Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning: A Concise Overview of Current Laws and Policies Addressing Access to Rehabilitation in Five European Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1

- How do national laws govern the provision of rehabilitation?

- 2

- What aspects of rehabilitation services are subject to State regulation?

- 3

- How is rehabilitation being addressed in national health policies and strategies?

- 4

- What are the common (or divergent) approaches to rehabilitation policy development?

2. Methods

2.1. Country Selection

2.2. Design

2.2.1. Data Sources

2.2.2. Terminology and Search Terms

2.2.3. Document Identification

2.2.4. Document Selection and Analysis

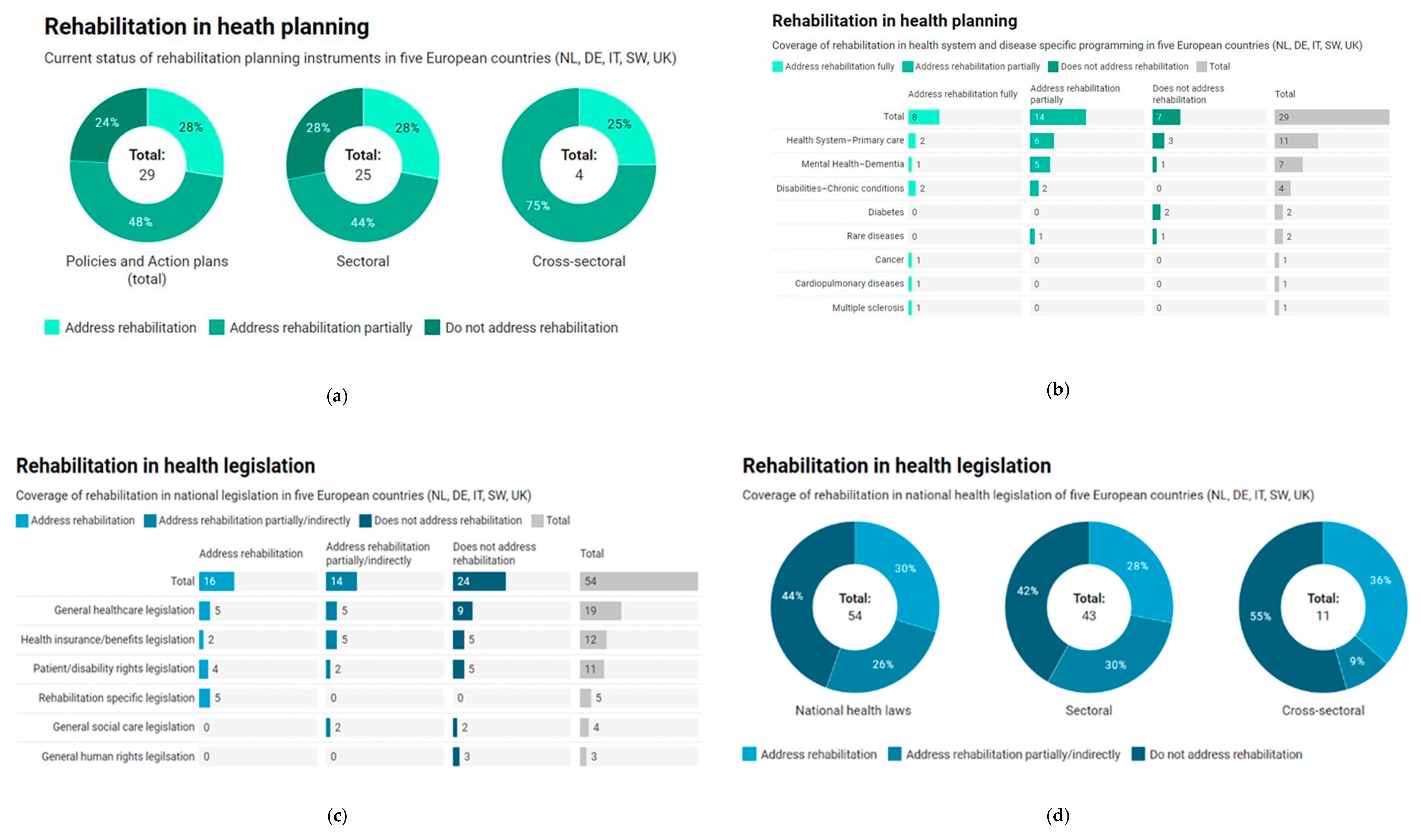

3. Results

3.1. United Kingdom

3.2. Netherlands

3.3. Sweden

3.4. Germany

3.5. Italy

4. Discussion

4.1. Positioning of Rehabilitation in National Legislation and Policies

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | National Laws | Rehabilitation in National Legislation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document Title/Timeframe | Sectoral Laws Developed by Governments | Cross Sectoral Laws | |||||

| UK | Offender Rehabilitation Act [2014] [70] | Direct | |||||

| Care Act [2014] [29] | Indirect | ||||||

| Health Act [2009] [30] | None | ||||||

| Health and Social Care Act [2012] [31] | None | ||||||

| The Local Health Boards (Functions) (Wales) Regulations [2003] [71] | Indirect | ||||||

| Health Act 1999 (Commencement No. 17) Order 2017 [2017] [72] | None | ||||||

| The Health Act 1999 (Consequential Amendments) (Nursing and Midwifery) Order 2004 [2004] [73] | Indirect | ||||||

| Independent Health Care Regulations (Northern Ireland) [2005] [74] | None | ||||||

