Do Targeted User Fee Exemptions Reach the Ultra-Poor and Increase their Healthcare Utilisation? A Panel Study from Burkina Faso

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

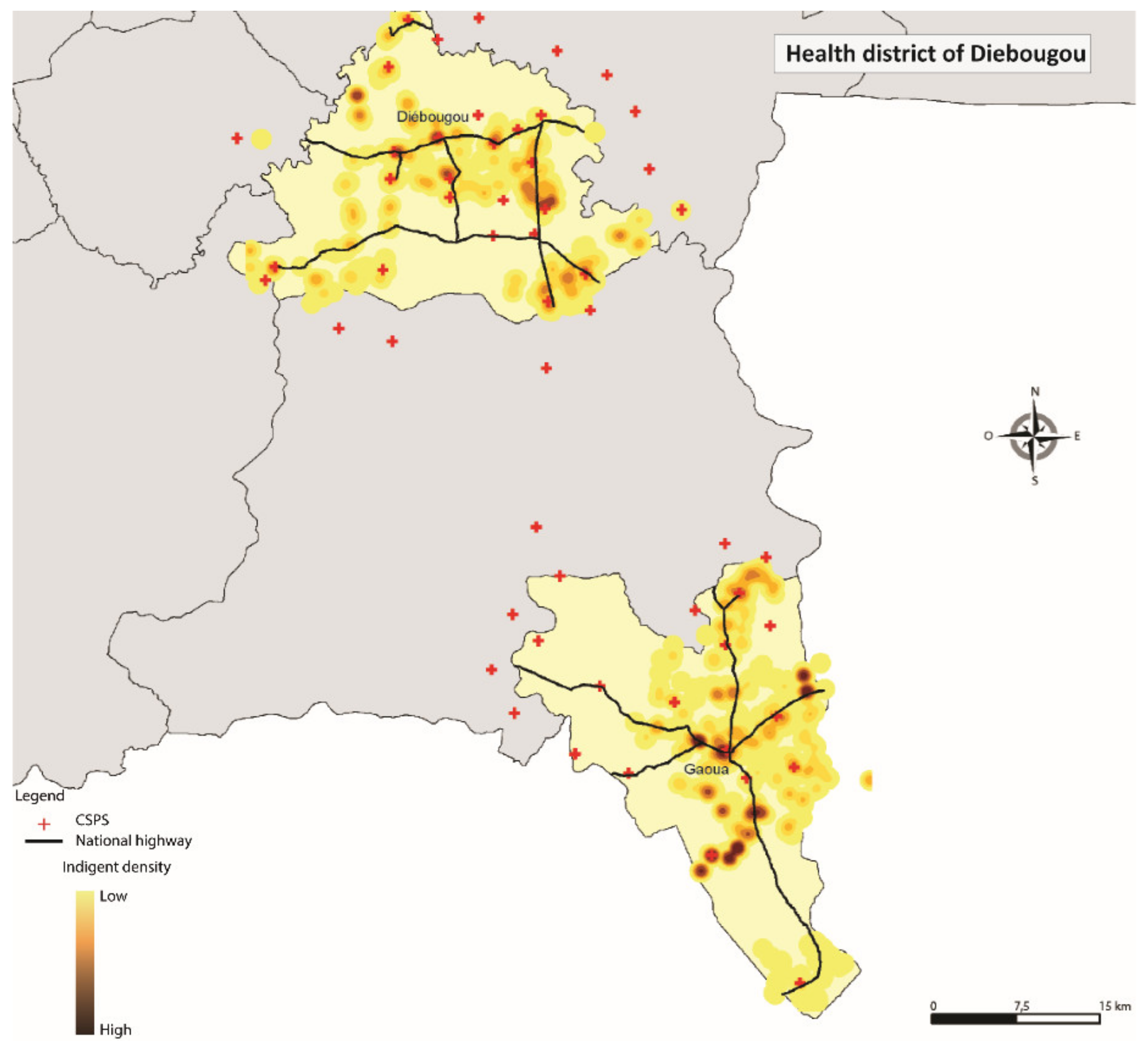

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Variables and their Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.2. Results from the Regression Model on User Fee Exemption Card Possession (Model 1)

3.3. Regression Model on Service Use (Conditional upon Reporting Ill) (Model 2)

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of Intervention Design and Implementation Failures

