Outcomes of Consumer Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Aim and Design

3.2. Research Questions

- –

- What were the attributes of consumer involvement in mental health nursing education in the last 10 years?

- –

- What were the outcomes of consumer involvement in mental health nursing education for nursing students in the last 10 years?

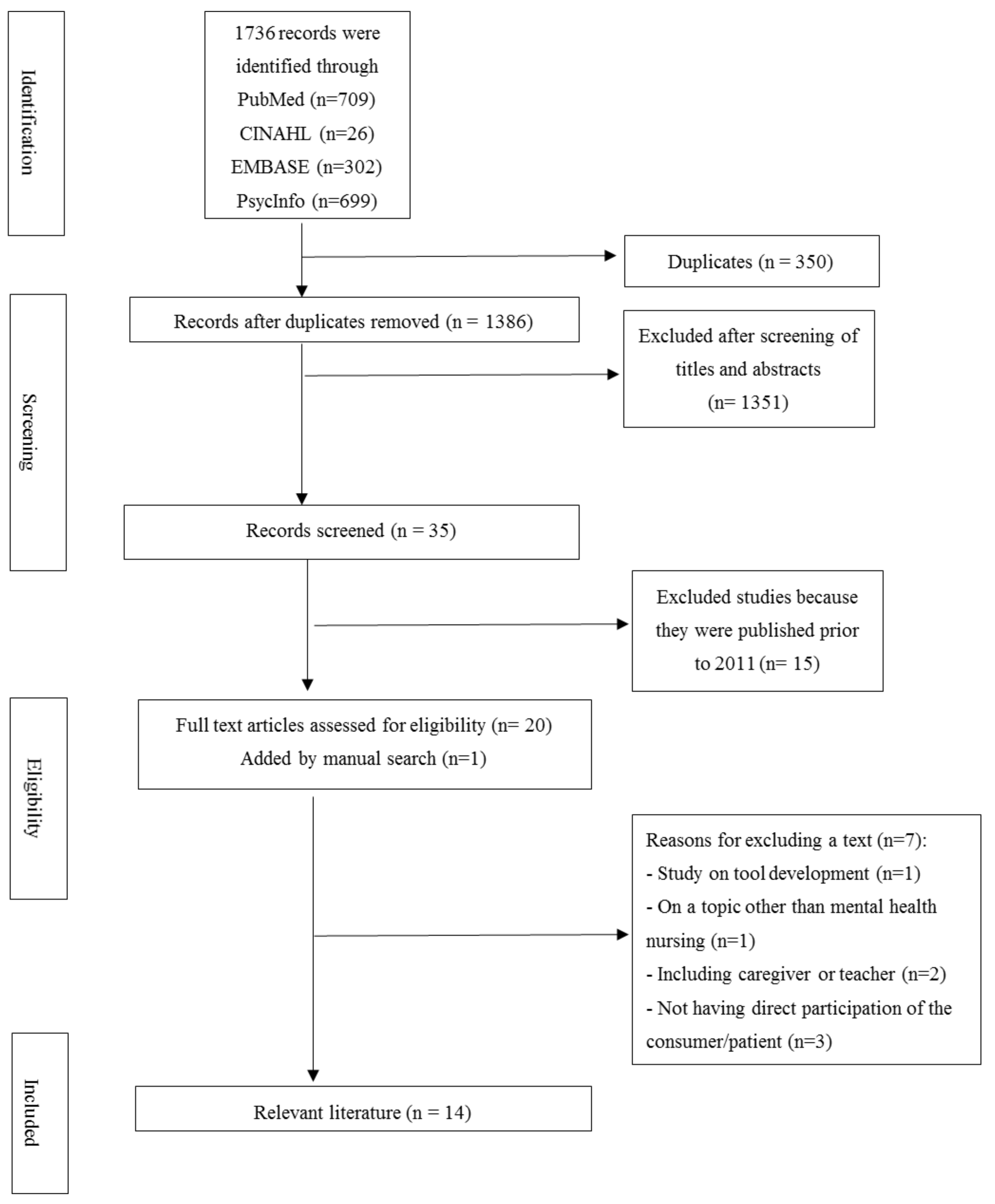

3.3. Literature Search

3.4. Quality Evaluation of Literature

3.5. Literature Analysis

4. Results

4.1. General Characteristics of the Literature

4.2. Topics of Education Using Consumer Involvement

4.3. Education Delivery for the Consumer

4.4. The Outcomes of Mental Health Nursing Education Using Consumer Involvement

| Authors (Year) | Participants | Education Subject | Consumer Involvement | Significant Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happell et al. [7] | 68 | Lived experiences of patients with a major psychotic illness (i.e., diagnosis, treatment, recovery model, nursing care, attitudes as a mental health nurse) | Two-hour lecture | Measuring the attitude of nursing students toward consumer involvement by a consumer participation questionnaire:

