Leadership among Women Working to Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation: The Impact of Environmental Change in Transcultural Moments

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Methods

Ethics Declarations

3. Results

3.1. Sociological Data:

- -

- WL1 was 46 years old, was born in Guinea Bissau, had lived in Spain for 14 years, was separated, and had a son. She actively participated in an association campaigning against FGM.

- -

- WL2 was a native of Kenya who had been living in Spain for 22 years, was separated, and had three children (two boys and one girl). She actively participated in an association campaigning against FGM.

- -

- WL3 was the youngest, at 27 years old, who had been born in Guinea Bissau, had lived in Spain for 15 years, was single, and had no children. She actively participated in an association campaigning against FGM.

- -

- WL4 was 38 years old, had been born in Mali, was married, had three children (one girl and two boys), and had lived in Spain for 12 years. She participated in several associations campaigning against FGM, but was not collaborating with any particular one. She found it most difficult to fight against FGM actively and attributed this to the care of her children and husband.

- -

- WL5 was 61 years old, born in Gambia (capital). She was presently divorced and had lived in Spain since 1974 (45 years). She had five children (three girls and two boys). WL5 participated in several associations campaigning against FGM. She had also become president of a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO).

- -

- WL6 was 49 years old, born in Mali. She was divorced and had lived in Spain since 2001. She had two children (two girls). WL6 participated in an association campaigning against FGM.

- -

- WL7 was 38 years old, born in Guinea Bissau. She had divorced several years ago. WL7 had three children (two boys and a girl). She had lived in Spain since 2002. She participated in several associations campaigning against FGM but was not collaborating with any particular one.

3.2. Female Genital Mutilation and Health Problems

- (a)

- Women interpreted difficulties with urination, urinary tract infections, sexual pain, and problems related to penetration as part of normality. They understood that these problems were not usual after they had interacted with women from other cultures:

- -

- Four of the women said that they had no desire for sex, due to the pain caused during relationships (W1, W3, W5, W7).

- -

- Five women reported that they felt a lot of pain in their sexual relationships (W1, W3, W5, W6, W7) but had thought that the pain was normal.

- -

- All women had problems with arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction.

- (b)

- The women said they had menstrual problems (dysmenorrhea) and genital infection problems:

- -

- Six women claimed to have menstrual problems such as dysmenorrhea and dysregulation (W1, W2, W3, W5, W6, W7).

- -

- Six women had genital infection problems (W1, W2, W3, W5, W6, W7).

- (c)

- Some of the interviewed women had problems during pregnancy and/or delivery (W3 has no sons).

- -

- Four women had problems in pregnancy (W1, W4, W5, W6).

- -

- Three women had problems in delivery (W3, W5, W6).

- (d)

- About the psychological problems associated with FGM.

- -

- All women had psychological problems (anxiety, stress, fear).