4.2. Equity to Sccess to Healthcare is in the Eye of the Beholder

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Acronyms

| African Maternal and Child Health Innovation Initiative | ACMHI |

| Antenatal care | ANC |

| Community-based targeting | CBT |

| Difference in differences model | DID model |

| Franc CFA | FCFA |

| Gross Domestic Product | GDP |

| International Development Research Centre | IDRC |

| Nongovernmental organisation | NGO |

| Open Data Kit software | ODK software |

| Performance-based financing | PBF |

| Primary health care centres | CSPS |

| Sustainable Development Goal | SDG |

| Universal Health Coverage | UHC |

| US-Dollar | USD |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1.—Reimbursement Procedure within PBF Context

Appendix A.2

| No | Indicator | Basic Purchase Price 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Number of new patients age 5 or older in curative consultation | 100 |

| 1b | Number of new patients age 5 or older in curative consultation—moderate subsidy for ultra-poor patient | 400 |

| 1c | Number of new patients age 5 or older in curative consultation – high subsidy for ultra-poor patient | 600 |

| 2a | Number of new patients under the age of 5 in curative consultation | 150 |

| 2b | Number of new patients under the age of 5 in curative consultation—moderate subsidy for ultra-poor patient | 500 |

| 2c | Number of new patients under the age of 5 in curative consultation—high subsidy for ultra-poor patient | 700 |

| 3a | Number of days of hospitalisation | 250 |

| 3b | Number of days of hospitalisation—moderate subsidy for ultra-poor patient | 700 |

| 3c | Number of days of hospitalisation—high subsidy for ultra-poor patient | 1100 |

| 4 | Number of counter-references received | 1010 |

| 5 | Number of children fully vaccinated | 300 |

| 6 | Number of pregnant women who have received two or more doses of tetanus vaccine | 250 |

| 7 | Number of pregnant women (new and repeat visits) in antenatal care consultation | 400 |

| 8 | Number of women in postnatal consultation (6–8 days and 6–8 weeks post-delivery) | 500 |

| 9 | Number of deliveries performed | 1510 |

| 10 | Number of women (new and repeat visits) in family planning consultation using oral or injectable contraceptives | 605 |

| 11 | Number of women (new and repeat visits) in family planning consultation using long-term methods (IUD or implant) | 1210 |

| 12 | Number of new patients aged 0–11 months in growth monitoring consultation | 100 |

| 13 | Number of patients aged 12–23 months in growth monitoring consultation | 250 |

| 14 | Number of children aged 6–59 months treated for moderate acute malnutrition | 300 |

| 15 | Number of children aged 6–59 months treated for severe acute malnutrition without complications (SAM) | 600 |

| 16 | Number of home visits affected | 3000 |

| 17 | Number of clients having benefitted from voluntary HIV testing and counselling (excluding pregnant women) tested in the context of PMTCT) | 500 |

| 18 | Number of pregnant women having benefitted from voluntary HIV testing and counselling in the context of PMTCT | 500 |

| 19 | Number of HIV-positive mothers having benefitted from complete prophylactic anti-retroviral treatment | 2500 |

| 20 | Number of newborns to HIV-positive mothers treated | 3000 |

| 21 | Number of people living with HIV under antiretroviral treatment | 1000 |

| 22 | Number of pulmonary tuberculosis cases (new and relapse) detected | 6000 |

| 23 | Number of tuberculosis cases (all types) treated and declared cured or treatment terminated | 8500 |

Appendix A.3

| No | Indicator | Basic Purchase Price |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Number of outpatient visits age 5 years or older | 220 |

| 1b | Number of outpatient visits age 5 years or older—ultra-poor patient | 675 |

| 2a | Number of outpatient visits sick children age 29 days to 59 months | 670 |

| 2b | Number of outpatient visits sick children age 29 days to 59 months—ultra-poor patient | 1350 |

| 3 | Number of neonatal emergencies | 2100 |

| 4 | Number of counter references carried out | 900 |

| 5a | Number of days of hospitalisation | 340 |

| 5b | Number of days of hospitalisation—ultra-poor patient | 4480 |

| 6a | Number of major surgeries (hernia, peritonitis, appendicitis, occlusion, other laparotomies, hydrocele, USG, open fracture trimming) performed | 14,500 |

