Analysis of Necessary Support in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

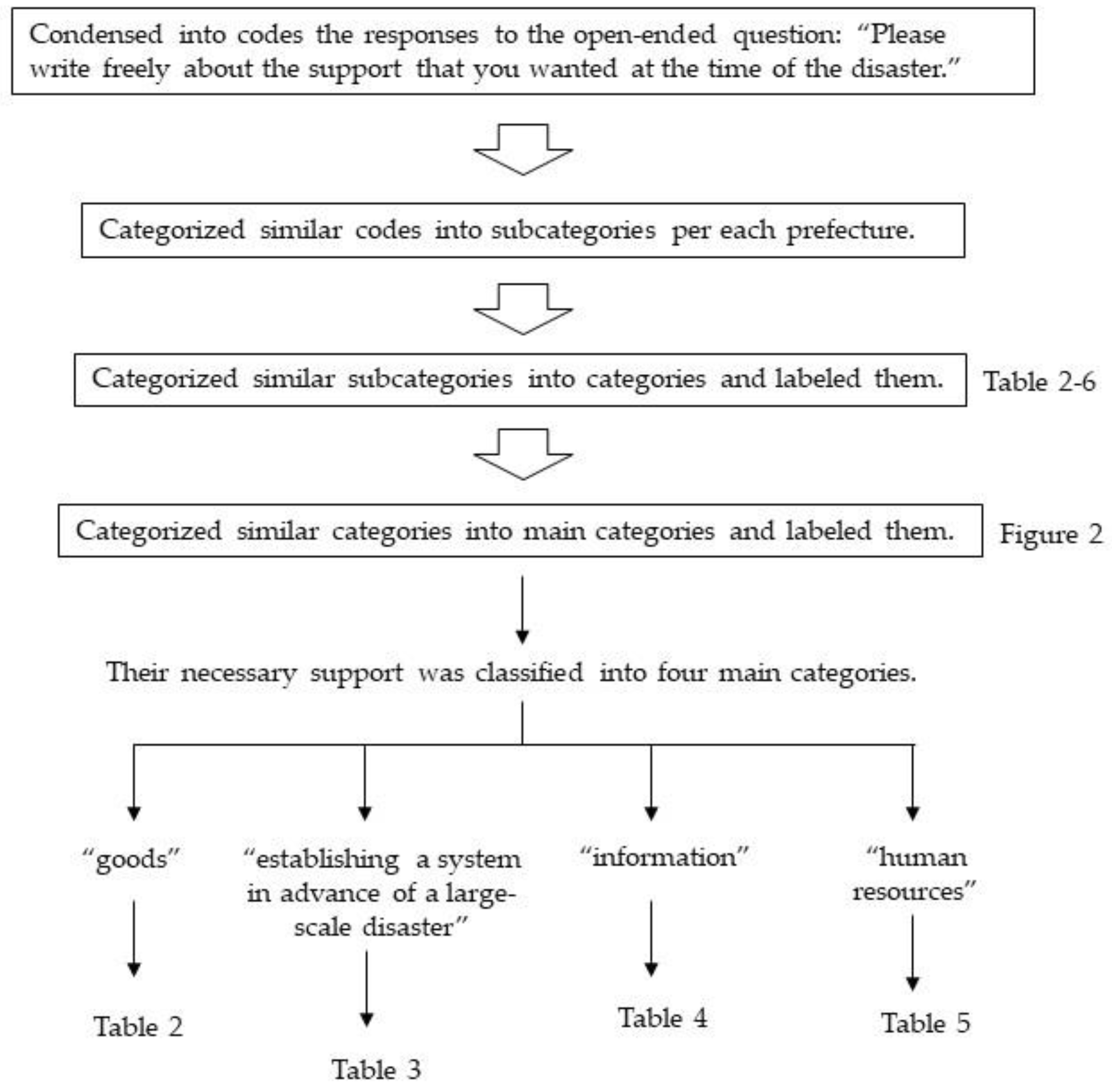

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. The Main Category: “Goods”

