Employment Legal Framework for Persons with Disabilities in China: Effectiveness and Reasons

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Theoretical Underpinning of the Disability Employment Legislation

2.1. Explaining Disability in the International Context

2.2. Understanding Disability in the Chinese Context

A disabled person is referred to as those who suffer from abnormalities of loss of a certain organ or function, psychologically or physiologically, or in anatomical structure and has lost wholly or in part the ability to perform an activity in the normal way.[26]

2.3. Two Disability Employment Legislative Approaches

3. Poor Outcomes of the Anti-Discrimination Legal Framework

3.1. The Anti-Discrimination Legal Framework

No discrimination against persons with disabilities shall be practiced in the employment, promotion, determination of technical and professional titles, remunerations, welfare, rest and vacation, social insurances, etc.[34]

3.2. Reasons for Poor Outcomes of the Anti-Discrimination Legal Framework

While commending the legal prohibition of disability-based discrimination in the state party, the Committee is concerned about the lack of a comprehensive definition of discrimination against persons with disabilities.[33]

(i) Where any of the legal rights and interests of a person with disabilities is violated, he or she may file a complaint with the disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs). The DPOs shall protect legal rights and interests of him or her and have the right to require a relevant department or entity to investigate and deal with the case. These entities shall legally do it and make a reply.

(ii) Where a person with disabilities needs help in the protection of his legal rights and interests through litigation, the DPOs shall give support to him or her.

(iii) The DPOs shall have the right to require the relevant departments to legally investigate and deal with any violations of the interests of specific group of persons with disabilities.[35]

If the legal rights and interests of a person with disabilities is violated, he or she shall have rights to require the relevant departments to deal with it, or apply to the arbitrate institution for arbitration, or litigate according to law.[35]

4. The Weak Impact of the Employment Quota Scheme Legal Framework

4.1. The Evolutionary Process of China’s Employment Quota Scheme Legal Framework

A state organ, social group, enterprise, public institution or private non-enterprise entity shall arrange employment of persons with disabilities in a prescribed proportion and choose proper types of work and posts for them. If the prescribed proportion was not reached, it shall fulfill the obligation to ensure the employment of the disabled under the relevant provisions of the state. The state shall encourage the entity employers to arrange employment of persons with disabilities in excess of the prescribed proportion.[26]

Payable amount = (number of total employees in the previous year × employment quotas required by the local government—number of employees with disabilities) × local average annual social wage in the previous year.[47]

Payable amount = (number of total employees in the previous year × employment quotas required by the local government − number of employees with disabilities) × average annual wage of the employees in the previous year.

4.2. Reasons that the Quota Scheme Legal Framework Is Not Well-Functioning

4.2.1. Legal Framework of the Mainstream Labor Market

4.2.2. Protection Effects of the Mainstream Labor Market Legal Framework

4.2.3. Conflicting Provisions between the General and Special Legal Frameworks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO); World Bank. The World Report on Disability; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 7. Available online: File:///C:/Users/dell/Downloads/9789240685215_eng%20 (1).pdf (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Cheng, K. Uphold the targeted poverty alleviation strategy, focus on addressing the poverty caused by disease. Adm. Reform 2018, 7, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Buckup, S. The Price of Exclusion: The Economic Consequences of Excluding People with Disabilities from the World of Work; International Labor Organization Employment Working Paper No. 43; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF). The Disability Cause Development Statistical Communiqué in 2019; CDPF: Beijing, China, 2019; Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/sjzx/tjgb/202004/t20200402_674393.shtml (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Lai, D.S.; Liao, J.; Liu, W. Analysis of the employment and its influencing factors of persons with disabilities in China. J. Renmin Univ. China 2008, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X.J.; Zhao, M.M. Analysis of the economic growth effects on employment of persons with disabilities. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2012, 4, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.Q. Exchanging, welfare or disincentive—Protective employment of persons with disabilities. Sociol. Stud. 2014, 1, 148–173. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Marks, L.A.B. Law and the social construction of disability. In Disability, Diversity and Legal Change; Jones, M., Marks, L.A.B., Eds.; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, A.S. The law: What’s disability studies got to do with it or an introduction to disability legal studies. Columbia Hum. Rights Law Rev. 2011, 42, 403–479. [Google Scholar]