3.3. Female Genital Mutilation and Cultural Moments

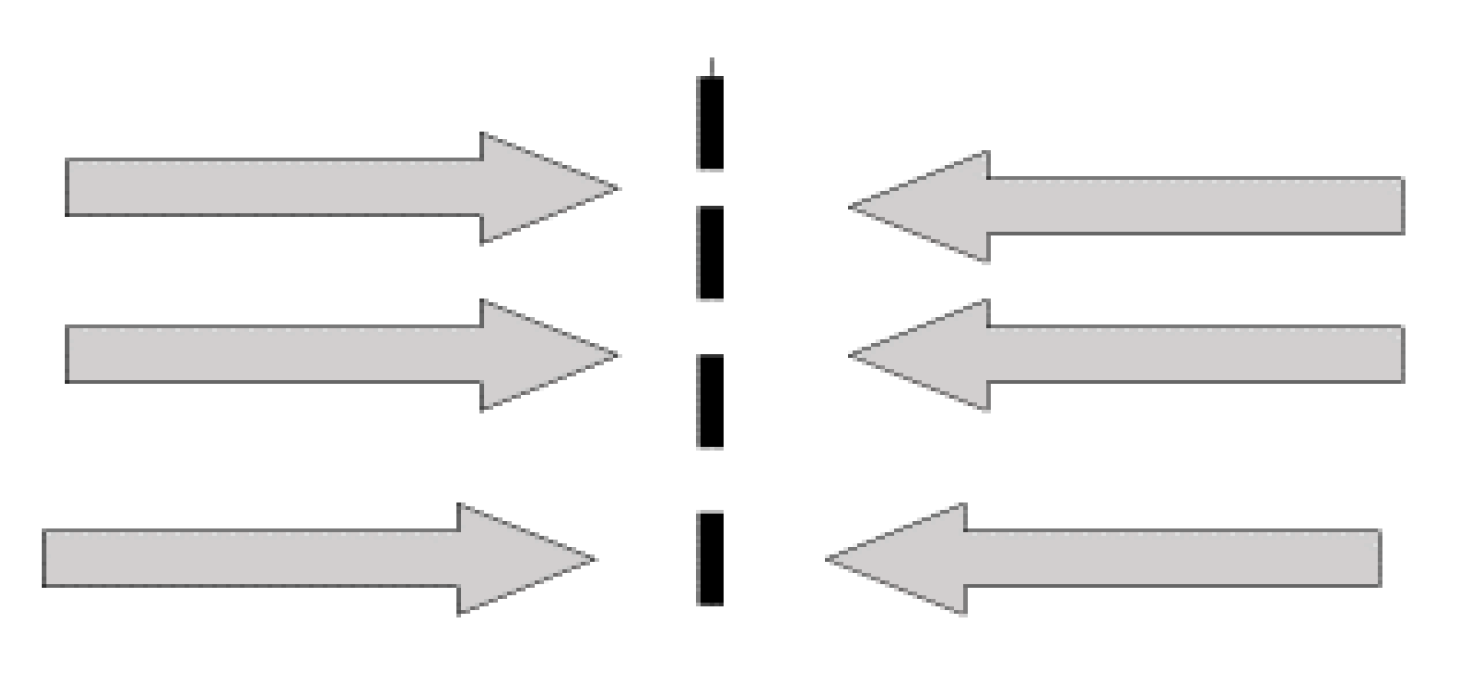

3.3.1. Multicultural Moment: Change of Place without Leaving Cultural Isolation

3.3.2. Intercultural Moment: The Beginning of Communication between Different Cultures

3.3.3. Transcultural Moment: Change of Place Becomes Cultural Change

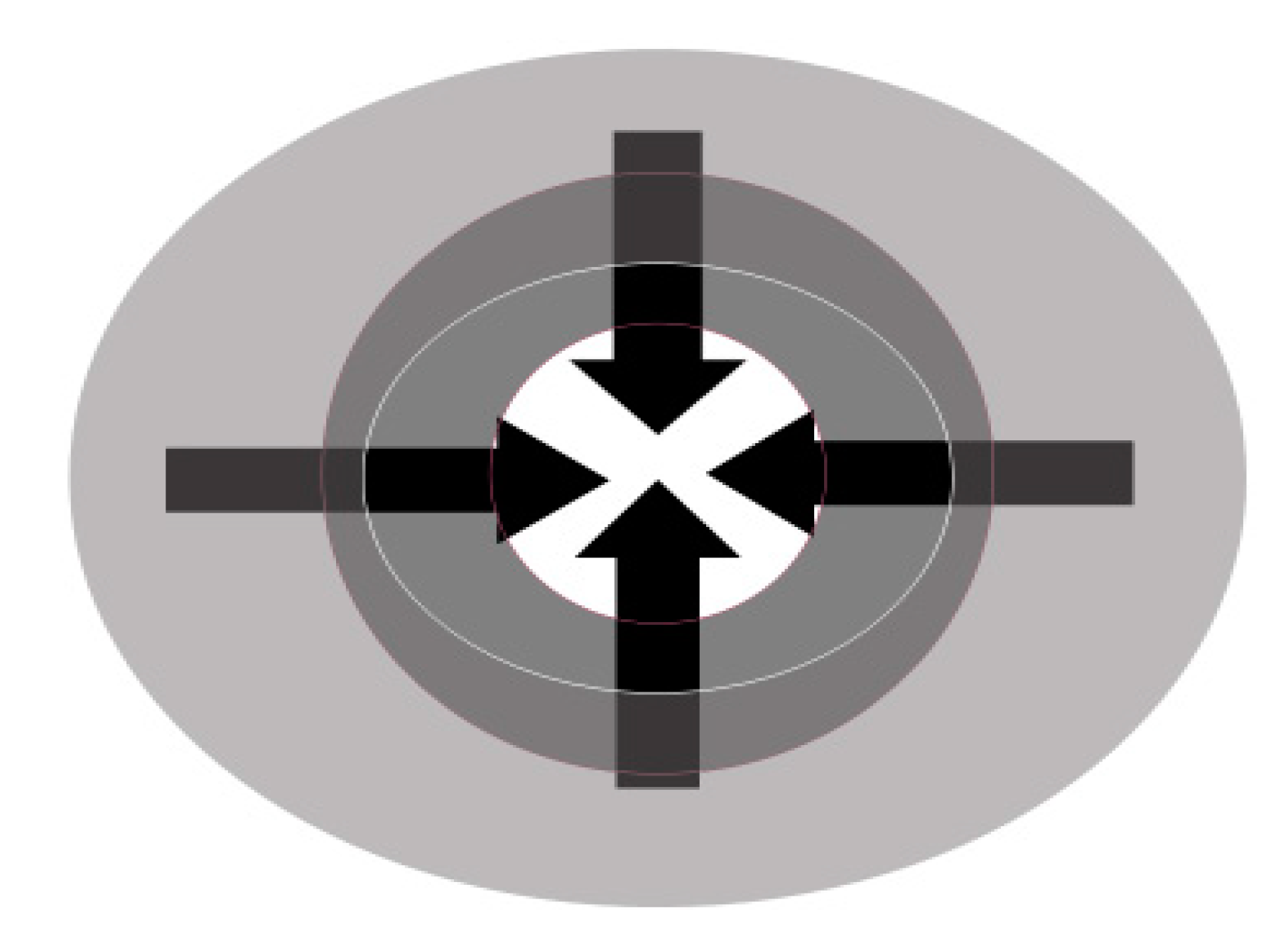

3.4. Female Genital Mutilation from the Perspective of the Dialectical Structural Model of Care

4. Discussion

Limits of Study

5. Conclusions

- -

- Facilitate the empowerment of women by enhancing their integration into associations that support the eradication of FGM (all are working with different associations);

- -

- Transform women into educational agents to raise awareness among migrant women about the reality of FGM. Several programs have already been carried out by women participants in different settings;

- -

- Transform women participants into educational agents to make women in their countries of origin aware of the reality of FGM. A project has already been implemented jointly by WL and members of the group Culture of Care (program of awareness activities against female genital mutilation developed in Guinea Bissau in December 2019);

- -

- Sensitize health professionals through awareness courses on FGM (several courses have already been implemented in different health centers);

- -

- Include programs to raise women’s awareness of the reality of FGM, implemented in associations such as Elche Acoge and other NGOs.

- -

- Phases of the PAR: identify the problem (or DX); design of action plan; execution of the action plan; observation, collection, and analysis of information; reflection and reinterpretation of results; re-planning and re-evaluation of the problem.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSMC | Dialectical Structural Model of Care |

| FGM | Female Genital Mutilation |

| W | Women |

| WL | Women Leaders |

References

- Worsley, A. Infibulation and female circumcision: A study of a little-known custom. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Br. Emp. 1938, 45, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Belay, D.G.; Tiruneh, A.Z.; Kia, T.T. Social and Health Risks of Female Genital Mutilation for Medication and Braveness. Int. J. Risk Conting. Manag. 2018, 7, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A. Knowledge and attitudes of female genital mutilation among midwives in Eastern Sudan. Reprod. Health 2012, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asresash, D.; Abathun, J.S.; Abdi, A.G. Attitude toward female genital mutilation among Somali and Harari people, Eastern Ethiopia. Int. J. Women’s Health 2016, 8, 8557–8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isman, E.; Vanja, C.; Berggren, V. Perceptions and experiences of female genital mutilation after immigration to Sweden: An explorative study. Soc. Reprod. Healthc. 