3.2. The Main Category: “Establishing a System in Advance of a Large-Scale Disaster”

3.3. The Main Category: “Information”

3.4. The Main Category: “Human Resources”

3.5. The Main Category: “Others”

4. Discussion

4.1. The Main Category: “Goods”

4.2. The Main Category: “Establishing a System in Advance of a Large-Scale Disaster”

4.3. The Main Category: “Information”

4.4. The Main Category: “Human Resources”

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AghaKouchak, A.; Huning, L.S.; Chiang, F.; Sadegh, M.; Vahedifard, F.; Mazdiyasni, O.; Moftakhari, H.; Mallakpour, I. How do natural hazards cascade to cause disasters? Nature 2018, 561, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirai, K.; Okuda, T.; Masuda, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Tsuzukida, Y.; Takao, F. Food Intake and Diet Considerations among Victims Living in Evacuation Centers after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. J. Integr. Study Diet. Habits 1998, 9, 28–35. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, N.; Isobe, S.; Watanabe, S.; Ishigami, K.; Yoshita, K.; Yoshiike, N.; Murayama, N. Changes in Access to Food and the Frequency of Food Consumption before and after the Niigata Chuetsu Earthquake: Comparison between Households in Temporary Housing and Disaster-stricken Housing. J. Jpn. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 53, 340–348. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Hoshi, Y.; Onodera, K.; Mizuno, S.; Sako, K. What factors were important for dietary improvement in emergency shelters after the Great East Japan Earthquake? Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fire and Disaster Management Agency. Available online: https://www.fdma.go.jp/disaster/higashinihon/items/159.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2020). (In Japanese).

- Harada, M.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Takizawa, A.; Hidemi, T.; Oka, J. Improving Nutrient Balance by Providing Main and Side Dishes in Emergency Shelters after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. J. Disast. Med. 2017, 22, 17–23. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Purba, M.B. Nutrition and earthquakes: Experience and recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S.; Sudo, N.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Okazaki, N.; Nabeshima, K.; Kanatani, Y.; Okumura, T.; Shimoura, Y. An Analysis of Support Activities by Registered Dietitians and Dietitians Dispatched by the Japan Dietetic Association after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. Jpn. Diet. Assoc. 2015, 58, 111–120. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, H.; Sudo, N.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Kanatani, Y.; Shimoura, Y. Analysis of “what I thought today” reported by dietitians dispatched by the Japan Dietetic Association to the affected areas by the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. Jpn. Diet. Assoc. 2015, 58, 35–44. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Harada, M.; Takizawa, A.; Oka, J.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N. The effects of changes in the meal providing system on emergency shelter menus following the Great East Japan Earthquake. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2017, 64, 547–555. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Hirono, R.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Takizawa, A.; Sudo, N.; Shimoura, Y.; Sako, K. Analysis of the Effective or Problematic Points of Nutrition Support Activities by Dietitians Dispatched to Areas Affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. Jpn. Disaster Food Soc. 2016, 3, 19–24. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014; pp. 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Kondo, A.; Harada, M.; Ueda, S.; Sudo, N.; Kanatani, Y.; Shimoura, Y.; Nakakuki, K. Analysis of an Oral Health Report from Dietitians Dispatched to the Areas Affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Jpn. J. Dysphagia. Rehabil. 2017, 21, 191–199. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, K.; Sudo, N.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Yamamura, K.; Yamashita, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Shimoura, Y.; Komatsu, T. Nationwide survey on local governments’ current preparedness for food and nutrition assistance during natural disasters: Regional disaster prevention plan and stockpiles. J. Jpn. Diet. Assoc. 2015, 58, 517–526. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sudo, N.; Urakawa, M.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Yamada, K.; Shimoura, Y.; Yoshiike, N. Local Governments’ Disaster Emergency Communication and Information Collection for Nutrition Assistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, Y. Logistics for Disaster Relief Supply. RKU Logist. Rev. 2011, 56, 11–15. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Yuan, Y. Emergency Logistics in a Large-Scale Disaster Context: Achievements and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, A.; Tanigawa, K.; Ohtsuru, A.; Yabe, H.; Maeda, M.; Shigemura, J.; Ohira, T.; Tominaga, T.; Akashi, M.; Hirohashi, N.; et al. Health effects of radiation and other health problems in the aftermath of nuclear accidents, with an emphasis on Fukushima. Lancet 2015, 386, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, J.; Terayama, T.; Kurosawa, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Toda, H.; Nagamine, M.; Yoshino, A. Mental health consequences for survivors of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster: A systematic review. Part 1: Psychological Consequences. CNS Spectr. 2020, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka-Maeda, K.; Kuroda, M.; Togari, T. Difficulties of fathers whose families evacuated voluntarily after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Nurs. Health. Sci. 2018, 20, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, N.; Ogino, H. Food safety regulations: What we learned from the Fukushima nuclear accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2012, 111, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozue, M.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Sarukura, N.; Sako, K.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N. Stockpiles and food availability in feeding facilities after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N.; Harada, M. Analysis of Mass Feeding for Evacuees in Emergency Shelters after the Great East Japan Earthquake: Outside Support from Self-defense Forces, Volunteers, and Dietitians. J. Jpn. Disaster Food Soc. 2017, 5, 1–5. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Toh, N. State of current status and issues for visiting nutritional guidance for home-bound patients: The internet based attitude survey of nutritional counselling for home-bound patient by 450 dieticians and management dieticians. J. Integr. Study Diet. Habits 2017, 28, 159–168. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Surianto, S.; Alim, S.; Nindrea, R.D.; Trisnantoro, L. Regional Policy for Disaster Risk Management in Developing Countries Within the Sendai Framework: A Systematic Review. Open Access Maced. J. Med Sci. 2019, 7, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 6 | (1.8) | |

