Caregivers’ Experience of Caring for a Family Member with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Content Analysis of Longitudinal Social Media Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. ADLs, Caregiver Burden and Social Media Support

2.1. ADLs and Its Classification

2.2. Dementia Caregiver Burden

2.3. Caregiver Support through the Social Media

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Content Analysis in Social Media Environment

- (A) Basic ADLs [27]

- (1) Bathing and showering; (2) Personal hygiene (excluding 1); (3) Dressing; (4) Toilet hygiene; (5) Transferring (mobility within the house); (6) Self-feeding, eating/drinking (including chewing and swallowing); (7) Communication and interaction.

- (B) Instrumental ADLs [28]

- (1) Cleaning and maintaining the house; (2) Managing money; (3) Moving within the community (outside the house/the family); (4) Preparing meals; (5) Shopping; (6) Taking prescribed medications; (7) Using the telephone, computer and online communication; (8) Entertainment (e.g., movies, music, books, pictures, videos); (9) Physical activities, sports.

- (C) Extended ADLs [29]

- (1) Selection of caregivers and health facilities, moving to a facility; (2) Care of pets; (3) Safety procedures and emergency responses; (4) Sleeping disorders, including sundowning; (5) Religious observances, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries; (6) Health management, maintenance and prevention; (7) Social groups and other public events; (8) Ageing, death and dying; (9) Getting help (especially from family members); (10) Appointments, tests, surgeries.

