Guaranteed Equal Opportunities? The Access to Nursing Training in Central Europe for People with a Turkish Migration Background

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Professional Nursing in Austria

1.2. Migration and the Effects on the Population

1.3. Migration and Its Effects on Institutions

1.4. Migration and the Effects on Individuals

1.5. Research Questions

- (1)

- What are the experiences of experts in nursing training schools in Vorarlberg concerning people with a Turkish migration background during the admission procedure?

- (2)

- How do nurses and students with a Turkish migration background describe the admission procedure?

- (3)

- How is professional nursing seen by young people with a university entrance qualification and a Turkish migration background, and what are the attitudes of people in their social environment?

- (4)

- Which barriers can be derived and described on a micro-, meso-, and macro level according to the theory and the experiences of these three investigated groups?

1.6. Aim of the Study

2. Methods and Material

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Research Field

2.1.2. Access to the Research Field

2.2. Sample

2.3. Survey Method

2.4. Evaluation and Rating Method

3. Results

3.1. Admission Procedure

3.2. Individual Respondent’s Source of Information and Support for Choosing a Nursing Education

3.3. Interest and Motivation

3.4. Barriers

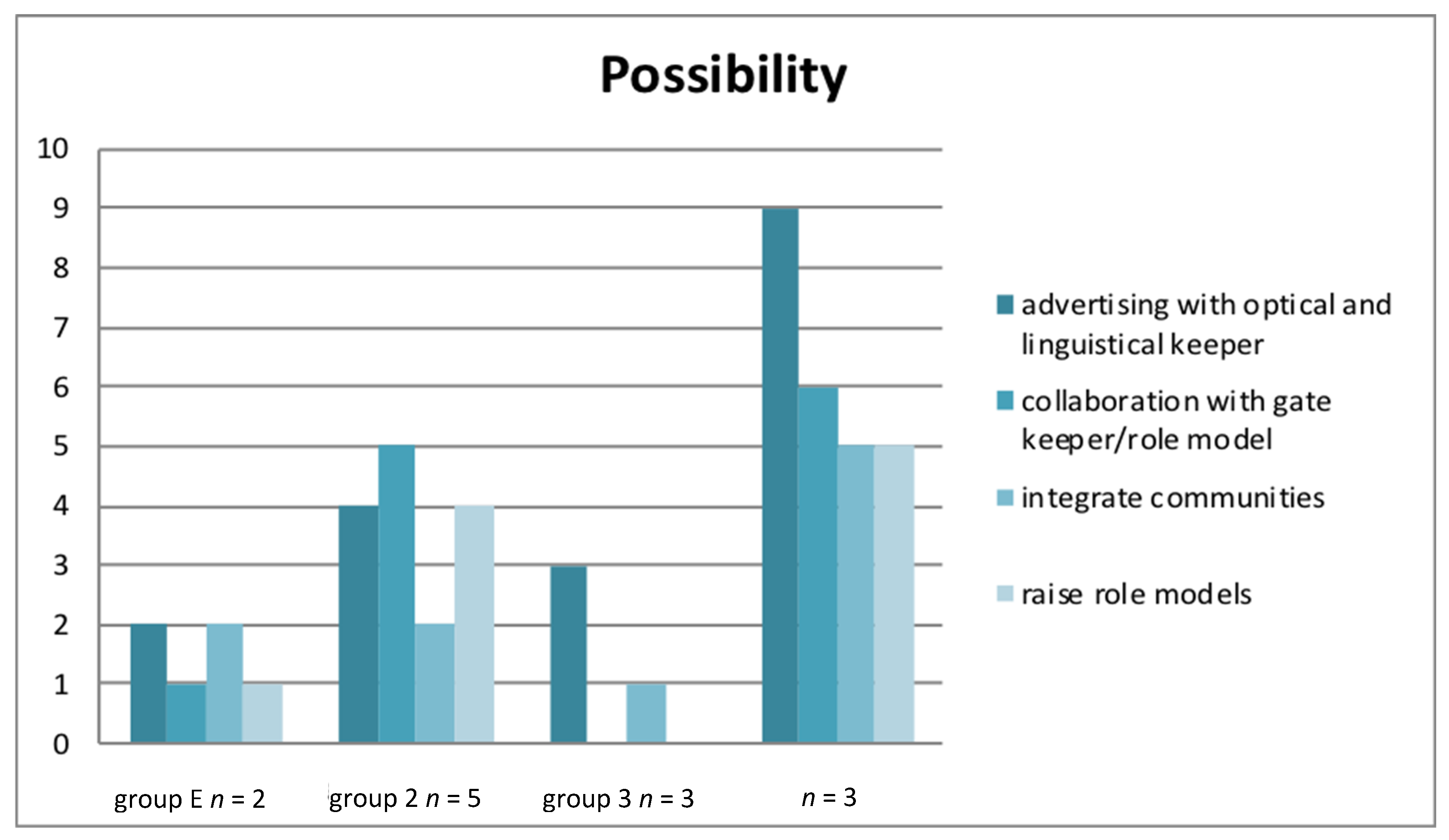

3.5. Possibilities to Overcome These Barriers

4. Discussion

4.1. Awareness of the Profession and Attitudes

4.2. Barriers

4.3. Possibilities to Increase the Number of Nurses with a Turkish Migration Background

4.4. Courses of Action

4.5. Experiences during Admission Procedure

