1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognises poor housing as one of the main social causes of ill health [

1,

2] and extensive evidence has demonstrated improvements in health associated with improvements in housing and living environments since the late 1800s [

3,

4,

5].

While Australia is an economically developed country with a high standard of living [

6,

7,

8], poor housing in Aboriginal communities continues to be linked to the compromised health status of Aboriginal Australians since early last century [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

There are around 800,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, representing 3.3% of the total Australian population. Whilst in remote areas there are higher proportions of Aboriginal Australians, one-third of the Australian Aboriginal population lives in New South Wales (NSW), the most populous state in Australia [

19,

20]. The NSW state health authority (NSW Health) has been delivering Housing for Health (HfH) projects with Aboriginal communities across NSW since 1997. HfH aims to improve the health status of Aboriginal people, particularly children, by assessing, repairing or replacing “health hardware” (particularly plumbing and electrical items) in houses to ensure they are safe and support occupants to practice healthy living. Health hardware in the context of HfH is defined as “the physical equipment needed to give people access to the health giving services of housing” [

21].

HfH is a structured process for surveying and fixing houses, developed by Healthabitat, a not-for profit organisation, in the early 1990s [

22,

23]. It has since been used throughout Australia and internationally [

9,

24] and adopts a “no survey without service” approach to testing, recording, repairing and reporting at each survey. The “no survey without service” approach means no survey data is collected without a service being provided, such as making immediate repairs to items that require urgent attention [

22].

In 1997 an interagency environmental health committee of NSW government agencies funded a trial HfH project in one discrete Aboriginal community in Northern NSW that demonstrated measurable improvement in the condition of those houses and ability to support healthy living. Consequently, a jointly funded program by NSW Health and the NSW Governments’ 10-year Aboriginal Communities Development Program (ACDP) expanded HfH to other NSW Aboriginal communities—usually a small town or a neighbourhood in a larger town [

25]. An evaluation at the end of the ACDP funding cycle demonstrated positive health outcomes and subsequently the program was recurrently funded by NSW Health and funding increased. The NSW HfH program is managed centrally by NSW Health’s Aboriginal Environmental Health Unit and delivered jointly with regional NSW Public Health Units (PHUs), in partnership with the Aboriginal communities. The HfH program and financial management is guided by NSW state government policies and procedures.

This paper aims to describe the development of the HfH program in NSW, provide an overview of the program methodology and an analysis of program data over 20 years, and discuss the benefits and limitations of the program.