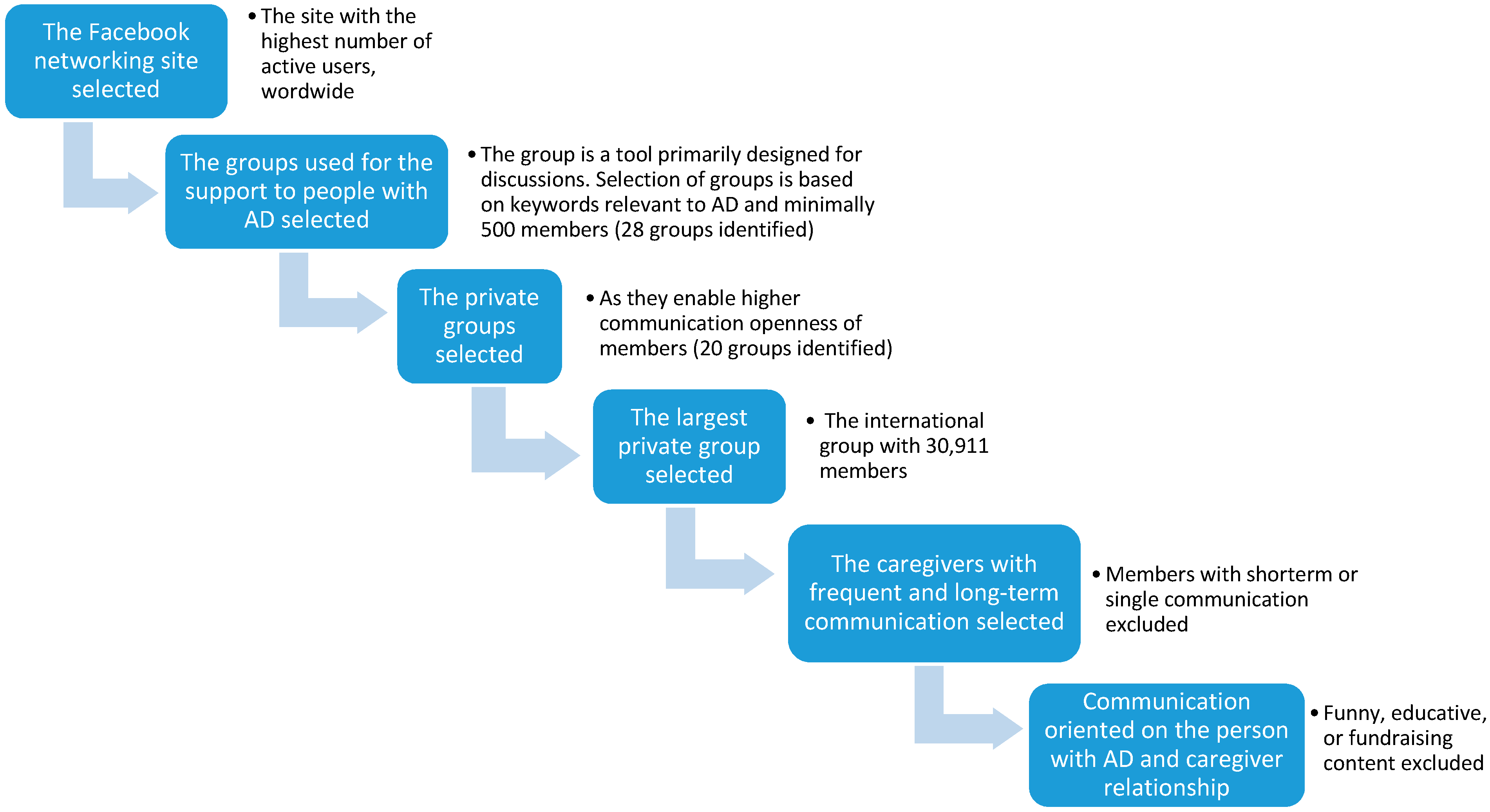

3.2. The Sampling Strategy

3.3. The Sample Characteristics

3.4. Data Collection, Processing and Inter-Coders Reliability

3.4.1. Data Collection

3.4.2. Data Processing

3.4.3. Inter-Coders Reliability

3.4.4. Ethical Aspect of Data Collection and Processing

4. Results

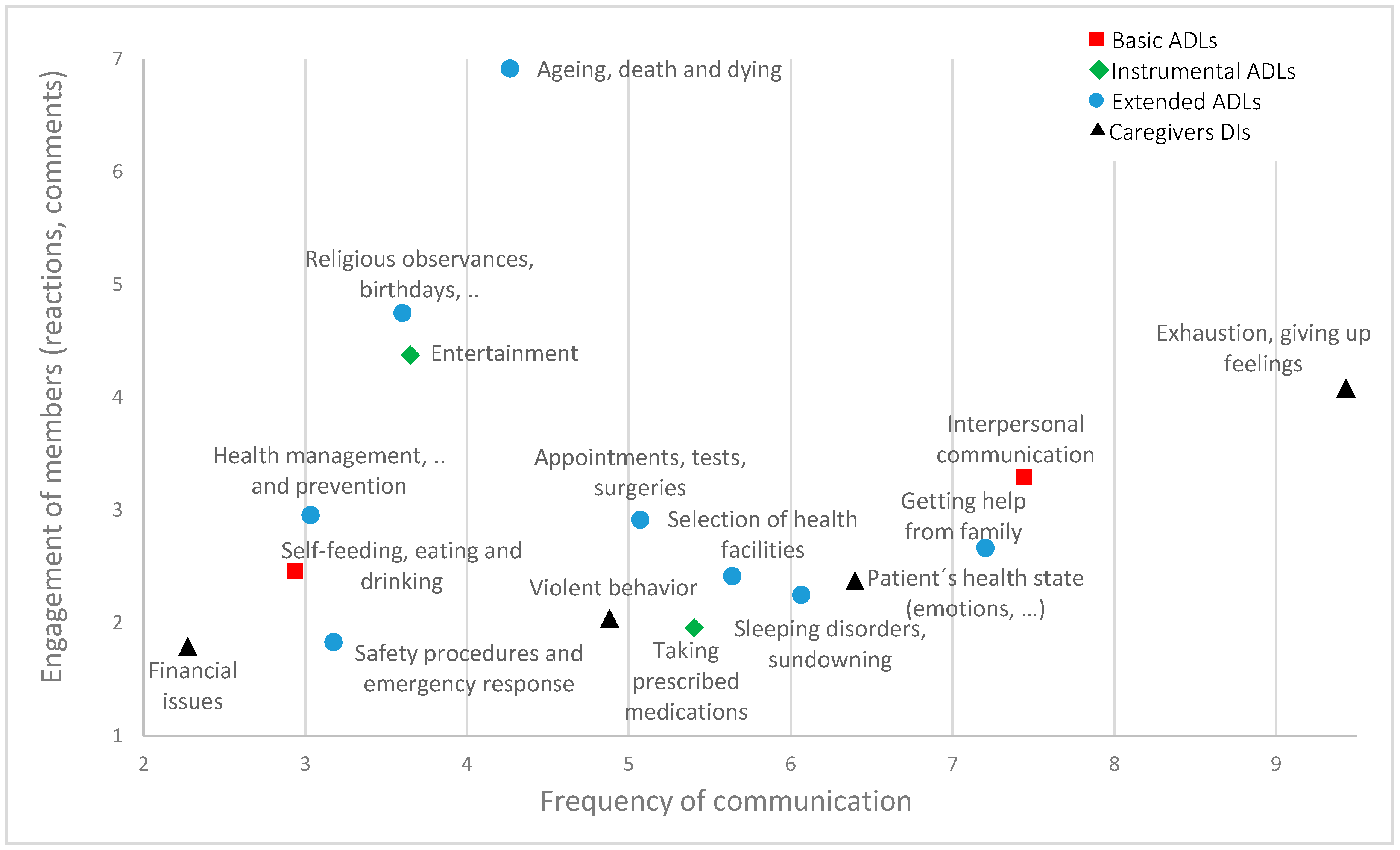

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Individual Categories

4.2. Discussion Topics Related to Basic ADLs

4.2.1. Quantitative Dimension

4.2.2. Qualitative Dimension

4.3. Discussion Topics Related to IADLs

4.3.1. Quantitative Dimension

4.3.2. Qualitative Dimension

4.4. Discussion Topics Related to EADLs

4.4.1. Quantitative Dimension

4.4.2. Qualitative Dimension

4.5. Discussion Topics Related to Caregiver’s Daily Issues

4.5.1. Quantitative Dimension

4.5.2. Qualitative Dimension

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2017. World Population Projected to Reach 9.8 Billion in 2050, and 11.2 Billion in 2100. 21 June 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2017.html (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Quinn, M.M.; Markkanen, P.K.; Galligan, C.J.; Sama, S.R.; Kriebel, D.; Gore, R.J.; Brouilette, N.M.; Okyere, D.; Sun, C.; Punnett, L.; et al. Occupational health of home care aides: Results of the safe home care survey. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 73, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbakel, E. How to understand informal caregiving patterns in Europe? The role of formal long-term care provisions and family care norms. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePasquale, N.; Davis, K.D.; Zarit, S.H.; Moen, P.; Hammer, L.B.; Almeida, D.M. Combining formal and informal caregiving roles: The psychosocial implication of double- and triple-duty care. J. Gerontol. Ser. B-Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crous-Bou, M.; Minguillón, C.; Gramunt, N.; Molinuevo, J.L. Alzheimer’s disease prevention: From risk factors to early intervention. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2017, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer Disease International. The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Pervalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends; World Alzheimer Report; Alzheimer Disease International: London, UK, 2015; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa, C.; Thompson, P.L.; van Walsem, A.; Faure, C.; Maier, W.C. Epidemiological and economic burden of Alzheimer’sdisease: A systematic literature review of data across Europe and the United States of America. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 43, 1271–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitaliano, P.P.; Ustundag, O.; Borson, S. Objective and subjective cognitive problems among caregivers and matched non-caregivers. Gerontolist 2017, 57, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marešová, P.; Mohelská, H.; Dolejš, J.; Kuča, K. Socio-economic aspects of Alzheimer´s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravevski, E.; Lameski, P.; Trajkovik, V.; Kulakov, A.; Chorbev, I.; Goleva, R.; Pombo, N.; Garcia, N. Improving activity recognition accuracy in ambient assisted living systems by automated feature Engineering. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 5262–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindrod, K.A.; Li, M.; Gates, A. Evaluating user perceptions of mobile medication management applications with older adults: A usability study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2014, 2, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, R.; Werner, S.; Auslander, G.K.; Shoval, N.; Heinik, J. Attitudes of family and professional care-givers towards the use of GPS for tracking patients with dementia: An exploratory study. Br. J. Sociol. 