2013, 4, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, S.M.; Galea, S. Is female genital mutilation/cutting associated with adverse mental health consequences? A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siles-González, J.; Reig-Alcaraz, M.; Noreña, A.L.; Solano-Ruiz, C. Critical Thinking and experiences of women who have sufered female genital mutilation: A case study. Easy Chair 2018, 238, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, M. La voz de las Mujeres Sometidas a Mutilación Genital Femenina: Saberes Para la Disciplina Enfermera. 2014. Available online: http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/284894 (accessed on 11 April 2019).

- Jiménez-Ruíz, I. Enfermería, y Cultura: Las Fronteras del Androcentrismo en la Ablación/Mutilación Genital Femenina. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta, A.S. La Mutilación Genital Femenina: Aspectos Jurídico-Penales. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.; López, A. Mapa de la Mutilación Genital Femenina en España 2016. In Antropología Aplicada; Servei de Publicacions Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Care of Girls & Women Living with Female Genital Mutilation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Geneep, A.V. Rites of Passage; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, M.; Pablo, L.; Fernández, P.; Sanchez, J.; Carmen, M.M.; Fernández, G.; Rojas-Tejada., A.J.; Guirado, I.C.; Matilde, G.; García, A.; et al. Estrategias y Actitudes de Aculturación: La Perspectiva de los Inmigrantes y de los Autóctonos en Almería. In Dirección General de Coordinación de Políticas Migratorias; Universidad de Almería: Almería, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reig, M.; Siles, J.; Solano, C. Attitudes towards female genital mutilation: An integrative review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Siles, J.; Solano, C. A mixed-method synthesis of knowledge, experiences and attitudes of health professionals to Female Genital Mutilation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abusharaf, R.M. Female Circumcision: Multicultural Perspectives; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, S. A Community of Women Empowered: The Story of Deir El Barsha. In Female Circumcision: Multicultural Perspectives; Abusharaf, R.M., Ed.; University of Pensylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 104–124. [Google Scholar]

