Space-Time Surveillance of Negative Emotions after Consecutive Terrorist Attacks in London

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area, Data, and Methods

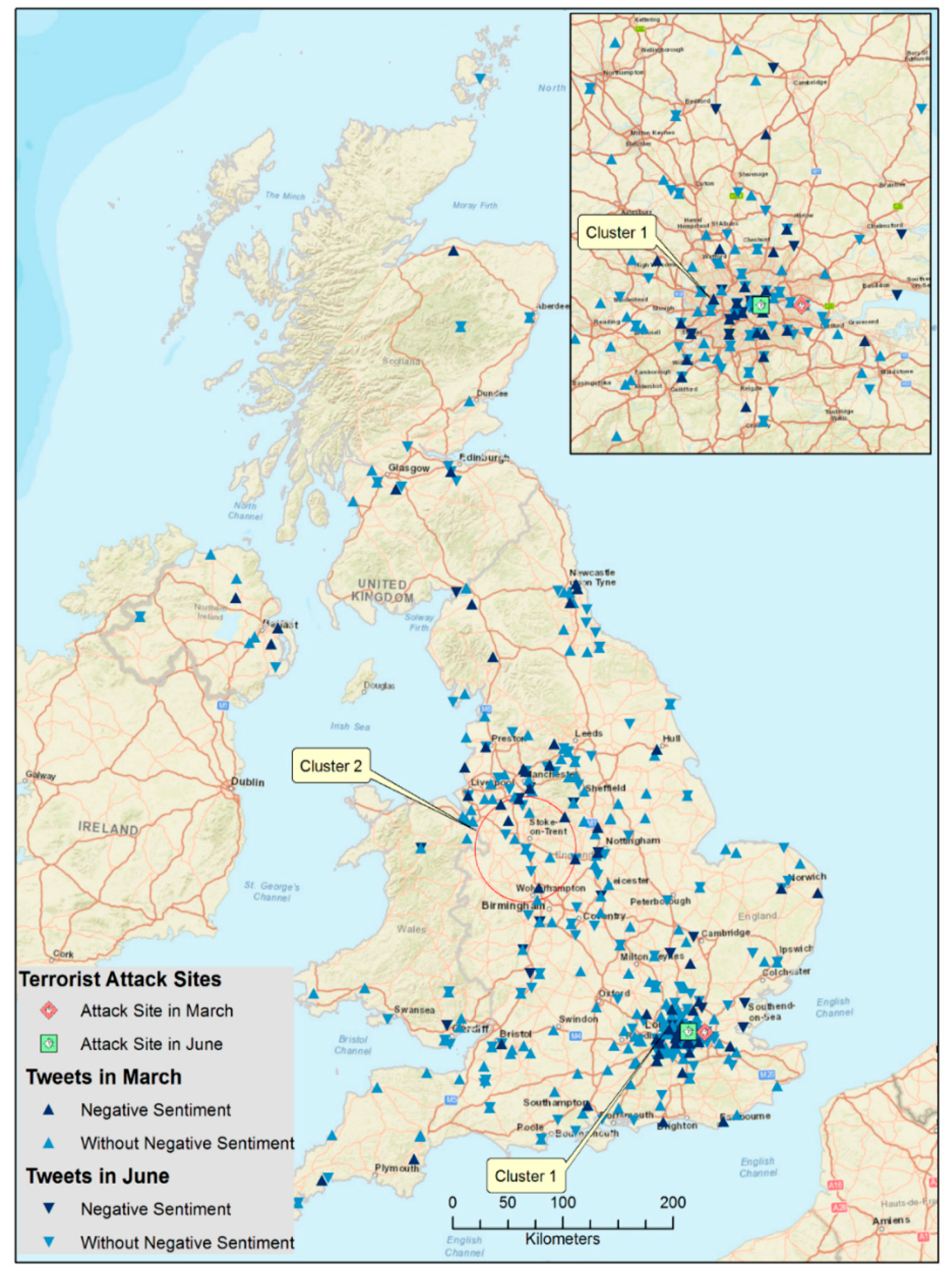

2.1. Study Area

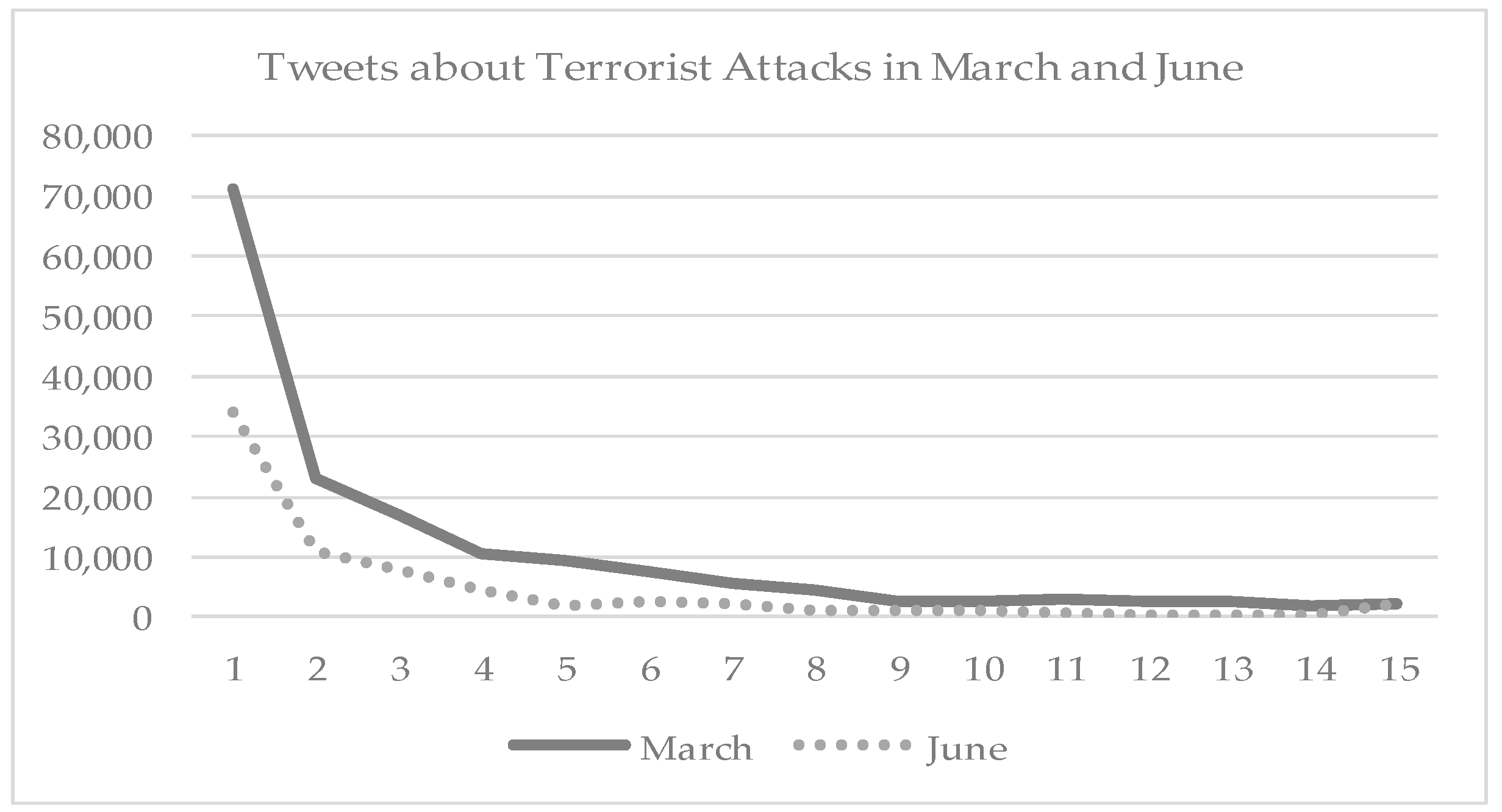

2.2. Tweet Collection

2.3. Analysis of Negative Emotions in Tweets

2.4. Cluster Detection of Negative Emotions

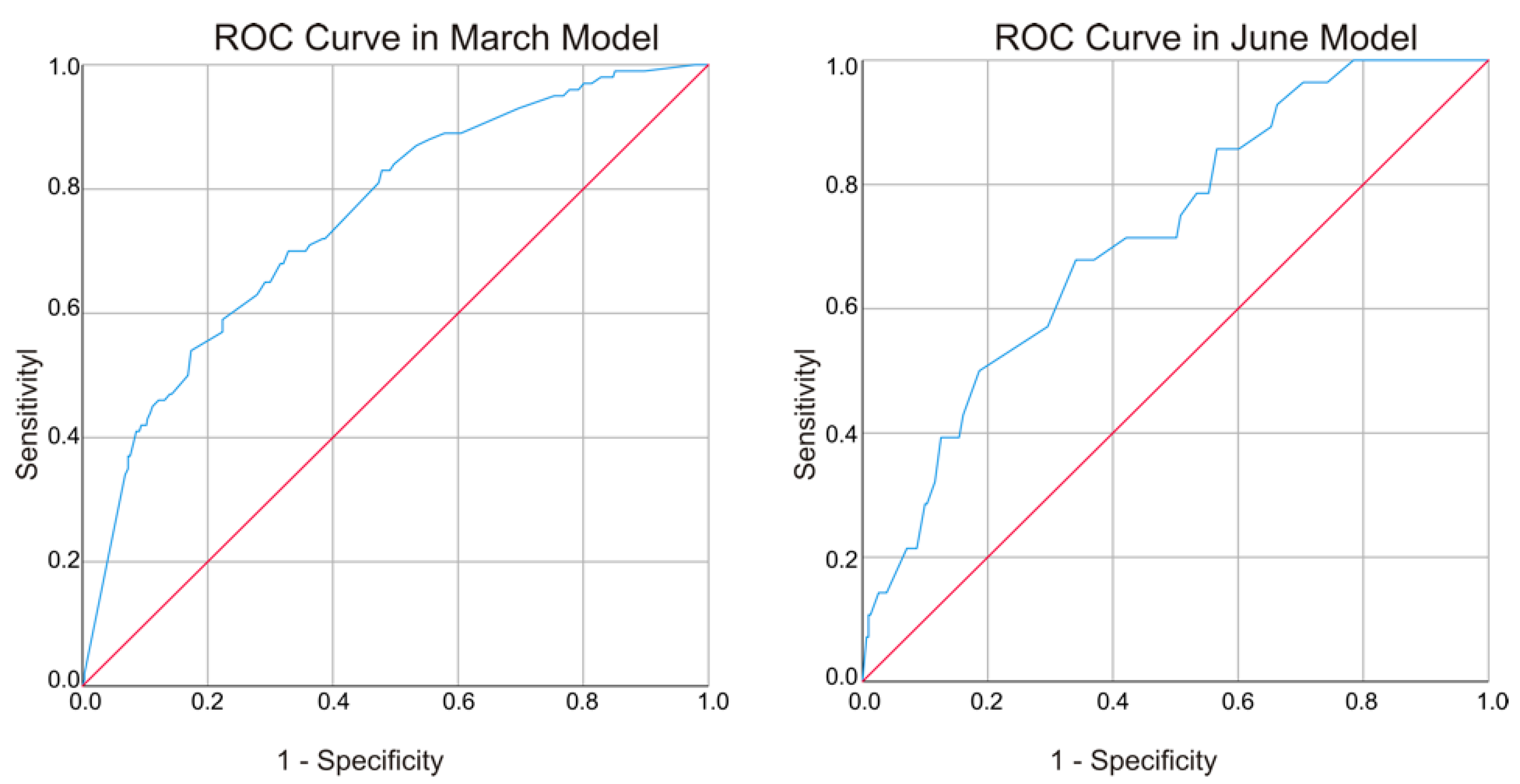

2.5. Social Characteristics Associated with Negative Tweeting

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medina, R.M.; Siebeneck, L.K.; Hepner, G.F. A Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analysis of Spatiotemporal Patterns of Terrorist Incidents in Iraq 2004–2009. Stud. Confl. Terror. 2011, 34, 862–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.S. Common statistical patterns in urban terrorism. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruebner, O.; Sykora, M.; Lowe, S.R.; Shankardass, K.; Trinquart, L.; Jackson, T.; Subramanian, S.V.; Galea, S. Mental health surveillance after the terrorist attacks in Paris. Lancet 2016, 387, 2195–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, M.T.G.; Nissen, A.; Berthelsen, M.; Heir, T. Post-traumatic stress reactions and doctor-certified sick leave after a workplace terrorist attack: Norwegian cohort study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e032693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, C.W. The terror that failed: Public opinion in the aftermath of the Bombing in Oklahoma City. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 60, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.A.; Stein, B.D.; Jaycox, L.H.; Collins, R.L.; Marshall, G.N.; Elliott, M.N.; Zhou, A.J.; Kanouse, D.E.; Morrison, J.L.; Berry, S.H. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1507–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S.; Nandi, A.; Vlahov, D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiol. Rev. 2005, 27, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, C.S.; Nixon, S.J.; Shariat, S.; Mallonee, S.; McMillen, J.C.; Spitznagel, E.L.; Smith, E.M. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999, 282, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neria, Y.; Nandi, A.; Galea, S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Ahern, J.; Resnick, H.; Kilpatrick, D.; Bucuvalas, M.; Gold, J.; Vlahov, D. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetojevic, S.; Hochmair, H.H. Analyzing the spread of tweets in response to Paris attacks. Comput. Environ. Urban. Syst. 2018, 71, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.R.; Margolin, D.; Wen, X.D. Tracking and Analyzing Individual Distress Following Terrorist Attacks Using Social Media Streams. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 1580–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, D.; Paquette, S. Emergency knowledge management and social media technologies: A case study of the 2010 Haitian earthquake. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S.; Rasmussen, L.; Patterson, D.; Shin, J.H. Hope for Haiti: An analysis of Facebook and Twitter usage during the earthquake relief efforts. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruebner, O.; Lowe, S.R.; Sykora, M.; Shankardass, K.; Subramanian, S.V.; Galea, S. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Negative Emotions in New York City After a Natural Disaster as Seen in Social Media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.J.; Mao, J.; Li, G.; Ma, C.; Cao, Y.J. Uncovering sentiment and retweet patterns of disaster-related tweets from a spatiotemporal perspective—A case study of Hurricane Harvey. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, T. Collective action and transnational terrorism. World Econ. 2003, 26, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, T. New frontiers of terrorism research: An introduction. J. Peace Res. 2011, 48, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, M. Explaining suicide terrorism: A review essay. Secur. Stud. 2007, 16, 133–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Science. Preparing for the Psychological Consequences of Terrorism: A Public Health Strategy; Committee on Responding to the Psychological Consequences of Terrorism: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. University of Maryland Global Terrorism Database. Available online: https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Goldman, O. The Globalization of Terror Attacks. Terror. Political Violence 2011, 23, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, J.L.; Khashan, A.S.; Baker, P.N. Reduced infant birth weight in the North West of England consequent upon ‘maternal exposure’ to 7/7 terrorist attacks on central London. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 31, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecklov, G.; Goldstein, J.R. Terror attacks influence driving behavior in Israel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14551–14556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; Byrne, C.M.; Diaz, E.; Kaniasty, K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part, I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2002, 65, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, A. Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic distress. Health Psychol. 1990, 9, 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.L.; Lindy, J.D.; Grace, M.C.; Gleser, G.C.; Leonard, A.C.; Korol, M.; Winget, C. Buffalo Creek survivors in the second decade: Stability of stress symptoms. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1990, 60, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Green, B.L. Mental health effects of natural and human-made disasters. PTSD Res. Q. 1992, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Coppersmith, G.; Dredze, M.; Harman, C. Quantifying Mental Health Signals in Twitter. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality, Baltimore, MD, USA, 22–27 June 2014; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Twitter, Inc. Rate Limiting. Available online: https://developer.twitter.com/en/docs/basics/rate-limiting (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Sykora, M.; Jackson, T.; O’Brien, A. Emotive ontology: Extracting fine-grained emotions from terse, informal messages. IADIS Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2013, 2013, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.J.; Kumar, R. Sentiment Analysis from Social Media in Crisis Situations. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computing, Communication & Automation (ICCCA), Noida, India, 15–16 May 2015; pp. 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.H.; Qamar, U.; Bashir, S. eSAP: A decision support framework for enhanced sentiment analysis and polarity classification. Inf. Sci. 2016, 367, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.H.; Qamar, U.; Bashir, S. Senti-CS: Building a lexical resource for sentiment analysis using subjective feature selection and normalized Chi-Square-based feature weight generation. Expert Syst. 2016, 33, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.R.; Cao, D.L.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Chen, F.H. Survey of visual sentiment prediction for social media analysis. Front. Comput. Sci. 2016, 10, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltoglou, G. Sentiment-Based Event Detection in Twitter. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 1576–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumaker, R.P.; Jarmoszko, A.T.; Labedz, C.S. Predicting wins and spread in the Premier League using a sentiment analysis of twitter. Decis. Support. Syst. 2016, 88, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulldorff, M.; Heffernan, R.; Hartman, J.; Assuncao, R.M.; Mostashari, F. A space-time permutation scan statistic for the early detection of disease outbreaks. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochmair, H.; Cvetojevic, S. Assessing the Usability of Georeferenced Tweets for the Extraction of Travel Patterns: A Case Study for Austria and Florida; Austrian Acad Science Press: Vienna, Austria, 2014; pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kulldorff, M. An isotonic spatial scan statistic for geographical disease surveillance. J. Natl. Inst. Public Health 1999, 48, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- University of Essex, University of Manchester and Jisc. Deprivation Data. Available online: https://census.ukdataservice.ac.uk/get-data/related/deprivation.aspx (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- U.K. National Health Service. NHS: Business Definitions. Available online: https://www.datadictionary.nhs.uk/data_dictionary/nhs_business_definitions/l/lower_layer_super_output_area_de.asp?shownav=1 (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- U.S. Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau Glossary on Census Divisions and Census Regions. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/about/glossary.html (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Budenz, A.; Klassen, A.; Purtle, J.; Tov, E.Y.; Yudell, M.; Massey, P. Mental illness and bipolar disorder on Twitter: Implications for stigma and social support. J. Ment. Health. 2019, 29, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, H.; Kwon, K.H.; Rao, H.R. A system for intergroup prejudice detection: The case of microblogging under terrorist attacks. Decis. Support. Syst. 2018, 113, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, F.E.J.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B. Multivariable prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat. Med. 1996, 15, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Harrell, F.E.J.; Habbema, J.D.F. Prognostic modelling with logistic regression analysis: A comparison of selection and estimation methods in small data sets. Stat. Med. 2000, 19, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittinghoff, E.; McCulloch, C.E. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and cox regression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Lemeshow, S.A.; Sturdviant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness & correlation. J. Mach. Learn. Technol. 2011, 2, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mahat-Shamir, M.; Hoffman, Y.; Pitcho-Prelorentzos, S.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Lavenda, O.; Ring, L.; Halevi, U.; Ellenberg, E.; Ostfeld, I.; Ben-Ezra, M. Truck attack: Fear of ISIS and reminder of truck attacks in Europe as associated with psychological distress and PTSD symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 267, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrzesniewski, A. “It’s not just a job”: Shifting meanings of work in the wake of 9/11. J. Manag. Inq. 2002, 11, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inness, M.; Barling, J. Terrorism. In Handbook of Work Stress; Barling, J., Kelloway, E.K., Frone, M.R., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 377–397. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlingson, K. Darren Osborne Jailed for Life for Finsbury Park Terrorist Attack. The Guardian. 2 February 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/feb/02/finsbury-park-attack-darren-osborne-jailed (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Mortimer, C. Darren Osborne: Family of Man Arrested after Finsbury Park Mosque Terror Attack Says He Is ‘Troubled’ but ‘not Racist’. Independent. 