| Equality Act [2010] [75] | None | ||||||

| Community Care (Delayed Discharge etc.) Act [2003] [76] | Indirect | ||||||

| The National Health Service Superannuation Scheme (Scotland) Regulations [2011] [77] | Indirect | ||||||

| National Health Service Act [2006] [32] | Indirect | ||||||

| IT | Ministerial Decree No. 182 of 29 March 2001: Regulation concerning the identification of the figure of the psychiatric rehabilitation technician [Legge n. 182: Regolamento concernente la individuazione della figura del tecnico della riabilitazione psichiatrica [2001] [78] | Direct | |||||

| Law No. 284: Provisions for the prevention of blindness and for the visual rehabilitation and social and occupational integration of the blind multiminor [Legge n. 284: “Disposizioni per la prevenzione della cecità e per la riabilitazione visiva e l’integrazione sociale e lavorativa dei ciechi pluriminorati.”] [1997] [79] | Direct | ||||||

| Rehabilitation National Plan: An Italian Act [2011] [58] | Direct | ||||||

| Law No. 328: “Framework law for the implementation of the integrated system of interventions and social services” [“Legge quadro per la realizzazione del sistema integrato di interventi e servizi sociali”] [2000] [57] | Indirect | ||||||

| Law No. 104: “Framework law for the care, social integration and rights of disabled people.” [Legge-quadro per l’assistenza, l’integrazione sociale e i diritti delle persone handicappate] [1992] [56] | Direct | ||||||

| Law No. 279: Regulation for the establishment of the national network of rare diseases and exemption from participation in the cost of the related health services pursuant to Article 5(1) (b) of Legislative Decree No 124 of 29 April 1998 [“Regolamento di istituzione della rete nazionale delle malattie rare e di esenzione dalla partecipazione al costo delle relative prestazioni sanitarie ai sensi dell’articolo 5, comma 1, lettera (b) del decreto legislativo 29 aprile 1998, n. 124.”] [2001] [80] | Indirect | ||||||

| Law No. 332: Regulation containing rules for the provision of prosthetic assistance within the National Health Service: method of provision and rates [“Regolamento recante norme per le prestazioni di assistenza protesica erogabili nell’ambito del Servizio sanitario nazionale: modalità di erogazione e tariffe.”] [1999] [81] | Indirect | ||||||

| Law No. 18 of 3 March 2009 “Ratification and implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with Optional Protocol, done in New York on 13 December 2006 and establishment of the National Observatory on the Condition of Persons with Disabilities” [“Ratifica ed esecuzione della Convenzione delle Nazioni Unite sui diritti delle persone con disabilità, con Protocollo opzionale, fatta a New York il 13 dicembre 2006 e istituzione dell’Osservatorio nazionale sulla condizione delle persone con disabilità”] [2009] [82] | Direct | ||||||

| SW | Health and Medical Services Act [Hälso-och sjukvårdslag (1982:763)] [1982] [46] | Direct | |||||

| Law Amending the Health and Medical Services Act [ SFS 2014:822 Lag om ändring i hälso- och sjukvårdslagen (1982:763)] [2014] [47] | Direct | ||||||

| Law on Financial Coordination of Rehabilitation Efforts (1210) [ Lag (2003:1210) om finansiell samordning av rehabiliteringsinsatser] [2003] [45] | Direct | ||||||

| Law Amending the Health and Medical Services Act [ SFS 2003:194 Lag om ändring i hälso-och sjukvårdslagen (1982:763)] [2003] [83] | None | ||||||

| Law Amending the Health and Medical Services Act [ SFS 2018:143 Lag om ändring i hälso- och sjukvårdslagen (2017:30)] [2018] [84] | None | ||||||

| Act (1993:387) concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments [1993] [85] | None | ||||||

| Assistance Benefit Act (No. 389) [Lag (1993:389) om assistansersättning] [1993] [86] | None | ||||||

| Regulation No. 526 on State Authorities Responsibility for Implementing Disability Policy [Förordning (2001:526) om de statliga myndigheternas ansvar för genomförande av funktionshinderspolitiken] [2001] [87] | None | ||||||

| Discrimination Act (2008:567)[Diskrimineringslag (2008:567)] [2008] [88] | None | ||||||

| NL | Patients’ Rights (Care Sector) Act[Wet Cliëntenrecht zorg] [2011] [89] | None | |||||

| Youth Act [Jeugdwet] [2014] [90] | None | ||||||

| Public Health Act [Wet publieke gezondheid] [2008] [91] | None | ||||||

| Healthcare Insurance Act (Zorgverzekeringswet) [2005] [92] | None | ||||||

| Long-Term Care Act (Wet langdurige zorg) [2014] [93] | None | ||||||

| Social Support Act (Wet maatschappelijke ondersteuning) [2015] [94] | None | ||||||

| Individual Health Care Professions Act (Wet op de beroepen in de individuele gezondheidszorg) [1993] [95] | None | ||||||

| Chronically Ill and Disabled Persons (Allowances) Act [Wet tegemoetkoming chronisch zieken en gehandicapten (WTCG)] [2008] [96] | Indirect | ||||||

| Health Care Allowance Act (Wet op de zorgtoeslag) [2005] [97] | None | ||||||

| Access to Health Insurance Act 1998 [Wet op de toegang tot ziektekostenverzekeringen 1998] [1998] [37] | Direct | ||||||