- Liachowitz, C.H. Disability as a Social Construct: Legislative Roots; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1988; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Humpage, L. Models of disability, work and welfare in Australia. Soc. Policy Adm. 2007, 41, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linker, B. On the borderland of medical and disability history: A survey of the fields. Bull. Hist. Med. 2013, 87, 499–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, T.; Pritchard, G.W. Being fat: A conceptual analysis using three models of disability. Disabil. Soc. 2011, 26, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bury, M.R.; Wood, P.H.N. Sociological perspectives in research on disablement. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 1, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps: A Manual of Classification Related to the Consequence of Disease; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1980; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M.J. The Politics of Disablement; Macmillan: London, UK, 1990; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, L. Including all of our lives: Renewing the social model of disability. In Exploring the Divide: Illness and Disability; Barnes, C., Mercer, G., Eds.; The Disability Press: Leeds, UK, 1996; pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, H. Towards a politics of disability: Definitions, disciplines, and policies. Soc. Sci. J. 1985, 22, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Degener, T. A new human rights model of disability. In The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons; Fina, V.D., Cera, R., Palmisano, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Degener, T.; Quinn, G. A survey of international, comparative and regional disability law reform. In Disability Rights Law and Policy: International and National Perspectives; Yee, S., Breslin, M.L., Eds.; Transnational: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–128. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, T.; Watson, N. The social model of disability: An outdated ideology? In Exploring Theories and Expanding Methodologies: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go (Research in Social Science & Disability):2(Research in Social Science and Disability); Barnartt, S.N., Atlman, B.M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK; West Yorkshire, UK, 2001; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD); UN: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.R. Connotations and implications of people’s livelihood. J. Xiamen Univ. (Arts Soc. Sci.) 2019, 4, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.Y. Disability History in China; Xuelin Publisher: Shanghai, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities (Order No.36[1990] of the President); Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress: Beijing, China, 1990; Article 2. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2008-04/24/content_953439.htm (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF). Notice of the China Disabled Persons’ Federation on the Unified Issue of the “China Disability Certification Card” (CDPF, No.61 [1995]); CDPF: Beijing, China, 1995; Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/zcwj/zxwj/200804/t20080408_38100.shtml (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Harris, S.P.; Owen, R.; Gould, R. Parity of participation in liberal welfare states: Human rights, neoliberalism, disability and employment. Disabil. Soc. 2012, 27, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böheim, R.; Leoni, T. Sickness and disability policies: Reform paths in OECD countries between 1990 and 2014. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2018, 27, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.; Lunt, N. Disability and employment: Toward an understanding of discourse and policy. Disabil. Soc. 1994, 9, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, L. A European right to employment for disabled people. In Human Rights and Disabled Persons: Essays and Relevant Human Rights Instruments; Degener, T., Koster-Dreese, Y., Eds.; Martinus Nijhoff: London, UK, 1995; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Diller, M. Dissonant disability policies: The tensions between the Americans with Disabilities Act and federal disability benefit programs. Tex. Law Rev. 1998, 76, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of China (no.41); Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/countries/CHN (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Law of the PRC on the Protection of Persons with disabilities (2008 Amendment) (Order No.3 [2008] of the President); Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress: Beijing, China, 2008. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2008-04/24/content_953439.htm (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- State Council. Regulation of the PRC on the Employment of Persons with Disabilities (Order No.488 [2007] of the State Council); State Council: Beijing, China, 2007. Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/zcwj1/flfg/200711/t20071114_25286.shtml (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Degener, T. The definition of disability in German and Foreign Discrimination Law. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2006, 26. Available online: https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/696/873 (accessed on 10 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Degener, T. Disability discrimination law: A global comparative approach. In Disability Rights in Europe: From Theory to Practice; Lawson, A., Gooding, C., Eds.; Hart: Oxford, OR, USA; Portland, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, B.M. Disability definitions, models, classification schemes and applications. In Handbook of Disability Studies; Albrechat, G.L., Seelman, K.D., Bury, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China. The General Standard for Civil. Service Recruitment Health Examination; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2005. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2005-11/03/content_90833.htm (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Beijing Newspaper. Prohibiting Using the Health Examination Standard to Refuse Persons with Disabilities; Beijing Newspaper: Beijing, China, 2017; Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/163225357_616821 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Gooding, C.; Casserley, C. Open for all? Disability discrimination laws in Europe relating to goods and services. In Disability Rights in Europe: From Theory to Practice; Lawson, A., Gooding, C., Eds.; Hart: Oxford, OR, USA; Portland, OR, USA, 2005; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, L. Such as in the disability discriminatory legislation of Australian and UK, the “direct discrimination”, “indirect discrimination” and “reasonable accommodation” are all clearly defined. In Legal Rights and Protection of People with Disabilities in the Workplace: Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States; The Swiss Institute of Comparative Law: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 26–30, 177–178. Available online: https://www.isdc.ch/media/1838/e-avis-2019-17-19-019-disabilities-in-workplace.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- The United States Congress. ADA AMENDMENTS ACT OF 2008(PL 110-325 (S 3406)); The United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.eeoc.gov/statutes/ada-amendments-act-2008 (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- The Legal Daily is a China state-owned newspaper under the supervision of the Central Commission for Political and Legal Affairs that is published in China and primarily covers legal developments. In It’s the Time to Introduce an Employment Anti-Discrimination Law; The Legal Daily: Beijing, China, 2016; Available online: http://npc.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0126/c14576-28084978.html (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF). Main Functions of the China Disabled Persons’ Federation; CDPF: Beijing, China, 1990; Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/zzjg/ (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF). Zhou Changkui: Thirty Years of China Disabled Persons’ Federation, Soaring again in Refreshing Reform; CDPF: Beijing, China, 2018; Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/yw/ldjh/201811/t20181130_642829.shtml (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ministry of Finance; State Tax Bureau; China Disabled Persons’ Federation. Measures for the Administration of Collection and Payment of the Disability Employment Security Fund (No.72 [2015] of the Ministry of Finance and the State Tax Bureau); Ministry of Finance; Finance and the State Tax Bureau: Beijing, China, 2015. Available online: http://www.chinatax.gov.cn/chinatax/n810341/n810765/n1465977/201510/c1967355/content.html (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Wang, Q.X.; Shi, C. Reviews and reflections on 70 years labor law in New China. Seeker 2020, 3, 118–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Deng, J. The paradigm transformation of the labor law in China. Politics Laws 2009, 7, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.Y. The Contract Law: Constructing and developing the harmonious and stable Labor relations. J. Renmin Univ. China 2007, 5, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B.H. The ten unbalanced issues of the China Labor Contract Law. Explor. Free Views 2016, 4, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.Y. The balance between control and relaxation of dispatched employees in China—Studies on the Article 58 Paragraph 2 of the Labor Contract Law of China. Law Sci. 2014, 7, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Labor Contract Law (2012 Amendment) (Order No.73 [2012] of the President); Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress: Beijing, China, 2012. Available online: http://www.lawinfochina.com/display.aspx?id=13222&lib=law&SearchKeyword=&SearchCKeyword=%c0%cd%b6%af%ba%cf%cd%ac%b7%a8 (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- OECD. Indicators of the Strictness of Employment Protection—Individual and Collective Dismissals in 2012 (Regular Contracts); OECD: Paris, France, 2012; Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EPL_OV (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- People’s Daily. China’s Social Security Contribution Rate is not the Highest in the World: Social Security and Pension Insurance Survey; People’s Daily: Beijing, China, 2012; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.H. Private Employment Agencies and Labor Dispatch in China; The International Labor Organization (ILO) Sector Working Paper No. 293; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---sector/documents/publication/wcms_246921.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Interim Provisions on Labor Dispatch; Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security: Beijing, China, 2014. Available online: http://www.mohrss.gov.cn/gkml/zcfg/gfxwj/201401/t20140126_123297.html (accessed on 9 June 2020).

