Conventionally, communist China has been regarded as an advanced gendering regime that seeks to use the communist gender ideology on women’s emancipation to reform and substitute for traditional patriarchal Confucian society [

18]. As Mao’s verbal assertion, “Women hold up the half sky”, vividly demonstrates, the new Chinese government after the founding of the People’s Republic endeavored to establish a more egalitarian country from the gender perspective. Even the Chinese constitutions from different episodes guaranteed, and continue to guarantee, full equal rights between men and women in the socialist republic [

19]. However, investigating contemporary welfare arrangements in the Chinese welfare state reveals that social inequalities between genders still exist, and the gender welfare gap has perpetuated. Moreover, gender-related social welfare stratification has been further sustained and even promoted in a highly masculine welfare state. There is a remarkable discrepancy between declaratory semantics and the real praxis concerning gender equality and gender welfare.

3.1. The “Silent Reserves” and Their Contributions to (Unpaid) Care Work

Traditionally, family chores and care work, including childcare, elderly care, and the care of disabled family members, have been widely regarded as tasks for women. However, in modern welfare states, and especially in Scandinavian countries, female care work and services are considerably socialized and collectivized. The key issue is how and to what extent female care work can be recognized as a social contribution by a state’s public social policy. Another criterium is to see how and to what extent women can be relieved from household activities and to what extent they can participate in the labor market despite their care work within households.

The recently published report by the ILO, “Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work” (2018) [

10], has constructed a panorama of the unpaid work of women around the globe. Based on data and the estimation of ILO that include all continents and countries, it identifies a global problem of unpaid work of women. Despite the universality of this problem, gender-based inequality varies among world regions significantly. For instance, men in the Asia-Pacific region perform the lowest proportion of unpaid work within households, amounting to only 1 h and 4 min per day. From the perspective of nation states, men from Pakistan spend the least time in unpaid work at home, amounting to just 28 min; in India, it is 31 min. The mothers of children below 6 years old have been plagued by the most severe “employment penalty”; the employment rate of this group is only about 47.6% worldwide [

10]. According to the ILO report, most of the countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America have not yet launched any kind of public long-term care protection systems, relegating care work to the realm of unpaid work mostly performed by women.

As a member of the Asia-Pacific region, China has experienced similar problems and gender-based inequalities. Applying the data and the estimation provided by the 2018 ILO report, we construct an analytical overview of women’s contributions to care work in China that is informed by the theoretical discussion on gendering welfare states in the previous section.