| Health Care Market Regulation Act [Wet Marktordening Gezondheidszorg] [2006] [98] | None | ||||||

| Health Care Tariffs Act [Wet tarieven gezondheidszorg] [1980] [99] | None | ||||||

| DE | Federal Act on Participation [ Gesetz zur Stärkung der Teilhabe und Selbstbestimmung von Menschen mit Behinderungen (Bundesteilhabegesetz—BTHG) [2016] [60] | Direct | |||||

| Second Bill to Strengthen Long-Term Care [2015] [100] | Direct | ||||||

| Social Code Book IX: Rehabilitation and Participation of Disabled Persons [Sozialgesetzbuch - Neuntes Buch—(SGB IX) Rehabilitation und Teilhabe behinderter Menschen] [2001] [50] | Direct | ||||||

| Health Care Structure Act (Gesundheitsstrukturgesetz, GSG) [1992] [101] | None | ||||||

| SHI Reform Act (Zweites GKV-Neuordnungsgesetz) [1997] [102] | Indirect | ||||||

| Health Care Reform Act (GKV-Gesundheitsreformgesetz) [2000] [103] | Direct | ||||||

| Risk Structure Compensation Reform Act (Gesetz zur Reform des Risikostrukturausgleich) [2001] [104] | Indirect | ||||||

| Act to strengthen competition within SHI (GKV-Wettbewerbsstärkungsgesetz, GKV-WSG) [2007] [105] | Direct | ||||||

| Law on the structural further development of nursing care insurance (Pflege-Weiterentwicklungsgesetz) [2008] [106] | Indirect | ||||||

| Act on the Further Development of Organizational Structures in Statutory Health Insurance (GKV-OrgWG) [2008] [107] | Indirect | ||||||

| Disability Equality Act [ Gesetz zur Gleichstellung von Menschen mit Behinderungen (Behindertengleichstellungsgesetz—BGG)] [2002] [108] | None | ||||||

| General Equal Treatment Act [ Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz(AGG)] [2006] [109] | None | ||||||

| Social Code Book V [Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch (V)—Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung—(Artikel 1 des Gesetzes v. 20. Dezember 1988, BGBl. I S. 2477)] [1988] [110] | Direct | ||||||

| Total | 12 | 13 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

Directly addresses rehabilitation health services; includes improvement of (access to) rehabilitation care as one of its objectives.

Directly addresses rehabilitation health services; includes improvement of (access to) rehabilitation care as one of its objectives.  Indirectly addresses rehabilitation health services; does not have rehabilitation care as one of its aims but explicitly refers to it.

Indirectly addresses rehabilitation health services; does not have rehabilitation care as one of its aims but explicitly refers to it.  Does not include rehabilitation.

Does not include rehabilitation.  Directly addresses comprehensive, cross-sectoral rehabilitation.

Directly addresses comprehensive, cross-sectoral rehabilitation.  Addresses disability human rights and explicitly refers to rehabilitation.

Addresses disability human rights and explicitly refers to rehabilitation.  Does not include rehabilitation.

Does not include rehabilitation.| Country | National Policies | Rehabilitation in National Planning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document Title/Timeframe | Sectoral Policies Developed by MoH a | Cross Sectoral Policies | |||||

| UK | Strategic plan for the next four years: Better outcomes by 2020 [2016–2020] [111] | None | |||||

| NHS Outcomes Framework: at-a-glance [2016,2017] [112] | Indirect | ||||||

| The NHS five year forward view[2014–2019] [113] | Indirect | ||||||

| Achieving world-class cancer outcomes: A Strategy for England [2015–2020] [34] | Direct | ||||||

| Tackling the Diabetes Crisis Together: Our Ambition to 2019 [2015–2019] [114] | None | ||||||

| Five Year Forward View for Mental Health [2016–2021] [115] | Indirect | ||||||

| Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020: Implementation Plan [2016–2020] [116] | Indirect | ||||||

| Roadmap 2025: achieving disability equality by 2025 [2009–2025] [117] | Indirect | ||||||

| NHS England’s business plan 2014/15–2016/17: Putting Patients First [2014/15–2016/17] [118] | Indirect | ||||||

| Using Allied Health Professionals to transform health, care and wellbeing [2016/17–2020/21] [119] | Indirect | ||||||

| UK Strategy for Rare Diseases [2014–2020] [120] | None | ||||||

| DE | National Plan of Action for People with Rare Diseases: Action Fields, Recommendations, and Proposed Actions [2013–] [121] | Indirect | |||||

| Action Plan on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities [2013–2017] [53,122] | Indirect | ||||||

| National Action Plan 2.0 of the Government [Nationaler Aktionsplan 2.0 der Bundesregierung zur UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention (UN-BRK)] [2016–2021] [51] | Direct | ||||||

| IT | Rehabilitation National Plan: An Italian Act[2011–] [58] | Direct | |||||

| Rehabilitation Guidance Plan [Piano d’indirizzo per la Riabilitazione] [2011–] [123] | Direct | ||||||

| National Action Plan for Mental Health [Piano di azioni nazionale per la salute mentale (PANSM)] [2013–] [124] | Indirect | ||||||

| National Plan of Chronicity [Piano Nazionale della Cronicità] [2016] [125] | Direct | ||||||

| The Italian Dementia National Plan [Piano nazionale demenze] [2014–] [126,127] | Direct | ||||||

| NL | Health Close to People (National Policy Document) [2012–2016] [42] | Indirect | |||||

