Institutional Engagement Practices as Barriers to Public Health Capacity in Climate Change Policy Discourse: Lessons from the Canadian Province of Ontario

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualizing Stakeholder Engagement and Climate Change Policies

3. The Context of Ontario’s Climate Change Policy Discourse and Public Health Engagement

How have the existing institutions and governance (both processes and structures) in Ontario impacted, enabled, or constrained the inclusion, participation, deliberation, and capacity of public health stakeholders in the province’s climate change policy discourse?

4. Methods

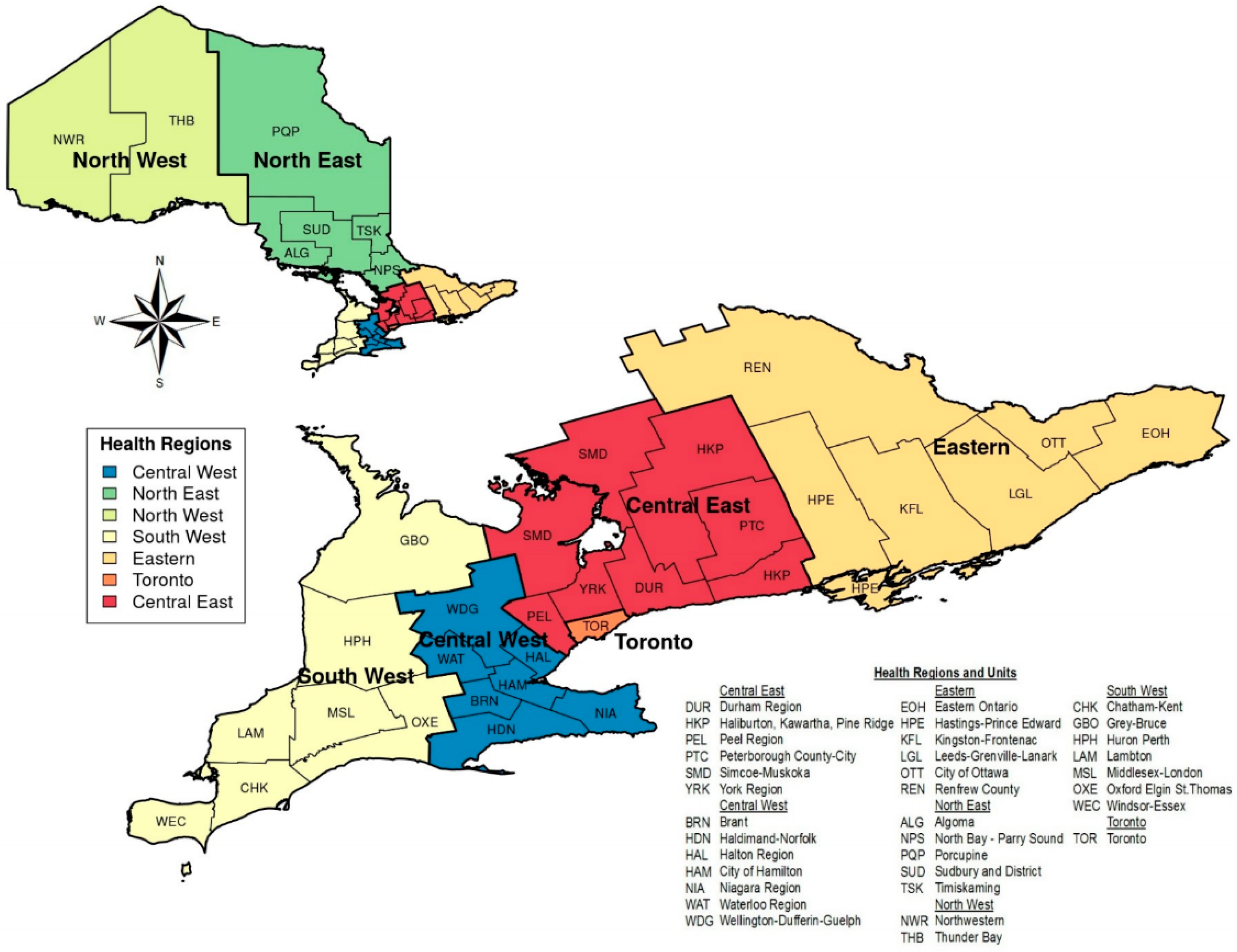

4.1. Sampling and Recruitment

4.2. Inclusion Criteria

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Participant Characteristics

5.2. Influences on Public Health Stakeholder Engagements

5.2.1. Fragmented Discursive and Communicative Interactions with Irregular and Unestablished Communication Channels

“For us, the sector is the public health sector. We also worked very closely with our key stakeholders. So, our key stakeholders would be the public health units; some of our key public health organizations like CIPHI (Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors), APHEO (Association of Public Health Epidemiologists of Ontario), ASPHIO. We also work very closely with OPHA (Ontario Public Health Association), and members from the OPHA.”(PH participant)

5.2.2. Influence of Sociopolitical Characteristics of Climate Change Governance

“I know that public health can play a role in climate change policies. But as much as I recognize that, the work that we do, and the people that we collaborate with are sometimes determined by political structures, to some degree. We really don’t have an influence on who we collaborate with in climate change policies. Our mandate, for example, and these are mandates that generally come from the Premier’s office, specifies that we work with certain ministries and sectors and so we generally make a point to either directly or indirectly connect with such organizations. So, again, it is politics. Yes, I may have an area where I would like to work with public health in our policies, but our resources and actions are tied to certain actors and not necessarily to public health. Politics basically dictate the direction.”(NPH participant)

“Those we work with are mainly determined by the MOECC (now MECP). So far, I have not received an indication. I think if you believe that public health needs to be included in (redacted) then maybe that has to come from the ministry (MECP) or even the mandate letters that give directions to the top bureaucrats.”(NPH participant)

“…back to the Ministry of Health… you weren’t finding someone there who is being the champion and leading the way and inspiring others, so this makes it hard.”(PH participant)

