Efficacy of a Six-Week Dispersed Wingate-Cycle Training Protocol on Peak Aerobic Power, Leg Strength, Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Lipids and Quality of Life in Healthy Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Pre- and Post-Experimental Procedures

2.3. Peak Oxygen Uptake

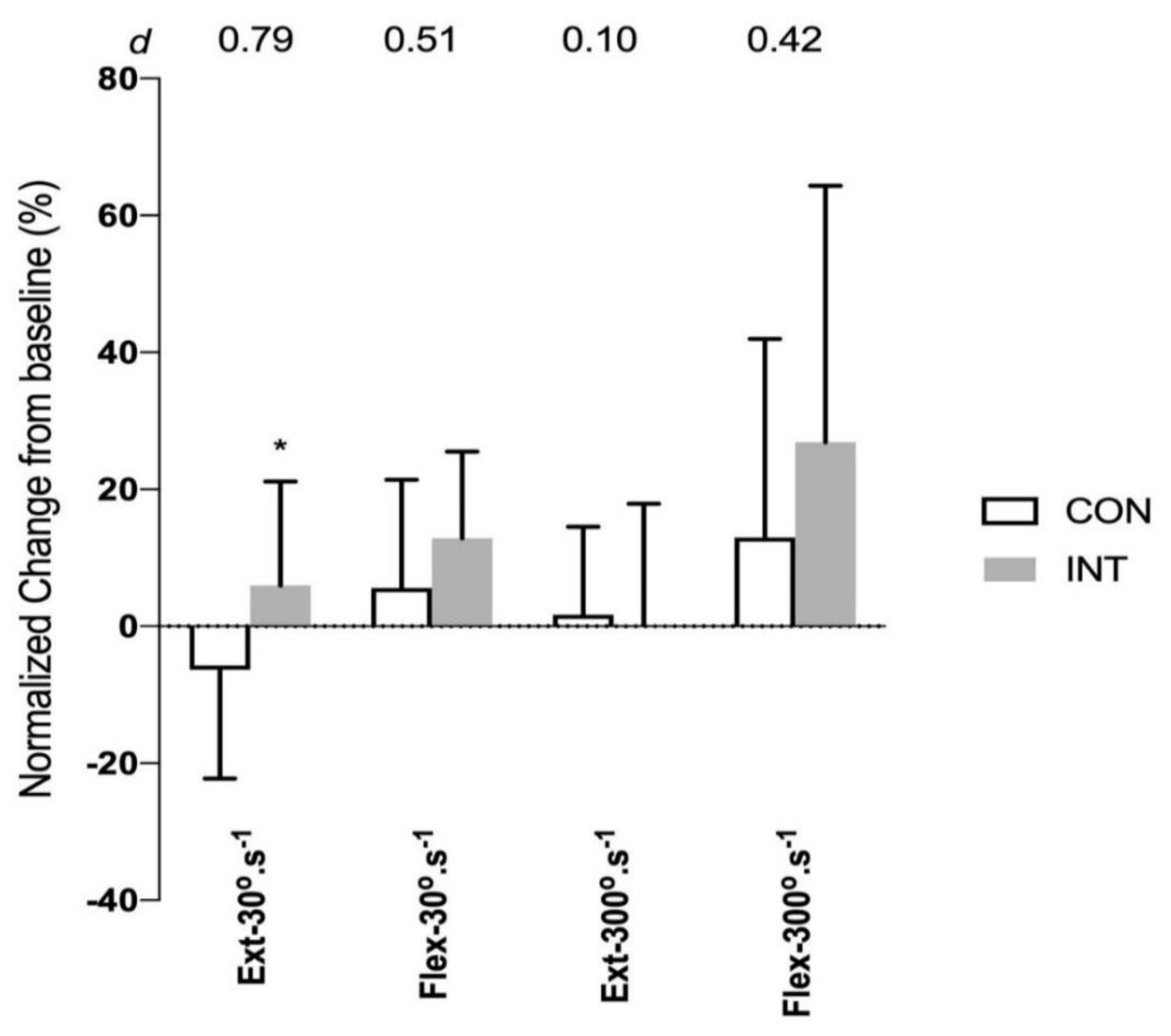

2.4. Leg Strength

2.5. Lipid Profile

2.6. Insulin Resistance Markers

2.7. Psychological Measures

2.8. Exercise Training Intervention

3. Statistical Analysis

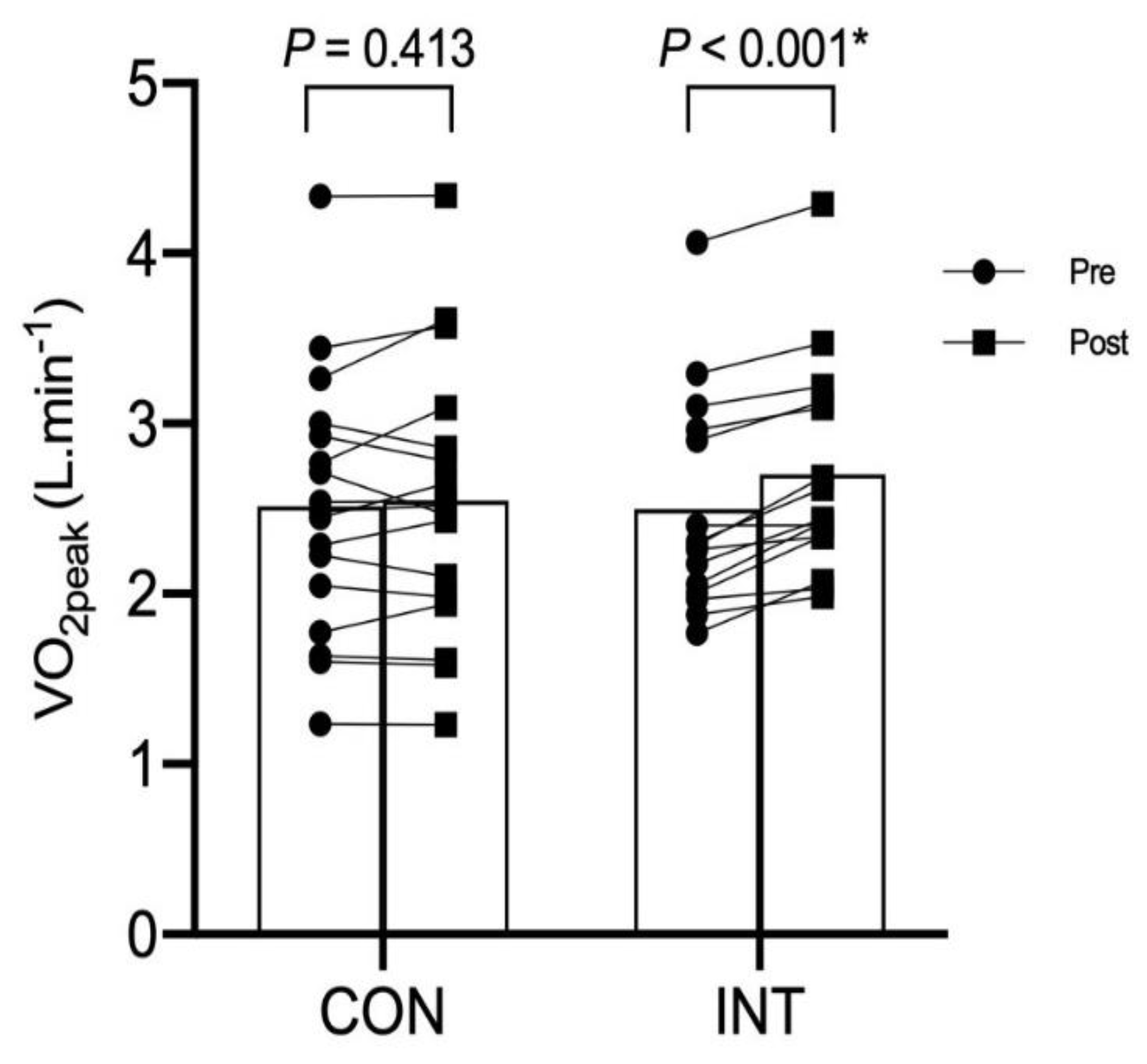

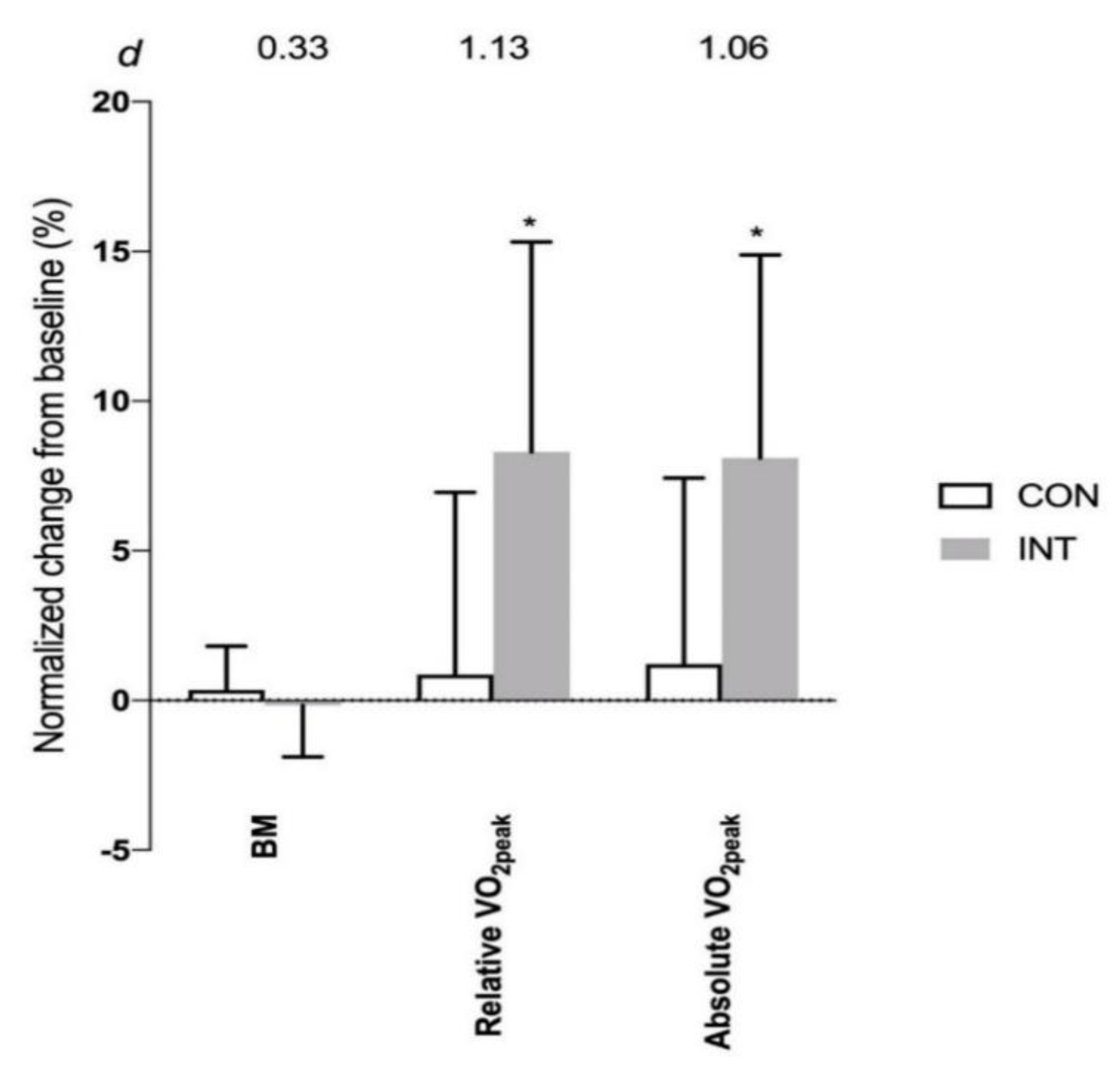