| Female | 298 | (89.8) | |

| Unknown | 28 | (8.4) | |

| Age | |||

| 20–29 years | 43 | (13.0) | |

| 30–39 years | 90 | (27.1) | |

| 40–49 years | 86 | (25.9) | |

| 50–59 years | 81 | (24.4) | |

| 60–69 years | 26 | (7.8) | |

| 70–79 years | 3 | (0.9) | |

| Unknown | 3 | (0.9) | |

| Occupation category | |||

| Welfare facility | 102 | (30.7) | |

| Hospital | 94 | (28.3) | |

| Government | 44 | (13.3) | |

| School | 25 | (7.5) | |

| Education/Research | 15 | (4.5) | |

| Community activities | 15 | (4.5) | |

| Feeding facility | 6 | (1.8) | |

| Other dietitian positions | 9 | (2.7) | |

| Other occupations | 6 | (1.8) | |

| No work | 14 | (4.2) | |

| Unknown | 2 | (0.6) | |

| Damage of workplace | |||

| None | 99 | (29.8) | |

| Partially damaged | 181 | (54.5) | |

| Completely destroyed | 9 | (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 43 | (13.0) | |

| Category (Number of Codes) | Subcategory (Number of Codes) | Number of Codes and Specific Code Examples (Per Each Prefecture) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwate Prefecture | Miyagi Prefecture | Fukushima Prefecture | ||

| Food (65) | Food (25) | 6 codes -Dietary support for living rather than nutritional counseling was important in the situation without food. -Preparing stockpile food for staff. | 12 codes -Food did not reach us until day 7, and I was at a loss. -Ingredients of rice ball | 7 codes -Food shortages occurred in disaster areas and areas where survivors were accepted. -There was a limit to the number of ingredients I could buy. |