5.2.3. Restrictive Structures and Processes of Stakeholder Engagement

“Yeah, so whenever a policy is proposed, we are required to post it in the registry for public comment. We don’t necessarily have a roundtable discussion with many stakeholders unless they are among the ministries that we work with, especially on the various committees we have. But to say that we do have a face-to-face consultation with the public, including public health people, no! But we always receive a lot of comments from many other organizations, including public health.”(NPH participant)

“Some of the meetings I have attended barely have women in them. I think…maybe…this could be just the nature of issues being addressed because I find that many built environment areas are dealing with energy, transportation, or other infrastructure that are dominated by male, especially engineers. But it really makes you so nervous and anxious when I’m putting my points across. Are they even going to consider what I say, or I am even relevant here?”(PH participant)

5.2.4. Resources

“Because our ministry… and our applied research nature, we have been taking climate change into consideration, probably since as early as the 80s. We may have some long-term data set that we might be able to provide more of a service to public health institutions than they realize. Unfortunately, they don’t reach out to us.”(NPH participant)

5.2.5. Ideological Biases

“That is something we have come across as well. You know, sort of the question of why is public health here?”(PH participant)

“It’s pretty much the same conversation that we have been having related to public health and the built environment. You know, because really the lead ministries related to the built environment are the Municipal Affairs and Housing and Transportation and so through the (redacted) we have spent a lot and doing a lot of work on how do we engage the municipal planning sector. And now, how do we engage the transportation sector? And they say the same exact things. Like, you know, why would we invite public health? What interest would they have on a road plan? Same thing, we have talked to transportation engineers, we have talked to transportation planners about if they engage with public health and if so how or where the input would best be and … yeah, the same conversation, different topics.”(PH participant)

5.3. Effects of Interorganizational Engagements on Public Health

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide

| Overarching Themes | Questions | Possible or Additional Probes |

| Policy background | Can you please tell me a little about your position and the responsibilities you have in this post? | What roles do you play in [insert organization]? |

| Please tell me how you have addressed issues about climate change in [insert the sector/organization] policies | When did that happen? Who else was involved? How does your role relate to the broader climate change strategies in Ontario? What are some of the reasons for engaging in such policies? What are some of the accomplishments you have achieved in your engagements? | |

| Policy processes | What is the mandate of your organization in climate change? How are climate change decisions made? Are there policies that have/have not worked? What were the reasons for the successes and challenges? | Priorities and focus Policy influences Is public health integrated/relevant in the decision-making structures, and processes? Policy evaluations |

| Meaning of climate change | What does climate change mean to you? Are such definitions shared amongst the actors in the organization? | When you think about climate change what comes to mind and how does that inform the policies that you develop? |

| Collaborations | Have you worked with other institutions/sectors/ministries to support climate change actions? | Who were they? When did this happen? What was your role? How did that come about? How did you feel about your role? |

| Are you aware of any climate change action plan/document/policy that your office/organization has been a part of? If none, are there any plans for future policies or actions? OR Has your organization collaborated with other ministries/organizations to support climate change actions? OR How does your [insert organization] work with other institutions/sectors/ministries on climate change issues? | Would you elaborate on that? When did this happen? Did you have a role that you would like to elaborate on? Could you mention other sectors included in this (these) policy process(es)? | |

| Given the number of sectors that influence climate change policies, is there ever any overlap or conflicts? If yes, how are disagreements resolved? | What challenges have you experienced given the intersectoral nature of climate change policies? | |

| Have you tried to include pH professionals into your climate change strategies to minimize such conflicts? | (this question presents an opportunity for asking questions relating to consideration of public health when challenges emerge) | |

| Have you tried to integrate public into your health climate change policies? If yes, how so? If not, why not? | Has public health played any role in your climate change policy processes? | |

| Evidence | What type of evidence do you consider when developing and deliberating on climate change policies? | How are such evidence accessed? How are the needs determined? How is the evidence integrated into climate change policies? |

| Are public health evidence considered? | How are such evidence accessed? How are the needs determined? How is the evidence integrated into climate change policies? | |

| Do you utilize decision support tools? | What types are utilized; how, when, where, and why? | |

| Perception of public health inclusion Public health’s role/leadership | What is your view of health professionals advocating for the inclusion of public health the climate change frameworks? | Are climate change and public health connected? |

| Do you believe that public health has a role in leading role in climate change actions? | ||

| What is your view of health professionals advocating for a public health frame of climate change? | ||

| Do you think the inclusion of public health in the core climate change frameworks is essential for sustainable climate change actions? If yes, how so? | Could you tell me more about that? | |

| In the long-term, do you think public health has a place in the climate change discourse? | If yes, how so? If no, why not? | |

| Do you think a public health frame is relevant to your organizational policies? | ||

| Can a public health leadership be emphasized when others (such as the MOECC) are leading climate change discourse? | ||

| Has anyone ever asked your views on the inclusion of public health on climate change policy processes? If yes, how often? | If yes, what impact did this have on your policies? If not, why do you think public health has not been considered in your policy discussions? | |

| Closing | Is there anything else you would like to add to what we have covered? | |

| Can I contact you later in case I have any questions? |

Appendix B. Interview Questions Guiding Themes

Policy background

|

Climate change policies and processes

|

Meanings of climate change and public health needs (personal and professional opinions)

|

Stakeholders and collaborations

|

Evidence

|

Perspectives

|

Appendix C. Main Issues Analyzed in Textual Analysis and Discursive Practices

Thematic frames (climate change framing in Ontario)

| Genre

|

Intertextuality

| Discourse

|

Style (identificational meanings)

| Social differences

|

Social events

| Representation of social events

|

Assumptions

| Modality

|

Actional Meanings (exchanges, speech functions, and grammatical mood)