| Outcome Based Health Care [2018–2022] [128] | None | ||||||

| Strategic policy plan CVON 2015–2020 [Strategisch beleidsplan CVON 2015–2020] [2015–2020] [129] | None | ||||||

| Program Longer At Home Working Together - Plan of Action 2018–2021 [Programma Langer Thuis - Samen aan de slag - Plan van Aanpak 2018–2021] [2018–2021] [40] | Indirect | ||||||

| National Action Program for Chronic Pulmonary Diseases: Better and more effective lung care [Nationaal Actieprogramma Chronische Longziekten: Betere en doelmatigere longzorg] [2014–2019] [41] | Direct | ||||||

| Delta Plan for Dementia [Deltaplan Dementie] [2012–2020] [130,131] | None | ||||||

| Diabetes until 2025: Prevention and Care in Coherence [Diabetes tot 2025: preventie en zorg in samenhang] [2009–2025] [132] | None | ||||||

| SW | The Government’s strategy in the area of psychic health: Five Focus Areas Five Years Ahead [REGERINGENS STRATEGI INOM OMRÅDET PSYKISK HÄLSA 2016–2020:Fem fokusområden fem år framåt] [2016–2020] [48] | Indirect | |||||

| Dementia strategy focusing on care [2018–] [133] | Indirect | ||||||

| National Guidelines for Multiple Sclerosis Care [Nationella riktlinjer för vård vid multipel skleros (MS)] [2016] [134] | Direct | ||||||

| Total | 7 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 3 | ||

Directly addresses rehabilitation health services: includes improvement of (access to) rehabilitation care as one of its objectives.

Directly addresses rehabilitation health services: includes improvement of (access to) rehabilitation care as one of its objectives.  Indirectly addresses rehabilitation health services: does not have rehabilitation care as one of its aims but explicitly refers to.

Indirectly addresses rehabilitation health services: does not have rehabilitation care as one of its aims but explicitly refers to.  Does not include rehabilitation.

Does not include rehabilitation.  Directly addresses comprehensive, cross sectoral rehabilitation.

Directly addresses comprehensive, cross sectoral rehabilitation.  Addresses disability human rights and explicitly refers to rehabilitation.

Addresses disability human rights and explicitly refers to rehabilitation.  Does not include rehabilitation.

Does not include rehabilitation.References

- World Health Organization; World Bank. World Report on Disability; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The need to scale up rehabilitation. In Rehabilitation 2030: A Call for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation: Key for Health in the 21st Strategy; WHO Doc: WHO/NMH/NVI/17.3; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, S.G.; Siegert, R.J.; Taylor, W.J. Interprofessional Rehabilitation: A Person-Centred App.roach; Dean, S.G., Siegert, R.J., Taylor, W.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, A.B.; Cantista, P.; Ceravolo, M.G.; Christodoulou, N.; Delarque, A.; Gutenbrunner, C.; Rehabilitation Medicine (EARM); European Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ESPRM); European Union of Medical Specialists PRM section (UEMS-PRM section); European College of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (ECPRM); et al. White Book on Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine in Europe, Chapter 2. Why rehabilitation is needed by individual and society. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 54, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly, 24 January 2007, A/RES/61/106. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/45f973632.html (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Skempes, D.; Stucki, G.; Bickenbach, J. Health-Related rehabilitation and human rights: Analyzing states’ obligations under the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, R.; Blümel, M. Tackling Chronic Disease in Europe: Strategies, Interventions and Challenges; WHO Regional Office Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, E.; McKee, M. Caring for People with Chronic Conditions: A Health System Perspective; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, E.; Knai, C.; McKee, M. Managing Chronic Conditions: Experience in Eight Countries; World Health Organization, on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, L. Access to Healthcare by People with Disabilities in Europe—A Comparative Study of Legal Frameworks and Instruments (Part 3, Rehabili.); Academic Network of European Disability Experts: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; pp. 124–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenov, K.; Mills, J.-A.; Chatterji, S.; Cieza, A. Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation 2030: A call for Action—Meeting Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation 2030: A Call for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Health 2020: A European Policy Framework and Strategy for the 21st Century; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for Implementation of the European Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2012−2016; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in Health Systems; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Skempes, D. Health Related Rehabilitation and Human Rights: Turning Fine Aspirations into Measurable Progress. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Laws. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-laws/legal-systems/health-laws/en/ (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- World Health Organization. Health Law. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-laws-and-universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Clarke, D. Chapter 10, law, regulation and strategizing for health. In Strategizing National Health Health in the 21st Century: A Handbook; Schmets, G., Rajan, D., Kadandale, S., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Policy. Available online: https://www.who.int/topics/health_policy/en/ (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- World Health Organization. Health Systems Strengthening Glossary. Available online: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/hss_glossary/en/ (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soja, A.M.; Zwisler, A.D.; Frederiksen, M.; Melchior, T.; Hommel, E.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Madsen, M. Use of intensified comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation to improve risk factor control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance—the randomized DANish StUdy of impaired glucose metabolism in the settings of cardiac rehabilitation (DANSUK) study. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humanity & Inclusion UK. Rehabilitation and Diabetes–Factsheet. Humanity & Inclusion: Lyon, France, 2017; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cylus, J.; Richardson, E.; Findley, L.; Longley, M.; O’Neill, C.; Steel, D. United Kingdom: Health System Review; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015; Volume 17, p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. Care Act 2014 (c. 23), United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. Health Act 2009 (c. 21), United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. Health and Social Care Act 2012 (c. 7), United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. National Health Service Act 2006 (c. 41), United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England. Commissioning Guidance for Rehabilitation; NHS England: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Cancer Taskforce. Achieving World-Class Cancer Outcomes: A Strategy for England 2015–2020; Independent Cancer Taskforce: London, UK, 2015; pp. 4–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman, M.; Boerma, W.; van den Berg, M.; Groenewegen, P.; de Jong, J.; van Ginneken, E. The Netherlands: Health System Review; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Volume 18, p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneman, M.; de Jong, J.D. The basic benefit package: Composition and exceptions to the rules. A case study. Health Policy 2015, 119, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- The Government and the States General. Access to Health Insurance Act 1998 [Wet op de toegang tot ziektekostenverzekeringen 1998]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Healthcare in the Netherlands; Ministry of Health: Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sport: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; p. 32.