|

| Byrne et al. [26] | 12 | Recovery for mental health nursing practice | Lectures on lived experience, providing advice and support in a non-directive manner when discussing experiences after role play, autonomous coordination, and teaching; | Themes on experiences with consumer involvement:

|

| Byrne et al. [16] | 12 | Recovery for mental health nursing practice | Lectures on lived experiences, autonomous coordination (e.g., education delivery, assessment, evaluation), and teaching | Themes on nursing students’ views of and experiences with consumer involvement:

|

| O’Donnell and Gormley [15] | 12 (2 focus groups) | Not specified | Not specified | Student perceptions about consumer involvement:

|

| Byrne et al. [29] | 110, consumer-led course 61, nurse-led course | Recovery in mental health nursing | The lived experience-led course | Comparison of between-group differences using the “Mental Health Consumer Participation Questionnaire:”

|

| Happell et al. [31] | 131, consumer-led course 70, nurse-led course | Recovery approach to care | Autonomous coordination (e.g., coordinate the course, content, delivery) | Measuring nursing students’ attitudes toward people with mental illness:

|

| Stacey et al. [27] | 112, first-year nursing students receiving inquiry-based learning | Mental health recovery | Co-facilitator of inquiry-based learning; Utilizing elements of their personal story as triggers for learning | Themes on the lived experiences of co-facilitators:

|

| Stacey and Pearson [25] | 15, final year nursing students | Interpersonal skill assessment | Verbal (15-min) and written feedback on students’ initial interview (30-min) in a simulated scenario | Themes on the nature of learning based on the feedback given by consumers:

|

| Happell et al. [30] | 194 | Mental health recovery (COMMUNE project) | Not specified | Self-report measures: The Mental Health Nurse Education Survey (MHNES), The Health Care version of the Opening Minds Scale (OMS), The Consumer Participation Questionnaire (CPQ):

|

| Happell et al. [33] | 51 (8 focus groups) | Mental health recovery (COMMUNE project) | EBE-led teaching |

|

| Happell et al. [32] | 51 (8 focus groups) | Mental health recovery (COMMUNE project) | EBE-led teaching |

|

| Happell et al. [34] | 51 (8 focus groups) | Mental health recovery (COMMUNE project) | EBE-led teaching |

|

| Happell et al. [22] | 51 (8 focus groups) | Mental health recovery (COMMUNE project) | EBE-led teaching |

|

| Happell et al. [20] | 51 (8 focus groups) | Mental health recovery (COMMUNE project) | EBE-led teaching |