| Meaning relations

|

| Source: [34,111]. | |

Appendix D. Contexts of Collaboration

| Attribute | No. of Responses | Sample Quotes |

| Would collaborate only when public health reached out | N = 7 | “I think if public health approached us for inclusion in one of our processes for climate change, we would consider such partnerships. Maybe they just need to explain to us a little bit more of how their involvement will benefit or complement what we are currently doing.” [NPH participant] |

| Would collaborate only on known areas of public health or a public health issue is identified | N = 8 | “I believe we would collaborate with public health if what we are working on issues directly touched public health mandates… such as those related to climate change and its impact on diseases. But again, those are not the focus of our policies. So it may be hard to say that, yes, I will include public health.” [NPH participant] |

| When PH focus is identified, the issue is transferred to PH | N = 9 | “If there is a public health implication in this policy proposal, we are going to move it to the public health people. Like I think they have a public health division there.” [NPH participant] |

| Do not collaborate with PH at all | N = 10 | “No, no involvement of public health agencies.” [NPH participant] |

| Public health is responsible for initiating collaboration | N = 8 | “No, I don’t think there is like a specific topic health perspective. It is like that’s really the responsibility of the ministry of health, public health is their mandate,…so it’s up to them to ask other ministries to consider public health.” [NPH participant] |

| Acknowledge public health relevance but do not collaborate | N = 6 | “I would say I’ve been asked what the public health ramifications of some of our findings might be but to say that I’m being inclusive, or including public health, I can’t say that we do that definitively, no.” [NPH participant] |

| Do not see the role of public health in their work | N = 6 | “No, I don’t think there is like a specific … health perspective.” [NPH participant] |

| “I have not worked with public health or consulted public health in any of the policies we developed. I don’t think there was any role that public health could have played in our policies.” [NPH participant] | ||

| Public health is only a small consideration of the overall policies | N = 6 | “We deal with broad climate change issues and when you consider public health issues, it is only a small proportion of what the climate change policies target. I think at this stage in climate change policies, we can’t target every little impact that climate change poses…I mean, I don’t think we are there yet…I think that what current policies and decisions are targeting are more broadly defined.” [NPH participant] |

Appendix E. Structures for Stakeholder Identification (as Reported by the NPH Group)

| How Stakeholders are Identified | Sample Quote |

| Bureaucracy | “More specific issue is the bureaucracy itself. And ministry always has, sort of, known stakeholders. Like people or specific organizations that they have reached to before, that would typically be …. anyone who would write to the minister. Generally, there is a tradition in Ontario that people who contact the Minister might have an opportunity to talk directly to the political level about a topic. So, in theory, there are people and organizations who have the opportunity to meet with the politicians to talk about climate change, for example. And then there are also organizations with whom the administration might need informally to understand more about what actors are working on out there, and how the government policy design might leverage and work with what’s already happening. For example, on climate change information, we were very aware of not getting in the way of organization that makes it their business to translate climate change data, and instead, designing a government program that would build on the activities already taking place in municipalities and private sector.” [NPH participant] |

| Environmental registry | “In terms of structure to identify stakeholders in Ontario, it really is the Environmental Registry that is used to identify number of stakeholders and to understand the public need and the challenges and gaps that might be important when designing a new environmental policy.” [NPH participant] |

| Internalized stakeholders | “I mean some of them (stakeholders) just become internalized, and people go on” [NPH participant] |

| “At the end of the day, every ministry has their share of stakeholders who they put at the forefront.” [NPH participant] | |

| “We have those stakeholders that we have worked with on other climate change decision processes, and we turn to them when similar platforms arise.” [NPH participant] | |

| Political direction | “They [the government] would give the political level some direction, always.” [NPH participant] |

| Approach the MOHLTC | “I think if we were looking for specific public health stakeholders or health stakeholders, we would go to the Ministry of Health for their thoughts.” [NPH participant] |

| Historical contexts | “The ministry has demonstrated long-term collaborative work with partners across ministries who engage in climate change. These collaborations did not begin with climate change, but we have also engaged in other projects that impact the environment in general. And so whenever something new comes up, like climate change, for example, we have these people, from ministries, that we are already working with and who we know their expertise... I think it makes it easier that way, rather than finding new partners to work with.” [NPH participant] |

Appendix F. Impacts of Engagements on Public Health’s Capacities

| Impact | Sample Quotes | Level of Influence |

| Knowledge exchange | “[collaboration] provided us with a forum to do a lot of knowledge translation and a lot of knowledge exchange, and …. I have worked with other health units that are now in the process of doing it [V and A assessment]. So I have worked with [redacted], I have worked closely with [redacted]. Each community has to do a vulnerability assessment in their own way, but there are lessons that can be learned, and so I have met with them. I have had discussions with a number of other health units, [redacted] in [redacted]. Just this past week, I have had some discussions with [redacted] in [redacted]. So they are looking at doing vulnerability assessment similar to what we did and so, you know, lessons learned, those kinds of thing.” [PH participant] | Local |

| Learning, knowledge sharing and exchange, and skills development | “It was an enormous learning curve for me, but it was really interesting because I brought perspectives for it that perhaps we wouldn’t have thought of, and it was really interesting dialogue, and we all collectively learned a lot from each other.” [PH participant] | Local |

| “I am learning from my colleagues as much as they are learning from me, and so you know, you take the lessons learned back, and you incorporate it into the work that you are doing. So it is a lot of capacity building; it’s a lot of knowledge translation, those kinds of things.” [PH participant] | ||

| Access to resources | “One piece that we identified within our key informant interviews was the need for a regional network that could help to bring different stakeholders together to support climate change mitigation and adaptation, and that’s because most of our municipalities are quite small and they are resource-strapped, and they don’t have either the money or the knowledge to be able to start some of the climate change adaptations. And so they wanted a way that they could have a community of practice or a sharing network or a way that they could collaborate to create regional actions. So the health unit has been working to pull that group together, and it is something that we are going to be continuing to lead over the next couple of years. We are calling it a [redacted], where we have conservation authorities, school boards, municipalities, and ourselves as health unit partners working together to identify what others are doing, where there could be collaborations and partnerships and what funding opportunities could be done collaboratively. And so it was one of those pieces that everyone sort of said we need this, but no one was able or had the resources to step up and lead. And so, we were able to put those resources into that program, and we will continue to do so.” [PH participant] | Local |