3. Results

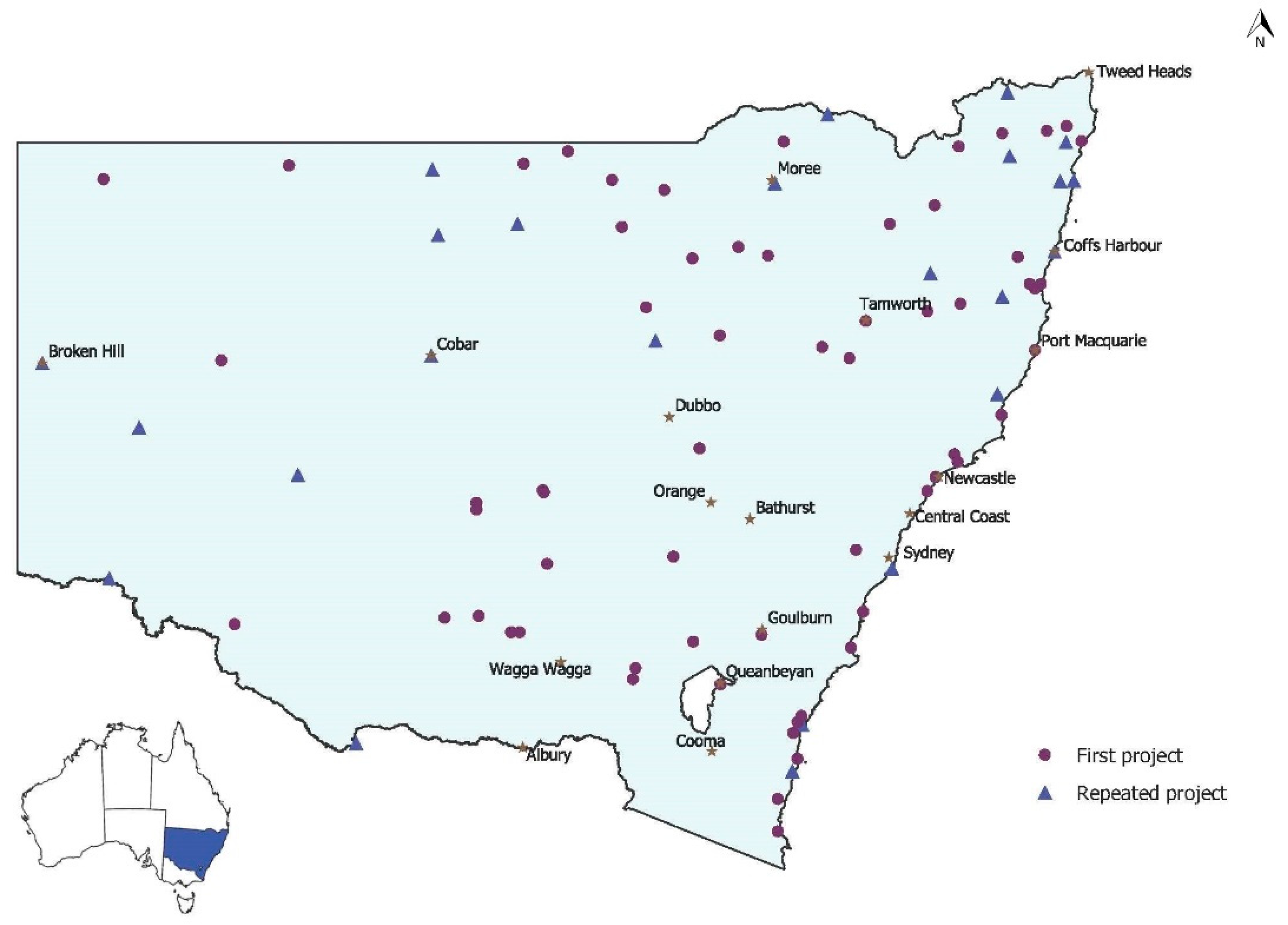

Over the 20-year period (1998–2017), the NSW Housing for Health (HfH) program conducted 113 HfH community projects (or interventions) in 3670 houses with a resident population of 14,609 people. In total, 88 communities (2791 houses) received at least one HfH project from 1998 to 2017. Of these 88 communities, 24 (802 houses) had a second project between five and 17 years later. One community had a third project implemented but it is not included in this analysis.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of communities where HfH projects were conducted across NSW from 1998 to 2017, including those communities visited more than once. There is a wide distribution of HfH projects in communities across the state in urban, rural and remote areas. The HfH program has reached around 70% of houses in the NSW Aboriginal community housing sector over this time.

Table 1 summarises this information by five-year intervals. The results show the number of projects, houses and residents (recorded at SF1) in communities that received one or more HfH projects.

Figure 2 shows the average percentage of houses where all CHLPs were fully met at SF1 and SF2 for all NSW projects by 5-year intervals. (

Table A6 in

Appendix E summarises data for

Figure 3). Trend analysis shows increasing improvement at SF2 over time. However, the CHLP related condition of houses before the project (SF1) remained consistently low (below 40% average across CHLPs) over the past 20 years. This general trend is reflected in nearly all the critical HLPs (represented in

Appendix D).

Figure 3 shows changes in the CHLPs (the most important items needed to support safe and healthy living) between SF1 (red bars) and SF2 (blue bars) for all projects completed in NSW over the past 20 years. The CHLP categories are prioritised from left (highest) to right. (See

Appendix E Table A5 for data tables for

Figure 3). The columns represent the percentage of houses that met all criteria (100% score) for each CHLP category in all HfH projects (

n = 112). If one or more criteria failed in a house, the house was not considered to adequately support that CHLP item.

At the initial survey (SF1), safety in houses was low, particularly electrical safety (7.5%), structure and access (23%) and fire safety (29%). For those houses with gas, just over half (56%) met the safety requirements. With regard to washing people, only 39% of all houses had all items in the shower working and two thirds of houses had a place to wash a small child with all hardware working (such as a bath, large basin or laundry tub with washing machine by-pass). Only 29% of houses had laundry facilities to support the washing of clothes and bedding. This includes the hardware and space to install a washing machine safely but does not include the washing machine itself as this is considered a tenant responsibility in social housing. Only two thirds of houses had flush toilets working properly, and 21% had all drainage working. Improving nutrition is assessed by whether houses support the ability of residents to prepare, cook and store food safely. Only 9% of houses had all items in this CHLP category working at SF1.