| Vegetables (10) | 1 code -Vegetables | 4 codes -Vegetables | 5 codes -Bread was provided as a relief supply, but survivors were not very pleased. Vegetables were few, and volunteers brought them. | |

| Food to supplement nutrients (5) (e.g., dietary supplements) | 3 codes -The dietary supplement arrival was late. -Something to supplement nutrition-deficient nutrients such as vitamins. | 1 code -Even if relief supplies arrived, it was only bread or noodles. Micronutrients were not supplied. | 1 code -There were a lot of rice balls and bread at emergency shelters. Many survivors seemed to be constipated. | |

| Protein source (5) | – | 1 code -Protein source | 4 codes -Perishable foods (protein sources such as fish and meat) -Retort food to be protein sources -Milk | |

| Rice/Bread (4) | 2 codes -Rice/Bread | – | 2 codes -Rice -Bread | |

| Mass feeding for survivors (4) | – | 2 codes -A high frequency of mass feeding for survivors was better than supplying the supplement. -Support for “Hot meal mass feeding for survivors” | 2 codes -Mass feeding for survivors (this differs among respective emergency shelters) | |

| Cookless food (4) | 2 codes -PET bottle of Japanese tea | 1 code -Ready-to-eat food | 1 code -Cookless food | |

| Canned food (2) | 2 codes -Canned food | – | – | |

| Seasoning (2) | 1 code -Salt, soy sauce, miso, and sugar | – | 1 code -Spices such as ginger, garlic, or green onion | |

| Luxury food (2) | 1 code -Luxury food such as coffee | – | 1 code -Something to drink (milk, Yakult, or others) | |

| Retort pouch food (1) | 1 code -Retort pouch food | – | – | |

| Food with long storage period (1) | – | 1 code -Food with long storage period | – | |

| Gasoline (59) | Gasoline (40) | 14 codes -It was inconvenient because the gasoline shortage continued and I could not use my car. | 9 codes -Gasoline | 17 codes -There was a shortage of gasoline in the disaster areas and the areas that accepted survivors. -Gasoline was the most necessary because it was an area where I could not move around without a car. |

| Gasoline for commuting (9) | 2 codes -There were times when I could not go to work because gasoline was running short. | 1 code -Gasoline for commuting | 6 codes -Because of a gasoline shortage, it was difficult to secure our staff. I desired an oil tank. | |

| Gasoline for manufacturers to transport goods (6) | 5 codes -I did not receive deliveries due to a gasoline shortage. -The stoppage of distribution due to a gasoline shortage caused confusion of information. | – | 1 code -Because of a gasoline shortage, there were approximately three companies that were unable to deliver. | |

| Gasoline to go shopping/to go pick up goods(4) | – | 2 codes -Even if there were relief supplies, I had no way to go there (gasoline). -In order to go pick up foods or relief supplies, it would be helpful if arrangement to get gasoline was a priority. | 2 codes -Gasoline to go shopping | |

| Special diet(45) | Food for a person having difficulty in chewing/swallowing (15) | 7 codes -It was difficult to deal with forms of food other than regular meals (soft, mixed, or minced) because the machine could not be used due to blackout. -Rice porridge | 4 codes -High-calorie meals in a facility for the elderly | 4 codes -Food for persons with difficulty swallowing (because there was a shortage, we provided less quantity). -We alternated shifting from concentrated liquid diets to medicine. |

| Concentrated liquid diet (14) | 7 codes -Enteral nutrition (concentrated liquid diet) was in short supply about 1 month after the earthquake, but there was no support for it. -Distribution of concentrated liquid diet was reduced, so it was not certain when and how many would be delivered. | 4 codes -Jelly for hydration in a facility for the elderly | 3 codes -Concentrated liquid diet | |

| Fortified food (7) | 2 codes -Fortified food | 2 codes -Fortified food | 3 codes -Fortified food | |