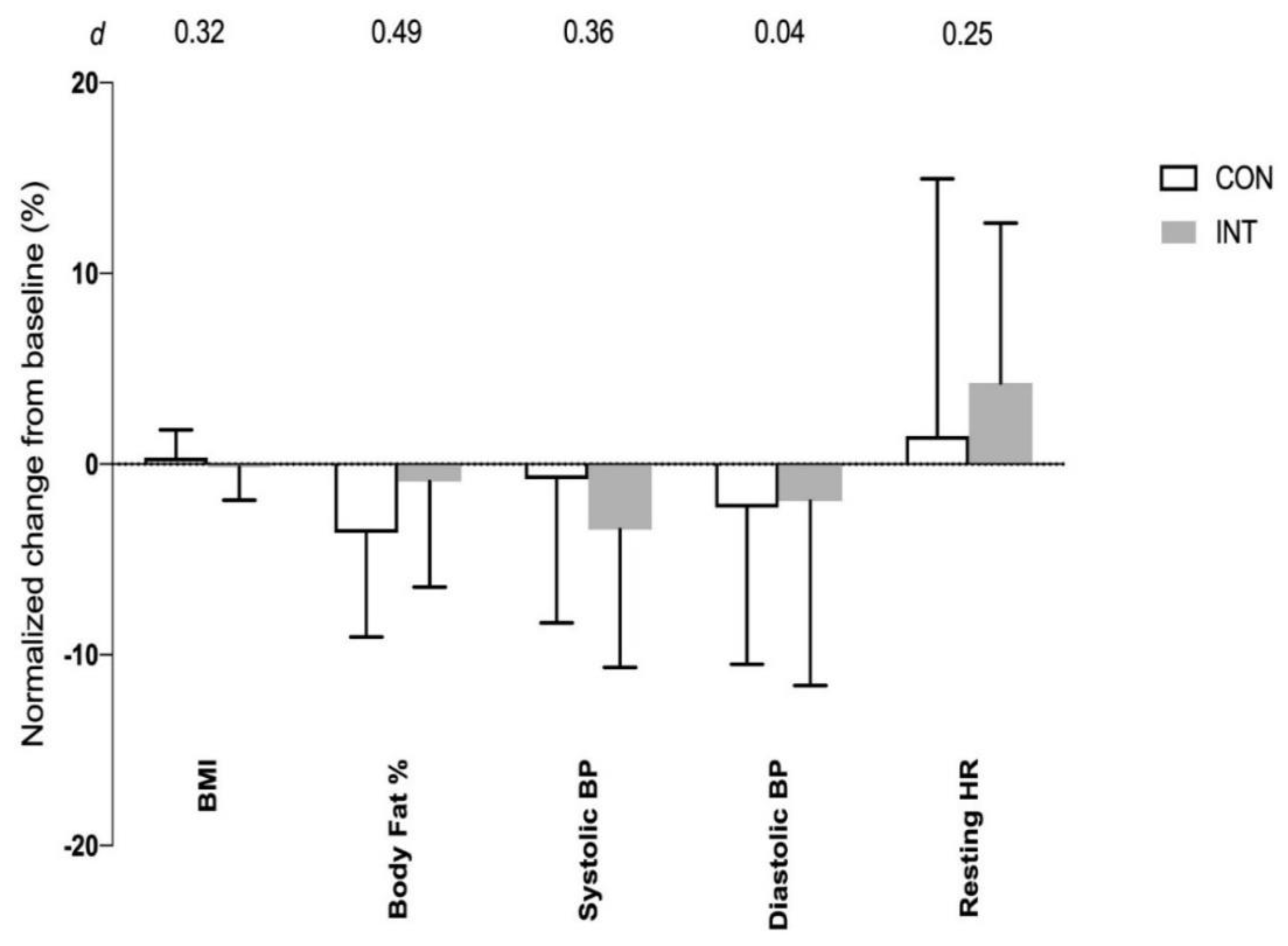

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fastats: Exercise or Physical Activity. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/exercise.htm (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/ (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- Chua, L.; Soh, I.; Health Status and Health Related Behaviors in Adults with Self-Reported Diabetes. Statistics Singapore Newsletter. 2016. Available online: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/society/ssnsep16-pg5-9.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2019).

