How Does Mission Statement Relate to the Pursuit of Food Safety Certification by Food Companies?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

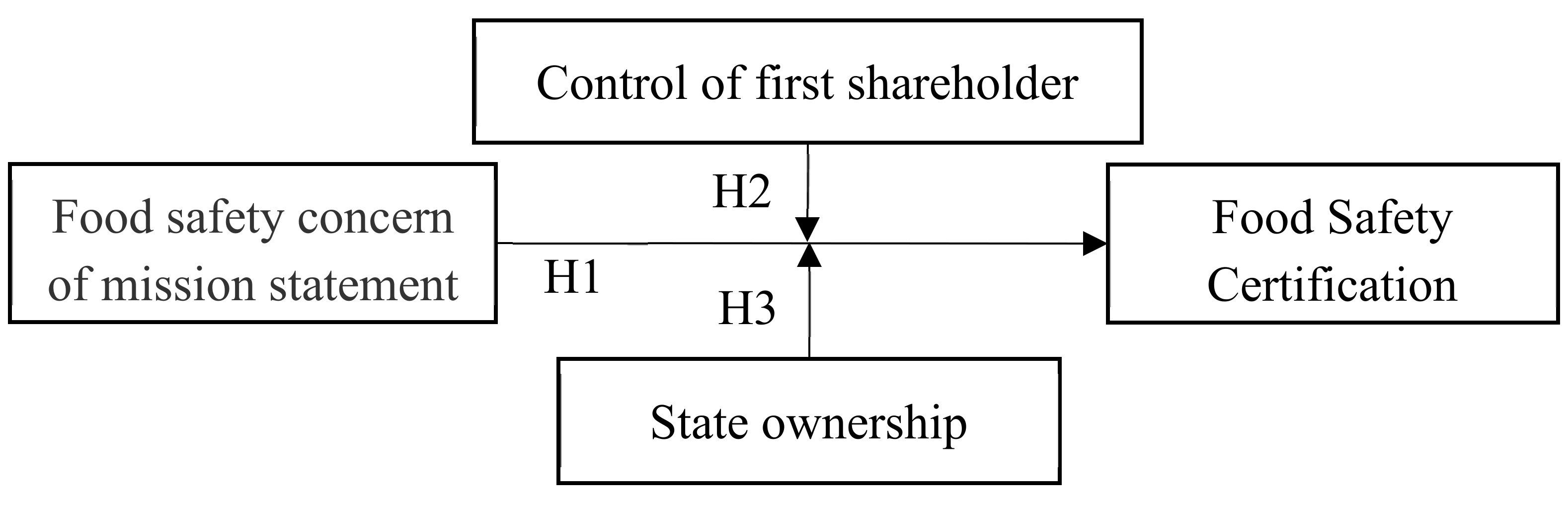

1.1. Theory and Hypothesis

1.1.1. The Relationship between Mission Statement and Food Safety Certification

1.1.2. The Moderate Effect of the Control of the Largest Shareholder

1.1.3. The Moderate Effect of the Nature of the Ownership

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.1.1. Independent Variables

2.1.2. Dependent Variables

2.1.3. Moderating Variables

2.1.4. Control Variables

2.2. Model

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T.R. Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.W.; Salin, V. An institutional approach to the examination of food safety. Int. Food Agribus. Manang. Rev. 2012, 15, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, C.W.; Jones, T.M. Stakeholder-agency theory. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, M. Towards a comparative institutional analysis: Motivations and some tentative theorizing. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 1996, 47, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Yeung, S. Creating a sense of mission. Long Range Plan. 1991, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaner, L.; Jones, P. Say It and Live It: 50 Corporate Mission Statements That Hit the Mark; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A. Corporate mission statements: The bottom line. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1987, 1, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, C.K. Product innovation charters: Mission statements for new products. R D Manag. 2002, 32, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkus, B.; Glassman, M. Do firms practice what they preach? The relationship between mission statements and stakeholder management. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R.; Houston, J.F.; Naranjo, A. Corporate socially responsible investments: CEO altruism, reputation, and shareholder interests. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y. Comparative Analysis of Mission Statements of Chinese and American Fortune 500 Companies: A Study from the Perspective of Linguistics. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartkus, B.; Glassman, M.; Mcafee, B. Mission Statement Quality and Financial Performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2006, 24, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bart, C.K. Industrial Firms and The Power of Mission. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1997, 26, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, F.R. How companies define their mission. Long Range Plan. 1989, 22, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hirc, M.A. Mission Statements: Importance, Challenge, and Recommendations for Development. Bus. Horiz. 1992, 35, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkus, B.R.; Glassman, M.; Mcafee, R.B. Mission statements: Are they smoke and mirrors? Bus. Horiz. 2000, 43, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.M.Y.; Breznik, K. What do airline mission statements reveal about value and strategy? J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 70, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, L.; Lettieri, E. Gaining legitimacy in converging industries: Evidence from the emerging market of functional food. Eur. Manag. J. 2011, 29, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czinkota, M.; Kaufmann, H.R.; Basile, G. The relationship between legitimacy, reputation, sustainability and branding for companies and their supply chains. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, J.V.; Tucker, D.J.; House, R.J. Organizational Legitimacy and the Liability of Newness. Adm. Sci. Q. 1986, 31, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, I.; Honig, B. A Process Model of Internal and External Legitimacy. Organ. Stud. 2013, 34, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, F.G.; Parsons, T. Structure and Process in Modern Societies. Adm. Sci. Q. 1961, 5, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Zaheer, S. Organizational Legitimacy Under Conditions of Complexity: The Case of the Multinational Enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, A. Mission statements. Long Range Plan. 1997, 30, 931–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.T.; Cheney, G.; Conrad, C.; Lair, D.J. Corporate Rhetoric as Organizational Discourse. In Handbook of Organizational Discourse; Grant, D., Hardy, C., Oswick, C., Philips, N., Putnam, L., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bart, C.K. High tech firms: Does mission matter? J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 1996, 7, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.A. Mission Statements Revisited. Sam Adv. Manag. J. 1996, 61, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, N. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from China. In Developments in Chinese Entrepreneurship; Cumming, D., Firth, M., Hou, W., Lee, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, S.; Pedersen, T. Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest European companies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, J. Proxy contests and the efficiency of shareholder oversight. J. Financ. Econ. 1988, 20, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Lai, K.-H. Corporate social responsibility practices and performance improvement among Chinese national state-owned enterprises. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R. A study of the R&D efficiency and productivity of Chinese firms. J. Comp. Econ. 2003, 31, 444–464. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Hu, W.; Zhu, G. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Cost of Corporate Bond: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, G.; Megginson, W.L. Does government ownership affect the cost of debt? Evidence from privatization. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2011, 24, 2693–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Potoski, M.; Prakash, A. Green clubs and voluntary governance: ISO 14001 and firms’ regulatory compliance. Am. J. Political Sci. 2005, 49, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A. Responsible care: An assessment. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Jian, W.; Zeng, Q.; Du, Y. Corporate environmental responsibility in polluting industries: Does religion matter? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.; Lin, P.; Song, F. Property rights protection and corporate R&D: Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 93, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalache, O.R.; Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Offshoring and firm innovation: The moderating role of top management team attributes. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1480–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-L.; Kung, F.-H. Drivers of environmental disclosure and stakeholder expectation: Evidence from Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, K.; Zhang, R. Do lenders value corporate social responsibility? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.E.; Bansal, P. Consumers’ willingness to pay for corporate reputation: The context of airline companies. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F.; Richter, A.W. Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, I. Realizing the power of strategic vision. Long Range Plan. 1992, 25, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, M.; Sanderson, S.; Luffman, G. Mission statements: Selling corporate values to employees. Long Range Plan. 1991, 24, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.S. The mission statement: A corporate reporting tool with a past, present, and future. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2008, 45, 94–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, M.B.; Wharton, A.S.; Goodstein, J. Exploring the relationship between mission statements and work-Life practices in organizations. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 427–450. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Food safety certification | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.63 | 0.48 | - | ||