2009, 39, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Digital Report 2019. Q4 Update Valid to October 2019. Available online: https://hootsuite.com/pages/digital-in-2019 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- LaCoursiere, S.P. A theory of online social support. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2001, 24, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelker, L.S.; Browdie, R.; Sidney Katz, M.D. A New Paradigm for Chronic Illness and Long-Term Care. Gerontolist 2014, 54, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, P.M.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Gerontolist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. Consideration of Function & Functional Decline. In Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Geriatrics, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-07-179208-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mlinac, E.M.; Feng, M.C. Assessment of Activities of Daily Living, Self-Care, and Independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookman, A.; Harrington, M.; Pass, L.; Reisner, E. Family Caregiver Handbook; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Roley, S.S.; DeLany, J.V.; Barrows, C.J.; Brownrigg, S.; Honaker, D.; Sava, D.I.; Talley, V.; Voelkerding, K.; Amini, A.D.; Smith, E.; et al. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain & practice framework, 2nd edition. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2008, 62, 625–683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Na, R.; Yang, J.H.; Yeom, Y. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Nonpharmacological Interventions for Moderate to Severe Dementia. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodaty, H.; Arasaratnam, C. Meta-analysis of Nonpharmacological Interventions for Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olazaran, J.; Reisberg, B.; Clare, L.; Cruz, I.; Pena-Casanova, J.; del Ser, T.; Woods, B.; Beck, C.; Auer, S.; Lai, C.; et al. Nonpharmacological Therapies in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Efficacy. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2010, 30, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henskens, M.; Nauta, I.M.; van Eekeren, M.C.A.; Scherder, E.J.A. Effects of Physical Activity in Nursing Home Residents with Dementia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2018, 46, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.F.; Jiang, T.; Cao, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Tan, C.-C.; Meng, X.-F.; Tan, L.; et al. Physiotherapy Intervention in Alzheimer’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 44, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, S.; Laver, K.; Voigt-Radloff, S.; Letts, L.; Clemson, L.; Graff, M.; Wiseman, J.; Gitlin, L. Occupational therapy for people with dementia and their family carers provided at home: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehling, T.; Sixsmith, J.; Corr, S.; Pilkington, A.; Chard, G. Occupational therapy perspectives on cognitive stimulation therapy: In relation to activities of daily living (ADL). Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 80 (Suppl. 8), 30. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X. Do nonpharmacological interventions prevent cognitive decline? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-T. Dementia Caregiver Burden: A Research Update and Critical Analysis. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep. 2017, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isik, A.T.; Soysal, P.