- SVB. What is the Long-Term Care Act (Wlz). Available online: https://www.svb.nl/en/the-wlz-scheme/what-is-the-long-term-care-act-Wlz (accessed on 29 April 2019).

- Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport. Program Longer At Home Working together–Plan of Action 2018–2021 [Programma Langer Thuis–Samen aan de slag–Plan van Aanpak 2018–2021]; Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; p. 44.

- Long Alliance Netherlands [Long Alliantie Nederland] (LAN). National Action Program for Chronic Pulmonary Diseases: Better and More Effective Lung Care [Nationaal Actieprogramma Chronische Longziekten: Betere en doelmatigere longzorg]; National Action Programme Chronic Pulmonary Diseases: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2014; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport. Health Close to People: National Policy Document on Health; Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS): The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012; p. 86.

- Anell, A.; Glenngård, A.; Merkur, S. Sweden: Health System Review; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012; Volume 14, p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Glenngård, A.H. The Swedish Health Care System. Available online: https://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/sweden/ (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Government of Sweden. Law on Financial Coordination of Rehabilitation Efforts (1210) [Lag (2003:1210) om finansiell samordning av rehabiliteringsinsatser]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2003.

- Government of Sweden. Health and Medical Services Act [Hälso-och sjukvårdslag (1982:763)]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 1982.

- Government of Sweden. Law Amending the Health and Medical Services Act [SFS 2014:822 Lag om ändring i hälso- och sjukvårdslagen (1982:763)]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2014.

- National Coordinators in the Field of Mental Health [Nationell samordnareinom området psykisk hälsa]. The Government’s Strategy in the Area of Psychic Health: Five Focus Areas Five Years Ahead [regeringens strategi inom området psykisk hälsa 2016–2020: Fem fokusområden fem år framåt]; Ministry of Health: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; p. 33.

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Health Care in Germany; Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG): Köln, Germany, 2015; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Social Code Book IX: Rehabilitation and Participation of Disabled Persons [Sozialgesetzbuch–Neuntes Buch–(SGB IX) Rehabilitation und Teilhabe behinderter Menschen]; Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. National Action Plan 2.0 of the Government [Nationaler Aktionsplan 2.0 der Bundesregierung zur UN-Behindertenrechtskonvention (UN-BRK)]; Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 4–359.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021: Better Health for All People with Disability; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Action Plan on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities; BMZ: Bonn, Germany, 2013; pp. 4–19.

- Paris, V.; Devaux, M.; Wei, L. Health Systems Institutional Characteristics. In OECD Health Working Papers No. 50; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, F.; de Belvis, A.; Valerio, L.; Longhi, S.; Lazzari, A.; Fattore, G.; Ricciardi, W.; Maresso, A. Italy: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit 2014, 16, 168. [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Republic. Law No. 104: “Framework Law for the Care, Social Integration and Rights of Disabled People.” [Legge-Quadro per L’assistenza, L’integrazione Sociale e i Diritti Delle Persone Handicapp.ate]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Republic. Law No. 328: “Framework law for the Implementation of the Integrated System of Interventions and Social Services” [“Legge Quadro Per La Realizzazione del Sistema Integrato Di Interventi e Servizi Sociali”]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Italian H.M. Rehabilitation national plan: An Italian act. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 47, 621–638. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. From patient to Citizen–A national action plan for the disability policy [Från patient till Medborgare–En nationellhandlingsplan för handikapp.olitiken]; Ministry of Health: Stockhom, Sweden, 2000.

