteristics emerge in a particular way, and these are some of the main causes of bullying [

32]. In this area, there is growing interest to study how the teacher’s interpersonal style will have a psychological impact on the students’ experiences [

33]. For years, researchers concerned about pedagogy in PE have tried to discover the benefits of different teaching styles [

34]. A review article that referred to the Spectrum of Teaching Styles [

35] to elucidate the advantages of the different teaching styles concluded that “

all styles are valid pending the objectives of the experience, and each contributes to the overall educational process” ([

36], p. 202), although some works showed benefits in the social and moral domain of the styles that gave the student greater autonomy versus more directive styles [

37,

38,

39]. The results of another review that focused on analyzing the current situation of PE-student-centered styles and methodologies at pre-university levels showed that teachers mostly use traditional or teacher-centered styles [

40], although the Spanish education system indicates the need to implement student-centered styles for competence acquisition. The authors highlight the important contributions of psychology applied to teaching when justifying the change towards student-centered styles, especially from the self-determination theory (SDT).

The SDT [

41,

42] has been one of the main theoretical frameworks for explaining the behaviors of human beings based on their motivations, serving as a reference for analyzing teachers’ interpersonal styles. From this theory, and within the school context, teachers are considered very decisive social agents for the students to satisfy their three basic psychological needs (BPNs) of autonomy (acting freely without imposition), competence (feeling effective) and relatedness (connection with other people), which leads to more self-determined motivations that result in more adaptive consequences. Reeve [

43] stated that, in PE classes, the most prominent source of support for students’ needs is the teacher’s motivating style. From this theoretical framework, the most studied teaching styles have been the autonomy support (AS) style and the controlling style (CS).

Referring to AS, Roth, et al. indicate that “

the contexts of support for autonomy involve the recognition of the child’s feelings, the adoption of the child’s perspective, justification, the possibility of choice, and the minimization of pressure” ([

44], p. 656). For their part, Guay and Vallerand defined the teacher’s AS as “

the degree to which people use techniques that encourage choice and participation in school activities” ([

45], p. 215). Following this approach, Tilga, et al. [

46] propose that autonomy-supportive behavior could be characterized by three dimensions: organizational, procedural, and cognitive. Thus, organizational autonomy support encourages students to take possession of the environment and could include teaching behaviors that offer students opportunities to choose the teaching methods and where to perform an exercise. Procedural autonomy support encourages students to become the owners of the way activities are performed and could include teaching behaviors such as offering students the choice of how to present homework. Cognitive autonomy support encourages student learning and could include teaching behaviors such as asking the students to justify and defend their point of view, or to seek solutions to a problem.

In particular, and from the conceptual model of the self-determination theory [

41,

42], research on the PE teachers’ interpersonal styles supporting student autonomy has shown that such support has a positive effect on self-determined motivation in PE students, positively influencing affective and behavioral relationships in class [

46,

47]. Other studies have shown positive relationships between AS and prosocial behavior [

48], and a greater intention to be physically active [

49]. In a study conducted with students in PE classes, Lam, et al. [

50] showed that AS negatively predicted bullying behaviors through satisfaction of the need for relatedness. Roth, et al. [

44] observed an inverse relationship between the AS perceived by students and bullying behavior, and they suggest that schools should establish AS teacher styles, and that researchers should continue to analyze the effect of this interpersonal teacher style on bullying behaviors., a recent study in South Korea [

51] analyzed the effects of a training program, called Autonomy-Supportive Intervention Program (ASIP), aimed at increasing the autonomy-support of PE teachers from the SDT framework. Among the different contents of the program, PE teachers learned to implement six recommended AS instructional behaviors, including taking the students’ perspective, vitalizing inner motivational resources, using informational language, providing explanatory rationales, acknowledging and accepting negative affect, and displaying patience. ASIP participation increased teachers’ AS and students’ need satisfaction and prosocial behavior, and it decreased teachers’ control and students’ need thwarting, antisocial behavior, and positive attitude toward cheating. Systematic review of the effects of AS-based programs in PE [

52] showed positive effects of AS on the satisfaction of students’ BPNs and self-determined motivations, and concluded by emphasizing the importance of PE teachers developing this interpersonal style to encourage physical exercise outside the school and to avoid a number of negative and maladaptive behaviors of students in the PE classroom.