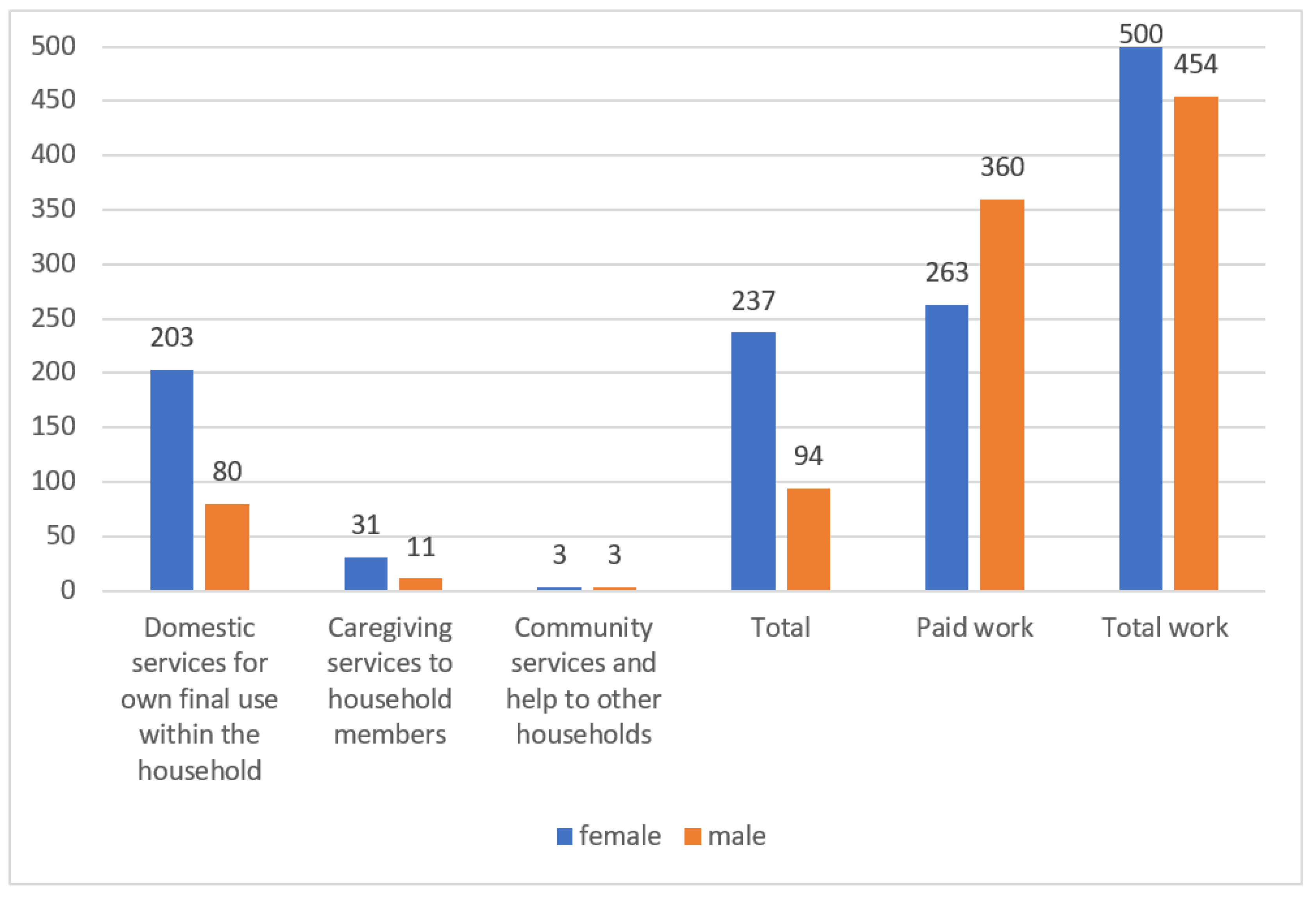

According to the time spent in the three main categories of unpaid home chores—“domestic services for one’s own final use within the household” (such as household accounting and management, food and meal management and preparation, cleaning and maintenance of one’s own dwelling and surroundings, etc.), “caregiving services to household members” (childcare and instruction, care for dependent adults, help for non-dependent adult household and family members, etc.), and “community services and help to other households”—the gender differences in China can be clearly delineated: the time spent by women for domestic services in China is 203 min per day, the time spent by women on caregiving services to household members is 31 min each day, and the time spent on community services is 3 min each day. In total, the time spent by women in these three categories amounts to 237 min per day. By comparison, men spend 80 min each day for domestic services, 11 min for caregiving services at home, and 3 min for community services; the total amounts to 94 min. The average time that Chinese women spend on domestic household work and caregiving services is three times as high as the men’s time investment. The time spent on paid work by women amounts to 263 min per day; for men, it is 360 min. However, if we add the time spent on both paid and unpaid work, women spend in total 500 min per day, which is surprisingly higher than men, who spend in total 454 min (see

Figure 1). The women’s share of time spent on unpaid care work amounts to 71.6%, while the men’s share is only 28.4%: more than 43% lower than the women’s contribution (see

Figure 2). The share of time spent on unpaid work as a proportion of total work time by women is 47.4%; for men, the percentage is only 17.6 (see

Figure 3).

Among the female unpaid carers who live with their care recipients (such as elderly people who need care and disabled family members), 39.1% are outside of the labor force, 58.3% are employed, and 2.7% are officially registered as “unemployed”. In comparison, among male unpaid care workers living with their care recipients, 14.9% are outside of the labor force, 83.4% are employed, and 1.7% are “unemployed” (see

Figure 4). The employment rate of female caregivers living with their care recipients is 25% lower than the male employment rate. In contrast, the proportion of female caregivers living with their care recipients drops many more women from the labor force than men; the difference is nearly three times as high. For the caregivers not living with their care recipients, the gender gap narrows slightly, 39.7% of women and 23.9% of men are outside the labor force, while 57.6% of women and 73.4% of men are employed (

Figure 4). The gap in the employment rate narrows to less than 16%; nevertheless, it is remarkable.