Chi-squared analysis (P < 0.01) revealed significant improvement in the percentage of houses meeting each CHLP from SF1 to SF2 in all categories. Following SF2, a score of at least 75% was attained for all but two of the CHLPs, with four CHLPs exceeding a score of 90%. The biggest improvement was in electrical safety, with only 7% meeting this CHLP at SF1 and 87% at SF2. Whilst the ability to store, prepare, and cook food was improved more than 4-fold, only 39% of houses had all items working at the end of the projects.

Figure 4 presents data on the reasons tradespeople recorded for repairing 63,648 items identified by the survey during the 20-year study period. Across NSW Aboriginal community housing, 84% of items repaired were routine maintenance issues. Faulty design or workmanship accounted for 11% of failures, with 5% of items fixed as a result of damage by the tenants.

Figure 5 shows the CHLPs for 24 communities where a repeat project was implemented in the second decade of the program. The red and dark blue bars show the percentage of houses meeting each CHLP at the first project SF1 and SF2, respectively. The orange and light blue bars show the percentage of houses meeting each CHLP at the second project SF1 and SF2, respectively. (See

Table A7 in

Appendix E for Data Tables for

Figure 5).

In both visits, significant improvements in houses were made between SF1 and SF2. The SF2 results for all CHLPs in the second HfH projects within the same community were higher than SF2 in the first HfH projects in those communities. All CHLPs except Gas Safety and Structure and Access followed a similar pattern: the lowest house function was recorded at SF1 of the first HfH project. These increased significantly by SF2. In the five to 17 years between the first and second HfH projects in these communities, the functionality of the houses dropped, but overall not to the level of the first HfH project in these communities, indicating some of the improvements from the first project may have been sustained in these 24 communities that had a second HfH project.

4. Discussion

This report highlights the sustained improvements to housing within NSW Aboriginal communities as a result of the NSW Housing for Health (HfH) program over a 20-year period from 1998 to 2017. The research demonstrated significant improvements in the condition of houses and the ability to meet critical healthy living priorities (CHLPs) due to the HfH project intervention (

Figure 3). Not all houses reached 100% for all the CHLPs reported in this paper, but more detailed analysis of the data showed there were still measurable improvements in each house (see

Appendix C).

Most CHLPs achieved greater than 75% compliance after the HfH project intervention. However, results are generally lower for the lower priority CHLPs largely because of HfH program budgetary constraints restricting improvement on expensive items.

Each CHLP comprises a set number of items and a house must pass all these items to achieve that CHLP goal. Occasionally, achieving a maximum score for all CHLP items is beyond the scope of the HfH program funding and not all items are fixed. For example, fire safety in all houses was upgraded to current standards for smoke detection, but in some houses, security screens had been permanently fixed to the building frame, increasing security but preventing egress (fire escape) from windows.

Whilst the facilities to store, prepare and cook food were improved more than four-fold due to the HfH project intervention, only 39% of houses had all items working after the intervention. Budgetary constraints limited the ability to improve all items within this CHLP, particularly in the first decade of the program.

Appendix B shows the separate criteria for this CHLP in more detail. Increased HfH funding allocation in the second decade of the program is likely to have contributed to the measurable improvement in this category over time (as shown in

Appendix D).

The results of Survey-Fix2 (SF2) are a measure of the effectiveness of the HfH project intervention to improve house function over the past 20 years. Trend analysis of the overall SF2 data post-intervention (

Figure 2) indicates the HfH program has become more effective over time. This is most likely a result of improved targeting of items for repair by HfH project managers and some increased funding.

Appendix E shows that this same trend of program efficiency is consistent across each of the CHLPs.

Evaluation of house function is built into the methodology of the NSW HfH program for each HfH project but quantifying the impact of the HfH program on health outcomes is challenging. A 10-year evaluation of the program assessed changes in hospital admissions before and after each project. The analysis linked hospital admissions data to all houses in the HfH program over the first decade and demonstrated a 40% reduction in hospital separations for environmentally related infectious diseases for those residents of houses included in the HfH program compared to a control population [

30]. A summary of this evaluation and these results is presented in

Appendix A. Whilst this analysis cannot demonstrate causality between the HfH intervention and reduced disease, it does demonstrate a strong association between these improved house function measures and improved health outcomes [

30]. The significant reductions in hospitalisations found in this assessment occurred in the context of significant improvement in targeted safety and healthy living practice measures over the first decade of the HfH program.