| Building capacities beyond climate change needs | “So I think it is an opportunity [collaborating with others] that other health units hopefully can take up as well, and we have done it for other program areas, for social determinants of health, for healthy built environment. Public health has been engaged in community development and engagement for many years, and so I think this is just another area that public health can lead in.” [PH participant] | Local |

| Advocacy | “As well, I sat on the vulnerability assessments from [redacted], so as I mentioned—water, wastewater, infrastructure and so on—and brought forth a public health lens to those vulnerability assessments.” [PH participant] | Local |

| Strategic | “That work [that is, a vulnerability assessment that the participant did in collaboration with other stakeholders] has driven much of the work that we have done since”. [PH participant] | Local |

| Platforms for potential and future partnerships | “What that [a previous collaboration] also did was set stage for further partnership work, and we have done a couple of interesting projects with partners that perhaps we wouldn’t have worked with as closely in the past. For example, we developed a tool to look at [redacted] and brought in a social-economic lens, brought in a health protection lens. Looking at things like urban heat island. Looking at equity, all those kind of issues, … we are now doing a pilot project applying that tool in [redacted] and looking at communities that are disadvantaged for one reason or another and looking to see if we can try and impact things like the urban heat island. So there has been a lot of involvement in a lot of different projects and people have been, in my mind, very welcoming of the public health lens to the discussion. The engineers welcomed us; the planners have welcomed us. There has been learning of each other’s languages and needs, and that takes time, but certainly, there has been no hesitation, whatsoever, to have public health sitting at the table.” [PH participant] | Local |

| Inclusion of public health mandate | “[redacted] that promoted or pushed to have more information or more requirements in the public health standards related to public health action on climate change, and I do know that a lot of the health units are doing that work.” [PH participant] | Provincial and local |

| Accessing hard-to-reach communities | “We did try to engage with our First Nation and Metis communities within the region. We were unsuccessful in engaging in that for the vulnerability assessment key informant process. I think we just didn’t have the right contact. We weren’t connecting with the right people. I personally didn’t have any connections with any of our first nations partners from previous work, and like, I think we weren’t just connecting with the right people, but we have since been able to work with some of our local communities, and we are involved in some projects that are supporting adaptation planning within First Nations communities within our region, and so, that was really great, having some conversations with an individual at First Nations who was doing some climate change adaptation, and I was wanting to see what they were doing and then meeting her at other conferences, and that allowed us to build a relationship, and she then brought us into her projects that she’s doing. So that has been really great because we saw a gap in our vulnerability assessment …we didn’t have any Indigenous views throughout the vulnerability assessment…. and so, now that we have those connections, it has been great, and there has been a real collaborative approach to being able to support them when we can with our vulnerability assessment and they are using traditional ecological knowledge as well to further adaptation planning, so it has been really great to be able to start to build those relationships.” [PH participant] | Local |

| Advanced coal phase-out | “ [Redacted] appeared before the legislative committee and conservatives said, this is a waste of time, we don’t need a legislation, we have already stopped burning coal for electricity…We said that we want to be there a legislation so that anybody who tries to reverse it, it’s going to be harder to do that. And everyone was kind of like, we will never go back, and then what happened two years later? You know, you had a president [referring to U.S politics] who was now calling for burning of coal. So, I would say that was our role. So I’ll just say, we have had this tradition of speaking out about the links between the environment and health and we are going to continue to do that.” [PH participant] | Provincial |