- Roth, M. Self-reported physical activity in adults. In Health Survey for England; Craig, R., Mindell, J., Hirani, V., Eds.; National Centre for Social Research: London, UK, 2008; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gibala, M.J.; Little, J.P.; Essen, M.V.; Wilkin, G.P.; Burgomaster, K.A.; Safdar, A.; Raha, S.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Short-term sprint interval versus traditional endurance training: Similar initial adaptations in human skeletal muscle and exercise performance. J. Physiol. 2006, 575, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibala, M.J.; Little, J.P.; MacDonald, M.J.; Hawley, J.A. Physiological adaptations to low volume high intensity interval training in health and disease. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, N.H.; Fedewa, M.V.; Dishman, R.K.; Cureton, K.J. Sprint interval training effects on aerobic capacity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibala, M.J.; McGee, S.L. Metabolic adaptations to short term high intensity interval training. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2008, 36, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Puigserver, P.; Andersson, U.; Zhang, C.; Adelmant, C.; Mootha, V.; Troy, C.; Cinti, S.; Lowell, B.; Scarpulla, R.C.; et al. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 1999, 98, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egan, B.; Carson, B.P.; Garcia-Roves, P.M.; Chibalin, A.V.; Sarsfield, F.M.; Barron, N.; McCaffrey, N.; Moyna, N.M.; Zierath, J.R.; O’Gorman, D.J. Exercise intensity-dependent regulation of PGC-1a mRNA abundance is associated with differential activation of upstream signalling kinases in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 1779–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrbom, J.; Sundberg, C.J.; Ameln, H.; Kraus, W.E.; Jansson, E.; Gustafsson, T. PGC-1a mRNA expression is influenced by metabolic perturbation in exercising human skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 96, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Hughes, S.C.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Bradwell, S.N.; Gibala, M.J. Six sessions of sprint interval training increases muscle oxidative potential and cycle endurance capacity in human. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 1985–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Heigenhauser, G.J.; Gibala, M.J. Effect of short-term sprint interval training on human skeletal muscle carbohydrate metabolism during exercise and time-trial performance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 2041–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, J.B.; Percival, M.E.; Skelly, L.E.; Martin, B.J.; Tan, R.B.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Gibala, M.J. Three minutes of all-out intermittent exercise per week increases skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and improves cardiometabolic health. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herazo-Beltrán, Y.; Pinillos, Y.; Vidarte, J.; Crissien, E.; Suarez, D.; Garcia, R. Predictors of perceived barriers to physical activity in the general adult population: A cross-sectional study. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2017, 21, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollaard, N.B.; Metcalfe, R.; Williams, S. Effect of number of sprints in a SIT session on change in VO2max: A meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitranun, W.; Deerochanawong, C.; Tanaka, H.; Suksom, D. Continuous vs interval training on glycemic control and macro-and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, B.H.; Lim, I.; Tian, R.; Tan, F.; Aziz, A.R. Effects of novel exercise training protocol of Wingate-based sprint bouts dispersed over a day on selected cardiometabolic health markers in sedentary females: A pilot study. BMJ. Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.P.; Langley, J.; Lee, M.; Myette-Côté, E.; Jackson, G.; Durrer, C.; Gibala, M.J.; Jung, M.E. Sprint exercise snacks: A novel approach to increase aerobic fitness. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and b cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentration in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaz, A.; Nambi, S.S.; Mather, K.; Baron, A.D.; Follmann, D.A.; Sulivan, G.; Quon, M.J. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: A simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 2402–2410. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, A.M.; Herbert, P.; Easton, C.; Sculthorpe, N.; Grace, F.M. Impact of low volume, high intensity interval training on maximal aerobic capacity, health-related quality of life and motivation to exercise in ageing man. Aging 2015, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campolina, A.G.; Ciconelli, R.M. SF 36 and the development of new assessment tools for quality of life. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2008, 33, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, G. Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, P.B.; Jenkins, D.G. The scientific basis for high-intensity interval training: Optimizing training programmes and maximizing performance in highly trained endurance athletes. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, N.; Spriet, L.L.; Heigenhauser, G.J.F.; Kowalchuk, J.M.; Sutton, R.; Jones, N.L. Muscle power and metabolism in maximal intermittent exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986, 60, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacInnis, M.J.; Skelly, L.E.; Gibala, M.J. CrossTalk proposal: Exercise training intensity is more important than volume to promote increases in human skeletal muscle mitochondrial content. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 4111–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astorino, T.A.; Allen, R.P.; Roberson, D.W.; Jurancich, M. Effect of high intensity interval training on cardiovascular function, VO2max and muscular force. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, L.; Al-Shanti, N.; Bradburn, S.; Baig, O.; Slevin, M.; McPhee, J.S. Sex comparison of knee extensor size, strength and fatigue adaptation to sprint interval training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellyman, C.; Yates, T.; O’Donovan, G.; Gray, L.J.; King, J.A.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. The effects of high intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 942–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Little, J.P.; Gillen, J.B.; Percival, M.E.; Safdar, A.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Punthakee, Z.; June, M.E.; Gibala, M.J. Low volume high intensity interval training reduces hyperglycaemia and increases muscle mitochondrial capacity in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartman, Y.A.; Hopman, M.T.; Schreuder, T.H.; Verheggen, R.J.; Scholten, R.R.; Oudegeest-Sander, M.H.; Poelkens, F.; Maiorana, A.J.; Naylor, L.H.; Willems, P.H.; et al. Improvements in fitness are not obligatory for exercise training-induced improvements in CV risk factors. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons, J.A.; Knudsen, S.; Rankinen, T.; Koch, L.G.; Sarzynski, M.; Jensen, T.; Keller, P.; Scheele, C.; Vollaard, N.B.; Nielsen, S.; et al. Using molecular classification to predict gains in maximal aerobic capacity following endurance exercise training in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 108, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Buchan, D.S.; Ollis, S.; Young, J.D.; Cooper, S.M.; Shield, J.P.; Baker, J.S. High intensity interval running enhances measures of physical fitness but not metabolic measures of cardiovascular disease risk in healthy adolescents. BMC Public Health 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanley, A.J.G.; Williams, K.; Stern, M.P.; Haffner, S.M. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance in relation to the incidence of cardiovascular disease: The San Antonio heart study. Diabetes Care. 2002, 25, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonora, E.; Formentini, G.; Calcaterra, F.; Lombardi, S.; Marini, F.; Zenari, L.; Saggiani, F.; Poli, M.; Perbellini, S.; Raffaelli, A.; et al. HOMA-estimated insulin resistance is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetic subjects- prospective data from the Verona Diabetes Complicated Study. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fox, E.L.; Bartels, R.L.; Billings, C.E.; Mathews, D.K.; Bason, R.; Webb, W.M. Intensity and distance of interval training programs and changes in aerobic power. Med. Sci. Sports 1973, 5, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Little, J.P.; Safdar, A.; Wilkin, G.P.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Gibala, M.J. A practical model of low-volume high-intensity interval training induces mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle: Potential mechanisms. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babraj, J.A.; Vollard, N.B.; Keast, C.; Guppy, F.M.; Cottrell, G.; Timmons, J.A. Extremely short duration high intensity interval training substantially improves insulin action in young healthy males. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Withers, R.T.; Sherman, W.M.; Clark, D.G.; Esselbach, P.C.; Nolan, S.R.; Mackay, M.H.; Brinkman, M. Muscle metabolism during 30, 60 and 90s of maximal cycling on an air-braked ergometer. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991, 63, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyfault, J.P. Setting the stage: Possible mechanism by which acute contraction restores insulin sensitivity in muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 294, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mann, S.; Beedie, C.; Jimenez, A. Differential effects of aerobic exercise, resistance training and combined exercise modalities on cholesterol and the lipid profile: Review, synthesis and recommendations. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koubaa, A.; Trabelsi, H.; Masmoudi, L.; Elloumi, M.; Sahnoun, Z.; Zeghal, K.M.; Hakim, A. The effects of intermittent and continuous training on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness and lipid profile in obese adolescents. J Pharm. 2013, 3, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racil, G.; Ben Ounis, O.; Hammouda, O.; Kallel, A.; Zouhal, H.; Chamari, K.; Amri, M. Effects of high vs. moderate exercise intensity during interval training on lipids and adiponectin levels in obese young females. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racil, G.; Coquart, J.B.; Elmontassar, W.; Haddad, M.; Goebel, R.; Chaouachi, A.; Amri, M.; Chamari, K. Greater effects of high- compared with moderate-intensity interval training on cardio-metabolic variables, blood leptin concentration and ratings of perceived exertion in obese adolescent females. Biol. Sport. 2016, 33, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouse, S.F.; O’Brien, B.C.; Grandjean, P.W.; Lowe, R.C.; Rohack, J.J.; Green, J.S.; Tolson, H. Training intensity, blood lipids and apolipoproteins in men with high cholesterol. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 82, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nybo, L.; Sundstrup, E.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Mohr, M.; Hornstrup, T.; Simonsen, L.; Bülow, J.; Randers, M.B.; Nielsen, J.J.; Aagaard, P.; et al. High intensity training versus traditional exercise interventions for promoting health. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1951–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ouergil, N.; Fradj, M.K.; Bezrati, I.; Khammassi, M.; Feki, M.; Kaabachi, N.; Bouassida, A. Effects of high intensity interval training on body composition, aerobic and anaerobic performance in plasma lipids in overweight/obese and normal weight young men. Biol. Sport 2017, 34, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Verney, J.; Duclos, M.; Thivel, D. Sprint interval training: What are the clinical implications and precautions? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 2361–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akins, J.D.; Crawford, C.K.; Burton, H.M.; Wolfe, A.S.; Vardarli, E.; Coyle, E.F. Inactivity induces resistance to the metabolic benefits following acute exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masharani, U.; Goldfine, I.D.; Youngren, J.F. Influence of gender on the relationship between insulin sensitivity, adiposity and plasma lipids in lean non-diabetic subjects. Metabolism 2009, 58, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Exercise Component Variables | Clustered WAnT Bouts Protocol | Dispersed WAnT Bouts Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Warm-up duration | 1 × 60-s = 1.0 min | 3 × 60-s = 3.0 min |