19 June 2017. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/finsbury-park-mosque-terror-attack-muslims-darren-osborne-van-driver-family-neighbour-troubled-a7798256.html (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Goldmann, E.; Galea, S. Mental Health Consequences of Disasters. Ann. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, R.A. Acute stress disorder as a predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.; Mills, J.W.; Leitner, M. Katrina and vulnerability: The geography of stress. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2007, 18, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, M. Terrorism Research: The Record. Int. Interact. 2014, 40, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, T. Terrorism and counterterrorism: An overview. Oxf. Econ. Pap. New Ser. 2015, 67, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara, A. Grief intensity, coping and psychological health among family members and friends following a terrorist attack. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M. The Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder with Tendency to Forgive, Social Support, and Psychosocial Functioning of Terror Survivors. Health Soc. Work 2018, 43, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, G.; Lutz, C. Representativeness of Social Media in Great Britain: Investigating Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Pinterest, Google plus, and Instagram. Am. Behav. Sci. 2017, 61, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, Q.Y.; Wu, K. Understanding social media data for disaster management. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 1663–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, M.H. Research challenges and opportunities in mapping social media and Big Data. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 42, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Y.; Tsou, M.H.; Clarke, K.C. Do global cities enable global views? Using Twitter to quantify the level of geographical awareness of U.S. Cities. PLoS ONE 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, L.; Morgan, J. Who Tweets with Their Location? Understanding the Relationship between Demographic Characteristics and the Use of Geoservices and Geotagging on Twitter. PLoS ONE 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalley, M.G.; Brewin, C.R. Mental health following terrorist attacks. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Longitude/Latitude | Date | Time | Tweet | Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−0.775435, 51.279904) | 3/23/2017 | 20:58:23 | So sad watching the vigil in London today. Our thoughts and amp; prayers are with everyone who was affected by yesterday’s attack | 1 |