| 6b | Number of major surgeries (hernia, peritonitis, appendicitis, occlusion, other laparotomies, hydrocele, GEU, open fracture trimming) performed—ultra-poor patient | 33,500 |

| 7 | Number of eutocic deliveries completed | 3250 |

| 8 | Number of caesarean sections performed | 6500 |

| 9 | Number of obstructed deliveries performed (Caesarean section excluded) | 5000 |

| 10 | Number of pregnant women (new and old registered) seen in prenatal consultation | 325 |

| 11 | Number of postnatal consultations performed | 900 |

| 12 | Number of women supported for abortion | 3250 |

| 13 | Number of children 0–59 months cared for severe acute malnutrition with complication | 10,000 |

| 14 | Number of people who have been voluntarily screened for HIV infection (excluding women screened for PTME) | 675 |

| 15 | Number of pregnant women screened for HIV infection in PMTCT | 675 |

| 16 | Number of HIV+ pregnant women put on prophylactic ARV protocol | 1100 |

| 17 | Number of new-borns of HIV+ women being cared for | 1100 |

| 18 | Number of new cases of HIV-infected | 2250 |

| 19 | Number of PvVIH under ARV monitored | 11,000 |

| 20 | Number of TPM+ cases detected during the month | 11,000 |

| 21 | Number of tuberculosis cases (any form) treated and declared cured or treatment completed | 22,500 |

| 22 | Number of women (old and new) seen during the month in consultation with FP and users of oral contraceptives or injectables | 1750 |

| 23 | Number of women (old and new) seen during the month in consultation with FP and users of long-term methods (IUD and implant) | 3250 |

| 24 | Number of users (old and new) seen during the month in consultation with FP and CCV users (tubal ligation and vasectomy) | 11,000 |

Appendix A.4.—Equation Model 1

Appendix A.5.—Equation Model 2

References

- Ministère de l’Action Sociale et de la Sécurité Nationale du Burkina Faso MASSN. Synthèse des résultats du comité de réflexion sur l’indigence; Government of Burkina Faso: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2010.

- Ridde, V.; Yaméogo, P. How Burkina Faso used evidence in deciding to launch its policy of free healthcare for children under five and women in 2016. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD); Ministère de l’Économie et des Finances. Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples (EDSBF-MICS IV). Burkina Faso 2010; Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie (INSD): Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2010.

- Ministry of Health Burkina Faso. La santé d’après les enquêtes statistiques nationales. Une synthèse des résultats disponibles depuis l’indépendance du Burkina Faso; Ministry of Health: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2010.

- WHO Global Health Expenditure Database. Burkina Faso. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nha/database (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- Hatt, L.E.; Makinen, M.; Madhavan, S.; Conlon, C.M. Effects of User Fee Exemptions on the Provision and Use of Maternal Health Services: A Review of Literature. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2013, 31, S67–S80. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, B.; Price, N. Improving access for the poorest to public sector health services: Insights from Kirivong Operational Health District in Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2006, 21, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, W.; Van Damme, W.; Van Pelt, M.; Por, I.; Kimvan, H.; Meessen, B. Access to health care for all? User fees plus a Health Equity Fund in Sotnikum, Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2004, 19, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, B.; Price, N.L.; Oeun, S. Do exemptions from user fees mean free access to health services? A case study from a rural Cambodian hospital. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2007, 12, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottin, R. Free Health Care for the Poor: A Good Way to Achieve Universal Health Coverage? Evidence from Morocco; Working Papers; DIAL (Développement, Institutions et Mondialisation): Paris-Dauphine, Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Flink, I.J.; Ziebe, R.; Vagaï, D.; van de Looij, F.; van ‘T Riet, H.; Houweling, T.A. Targeting the poorest in a performance-based financing programme in northern Cameroon. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Zombré, D.; Ridde, V.; De Allegri, M. The impact of reducing and eliminating user fees on facility-based delivery: A controlled interrupted time series in Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridde, V.; Haddad, S.; Heinmüller, R. Improving equity by removing healthcare fees for children in Burkina Faso. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zombré, D.; De Allegri, M.; Ridde, V. Immediate and sustained effects of user fee exemption on healthcare utilization among children under five in Burkina Faso: A controlled interrupted time-series analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 179, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchessi, N.; Ridde, V.; Zunzunegui, M.-V. User fees exemptions alone are not enough to increase indigent use of healthcare services. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Burkina Faso Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie du Burkina Faso. Table 06.04: Evolution of the consultation rate by sex and place of residence (in%) 1994 - 2007. Available online: http://www.insd.bf/n/index.php/indicateurs?id=88 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Ridde, V. From institutionalization of user fees to their abolition in West Africa: A story of pilot projects and public policies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridde, V.; Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M.; Souares, A.; Lohmann, J.; Zombré, D.; Koulidiati, J.L.; Yaogo, M.; Hien, H.; Hunt, M.; Zongo, S. Protocol for the process evaluation of interventions combining performance-based financing with health equity in Burkina Faso. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M.; Gali-Gali, I.A.; De Allegri, M.; Ridde, V. The unintended consequences of community verifications for performance-based financing in Burkina Faso. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 191, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Allegri, M.; Lohmann, J.; Souares, A.; Schleicher, M.; Hamadou, S.; Hien, H.; Haidara, O.D.; Robyn, P.J. Responding to Policy Makers’ Evaluation Needs: Combining Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Approaches to Estimate the Impact of Performance Based Financing in Burkina Faso. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Allegri, M.; Lohmann, J.; Hillebrecht, M. Results-based financing for health impact evaluation in Burkina Faso. Results report. Available online: https://www.rbfhealth.org/sites/rbf/files/documents/Burkina-Faso-Impact-Evaluation-Results-Report.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Ridde, V. Fees-for-services, cost recovery, and equity in a district of Burkina Faso operating the Bamako Initiative. Bull. World Health Organ. 2003, 81, 532–538. [Google Scholar]