4.6. Concluding Limitations, Strength and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statisik Austria. Chronische Krankheiten [Chronic Disease]. 2016. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/gesundheit/gesundheitszustand/chronische_krankheiten/index.html (accessed on 5 July 2017).

- Statisik Austria. Bevölkerungsstand und -Struktur [Level and Structure of Population]. 2017. Available online: www.statisik.at/web_de/statisiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/index.html (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Vorarlberg Steuert auf die 400.000 Einwohner-Marke zu. Available online: https://www.vol.at/vorarlberg-steuert-auf-die-400-000-einwohner-marke-zu/6499153. (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Bachinger, E.U.A. Wiener Sozialbericht 2015: Wiener Sozialpolitische Schriften Band 8. [Social Report of Vienna? 2015: Viennas Sociopolitical Writings Volume 8]. 2015, p. 223. Available online: http://www.wien.gv.at/gesundheit/einrichtungen/planung/index.html (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Badura, B. Fehlzeiten-Report 2010: Zahlen, Daten, Analysen aus allen Branchen der Wirtschaft: Vielfalt managen: Gesundheit fördern-Potenziale nutzen [Report of Absenteeism 2010: Numbers, Data, Analysis out of all Economic Sectors: Manage Diversity: Promote Health-Use Potential]; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Benedik, O.; Bönisch, M.; Gumpoldsberger, H.; Klem, S.; Martinschitz, S.; Mayerweck, E.; Pauli, W.; Peterbauer, J.; Radinger, R.; Reif, M.; et al. Bildung in Zahlen 2015/16: Schlüsselindikatoren und Analyse S. [Education in Numbers 2015/2016: Key Indicator And Analysis]; Statisik Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2017; p. 25.