| Food for infants (4) | 4 codes - Milk powder -Infant food in the early phase after the disaster -Water for infant in the early phase after the disaster | – | – | |

| Hypoallergenic food (3) | – | 1 code -My 1-year-old daughter has an egg allergy, so I was at a loss for her diet. I was afraid to eat the meal to be distributed and was avoiding it. | 2 codes -Initially, we could not be deal with survivors with meal problems (e.g., food allergy). | |

| Food for patients (2) | – | 1 code -Low-salt diet | 1 code -There were few supplies that could be provided as fortified food to people with kidney disease, heart disease, liver disease, and diabetes. | |

| Water (39) | Water/Water truck (30) | 8 codes -Procurement of water was difficult. A water truck came on day 4. Still, staff went to draw water from the purification plant. | 8 codes -Permanent water truck -I got in the line for the water truck because I had little water stocked. But I had a hard time carrying 2 L of water per person. | 14 codes -We had to secure water ourselves and did not receive water supply assistance. -To procure water, facility staff had to leave to procure water several times a day. |

| Drinking water/Water for the meal (4) | – | 2 codes -Drinking water -Water for the meal | 2 codes -Drinking water or oral rehydration solution such as OS-1 (Dehydration did not occur because it was in winter, but it would have been serious if it was in summer.) | |

| Cleaning water (2) | – | 2 codes -Cleaning water except for drinking water -It was difficult to secure water, so it was a challenge to wash dishes and cooking tools. | – | |

| Water for toilet (2) | – | – | 2 codes -A limit was set to water in the toilet. Considering sanitation, we needed water support. | |

| Water for bath (1) | – | – | 1 code -I could not take a bath because water was not coming out at my house. | |

| Sanitation (18) | Disposable tableware and cling film (14) | 2 codes -Disposable tableware, cling film and polyethylene bags | 10 codes -I prepared disposable tableware, but it was an issue because disposable dishes were running out quickly due to water failure. | 2 codes -Disposable tableware/cling wrap |

| Hygiene (2) | 1 code -Hygiene | 1 code -Hygiene | – | |

| Portable toilet/Diapers (2) | 1 code - Diapers | 1 code -Portable toilet | – | |

| Weatherization (17) | Kerosene (7) | 6 codes -Kerosene (Because it was cold.) | – | 1 code -Kerosene |

| Blanket/Bedding/Clothes (4) | 1 code -Blanket | 3 codes -Bedding (Especially a mattress. I slept directly on the floor, and I thought that my back would hurt and it would cause bedsores.) -Clothes | – | |

| Heat source (3) | – | 3 codes -Heat source | – | |

| Heater (2) | 1 code -Heater (1) | – | 1 code -Heater and fuel for emergency | |

| Stove (1) | – | 1 code -Kerosene stove | – | |

| Cooking environment (16) | Gas (7) | 1 code -Gas cylinder for heating | 5 codes -Measures to secure heating source (especially necessary for cooking) | 1 code -Support of gas |

| Gas stove (5) | 2 codes -Gas stove | 1 code -I wanted a gas stove that can use propane gas because the heat source was insufficient. | 2 codes -I wanted a cooking stove because I was not able to use gas. | |

| Cooking equipment/Cooking tool (4) | – | 1 code -Cooking tool | 3 codes -Cooking equipment -Refrigerator | |

| Electricity (16) | Electricity/Electric power (11) | 4 codes -Because home appliances are all-electric, I could not cook, wash, and disinfect during a blackout. So, I was concerned about food poisoning. | 6 codes -Even if information is obtained on the Internet, printing is impossible (electricity, paper, and machine). -Electric power for using cooking tools | 1 code -Electricity/Electric power |

| Battery (3) | 1 code -Generator (including battery worked by hand) | 2 codes -Battery | – | |

| Lighting (1) | – | 1 code -Lighting | – | |

| Candle (1) | 1 code -Lighting (candle) | – | – | |

| Supplies (9) | Supplies from the government (5) | – | – | 5 codes -Supplies from the government |