- Beaugé, Y.; Koulidiati, J.-L.; Ridde, V.; Robyn, P.J.; De Allegri, M. How much does community-based targeting of the ultra-poor in the health sector cost? Novel evidence from Burkina Faso. Health Econ. Rev. 2018, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.V.; Dizon, F.F. The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Burkina Faso Plan National de Développement Économique et Social. Available online: http://presimetre.bf/document/PNDES.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Ouédraogo, S.; Ridde, V.; Atchessi, N.; Souares, A.; Koulidiati, J.-L.; Stoeffler, Q.; Zunzunegui, M.-V. Characterisation of the rural indigent population in Burkina Faso: A screening tool for setting priority healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeon-Gagné, É.; Hassan, G.; Yaogo, M.; Ridde, V. An exploratory study assessing psychological distress of indigents in Burkina Faso: A step forward in understanding mental health needs in West Africa. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atchessi, N.; Ridde, V.; Zunzunégui, M.-V. Is the process for selecting indigents to receive free care in Burkina Faso equitable? BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buor, D. Determinants of utilisation of health services by women in rural and urban areas in Ghana. GeoJournal 2004, 61, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, J.A. Utilization of health care services in rural and urban areas: A determinant factor in planning and managing health care delivery systems. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Develay, A.; Sauerborn, R.; Diesfeld, H.J. Utilization of health care in an African urban area: Results from a household survey in Ouagadougou, Burkina-Faso. Soc. Sci. Med. 1996, 43, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certo, S.T.; Busenbark, J.R.; Woo, H.; Semadeni, M. Sample selection bias and Heckman models in strategic management research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2639–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achen, C.H. The Statistical Analysis of Quasi-Experiments; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-520-04723-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A.; Fairbrother, M.; Jones, K. Fixed and random effects models: Making an informed choice. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 1051–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, A.; Jones, K. Explaining Fixed Effects: Random Effects Modeling of Time-Series Cross-Sectional and Panel Data. Political Sci. Res. Methods 2015, 3, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talen, E. Neighborhoods as Service Providers: A Methodology for Evaluating Pedestrian Access. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2016, 30, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banos, A.; Huguenin-Richard, F. Spatial distribution of road accidents in the vicinity of point sources: Application to child pedestrian accidents. Geogr. Med. 2000, 8, 54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, M.; Barroy, H.; Palmer, N. Assessing the effects of removing user fees in Zambia and Niger. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2012, 17, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garchitorena, A.; Miller, A.C.; Cordier, L.F.; Ramananjato, R.; Rabeza, V.R.; Murray, M.; Cripps, A.; Hall, L.; Farmer, P.; Rich, M.; et al. In Madagascar, Use Of Health Care Services Increased When Fees Were Removed: Lessons For Universal Health Coverage. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.; Ir, P.; Men, C.R.; O’Donnell, O.; van Doorslaer, E. Financial protection of patients through compensation of providers: The impact of Health Equity Funds in Cambodia. J. Health Econ. 2013, 32, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdu, Z.; Mohammed, Z.; Bashier, I.; Eriksson, B. The impact of user fee exemption on service utilization and treatment seeking behaviour: The case of malaria in Sudan. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2004, 19, S95–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lépine, A.; Lagarde, M.; Nestour, A.L. How effective and fair is user fee removal? Evidence from Zambia using a pooled synthetic control. Health Economics 2018, 27, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fritsche, G.B.; Soeters, R.; Meessen, B. Performance-Based Financing Toolkit; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 1-4648-0128-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Santé Burkina Faso. Guide de Mise en Oeuvre du Financement basé sur les Résultats dans le Secteur de la Santé; Government of Burkina Faso: Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2013.