- Xie, Z.Y. The reasons and resolutions of the regulatory failure of labor dispatch. Glob. Law Rev. 2015, 1, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.Z. Authoritative Report States That “Dispatched Employees” Reaches 60 Million and the National Federation of Trade Unions Proposes to Amend the Labor Contract Law; The Economic Observer Newspaper: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, W.Z. Studies on the several issues of “Single Ruling System” in labor dispute. J. Shandong Trial 2010, 2, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.Y. Comments on the Labor Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law. Acad. Bimest. 2008, 6, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.Y. The concept, system and challenge of addressing the labor disputes in China. Chin. J. Law 2008, 5, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF). The 2013 Disability Status and Wellbeing Process Monitoring Report; CDPF: Beijing, China, 2014; Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/sjzx/jcbg/201,408/t20140812_411000.shtml (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Qiu, J. Tenth anniversary of the Labor Contract Law series (eleventh): Research on the labor dispatch in the “labor Contract Law”. China Labor 2018, 11, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

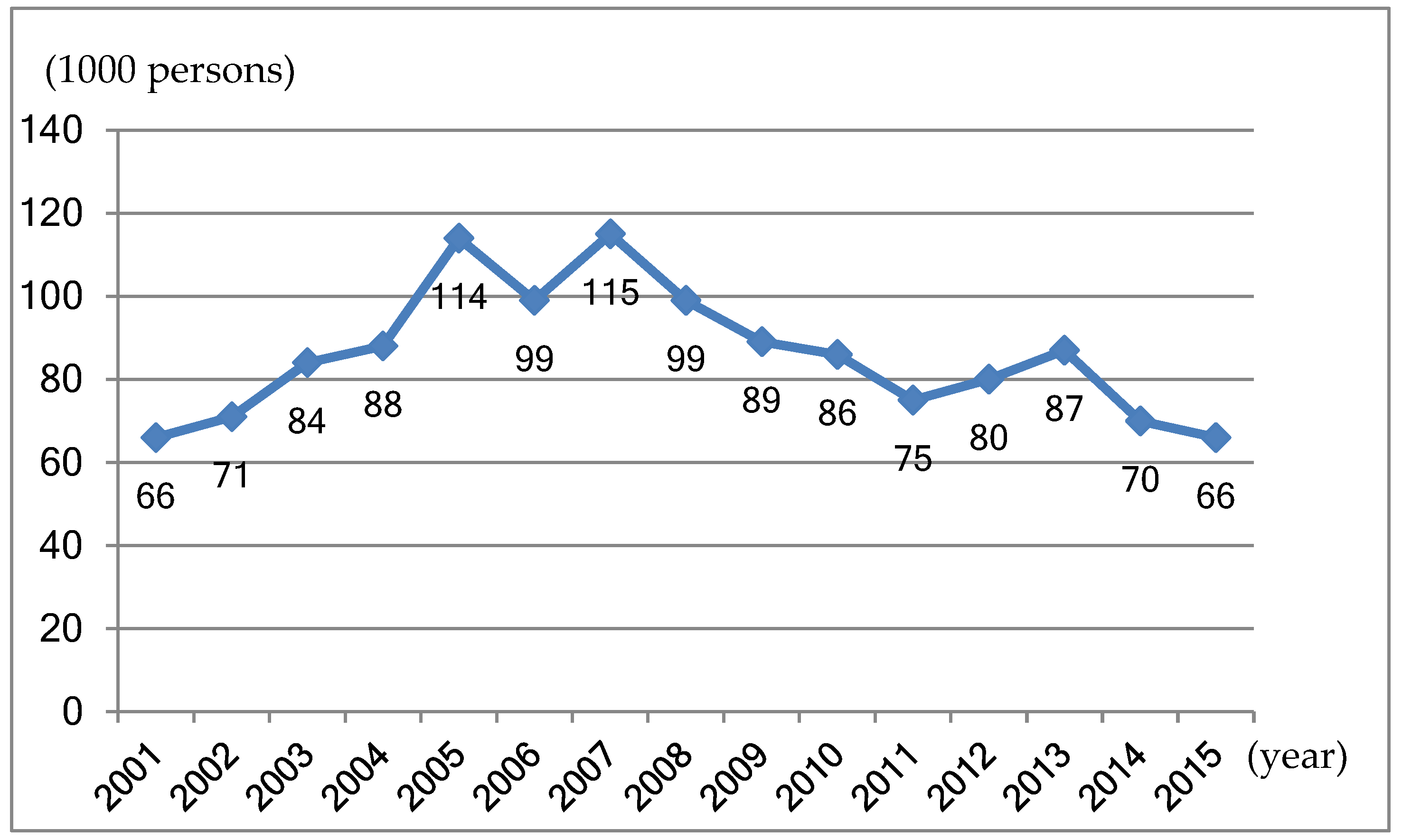

- China’s Disabled Persons Federation (CDPF). The Disability Cause Development Statistical Communiqué in 2001–2015; CDPF: Beijing, China, 2014; Available online: http://www.cdpf.org.cn/sjzx/tjgb/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Ministry of Finance. Ministry of Finance. Ministry of Finance Annual Statistic in 2010–2014; Ministry of Finance: Beijing, China, 2014. Available online: http://www.mof.gov.cn/index.htm (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- OECD. Transforming Disability to Ability: Policies to Promote Work and Income Security for Disability People; OECD: Paris, France, 2003; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Waddington, L.; Diller, M. Tensions and coherence in disability policy: The uneasy relationship between social welfare and civil rights models of disability in American, European and international employment law Symposium. In Principles to Practice: Disability Rights Law and Policy International and National Perspectives; Transnational Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 241–282. [Google Scholar]

- Priestley, M. Disability. In Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State; Castles, F.G., Leibfried, S., Lewis, J., Obinger, H., Pierson, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; p. 419. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams, C.; Corby, S. Then and now: Disability legislation and employers’ practice in the UK. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2007, 45, 556–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M. Quota Systems for Disabled Persons: Parameters, Aspects, Effectivity; European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, J.; Benard, M.; Dycker, S.D.; Fina, V.D.; Kühnel, V.; Mayr, M.; Nadakavukaren, K. Legal Rights and Protection of People with Disabilities in the Workplace: Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States; Swiss Institute of Comparative Law: Dorigny, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.isdc.ch/media/1838/e-avis-2019-17-19-019-disabilities-in-workplace.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