References

- Kreuter, M.W.; De Rosa, C.; Howze, E.H.; Baldwin, G.T. Understanding Wicked Problems: A Key to Advancing Environmental Health Promotion. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, B.W. Evidence, Uncertainty, and Wicked Problems in Climate Change Decision Making in Australia. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2014, 32, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woezik, A.F.G.; Braakman-Jansen, L.M.A.; Kulyk, O.; Siemons, L.; Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C. Tackling wicked problems in infection prevention and control: A guideline for co-creation with stakeholders. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2016, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Wallace, L.; Velarde, S.J.; Wreford, A. Adaptive governance good practice: Show me the evidence! J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 222, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, B.C.; Gosnell, H.; Cosens, B.A. A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: Synthesis and future directions. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governce and social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, L.; Folke, C.; Österblom, H.; Olsson, P. Adaptive governance, ecosystem management, and natural capital. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7369–7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T. Climate Change and Global Policy regimes: Towards Institutional Legitimacy. Palgrave Macmillan. 2013. Available online: http://catalogue.library.ryerson.ca/record=b2442109 (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Savan, B.; Gore, C.; Morgan, A.J. Shifts in Environmental Governance in Canada: How are Citizen Environment Groups to Respond? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2004, 22, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maibach, E.W.; Nisbet, M.C.; Baldwin, P.; Akerlof, K.L.; Diao, G. Reframing climate change as a public health issue: An exploratory study of public reactions. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, T.; Nisbet, M.C.; Maibach, E.W.; Leiserowitz, A.A. A public health frame arouses hopeful emotions about climate change. Clim. Chang. 2012, 113, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, K.L.; Debono, R.; Berry, P.; Leiserowitz, A.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Clarke, K.-L.; Rogaeva, A.; Nisbet, M.C.; Weathers, M.R.; Maibach, E.W. Public Perceptions of Climate Change as a Human Health Risk: Surveys of the United States, Canada and Malta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 2559–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Horton, R. Tackling climate change: The greatest opportunity for global health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1798–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.; Phillips, N. Strategies of Engagement: Lessons from the Critical Examination of Collaboration and Conflict in an Interorganizational Domain. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C. Lateral Public Health: A Comprehensive Approach to Adaptation in Urban Environments; Springer: Dodrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, C.; Smith, J.A. Climate Change, Public Health, and Policy: A California Case Study. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 108, S114–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health in the Green Economy: Health Co-Benefits of Climate Change Mitigation—Transport Sector; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, K.J.; Weinthal, E. Mitigating Mistrust? Participation and Expertise in Hydraulic Fracturing Governance. Rev. Policy Res. 2016, 33, 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Evengård, B.; Sauerborn, R.; Byass, P. Connecting the Global Climate Change and Public Health Agendas. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Chambers, J.; et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: From 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet 2018, 391, 581–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Berry, H.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; et al. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. Lancet 2018, 392, 2479–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Bai, Y.; Byass, P.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Colbourn, T.; Cox, P.M.; Davies, M.; Depledge, M.; et al. The Lancet Countdown: Tracking progress on health and climate change. Lancet 2017, 389, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, S.E.; Ford, J.H.; Ford, J.H.; Araos, M.; Parker, S.; Fleury, M.D. Public Health Adaptation to Climate Change in Canadian Jurisdictions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 623–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, S.E.; Biesbroek, R.; Ford, J.H.; Ford, J.H.; Parker, S.; Fleury, M.D. Public Health Adaptation to Climate Change in OECD Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, L.; Gould, S.; Berko, J. Climate Change, Healh and Equity: Opportunities for Action; Public Health Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M.; Lee, M.; et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, A.; Blashki, G.; Bowen, K.J.; Karoly, D.J.; Wiseman, J. The Political Economy of Health Co-Benefits: Embedding Health in the Climate Change Agenda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, P.J.; Zhang, Y.; Bambrick, H.; Berry, H.L.; Linnenluecke, M.K.; Trueck, S.; Bi, P.; Boylan, S.M.; Green, D.; Guo, Y.; et al. The 2019 report of the MJA-Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: A turbulent year with mixed progress. Med. J. Aust. 2019, 211, 490–491.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.A.; Zuidema, C.; Bauman, B.; Burke, T.; Sheehan, M. Integrating Public Health into Climate Change Policy and Planning: State of Practice Update. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, N.; Watts, N. Climate Change: From Science to Practice. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M. Social Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Kohl, C.; Da Silva, N.R.; Schiemann, J.; Spök, A.; Stewart, R.; Sweet, J.B.; Wilhelm, R. A framework for stakeholder engagement during systematic reviews and maps in environmental management. Environ. Évid. 2017, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljan, L.A.; Brooks, S. Public policy in Canada: An Introduction, 7th ed.; Mills, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: North York, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney, P. Understanding Public Policy; Edward Elgar Publishing Company: Cheltenham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, W. Public Policy: An Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Policy Analysis; Edward Elgar Publishing Company: Cheltenham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Historica Canada. Public Policy. The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2019. Available online: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/public-policy (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Luís, S.; Lima, M.L.; Roseta-Palma, C.; Rodrigues, N.; Sousa, L.P.; Freitas, F.; Alves, F.L.; Lillebø, A.; Parrod, C.; Jolivet, V.; et al. Psychosocial drivers for change: Understanding and promoting stakeholder engagement in local adaptation to climate change in three European Mediterranean case studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. A Typology of Public Engagement Mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Key Element 6: Collaborate Across Sectors and Levels|Canadian Best Practices Portal—CBPP. Canadian Best Practice Portal. 2016. Available online: http://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/population-health-approach-organizing-framework/key-element-6-collaborate-sectors-levels/ (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Miller, W.; Pellen, R.M. Libraries Beyond their Institutions: Partnerships that Work; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schöttle, A.; Haghsheno, S.; Gehbauer, F. Defining Cooperation and Collaboration in the Context of Lean Construction. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Oslo, Norway, 25–27 June 2014; pp. 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Best Practice Portal: Partnerships, Collaboration and Advocacy. 2015. Available online: https://cbpp-pcpe.phac-aspc.gc.ca/resources/public-health-competencies-information-tools/partnerships-collaboration-advocacy/ (accessed on 6 August 2019).

- Gosselin, P.; Bélanger, D.; Lapaige, V.; Labbé, Y. The burgeoning field of transdisciplinary adaptation research in Quebec (1998–): A climate change-related public health narrative. J. Multidiscip. Health 2011, 4, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melillo, J.M.; Richmond, T.; Yohe, G.W. Climate change impacts in the united states: The third national climate assessment. Eval. Assess. 2014, 61, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, D.; Congreve, A. Collaborative approaches to local climate change and clean energy initiatives in the USA and England. Local Environ. 2016, 22, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, R.; Gray, B. Collaborating: Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problems, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, S.F.; Luke, D.; Schooley, M.W.; Elliott, M.B.; Herbers, S.H.; Mueller, N.B.; Bunger, A.C. Public health program capacity for sustainability: A new framework. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, J.; Fulop, N.; Gagnon, D.; Allen, P. On Being a Good Listener: Setting Priorities for Applied Health Services Research. Milbank Q. 2003, 81, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, J.; Abelson, J.; Kouyaté, B.; Lavis, J.N.; Walt, G. Why do policies change? Institutions, interests, ideas and networks in three cases of policy reform. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. The Discourses of Climate Change. In Climate Change and Global Policy Regimes; Cadmnan, T., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2013; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Moloughney, B. Community Engagement as a Public Health Approach: A Targeted Literature Review—Final Report. 2012. Available online: https://www.peelregion.ca/health/library/pdf/Community_Engagement.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2018).

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (NCCDH). A Guide to Community Engagement Frameworks for Action on the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity; National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health: Antigonish, NS, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, K.N.; Miller, E. Strengthening stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2017, 6, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2417–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.; Ford, J.H. Stakeholder engagement in adaptation interventions: An evaluation of projects in developing nations. Clim. Policy 2013, 14, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, E.J.; Betley, E.; Sigouin, A.; Gomez, A.; Toomey, A.; Cullman, G.; Malone, C.; Pekor, A.; Arengo, F.; Blair, M.; et al. Assessing the evidence for stakeholder engagement in biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 209, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, T.; Brown, C. Engagement and Participation for Health Equity. 2017. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/353066/Engagement-and-Participation-HealthEquity.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 8 July 2018).