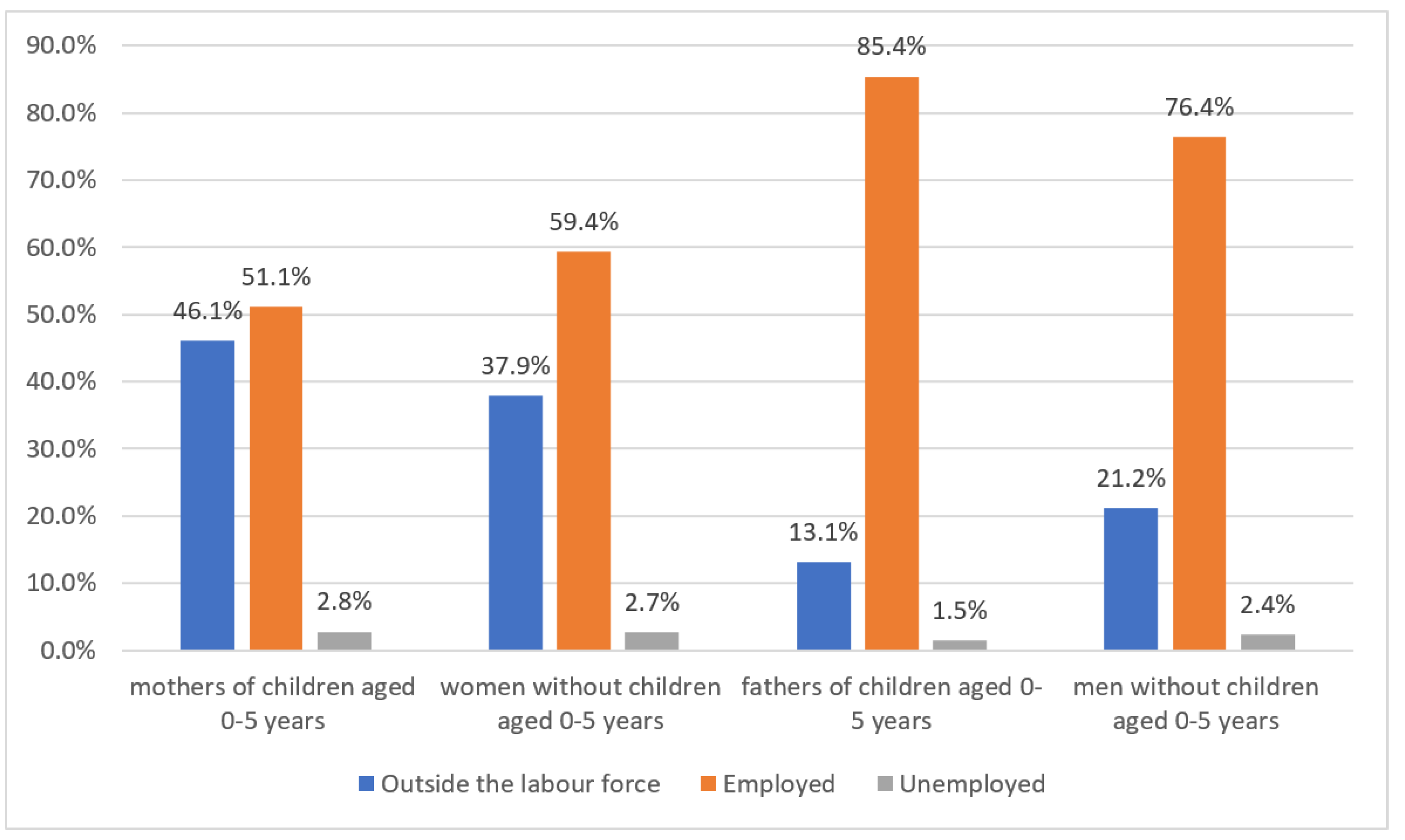

More specifically, childcare is a factor that influences women’s employment significantly. Among mothers of children aged 0–5 years, 46.1% are outside of the labor force, 51.1% are employed, and 2.8% are registered as “unemployed”. In comparison, the women without children aged 0–5 years are situated in a more favorable position; 37.9% are outside labor force, 59.4% are employed, and 2.7% are “unemployed”. Compared to fathers of children aged 0–5 years, 13.1% are outside of the labor force, 85.4% are employed, and 1.5% are counted as “unemployed”. Among men without children aged 0–5 years, 21.2% are outside of the labor force, 76.4% are employed, and 2.4% are “unemployed” (see