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N. Bidirectional relationship between caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A narrative review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2019, 34, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongisto, K.; Hallikainen, I.; Selander, T.; Törmälehto, S.; Väätäinen, J.; Martikainen, J.; Välimäki, T.; Hartikainen, S.; Suhonen, J.; Koivisto, A.M. Quality of Life in relation to neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: 5-year prospective ALSOVA cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.; Barrett, A.; Lebrec, J.; Dodel, R.; Jones, R.W.; Vellas, B.; Wimo, A.; Argimon, J.M.; Bruno, G.; Haro, J.M. How useful is the EQ-5D in assessing the impact of caring for people with Alzheimer’s Disease? Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.M.; McQuiggan, M.; Williams, V.; Westervelt, H.; Tremont, G. Burden among spousal and child caregivers of patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2008, 25, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Lee, J.; Bakker, T.J.E.M.; Duivenvoorden, H.J.; Dröes, R.-M. Multivariate Models of Subjective Caregiver Burden in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, D.P.; Patil, S.; Benson, J.J.; Gage, A.; Washington, K.; Kruse, R.L.; Demiris, G. The Effect of Internet Group Support for Caregivers on Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Caregiver Burden: A Meta-Analysis. Telemed. E-Health 2017, 23, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, C.; Giebel, C.; Bleijlevens, M.; Lethin, C.; Stolt, M.; Saks, K.; Soto, M.E.; Meyer, G.; Zabalegui, A.; Chester, H.; et al. Caring for a Person with Dementia on the Margins of Long-Term Care: A Perspective on Burden from 8 European Countries. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, F.L.; Heinrich, S.; Wolf-Ostermann, K.; Schmidt, S.; Thyrian, J.R.; Schäfer-Walkmann, S.; Holle, B. Caregiver burden assessed in dementia care networks in Germany: Findings from the DemNet-D study baseline. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Jin, Y.; Shi, Z. The effects of behavioral and psychological symptoms on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical experience in China. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: A meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallim, A.B.; Sayampanathan, A.A.; Cuttilan, A.; Ho, R. Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.W.; Feld, S.; Dunkle, R.E.; Schroepfer, T.; Lehning, A. The prevalence of older couples with ADL limitations and factors associated with ADL help receipt. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2015, 58, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaingankar, J.A.; Chong, S.A.; Abdin, E.; Pico, L.; Jeyagurunathan, A.; Zhang, Y.; Sambasivam, R.; Chua, B.Y.; Ng, L.L.; Prince, M.; et al. Care participation and burden among informal caregivers of older adults with care needs and associations with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savundranayagam, M.Y.; Montgomery, R.J.; Kosloski, K. A dimensional analysis of caregiver burden among spouses and adult children. Gerontologist 2010, 5, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, B.S.; Johnston, D.; Rabins, P.V.; Morrison, A.; Lyketsos, C.; Samus, Q.M. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: Findings from the Maximizing Independence at Home study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, R.E.; Feld, S.; Lehning, A.J.; Kim, H.; Shen, H.-W.; Kim, M.-H. Does becoming an ADL spousal caregiver increase the caregiver’s depressive symptoms? Res. Aging 2014, 36, 655–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.G.; Hundt, E.; Dean, M.; Keim-Malpass, J.; Lopez, R.P. “The Church of Online Support”: Examining the Use of Blogs among Family Caregivers and Persons With Dementia. J. Fam. Nurs. 2017, 23, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, M.P.; Chisholm, A.; Shulhan, J.; Milne, A.; Scott, D.S.; Given, L.M.; Hartling, L. Social media use among patients and caregivers: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventola, C.L. Social Media and Health Care Professionals: Benefits, Risks, and Best Practices. P&T J. Formul. Manag. 2014, 39, 491–499. [Google Scholar]