- Chan, S.; Van Asselt, H.; Hale, T.; Abbott, K.W.; Beisheim, M.; Hoffmann, M.; Guy, B.; Höhne, N.; Hsu, A.; Pattberg, P.; et al. Reinvigorating International Climate Policy: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Nonstate Action. Glob. Policy 2015, 6, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concannon, T.W.; Fuster, M.; Saunders, T.; Patel, K.; Wong, J.B.; Leslie, L.K.; Lau, J. A Systematic Review of Stakeholder Engagement in Comparative Effectiveness and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavallee, D.C.; Williams, C.J.; Tambor, E.S.; Deverka, P.A. Stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research: How will we measure success? J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2012, 1, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.; Dowd, A.-M.; Mason, C.; Ashworth, P. A Framework for Stakeholder Engagement on Climate Adaptation National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry. 2009. Available online: http://www.csiro.au/resources/CAF-working-papers.html (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Hoffman, A.; Montgomery, R.; Aubry, W.; Tunis, S.R. How Best To Engage Patients, Doctors, And Other Stakeholders In Designing Comparative Effectiveness Studies. Health Aff. 2010, 29, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetoo, S. Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Climate Governance: The Case of the City of Turku. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Ministry of Environment Conservation and Parks. 2016 Annual Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. 2016. Available online: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en16/v1_302en16.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2017).

- Ministry of Environment, Conservation, and Parks. Ontario Introduces Legislation to End Cap and Trade Carbon Tax Era in Ontario. Newsroom. 2019. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/ene/en/2018/07/ontario-introduces-legislation-to-end-cap-and-trade-carbon-tax-era-in-ontario.html (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Premier Doug Ford Announces the End of the Cap-and-Trade Carbon Tax Era in Ontario. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2018/07/premier-doug-ford-announces-the-end-of-the-cap-and-trade-carbon-tax-era-in-ontario.html (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Bill 4, Cap and Trade Cancellation Act. 2018. Available online: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/parliament-42/session-1/bill-4 (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Annual Report 2019: Report on the Environment. 2019. Available online: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arbyyear/ar2009.html (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Ontario Ministry of Environment Conservation and Parks. Preserving and Protecting our Environment for Future Generations: A Made-in-Ontario Environment Plan. 2018. Available online: https://prod-environmental-registry.s3.amazonaws.com/2018-11/EnvironmentPlan.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Government of Ontario. Green Deal: Energy Saving for Your Home or Business. 2018. Available online: http://archive.is/EgmKX (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Ontario’s Government for the People Introduces Legislation to Repeal the Green Energy Act. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/mndmf/en/2018/09/ontarios-government-for-the-people-introduces-legislation-to-repeal-the-green-energy-act.html (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Ontario Repeals the Green Energy Act. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/mndmf/en/2018/12/ontario-scraps-the-green-energy-act.html (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Premier Doug Ford and Premier Scott Moe Pledge to Continue the Fight Against the Federal Carbon Tax. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2018/10/premier-doug-ford-and-premier-scott-moe-pledge-to-continue-the-fight-against-the-federal-carbon-tax.html (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Premier Doug Ford and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe to Work Together to Fight Carbon Tax and Encourage Interprovincial Trade. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2018/10/premier-doug-ford-and-saskatchewan-premier-scott-moe-to-work-together-to-fight-carbon-tax-and-encour.html (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Premier Doug Ford and Premier Scott Moe Agree to Fight Federal Carbon Tax. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2018/07/premier-doug-ford-and-premier-scott-moe-agree-to-fight-federal-carbon-tax.html (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Newsroom: Ontario Leads Growing Opposition to the Federal Carbon Tax. 2018. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2018/12/ontario-leads-growing-opposition-to-the-federal-carbon-tax.html (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Government of Ontario. Make No Little Plans: Ontario’s Public Health Sector Strategic Plan. Available online: http://govdocs.ourontario.ca/node/11919 (accessed on 21 March 2018).

- Wilson, K. The Complexities of Multi-level Governance in Public Health. Can. J. Public Health 2004, 95, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Region of Waterloo. Organization of Public Health in Ontario. 2019. Available online: www.regionofwaterloo.ca/ph (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Association of Local Public Health Agencies. 2018 Orientation Manual for Boards of Health. 2018. Available online: www.alphaweb.org (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Levison, M.M.; Butler, A.J.; Rebellato, S.; Armstrong, B.; Whelan, M.; Gardner, C. Development of a climate change vulnerability assessment using a public health lens to determine local health vulnerabilities: An Ontario health unit experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation. Adapting to Climate Change in Ontario: Towards the Design and Implementation of a Strategy and Action Plan. 2009. Available online: http://www.climateontario.ca/doc/publications/ExpertPanel-AdaptingInOntario.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2017).

- Ebi, K.; Anderson, V.; Berry, P.; Paterson, J.; Yusa, A.A. Ontario Climate Change and Health Toolkit. 2016. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/climate_change_toolkit/climate_change_toolkit.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ministry Reports: The Ontario Climate Change and Health Toolkit. 2016. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/climate_change_toolkit/climate_change_toolkit.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Identification, Investigation and Management of Health Hazards Protocol. 2008. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/identification_health_hazards.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The Health Hazard Prevention and Management Standard. 2010. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/healthhazard.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2018).

- Government of Ontario. Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability. 2018. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/protocols_guidelines/Ontario_Public_Health_Standards_2018_en.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2018).

- Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. Healthy Environments and Climate Change Guideline. 2018. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/protocols_guidelines/Healthy_Environments_and_Climate_Change_Guideline_2018_en.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Paterson, A.J.; Ford, J.H.; Ford, J.H.; Lesnikowski, A.; Berry, P.; Henderson, J.; Heymann, J. Adaptation to climate change in the Ontario public health sector. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponelis, S.R. Using Interpretive Qualitative Case Studies for Exploratory Research in Doctoral Studies: A Case of Information Systems Research in Small and Medium Enterprises. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2015, 10, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, J.; Coffey, B.; Cook, K.; Meiklejohn, S.; Palermo, C. A guide to policy analysis as a research method. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 34, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Ontario. Easy Map—Public Health Ontario. 2019. Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/commonly-used-products/maps/easy-map/easy-map-full (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Coyne, I. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 26, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, O.C. Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2013, 11, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Ontario. INFO-GO—Government of Ontario Employee Directory. Available online: http://www.infogo.gov.on.ca/infogo/home.html (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Government of Ontario. Environmental Registry. Available online: https://www.ebr.gov.on.ca/ERS-WEB-External/content/index2.jsp?f0=aboutTheRegistry.purpose&f1=aboutTheRegistry.purpose.value&menuIndex=0_2 (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- OPHA. CIPHI Ontario Partners–Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors. 2017. Available online: http://www.ciphi.on.ca/partners (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Nascimento, L.D.C.N.; De Souza, T.V.; Oliveira, I.C.D.S.; De Moraes, J.R.M.M.; De Aguiar, R.C.B.; Da Silva, L.F. Theoretical saturation in qualitative research: An experience report in interview with schoolchildren. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L.A. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, S.L.; Trotter, S.P. Theoretical Saturation. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J. Policy Analysis as Critique. In Oxford Handbook of Public Policy; Moran, M., Rein, M., Goodin, R.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yanow, D. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yanow, D. Interpretation in policy analysis: On methods and practice. Crit. Policy Stud. 2007, 1, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janks, H. Critical Discourse Analysis as a Research Tool. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 1997, 18, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Textual Analysis for Social Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lomas, J. Connecting research and policy. Isuma Can. J Policy Res. 2000, 1, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottner, J.; Dassen, T. Interpreting interrater reliability coefficients of the Braden scale: A discussion paper. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belur, J.; Tompson, L.; Thornton, A.; Simon, M. Interrater Reliability in Systematic Review Methodology. Sociol. Methods Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, E.F. Dialogic and Authoritative Discourse: A Constitutive Tension of Science Classroom. In École Thématique “Méthodes D’Enregistrement D’Observation et De Construction De Grilles De Collecte et D’Interpretation Des Données Vidéo Prises en Fituations de Formation; ICAR—CNRS—Université Lumière: Lyon, France, 2005; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, S.; Yazdannik, A.; Yousefy, A. Discourse analysis: A useful methodology for health-care system researches. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, P.; Mortimer, E.F.; Aguiar, O.G. The tension between authoritative and dialogic discourse: A fundamental characteristic of meaning making interactions in high school science lessons. Sci. Educ. 2006, 90, 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambe, P. Critical discourse analysis of collaborative postings on Facebook|Patient Rambe–Academia.edu. Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 28, 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, J. Vertical Discourse: The Role of the Teacher in the Transmission and Acquisition of Decontextualised Language. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 2, 496–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B. Vertical and Horizontal Discourse: An essay. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1999, 20, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-L.; Roth, W.-M. From authoritative discourse to internally persuasive discourse: Discursive evolution in teaching and learning the language of science. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2012, 9, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylett, A. Institutionalizing the urban governance of climate change adaptation: Results of an international survey. Urban Clim. 2015, 14, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddart, M.C.; Haluza-DeLay, R.; Tindall, D.B. Canadian News Media Coverage of Climate Change: Historical Trajectories, Dominant Frames, and International Comparisons. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015, 29, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deverka, P.A.; Lavallee, D.C.; Desai, P.J.; Esmail, L.C.; Ramsey, S.D.; Veenstra, D.L.; Tunis, S.R. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: Defining a framework for effective engagement. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2012, 1, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Hess, J.; Luber, G.; Malilay, J.; McGeehin, M. Climate Change: The Public Health Response. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomas, J.; Culyer, T.; McCutcheon, C.; McAuley, L.; Law, S. Conceptualizing and Combining Evidence for Health System Guidance: Final Report; Canadian Health Services Research Foundation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2005; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Human Health in a Changing Climate: A Canadian Assessment of Vulnerabilities and Adaptive Capacity. 2008. Available online: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2008/hc-sc/H128-1-08-528E.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2016).

- World Health Organization. Promoting Health While Mitigating Climate Change. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/hia/green_economy/en/ (accessed on 3 September 2019).

- Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Corvalán, C.; Neira, M. Global climate change: Implications for international public health policy. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemm, J. Health impact assessment: A tool for healthy public policy. Health Promot. Int. 2001, 16, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellstead, A.; Stedman, R. Mainstreaming and Beyond: Policy Capacity and Climate Change Decision-Making. Mich. J. Sustain. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, J.S.; Jeggo, M. The One Health Approach-Why Is It So Important? Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinsstag, J.; Crump, L.; Schelling, E.; Hattendorf, J.; Maidane, Y.O.; Ali, K.O.; Muhummed, A.; Umer, A.A.; Aliyi, F.; Nooh, F.; et al. Climate change and One Health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.; Hahn, M.B. Climate Change and Human Health: A One Health Approach. Inducible Lymphoid Organs 2012, 366, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, P.; Weller, P. Policy Advice and a Central Agency: The Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Aust. J. Polit. Sci. 2012, 47, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliba, C.; Gajda, R. “Communities of Practice” as an Analytical Construct: Implications for Theory and Practice. Int. J. Public Adm. 2009, 32, 97–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, B.R.; Swerissen, H.; Duckett, S. Four approaches to capacity building in health: Consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralle, S.; Boscarino, J. Framing Trade-offs: The Politics of Nuclear Power and Wind Energy in the Age of Global Climate Changer opr_500. 2011. Available online: https://journals-scholarsportal-info.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/pdf/1541132x/v28i0004/323_fttpontaogcc.xml (accessed on 19 September 2018).