| (−3.0812071, 51.549936) | 3/27/2017 | 17:32:17 | I think they are sensible and amp; very necessary to stop a tory government exploiting Brexit to attack people’s rights… | 1 |

| (−0.297251, 51,685439) | 3/29/2017 | 6:56:29 | the last legs’ response to the London attack is f—brilliant ???? | 1 |

| (−0.15191, 51.410792) | 6/6/2017 | 22:05:35 | r.i.p ???? I had tears in my eyes walking past where the attack was London you are beautiful ?? London strong | 1 |

| (−0.422572, 53.719616) | 3/23/2017 | 21:32:50 | Thank you to all my twitter friends for your support after the attack on London | 0 |

| (−0.213503, 51.512805) | 3/30/2017 | 17:44:10 | London attack: Khalid Masood ‘died from shot to chest’ | 0 |

| (−0.187894, 51.483718) | 6/6/2017 | 9:10:17 | A minute’s silence will be held at 11 am today in remembrance of those who died in the London Bridge attack?? | 0 |

| Title | Geotagged Tweets (Number) | Negative Tweets (Number) | Percent of Negative Tweets |

|---|---|---|---|

| March | 717 | 100 | 13.95% |

| June | 339 | 28 | 8.26% |

| Social Characteristics | March | June | Decrease a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Tweets | % Tweets | # Tweets | % Tweets | ||