- Smailhodzic, E.; Hooijsma, W.; Boonstra, A.; Langley, D.J. Social media use in healthcare: A systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedin, T.; Al Mamun, M.; Lasker, M.A.A.; Ahmed, S.W.; Shommu, N.; Rumana, N.; Turin, T.C. Social Media as a Platform for Information About Diabetes Foot Care: A Study of Facebook Groups. Can. J. Diabetes 2017, 41, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretorius, C. Die ervaring van aktiewe betrokkenheid by ʼn aanlyn Facebook-ondersteuningsgroep as ʼn vorm van ondersteuning vir individue wat met Meervoudige Sklerose gediagnoseer is. Tydskr. Geesteswet. 2016, 56, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, D.A.; Brady, E.; Yi, E.-H.; Bateman, D.R. Friendsourcing Peer Support for Alzheimer’s Caregivers Using Facebook Social Media. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2018, 36, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, D.R.; Brady, E.; Wilkerson, D.; Yi, E.-H.; Karanam, Y.; Callahan, C.M. Comparing Crowdsourcing and Friendsourcing: A Social-Media Feasibility Study to Support Alzheimer Disease Caregivers. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, J.M.; Johnson, T.W.; Hennessey, C.; Beattie, B.L.; Illes, J. Aging 2.0: Health Information about Dementia on Twitter. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, M.P.; Shavi, K.; Gates, A.; Fernandes, R.M.; Scott, S.D.; Hartling, L. Which outcomes are important to patients and families who have experienced paediatric acute respiratory illness? Findings from a mixed methods sequential exploratory study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagervall, J.A.; Lag, M.L.; Brickman, S.; Ingram, R.E. Give a piece of your mind: A content analysis of a Facebook support group for dementia caregivers. Innov. Aging. 2019, 3, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.P. Basic Content Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.D.; Marsh, E.E. Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewson, C. Gathering Data on the Internet. Qualitative Approaches and Possibilities for Mixed Methods Research. In The Oxford Handbook of Psychology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 405–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piolat, A.; Olive, T.; Kellogg, R.T. Cognitive effort during note taking. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 23, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, P. Citizens’ Engagement on Regional Governments’ Facebook Sites. Empirical Research from the Central Europe. Hradec Econ. Days 2019, 9, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Digital 2020: Global Digital Overview. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, Z.; Min, W. Finding Users’ Voice on Social Media: An Investigation of Online Support Groups for Autism-Affected Users on Facebook. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.C.; Lee, A.J.T.; Kuo, S.C. Mining Health Social Media with Sentiment Analysis. J. Med. Syst. 2016, 40, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfe, M.; Keohane, K.; O’Brien, K.; Sharp, L. Social networks, social support and social negativity: A qualitative study of head and neck cancer caregivers’ experiences. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsboe, E.; Terum, T.; Testad, I.; Aarsland, D.; Ulstein, I.; Corbett, A.; Rongve, A. Caregiver burden in family carers of people with dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2016, 31, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.P.; Curran, E.A.; Duggan, Á.; Cryan, J.F.; Chorcorain, A.N.; Dinan, T.G.; Molloy, D.W.; Kearney, P.M.; Clarke, G. A systematic review of the psychological burden of informal caregiving for patients with dementia: Focus on cognitive and biological markers of chronic stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 73, 123–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Helping Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: Which Interventions Work and How Large Are Their Effects? Int. Psychogeriatr. IPA 2006, 18, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Verbeek, H.; Janssen, B.M.; Eijkelenboom, A.; Molony, S.L.; Felix, E.; Nieboer, K.A.; Zwerts-Verhelst, E.L.M.; Sijstermans, J.J.W.M.; Wouters, E.J.M. A three perspective study of the sense of home nursing residents: The views of residents, care professionals, and relatives. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.; Froggatt, K.; Connolly, S.; O´Shea, E.; Sampson, E.L.; Casey, D.; Devane, D. Paliative care interventions in advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD0011513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.B.; Oyebode, J.R.; Owen, R.G. Consensus views on advance care planning for dementia: A Delphi study. Health Soc. Care Community 2016, 24, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepel, D. An Economic Perspective of Dementia Care in Ireland: Maximising Benefits and Maintaining Costs Efficiency; Policy Paper, I.; Alzheimer Society of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Category of ADLs | Posts | Average Reactions per Postt | Average Comments per Post | Average Total Engagement per Post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | % | ||||