- Kuunibe, N.; Lohmann, J.; Schleicher, M.; Koulidiati, J.; Robyn, P.J.; Zigani, Z.; Sanon, A.; De Allegri, M. Factors associated with misreporting in performance-based financing in Burkina Faso: Implications for risk-based verification. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, 1217–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegri, M.D.; Bertone, M.P.; McMahon, S.; Chare, I.M.; Robyn, P.J. Unraveling PBF effects beyond impact evaluation: Results from a qualitative study in Cameroon. BMJ Global Health 2018, 3, e000693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridde, V.; Gautier, L.; Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M.; Sieleunou, I.; Paul, E. Performance-based Financing in Africa: Time to Test Measures for Equity. Int. J. Health Serv. 2018, 48, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannes, L.; Meessen, B.; Soucat, A.; Basinga, P. Can performance-based financing help reaching the poor with maternal and child health services? The experience of rural Rwanda. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2016, 31, 309–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwase, T.; Lohmann, J.; Hamadou, S.; Brenner, S.; Somda, S.M.A.; Hien, H.; Hillebrecht, M.; De Allegri, M. Can Combining Performance-Based Financing With Equity Measures Result in Greater Equity in Utilization of Maternal Care Services? Evidence From Burkina Faso. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyaruka, P.; Robberstad, B.; Torsvik, G.; Borghi, J. Who benefits from increased service utilisation? Examining the distributional effects of payment for performance in Tanzania. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiede, M.; Koltermann, K. Access to Health Services–Analyzing non-Financial Barriers in Ghana, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Vietnam Using Household Survey Data: A Review of the Literature; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 61, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robert, E.; Samb, O.M.; Marchal, B.; Ridde, V. Building a middle-range theory of free public healthcare seeking in sub-Saharan Africa: A realist review. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aboagye, D.-C.; South, J.; Khan, H. Understanding qualitative and community indicators of poverty for national health insurance scheme exemptions in Ghana. Illness Crisis Loss 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nanda, P. Gender Dimensions of User Fees: Implications for Women’s Utilization of Health Care. Reprod. Health Matters 2002, 10, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samb, O.M.; Ridde, V. The impact of free healthcare on women’s capability: A qualitative study in rural Burkina Faso. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 197, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, K.J.; Valverde, P.A.; Ustjanauskas, A.E.; Calhoun, E.A.; Risendal, B.C. What are patient navigators doing, for whom, and where? A national survey evaluating the types of services provided by patient navigators. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 101, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeps, A.; Lietz, H.; Sié, A.; Savadogo, G.; De Allegri, M.; Müller, O.; Sauerborn, R.; Becher, H.; Souares, A. Health insurance and child mortality in rural Burkina Faso. Glob Health Action 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridde, V.; Yaogo, M.; Zongo, S.; Somé, P.-A.; Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M. Twelve months of implementation of health care performance-based financing in Burkina Faso: A qualitative multiple case study. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2018, 33, e153–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.; Davis, A.P.; Roos, J.M.; French, M.T. Limitations of Fixed-Effects Models for Panel Data. Sociol. Perspect. 2019, 63, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| District. | Population | Selected Ultra-Poor | Percentage of Selected Ultra-Poor (%) | Month Exemption Card Received by the District |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diébougou | 69,062 | 6034 | 9 | February 2016 |