| Supplies (4) | – | 2 codes -Supplies | 2 codes -I desired much support from Western Japan. | |

| Goods shortage due to the nuclear accident (9) | Food shortage due to the nuclear accident (3) | – | – | 3 codes -Because of a rumor, it was awkward that I could not have food delivered (concentrated liquid diet) in Fukushima. |

| Supply shortage due to the nuclear accident (3) | – | 1 code -Because our facility was 20~30 km from the nuclear power plant, supplies were not distributed. | 2 codes -Supply shortage due to the nuclear accident | |

| Safe water due to radioactive contamination (2) | – | – | 2 codes -As water was contaminated with radioactivity, water became increasingly precious. Water was needed for dialysis as well as for cooking. | |

| Gasoline shortage due to the nuclear accident (1) | – | – | 1 code -Gasoline shortage due to the nuclear accident | |

| Others (4) | Daily commodities/Concerning housing (2) | 1 code -Daily commodities/Concerning housing | 1 code -Earthquake resisting device is necessary. | – |

| Communication equipment that can be used even in emergency (1) | – | – | 1 code -Communication equipment that can be used even in emergency | |

| Money (1) | – | – | 1 code -Money to buy what I need for cooking other than relief supplies. | |

| Category (Number of Codes) | Subcategory (Number of Codes) | Number of Codes and Specific Code Examples (Per Each Prefecture) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwate Prefecture | Miyagi Prefecture | Fukushima Prefecture | ||

| A system and preparation for distributing relief supplies (36) | A system for distributing relief supplies in a fair and appropriate quantity and timing (34) | 4 codes -A system for distributing relief supplies in a fair and appropriate quantity and timing | 14 codes -Even if we were able to harvest vegetables, etc., we could not open the market and could not adjust our distribution. | 16 codes -My desired goods could not be obtained as I expected (there were few vegetables, and there were many processed foods that were not versatile foods). |

| Stockpile (2) | 1 code -Stockpile | 1 code -Stockpile | – | |

| Creating a system for cooperation and communication in a disaster (28) | Creating a system for cooperation and communication in a disaster (28) | 5 codes -Creating a system for cooperation and communication in a disaster | 8 codes -It is necessary to cooperate daily and to train so that information can be utilized at all times. | 15 codes -Creating a system for cooperation and communication in a disaster |

| Countermeasures for vulnerable people (14) | Appropriate response to vulnerable people (8) | 2 codes -Even though it required energy, everyone was fair and personal responses were few. | 4 codes -Nursing stations or nursing room (in emergency shelters) -Correspondence of people who are eating a lot of processed foods. | 2 codes -A system to support survivors unable to raise their voices. |

| A system for delivering special diet to people who need it (6) | – | 4 codes -People with food allergies (especially wheat) returned to their homes early because they could not eat from stockpiles. | 2 codes -Only food for general use was distributed. I wanted them to consider that there are infants, children, mildly sick people, and elderly people in emergency shelters. | |

| Cooperation among dietitians/Support for activities (14) | A system for cooperation among dietitians (8) | 3 codes -I wanted continued support for 1 week at least. | 3 codes -A system for cooperation among dietitians | 2 codes -Information tool for communication among neighbor dietitians |

| Activity contents/place as a dietitian (6) | 2 codes -It is necessary for dietitians to create a system that is positioned similarly to other occupations. | 3 codes -Support to serve as a dietitian. We cannot act arbitrarily in the government (dietitian’s work is not described in the disaster prevention plan, manual, etc.). | 1 code -I was disappointed that there was no contact from the JDA even after 1 month (other professional associations provided support information including volunteers every day). | |