| 2. Food safety concern of mission statement | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 ** | - | |

| 3. SOE (d) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.13 ** | −0.06 | - |

| 4. First | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.10 ** | 0.00 | 0.15 ** |

| 5. Size | 19.24 | 25.80 | 21.96 | 1.06 | 0.18 ** | −0.01 | 0.15 ** |

| 6. CEO (d) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.26 | 0.44 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.26 ** |

| 7. Board | 0.14 | 0.80 | 0.38 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 8. Financial leverage | 0.02 | 1.51 | 0.37 | 0.19 | −0.10 ** | 0.03 | 0.08 * |

| 9. Capin | 0.18 | 357.29 | 2.52 | 12.75 | −0.07 * | −0.01 | −0.05 |

| 10. Age | 0.00 | 3.50 | 2.78 | 0.33 | 0.06 | −0.08 * | 0.12 ** |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 3. SOE | - | ||||||

| 4. First | 0.15 ** | - | |||||

| 5. Size | 0.15 ** | 0.16 ** | - | ||||

| 6. CEO (d) | −0.26 ** | 0.01 | −0.05 | - | |||

| 7. Board | 0.04 | 0.08 * | 0.11 ** | 0.00 | - | ||

| 8. Lev | 0.08 * | −0.07 * | 0.20 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.03 | - | |

| 9. Capin | −0.05 | −0.07 * | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.07 * | - |

| 10. Age | 0.12 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.00 |

| Dependent Variable | Food Safety Certification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Size | 0.355 *** (0.080) | 0.318 *** (0.084) | 0.370 *** (0.087) | 0.263 *** (0.085) | 0.335 *** (0.089) |

| CEO | −0.269 (0.171) | −0.113 (0.178) | −0.025 (0.182) | −0.125 (0.180) | 0.013 (0.186) |

| Board | −1.757 (1.116) | −2.169 * (1.155) | −2.509 ** (1.174) | −2.747 ** (1.210) | −3.104 ** (1.235) |

| Financial leverage | −1.208 *** (0.431) | −1.269 *** (0.445) | −1.196 *** (0.449) | −1.467 *** (0.455) | −1.460 *** (0.460) |

| Capin | −0.042 * (0.022) | −0.033 (0.021) | −0.034 (0.022) | −0.033 (0.021) | −0.034 (0.022) |

| Age | −0.334 (0.252) | −0.407 (0.264) | −0.339 (0.263) | −0.313 (0.262) | −0.217 (0.261) |

| Year | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| First | 0.626 (0.543) | 0.827 (0.554) | 1.095 ** (0.557) | 1.435 ** (0.576) | |

| SOE | 0.669 *** (0.166) | 0.743 *** (0.170) | 0.852 *** (0.182) | 0.960 *** (0.185) | |

| Food safety concern of mission statement | 3.045 ** (1.257) | 3.627 *** (1.390) | 6.537 *** (1.336) | 6.147 *** (1.365) | |

| Food safety concern of mission statement X First | 0.411 *** (0.129) | 0.479 *** (0.126) | |||

| Food safety concern of mission statement X SOE | 0.637 *** (0.127) | 0.720 *** (0.130) | |||

| Constant | −4.485 ** (1.895) | −3.988 ** (1.954) | −5.410 *** (2.038) | −3.136 (1.986) | −5.045 ** (2.083) |

| Estimation model | Logistic | Logistic | Logistic | Logistic | Logistic |

| Number of observations | 872 | 872 | 872 | 872 | 872 |

| Log Likelihood | −532.219 | −518.815 | −513.562 | −504.247 | −496.708 |

| Dependent Variable | High Shareholder Control | Low Shareholder Control |

|---|---|---|

| Food Safety Certification | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Size | 0.505 *** (0.137) | 0.246 ** (0.111) |