| Bouts duration | 3 × 30-s = 1.5 min | 3 × 30-s = 1.5 min |

| Recovery duration between bouts | 2 × 4 min = 8 min | ~4 h (but this duration is part of individual’s official work time and is hence excluded from the exercise time) |

| Total exercise time per day or per session | 10.5 min | 4.5 min |

| Total exercise time per week (based on 3 training days per week) | 31.5 min | 13.5 min (~60% less time commitment vs. clustered protocol) |

| Duration of the Rest Periods | Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|

| Between 0–1 h | 0 |

| Between 1–2 h | 0.88 |

| Between 2–3 h | 17.61 |

| Between 3–4 h | 31.16 |

| Between 4–4.5 h | 50.35 |

| Measured Variables | CON Group (N = 17; 8 M + 9 F) | INT Group (N =16; 8 M + 9 F) | p Value between Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 35.1 ± 6.9 | 34.1 ± 6.3 | 0.68 |

| Stature (cm) | 167 ± 8 | 168 ± 11 | 0.82 |

| Body mass (kg) | 69.0 ± 14.7 | 69.3 ± 14.2 | 0.86 |

| Body fat (%) | 26.3 ± 9.8 | 24.9 ± 7.2 | 0.63 |

| Resting Systolic BP (mmHg) | 120 ± 14 | 117 ± 13 | 0.53 |

| Resting Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79 ± 11 | 76 ± 8 | 0.33 |

| Resting HR (b·min−1) | 65 ± 10 | 63 ± 10 | 0.84 |

| VO2peak (L·min−1) | 2.50 ± 0.68 | 2.58 ± 0.86 | 0.75 |

| VO2peak (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 36.9 ± 9.6 | 36.7 ± 6.7 | 0.97 |

| MVC flexion 30°·s−1 (Nm) | 158 ± 42 | 168 ± 59 | 0.59 |

| MVC extension 30°·s−1 (Nm) | 91 ± 31 | 86 ± 25 | 0.66 |

| MVC flexion 300°·s−1 (Nm) | 80 ± 27 | 87 ± 31 | 0.46 |

| MVC extension 300°·s−1 (Nm) | 55 ± 23 | 48 ± 16 | 0.36 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol·L−1) | 4.97 ± 0.75 | 4.74 ± 0.93 | 0.45 |

| Triglycerides (mmol·L−1) | 2.00 ± 1.06 | 1.79 ± 0.99 | 0.56 |

| HDL (mmol·L−1) | 1.68 ± 0.46 | 1.60 ± 0.37 | 0.58 |

| LDL (mmol·L−1) | 2.87 ± 0.71 | 2.77 ± 0.75 | 0.71 |

| Fasting Glucose (mmol·L−1) | 4.79 ± 0.57 | 4.56 ± 0.42 | 0.21 |

| Fasting Insulin (mmol·L−1) | 5.96 ± 3.70 | 4.68 ± 3.16 | 0.29 |

| Insulin resistance–HOMA (au) | 1.32 ± 0.89 | 0.96 ± 0.71 | 0.22 |

| Insulin sensitivity–QUICKI (au) | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 0.99 |

| WAnT Bouts of the Day | Peak Power (W) | Mean Power (W) |

|---|---|---|

| Morning Bout | 838 ± 312 | 555 ± 189 |

| Afternoon Bout | 839 ± 318 | 552 ± 191 |

| Evening Bout | 850 ± 317 | 555 ± 194 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wun, C.H.; Zhang, M.J.; Ho, B.H.; McGeough, K.; Tan, F.; Aziz, A.R. Efficacy of a Six-Week Dispersed Wingate-Cycle Training Protocol on Peak Aerobic Power, Leg Strength, Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Lipids and Quality of Life in Healthy Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134860

Wun CH, Zhang MJ, Ho BH, McGeough K, Tan F, Aziz AR. Efficacy of a Six-Week Dispersed Wingate-Cycle Training Protocol on Peak Aerobic Power, Leg Strength, Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Lipids and Quality of Life in Healthy Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(13):4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134860

Chicago/Turabian StyleWun, Chun Hou, Mandy Jiajia Zhang, Boon Hor Ho, Kenneth McGeough, Frankie Tan, and Abdul Rashid Aziz. 2020. "Efficacy of a Six-Week Dispersed Wingate-Cycle Training Protocol on Peak Aerobic Power, Leg Strength, Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Lipids and Quality of Life in Healthy Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 13: 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134860

APA StyleWun, C. H., Zhang, M. J., Ho, B. H., McGeough, K., Tan, F., & Aziz, A. R. (2020). Efficacy of a Six-Week Dispersed Wingate-Cycle Training Protocol on Peak Aerobic Power, Leg Strength, Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Lipids and Quality of Life in Healthy Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134860