| Preparation for provision of meals in emergency shelters (10) | Cooking environment in emergency shelter without lifeline (5) | 1 code -Cooking environment in emergency shelter without lifeline | 3 codes -It was necessary for dietitians to make rounds in each emergency shelter to advise about sanitation and taking turns cooking. | 1 code -Cooking environment in emergency shelter without lifeline |

| Menu suggestions for meals in emergency shelters without a gas and/or water supply (5) | 1 code -Menu suggestions for meals in emergency shelters without a gas and/or water supply | 3 codes -Menu suggestions for meals in emergency shelters without a gas and/or water supply | 1 code -Menu suggestions for meals in emergency shelters without a gas and/or water supply | |

| Rapid recovery of lifeline (9) | Rapid recovery of lifeline (9) | – | 6 codes -Lifeline recovery was slow, and it was hard to cook. | 3 codes -I think that there was not enough water, and its recovery was a little late. |

| The JDA should establish a system in advance (6) | The JDA should establish a system in advance (6) | 1 code -Even as the JDA, we need a position to assist cooking, etc., immediately. | 3 codes -Skill to prepare for independent management day to day. Training to be quick-witted. -It would be helpful if the JDA could coordinate food provision. -Booklet that can be kept at hand. | 2 codes -The JDA should build a network that can promptly share information (e.g., add e-mail address at the time of member registration). -Even as part of the JDA, it was necessary to go around directly to the hospitals or to listen to their comments from the site. |

| Support for survivors who evacuate at home(4) | Create a support system for survivors who evacuate at home (4) | 1 code -It was difficult to extend relief supplies to survivors who evacuated to their own homes. | 1 code –Correspondence to survivors who evacuated at home | 2 codes -There was no nutrition assistance for survivors with sick who evacuated at their homes. -It was better to have support in the form of public relations about how to eat because people had mostly carbohydrate-rich meals at home. |

| Rapid assistance from the government (2) | Rapid assistance from the government (2) | 1 code -Rapid assistance from the local government | – | 1 code -Rapid assistance from the government |

| Category (Number of Codes) | Subcategory (Number of Codes) | Number of Codes and Specific Code Examples (Per Each Prefecture) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwate Prefecture | Miyagi Prefecture | Fukushima Prefecture | ||

| Information for living in a disaster area (60) | Information (30) | 8 codes -Information (I spent about 3 days without knowing anything because the newspaper did not come due to the blackout.) | 18 codes -I was worried that information on the damage situation would not come. -Almost no information obtained. I should have checked where and what information I could obtain. | 4 codes -Support to make up for lack of information |

| Details of support contents received (8) | 2 codes -Details of support contents received | 2 codes -Details of support contents received | 4 codes -It was very difficult to obtain foodstuffs from our outsourcing company. I wanted information as to where I could find special diet that was available. | |

| Information on the neighborhood (8) | 1 code -Information on the neighborhood | 2 codes -I wanted to join the support if I could get information. -I could not understand the situation of disaster. The reason is that I was unable to move around because the surrounding area was covered with water due to the tsunami. I wanted information. | 5 codes -Information on the neighborhood. Opening hours of gas stations and stores. Information on the water station (I got the upper limit per person after arriving). -Information on other areas because I was unable to think about the situation of other areas. | |

| Accurate information (7) | 2 codes -Accurate information | – | 5 codes -Accurate information | |

| Information from the government (5) | – | 1 code -Information from the government | 4 codes -I wanted a clear response that the government is unable to assist us. I could get no response from the government, even though they asked us about our troubles and needs because the facility side just said that and the government side just listened. | |

| Recovery information on lifeline (2) | – | – | 2 codes -Recovery information on lifeline | |

| Accurate information on the safety of radioactivity (8) | Information on the effects of radioactivity on food and drinks and the action to be taken (6) | – | – | 6 codes -Accurate information on the safety of radioactivity (some people asked for advice about the following: They inquired with the national counseling desk but the answers varied according to each organization). -After becoming aware of the nuclear accident, I was very anxious that it was not good to eat the stored root vegetables. I was dependent on only instant foods for a while because the store was closed. |