- Cairney, P. The Role of Ideas. In Understanding Public Policy: Theories and Issues; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2012; pp. 220–243. [Google Scholar]

- Leeper, T.; Slothuus, R. Deliberation and Framing. In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Health Message Framing Effects on Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-analytic Review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 43, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valles, S.A. Bioethics and the Framing of Climate Change’s Health Risks. Bioethics 2014, 29, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.S.; Hultquist, A.; Romsdahl, R.J. An Examination of Local Climate Change Policies in the Great Plains. Rev. Policy Res. 2014, 31, 529–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romsdahl, R.J.; Blue, G.; Kirilenko, A. Action on climate change requires deliberative framing at local governance level. Clim. Chang. 2018, 149, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Betsill, M.M. Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environ. Polit. 2013, 22, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickards, L.; Wiseman, J.; Kashima, Y. Barriers to effective climate change mitigation: The case of senior government and business decision makers. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, J. Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few, R.; Brown, K.; Tompkins, E.L. Public participation and climate change adaptation: Avoiding the illusion of inclusion. Clim. Policy 2007, 7, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francisco, J.; Boelens, R. Payment for Environmental Services and Power in the Chamachán Watershed, Ecuador. Hum. Organ. 2014, 73, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaim, B. Who are We to Care? Exploring the Relationship between Participation, Knowledge and Power in Health System. 2013. Available online: www.copasah.net (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Gaventa, J.; Martorano, B. Inequality, Power and Participation—Revisiting the Links. IDS Bull. 2016, 47, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, L. Power and Participation: An Examination of the Dynamics of Mental Health Service-User Involvement in Ireland. Stud. Soc. Justice 2012, 6, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, P.; Kamanzi, A. Power analysis: A study of participation at the local level in Tanzania. ASC Working Paper 105. 2012. Available online: www.ascleiden.nl (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. Support to Civil Society Engagement in Policy Dialogue. 2013. Available online: www.danida-publikationer.dk (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Whaley, L.; Weatherhead, E.K. Power-sharing in the english lowlands? The political economy of farmer participation and cooperation in water governance. Water Altern. 2015, 8, 820–843. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J. Power Pack: Understanding Power for Social Change. 2011. Available online: www.powercube.net/analyse-power/levels-of-power/ (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- Lawrence, T.B. Power, Institutions and Organizations. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 170–197. [Google Scholar]

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada. Gender-based Analysis Plus in Impact Assessment (Interim Guidance). 2019. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/practitioners-guide-impact-assessment-act/gender-based-analysis-plus.html (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Council of Europe. Achieving Gender Mainstreaming in All Policies and Measures. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168064379a (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Government of Canada. Mainstreaming of a Gender Perspective. 2017. Available online: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/funding-financement/mainstream-integration.aspx?lang=eng (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Kelehera, H. Policy scorecard for gender mainstreaming: Gender equity in health policy. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2013, 37, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatro, M. Mainstreaming Gender: Shift from Advocacy to Policy. Vision: J. Bus. Perspect. 2014, 18, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, L.J. Gender Matters in Global Politics: A Feminist Introduction to International Relations; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Toolkit for Mainstreaming and Implementing Gender Equality: Implementing the 2015 OECD Recommendation on Gender Equality in Public Life. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/toolkit-for-mainstreaming-and-implementing-gender-equality.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2020).

| Office of the Premier (OP) |

|---|

Ministry of:

|

| Participation | NPH | PH |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants solicited | 84 | 34 |

| Total response received | 71 | 18 |

| Declined to participate: | ||

| Did not see the role of public health in their work | 46 | - |

| Lack of role or mandate on climate change | - | 1 |

| Interviewed and retained (includes four referrals from NPH and three from PH groups) | 13 | 11 |

| Accepted to participate but not interviewed (theoretical saturation) | 5 | 6 |

| No reasons provided for declining participation | 7 | - |

| Features | Definition | Emerging Influences on Public Health Stakeholder Inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Fragmented discursive and communicative interactions | Strategies and approaches for facilitating discussions and communication between PH and NPH sector |

|

| Sociopolitical characteristics of climate change governance | Social and political environments or group characteristics that support or negate collaboration with public health agencies |

|

| Restrictive structures and processes | Formal institutional structure and processes for participation and deliberation |

|

| Ideological biases | Views of whether public health is a relevant stakeholder |

|

| Resource constraints | Money, expertise, and information for advancing public health’s capacity in the discourse. |

|

| Collaborated with | NPH (n = 13) | PH (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Mandated ministries | 13 * | 4 ** |

| Non-mandated ministries (excluding MOHLTC) | 3 | 0 |

| MOHLTC | 2 | 6 |

| PHUs | 0 | 9 |

| Federal government | 3 | 8 |

| Municipal government | 2 | 7 |

| Communities | 0 | 4 |

| Non-governmental organizations | 3 | 5 |

| Health agencies (other than PHU) | 0 | 6 |

| Academia | 2 | 4 |

| Corporations | 11 | 0 |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awuor, L.; Meldrum, R.; Liberda, E.N. Institutional Engagement Practices as Barriers to Public Health Capacity in Climate Change Policy Discourse: Lessons from the Canadian Province of Ontario. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176338

Awuor L, Meldrum R, Liberda EN. Institutional Engagement Practices as Barriers to Public Health Capacity in Climate Change Policy Discourse: Lessons from the Canadian Province of Ontario. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(17):6338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176338

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwuor, Luckrezia, Richard Meldrum, and Eric N. Liberda. 2020. "Institutional Engagement Practices as Barriers to Public Health Capacity in Climate Change Policy Discourse: Lessons from the Canadian Province of Ontario" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 17: 6338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176338

APA StyleAwuor, L., Meldrum, R., & Liberda, E. N. (2020). Institutional Engagement Practices as Barriers to Public Health Capacity in Climate Change Policy Discourse: Lessons from the Canadian Province of Ontario. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176338