- Burtscher-Mathis, S. TIES Vorarlberg/Papier 2: Bildungsverläufe und Bildungsabschlüsse im Gruppenvergleich und ihre Bedeutung im Internationalen Kontext [TIES Vorarlberg/paper2: Educational Pathways and Educational Attainment in Group Comparison and Their Importance in the Interantional Context]. 2012, pp. 40–44. Available online: www.okay-line.at/file/656/TIESVorarlber-Papier2.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- David, M.; Borde, T. Kranksein in der Fremde?: Türkische Migrantinnen im Krankenhaus [Beeing Sick in a other Country?: Türkisch Migrants in The hospital]; Mabuse-Verlag GmbH: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2001; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Domenig, D. Konzept der transkulturellen Kompetenz. [Concepts of transcultural competence]. In Transkulturelle Kompetenz: Lehrbruch für Pflege-, Gesundheits- und Sozialberufe [Transcultural Competences: Textbook for Nurses-, Health- and Social Professions]; Domenig, D., Ed.; Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 2, p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfmeister, M. Berufsethik und Berufskunde: Ein Lehrbuch für Pflegeberufe [Ethics and Nature of Profession: A Textbook for Nursing Professions]; Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG: Wien, Vienna, 2007; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, M. Defizite in der Berufsvorbereitung—Ist ein gelingender Übergang von der Schule in den Beruf? [Deficits in vocational preparation—What is a good transition between school a job?]. In Ausbildungsfähigkeit im Spannungsfeld zwischen Wissenschaft, Politik und Praxis [Trainability in the Area of Conflict between Science, Politics and Practice]; Schlemmer, E., Gerstberger, H., Eds.; VS. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; Volume 1, p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Frohner, U. Editorial Österreichische Pflegezeitschrift: Zeitschrift des Österreichischen Gesundheits- und Krankenpflegeverbandes. Austrians Nurs. Mag. Mag. Austrians Assoc. Prof. Nurs. 2017, 70, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Gläser, J.; Laudel, G. Experteninterviews und qulitative Inhaltsanalyse. [Expert Interviews and Qualitativ Content Analysis]; VS. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; Volume 4, p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Görres, S.; Bomball, J.; Schwanke, A.; Stöver, M.; Schmitt, S. "Imagekampagne für Pflegeberufe auf der Grundlage Empirisch Gesicherter Daten" Einstellungen von Schüler/innen zur Möglichen Ergreifung eines Pflegeberufes: Ergebnisbericht [Image Campaign for the Nursing Profession on the Base of Empirical Data: Attetudes of Students for a Possible Careerchoice in a Nursing Profession: Result Report]. 2010, p. 54. Available online: http://www.pflegegesellschaft-rlp.de/fileadmin/pflegesellschaft/Dokumente/Dokumente_2011/ipp_bremen_Imagekampagne_Abschlussbericht.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Habermann, M. Pflege und Kultur. Eine medizinethnologische Exploration der Pflegewissenschaft und -praxis [Nursing and culture: A medicine ethnological exploration of nursing science and practice]. In Kulturlle Dimensionen der Medizin: Ethnomedizin—Medizinethnologie—Medical Anthropology [Cultural Dimensions of Medicine: Ethnomedicine—Medical Enthnology—Medical Anthropology]; Lux, T., Ed.; Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2003; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Häfele, E. Europäisch, Jung, Mobil—Neue Zuwanderung nach Vorarlberg 2008 bis 2014 [European, Young and Mobil—New Immigration to Vorarlberg 2008 til 2014]. 2015, p. 60. Available online: https://media.arberiterkammer.at/vbg/PDF/Publikationen/neu_zuwanderung_internet_2.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, J. Stereotype als Bedrohung [Stereotyp as threat]. In Stereotype, Voruteile und soziale Diskriminierung: Theorien, Befunde und Interventionen [Steretyp, Prejudice and Social Discrimination: Therorie, Results and Intervention]; Petersen, L.-E., Six, B., Eds.; Weinheim Beltz Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; Volume 1, p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart, M. Pflegemigration nach Österreich: Eine empirische Analyse [Nursingmigration to Austria: An empirical Analysis]; Peter Lang GmbH: Frankfrut am Main, Germany, 2010; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung [Introduction into the Qulitativ Social Research]; Beltz Psychologie Verlags Union: Weinheim, Germany, 1996; Volume 3, p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken [Qualitative Content Analysis: Basis and Technique]; Beltz Verlag: Weinheim, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 12, p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- Messner, I. Geschichte der Pflege Berufsethik und Berufskunde: Ein Lehrbuch für Pflegeberufe [Nursing History: Ehtics of Profession and Nature of Profession: A Textbook for Nursing Professions]; Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG: Wien, Vienna, 2007; pp. 75–132. [Google Scholar]