| Accurate information on the nuclear accident (2) | – | – | 2 codes -Accurate information on the nuclear accident | |

| Telecommunications/Contact/Means of traffic (5) | Telecommunications/Contact/Means of traffic (5) | 2 codes -Telecommunications/Contact/Means of traffic | 3 codes -Communication system with other facilities | – |

| Category (Number of Codes) | Subcategory (Number of Codes) | Number of Codes and Specific Code Examples (Per Each Prefecture) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwate Prefecture | Miyagi Prefecture | Fukushima Prefecture | ||

| Manpower (20) | Manpower (14) | 1 code -I wanted a support person for paperwork. | 7 codes -In the case of the government, it is extremely difficult to maintain management of emergency shelters concurrently. I wanted physical support for emergency shelters from an early phase. | 6 codes -Manpower carrying water with polyethylene tanks -Elderly people’s hands were very full. Many people injured their lower backs due to carrying water. |

| Human resources for mass feeding/cooking (3) | 3 codes -Human resources for mass feeding/cooking | – | – | |

| Human resources for mental support (2) | 2 codes -Human resources for mental support | – | – | |

| Human resources to distribute the relief supplies (1) | – | 1 code -Human resources to distribute the relief supplies | – | |

| Dietitian/Registered dietitian (12) | Rapid dispatch of dietitian/registered dietitian (12) | 3 codes -Dietitian staffing is needed for the relief supply center. | 4 codes -It was late to start officially dispatching dietitians. | 5 codes -Member who can participate at all times (weekdays) |

| People with disaster assistance skills (6) | People with disaster assistance skills (6) | 1 code -A place to respond to when we are in trouble. | 4 codes -People who brainstorm together regarding how to assist the survivors | 1 code -I think that it will be necessary to have competent support with coordinating support activities while identifying priority issues with the local government. |

| Recruitment of human resources as a result of the shortage due to the nuclear accident (6) | Recruitment of human resources as a result of the shortage due to the nuclear accident (6) | – | 1 code -I was not able to express that I wanted support to come because it was close to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster area. | 5 codes -Because of Fukushima prefecture, the support was mainly goods. It was not a troubling thing, but I wanted the support of personnel more. The staff was also evacuated, so there was a human resource shortage. |

| Category (Number of Codes) | Subcategory (Number of Codes) | Number of Codes and Specific Code Examples (Per Each Prefecture) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwate Prefecture | Miyagi Prefecture | Fukushima Prefecture | ||

| Nothing special (25) | Nothing special (25) | 10 codes -It never crossed my mind to demand someone in particular. -It did not cause a major inconvenience for residents of the facility (in Morioka City). -Mass feeding offered to survivors by the local government were helpful. | 7 codes -I cannot recall because time has passed. -My family managed to get everything done somehow by ourselves. | 8 codes -Because I was provided with enough support, it was a great help to me. -The foods were all right, thanks to the efforts of suppliers. -Support was not particularly necessary because no great damage occurred. |

| Others (5) | Others (5) | – | 3 codes -I was not able to be active because I was busy with housework and work and missing my family. -It helped us to prepare various things, thanks to the seminar by the Miyagi dietetic association before the earthquake. -This earthquake made me deeply understand that diet can save a life. | 2 codes -It was a priority to provide our meals because our hospital was completely destroyed. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harada, M.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N. Analysis of Necessary Support in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103475

Harada M, Ishikawa-Takata K, Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N. Analysis of Necessary Support in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster Area. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(10):3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103475

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarada, Moeka, Kazuko Ishikawa-Takata, and Nobuyo Tsuboyama-Kasaoka. 2020. "Analysis of Necessary Support in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster Area" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 10: 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103475

APA StyleHarada, M., Ishikawa-Takata, K., & Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N. (2020). Analysis of Necessary Support in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster Area. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103475