On the other hand, CS is defined by authoritarian attitudes of the teacher, who ignores the students’ preferences and tries to impose a specific way of thinking, feeling, and behaving, using pressure [

43,

53]. Teachers who teach with this style sometimes resort to shouting, threatening, or punishing to gain control of the students, and at other times, they try to provoke feelings of guilt or embarrassment in the student, withdrawing their attention or interest and expressing disappointment when their expectations are not met [

54].

In contrast to the AS, teachers’ CS has shown relationships with lower levels of perceived satisfaction and student commitment [

55], an increase in levels of physiological stress markers, such as cortisol [

56], and increases in students’ anger and anxiety [

57]. For instance, teacher controlling style, primarily through the intimidation factor, significantly predicted bullying and anger in a sample of 602 adolescent students [

58].

Both resilience and the teacher’s interpersonal style seem to be related to the emergence and regulation of bullying behaviors. However, the interaction between these factors and the extent to which the PE teacher’s interpersonal style can predict such behaviors remain to be studied. Therefore, the analysis of the aforementioned interaction was the main objective of our work.

Some studies have highlighted the need to develop measuring instruments that can collect, in the field of PE, both the AS and the CS style of the PE teacher. Thus, in the work of Tilga, et al. [

59], the need to measure the different components of autonomy support has been highlighted, distinguishing between cognitive, organizational, or procedural autonomy. That is why validation of these instruments in new languages and cultures is necessary. There is also a need to develop or adapt instruments for the measurement of resilience that are suitable for PE. For the measurement of resilience in Spanish, the existing measuring instruments [

25] had never been subjected to a confirmatory factorial analysis, so it is necessary to validate them. That is why, as a secondary objective, the Spanish versions of the measuring instruments of the studied variables will be validated, so that they can be useful for the evaluation of the teacher’s interpersonal style and of student resilience.

Our working hypotheses are:

- (1)

PE teacher’s interpersonal AS style will be positively related to and will positively predict resilience, considering the characteristics of an interpersonal style based on AS [

45,

46] and external sources that facilitate the development of resilience, such as social support and supportive environments, positive peer relationships, and a sense of belonging to a group [

21,

23]. In turn, PE teacher’s interpersonal AS style will negatively predict bullying behaviors, as was the case in previous studies [

44,

49,

50] in which this interpersonal style negatively predicted antisocial behavior [

51].

- (2)

The CS will be positively related to and will positively predict bullying behaviors as in a study with Estonian students between 12 and 16 years [

58].

- (3)

Resilience will be negatively related to and will negatively predict victimization as in previous studies on traditional bullying [

24,

25,

27,

28] and cyberbullying [

26].

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to analyze the relationships between the PE teacher’s interpersonal style, students’ resilience, bullying, and victimization. Whereas some studies have shown the relationship between PE teachers’ interpersonal style with bullying and victimization, and some others have described negative relationships between resilience and bullying and victimization, we know of no studies to date that have analyzed the role of resilience in relation to the interpersonal style of the teacher of any educational subject and bullying. Therefore, the analysis of all the variables under study in our work makes it a pilot study, which could be considered a relevant contribution. In addition, the study of these variables in the specific context of PE may be of particular interest when considering the responsibility that the Spanish education system gives to this subject on values education and the development of social and citizen competence [

11].

In favor of our first hypothesis, AS in PE classes positively predicted students’ resilience. These results give the PE teacher the opportunity to contribute to the promotion of more resilient students, generating supportive climates, fostering positive peer relationships, and increasing the feeling of belonging to the group, which, as suggested by other authors, is critical for the development of resilience [

21,

23]. Also in favor of the first hypothesis, the AS provided by the PE teacher reduced bullying, as previously occurred in [

50] and just as it did with 13- and 14-year-old Israelis, where the AS provided by teachers from other knowledge areas was decisive in the internalization of pro-social values, to the detriment of bullying behavior [

44]. According to these authors, programs that reduce the frequency of bullying predominantly through rigorous control of the setting are only effective while such control remains, but cease to be so when control is not so clearly manifest. On the other hand, the advantage of programs which, through AS, promote the identification and integration of pro-social values and behaviors is that the effects of the program are maintained over time and everywhere. This seems to be because young people decrease their aggressions due to their own appraisal of such behaviors, and not because they feel they are in a setting where such behaviors are will be punished. Readers are reminded that one of the challenges that program creators face when they design programs to prevent bullying is to make their effects last over time [

10]. In addition, the results of this study showed that CS favored more student bullying, confirming the second hypothesis, and these results are similar to the findings of Hein, et al. [

58].