| Income | |||||

| Most deprived | 117 | 16.3 | 48 | 14.2 | 59.0% |

| Moderate deprivation | 158 | 22.0 | 71 | 20.9 | 55.1% |

| Moderate affluence | 240 | 33.5 | 110 | 32.5 | 54.2% |

| Most affluence | 202 | 28.2 | 110 | 32.4 | 45.5% |

| Employment | |||||

| Most deprived | 107 | 14.9 | 41 | 12.1 | 61.7% |

| Moderate deprivation | 112 | 15.6 | 60 | 17.7 | 46.4% |

| Moderate affluence | 269 | 37.5 | 108 | 31.9 | 59.9% |

| Most affluence | 229 | 32.0 | 130 | 38.3 | 43.2% |

| Education | |||||

| Most deprived | 43 | 6.0 | 31 | 9.2 | 27.9% |

| Moderate deprivation | 153 | 21.3 | 58 | 17.1 | 62.1% |

| Moderate affluence | 277 | 38.6 | 133 | 39.2 | 52.0% |

| Most affluence | 244 | 34.1 | 117 | 34.5 | 52.0% |

| Crime | |||||

| Most deprived | 161 | 22.4 | 90 | 26.5 | 44.1% |

| Moderate deprivation | 251 | 35.0 | 100 | 29.5 | 60.2% |

| Moderate affluence | 159 | 22.2 | 79 | 23.3 | 50.3% |

| Most affluence | 146 | 20.4 | 70 | 20.7 | 52.1% |

| Social Characteristics | March Incident | June Incident | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Rate a | Odds Ratio (95% CI b) | Negative Rate a | Odds Ratio (95% CI b) | |

| Income | ||||

| Most deprived | 36 | 2.4 (0.39, 14.99) | 6 | 12.23 (0.43, 345.15) |

| Moderate deprivation | 6 | 0.32 (0.08, 1.26) | 6 | 1.3 (0.15, 11.28) |

| Moderate affluence | 10 | 0.48 (0.18, 1.25) | 10 | 1.12 (0.29, 4.29) |

| Most affluence c | 12 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| Employment | ||||

| Most deprived | 36 | 1.5 (0.22, 10.19) | 5 | 0.03 (0.001, 1.49) |

| Moderate deprivation | 13 | 2.05 (0.56, 7.53) | 7 | 0.32 (0.04, 2.64) |

| Moderate affluence | 9 | 1.95 (0.76, 4.98) | 9 | 1.52 (0.43, 5.41) |

| Most affluence c | 10 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| Education | ||||

| Most deprived | 9 | 0.49 (0.12, 2.06) | 10 | 8.23 (0.74, 92.11) |

| Moderate deprivation | 31 | 2.87 * (1.15, 7.16) | 7 | 1.59 (0.34, 7.48) |

| Moderate affluence | 10 | 1.1 (0.54, 2.24) | 9 | 1.37 (0.48, 3.89) |

| Most affluence c | 9 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| Crime | ||||

| Most deprived | 6 | 0.43 (0.15, 1.19) | 3 | 0.12 * (0.02, 0.71) |

| Moderate deprivation | 19 | 0.69 (0.31, 1.5) | 5 | 0.23 * (0.06, 0.9) |

| Moderate affluence | 16 | 1.44 (0.71, 2.89) | 14 | 0.87 (0.31, 2.47) |

| Most affluence c | 12 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, D.; Wang, R. Space-Time Surveillance of Negative Emotions after Consecutive Terrorist Attacks in London. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114000

Dai D, Wang R. Space-Time Surveillance of Negative Emotions after Consecutive Terrorist Attacks in London. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114000

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Dajun, and Ruixue Wang. 2020. "Space-Time Surveillance of Negative Emotions after Consecutive Terrorist Attacks in London" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 11: 4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114000

APA StyleDai, D., & Wang, R. (2020). Space-Time Surveillance of Negative Emotions after Consecutive Terrorist Attacks in London. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114000