- Thill, M. (Ed.) Socio-Cultural and Legal Aspects of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Transnational Experiences of Prevention and Protection; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, S.A.; Abbas, A.M.; Habib, D.; Morsy, H.; Saleh, M.A.; Bahloul, M. Effect of female genital mutilation/cutting; types I and II on sexual function: Case-controlled study. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushwan, H. Female genital mutilation: A tragedy for women’s reproductive. Afr. J. Urol. 2013, 19, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siles, J. La utilidad práctica de la Epistemología en la clarificación de la pertinencia teórica y metodológica en la disciplina enfermera. Index Enferm. 2016, 25, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L. Invitation à la Sociologie Réflexive; Seuil: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Sobre el poder simbólico. In Intelectuales, Política y Poder; EUDEBA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Posada, L. Sobre Bourdieu, el habitus y la dominación masculina: Tres apuntes. Rev. Filos. 2017, 73, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durkheim, E. Estructura Social y Subjetividad; Ediciones Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo: Hidalgo, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ramírez, R. Technology and self-modification: Understanding technologies of the self after Foucault. J. Sci. Technol. Arts 2017, 9, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles, J.; Solano, C. El modelo estructural dialéctico de los cuidados. Una guía facilitadora de la organización, análisis y explicación de los datos en investigación cualitativa. Investig. Qual. Saúde 2016, 2, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Knowledge & Human Interest; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P.L.; Luckman, T. La Construcción Social de la Realidad; Amorrortu: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, R. The Meaning of Representation; College de France: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Laqueur, T. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.W. Gender and the Politics of History; Jenson Books Inc.: Logan, UT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Barreiro, A. La Construcción Social del Cuerpo en las Sociedades Contemporáneas; Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leye, E.; Van Eekert, N.; Shamu, S.; Esho, T.; Barrett, H. Debating medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C): Learning from (policy) experiences across countries. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siles, J. La naturaleza histórica y dialéctica de los procesos de Globalización- Glocalización y su incidencia en la cultura de los cuidados. Index Enferm. 2010, 19, 162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Alemany-Anchel, M.J.; Velasco-Laiseca, J. Género, imagen y representación del cuerpo. Index Enferm. 2018, 17, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gele, A.A.; Johansen, E.B.; Sundby, J. When female circumcision comes to the West: Attitudes toward the practice among Somali Immigrants in Oslo. BMC Public Health 2012, 27, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnsdotter, S. Birgitta Essén Cultural change after migration: Circumcision of girls in Western migrant communities. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 32, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Women Leaders | Age | Country of Origin | Time in Spain (years) | Civil Status Activity | Children | Activity Against the MGF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WL1 | 46 | Guinea Bissau | 14 | Separate | 1 girl | Active partition in associations |

| WL2 | 53 | Kenya | 22 | Separate | 3 (2 boys and 1 girl) | Active partition in associations |

| WL3 | 27 | Guinea Bissau | 15 | Single | No | Active partition in associations |

| WL4 | 38 | Mali | 12 | Married | 3 (2 boys and 1 girl) | Occasional collaborator |

| WL5 | 61 | Gambia | 44 | Divorced | 5 (3 girls and 2 boys) | Active partition in associations (President of an association against FGM) |

| WL6 | 49 | Mali | 18 | Divorced | 2 girls | Active partition in associations |

| WL7 | 38 | Guinea Bissau | 17 | Divorced | 3 (2 boys and 1 girl) | Occasional collaborator |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siles-González, J.; Gutiérrez-García, A.I.; Solano-Ruíz, C. Leadership among Women Working to Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation: The Impact of Environmental Change in Transcultural Moments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165996

Siles-González J, Gutiérrez-García AI, Solano-Ruíz C. Leadership among Women Working to Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation: The Impact of Environmental Change in Transcultural Moments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):5996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165996

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiles-González, José, Ana Isabel Gutiérrez-García, and Carmen Solano-Ruíz. 2020. "Leadership among Women Working to Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation: The Impact of Environmental Change in Transcultural Moments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 16: 5996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165996

APA StyleSiles-González, J., Gutiérrez-García, A. I., & Solano-Ruíz, C. (2020). Leadership among Women Working to Eradicate Female Genital Mutilation: The Impact of Environmental Change in Transcultural Moments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165996