| Gourcy | 132,280 | 5879 | 4 | June 2016 |

| Kaya | 554,117 | 22,889 | 4 | November 2015 |

| Ouargaye | 277,082 | 16,465 | 6 | December 2015 |

| Tenkodogo | 216,190 | 18,769 | 9 | December 2015 |

| Kongussi | 343,434 | 6076 | 2 | November 2015 |

| Ouahigouya | 114,294 | 19,937 | 17 | June 2016 |

| Batie | 39,330 | 6560 | 17 | February 2016 |

| Variables | Measurement | Hypothesised Direction of the Coefficient Model 1 | Hypothesised Direction of the Coefficient Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | |||

| Model 1: Possession of user fee exemption card | 0 = No | ||

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Model 2: Utilisation of healthcare services | 0 = No | ||

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Age (continuous) | 18–98 (years) | + | + |

| Sex | 0 = Male | ||

| 1 = Female | |||

| Marital status | 0 = All else | + | + |

| 1 = Married | |||

| Status in the household | 0 = No | + | + |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Household size (continuous) | 1–12 (member) | + | + |

| Enabling factors | |||

| Possession of user fee exemption card | 0 = No | NA | + |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Education | 0 = No | + | + |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Basic literacy | 0 = No | + | + |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Distance to the nearest healthcare centre | 0 ≤ 5 km | - | - |

| 1 ≥ 5 km | |||

| Need factors | |||

| Health status | 0 = All else | +- | - |

| 1 = Good | |||

| Disability | 0 = No | +- | +- |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| Health district | 1 = Kaya | +- | +- |

| 2 = Ouargaye | |||

| 3 = Diebougou | |||

| 4 = Gourcy | |||

| Time | 0 = 2015 | + | + |

| 1 = 2017 | |||

| Variables | 2015 (N = 1652) | 2017 (N = 1260) | Chi2 and t-Test | KS-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % | p-value | D-value | p-value | |

| Illness reporting | ||||||||

| No | 484 | 29.30 | 469 | 37.22 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 | |

| Yes | 1168 | 70.70 | 791 | 62.78 | ||||

| Health service utilisation | ||||||||

| No | 418 | 35.79 | 317 | 40.08 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.00 | |

| Yes | 750 | 64.21 | 474 | 59.92 | ||||

| Predisposing factors | ||||||||

| Age | 55.13 (mean) | 16.96 (SD) | 57.22 (mean) | 16.95 (SD) | 0.00 (t-test) | 0.10 | 0.00 | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 535 | 32.38 | 403 | 31.98 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| Female | 1117 | 67.62 | 857 | 68.02 | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| All else | 678 | 41.04 | 491 | 38.97 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.92 | |

| Married | 974 | 58.96 | 769 | 61.03 | ||||

| Household head | ||||||||

| No | 945 | 57.20 | 711 | 56.43 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 707 | 42.80 | 549 | 43.57 | ||||

| Household size | 1.61 (mean) | 1.58 (SD) | 2.47 (mean) | 1.97 (SD) | 0.00 (t-test) | 0.20 | 0.00 | |

| Enabling factors | ||||||||

| Exemption card possession | ||||||||

| No | 1652 | 100.00 | 306 | 24.29 | NA 1 | 0.76 | 0.00 | |

| Yes | 0 | 0.00 | 954 | 75.51 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| No | 1566 | 94.79 | 1187 | 94.21 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 86 | 5.21 | 73 | 5.79 | ||||

| Basic literacy | ||||||||

| No | 1548 | 93.70 | 1187 | 94.21 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 104 | 6.30 | 73 | 5.79 | ||||

| Distance to the nearest healthcare centre | ||||||||

| < 5 km | 1253 | 75.85 | 940 | 74.60 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |

| > 5 km | 399 | 24.15 | 320 | 25.40 | ||||

| Need factors | ||||||||

| Health status | ||||||||

| All else | 1330 | 80.51 | 964 | 76.51 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.20 | |

| Good | 322 | 19.49 | 296 | 23.49 | ||||

| Disability | ||||||||

| No | 1263 | 76.45 | 992 | 78.73 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.85 | |

| Yes | 389 | 23.55 | 268 | 21.27 | ||||

| Additional variables | ||||||||

| Health District | ||||||||

| Kaya (1) | 400 | 24.21 | 283 | 22.46 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.98 | |