|

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Epidemiological Survey of Mental Disorders in Korea; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Korea, 2017. Available online: http://www.korea.kr/archive/expDocView.do?docId=37547 (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Alvarez, K.; Fillbrunn, M.; Green, J.G.; Jackson, J.S.; Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Sadikova, E.; Sampson, N.A.; Alegría, M. Race/ethnicity, nativity, and lifetime risk of mental disorders in US adults. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, D.A. Healthcare curriculum influences on stigma towards mental illness: Core psychiatry course impact on pharmacy, nursing and social work student attitudes. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019, 11, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.J.; Moxham, L.; Patterson, C.; Perlman, D.; Lopez, V.; Goh, Y.S. Students’ mental health clinical placements, clinical confidence and stigma surrounding mental illness: A correlational study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 84, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, H.L.; Seow, E.; Chua, B.Y.; Xie, H.; Wang, J.; Lau, Y.W.; Chong, S.A.; Subramaniam, M. Why is psychiatric nursing not the preferred option for nursing students: A cross-sectional study examining pre-nursing and nursing school factors. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 52, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, H.; O’Brien, A.J. Educational intervention to decrease stigmatizing attitudes of undergraduate nurses towards people with mental illness. Int. J. Men. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happell, B.; Moxham, L.; Platania-Phung, C. The impact of mental health nursing education on undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes to consumer participation. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 32, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.M. The pursuit of excellence and innovation in service user involvement in nurse education programmes: Report from a travel scholarship. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2013, 13, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goossen, C.; Austin, M.J. Service user involvement in UK social service agencies and social work education. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2017, 53, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gordon, S.; Ellis, P.; Gallagher, P.; Purdie, G. Service users teaching the recovery paradigm to final year medical students. A New Zealand approach. Health Issues 2014, 113, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bamgbade, B.A.; Barner, J.C.; Ford, K.H. Evaluating the impact of an anti-stigma intervention on pharmacy students’ willingness to counsel people living with mental illness. Comm. Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towle, A.; Bainbridge, L.; Godolphin, W.; Katz, A.; Kline, C.; Lown, B.; Madularu, I.; Solomon, P.; Thistlethwaite, J. Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Med. Educ. 2005, 44, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tait, L.; Lester, H. Encouraging user involvement in mental health services. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2005, 11, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Roper, C. Promoting genuine consumer participation in mental health education: A consumer academic role. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’ Donnell, H.; Gormley, K. Service user involvement in nurse education: Perceptions of mental health nursing students. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 20, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.; Happell, B.; Welch, T.; Moxham, L.J. ‘Things you can’t learn from books’: Teaching recovery from a lived experience perspective. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 22, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, S.; Risk, I.; Masters, H.; Brown, N. Mental health service user involvement in nurse education: Exploring the issues. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2000, 7, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisby, R. User involvement in mental health branch education: Client review presentations. Nurse Educ. Today 2001, 21, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, B. Mental health service user involvement in nurse education: A catalyst for transformative learning. J. Ment. Health 2008, 17, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Waks, S.; Horgan, A.; Greaney, S.; Manning, F.; Goodwin, J.; Bocking, J.; Scholz, B.; Hals, E.; Granerud, A.; et al. “It is much more real when it comes from them”: The role of experts by experience in the integration of mental health nursing theory and practice. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J. Service user involvement in pre-registration mental health nurse education classroom settings: A review of the literature. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Waks, S.; Horgan, A.; Greaney, S.; Bocking, J.; Manning, F.; Goodwin, J.; Scholz, B.; van der Vaart, K.J.; Allon, J.; et al. Expert by experience involvement in mental health nursing education: Nursing students’ perspectives on potential improvements. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 40, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrard, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method, 5th ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-128-411-519-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, G.; Pearson, M. Exploring the influence of feedback given by people with lived experience of mental distress on learning for preregistration mental health students. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 25, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.; Happell, B.; Welch, A.; Moxham, L. Reflecting on holistic nursing: The contribution of an academic with lived experience of mental health service use. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 34, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, G.; Oxley, R.; Aubeeluck, A. Combining lived experience with the facilitation of enquiry-based learning: A ‘trigger’ for transformative learning. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Co-production of Mental Health Nursing Education. Practice Guidelines for Co-Production of Mental Health Nursing Education. Available online: http://commune.hi.is/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/COMMUNE-Practice-Guidelines-2.