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Federal Act on Participation [Gesetz zur Stärkung der Teilhabe und Selbstbestimmung von Menschen mit Behinderungen (Bundesteilhabegesetz–BTHG); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, A.B.; Gutenbrunner, C.; Damjan, H.; Giustini, A.; Delarque, A. European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) section of physical and rehabilitation medicine: A position paper on physical and rehabilitation medicine in acute settings. J. Rehabili. Med. 2010, 42, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, A.B.; Gutenbrunner, C.; Giustini, A.; Delarque, A.; Fialka-Moser, V.; Kiekens, C.; Berteanu, M.; Christodoulou, N. A position paper on Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine programmes in post-acute settings Union of European Medical Specialists Section of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (in conjunction with the European Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine). J. Rehabili. Med. 2012, 44, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Rapidi, C.A.; Tederko, P.; Moslavac, S.; Popa, D.; Aguiar Branco, C.; Kiekens, C.; Varela Donoso, E.; Christodoulou, N. Evidence based position paper on Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM) professional practice for persons with spinal cord injury. The European PRM position (UEMS PRM Section). Eur. J. Phys. Rehabili. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Corrà, U.; Benzer, W.; Bjarnason-Wehrens, B.; Dendale, P.; Gaita, D.; McGee, H.; Mendes, M.; Niebauer, J.; Zwisler, A.D.; et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabili. 2010, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. CSP COVID-19 Rehabilitation Standards; Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Paul, O. Germany Passes Federal Law for the Participation of Disabled People. Available online: https://legal-dialogue.org/v-germanii-prinyat-federalnyj-zakon-o-sodejstvii-lyudyam-s-ogranichennymi-vozmozhnostyami (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- OECD. Sickness and Disability Schemes in the Netherlands: Country Memo as a Background Paper for the OECD Disability Review. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/social/soc/41429917.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in Health Systems: Guide for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Skempes, D.; Melvin, J.; von Groote, P.; Stucki, G.; Bickenbach, J. Using concept mapping to develop a human rights based indicator framework to assess country efforts to strengthen rehabilitation provision and policy: The Rehabilitation System Diagnosis and Dialogue framework (RESYST). Glob. Health 2018, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. Offender Rehabilitation Act (c. 11), United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2014.

- National Assembly for Wales. The Local Health Boards (Functions) (Wales) Regulations; National Assembly for Wales: Deeside, Wales, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parliamentary Under Secretary of State. Health Act 1999 (Commencement No. 17) Order 2017; Parliamentary Under Secretary of State: London, UK, 2017.

- Secretary of State for Health. The Health Act 1999 (Consequential Amendments) (Nursing and Midwifery) Order 2004; Government of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2004.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. The Independent Health Care Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2005; Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety: Belfast, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. Equality Act, United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2010.

- Parliament of the United Kingdom. Community Care (Delayed Discharges etc.) Act 2003 (c. 5), United Kingdom; Parliament of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2003.

- Scottish Ministers. The National Health Service Superannuation Scheme (Scotland) Regulations 2011, Scotland; The Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK.

- The Italian Republic. Ministerial Decree No 182 of 29 March 2001: Regulation Concerning the Identification of the Figure of the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Technician [D.M. 29 marzo 2001, n. 182: Regolamento Concernente La Individuazione Della Figura Del Tecnico Della Riabilitazione Psichiatrica]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Republic. Law No. 284: Provisions for the Prevention of Blindness and for the Visual Rehabilitation and Social and Occupational Integration of the Blind Multiminor [Legge 28 agosto 1997, n. 284: “Disposizioni per La Prevenzione Della Cecità e per La Riabilitazione Visiva e L’integrazione Sociale E Lavorativa dei Ciechi Pluriminorati”]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Republic. Law No. 279: Regulation for the Establishment of the National Network of Rare Diseases and Exemption from Participation in the Cost of the Related Health Services Pursuant to Article 5(1)(b) of Legislative Decree no 124 of 29 april 1998 [“Regolamento di Istituzione Della Rete Nazionale Delle Malattie Rare e di Esenzione Dalla Partecipazione Al Costo Delle Relative Prestazioni Sanitarie Ai Sensi Dell’articolo 5, Comma 1, Lettera b) del Decreto Legislativo 29 Aprile 1998, n. 124.”]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Republic. Law No. 332: Regulation Containing Rules for the Provision of Prosthetic Assistance within the National Health Service: Method of Provision and Rates [“Regolamento Recante Norme Per Le Prestazioni Di Assistenza Protesica Erogabili Nell’ambito Del Servizio Sanitario Nazionale: Modalità Di Erogazione e Tariffe.”]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Republic. Law no. 18 of 3 March 2009: “Ratification And Implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with Optional Protocol, Done in New York On 13 December 2006 and Establishment of the National Observatory on the Condition of Persons with Disabilities” [“Ratifica Ed Esecuzione Della Convenzione Delle Nazioni Unite Sui Diritti Delle Persone Con Disabilità, Con Protocollo Opzionale, Fatta a New York Il 13 Dicembre 2006 e Istituzione Dell’osservatorio Nazionale Sulla Condizione Delle Persone Con Disabilità”]; Official Gazette [Gazzetta Ufficiale (GU)]: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Sweden. Law Amending the Health and Medical Services Act [SFS 2003:194 Lag om ändring i hälso-och sjukvårdslagen (1982:763)]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2003.

- Government of Sweden. Law Amending the Health and Medical Services Act [SFS 2018:143 Lag om ändring i hälso- och sjukvårdslagen (2017:30)]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

- Government of Sweden. Act (1993:387) concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 1993.

- Government of Sweden. Assistance Benefit Act (No. 389) [Lag (1993:389) om assistansersättning]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 1993.

- Government of Sweden. Regulation No. 526 on State Authorities Responsibility for Implementing Disability Policy [ Förordning (2001:526) om de statliga myndigheternas ansvar för genomförande av funktionshinderspolitiken]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2001.

- Government of Sweden. Discrimination Act (2008:567) [ Diskrimineringslag (2008:567)]; Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS): Stockholm, Sweden, 2008.

- The Government and the States General. Patients’ Rights (Care Sector) Act [ Wet Cliëntenrecht zorg]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011.

- The Government and the States General. Youth Act [Jeugdwet]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014.

- The Government and the States General. Public Health Act [Wet publieke gezondheid]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2008.

- The Government and the States General. Healthcare Insurance Act (Zorgverzekeringswet); The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005.

- The Government and the States General. Long-Term Care Act (Wet langdurige zorg); The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014.