| Ouargaye (2) | 423 | 25.61 | 354 | 28.10 | ||||

| Diebougou(3) | 548 | 33.17 | 412 | 32.70 | ||||

| Gourcy (4) | 281 | 17.01 | 211 | 16.75 | ||||

| Time | ||||||||

| 2015 | 1652 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2017 | 0 | 0.00 | 1260 | 100.00 | ||||

| Variable | Regression Coefficient (β) | Std Error | p-Value | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | ||||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.98 | −0.01 0.01 |

| Sex | −0.19 | 0.19 | 0.31 | −0.56 0.18 |

| Marital status | −0.07 | 0.17 | 0.69 | −0.39 0.26 |

| Status in the household | −0.23 | 0.17 | 0.18 | −0.57 0.10 |

| Household size | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 0.14 |

| Enabling factors | ||||

| Education | −0.14 | 0.38 | 0.72 | −0.88 0.61 |

| Basic literacy | −0.77 | 0.37 | 0.03 | −1.49 −0.06 |

| Distance to the nearest healthcare centre | −0.38 | 0.15 | 0.02 | −0.68 −0.07 |

| Need factors | ||||

| Perceived health | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.19 | −0.11 0.56 |

| Disability | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.81 | −0.32 0.41 |

| Health district (Kaya reference) | ||||

| Ouargaye | −0.09 | 0.18 | 0.59 | −0.44 0.25 |

| Diebougou | 1.31 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.09 1.70 |

| Gourcy | 1.75 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 1.20 2.31 |

| _cons | 0.81 | 0.42 | 0.06 | −0.02 1.65 |

| Variable | Regression Coefficient (β) | Std Error | p-Value | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing factors | ||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.02 −0.01 |

| Sex | −0.31 | 0.15 | 0.04 | −0.61 −0.01 |

| Marital status | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.17 | −0.07 0.42 |

| Status in the household | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.16 0.68 |

| Household size | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 0.14 |

| Enabling factors | ||||

| Possession of user fee exemption card | −0.07 | 0.20 | 0.73 | −0.45 0.32 |

| Education | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.20 | −0.24 1.14 |

| Basic literacy | −0.25 | 0.1 | 0.42 | −0.85 0.35 |

| Distance to the nearest healthcare centre | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.97 | −0.25 0.26 |

| Need factors | ||||

| Perceived health | −0.56 | 0.18 | 0.00 | −0.92 −0.203 |

| Disability | −0.37 | 0.13 | 0.00 | −0.63 −0.121 |

| Health district (Kaya reference) | ||||

| Ouargaye | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.60 1.30 |

| Diebougou | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.38 | −0.17 0.45 |

| Gourcy | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.58 | −0.25 0.45 |

| Time | −0.26 | 0.18 | 0.16 | −0.62 0.10 |

| _cons | 1.12 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.45 1.79 |

| /lnsig2u | −0.57 | 0.50 | −1.54 0.41 | |

| sigma_u | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.46 1.23 | |

| rho | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.06 0.31 | |

| LR test of rho = 0: chibar2(01) | 5.93 | |||

| Prob >= chibar2 | 0.01 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beaugé, Y.; De Allegri, M.; Ouédraogo, S.; Bonnet, E.; Kuunibe, N.; Ridde, V. Do Targeted User Fee Exemptions Reach the Ultra-Poor and Increase their Healthcare Utilisation? A Panel Study from Burkina Faso. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186543

Beaugé Y, De Allegri M, Ouédraogo S, Bonnet E, Kuunibe N, Ridde V. Do Targeted User Fee Exemptions Reach the Ultra-Poor and Increase their Healthcare Utilisation? A Panel Study from Burkina Faso. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186543

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeaugé, Yvonne, Manuela De Allegri, Samiratou Ouédraogo, Emmanuel Bonnet, Naasegnibe Kuunibe, and Valéry Ridde. 2020. "Do Targeted User Fee Exemptions Reach the Ultra-Poor and Increase their Healthcare Utilisation? A Panel Study from Burkina Faso" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18: 6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186543

APA StyleBeaugé, Y., De Allegri, M., Ouédraogo, S., Bonnet, E., Kuunibe, N., & Ridde, V. (2020). Do Targeted User Fee Exemptions Reach the Ultra-Poor and Increase their Healthcare Utilisation? A Panel Study from Burkina Faso. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186543