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Byrne, L.; Platania-Phung, C.; Happell, B.; Harris, S.; Diploma Health Science; M Ment Hlth Nurs; Bradshaw, J. Changing nursing student attitudes to consumer participation in mental health services: A survey study of traditional and lived experience-led education. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 35, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Platania-Phung, C.; Scholz, B.; Bocking, J.; Horgan, A.; Manning, F.; Doody, R.; Hals, E.; Granerud, A.; Lahti, M.; et al. Changing attitudes: The impact of expert by experience involvement in mental health nursing education: An international survey study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 480–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Byrne, L.; Platania-Phung, C.; Harris, S.; Bradshaw, J.; Davies, J. Lived-experience participation in nurse education: Reducing stigma and enhancing popularity. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Waks, S.; Bocking, J.; Horgan, A.; Manning, F.; Greaney, S.; Goodwin, J.; Scholz, B.; van der Vaart, K.J.; Allon, J.; et al. ‘There’s more to a person than what’s in front of you’: Nursing students’ experiences of consumer taught mental health education. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Waks, S.; Bocking, J.; Horgan, A.; Manning, F.; Greaney, S.; Goodwin, J.; Scholz, B.; van der Vaart, J.K.; Allon, J.; et al. “I felt some prejudice in the back of my head”: Nursing students’ perspectives on learning about mental health from “Experts by Experience.”. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 26, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happell, B.; Waks, S.; Bocking, J.; Horgan, A.; Manning, F.; Greaney, S.; Goodwin, J.; Scholz, B.; van der Vaart, K.J.; Allon, J.; et al. “But I’m not going to be a mental health nurse”: Nursing students’ perceptions of the influence of experts by experience on their attitudes to mental health nursing. J. Ment. Health 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scammell, J.; Heaslip, V.; Crowley, E. Service user involvement in preregistration general nurse education: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.H. [Effects of university students’ mental health in social welfare class with people with mental illness on the change of attitude towards people with mental illness and social distance]. Korean J. Soc. Welf. Educ. 2020, 50, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, S.H.; Seo, D.M.; Cho, Y.H. Examined the meanings of disability awareness education which the people with disabilities had joined-Focused on developmental disabilities. J. Rehabil. Res. 2016, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speed, S.; Griffiths, J.; Horne, M.; Keeley, P. Pitfalls, perils and payments: Service user, careers and teaching staff perceptions of the barriers to involvement in nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrance, C.; Mansell, I.; Wilson, C. Learning objects? Nurse educators’ views on using patients for student learning: Ethics and consent. Educ. Health 2012, 25, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.M.S.; Shek, D.T.L.; Chen, J.M.T. Changes in the participants in a community-based positive youth development program in Hong Kong: Objective outcome evaluation using a one-group pretest-posttest design. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 961–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speers, J.; Lathlean, J. Service user involvement in giving mental health students feedback on placement: A participatory action research study. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e84–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, A.; Manning, F.; Bocking, J.; Happell, B.; Lahti, M.; Doody, R.; Griffin, M.; Bradley, S.K.; Russell, S.; Einar Bjornsson, E.; et al. ‘To be treated as a human’: Using co-production to explore experts by experience involvement in mental health nursing education—The COMMUNE project. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, B.; Skärsäter, I.; Doyle, L.; Ellilä, H.; Jormfeldt, H.; Lahti, M.; Higgins, A.; Meade, O.; Sitvast, J.; Stickley, T.; et al. Working with families affected by mental distress: Stakeholders’ perceptions of mental health nurses educational needs. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Bennetts, W.; Harris, S.; Platania-Phung, C.; Tohotoa, J.; Byrne, L.; Wynaden, D. Lived experience in teaching mental health nursing: Issues of fear and power. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, C.; Holt, J. Involving the public in mental health and learning disability research: Can we, should we, do we? J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgan, A.; Manning, F.; Donovan, M.O.; Doody, R.; Savage, E.; Bradley, S.K.; Dorrity, C.; O’Sullivan, H.; Goodwin, J.; Greaneyet, S.; et al. Expert by experience involvement in mental health nursing education: The co-production of standards between experts by experience and academics in mental health nursing. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happell, B.; Byrne, L.; McAllister, M.; Lampshire, D.; Roper, C.; Gaskin, C.J.; Martin, G.; Wynaden, D.; McKenna, B.; Lakeman, R.; et al. Consumer involvement in the tertiary-level education of mental health professionals: A systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Content | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | 5 | 35.7 |

| UK | 3 | 21.4 | |

| Multisite | 6 | 42.9 | |

| Published Year | 2011 | 1 | 7.1 |

| 2013 | 3 | 21.4 | |

| 2014 | 2 | 14.4 | |

| 2015 | 1 | 7.1 | |

| 2018 | 1 | 7.1 | |

| 2019 | 5 | 35.8 | |

| 2020 | 1 | 7.1 | |

| Research Design | Quantitative study | 4 | 28.6 |

| (pre–post design) | |||

| Qualitative study | 10 | 71.4 | |

| (thematic analysis, phenomenological study) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, K.I.; Joung, J. Outcomes of Consumer Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186756

Kang KI, Joung J. Outcomes of Consumer Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186756

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Kyung Im, and Jaewon Joung. 2020. "Outcomes of Consumer Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: An Integrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18: 6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186756

APA StyleKang, K. I., & Joung, J. (2020). Outcomes of Consumer Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6756. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186756