| Country | Employee (%) | Employer (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 9.9 | 32.68 | 42.58 |

| Germany | 20.43 | 20.85 | 41.28 |

| Italy | 9.19 | 31.78 | 40.97 |

| Poland | 22.71 | 17.38 | 40.09 |

| China | 11 | 29 | 40 |

| Belgium | 13.07 | 24.8 | 37.87 |

| Spain | 6.25 | 31.08 | 37.33 |

| India | 13.75 | 22.36 | 36.11 |

| Russia | 0 | 30.2 | 30.2 |

| Brazil | 8 | 21 | 29 |

| Sweden | 7 | 20.92 | 27.92 |

| Japan | 13.12 | 13.77 | 26.89 |

| U.S. | 7.65 | 9.7 | 17.35 |

| South Korea | 7.79 | 8.74 | 16.53 |

| Canada | 6.73 | 7.44 | 14.17 |

| Mexico | 2 | 8.6 | 10.6 |

| Thailand | 5 | 5.2 | 10.2 |

| Indonesia | 2 | 7.24 | 9.24 |

| Year | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of the Total Persons with Disabilities | |||||||

| Illiterate | 42.4 | 42.1 | 41.8 | 40.9 | 37.7 | 36.9 | 36.3 |

| Primary School | 35.1 | 35.0 | 34.8 | 35.2 | 36.9 | 37.6 | 38.0 |

| Junior Middle School (Secondary School) | 15.8 | 15.9 | 16.5 | 16.7 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 18.4 |

| Senior Middle School (High School) | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Technical Secondary School | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Junior College | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Undergraduate and Above | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Conflicts | Mainstream Labor Market | Quota Scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Labor contract | Avoid signing labor contract | Sign a labor contract with the disabled person for a term of at least one year. |

| The calculation of the total employees | Prefer dispatched employees | Dispatched employees are included in the calculation of the total employees of employment service agencies. |

| Social insurance and housing provident fund contributions | High labor cost for the employers | Pay social insurance and housing fund contributions duly and fully. |

| Single Ruling System | Preferring protection for employees | Special labor protection and workplace condition (reasonable accommodations) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, Y.; Li, P. Employment Legal Framework for Persons with Disabilities in China: Effectiveness and Reasons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144976

Hao Y, Li P. Employment Legal Framework for Persons with Disabilities in China: Effectiveness and Reasons. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):4976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144976

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Yuling, and Peng Li. 2020. "Employment Legal Framework for Persons with Disabilities in China: Effectiveness and Reasons" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 4976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144976