| Bathing and showering | 19 | 5.8 | 43.5 | 14.3 | 57.8 |

| Personal hygiene | 18 | 5.5 | 38.2 | 10.8 | 49.0 |

| Dressing | 15 | 4.6 | 30.3 | 18.3 | 48.6 |

| Toilet hygiene | 30 | 9.2 | 27.7 | 30.9 | 58.6 |

| Transferring 1 | 20 | 6.2 | 12 | 11.4 | 23.4 |

| Self-feeding, eating/drinking 2 | 63 | 19.4 | 34.6 | 24.2 | 58.8 |

| Communication and interaction | 152 | 46.8 | 59.3 | 19.6 | 78.9 |

| In total for basic ADLs | 319 | 15.1 3 | 35.0 | 18.4 | 71.9 |

| Category of ADLs | Main Topics Discussed in the Category |

|---|---|

| Bathing and showering | Stress reducing toys during hair wash, refusing to wash (the whole body or a specific part), misconception of person with AD that they were already washed, positive feelings after washing, how to inform about it, recommended methods, fear of reactions when being told about washing. |

| Personal hygiene | Dental hygiene, new haircut, shaving, beard care. |

| Dressing | Struggles when putting underwear (particularly bra), dressing inappropriate for the weather, comfortable clothes, undressing. |

| Toilet hygiene | Stressfulness when diapers are rejected, control of bowel movement, diarrhoea and constipation, night incontinence, excretion outside the toilet, frequent change of bedding, physical difficulty of changing diapers. |

| Transferring 1 | Injuries caused by transfer, rejection of the use walkers or other mobility aids and its consequences, visual impairment. |

| Self-feeding, eating/drinking 2 | Insufficient diet, loss of appetite, over drinking (coffee, coke), overeating (in general, sugar), rejection of solid food, swallowing issues. |

| Communication and interaction with the patient | Missing of close voice, conversation, loss of sense of humour, loss of orientation in time, short-term return of conversation ability and answering, sighing/examples of nonsensical/funny conversations, informing what we plan to do in the future. |

| Category of IADLs | Posts | Average Reactions per Post | Average Comments per Post | Average Total Engagement per Post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | % | ||||

| Cleaning and maintaining the house | 22 | 7.4 | 22.5 | 13.5 | 36 |

| Managing money | 7 | 2.4 | 23.1 | 21.3 | 44.4 |

| Moving within the community 1 | 38 | 12.8 | 69.7 | 16.5 | 86.2 |

| Preparing meals | 21 | 7.1 | 32.3 | 42.7 | 75 |

| Shopping | 4 | 1.3 | 35.5 | 28.5 | 64 |

| Taking prescribed medications | 114 | 38.4 | 18.2 | 28.8 | 47 |

| Using the phone, computer and online communication | 7 | 2.4 | 28.1 | 16.7 | 44.8 |

| Entertainment 2 | 77 | 25.9 | 82.8 | 21.8 | 104.6 |

| Physical activities, sports | 7 | 2.4 | 24.3 | 17.4 | 41.7 |

| In total for IADLs | 297 | 16.0 3 | 37.4 | 23.1 | 83.7 |

| Category of Daily Life Activity | Main Topics Discussed in the Category |

|---|---|

| Cleaning and maintaining the house | Lack of self-cleaning, cleaning in a confused way (storing of objects in strange places, mismatching of socks), unwillingness to get rid of objects, wrong time for cleaning. |

| Managing money | Bank account transfer on other persons, accusation by the person with AD from stealing money. |

| Moving within the community 1 | Visiting local shops, cafes, museums, manicure, games, etc., and its impact on the behaviour, common eating outside the home, trips, and holidays (from one to several days), discussions on ability to drive. |