- Misoch, S. Qualitative Interviews [Qualitativ Interviews]; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany; München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2019; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, Ü. Zwischen Integration und Desintegration. Positionen türkischstämmiger Jugendlicher in Deutschland [Between integration and desintegration. Postions of young people with a Turkish migration background in Germany]. In Alltag und Lebenswelten von Migrantenjugendlichen [Daily Life and Living World Form Young People with a Migration Background]; Attia, I., Marbuger, H., Eds.; IKO—Verl. für Interkulturelle Kommunikation: Frankfurt, Germany, 2000; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Schröer, H. Interkulturalität: Schlüsselbegriffe der interkulturellen Arbeit [Interculturality: Key terms in intercultural work]. In Arbeitsfeld Interkulturalität: Grundlagen, Methoden und Praxisansätze der Sozialen Arbeit in der Zuwanderungsgesellschaft [Field of Work Interculturality: Basis, Methods and Approaches of Social Work in an Immigration Society]; Kunz, T., Puhl, R., Eds.; Juventa Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Sladeĉek, E.; Marzi, L.; Schmiedbauer, T. Recht für Gesundheitsberufe: Mit allen wichtigen Berufsgesetzen [Law for Health Professions: With all Essential Professional Laws]; LexisNexis Verlag ARD Orac GmbH & Co KG: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; Volume 8, pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Spiel, C. Der Umgang mit Vielfalt im Bildungwesen 1–2 [Handling Diversity in an Educational System]. 2012, p. 1. Available online: www.oefg.at/legacy/text/stellungnahmen/Positionspapier_Vielfalt_2012.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- Sulzki, C.E. Psychologische Phasen der Migration und ihre Auswirkungen nach Carlos E Sulzki [Psychological phases of migration and their effects by Carlos E Sulzki]. In Handbuch Transkulturelle Psychiatrie [Manual of Transcultural Psychiatry]; Hegemann, T., Salman, R., Eds.; Psychiatrie-Verlag GmbH: Bonn, Germany, 2010; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Thurner, E. Der "Goldene Westen?”: Arbeitszuwanderung nach Vorarlberg seit 1945 [The "Golden West?": Labour Migratrion to Vorarlberg since 1945]; Bregenz Vorarlberger Autoren Gesellschaft: Bregenz, Austria, 1997; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli, K. Die Bevölkerung Vorarlbergs und die Staatsbürgerschaftsverleihungen im Jahr 2016 [The Population of Vorarlberg and the Awarding of Citizenship in 2016]. 2017, p. 5. Available online: https://www.vorarlberg.at/pdf/bevoelkerungundstaatsbu10.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

| Extrinsic Motivation | Group E | Group 2 | Group 3 | n = 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2 | n = 5 | n = 3 | ||

| Career possibilities | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| View of a secure job | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Potential earnings | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Thankfulness/appreciation | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Intrinsic Motivation | ||||

| Social attitude | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Ambition | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Financial independence | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keckeis, J.; Schäfer, M.; Akkaya-Kalayci, T.; Löffler-Stastka, H. Guaranteed Equal Opportunities? The Access to Nursing Training in Central Europe for People with a Turkish Migration Background. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124503

Keckeis J, Schäfer M, Akkaya-Kalayci T, Löffler-Stastka H. Guaranteed Equal Opportunities? The Access to Nursing Training in Central Europe for People with a Turkish Migration Background. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124503

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeckeis, Julia, Margit Schäfer, Türkan Akkaya-Kalayci, and Henriette Löffler-Stastka. 2020. "Guaranteed Equal Opportunities? The Access to Nursing Training in Central Europe for People with a Turkish Migration Background" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 12: 4503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124503

APA StyleKeckeis, J., Schäfer, M., Akkaya-Kalayci, T., & Löffler-Stastka, H. (2020). Guaranteed Equal Opportunities? The Access to Nursing Training in Central Europe for People with a Turkish Migration Background. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124503