- The Government and the States General. Social Supp.ort Act (Wet maatschapp.elijke ondersteuning); The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015.

- The Government and the States General. Individual Health Care Professions Act (Wet op de beroepen in de individuele gezondheidszorg); The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1993.

- The Government and the States General. Chronically Ill and Disabled Persons (Allowances) Act [Wet tegemoetkoming chronisch zieken en gehandicapten (WTCG)]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2008.

- The Government and the States General. Health Care Allowance Act (Wet op de zorgtoeslag); The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005.

- The Government and the States General. Health Care Market Regulation Act [Wet Marktordening Gezondheidszorg]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2006.

- The Government and the States General. Health Care Tariffs Act [Wet tarieven gezondheidszorg]; The Government and the States General: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1980.

- Federal Ministry of Health. Second Bill to Strengthen Long-Term Care; Federal Ministry of Health: Bonn, Germany, 2015.

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Health Care Structure Act (Gesundheitsstrukturgesetz, GSG); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGB1)]. SHI Reform Act (Zweites GKV-Neuordnungsgesetz); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGB1)]: Bonn, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Health Care Reform Act (GKV-Gesundheitsreformgesetz); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGB1)]. Risk Structure Compensation Reform Act (Gesetz zur Reform des Risikostrukturausgleich); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGB1)]: Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Act to strengthen competition within SHI (GKV-Wettbewerbsstärkungsgesetz, GKV-WSG); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Law on the structural further development of nursing care insurance (Pflege-Weiterentwicklungsgesetz); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Act on the Further Development of Organizational Structures in Statutory Health Insurance (GKV-OrgWG); Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Disability Equality Act [Gesetz zur Gleichstellung von Menschen mit Behinderungen (Behindertengleichstellungsgesetz–BGG)]; Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. General Equal Treatment Act [Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz(AGG)]; Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]. Social Code Book V [Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch (V)–Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung–(Artikel 1 des Gesetzes v. 20. Dezember 1988, BGBl. I S. 2477)]; Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBl)]: Bonn, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Strategic Plan for the Next four Years: Better Outcomes by 2020; Public Health England: London, UK, 2016; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. NHS Outcomes Framework: At-A-Glance; Department of Health: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England. The NHS Five Year Forward View; 2014; NHS England: Leeds, UK, 2014; pp. 2–36. [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes UK. Tackling the Diabetes Crisis Together: Our Ambition to 2019; Diabetes UK: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Taskforce. Five Year Forward View for Mental Health; Mental Health Taskforce: London, UK, 2016; pp. 4–70. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Social Care. Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020: Implementation Plan; Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2016; pp. 3–78. [Google Scholar]

- Great Britain, Office for Disability Issues. Roadmap 2025: Achieving Disability Equality by 2025; Office for Disability Issues: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England/Policy Directorate/Business Planning Team. NHS England’s business plan 2014/15–2016/17: Putting Patients First; NHS England: Leeds, UK, 2014; pp. 7–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chief Allied Heath Professions Officer’s Team. AHPs into Action. Using Allied Health Professions to Transform Health, Care and Wellbeing; NHS England: Leeds, UK, 2017; pp. 4–47. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. The UK Strategy for Rare Diseases; Department of Health: London, UK, 2013; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- NAMSE. National Plan of Action for People with Rare Diseases: Action Fields, Recommendations, and Proposed. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/N/NAMSE/National_Plan_of_Action.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- DEval: German Institute for Development Evaluation. Action plan for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (concluded). Available online: https://www.deval.org/en/action-plan-for-the-inclusion-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- Working Group on Rehabilitation at the Ministry of Health (Gruppo di Lavoro sulla Riabilitazione at Ministero della Salute). Rehabilitation Guidance Plan [Piano d’indirizzo per la Riabilitazione]; Ministry of Health: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 18.

- National Action Plan for Mental Health [Piano di azioni nazionale per la salute mentale]. Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1905_allegato.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2018).

- National Plan of Chronicity [Piano Nazionale della Cronicità]. Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2584_allegato.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2018).

- Di Fiandra, T.; Canevelli, M.; Di Pucchio, A.; Vanacore, N. The Italian dementia national plan commentary. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2015, 51, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Ministry of Health [Ministero della Salute]. The Italian Dementia National Plan [Piano nazionale demenze]; Italian Ministry of Health: Rome, Italy, 2014.

- Outcome Based Healthcare 2018–2022. Available online: https://www.government.nl/ministries/ministry-of-health-welfare-and-sport/documents/reports/2018/07/02/outcome-based-healthcare-2018-2022 (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- Strategic Policy Plan CVON 2015–2020 [strategisch Beleidsplan CVON 2015–2020]. Available online: https://www.hartstichting.nl/getmedia/b58d8063-f2b0-480b-b78d-197947eefbab/strategie-beleidsdocument-cvon.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- VUmc Alzheimer Centre; National umbrella organisation of medical university hospitals [Nederlandse Federatie Van Universitair Medische Centra] (NFU). Delta Plan for Dementia [Deltaplan Dementie]. Available online: https://www.neurodegenerationresearch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/rapport-deltaplan-dementie.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Alzheimer Europe. 2012: National Dementia Strategies (diagnosis, treatment and research). Available online: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Policy-in-Practice2/Country-comparisons/2012-National-Dementia-Strategies-diagnosis-treatment-and-research/Netherlands (accessed on 5 January 2019).