| Preparing meals | Composition and nutritional value of food, variety of dishes, food quality verification, recommendations for new “soft” or liquid/puree food (in later stages of disease); providing a varied diet, selection of machine to puree foods, recipes for good foods and drinks. |

| Shopping | Caregiver’s stress when shopping together (watching many things at once), loss of place orientation when shopping. |

| Taking prescribed medications | Effects (including side effects) of prescribed medication (Memantime, Zoloft, Risperidone, Donepezil, Xanax, Aricept), risks of specific alternative drugs (mainly CBD oil, cannabis), change of medication and its impact, troubles with swallowing medicine. |

| Using the phone, computer and online communication | Excessive costs caused by calls, discussions on virtual assistants (Alexa), advantage of Skype for distant conversation, repetitive, repeated calls (50 times a day) or nonsensical calls from the person with AD. |

| Entertainment 2 | Positive effects of music listening on a patient, use of headphones, share of selfies/videos with patient, cinema visits, video recording together, recommendations on good movies, playing music instrument by person with AD, family picture time, iPod games. |

| Physical activities, sports | Surprise over good sport performance of the person with AD, resistance to return to sports. |

| Category of EADLs | Posts | Average Reactions per Post | Average Comments per Post | Average Total Engagement per Post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | % | ||||

| Selection of caregivers and health facilities, moving to a facility | 119 | 13.6 | 35.0 | 23.4 | 58.4 |

| Care of pets | 18 | 2.1 | 33.8 | 11.8 | 45.6 |

| Safety procedures and emergency responses | 67 | 7.6 | 25.9 | 17.8 | 43.7 |

| Sleeping disorders, sundowning | 128 | 14.6 | 36.1 | 18.5 | 54.6 |

| Religious observances, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries | 78 | 8.9 | 93.1 | 22.3 | 115.4 |

| Health management, maintenance and prevention | 64 | 7.3 | 39.8 | 31.0 | 70.8 |

| Social groups and other public events | 36 | 4.1 | 80.2 | 22.0 | 102.2 |

| Ageing, death and dying | 90 | 10.3 | 116.6 | 49.4 | 166.0 |

| Getting help 1 | 134 | 15.3 | 43.2 | 23.9 | 67.1 |

| Appointments, tests, surgeries | 124 | 14.5 | 35.1 | 28.7 | 63.8 |

| In total for instrumental ADLs | 858 | 40.7 2 | 54.0 | 24.9 | 103.8 |

| Category of EADLs | Main Topics Discussed in the Category |

|---|---|

| Selection of caregivers and health facilities, moving to a facility | Right time to place the person to facility, emotions/guilt associated with leaving to the facility (for both sides), selection of appropriate long-term/day care facility, waiting time for admission to the facility, health assessment/qualification for the level of care needed, change of the facility, beginnings in a new facility. |

| Care of pets | Significance of animals for patients, missing animals during their stay in a facility, animal death and its effect on the patient. |

| Safety procedures and emergency responses | Selecting bracelets/watches with GPS tracking (user friendly for patients), remote monitoring of physical activity, and coordination during use of a walker. Leaving a patient at home alone, patients’ escapes, concerns of caregivers when the person starts to walk again after a longer period on the bed, concerns related do the use of care and keeping car keys/driving license. Unexpected falls and its prevention. Safety in bathroom. |

| Sleeping disorders, sundowning | Persons wake up at night and start a daily routine; persons are several days without sleeping, effort to respect a sleeping schedule; concerns and discussions over “sleeping” medication. In lesser extent the sundowning issues and effects. |

| Religious observances, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries | Birthdays, Mother’s and Father’s Days, Marriage anniversaries, graduations in the family and other celebrations on the side of patient/caregiver/family. Positive feelings and behaviour of patients, effort to include patient in the selection of gifts. Celebrations with grandchildren. |

| Health management, maintenance and prevention | Management of caring activities and transfer of some works on other family members; concerns about the disease inheritance. Recommendations how to “cure”. How to recognize dementia/AD and diagnostics of disease. Efforts to increase patient independence. |

| Social groups and other public events | Activity groups, adult-day camps, activities of local Alzheimer’s organizations, fundraising events (walk/run) |

| Ageing, death and dying | Asking for support in hard, life threatening situations for patients. Discussions on “how much time do we have left”. Description of last life moments. Dilemma how to tell the other about the patient’s death. Memories on and love to the person who died. The joy of abandoning a miserable quality of life, asking for prayers and support. |