Figure 5). Between these two selected groups—mothers and fathers of children aged 0–5 years—the discrepancy in employment status is most significant: the employment rate of men is 34% higher than for women, while the percentage of residents dropping out of the labor force among women is more than 3.5 times higher than that of men. However, the gender-related gap of employment status between non-mothers and non-fathers of children aged 0–5 years narrows to 17%. In the arena of childcare, the Chinese welfare state again approaches the traditional conservative–corporatist welfare state in Continental Europe. The facilities for childcare are generally insufficient and the care of children is completely individualized; in other words, individual family matters have remained outside the scope of general public welfare since the economic reform in China.

With regard to the reasons for being outside the labor force by sex, the differences are again remarkable: 35.8% of women leave the labor market for unpaid care work, while 20.6% leave for personal reasons such as education, being sick, or being disabled. By comparison, only 14.1% of men drop out of the labor market for unpaid care work, and 33.5% leave because of education, sickness, or disability. The percentage of women outside of the labor force due to unpaid care work is thus 2.5 times higher than men in the same category (see

Figure 6). If we consider the urban–rural gap, in urban China, 24.5% of female unpaid carers are outside of the labor force, 71.6% are employed, and 3.8% of them are registered as “unemployed”. In rural areas, 54.1% of female unpaid carers are outside of the labor force, 44.4% are employed, and 1.5% are officially counted as “unemployed”. This urban–rural comparison demonstrates that the percentage of rural female unpaid carers outside of the labor force is twice as high as among women in Chinese cities. The percentage of women who have combined unpaid care and employment in urban areas is 27% higher than in rural areas. Rural women are quantifiably more prone to leaving the labor market due to unpaid care work (see

Figure 7). Due to the mass out-migration of the young and middle-age male population from the rural areas, the rural women are much more overloaded by elderly care than the urban women.

The data-based analysis on care and unpaid work by sex reveals that women in China are proportionally much more exposed to the “employment penalty” and risk of unemployment due to unpaid care work for their elderly family members and other kinds of home chores. Since China has still not established formal public long-term care protection programs, as in Scandinavian regions and in Germany, and additionally, due to the complete individualization of childcare within households, Chinese women remain “net silent contributors” to Chinese welfare states. Moreover, millions of Chinese women must leave the labor market because of the heavy burden of care responsibilities within households. With the rapid demographic aging and super-aging and the rising demand of elderly care [

20], women’s employment status will deteriorate.

3.2. Women’s Pension Entitlements in China

Within a social insurance system, the pension is closely linked to individual employment history and the pension insurance contributions of employees. The benefit level of an old-age pension depends overwhelmingly on the period and amount of these contributions. A gapless and comprehensive employment biography contributes to full pension entitlement and a generous pension; in contrast, a patchy and an incomplete employment biography results in a rudimentary pension entitlement and a fragmentary and precarious pension [

21,

22]. Since the periods outside the labor force for women are normally much longer than for men, because of the women’s share of care work within the household, women are much more prone to low and marginal pensions and old-age poverty, unless the welfare state takes gender-specific social protection measures to recognize their domestic care work as social work and relieve them at least partially from their home care activities. In traditional Bismarck social insurance programs, most women were precluded from pension entitlements and did not obtain an independent pension, since their sources of income came overwhelmingly from their husbands’ participation in the labor market. In case of the husband’s death, a woman could receive a widow’s pension. However, women’s pension status in Germany has been remarkably improved since the 1970s, with the introduction of a series of gender-related pension arrangements that have elevated the women’s social status in pension entitlement significantly, facilitating a pension-related independence for women [

13].