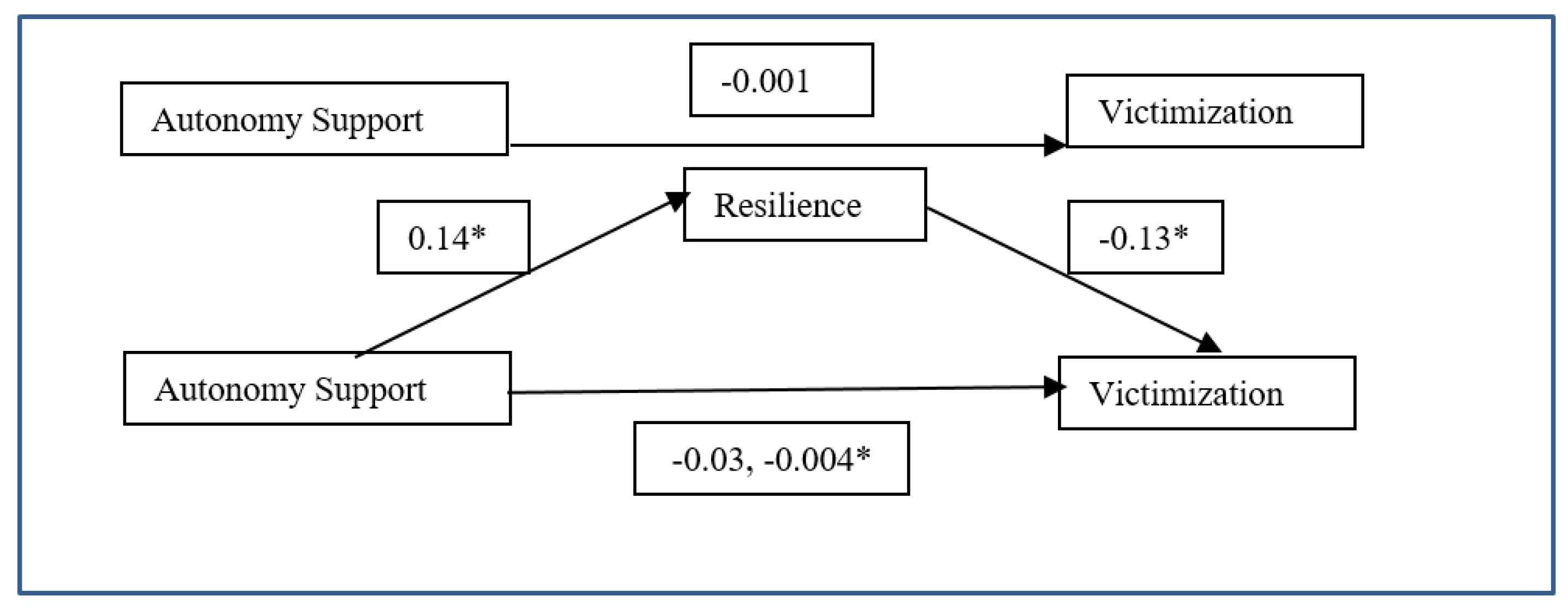

On the other hand, in relation with the predictive nature of PE teachers’ interpersonal styles on the complex phenomenon of bullying, we expected that both AS and CS would predict victimization, as occurred with bullying. However, only the CS, together with resilience (the former positively and the latter negatively) predicted victimization. Contrary to our expectations, AS did not do so directly. It has already been shown that CS within the educational realm have very negative maladaptive consequences, such as anger, anxiety, perceived low satisfaction, or lack of commitment [

55,

56,

57]. A review [

52], whose objective was to analyze the effects of interpersonal styles in PE, showed that CS was associated with high levels of amotivation [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78]. Since, contrary to our initial hypotheses, AS did not appear to be a significant predictor of victimization, we decided to study in more depth the relationships of these constructs and, through mediation analysis, seek possible underlying relationships. In this analysis, AS predicted resilience and this predicted victimization, in favor of the third hypothesis, in which this predictive power of resilience on victimization was expected. This approach, through mediation analysis, was decisive in understanding the influence of AS on victimization, mediated by resilience. In view of these results, it would be interesting to continue to study the role of resilience in the face of victimization behaviors, and, as mentioned, to make young people resistant to stressful situations and to help them generate adaptive responses that will make them stronger after these events. Zych, et al. [