- Diabetes until 2025: Prevention and Care in Coherence [Diabetes tot 2025: Preventie en zorg in samenhang]. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/260322004.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ministry of Health and Social Affairs [Government Offices of Sweden]. Dementia strategy focusing on care. Available online: https://www.government.se/articles/2018/07/dementia-strategy-focusing-on-care/ (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen). National Guidelines for Multiple Sclerosis Care [Nationella riktlinjer för vård vid multipel skleros (MS)]; National Board of Health and Welfare: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; p. 435. [Google Scholar]

| United Kingdom | Sweden | Germany | Italy | Netherlands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare model type | Anglo-Saxon/Liberal | Nordic/Social Democratic | Continental/ Conservative | Mediterranean | Continental/ Conservative |

| Healthcare system model | Beveridge | Beveridge | Bismarck | Beveridge/Mixed | Bismark/Mixed |

| Subregion | Northern/ Nordic | Northern/ Nordic | Continental Europe | Southern Europe | Continental Europe |

| Characteristics | National Health Service System funded through general taxation | National health care system funded through general tax revenues; regulation, supervision, and some funding through national government; responsibility for most financing/purchasing/provision devolved to county councils | Statutory health insurance system; system funded through employer/ employee earmarked payroll tax and general taxation | National health care system funded by national earmarked corporate and value-added taxes as well as general/regional taxation; funding and minimum benefit package defined by national government; planning and provision by regions | Statutory health insurance system, with universally mandated private insurance; funded through earmarked payroll tax; community-rated insurance premiums; general tax revenue |

| Extensive network (mainly private) of primary care providers | Mixed primary care system (40% private, 60% public) | Private primary care system | Private primary care system | Private primary care system | |

| No cap on cost sharing Drug cost-sharing exemptions | Caps on cost sharing (Annual maximum for outpatient visits is SEK 1,150 (USD 125); for drugs, SEK 2,250 (USD 246) for adults); Some cost sharing exemptions | Cap on cost sharing (2% of household income, 1% of income for chronically ill); children and adolescents <18 years of age exempt | No cap on cost sharing; exemptions for low-income older people/children, pregnant women, chronic conditions/disabilities, rare diseases | No cap on cost sharing; annual deductible of 385 Euros covers most cost sharing; general practitioner care and children exempt from cost-sharing; | |

| Key Indicators (2016) | |||||

| Healthy Life Years at age 65 (men, women) | 10.4 | 15.1 | 11.5 | 10.4 | 10.3 |

| 11.1 | 16.6 | 12.4 | 10.1 | 9.9 | |

| Population aged 65 and more (%) | 17.9 | 19.8 | 21.1 | 22 | 18.2 |

| Self-reported chronic morbidity(%) a | 36 | 37.6 | 42.3 | 15.2 | 33 |

| Rehabilitation expenditure per capita (PPS) | n/a | n/a | 117.8 | n/a | 168.3 |

| Rehabilitation beds/1000 population | n/a | n/a | 2.01 | 0.41 | 0.11 |

| Practicing physiotherapists/100,000 population | 44.49 (2014) | 129.2 (2012) | 207.8 (2013) | 93.88 (2013) | 192.4 (2013) |

| Legislations | Policies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Type | Enacted legislation detailing financial and institutional arrangements on health service coverage/delivery | Laws on human research | Action plans, strategies, and policies addressing the following target groups: | Action plans focusing only on prevention of noncommunicable diseases |

| ||||

| Laws on data protection including regulations regarding the protection of privacy and confidentiality of health information | Action plans, strategies, and policies addressing other aspects of health service delivery such as e-health/digital health | |||

| Action plans, strategies and policies addressing the following programmatic areas within the health system, including: | ||||

| Laws and regulations on health professional practice and education |

| |||

| Environmental health laws | Intersectoral action plans on disability (i.e., national strategies for the inclusion/integration of disabled persons) | |||

| Food laws | Sectoral or multisectoral action plans on rehabilitation | |||

| Submitted bills, upcoming bills, law proposals, national constitutions | ||||

| Timeframe | 1980–2018 | Pre-1980 | Action plans, strategies and policies that are currently under implementation or were implemented within the last three years, i.e., implemented by 2015. | Action plans, strategies, and policies completed preceding 2015 |

| Level of implementation | National | Municipal, Regional | Action plans, strategies and policies at the national or federal level | Action plans, strategies and policies at regional, municipal, cantonal, and provincial levels |

| Languages | English, German, Swedish, Italian, Dutch | All languages not specified in inclusion criteria | English, German, Swedish, Italian, Dutch | All languages not specified in inclusion criteria |

| Countries | United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, Germany | All countries not specified in inclusion criteria | United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, Sweden, Germany | All countries not specified in inclusion criteria |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garg, A.; Skempes, D.; Bickenbach, J. Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning: A Concise Overview of Current Laws and Policies Addressing Access to Rehabilitation in Five European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124363

Garg A, Skempes D, Bickenbach J. Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning: A Concise Overview of Current Laws and Policies Addressing Access to Rehabilitation in Five European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124363

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarg, Aditi, Dimitrios Skempes, and Jerome Bickenbach. 2020. "Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning: A Concise Overview of Current Laws and Policies Addressing Access to Rehabilitation in Five European Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124363

APA StyleGarg, A., Skempes, D., & Bickenbach, J. (2020). Legal and Regulatory Approaches to Rehabilitation Planning: A Concise Overview of Current Laws and Policies Addressing Access to Rehabilitation in Five European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124363