Figure 2 demonstrates even greater improvements in house function over the second decade of the HfH program (2008 to 2017) compared to the first decade (1998 to 2007), indicating the same or possibly better health outcomes would likely be continued over the life of the HfH program.

Survey-Fix 1 (SF1) data describes of the condition of housing before any work was undertaken as part of the HfH intervention. The HfH program has surveyed and fixed around 70% of the NSW Aboriginal community housing sector, presenting a picture of the housing condition in the sector over 20 years. The ability of Aboriginal community housing in NSW to support basic safety and healthy living priorities prior to a HfH project was below 40% across all houses (

Figure 2) and trend analysis indicates a lack of significant improvement in the condition of houses in the sector over the last two decades.

The failure of housing management systems is a likely reason for this lack of improvement in house function in Aboriginal communities over the past two decades (see

Figure 4). NSW HfH program data indicates 95% of the repairs made on these houses resulted from a failure of systems to ensure routine maintenance (84%) and adequate checks on the quality of workmanship (11%). Focusing on tenancy management to reduce tenant damage will only address 5% of the issues related to house function in NSW community housing. Our results are consistent with previously published national data (2006) which showed, whilst there were slightly higher rates of tenant damage (10%), the primary cause for house function failure stemmed from a failure of maintenance regimes and quality control [

9].

Although the average condition of houses at SF1 across all 112 HfH projects shows very little change over 20 years, (

Figure 2) the 24 locations that have received a second HfH project have maintained higher house function (at the second project SF1) for most CHLPs (

Figure 5), suggesting a sustainable benefit of the HfH program over time. This finding is consistent with results reported in the 10-year review which showed one community in 2003 where a third survey and fix had been undertaken 2–3 years later to gauge the sustainability of the program, house function had deteriorated slightly since SF2, but only 5% of the original funding was required to bring the houses back to the same standard [

30]. Anecdotally, HfH project managers have reported that higher quality health hardware (e.g., taps) specified by the program was still functioning at the return visit. Whilst high quality materials may cost a little extra, they are likely an investment in sustainable health hardware. Further analysis of the survey and financial data for these 24 projects is planned to identify the sustainability of improvements in individual items.

Data from communities that received a repeat HfH project demonstrates significant improvement in the condition of the houses after each intervention (from SF1 to SF2). The improvement between SF2 results at the end of the first and second interventions is consistent with the general improvements in project delivery over the life of the program, illustrated in

Figure 2.

The results of the HfH program assessment of evidence-based housing safety and health priorities presented here demonstrates significant improvements in the home environments over two decades. For disadvantaged families where unemployment is high, the home environment is often the environment where people spend most of their time. Ensuring the homes’ ability to support health is associated with significant reduction in the rates of infectious diseases, which in turn can reduce the risk factors for many chronic diseases, such as renal and cardiac disease, both of which are overrepresented in the Aboriginal population [

17,

20,

31]. The HfH program also helps ensure the home environment supports practices delivered by health messages through clinical and population health services.

Improving health outcomes should reduce health expenditure on preventable conditions. “The cost of poor housing is borne by the health system” [

32] and, while the extent of the financial benefit to health from the NSW HfH program is yet to be quantified, the relatively small amounts of HfH program funding that supports healthy living is likely to be an investment in health into the future. The benefits of the HfH program are not limited to improvements in house function and health outcomes. The strong engagement with Aboriginal communities throughout the process builds relationships between the communities and the NSW state health authority, as well as local Public Health Units. On the strength of these relationships, other issues of concern to the community, such as drinking water quality or waste management, have been raised and addressed by separate programs. Socioeconomic disadvantage covers a wide range of factors of which a functioning house may only be one. However, for a householder juggling many issues in the home, it can mean one less cause of stress and disempowerment in their life, allowing them the energy to focus on other issues including their health and the health of their family.

Much has been published on the connection of housing and health in the international literature. In the context of industrialised economies, much of the modern literature relates to urbanisation, energy efficiency, temperature control (particularly in cold environments), and indoor air quality issues such as mould and chemical exposures [

33,

34,

35,

36]. There is also a considerable body of literature on improving drinking water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) in the developing country context [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. There is less published internationally on the capability of modern housing to support issues such as safety and WaSH principles. In the Australian context, a number of housing-related papers in the published and grey literature reference safety and healthy living practices as a measure or a best practice standard for housing [

17,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48], but the findings of this paper suggest no assumptions can be made that are adequately addressed in modern public housing, especially in Indigenous communities.