| Getting help 1 | Family disputes, controversies and no communication from the side of siblings/other relatives. Ineffectiveness of help from certain people living close. Help of other family members and its positive effect on the caregiver/person with AD. Help from the hospices and other (non-relatives) persons. |

| Appointments, tests, surgeries | Appointments to recognize patient’s needs, medication. Hospital tests for the disease stage. Surgeries after patient’s falls or injuries. Pros and cons of testing for AD predisposition. |

| Category of CDIs | Posts | Average Reactions per Post | Average Comments per Post | Average Total Engagement per Post | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | % | ||||

| Quality of health services | 18 | 3.1 | 43.8 | 42.7 | 86.5 |

| Change of a health state of the patient | 135 | 23.4 | 33.6 | 22.8 | 56.4 |

| Physical recognition of close relatives | 42 | 7.3 | 63.0 | 21.7 | 84.7 |

| Exhaustion, feeling of giving up, guilt | 200 | 34.7 | 59.4 | 39 | 98.4 |

| Fear of the future | 33 | 5.7 | 47.5 | 38.4 | 85.9 |

| Violent behaviour of the patient towards to caregiver | 103 | 17.9 | 28.2 | 21 | 49.2 |

| Caregiver’s success and positive feelings | 26 | 4.5 | 96.2 | 11.1 | 107.3 |

| Financial issues | 48 | 8.3 | 20.9 | 22.3 | 43.2 |

| Discussion group support and others | 33 | 5.7 | 42.9 | 37 | 79.9 |

| In total for CDIs | 638 | 30.2 1 | 48.4 | 28.4 | 76.8 |

| Category of Daily Life Activity | Main Topics Discussed in the Category |

|---|---|

| Quality of health services | Assessment of certified nurse assistance (CNA) quality, patient’s rejection of external services, complains on hospital services and its communication about the patient’s health state. |

| Change of a health state of the patient | Entering a new stage of the disease and coping with this new situation; associated emotions of caregivers. Patients (usually parents in the past) are becoming to be like children and children like parents. Description of a new specific health issue of the patient: physical (dry skin, rash, bedsores) and mental ones (agitation, frustration, murmuring, complaining teeth grinding, walking back and forth in the house). |

| Physical recognition of close relatives | Temporary or total non-recognition of a close person (life partner and children), forgetting the name. Comments on disappointment and other emotions associated. Fear of caregivers (often children) that they will not be recognized. |

| Exhaustion, feeling of giving up, guilt | Effects of caregiving activity performed 24/7 with no breaks, health issues of caregivers. Potential caregivers’ hostility towards the patient. Caregivers’ impossibility of having their “my time”. Loneliness. Guilt coming from not sufficient/successful work of caregivers (patient’s health state is not getting better). |

| Fear of the future | What the situation will look like in the future if the current situation is hard? Losing of personal life and time (relationships, hobbies, and friends) because of caregiving and fear of the future. Concerns about the future health state of the person with AD. |

| Violent behavior of the person with AD towards to the caregiver | Patient’s psychical (insults, cursing, shouting) and physical violence (hitting, throwing objects). The person with AD is rude when the caregiver wants to leave. Unexpected turns of person’s behaviour. |

| Caregiver’s success and positive feelings | Person’s thanks and love expression towards the caregivers. Finding pleasure in nature of caregiving work. Pleasure from the gifts received from the person with AD. |

| Financial issues | Absence/presence of medical/financial POA and/or patient’s will, communication between the person with AD and family about financial affairs, costs of health facilities and what is/is not covered by state medical care, paying of home health providers/caregivers, future concerns on financial matters. Accusations from patients/relatives about disuse of money; quarrel about money. Difficult financial family situations, tips on the ways of fundraising (for example crowdfunding) and proposals how to change a health insurance system. |

| Group support | Appreciation for group membership and support; opportunity to express emotions; get advice; resolve the situation; communicate with people who have the same problem, searching for someone in the group physically living nearby. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bachmann, P. Caregivers’ Experience of Caring for a Family Member with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Content Analysis of Longitudinal Social Media Communication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124412

Bachmann P. Caregivers’ Experience of Caring for a Family Member with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Content Analysis of Longitudinal Social Media Communication. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124412

Chicago/Turabian StyleBachmann, Pavel. 2020. "Caregivers’ Experience of Caring for a Family Member with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Content Analysis of Longitudinal Social Media Communication" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124412

APA StyleBachmann, P. (2020). Caregivers’ Experience of Caring for a Family Member with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Content Analysis of Longitudinal Social Media Communication. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124412