10] state that future work should shed light on mechanisms that build resilience, and suggest that intervention programs aimed at preventing bullying should incorporate strategies to increase social and emotional competence, and recommend changing the educational curriculum to address these contents. In the same direction Beltrán-Catalán, et al. [

79] recommend further research on how emotional intelligence can help in the face of victimization. In fact, the results of Casas, et al. [

80] identified as predictors of victimization factors such as the low ability to distinguish one’s emotions at any given time and some people’s low perception of their ability to replace their negative emotions with more positive ones. Considering these recommendations, the relationships of resilience with school engagement [

81], and our results, we propose that formulas be included in the subject of PE to make students more resilient. We note that the scenario presented by this subject could be an ideal environment to detect cases of bullying early on so as to intervene in prevention [

32]. Some authors have already shown that sport and physical activity can be an ideal means to build personal resilience through the improvement of physical self-concept [

82], so damaged in victims of bullying [

83].

In this direction, and considering the findings of Del Rey, et al. [

84] that point to the strong effect that teaching management has on emotions and the emergence of bullying or victimization behaviors, it seems increasingly advisable for teachers to train and apply styles of AS [

85], avoiding CS [

86]. Given the works that indicate the need for more evidence to demonstrate the benefits of student-centered teaching styles over more traditional and directive ones, the results of this study seem to support those of other authors who have previously shown better results in the social and moral levels when using these styles that facilitate students’ choice [

37,

38,

39]. Thus, considering the results of Zapatero [

40], who stated that PE teachers currently exercise predominantly traditional teacher-centered methodologies, we emphasize the importance of PE teachers’ being trained in styles that promote autonomy. These specific trainings have provided good results in previous programs [

51], achieving increased teachers’ AS and students’ need satisfaction and prosocial behavior, and they decreased teachers’ control and students’ need thwarting and antisocial behavior.

Thus, from a practical point of view, and in view of our results, it would be very interesting if, among other things, PE teachers could ask students for feedback on their tastes and preferences concerning the exercises or games that serve to achieve specific objectives, taking this into account when planning classes. They could also give students a choice of the classmates with whom to form groups to perform tasks, how to perform some of the tasks, the time they want to spend on each one, the order in which they perform them, the material with which to perform them, or the location within the available school spaces where they do them. It may even be advisable to assign responsibility to the students in the evaluation process, as suggested by Moreno-Murcia, et al. [

87]. The fact that students perceive that the teacher gives them the opportunity to choose within their classes does not clash with the achievement of the goals set by the teacher, provided that the teacher has sufficient training in the subject taught as well as in teaching methodologies that allow the development of an interpersonal style far from the more traditional, controlling, and dictatorial styles within the classroom [

88]. In addition, motor games within the PE class offer a multitude of possibilities to manage conflict in a safe and regulated environment. With the teacher’s help, students can establish a relationship between the challenges and conflicts of games during the classes and those they encounter in everyday life in relation to bullying, contributing to the development of resilience in students for whom these challenges imply some stress and self-improvement. On the other hand, cooperative games, in which the teacher proposes the achievement of joint objectives to groups of students, could be ideal for improving relations among them, taking into account the benefits of cooperative learning [

89].

In this sense, and from the subject of PE, the opposing positions among students participating in direct opposition games, where the achievement of the objective by some of them implies dismantling the opponents’ strategies, imposing their own potentials (fighting for a space, tug of war, controlling the opponent’s body according to sports rules such as judo, trying to score in two-on-one situations, etc.), can be the ideal means for students to train in the control of their emotions by confronting the controlled encounters that may arise from such situations within the classroom [

90].

Thus, we consider that the PE teacher, showing his/her responsibility as a teacher and through styles with AS, has the opportunity to contribute to the development of the students’ personal resilience and to the prevention of bullying behaviors through a multitude of proposals, ranging from exercises and games where young people collaborate to overcome challenges, to those that require maximum opposition between them.

Regarding the second objective of the study, the statistical analyses carried out have shown that the Spanish versions of the Multidimensional Perceived Autonomy Support Scale for Physical Education (MD-PASS-PE) by Tilga, et al. [

46] and of the Controlling Style factor of the Empowerment in Sport Questionnaire (EDMCQ-C) by Appleton, et al. [

60], and the Spanish version of the 10-item Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) by Connor and Davidson [

61] are robust to measure the intended constructs and are consistent in their relationship with the other constructs analyzed, so they can be used in PE. As in the work of Tilga, et al. [

59], the questionnaire is invariant (in this case, by age and group), obtaining fit indices very similar to ours.