| CEO | 0.379 (0.261) | −0.539 * (0.278) |

| Board | −2.868 * (1.584) | −3.097 * (1.868) |

| Financial leverage | −1.466 ** (0.643) | −1.399 ** (0.649) |

| Capin | −0.218 * (0.116) | −0.034 (0.022) |

| Age | 0.353 (0.321) | −1.787 *** (0.519) |

| Year | Included | Included |

| SOE | 0.710 *** (0.257) | 0.614 ** (0.243) |

| Food safety concern of mission statement | 7.336 *** (2.181) | 1.986 (1.889) |

| Constant | −9.912 *** (3.102) | 2.535 (2.843) |

| Estimation model | Logistic | Logistic |

| Number of observations | 439 | 433 |

| Log Likelihood | −246.270 | −256.799 |

| Dependent Variable | SOE = 1 | SOE = 0 |

|---|---|---|

| Food Safety Certification | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Size | 0.476 *** (0.145) | 0.088 (0.116) |

| CEO | 1.195 ** (0.497) | −0.461 ** (0.211) |

| Board | −2.531 (1.793) | −2.331 (1.790) |

| Financial leverage | −2.840 *** (0.841) | −0.789 (0.581) |

| Capin | 0.380 ** (0.166) | −0.048 * (0.027) |

| Age | 0.039 (0.555) | −0.269 (0.320) |

| Year | Included | Included |

| First | 0.911 (1.191) | 1.458 ** (0.682) |

| Food safety concern of mission statement | 16.693 *** (3.232) | −0.264 (1.003) |

| Constant | −9.665 *** (3.684) | 0.977 (2.752) |

| Estimation model | Logistic | Logistic |

| Number of observations | 377 | 495 |

| Log Likelihood | −183.535 | −303.818 |

| Dependent Variable | Food Safety Certification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Size | 0.061 *** (0.016) | 0.067 *** (0.016) | 0.055 *** (0.016) | 0.062 *** (0.016) |

| CEO | −0.017 (0.037) | −0.001 (0.038) | −0.021 (0.037) | 0.001 (0.037) |

| Board | −0.467 * (0.238) | −0.504 ** (0.238) | −0.586 ** (0.236) | −0.655 *** (0.235) |

| Lev | 0.231 *** (0.089) | −0.218 ** (0.089) | −0.270 *** (0.088) | −0.255 *** (0.088) |

| Capin | −0.002 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.001) | −0.002 (0.001) |

| Age | −0.086 (0.054) | −0.073 (0.054) | −0.064 (0.054) | −0.043 (0.054) |

| Year | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| First | 0.144 (0.112) | 0.157 (0.112) | 0.231 ** (0.112) | 0.262 ** (0.112) |

| SOE | 0.141 *** (0.034) | 0.150 *** (0.034) | 0.149 *** (0.034) | 0.163 *** (0.034) |

| Food safety concern of mission statement | 0.456 ** (0.186) | 0.313 (0.195) | 1.078 *** (0.220) | 0.948 *** 0.222) |

| Food safety concern of mission statement X First | 0.055 ** (0.024) | 0.080 *** (0.024) | ||

| Food safety concern of mission statement X SOE | 0.104 *** (0.020) | 0.117 *** (0.020) | ||

| Estimation model | OLS | OLS | OLS | OLS |

| Number of observations | 872 | 872 | 872 | 872 |

| R2 | 0.067 | 0.073 | 0.095 | 0.107 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y. How Does Mission Statement Relate to the Pursuit of Food Safety Certification by Food Companies? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134735

Lin Q, Zhu Y, Zhang Y. How Does Mission Statement Relate to the Pursuit of Food Safety Certification by Food Companies? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(13):4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134735

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Quan, Yutao Zhu, and Yue Zhang. 2020. "How Does Mission Statement Relate to the Pursuit of Food Safety Certification by Food Companies?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 13: 4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134735