From the perspective of gender-related inclusivity in pension participation, the gender gap in the degree of coverage for Chinese pension schemes has considerably narrowed since the early 2000s. According to the “Report of the Third Survey of Chinese Women’s Status”, conducted by the Chinese Women’s Association (CWA) and the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) in 2010 [

23], 75.9% and 73.3% of urban male and female residents (with non-agricultural Hukou) have participated in old-age pension programs respectively; the gender gap is only 2.6%. For the rural population (with agricultural Hukou), 32.7% and 31.1% of rural male and female residents have participated the old age pension, and the gender gap is only 1.6%. In the “Report of the Second Survey of Chinese Women’s Status”, the data from urban areas showed that in 2000, 65.9% of male residents and 60.5% of female residents were covered by old age pension programs, and the gender gap in coverage was about 5.4% [

23]. The gap has narrowed because the Chinese government has introduced non-contributory and tax-financed basic pension programs since 2009 for urban and rural residents who had not been insured by previous social insurance programs [

22]. The introduction of a universal pension scheme has considerably improved women’s pension entitlements since they are no longer connected to social insurance contributions; thus, they are also disconnected from employment status in the labor market. Women who are not in the labor market benefit from the non-contributory pension, which is not based on previous work achievements.

However, if judged according to benefit level, the impact of this non-contributory pension on remedying the gender-related pension gap is still limited. Despite the introduction of the non-contributory basic pension for urban and rural residents, its low benefit level has only a marginal effect. Initially, the central government set up a minimum benefit level for the basic pension in the amount of 55 RMB (6.94 €) nationwide, but now, it has been gradually raised to 88 RMB (11.10 €) nationwide, and local governments can top up this minimal pension according to local fiscal resources. In most regions, the benefit level of the basic pension varies mostly from 100 RMB (12.61 €) to 400 RMB (50.44 €). Due to the comparatively low level of the basic pension, it has only limited impact on improving the income and social security of female seniors. The contribution-financed old age pensions still play a significant role in safeguarding the livelihood of senior citizens. In short, the gender gap in pension insurance payments persists, and it is still significant.

According to the calculations by Gao and Pan, the old age pension income of Chinese women is only 56.23% of men’s income [

5]; thus, women are much more exposed to social risks and old-age poverty than male pensioners. According to the “Report of the Third Survey of Chinese Women’s Status”, the average labor income of women in urban and rural areas, respectively, is only 67.3% and 56.0% of the average income for men. The percentages of women in the low-income group in urban and rural areas are 59.8% and 65.7% respectively, which are 19.6% and 31.4% higher than male employees. Since the Chinese old-age pension insurance in urban areas consists of two pillars—the social pooling financed by a pay-as-you-go financial model and individual pension accounts financed by mandatory individual pension payments consisting of 8% of personal gross income—the lower income of women is automatically related to lower pension payments into the individual pension accounts. Consequently, due to the gender wage gap, women have lower average pensions than men. Considering that China still adheres to an outdated model of retirement age, 60 years for men and 50–55 years for women (The retirement age for men and women was established after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. At that time, life expectancy in China was comparatively low. Female employees in enterprises retired regularly at 50 years old and female civil servants and female staff in public institutions usually retired at 55 years old. This model of very early retirement for women has persisted to the present day and inevitably, it has a significant impact on the benefit level of women’s pensions.), the early retirement age for women further diminishes the contributions paid into their individual pension accounts. Generally, female pensioners in China receive much lower amounts from the pension insurance system than male pensioners. Since women have a longer average life expectancy than men, the gender-related pension injustice becomes even more salient.

The population censuses in China have also included gender-related data on social security and old-age pension income. According to the Sixth Population Census of China (2010), among the population aged 60 and over nationwide, 28.89% of men’s income came from old-age pension payments, compared to 19.58% for women. In urban areas, the share was 74.21% for men and only 59.07% for women. At the level of townships, the figures were 35.24% and 17.85%, respectively. In rural areas, only 2.09% of women’s income came from old age pension payments; the percentage for rural men was three times higher—7.19% (see

Table 1). Due to these comparatively low pension levels, elderly women have become more dependent on other income sources outside the institutional state pension to sustain their livelihoods, and the elderly women in China rely much more upon the supply of family members than elderly men. An independent female pension is still a big social question in the current Chinese social protection.